Nostradamus

Nostradamus , Latinized for Michel de Nostredame , (born December 14, 1503 in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence , Provence , † July 2, 1566 in Salon-de-Provence ) was a French pharmacist and worked as a doctor and astrologer . During his lifetime made him his prophetic poems famous, consisting of groups of 100 combined quatrains (quatrains) passed the so-called centuries .

Life

family

His parents were Jaume de Nostredame, grain merchant, ecclesiastical notary in Saint-Rémy since at least 1501 and mayor since 1513, and Reyniere (Renée) de Saint-Rémy. Michel was the eldest son of the couple's at least eight children. Verified siblings are Delphine, Jehan, Pierre, Hector, Louis, Bertrand, Jean II and Antoine.

According to the family legend, which was mainly rumored by Nostradamus' son César and his follower, secretary and biographer Jean-Aimé de Chavigny , the great-grandfathers Jean de Saint-Rémy († before 1504 or 1518) and Pierre de Nostredame († before 1503) were the king's personal physicians René of Naples , Sicily and Jerusalem , Duke of Lorraine and Count of Provence (1409–1480) who entered the Provencal folk legends as "le bon roi René" or his eldest son Johann , Duke of Lorraine and Calabria ( 1425-1470). In fact, Pierre de Nostredame was a grain merchant and notary, Jean de Saint-Rémy a medic, city treasurer and tax collector.

The paternal family, who came from regional Judaism , had apparently converted to the Catholic faith with grandfather Pierre (who was originally called Guy Gassonet) . At the time of baptism, he took on the name Nostredame - probably after the church in which he was baptized or after the day of Saints on which it happened.

childhood and education

He is said to have spent his early childhood in the care of his great-grandfather Jean de Saint-Rémy, not with his grandfather, who was called René and had already passed away. The great-grandfather allegedly taught him Latin , Greek , Hebrew , Kabbalah , mathematics and astrology , but after 1504 there are no sources of any information about the life and activities of the great-grandfather. In 1518 at the latest, after the unproven death of his great-grandfather who is said to have bequeathed his astrolabe to him, Michel was sent to the University of Avignon . About a year later he had to give up his studies (the so-called trivium , i.e. grammar , rhetoric , logic ) because the plague had broken out, and he became a pharmacist .

In 1529 he studied at least for a short time in Montpellier , where he is said to have been "very rebellious". It has not been proven whether he also studied elsewhere and actually obtained a doctorate in medicine. All that is known is that he resumed his wandering life.

Wandering years

In 1533 he received a letter from the eminent humanist Julius Caesar Scaliger , who finally invited him to work with him in Agen . He settled in nearby Port-Sainte-Marie, where he stayed for the next four years. He married a lady whose name is given as Henriette d'Encausse, with whom he had a son and a daughter within a short time. Nostradamus lost his family in 1535 due to an unknown infectious disease ( plague or perhaps diphtheria, which appeared for the first time ).

This loss of family, combined with disputes between him and his wife's parents about the return of the dowry , a dispute with Scaliger and a summons from the Inquisition to Toulouse were reason enough for him to travel again. He is said to have attracted the attention of the Inquisition with a remark to an ore caster. When he was involved in the production of a statue of the Madonna , Nostradamus is said to have accused him of making "devil pictures". Defenders of Nostradamus' orthodoxy later tried to turn this sentence to refer to the aesthetic quality of the work. It should be noted that some Protestants at that time were radically iconoclastic and any criticism of representational works of art could therefore be regarded as an expression of sympathy with them. Nostradamus is said to have been a devout Catholic and never missed an opportunity to affirm his orthodoxy in writing, but at least a letter from him dated July 15, 1561 to the Protestant amateur astronomer and Lutheran Lorenz Tubbe (Laurentius Tubbius Pomeranus) has come down to the possibilities of interpretation leaves open: Here in Salon, as elsewhere, hatred and quarreling among the respected gentlemen are simmering because of the faith; Anger grows among the defenders of the papist tradition - as well as among those who profess the doctrine of primordial piety. A certain Franciscan who is very tongue-tied in the pulpit turns the crowd against the Lutherans, incites them to violence and even urges them to commit murder. It almost came on Good Friday. 500 men armed with iron bars invaded the church like madmen. Nostradamus was called a Lutheran. Almost all of the other suspects have fled. As for me, terrified by this violent anger, I fled to Avignon.

Over the next five years he is said to have traveled through Alsace , Lorraine and Italy and returned to Provence in 1541. However, his stays cannot be documented. In 1544 he fought an outbreak of the plague in Marseille together with the doctor Louis Serre , from the end of May 1546 he worked alone in Aix , Salon and in 1547 briefly also (whether for the treatment of the plague or for other reasons is unknown) in Lyon .

Sedentariness

His father died in 1547, and on November 26th of the same year he was a second marriage to the Salonian widow Anne Ponsarde. Since his wife was wealthy, he was able to devote himself mainly to his literary work in the following years. This marriage resulted in three sons and three daughters (Madeleine, César, Charles, André, Anne and, as the last-born, Diane).

He seems to have participated in economic ventures and speculations with considerable success. In particular, his later involvement in the construction of the canal between Rhone and Durance by Adam de Craponne can be proven . So Nostradamus was a wealthy man for the time.

He owed his almanacs to a meeting with the French King Henry II and his wife Caterina de 'Medici in 1555. The stay at court did not seem to be very successful at first, because the king was not particularly interested in prophecies. Nostradamus was plagued by money problems, which forced him to take a loan from the famous scholar Jean Morel. In addition, there was a first attack of gout during this time , which became a chronic ailment in the following years.

The Queen, however, who was far more interested in the occult than her husband, and in Nostradamus in particular, invited him to create horoscopes for her children. In 1564 - two years before his death - the now 60-year-old and wealthy Nostradamus is said to be on the occasion of a visit by the new King Charles IX. and his mother Catherine were appointed personal physician to the king in Salon .

On the night of July 1 to July 2, 1566, Nostradamus died at the age of 62 of a heart attack or an asthma attack as a result of his dropsy , which he himself is said to have prophesied. He had suffered from chronic gout for years , which led to kidney failure, and was buried in the Saint-François-de-Salon Minorite Church. In the turmoil of the French Revolution , his grave was desecrated by National Guards from Marseille in 1791 and the bones were scattered. On this occasion, one of the soldiers is said to have used Nostradamus' skull as a drinking bowl. Finally, the remains of the bones were reburied in the side chapel of the Virgin Mary in the Dominican church of Saint-Laurent-de-Salon.

His wife Anne survived him by 18 years, she died in 1584. The family track is lost in the 17th century .

Nostradamus as a doctor

It is unclear whether Nostradamus completed his medical degree. According to a document from Guillaume Rondelet, the then “student procurator” and later chancellor of the University of Montpellier, Nostradamus was denied further studies because he was considered a pharmacist and pharmacists were not allowed to study medicine.

The following can be said:

- There is no evidence that Nostradamus ever called himself a "doctor".

- That he was a pharmacist, or more precisely: a producer of pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and jams, is proven by his own relevant writings.

- In 1554 the city of Aix-en-Provence appointed him "master" instead of "doctor".

- In 1555 he told a gathering of doctors in Lyon that he was not a doctor himself.

- Some of his correspondents and editors have called him a "doctor" and some have not.

- Whether he was actually appointed royal doctor and private councilor in 1564 is open to doubts, since the report, written in 1614, 50 years later, comes from Nostradamus' son Cesar, and which Leroy and Brind'Amour say about his father and his influence at the royal court and therefore do not consider it credible.

Nostradamus as an astrologer

On the question of whether Nostradamus was a real, professional astrologer, it can be noted:

- There is no evidence that Nostradamus ever called himself an "astrologer", rather he always called himself astrophile ("star friend").

- Creating a horoscope as part of therapy was common at the time.

- Because of the plague he had to leave the University of Avignon in 1520, too early to have studied astrology there as part of the "Quadrivium" (second part of the course).

- Since he soon had to leave the University of Montpellier in 1529, he cannot have studied astrology there either.

- In 1557 in his Quatrain VI.100 he attacked the astrologers and even dedicated them to hell.

- He has often worked as a psycho-astrological advisor but never claimed to be an astrologer. Mostly he seems to have induced his customers to purchase a horoscope from professional astrologers.

- If he had to create a horoscope himself, he usually made numerous serious mistakes (planets in the wrong signs, etc.).

- In particular, he failed to adapt the planetary positions taken from the ephemeris for the time and place of the horoscope, so he always based the horoscope on the positions for noon at the place of the ephemeris, which has massive effects on the ascendant and thus on the houses of the planets.

- His famous horoscope for Crown Prince Rudolf von Habsburg from 1565 was almost completely wrong.

- In an open letter from the astrologer Laurens Videl, who taught astrology in Avignon, he wrote: “I can say with complete certainty that you know less than nothing about real astrology ... You who do not know how to calculate the slightest movement of any star: and in no way do you understand more than the movements of how your ephemeris are to be used. "

The prophecies

Three years after his second marriage, in 1550, Nostradamus began composing annual almanacs in which the first prophecies for the respective year were printed. These brochures were published with prophecies in prose and in French instead of the traditional Latin. Nostradamus held on to the publication of these almanacs, which made him famous for the first time, until the year of his death. Since 1555 they also contained quatrains . In the same year he published a larger number of prophecies in quatrains than Les Propheties de M. Michel Nostradamus in Lyon , consisting of four "Centurien", which in turn were composed of three times a hundred and once 53 quatrains called quatrains .

Typical features of his prophecies are the almost complete lack of concrete dates and names and a very metaphorical language that probably got by without punctuation in the manuscript, which makes the prophecies puzzling up to our time and always allows new interpretations. Many of the verses contain references to astrological constellations . It was also found that many of the prophecies are paraphrases of historical texts, for example from De honesta disciplina des Petrus Crinitus, the Liber prodigiorum des Iulius Obsequens , or the Mirabilis Liber of 1523, a commentary on the Bible.

In the foreword to his son César, Nostradamus speaks a little more clearly about his prophecies and explains that these extended “from today to the year 3797”, but without going into their content. As I said, the year is rather unusual. However, if one subtracts the year of publication 1555, then one comes to a validity period of 2242 years. Five years earlier, his greatest astrological source, Richard Roussat's Livre de l'etat et mutations des temps , had published the year 2242 as the possible date for the end of the world. By the time he died, Nostradamus published seven centuries - three others are stated without evidence that they had already appeared in his lifetime in 1558. In addition, other texts are said to have been in his estate, some of which were written in prose, some as six-liner. The prose texts (if not the almanacs themselves) have been lost, the six-liner are traded as 11th and 12th centuries, although they are nowhere near 200 stanzas. A fact that was also unpleasant for Nostradamus was that shortly after the appearance of his prophecies, not only diatribes were circulating against him, but also forgeries in order to benefit from his success.

It was not until 1614 that his son César first linked stanza 35 of the first centurie of 1555 with the death of King Henry II (Nostradamus himself supposedly never heard of the idea, but rather took the stanza for this historical event in a letter from 1562 to Jean de Vauzelles III.55 in claim). The spectacular interpretation of this stanza is often wrongly given as the reason for the Prophet's fame:

- "Le lyon ieune le vieux surmontera,

- En champ bellique par singular duels:

- In the cage d'or les yeux luy creuera,

- Deux classes une, puis mourir, mort cruelle. "

- "The young lion will defeat the old one,

- On the battlefield in a single duel:

- In the golden cage he will poke out his eyes,

- Two fleets [or: armies] unite, then he will die a cruel death. "

On June 30, 1559, at the celebration of the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis , Henry II (* 1519) fought a tournament duel with blunt weapons on the Rue Saint-Antoine in Paris with Count Montgomery (* around 1530), captain of the Scottish Guard ; whose lance broke. A splinter penetrated through the visor of the helmet over the king's right eye. Heinrich II died ten days later, on July 10th, of meningitis.

Although this quatrain is often cited when giving an example of Nostradamus' successful prophecy, it is by no means precisely related to the death of Henry II. There is no evidence that Heinrich wore a golden helmet. The designation of the opponent as a young or old lion is also unclear: It has been interpreted in terms of the tournament emblems, but the heraldic use of a lion is not documented by Heinrich or Montgomery (the emblem of the Valois kings is also the rooster). The splinter of the lance did not penetrate into the eye, but over it, the eye itself remained unharmed. It was also just a wound, although some reports speak of an additional injury to the neck. If classes are derived from the Latin classis (fleet) as an alternative to the Greek klasis , the meaning does not become any clearer. Finally, a tournament match can only be viewed as a duel on the battlefield when broadcast.

Effect and reception

Famous during his lifetime thanks to his almanacs, Nostradamus is still one of the most famous writers of prophecies to this day. Nostradamus has been widely used as a protagonist in films and novels, and his prophecies - or imitations attributed to him - are repeatedly repositioned in book form. Many people consider the prophecies of Nostradamus to be the ultimate revelation of the future, and as a result of the multiple interpretations of his quatrains, it is possible to find almost any correspondence between predictions and actual events. The philosopher Max Dessoir put it: "The miracle in Nostradamus is not his text, but the art of interpreting the person who explains it". Particularly in times of war or economic instability, his prophecies are given and assigned a particularly high degree of importance.

Movies

- More About Nostradamus (1940), American short film with John Burton and Hans Conried

- World catastrophe in 1999? - The Prophecy of Nostradamus (1974), Japanese end-time disaster film from Toho Studios

- The Man Who Saw Tomorrow (1981), American documentary with Orson Welles

- Nostradamus (1994), British-German film biography with Tchéky Karyo , F. Murray Abraham , Rutger Hauer , Amanda Plummer and Julia Ormond

- Nostradamus - The Third Millennium (2003), German documentary (Director: Klaus Kamphausen; Production: Complete Media; 88 minutes)

- Nostradamus: 2012 (2009), speculative American documentary (Director: Andy Pickard; 120 minutes)

TV Shows

- First Wave - The Prophecy (1999-2001) by Francis Ford Coppola

- Switch Reloaded (2007–2012) with Bernhard Hoëcker , whoparodiesNostradamus in a fictional program “Nostradamus-TV” (an allusion to the German news channel n-tv )

- Reign (2013–2017) with Nostradamus as advisor to the French queen

music

- Roger Boggasch , Johannes Reitmeier : Nostradamus , Musical (world premiere in 2000 in Passau )

- The Bollock Brothers : The Prophecies of Nostradamus , concept album (1987)

- Christian Death : Prophecies (1996)

- Dark Angel : Black Prophecies on the album Darkness Descends (1986)

- Gerhard Grün: Nostradamus - le mystique , musical (world premiere 2003 in Bendorf )

- Haggard : And Thou Shalt Trust… The Seer , concept album on Nostradamus (1997)

- Haggard: Awaking the Centuries , concept album on Nostradamus (2000)

- Helloween : The Time of the Oath , concept album about prophecies of Nostradamus (1996)

- Justin Hayward : Nostradamus on the Songwriter album (1977)

- Japanese Combat Radio Play : Nostradamus in Real Time (2001)

- Judas Priest : Nostradamus , concept album (June 2008)

- Nikolo Kotzev: Nostradamus , rock opera (2001)

- Manfred Mann's Earth Band : Somewhere in Africa: Eyes of Nostradamus (1982)

- Saurom Lamderth : Nostradamus on the album Legado de juglares (2005)

- Al Stewart : Nostradamus on the album Past, Present and Future (1974)

- Otto M. Schwarz : Nostradamus, concert piece for wind orchestra (2002)

comics

- Ray O. Nolan (scenario), Jörg Hartmann (drawing & colors): Nostradamus, Wanderer Between Times (Ehapa Comic Collection). Egmont, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-7704-3171-7 .

- Massimo Marconi (text), Massimo De Vita (drawings): Topolino e il ritorno al passato (German knowledge is power ), 1987 (LTB 134) with Micky and Goofy

- Don Rosa (text and drawings): The Curse of Nostrildamus (Eng. The Curse of Nostrildamus ), 1989 et al. Mickey Mouse 1990-10, Hall of Fame 6: Don Rosa 2, The Greatest Stories of Donald Duck (special issue) 278, with Donald Duck and Uncle Dagobert

Works

- 1551–1555 (?), Orus Apollo, fils de Osiris, roi de Ægipte niliaque, des notes hieroglyphiques, livres deux mis en rithme par epigrammes, œuvre de incredible et admirable erudition et antiquité , manuscript, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, BN fonds français 2-594. It is a work attributed to Horapollon , an Egyptian of the 5th century , on the hieroglyphs , which are interpreted purely figuratively and allegorically (and thus incorrectly). Probably a pseudepigraphy from the 14th century . The script was translated from Greek into Latin by Jean Mercier in 1551. Nostradamus made his translation into French before 1555. Edition: Interprétation des hiéroglyphes de Horapollo. Texts inédit établi et commenté by Pierre Rollet. Ruiromer, Barcelona 1968

- 1550–1567, annual almanacs, are the editions of

- 1553, printed by Bertot in Lyon

- 1563, printed by Pierre Roux, Avignon; it is located in the Bibliothèque Arbaud, Aix-en-Provence

- and many others recently discovered and preserved or copied in the Lyons City Library (Fonds Chomarat).

- 1552, Traicté des Fardements et des Senteurs , Lyon, German 1572

- 1552, Le vray et parfaict embellisement de la face , Lyon. Translated into German by Jeremias Martius (Hieremias Martius) under the title * " Michaelis Nostradami, ... two books, in which a truthful, thorough, and popular report is given, how one first of all adorns a shapeless body, on the outside of women and men, beautiful, and make it young, and all kinds of scented, delicious, crispy water ... artificially and how to put all the fruit on the most artificial, and loveliest, in sugar and keep it for emergency use "( Jeremias Martius : Augsburg, 1572. Digitized by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek )

- 1554, A Terrifying and Wonderful Zeychen. Transferred from French by M. Joachim Heller . Single-sheet print of a comet observed by Nostradamus over Salon. First known translation into German.

- 1555, Excellent et moult utile Opuscule à touts necessaire qui desirent auoir cognoissance de plusieurs exquises Receptes , Lyon. Reprint of the two writings from 1552, supplemented by recipes for a love potion, plague pastilles and some travel memories.

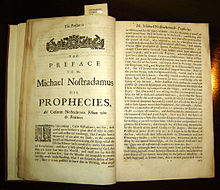

- 1555, Les Propheties de M. Michel Nostradamus , Lyon, near Macé Bonhomme, with the preface to the son César (dated March 1, 1555), the Centuries 1-3 and the Quatrains 1-53 of the 4th Centurie (i.e. 353 Quatrains). Two copies of this edition have survived:

- Copy in the Bibliothèque Municipale d ' Albi , Rochegude Fund 12426R. Facsimile edition: Les Prophéties. Lyon, 1555 Amis de Michel Nostradamus, Lyon 1984

- Copy in the Austrian National Library , Vienna, 245154-A FID 44-132. Edition: Pierre Brind'Amour * Nostradamus * Les Premieres Centuries ou Propheties (edition Marc Bonhomme de 1555) Edition et commentaire de l'Epitre a Cesar et des 353 premiers quatrains . Droz, Geneva 1996, ISBN 2-600-00138-7 .

- Both editions differ from each other, although both were printed on May 4, 1555.

- 1557, La grand 'pronostication nouuelle, auec portenteuse prediction pour l'an 1557, composee par maistre Michel Nostradamus, docteur en medecine, de Salon de Craux en Prouence, contre ceux qui tant de foys l'ont faict mort , brochure, printed by Jacques Kerver, Paris, preserved in the Bibliothèque Arbaud, Aix-en-Provence.

- 1557, Les Propheties de M. Michel Nostradamus , Lyon, in Antoine du Rosne. Three examples are known:

- Copy in the University Library of Utrecht (printed September 6, 1557) with the preface to the son César and the Centuries 1-5, 99 quatrains of the 6th century, one unnumbered in Latin, 42 quatrains of the 7th century (i.e. 642 quatrains) , ended with the word FIN . Facsimile edition: Éditions Michel Chomarat, Lyon 1993

- Copy in the Széchényi National Library , Budapest, Ant. 8192 (printed November 3, 1557) without the quatrain in Latin and the quatrains 41 and 42 of the 7th century (i.e. 639 quatrains)

- Copy in the Russian State Library , Moscow, identical to the Budapest copy

- One copy was in Munich until it was removed on Hitler's orders in 1942 , and has been missing ever since.

- 1557, Traité sur le remède contre la peste et toutes les fièvres

- 1557, Paraphrase de C Galen ( Galenus ), also in Antoine du Rosne, Lyon.

- 1558, alleged publication of further prophecies * the preface to King Henry II (dated June 27, 1558) and the Centuries 8-10. No copy of this edition has survived so far; reference is only made to it in later publications * Lyon 1568 (below), Lyon 1605, Troyes c.1611, Lyon 1627, Lyon 1640, Lyon 1644, Rouen 1649, Leiden 1650, Amsterdam 1667 and 1668, Paris 1668. The edition must thus (as the last edition during Nostradamus's lifetime) can be assumed to be hypothetical. A number of editions with the printed year 1566 are known to be forgeries, but most of them date from the 18th century .

- 1559, Les signification de l'eclipse qui sera 16 septembre , Paris

- 1561, Le remède très utile contre le peste (partially), Paris

- 1568, Les Propheties de M. Michel Nostradamus - dont il y en a trois cens qui n'ont encores iamais esté imprimées , with Benoist Rigaud in Lyon; first (surviving) publication of Centuries 8-10 * Preface to the son César, Centurie 1–6, Quatrains 1–42 of the 7th Century, followed by the word FIN , letter to King Henry II, Centurie 8-10 ( with the claim that these have never been printed before!) (ie 942 quatrains). Several prints have survived, the editions marked “A” and “X” seem to be the most authentic.

literature

swell

- Jean-Aimé de Chavigny: La première face du Ianus François… Les Heritiers De Pierre Rovssin, Lyon 1594.

- Jean Dupèbe: Nostradamus - Lettres Inédites. Geneve 1983.

- César de Nostredame: Histoire et chronique de Provence. Lyon 1614. Reprint: Laffitte, Marseille 1971.

- Jehan de Nostredame: Les vies des plus célèbres et anciens poètes provençaux. Lyon 1575. Reprint: Olms, Hildesheim 1971.

- Laurens Videl: Declaration of abus, ignorances et seditions de Michel Nostradamus. Pierre Roux, Avignon 1558.

Secondary literature

- Robert Benazra: Repertoire chronologique Nostradamique (1545-1989). Editions de la Grande Conjonction, La Maisnie, Paris 1990, ISBN 2-85707-418-2 .

- Pierre Brind'Amour: Nostradamus astrophile. Les astres et l'astrologie dans la vie et l'oeuvre de Nostradamus. Pr. De l'Univ. d'Ottawa, Ottawa 1993, ISBN 2-7603-0368-3 .

- Pierre Brind'Amour: Nostradamus: Les premières Centuries ou Prophéties. Droz, Geneva 1996, ISBN 2-600-00138-7 .

- Raoul Busquet: Nostradamus. Sa famille, son secret. Fournier-Valdès, Paris (1950).

- Bernard Chevignard: Présages de Nostradamus. Présages en vers (1555–1567) 1ère éd. complète, Présages en prose (1550–1559) 1ère éd. (version Chavigny). Ed. du Seuil, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-02-035960-X . (Partial edition of Nostradamus' prophecies from the restored manuscript by Chavigny)

- Michel Chomarat: Bibliography Nostradamus. XVIe – XVIIe – XVIIIe siècles (= Bibliotheca bibliographica Aureliana. Vol. 123). Valentin Koerner, Baden-Baden 1989, ISBN 3-87320-123-2 . (authoritative bibliography of early editions of the works of Nostradamus)

- Jean-Paul Clébert: Prophéties de Nostradamus. Les Centuries: texte intégral (1555–1568). Dervy, Paris 2003 (extensive analysis and text comparison of all quatrains)

- Michel Dufresne: Dictionnaire Nostradamus. Définitions, fréquence et contextes des six mille mots contenus dans les Centuries (édition 1605) de Nostradamus. Les Éditions JCL, Chicoutimi (Quebec) 1989, ISBN 2-920176-54-4 . (etymological dictionary of the terms used in the 10 Centuries)

- Jean Dupèbe: Nostradamus: Lettres inédites (= Travaux d'humanisme et Renaissance. Vol. 196). Droz, Geneva 1983

- Elmar R. Gruber : Nostradamus: his life, his work and the true meaning of his prophecies. Scherz, Bern 2003, ISBN 3-502-15280-2 .

- Edgar Leoni: Nostradamus - Life and literature. Including all the prophecies in French and English ... A critical biography. 2 vols. Nosbook, New York, NY 1961. New edition: Nostradamus and his prophecies. Bell, New York, NY 1982, ISBN 0-517-38809-X .

- Peter Lemesurier: The Nostradamus Encyclopedia. St. Martin's Press, New York 1997, ISBN 0-312-17093-9 .

- Peter Lemesurier: Nostradamus. The Illustrated Prophecies. O Books, Winchester 2003, ISBN 978-1-903816-48-6 .

- Peter Lemesurier: The Unknown Nostradamus. O Books, Winchester 2003, ISBN 1-903816-32-7 .

- Edgar Leroy: Nostradamus, ses origines, sa vie, son oeuvre. Trillaud, Bergerac 1972. New edition: Lafitte, Marseille 1993, ISBN 2-86276-231-8 . (first biography on archival basis)

- Roger Prévost: Nostradamus, le mythe et la réalité. Un historien au temps des astrologues. Laffont, Paris 1999, ISBN 2-221-08964-2 . (Examining the prophetic sources of Nostradamus)

- Frank Rainer Scheck: Nostradamus. dtv, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-423-31024-3 . (brief but serious biography)

- Louis Schlosser: La vie de Nostradamus. Belfond, Paris 1985

- Ian Wilson: Nostradamus: The Evidence. Orion, London 2003, ISBN 0-7528-4279-X .

Web links

- Link catalog on the topic of Nostradamus at curlie.org (formerly DMOZ )

- Literature by and about Nostradamus in the catalog of the German National Library

- Nostradamus: All facsimiles of the first five original editions

- Robert Benazra: Espace Nostradamus (website with academic forum; French)

- Estudes Nostradamiennes ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (French / English)

- Patrice Guinard: Nostradamica. International Research on Nostradamus Works (academic forum with articles in French, Spanish and English)

Individual references and comments

- ↑ Leroy, 1972/1993, pp. 32-51.

- ↑ Leroy p. 57 (see literature).

- ↑ Brind'Amour, 1993, p. 118.

- ↑ a b c Leroy, 1972/1993, p. 61.

- ↑ Scheck, 1999, p. 45.

- ↑ Dupebe, 1983, passim

- ↑ quoted from Jean Dupèbe: Nostradamus - Lettres Inédites , Geneve 1983, p. 85.

- ↑ Leroy, 1972/1993, pp. 66-69; Wilson, 2002, pp. 45-47; Gruber, 2003, pp. 52-53. Whether he served as a doctor or a pharmacist in Marseille cannot be proven: only Gruber calls him “plague doctor”.

- ↑ Chevignard, 1999, passim ; Brind'Amour, 1993, p. 24.

- ↑ Leroy, 1972/1993, pp. 80-84.

- ↑ Cesar de Nostredame, 1614, pp. 801-812.

- ↑ Leroy 1972/1993, Clébert 2003 and Gruber 2003 assume it. On the basis of several circumstantial evidence, Brind'Amour 1993 (p. 114 f) considers it likely. Benazra 1990 thinks so. Wilson 2003 (p. 310 f) doubts it, due to insufficient sources. Lemesurier 2003 (p. 24 f) finds no evidence.

- ^ Pierre Brind'Amour: Nostradamus: Les premières Centuries ou Prophéties . 1996, p. 117, note 34.

- ↑ BIU Montpellier, Register S 2 folio 87. Facsimiles from Michel Chomarat: Cahiers Michel Nostradamus. Association des Amis de Michel Nostradamus, No. 2 (February 1984), p. 20 and Peter Lemesurier: The Unknown Nostradamus 2003, p. 25.

- ↑ Michel Nostradamus: Traité des fardemens et confitures , otherwise known as Le vray et parfaict embellissement de la face and Excellent & moult utile opuscule… , 1555 (foreword).

- ↑ City archives for June, 1554: Me Micheou de Nostredame, six ecus d'or sol pour son entree dans la convention faicte ...

- ↑ Laurens Videl: Declaration des abus, ignorances et seditions de Michel Nostradamus , 1558, p. 22.

- ↑ Dupèbe: Nostradamus: Lettres inédites 1983 (passim) and Lemesurier The Unknown Nostradamus , 2003 S. 253rd

- ↑ Histoire & Chronique de Provence 1614, pp. 801-812.

- ↑ Leroy Nostradamus, ses origines, sa vie, son oeuvre. 1972, pp. 8, 11.

- ↑ Brind'Amour: Nostradamus astrophile 1993, p. 23.

- ↑ Brind'Amour, Nostradamus astrophile 1993; Jacqueline Allemand, Cherche ton étoile dans le ciel de l'avenir , Maison de Nostradamus o. J., p. 1; Lemesurier, The Unknown Nostradamus ' 2003; Jean-Paul Clébert: Prophéties de Nostradamus , 2003, pp. 13-14; Will 1566; see also the plaque on his house in the drawing room.

- ↑ Jacqueline Allemand, 500 ans d'apothicaire , Maison de Nostradamus 1995, p. 10; Brind'Amour 1993, pp. 110-111.

- ^ Edgar Leroy: Nostradamus, ses origines, sa vie, son oeuvre , 1972/1993. P. 57.

- ↑ Laurens Videl: Declaration des abus, ignorances et seditions de Michel Nostradamus , 1558, p. 10.

- ^ Nostradamus: Les Propheties , Antoine du Rhone, Lyon 1557, p. 114.

- ↑ Brind'Amour: Nostradamus astrophile , 1993, pp. 329-331.

- ↑ Examined in detail in Pierre Brind'Amour: Nostradamus astrophile , 1993, p. 331.

- ↑ Brind'Amour: Nostradamus astrophile , 1993. p. 330; Gruber, 2003, p. 69 f.

- ↑ Elmar Gruber, Nostradamus: his life, his work and the true meaning of his prophecies , 2003, pp. 314–348.

- ↑ Videl: Declaration des abus, ignorances et seditions de Michel Nostradamus , 1558. p. 6. See also Gruber, 2003, p. 68 ff.

- ↑ See his handwritten Orus Apollo .

-

↑ Richard Roussat: Livre de l'etat et mutations des temps . Lyon 1550, p. 95 . B. Brinette: Richard Roussat: Livre de l'etat et mutations des temps, introduction et traductions . (n.d. [1550]). P. Lemesurier: The Unknown Nostradamus . O Books, Alresford 2003, pp.

53 . Nostradamus: The Illustrated Prophecies . O Books, Alresford 2003, pp.

382 . - ↑ Chomarat & Laroche, Bibliography Nostradamus , 1989, pp. 63-211; Benazra, 1990, pp. 91-634.

- ↑ Scheck, 1999, 103 f.

- ↑ Max Dessoir : Vom Jenseits der Seele: The Secret Sciences in Critical Consideration , Stuttgart 1917 (reprint Stuttgart 1967), p. 127.

- ↑ See Chevignard, 1999, passim

- ↑ See Bibliotheque Nostradamus. In: Propheties On Line. Retrieved July 4, 2016 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Nostradamus |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Notredame, Michel de |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | French doctor and seer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 14, 1503 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Saint-Rémy-de-Provence , Provence |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 2, 1566 |

| Place of death | Salon de Provence |