Story of fortune telling

As fortune telling , divination or divination numerous practices and methods are summarized, which are intended to predict future events or otherwise to obtain hidden knowledge that was not available to the ordinary senses.

Early days

Fortune telling is historically proven in all societies and ages from which there are any written testimonies. According to the oldest written documents found in the Middle East, it played a fundamental social role during that period. In the 3rd millennium BC, an abundance of pertinent practices is already mentioned, including lekanomancy (prophecy using oil), teratomancy (predictions based on deformities) and oniromancy (interpretation of warning dreams). The most sophisticated technique at that time was the haruspicus , the prediction based on the intestines of specially slaughtered sacrificial animals. The strictly followed procedures were so refined that one can deduce from them a history that goes back much further, and they required very precise morphological and anatomical observation.

From the beginning, knowledge of the future was ascribed only to divine beings . The gods, it was believed, sent signs, the interpretation of which allowed man to at least foresee the future. It was based on a belief in the existence of correspondences : correspondences between the macrocosm and the microcosm ( astrology ) and correspondences between the divine and the human world. The specialists in the mantic disciplines made records of observed connections between events, evaluated these and thus accumulated increasingly complex knowledge. This expresses a deterministic worldview and a fatalistic attitude. However, there could well be a belief in the effectiveness of magic ; the interpreter of signs could, thanks to his knowledge, be a magician at the same time, especially since the divinations mostly only indicated tendencies.

In Palestine , fortune telling was very widespread in the 2nd millennium BC, as demonstrated by numerous passages in the Old Testament according to modern exegesis . And that applies to the Hebrews as well as to the other peoples there. It was not until the turn of the last millennium BC that religious authors tried to exterminate or drive out fortune tellers, which, despite considerable efforts, had only moderate success.

Fortune telling was also of great importance among the Teutons and the Celts , who also used a variety of methods, including prophecy from animal voices or from the flight of birds. Among the Celts, divination specialists, the druids , had a considerable influence on politics, in which they sometimes even actively interfered.

Most archaic peoples also have a “proto- astrology ” which, in contrast to actual astrology, hardly requires any mathematical knowledge. Its expression in ancient Babylonia a good thousand years before the beginning of our era is well known. Here the heavenly vault was conceived as a concrete correspondence to the earthly world. Individual constellations were assigned to specific cities, the moving planets to specific people or states. One observed the movements of the sky lights and the changes in their luminosity and interpreted these as harbingers of important events, which mostly affected politics and the other fate of society as a whole. Associated with this was a high degree of determinism, which is expressed in formulations such as: "If the moon darkens the planet Jupiter, then a king will die this year".

Another form of prophecy, which was already known to all peoples in archaic times, is prophecy . Prophets proclaim the words of gods and are therefore not counted among the fortune tellers who interpret external signs.

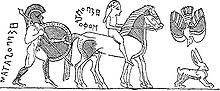

Greek antiquity

In ancient Greece , fortune telling was originally considered a gift given by the gods to chosen people . This should enable these heroes to understand the signs of the gods, but they were presented in such human terms that they often intentionally made their messages complicated and confusing. Fortune telling was later developed into a learnable science in which (as far as has been handed down) around 230 different methods were in use. "The Greeks do not neglect any means to find out about the future" (Minois). The interpretation of dreams ( oniromancy ) took a preferred place , because dreams were viewed as direct divine communications, which, however, are often allegorical and therefore require interpretation. The belief in this meaning of dreams was widespread; Even among the greatest skeptics , few doubted it. Minois describes the oniromancy experts of the time as "excellent psychologists (...) who combine prudence with knowledge of the human soul".

Another specialty of the ancient Greeks was the intuitive or inspired divination with the special form of the oracle . These are also messages from the gods, which, however - often in ecstasy - were uttered by prophets . In the case of the oracles, the divine message was initially dark and enigmatic, which is why, in addition to the numerous oracle sites themselves, there were considerably more exegetes whose task it was to decipher the meaning of the messages transmitted. The most important oracle site in Delphi , which was administered by priests of the god Apollo , existed for over a thousand years, despite the repeated criticism of the colossal enrichment of the profiting priesthood and of the unreliability, even viability of the predictions. Because of the obscurity of the wording, the non-occurrence of a prophecy could always be explained by the fact that the oracle had been interpreted badly, and that Apollo might have deliberately given wrong information for whatever reason was considered in such cases. The influence of the oracles on politics was enormous and obviously in many cases strongly determined by one's own interests. Minois even speaks of a "futurocracy", that is, rule of the (alleged) future.

As the oracle sites began to lose credibility and the general interest turned away from the prophecies of collective fates and turned towards the individual, astrology came into play: the art of predicting individual fate based on the constellation of the planets on the day of birth. The first astrology school in the Hellenistic world was founded by the Babylonian Berossos at the end of the fourth century BC on the island of Kos . His predictions soon made him very famous, and his teachings found favor with the spiritual elite, while the common people largely clung to traditional divination. Astrology met the increasing striving for rationality and intellectual rigor; it was considered a science. The masterpiece of Hellenistic astrology, the Tetrabiblos of Ptolemy (middle of the 2nd century AD), builds on his basic astronomical work Almagest , which for the author was only a necessary preliminary work for the essential goal, with the help of astrology To know the future. The underlying world view was strictly deterministic for Berossos and connected with the conviction that all events repeat themselves after 432,000 years. Ptolemy, on the other hand, and with him most of the later astrologers, represented the softened determinism of Stoic philosophy, from the point of view of which astrology even became an instrument of liberation: if I know what is likely to happen, then I can try to avoid it.

The most influential proponent of divination was Plato , who even stated which organ enables this ability, namely the liver ( Timaeus , 72). The power of vision was given to us by the gods to alleviate the inadequacy of the intellect, and it can most likely come into play when the latter is weakened or asleep. Therefore z. For example, the oracle at Delphi "insanely" gave a lot of helpful information, "but poor understanding or nothing at all" ( Phaedrus ). Plato's views, which, like Berossus, were based on an eternal return at very long intervals, were further developed by pagan philosophers until the first centuries after Christianity , such as Plotinus , Iamblichus and Porphyrios . The view of Aristotle and the Pythagoreans as well as influential poets such as Hesiod , Homer , Sophocles and Aeschylus was similar, although Aristotle, like Plato, described most seers as charlatans and only recognized true divination in particularly gifted people. For this reason, Plato demanded that the state should monopolistically control seership. Basic proponents of divination were also the Stoics .

However, this faced numerous opponents, of which the Cynics and the Skeptics were the most determined. Since they did not believe that knowing the present was possible, the claim to know the future was ridiculous madness for them, and the stupid people who could be manipulated in this way were sarcastic . So argued the skeptic Karneades in the 2nd century BC. BC, human action is not predictable, and therefore predictions in this regard could at best be true by chance. If, on the other hand, the future were necessarily predetermined, the prediction would be useless, even harmful. In particular, astrology called Karneades a deception, because Gemini have identical horoscopes and yet very different fates, while conversely, many people die at the same time in a battle, although they have very different horoscopes. The cynic Oinomaos of Gadara went even further in his polemic The Juggling of the Charlatans , where he blamed the oracle of Delphi for the deaths of countless people who had been sent to perdition with false advice through the malicious behavior of the Delphic “magicians”. Similarly, in the late 5th century BC. The historian Thucydides in The Peloponnesian War showed how divination was used in politics instead of rational arguments as a tool to manipulate the gullible public, and therefore warned in principle against falling for such fraud out of superstition. In addition to the skeptics and cynics, the Epicureans were also fundamental opponents of divination . In the comedies of the time, the seers were made fun of, with Aristophanes distinguishing himself with particularly biting caricatures, and the rhetoric manuals recommended that arguments should always be backed up with a few suitable oracles.

For the first time in Greek culture, serious thought was given to the concept and the problem of prediction, and all conceivable answers to related questions - at least Minois - were already formulated at that time. As a replacement for the increasingly dubious oracles and other prophecies, a new form of prediction appeared at the latest in the 5th century BC, the utopia .

Roman antiquity

In contrast to the Greeks, the Latins were concerned only with the present and the immediate future, and with regard to the latter they were not concerned with knowledge, but with the purely practical question of how they could ensure the good will of the gods for their projects . There were few prophets and seers among them, and very few oracles. One was not primarily interested in finding out the opinion of the gods, but rather in influencing them if necessary. Even when the gods evidently expressed their anger through drastic omens such as solar eclipses or lightning bolts from the blue, the Romans did not try to interpret them, but concentrated on finding the atonement ceremony ( procuratio ) appropriate to the situation and through this the divine one To cancel anger - a process of legal rigor and liability, also for the God involved. Therefore, fortune telling in ancient Rome traditionally had a magical character and amounted to turning off the gods and letting man alone decide his future.

After contact with the Greek oracles, however, an interest in real prophecy also spread among the Romans. The haruspices (specialists in the intestinal inspection) among the neighboring Etruscans , who had been consulted occasionally in earlier times, but generally viewed with suspicion, were of particular importance . Soon every rich and powerful Roman kept his own haruspex, although the basic magical orientation was retained. Since in Etruria itself the once highly developed art of divination fell into disrepair after its incorporation into the Roman Empire, the Haruspice was ultimately in the service of the Roman aristocracy, while the people discovered the numerous new methods of divination from the conquered territories for themselves. The Senate was troubled by this development and began towards the end of the 3rd century BC. To fight divination or to put it in his own service.

The spreading belief in fortune telling made it an extraordinary instrument of power. So it was only logical that Augustus , the founder of the Roman Empire , tried to bring it under his control and largely forbade it in the private interest. All oracle books that can be found in Rome were burned or kept for the emperor's personal use (12 AD). Due to the great popularity of the seers, however, some of them received official approval, combined with the requirements that they only work in public and no longer predict any deaths. Under Tiberius , illicit fortune-telling became a serious offense that could result in death. All astrologers were banned from Italy or executed. Emperor Claudius took another significant step in AD 47 when he combined the remaining haruspices into an official state college. These efforts to place all divination in the service of the emperor and to prevent its private practice remained a constant of imperial policy. In fact, the rise of fortune-telling in those first centuries after Christianity was unstoppable, despite all prohibitions and draconian punishments, especially since the emperors themselves attached great importance to prophecies and only wanted to ensure that only they themselves could benefit from it.

While belief in all kinds of fortune-telling spread among the common people, the philosophers and poets were rather hostile to it. The fatalistic determinism to which most of them adhered made a prediction of future events seem possible in principle, but they saw no practical use in it. Fortune-telling under strict control was seen as useful only as an instrument of politics and for manipulating the morals of the largely superstitious legionaries . The most comprehensive compilation of all points of criticism against divination was presented by Marcus Tullius Cicero in his late work De Divinatione in the middle of the last century BC , in which he listed all the arguments for divination and then refuted them. A fundamental objection raised by Cicero was that there are specialists in every area of life who know better than the seers, and that fortune tellers know nothing about the causes of events, and therefore cannot predict anything in this sense. With regard to the numerous natural phenomena that were interpreted as portents, Cicero asserted that one can only marvel at them as long as one does not know their causes. Equally ridiculous is the idea that the gods give the entrails of a sacrificial animal a certain appearance at the time of sacrifice in order to communicate something to people, or that they send us indistinct messages in dreams instead of expressing themselves clearly. In general, it is an unproven claim that there are gods who know the future and let us share in this knowledge. The predictions of the astrologers are so clearly refuted by reality on a daily basis that the trust that so many still have in them is extremely strange. And in principle divination is subject to the contradiction that one can only predict predetermined events, but that the prediction is only useful if the event is not predetermined. Therefore, "ignorance of future calamities is certainly of greater use than corresponding knowledge." Cicero came to the irrevocable conclusion that divination is nothing but fraud and superstition.

With the conversion of the first emperors to Christianity , Christian prophecy , direct inspiration from the one God, remained as the only legitimate view of the future; everything else was now condemned as superstition and fraud. Since, from this point of view, the purely earthly future no longer had any meaning and this world would no longer exist for long anyway, the focus of the announcements of political and military events shifted to such global, even cosmic dimensions: the Antichrist , the return of Christ and the end the world . Against this background, the struggle against “secular” fortune-telling (in the effectiveness of which the first Christian emperors still believed) took on a new dimension: it was now one of the remnants of pagan superstition that had to be eradicated. The oracle sites were destroyed, books with pagan prophecies were burned, the Haruspice was punished with torture and death. The old gods should be silenced. And the church finally took the place of the emperor, who had previously claimed control over prophecy for himself.

On closer inspection, the confrontation of the church fathers with pagan fortune-telling was complex and not free from contradictions. The main difficulties were that they ascribed to God a knowledge of the future, but at the same time rejected the traditional belief in fate, and that they based their own faith on prophecy, but at the same time rejected any pagan prediction. Justin solved the first of these two problems in the 2nd century by introducing the distinction between foreknowledge and doom . Although God knows the future and proclaims it through the prophets, these proclamations are designed to call people to their senses and not to subject them to an unchangeable fate. Regarding the second problem, Gregory of Nyssa introduced the decisive argument in the 4th century that pagan seers and astrologers are not only charlatans and deceivers, but are sometimes also inspired by the devil and can then make accurate predictions, which however bring people to their ruin led. For this reason, astrology in particular was condemned, for it revealed the future, which only God was entitled to know.

middle Ages

As a prophetic religion that heralded an imminent end to the world, Christianity sparked an increased interest in the hereafter and in the future, and therefore the demand for seers, astrologers, fortune tellers and prophets increased regardless of the prohibitions. In the Merovingian era, as Gregor von Tours described in his Frankish History at the end of the 6th century, prophecies were omnipresent, and nothing important was undertaken without first finding out about the outcome. The holy texts were used as well as the services of witches , and even the bishops (like Gregory) believed most of these predictions, although on the other hand they complained about the numerous "false prophets", some of whom even identified themselves as Christ or called the Holy Spirit . A method that was also common within the clergy was the accidental opening of books ( Bible stabbing ), combined with the ritual invocation of God. Great importance was attached to numerous omens and dreams, and as a rule they heralded catastrophes and caused fear and sometimes even panic. The focus was on worldly matters, while the prophecy of the Antichrist, for example, seemed to have received little attention. The penalties provided for false prophets were severe, but the line between divine and diabolical prophecy was "extremely fluid" (Minois), and in practice the suppression appeared to be rather cautious.

The early Middle Ages practiced as Minois writes, "a spontaneous syncretism of the various prophetic traditions. All predictions that are useful in any way are used completely uncritically, others are invented and accepted. Having opened the gates of the future by the Christian authorities, admitting the principle of possible knowledge of the future through the mediation of the Holy Spirit or Satan, the mass of reassuring certainty believers are ready to accept any announcement that allows To cling to a fixed point in the future. ”Most of the predictions came from the bosom of the clergy themselves. On the other hand, other, non-prophetic divination practices, i.e. divination in the narrower sense of the word, as well as astrology, were rejected.

Only in the 11th and 12th centuries did a change take place. After centuries of relative intellectual stagnation, there was a spectacular spiritual renewal, including a. promoted by the rediscovery of ancient philosophical writings that had been preserved in the Arab culture. At the same time the authority of the Roman pontificate was consolidated , which now had the power and the intellectual tools to better control access to the future and to regulate the ways in which it was announced. In addition, there was the increasing threat to the existing feudal and theocratic order from newly emerging socioreligious heresies , which often referred to prophecies. In this situation, Christianity transformed from a previously prophetic religion into an institutional one that tried to monopolize access to the future. Free prophethood was now under suspicion of turmoil, and prediction had become a matter of general dispute. Faced with the threat to their authority from uncontrolled prophets like Joachim von Fiore , who even foretold the downfall of the Church, the Church eventually claimed the sole right to distinguish divinely inspired true prophets from the devil's henchmen and charlatans. The number of recognized prophets was greatly reduced, and the subject of prophecies was largely confined to the Last Judgment and its surroundings.

The numerous translations of ancient scriptures also rekindled interest in astrology, which therefore experienced a renaissance in the 12th and 13th centuries. In their wake, other pagan divination practices such as the oracle of the lotus and geomancy reappeared. From the point of view of theologians, however, it was mostly superstition and the work of the devil. In the case of astrology, however, the 13th century scholastics made a distinction between "natural" astrology, which dealt with the widely recognized influence of stars on tides, weather, earthquakes, diseases and other physical and chemical processes, and the "Superstitious" astrology, which also made statements about people's actions. The former was approved by well-known theologians such as Robert Grosseteste , Bishop of Lincoln, in its application in alchemy , medicine and meteorology , while the latter was viewed as problematic or inadmissible because it runs counter to the free will of mankind wanted by God. However, one of the most important scholastics, the Dominican Albertus Magnus , was also extremely positive about astrology related to humans, which he justified with the fact that the human soul was not originally subject to the influence of the stars, but fell into them as soon as they were "Inclinations of the flesh," as most people do. Given this, he described it as unreasonable and detrimental to freedom not to consult an astrologer before important undertakings. Similar was the view of the Franciscan Roger Bacon , the most resolute proponent of astrology within Christianity, who even recommended it to the Pope as a valuable means of converting the unbelievers. With Bacon, the contradicting attitude of the church became particularly clear: his main work Opus maius , in which he extolled astrology alongside many very modern ideas, was commissioned by Pope Clement IV ; Years later he was convicted and imprisoned for his teachings by Étienne Tempier , Bishop of Paris and the fiercest opponent of astrology at the time. On the whole, the negative attitude of the scholastics towards the practices of astrologers and other visionaries showed little effect. Posthumously they all found themselves in Hell in Dante's Divine Comedy , but during their lifetime they mostly enjoyed great popularity.

For the 14th and 15th centuries, a time of catastrophes and upheavals, Minois notes inflation and the trivialization of predictions. In the place of the rationalism of scholasticism , there was a nominalistic separation of faith and reason, combined with a disdain for the latter and a preference for the irrational and the occult. Most of the predictions, whether prophetic-inspired or astrological- "scientific" kind, concerned catastrophes up to the near end of the world, whereby it was quite common to invent and backdate the prediction only after the relevant event. The widespread willingness to believe even the most contradicting predictions was, on the other hand, the custom of using manipulated prophecies for political purposes. In the meantime, the interpretation of the flight of birds as a sign of diseases, crops and weather, commuting and palm reading were common among the people.

Modern times

Renaissance period

In view of the abuses and the associated danger of social upheaval, a certain skepticism towards inspired prophecy spread among the intellectual elite from the 15th century, and hopes were raised in astrology, which is regarded as safer and more scientific. She soon became an "indispensable advisor for the wealthy" (Minois), while simpler forms of fortune-telling enjoyed increasing popularity among the common people. Popular fortune-telling practices were extremely numerous in the early modern period and ranged from palm reading to the numerological interpretation of the date of birth and name, card reading and dice-throwing, right through to piercing the Bible. The belief in the importance of warning dreams and external signs such as earthquakes and comets was widespread, even among educated people, and the latter were particularly feared. Many manuals were in circulation for teaching the mantic arts.

Because of the associated dangers for dogmas , morality and the social order, more and more bans were issued; However, since kings and popes also used prophecies for their purposes, the prohibitions had little effect. In the middle of the 16th century, astrology became widely accepted in the intellectual and political elite as a replacement for religious prophecy, and in the period that followed it became popular among the people. The printed almanacs , which for one year in addition to astronomical events such as eclipses and conjunctions, also listed astrological predictions of all kinds, played an important role. The more prophetic predictions of Nostradamus , Paracelsus and others also received a lot of attention. In contrast, only a few, such as Michel de Montaigne , expressed fundamental doubts about the possibility of knowing the future .

17th century

It was not until the 17th century that modern science began to pose a threat to the mantic disciplines. Francis Bacon fundamentally opposed prophecy and divination based on correspondence. However, he considered astrology to be partly justified and reformable. Although he ruled out that it could make statements about human individuals, he considered astrological predictions possible with regard to the weather, the occurrence of epidemics, wars, etc. The astronomers Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei even practiced astrology themselves, Robert Boyle tried to explain the influence of the stars on humans in his optics , and Isaac Newton was also open to astrology for a long time. The attitude of the intellectual elite towards this time-honored science remained cautious and ambivalent until the end of the century, and resolute opponents such as Pierre Gassendi were the exception.

As Minois writes, “all classes of society [...] were still eager to know the future. More than ever, the people are turning to fortune tellers, who in the first half of the century provide artists with one of their favorite subjects. Countless painters and engravers have depicted the scene: Georges de la Tour , Caravaggio [...] and many others. These pictures usually show a gypsy or "Egyptian" interpreting the lines of the hand or using a coin placed on the palm of the hand. The scene provides an opportunity to shed light on the vanity and gullibility of those seeking advice, mostly young men and women dressed in precious clothes; the fortune teller's extras take advantage of the distraction to empty their pockets. ”With somewhat more sophisticated concerns, an astrologer was turned to, of which there were around 400 in Paris alone in the middle of the century, that is, one for every 100 inhabitants.

In the still popular almanacs, however, a clear decline and a thematic shift can be recorded from the middle of the 17th century, which, according to Minois, “undoubtedly” was due to the massive and persistent campaign by the churches against astrological predictions and the increasing number of prohibitions the judicial, d. H. policy-related predictions. In contrast to their still sensation-seeking titles, the statements in the almanacs became more cautious, in fact in many cases downright banal, and as a precaution they were declared as a mere pastime. The proportion of astrological predictions in these yearbooks fell considerably, that of judicial astrology even dramatically.

The prohibition and prosecution of any judicial divination in the course of the restoration of the monarchy in England from 1660 onwards was particularly rigorous. Newly published almanacs and other books were strictly censored in this regard, and renowned astrologers such as William Lilly were imprisoned for violations. Astrology had fallen into serious disrepute simply because of the role its leading representatives had played in the previous parliamentary Commonwealth . Added to this, however, was a tendency towards skepticism and rationalism that was spreading among the intellectual elite , with John Flamsteed and Jonathan Swift particularly prominent as critics and scoffers of astrology. While in the 16th century opponents of astrology were rare exceptions at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge, it was soon made clear in the Royal Society , founded in 1662 , that astrology was no longer part of the sciences. Science, church and politics were now united in their rejection.

enlightenment

In the following decades, the enlightened and skeptical attitude also gained weight on the continent, especially in France, where Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle , Molière and Jean de La Fontaine were among the critics and scoffers, and divination was in the 18th century Basically just a matter of the common people who continued to buy the almanacs en masse and consulted astrologers and fortune tellers, while these things were at best for amusement for the educated. However, with the growing importance of the poorly educated middle class in the course of the democratization that began with the French Revolution , the importance of popular divination also increased, which therefore experienced a heyday in the 19th century. The general liberalization and the dwindling influence of the churches also contributed to this, while, detached from the religious denominations, a tendency towards the spiritual spread again, which now leaned more towards the occult. In enlightened and skeptical circles, the practices of fortune tellers and the superstitions of their customers were despised and mocked, but at the same time classified as harmless. Fortune-telling, which had previously been at home in marginalized social groups such as the gypsies, now acquired the status of a recognized profession, whose customers came mainly from the milieu of civil servants, merchants and employees, but also included noble circles up to the nobility, although the latter mostly had such services only secretly claimed, because otherwise they would have exposed themselves to ridicule. This profession was practiced mainly by single women, for whom it was one of the few opportunities to gain respect and wealth independently, and the clientele was predominantly female. Card reading established itself as the most popular form of divination during this period. Around 1850 the crystal ball was added as a new utensil , and prediction by means of magnetic somnambulism came into fashion, which was soon followed by spiritualism .

20th century

Despite the spectacular development and popularization of the exact sciences, the popularity of popular divination did not decrease in the 20th century either. Among the approximately 25 methods in use, astrology in particular experienced a renewed boom. At the beginning of the century, newspaper astrology appeared in the USA, only to establish itself in Europe between the world wars. Parapsychological precognition research was also added , also starting from the USA, where the first such experiments were carried out at Duke University in 1933 . As in previous centuries, the advance of science with a simultaneous decline in the importance of the churches did not lead to a decline in belief in the irrational, but to its reorientation in the direction of esotericism and parapsychology . And not only the common people listened to the fortune tellers and clairvoyants, but also, in secret, politicians of the highest rank. Joseph Stalin regularly consulted a Georgian clairvoyant and a Polish astrologer, and the presidents of the United States traditionally have occult advisers such as the astrologer Jeane Dixon , whose services Franklin D. Roosevelt regularly used. During World War II , both German and Allied propaganda used astrological predictions as a psychological weapon. Minois prophesies “a bright future for sure” to popular divination.

literature

- Gerhard Eis : Fortune telling texts of the late Middle Ages: From manuscripts and incunabula. Berlin / Bielefeld / Munich 1956 (= texts of the late Middle Ages , 1).

- Wolfram Hogrebe (Ed.): Mantik. Profiles of prognostic knowledge in science and culture. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2005, ISBN 3-8260-3262-4 ( preview on Google Books )

- Georges Minois : History of the Future. Oracle, prophecies, utopias, forecasts. Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf / Zurich 1998, ISBN 3-538-07072-5 . (New edition in 2002 under the title The History of Prophecies )

- Markus Mueller: Controlled time: Life orientation and shaping the future through calendar forecasting between antiquity and modern times. (= Publications of the University Library Kassel. 8). Kassel 2010.

- Yves de Sike: Histoire de la Divination. Larousse, 2001.

- Christa Agnes Tuczay : Cultural History of Medieval Fortune Telling . DeGruyter, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-11-024040-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Georges Minois : Histoire de l'Avenir. Paris 1996; German: history of the future. Düsseldorf / Zurich 1998, p. 26f; see also Georges Contenau : La Divination chez les Assyriens et les Babyloniens. Paris 1940, and W. Farber: Witchcraft, magic, and divination in ancient Mesopotamia. In: Jack M. Sasson (Ed.): Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Volume 3, New York 1995, pp. 1895-1909.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 27-29.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 29f; see also O. Eissfeldt: Divination in the Old Testament. In: F. Wendel: La divination en Mésopotamie ancienne et dans les régions voisines. XIVe Rencontre assyriologique internationale. Strasbourg 1965, pp. 141-146, and Jean Michel de Tarragon: Witchcraft, magic, and divination in Canaan and Ancient Israel. In: Jack M. Sasson (Ed.): Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Volume 3, New York 1995, pp. 2071-2081.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 58-61.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 31-33.

- ↑ Minois, p. 34.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 71-73; see also Raymond Bloch on this and the following: Les Prodiges dans l'Antiquité Classique: Grèce, Etrurie et Rome. Paris 1963.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 74-82.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 78-82 and 85-95.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 95 f. and 100-103.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 97-99.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 111-114.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 115-119.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 115 and 119-127.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 125-148; see also Marie Theres Fögen : The expropriation of fortune tellers. Studies on the imperial monopoly of knowledge in late antiquity. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1993. (Paperback edition 1997)

- ↑ Minois, pp. 148-160; Cicero: De Divinatione - About divination. 1991.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 142f and 160-165.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 184-193 and 199-205.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 213-221.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 224-228.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 231f and 253-268

- ↑ Minois, pp. 242-247 and 279-290; on the situation of astrology in the early Middle Ages cf. Minois, pp. 225-229.

- ↑ Minois, pp. 291-294, 302-304 and 319-339.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 342 and 380-383; see also Keith Thomas: Religion and the Decline of Magic. 1991, pp. 252f, and J. Ponthieux: Prédictions et almanachs du XVIe siècle. Dissertation. Paris I, 1973.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 342f, 383-390 and 403-430.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 438-444.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, p. 468-

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 468-471. Minois adds that there is still one astrologer for every 400 inhabitants in the Paris region.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 471-474.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 485-489.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 495-513, 575-577, 590-596 and 602-605.

- ↑ Minois: History of the Future. 1998, pp. 712-716, 722 and 724-727; see also E. Howe: Astrology and Psychological Warfare during World War II . London 1967.