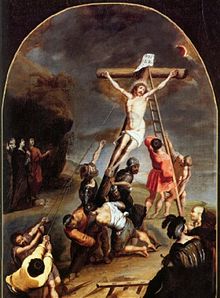

Darkness at the crucifixion of Jesus

The three-hour darkness at the crucifixion of Jesus is an element of the passion story of the Synoptic Gospels in the New Testament . In Christianity, darkness is generally understood as a miracle and, against the background of the Old Testament, is interpreted primarily as a sign of judgment.

Their historicity is the subject of ongoing discussion. Already in antiquity it was declared to coincide with a natural event, such as an occultation . A solar eclipse would already have been perceived as a miracle by contemporaries, because solar eclipses only take place at a new moon , but Jesus was crucified on or shortly before a Passover festival . Passover is always celebrated at or near the full moon .

Christian historians and theologians compared the darkness to reports of other eclipses or dark periods of time. Attempts have also been made to date the crucifixion precisely to the present day. Because of the darkness mentioned in the Passion Reports, astronomical calculations were also used; However, the decisive attempts at dating are based on ancient sources (especially government years) and calendar calculations.

Biblical evidence

Passion reports

The synoptic Gospels consistently report that darkness fell during the crucifixion ( skotos egeneto , Greek : σκότος εγένετο). On the first day of Passover, it lasted from noon to 3 p.m. ('sixth to ninth hour' according to ancient counting):

"But from the sixth hour onwards there was darkness over the whole land until the ninth hour."

“And it was already about the sixth hour; and there was darkness over all the land until the ninth hour, 45 because the sun ceased [to shine]; but the curtain of the temple was torn in two. "

No reason is given for the darkness or for the eclipse of the sun. Nor is it interpreted. The Gospel of John does not mention the process.

Comparable Old Testament statements

The closest synoptic statements are to a place in the prophet Amos ( Am 8,8-9 ELB ), where a sunset or an eclipse in the middle of the day is announced in connection with an earthquake:

“ 8 Shouldn't the earth tremble because of this, and everyone who lives on it mourn? - that it rises as a whole like the river and rises and sinks like the river of Egypt? 9 In that day, says the Lord GOD, I will make the sun go down at noon, and I will bring darkness over the earth in the light of day. "

At the beginning of the book of Amos an earthquake is mentioned that occurred two years later ( Am 1.1 ELB ); this tremor is usually understood as the fulfillment of prophecy. The book Zechariah , which was written later, also refers to this earthquake ( Zech 14,5 ELB ).

The prediction of Amos is related to a court announcement to the people of Israel ( Am 8,1-13 EU ), in which the mourning for one “only one” also plays a role. With a view to the earthquake of Mt 27.52 EU , this passage in historical-critical exegesis is often seen as the background of ideas for the New Testament presentation. According to traditional interpretation, the text is understood as a prophetic prediction of the darkness at the crucifixion.

To what extent the following passages are to be understood as real-cosmic or metaphorical , i.e. as pictorial language, cannot always be determined with certainty.

A real-cosmic eclipse (of the sun, the moon or even the stars) as a judgment act of God seems z. B. to be available in the following places:

- Gen 15.12 ESV judgment announcement to Abraham

- Ex 10.21–23 ELB darkness against the Egyptians when theyleave ; and reminder of it: Jos 24.7 ELB

- Isa 13,9-10 ELB On the day of the Lord the stars, sun and moon will no longer shine.

- Hes 30,18 NIV ; Eze 32.7 ELB

- Joel 2.10 ELB ; Joel 3.4 ELB ; Joel 4.15 ELB .

The following passages are to be understood as metaphorical speech:

- 1 Sam 2,9 ELB wicked end in darkness,

- Hi 12.25 ELB ; Hi 15.30 ELB ; Hi 18.6 ELB ; Hi 19.8 ELB ; Hi 20.26 ELB ; Hi 24.17 ELB and other

- Ps 35.6 ELB ; Ps 44.20 ELB ; Ps 69.24 ELB ; Ps 82.5 ELB ; Ps 105.28 ELB ; Ps 107.10 ELB and others

- Isa 45,7 ELB : God creates light and darkness, gives peace and creates disaster ( parallelism of darkness and disaster)

- Isa 50,3 ELB Judgment of God to his people: "I dress the heavens in black black and put sackcloth on them as clothing."

- At 5.18-20 ELB ; Nah 1.8 tbsp ; Zef 1.15 tbsp

Comparable New Testament statements

The darkening of the sun as a judicial act is found in Rev 8.12 ELB (4th trumpet: darkness during a third of the day), Rev 9.2 ELB (5th trumpet: “a smoke from the well of the abyss darkens the sun and the Air ") and in Rev 16,10 ELB (5th bowl of anger is poured" on the throne of the beast ", whereby his kingdom is darkened).

Interpretation of darkness

The darkness at the crucifixion, along with the tearing of the temple curtain (Mk 15:38) and the resurrection of the saints (Mt 27, 51–53), is one of the motifs that suggest an eschatological interpretation of the death of Jesus. For Jesus "death and resurrection marked the dawn of the great day of God." This interpretation was rooted in Jesus' own understanding of his death, which he saw "as part of the eschatological drama that was now unfolding."

"The natural darkness here confirms in a supernatural way the blackness of what is happening on the historical level", namely the crucifixion (François Bovon).

This sign reminded Jewish listeners and readers both of the darkness of the Theophanien (e.g. on Sinai ) and of the day of Yahweh , especially the "day of wrath". It reminded Greek and Roman readers that "cosmic tremors or signs from heaven ... underscore the great importance of the death of princes, heroes, even gods (Isa 13:10; Jer 4:23)." The darkness was one of the plagues in Egypt (Ex 10.22) and appears in the prophets as a judgment of the end times (Isa 13.10, Eze 30.3 and 32.7-8, Joel 2.2, 10.31, 3.15, Am 5.18, Sach 14.6).

Gospel of Matthew

Matthew also describes the crucifixion from the point of view of the tragedy that Israel rejects its Messiah and the Gospel and that scripture is thereby fulfilled. The crucifixion casts dark shadows on the entire narrative of the life of Jesus. The darkness can be seen as a harbinger of the approaching judgment against Jerusalem and Israel, whose inhabitants called it out: His blood be on us and our children! (Mt 27.25)

Gospel of Mark

Mark understands the moment of crucifixion as a moment of divine revelation: in his death Jesus, the righteous Son of man and obedient servant, can be fully grasped in his worth and recognized as the Son of God. The Roman centurion said it: Truly, this man was the Son of God! (Mk 15:39). The darkness marks the transition to the new order of salvation after the temple curtain is torn.

Gospel of Luke

Luke adds that the sun has stopped (Greek: εκλείπειν ), which refers to the sunlight that was apparently missing. Ekleipein is the common term for a solar eclipse. The majority text , many old text witnesses and probably Origen also pass on the word eskotistä (εσκοτίσΘη): The sun “was darkened”. In Luke, too, the darkness is not explicitly interpreted. The fact that the power of darkness is at work is already expressed by the Gospel when Jesus was arrested (Lk 22:53) in his word to those in power: This is your hour and the executive power (εξουσία) of darkness. The double keyword connection is obvious. With this, Jesus announced the visible eclipse.

By placing the tearing of the temple curtain next to the darkness (although his sources begin shortly after Jesus' death), Luke creates an implicit interpretation for both: Just as darkness tears the day in half, the (inner) curtain in the temple tears in two halves. While the darkness reigns outside and the judgment of God comes upon Jesus, inside the access to God's presence opens. Both have universal meaning.

The evangelist had taken the darkness for "a cosmic sign", "which underlines the importance of the death of the Messiah Israel" and less its meaning. According to Luke's conception, it probably extended over the entire inhabited “earth” (γή), because the evangelist wanted to demonstrate Jesus' importance for the whole world through his two books, Luke and Acts of the Apostles . On the other hand, both Keener and Liefeld understand “land” in the local sense as a designation for Israel or Judea (likewise the Gospel of Peter , 15).

Early Christian texts

The Gospel of Peter describes that around noon it was total darkness in Judea and that many people set out with lamps, “because they thought it was night, but they kept falling down” (chap. V, verse 15 + 18). At the ninth hour the sun began to shine again (chap. VI, verse 22). The scribes, Pharisees and elders would have said to one another, especially with regard to the darkness: "If these extremely great signs have occurred at his death, see how righteous he was" (Chapter VIII, verse 28).

The first part of the Gospel of Nicodemus (4th century) depicts the process and execution of Jesus. A multitude of perceptible phenomena that accompanied the crucifixion are mentioned. According to chap. 11 the eclipse began around noon, lasted three hours, and was caused by the darkening of the sun. It also notes that Pilate and his wife were troubled by a report of the incidents (11.2). The Jews he summoned said it was an ordinary solar eclipse .

In the third part of the scriptures, the descent of Christ into hell (also known as the “descent into hell”), the many dead are described who rose and appeared to many people in Jerusalem shortly after the resurrection of Christ. Finally, the alleged interrogations of the emperor in Rome and the subsequent decree are reproduced, which ordered severe penalties for Pilate and the Jews for causing the darkness and the earthquake that affected the whole earth.

In the letter of Pontius Pilate to Tiberius , part of the Latin version of the Gospel of Nicodemus, it is said that darkness began at the sixth hour, covered the whole world (the inhabited world) and from evening until the next morning the moon looked like blood.

In letters under the name of Dionysius Areopagita , the author ( pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita ) claims that he observed a solar eclipse from Heliopolis at the time of the crucifixion . The eponymous Dionysius (Acts 17.34) came from Athens and is said to have received a classical Greek upbringing. He studied astronomy in Heliopolis, where he and his friend Apollophonus are said to have witnessed the solar eclipse at the time of Jesus' death. He is said to have said during the darkness: "Either the Creator of the whole world suffers now or the visible world is coming to an end."

Other apocryphal writings give a shorter account of the darkness. In the Acts of John (Acta Ioannis) there is the statement that darkness began at the sixth hour and covered the whole earth.

Ancient historians

The Christian historian Sextus Julius Africanus wrote around 220 that the non-Christian chronicler Thallus had wrongly described the darkness as a solar eclipse:

“In the third book of the histories Thallus calls this eclipse a solar eclipse . It seems to me, against reasonable understanding. "

Africanus argues against Thallus that Jesus was crucified on a spring full moon and then there could have been no solar eclipse. Because the Passover festival is always celebrated with a full moon ( Lev 23.5 EU ), which excludes the sun from being covered by the moon.

From this it is concluded that Thallus knew a Passion tradition that portrayed darkness as a natural wonder, while as a non-Christian he wanted to refute this interpretation by dismissing it as a (natural) solar eclipse. However, it is not certain whether Thallus himself referred to the crucifixion. Africanus also quotes the chronicler Phlegon von Tralleis (2nd century): “Phlegon reports that there was a complete solar eclipse during the reign of Emperor Tiberius, with a full moon from the sixth to the ninth hour”.

The church historian Eusebius of Caesarea (264–340) quotes Phlegon in his chronicle as saying that during the fourth year of the 202nd Olympiad (32/33 AD) “a great solar eclipse occurred at the sixth hour that exceeded all previous ones, turned the day into such a nocturnal darkness that the stars were visible in the sky and the earth in Bithynia moved, so that many buildings in the city of Nicaea collapsed. ”It was believed that this was the solar eclipse of November 24th, 29th . Although this corresponds to the "first" year of the Olympics, it can be traced back to a typographical error from Α '("1st") to Δ' ("4th"). In 2005, the seismologist Nicolas Ambraseys showed that the sources did not mention Jerusalem in connection with the earthquake.

In his Apologeticum (AD 197), Tertullian tells the story of the darkness that began at noon during the crucifixion. Anyone who did not know the prediction "doubtlessly thought it was a darkness". Tertullian claims that the evidence is still available: "You yourself still have the record of the worldwide mark in your archives."

The early historian and theologian Rufinus of Aquileia (~ 345–410), who continued the ecclesiastical history of Eusebius, gave part of the defense speech of Lucian of Antioch († 312, martyrdom) against Emperor Maximinus Daia . Like Tertullian, Lukian was convinced that an account of the darkness at the crucifixion could be found in Roman records. James Ussher (1581–1656) narrated Lukian's corresponding statement before Maximinus as follows: "Research your writings and you will find in the time of Pilate, when Christ suffered, that the sun was suddenly taken away and a darkness followed."

The Christian historian Paulus Orosius wrote around 417 that Jesus “willingly surrendered himself to suffering, but was arrested and nailed to the cross by the disbelief of the Jews when a very great earthquake took place all over the world, rocks and mountains burst and the most of the largest cities collapsed as a result of this extraordinary violence. On the same day, at the sixth hour of the day, the sun was also darkened and a hideous night suddenly overshadowed the land, as it was said: 'an indecent age feared the eternal night.' Moreover, it was absolutely clear that neither the moon nor the clouds stood in the way of the sunlight, so it is reported that on that day the moon, when it was 14 days old, and the entire sky region in between [scil. between him and the sun] was furthest from the face of the sun, and that the stars shone all over the sky then, in the hours of the day, or rather: in that terrible night. This confirms not only the authority of the Holy Gospels, but even some books of the Greeks. "

Historical question

The early Christian texts only seem to vary the information in the Gospels, embellish them and combine them with Old Testament material. Apart from Peter's Gospel, which describes the character of darkness, they provide hardly any evaluable information that goes beyond what is said in the Gospels.

In the 19th century, the atheist Kersey Graves argued that the biblical account was implausible and ridiculous. Because there is a lack of statements about a darkness at the crucifixion in the works of Seneca and Pliny . The lack of contemporary accounts and the silence of the Gospel of John are still being discussed today. Plausible reasons can be given for the silence, however, and John also omitted other elements of the synoptic Passion reports (the word from Ps 22: 2, the cry of abandonment immediately before death, etc.) and added other elements.

The answer to the historical question depends essentially on whether the note from Luke (the sun has 'gone out') is viewed as a description of a total solar eclipse. If you do so, the darkness appears as a literary invention that is supposed to enhance the death of Jesus or show the importance of his death for the entire cosmos. From an astronomical point of view, the historically relevant solar eclipses in Jerusalem would hardly have had the effect that would explain the phenomenon mentioned by the synoptics (see Mark Kidger below). This is especially true for the lunar eclipses in question (cf. Schaefer's criticism of Humphreys and Waddington below). In addition, the long duration of the biblically attested eclipse (about three hours) is occasionally used as an argument against the historicity of a solar eclipse, cf. but the section below: Similar reports about the duration of the darkness . The fact that no blood-red moon is mentioned in the Passion reports speaks against the thesis of a lunar eclipse. The fact that Jesus was crucified at the time of the Passover festival, which is always celebrated at the full moon, speaks against the explanation of darkness by means of a solar eclipse.

HJ MacAdam (in the article “Darkness”, Σκότος) considers that the solar eclipse of November 24th 29 could have caused Luke to interpret the tradition (Gospel of Mark) before him and to explain it with the aid of a solar eclipse. The formulation that "the sun went out" (του ηλίου εκλίποντος) definitely comes from Lukas, of which Bovon is also convinced, who considers a calculation error in Lukas and whose memory of the solar eclipse of November 24th, 29th So assuming that a solar eclipse is reported, the tearing of the temple curtain (according to all synoptics), the earthquake and the raising of the dead (Matthew) are all the more considered fictional elements within the essentially historical report.

If one assumes another, non-astronomical cause for the eclipse of the sun, the extra-biblical historical evidence is rather weak (indirectly from Thallus: after 52 AD; from Tertullian: around 197 AD, Phlegon von Tralleis and the Gospel of Peter: in 2nd century), but does not have to be provided as it may have been a regional eclipse. It can be acknowledged as a sufficiently documented, naturally inexplicable occurrence.

Carson considers it pointless to discuss the various possible causes of the eclipse, "not because it did not happen, but because we do not know how it happened."

Theologically, "the darkness appears as a symbol and accompaniment of the divine judgment", regardless of whether it is considered historical. It is seen as the actual fulfillment of court announcements like those in Amos 8,9, Joel 2,10; 3.4; 4.15 and so on be understood or - depending on the worldview or theological orientation - as a literary expression of how the early Christian understood the death of Jesus.

Explanations for the darkness

Declaration as a miracle

Because it was known in the Middle Ages that solar eclipses cannot take place during the Passover (always celebrated on full moons), but only at the new moon, the eclipse at the crucifixion of Jesus was viewed as a miraculous sign and hardly as a natural event. The astronomer Johannes de Sacrobosco wrote around 1230 in his Tractatus de Sphaerahis that "darkness is not natural, but rather miraculous and opposed to nature."

Total solar eclipse

Historical reports of the sun 'extinguishing' that lasted more than half an hour have actually been attributed to total solar eclipses. So there are z. B. Reports from the T'ang Dynasty and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle of the one-hour solar eclipse in the year 879. They are included in the total solar eclipse of October 29, 878.

On Passover (15th Nisan) or in its temporal vicinity, i.e. at the time of Jesus' crucifixion, no solar eclipse can have occurred because it only occurs during new moon phases and there is always a full moon on 15th Nisan.

If one moves away from the Passover time as the crucifixion date, the solar eclipses in question in those years are too weak to be responsible for the darkness: the astronomer Mark Kidger described the total eclipse of November 24, 29 as the one with the greatest geographical proximity to the place of crucifixion. Your umbra passed slightly north of Jerusalem at 11:05 a.m. (see NASA's diagram for this umbra). Kidger was able to show that the maximum degree of darkness for Jerusalem was only 95%. The degree of darkening was not perceptible for people outdoors ("unnoticeable for people outdoors"). According to his calculations, this darkness was total in Nazareth and Galilee (1 min. 49 sec.). He concluded that the inhabitants of Jerusalem had neither the need nor the time to light their lamps because of this solar eclipse, as described in the Gospel of Peter . Such behavior could only be explained by a much longer period of darkness during a total solar eclipse.

Solar eclipses are too short to be considered for the darkness at the crucifixion (but see below Chapter 7: Similar Reports ). Because the duration described exceeds the effect of a total solar eclipse by at least ten times. In principle, a solar eclipse can never be longer than seven and a half minutes in total. The eclipse of November 3, 31 lasted a maximum of one minute and four seconds, that of March 19, 33 only four minutes and six seconds. Neither of them was total when they passed over Jerusalem. A lengthy total eclipse that occurred somewhat close in time to the year of the crucifixion occurred on July 22nd, 27; it lasted six minutes and 31 seconds at most in Judea.

lunar eclipse

The indication of Petrus that the moon transform into blood ( Acts 2,20 ELB ) served the derivation of the date of the crucifixion. The crucifixion took place at the time of the feast of Passover, i. H. in the middle of the lunar month with a full moon.

In the Acts of the Apostles Acts 2.20 ELB Peter mentions in connection with the prophecy from Joel Joel 3.4 ELB that “the sun is to be changed into darkness and the moon into blood”. A "moon of blood" is a common name for a lunar eclipse because of the reddish color of the moon, which is caused by the refraction of light in the earth's atmosphere (residual light reflection). Bible commentators disagree on the exact meaning of Peter’s statement. Astronomer Martin Gaskel argued that a lunar eclipse would have attracted significant attention on the day of the crucifixion.

Humphreys and Waddington

In 1985, Colin J. Humphreys and WG Waddington of Oxford University published their reconstruction of the Jewish calendar for the first century AD. According to this, Friday, April 3, 33, would have been the date of the crucifixion. In addition, they also reconstructed the scenario of a lunar eclipse for this day: “This eclipse was visible in Jerusalem when the moon rose. ... The beginning of the darkness was invisible in Jerusalem because it was below the horizon. It began at 3:40 p.m. and reached its maximum at 5:15 p.m. with 60% coverage of the moon, which in turn was below the horizon for Jerusalem. ”It was visible in Jerusalem from about 6:20 p.m. to 6:50 p.m. (at the beginning of the Sabbath or Passover in year 33), with about 20% of the lunar disk in the umbra of the earth.

The fact that no gospel mentions a red moon is the result of a copyist who incorrectly corrected the text. The authors conclude that the blood-red moon probably refers to a lunar eclipse. This interpretation is consistent and fits April 3, 33 as the date of the crucifixion.

Criticism of Humphreys and Waddington

The assumption of a text correction that someone wrote “sun” instead of “moon” is hypothetical. The explicitly mentioned darkening of the sun is also not explained ( Lk 23.44–45 EU ).

Astronomer Bradley E. Schaefer disagreed with Humphreys and Waddington about the visibility of the lunar eclipse, relying on his computerized calculations of celestial light phenomena. No lunar eclipse was visible during the crucifixion. The Brit Clive Ruggles came in 1990 to the same result as Schaefer.

Other explanations

Some explained the darkness at the crucifixion by means of a thick cloud cover. Another natural explanation is one of Chamsin caused -Wind dust storm, which tends to occur in Israel from March to May

Waiver of an explanation

DA Carson considers it "useless to argue or reason about whether the eclipse was caused by a solar eclipse of three hours (!) Or atmospheric conditions, caused by a sirocco or something else", because we simply do not have enough know the origins of darkness. "The evangelists are mainly interested in the theological implications that arise from historical phenomena."

Similar reports about the length of the darkness

While total eclipses in fact never last more than a few minutes, the duration in the early sources is often given as two to three hours. This applies, among other things, to the eclipse of Reichersberg in 1241. Modern it has been determined to last just under three and a half minutes. Francis Richard Stephenson suspects that the synoptic accounts of the Passion of Christ were the inspiration. However, such long periods of time are also known from reports from other cultures. One possible explanation for the extraordinary duration is the shocking impression that such a rare and inexplicable event can leave.

The eclipse visible in large parts of southern Europe on June 3, 1239 was observed in Coimbra , Toledo , Montpellier , Marola , Florence , Siena , Arezzo , Cesena and Split . Their duration was usually given as several hours. The monk and naturalist Ristoro d'Arezzo made the world's first attempt to measure the duration: According to this, the covering lasted as long as it takes a man to walk 250 paces, which corresponds to the assumed five minutes and 45 seconds.

Dating the crucifixion

The darkness at the crucifixion played a minor role in trying to date the crucifixion. Various considerations about the year of the crucifixion were combined with astronomical and calendar determinations of the days from when the sickle of the new moon was visible from Jerusalem. Because this was taken by the Jews as the beginning of their month (lunar month), i.e. as 1st Nisan . This made the day of the crucifixion likely. Common estimates came on April 7, 30, April 3, 33, and April 23, 34.

Extra-biblical accounts were included in determining the year of the crucifixion . Eusebius linked the darkening of the sun with the 18th year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius and the earthquake as the year of Jesus' crucifixion. Since Tiberius (* 42 BC; † 37 AD) ascended the throne in 14 AD, his 18th year of reign fell on the year 32 or - if you take the Jewish calendar into account - between spring 32 and spring 33. Also the eclipse mentioned by Phlegon von Tralleis brings us to the year 32 or 33. The fourth year of the 202nd Olympiad ran from summer 32 to summer 33. Because the first Olympiad was 776 BC. And then every four years.

Isaac Newton calculated the day of the crucifixion by considering the Jewish and Julian calendars, as well as the location of the Jewish feast days on the autumn equinox . On this basis, he adopted Friday ( Nisan 14 ) as the day of the crucifixion. According to Newton, due to a postponement rule, according to which some holidays were postponed to the respective Shabbat in order not to have several holidays consecutively, the 14th Nisan fell on Wednesday, March 28th in the year 31, and on Monday, April 14th in the year 32 , and only in years 33 and 34 on a Friday. Newton first set Friday (33 or 34) and then April 23, 34 as the most likely date of the crucifixion. His basic assessment was confirmed with modern methods. Astronomer John Knight Fotheringham similarly confirmed the crucifixion date.

Astronomers Bradley E. Schaefer and John Pratt, using various computer simulations based on the approach originally chosen by Isaac Newton , independently of one another came to the same date for the crucifixion, namely Friday, April 3, 33 as the most likely date.

See also

- Jesus Christ # suffering and death on the cross

- Good Friday

- Eschatology

- Computus

- Archaeoastronomy

- International heliophysical year

- Solar eclipse

- Roman triumph

literature

- Richard Carrier: Thallus and The darkness at Christ's death . In: Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism (JGRChJ) 8 (2011/12), pp. 185–191.

- Arne Eickenberg: The sixth hour - Synopsis on the historical origin of the miracles and natural disasters in the Passion of Christ. Ludwig, Kiel 2015, ISBN 978-3-86935-193-3 .

- Carsten Peter Thiede , Matthew d'Ancona: The Jesus Papyrus. Doubleday, New York 1996, ISBN 0-385-48898-X , pp. 59-64, pp. 101-127, pp. 135-137.

- MR James: The gospel of Nicodemus, or Acts of Pilate. In: The apocryphal New Testament . Clarendon Press: Oxford 1924, accessed July 8, 2014 (Wesley Center for Applied Theology Noncanonical Homepage) (English translation)

- Hans Zimmermann (ed.): Nikodemus-Evangelium, Pilatusakten (Acta Pilati) , Görlitz 2009, accessed on July 8, 2014. (Greek text according to Konstantin von Tischendorf : Evangelia Apokrypha. Leipzig 1876, in transliterated form and German translation)

Remarks

- ^ Walter L. Liefeld: Luke. In: Frank E. Gaebelein (Ed.): The Expositor's Bible Commentary , Vol. 8, Grand Rapids 1984, p. 1045.

- ↑ Dominic Rudman: The crucifixion as chaoskampf: A new reading of the passion narrative in the synoptic gospels , in: Biblica (Journal), 84, pp. 102-107. [1]

- ↑ Wolfgang Fritzen: Forsaken by God? The Gospel of Mark as a means of communication for oppressed Christians , Kohlhammer Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-17-020160-6 , p. 339.

- ^ Herbert Lockyer: All of the Miracles of the Bible , Zondervan Publishing House: Grand Rapids 1971, p. 243.

- ^ Joel B. Green: Art. Death of Jesus , in: Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels , InterVarsity Press: Downers Grove 1992, p. 153.

- ↑ DC Allison, Jr .: The End of the Ages Has Come: An Early Interpretation of the Passion and Resurrection of Jesus , Philadelphia 1985, p. 142.

- ^ François Bovon: Evangelical-Catholic Commentary (EKK) III / 4, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2009, p. 487.

- ^ A b François Bovon: EKK III / 4, p. 487.

- ↑ See Plutarch, De Def Orac 17

- ↑ Craig S. Keener: The Bible Background Commentary , Downers Grove 1993, p. 255.

- ^ DA Carson: Matthew, in: Frank E. Gaebelein (ed.): The Expositor's Bible Commentary , Vol. 8, Grand Rapids 1984, p. 578.

- ^ François Bovon: EKK III / 4, p. 488.

- ↑ Novum Testamentum Graece , 27th edition Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 3-920609-32-8

- ^ François Bovon: EKK III / 4, p. 490.

- ^ François Bovon: EKK III / 4, p. 489.

- ↑ Craig S. Keener: The Bible Background Commentary , Downers Grove 1993, p. 255. - Walter L. Liefeld: Luke , in: Frank E. Gaebelein (Ed.): The Expositor's Bible Commentary , Vol. 8, Grand Rapids 1984 , P. 1045.

- ^ Acts of Pilate, in: Willis Barnston (Ed.): The Other Bible , New York 1984, ISBN 0-06-250030-9 , p. 368.

- ↑ Christ's Descent into Hell, in: Willis Barnston (Ed.): The Other Bible , New York 1984, p. 374.

- ^ The Paradosis, in: Willis Barnston (Ed.): The Other Bible , New York 1984, pp. 378f.

- ^ Pontius Pilate . Bibleprobe.com. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ↑ John Parker: Letter VII. Section II. To Polycarp - Hierarch. & Letter XI. Dionysius to Apollophanes, Philosopher . In: The Works of Dionysius the Arepagite . James Parker and Co., London 1897, pp. 148-149, 182-183.

- ^ Revelation of the Mystery of the Cross, in: Willis Barnston (ed.): The Other Bible , New York 1984, p. 419.

- ↑ Reported by the historian Georgios Synkellos around 800, chronograph 391 .

- ↑ Alexander Loveday: The Four among pagans , in: Bockmuehl, Hagner (Ed.): The Written Gospel , Cambridge University Press 2005, p. 225.

- ^ "Chronicle" , Olympiad 202, translated by Richard Carrier 1999. German-language reference!

- ↑ name = Africanus

- ↑ Nicolas Ambraseys (Νικόλαος Αμβράζης): Historical earthquakes in Jerusalem - A methodological discussion . In: Journal of Seismology, 9 (2005), pp. 329-340. doi : 10.1007 / s10950-005-8183-8 .

- ^ Tertullian, Apologeticum, chap. 21,19 , in: GD Bouw, (1998). The darkness during the crucifixion. The Biblical Astronomer , 8 (84). [2] .

- ^ Rufinus of Aquileia: Church history . Book 9, chap. 6th

- ^ Translation (Engl.) In: James Ussher, L. Pierce: Annals of the World . Green Forest (Arizona) 2007, ISBN 0-89051-510-7 , p. 822.

- ^ Paulus Orosius: The Seven Books of History Against the Pagans , in: RJ Deferrari & H. Dressler, et alii (eds.): The Fathers of the Church , Vol. 50, The Catholic University of America Press .: Washington DC 1964 , 1st reprint 2001, ISBN 978-0-8132-1310-1 , pp. 291f.

- ^ Kersey Graves : The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors , NuVision Publications, LLC 2007, ISBN 1-59547-780-2 , pp. 113-115. {Original edition 1875}.

- ^ Richard Carrier, 1999.

- ↑ So z. B. Robert W. Funk and the Jesus seminar : The Gospel of Luke refers specifically to a solar eclipse, in: The acts of Jesus: the search for the authentic deeds of Jesus. San Francisco 1998. pp. 267-364.

- ^ WD Davies, C. Allison Dale: A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the Gospel According to Saint Matthew , Vol. III (1997), p. 623.

- ↑ Cf. Kelley, Milone and Aveni, who discuss various lunar and solar eclipses in their temporal context and their interpretation in church history and astronomy. David H. Kelley, Eugene F. Milone, AF Aveni Springer: Exploring Ancient Skies: A Survey of Ancient and Cultural Astronomy , February 18, 2011

- ↑ a b Commentary on Matthew , in: Frank E. Gaebelein (Ed.): The Expositor's Bible Commentary , Vol. 8, Grand Rapids 1984, p. 578.

- ↑ David H. Stern: Commentary on the Jewish New Testament , Vol. 1, Holzgerlingen 1996, p. 249.

- ^ GF Chambers: The Story of Eclipses , New York 1908, pp. 110f.

- ^ Robert Bartlett: The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages , Cambridge University Press: Cambridge 2008, pp. 68f.

- ↑ Michael A. Seeds, Dana Backman: Astronomy: The Solar System and Beyond , 2009 ISBN 0-495-56203-3 , p. 34.

- ^ NASA - Eclipse 99 - Eclipses Through Traditions and Cultures . Eclipse99.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on February 17, 2013. Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Retrieved January 17, 2013.

- ↑ Espenak: Eclipse Quotations - Part II . Mreclipse.com. December 6, 1998. Retrieved February 28, 2011.

- ↑ http://eclipse.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEhistory/SEplot/SE0029Nov24T.pdf

- ↑ Mark Kidger: The Star of Bethlehem: An astronomer's View , Princeton University Press: Princeton 1999, ISBN 0-691-05823-7 , pp. 68-72.

- ^ J. Meeus: The maximum possible duration of a total solar eclipse, in: Journal of the British Astronomical Association , 113 (2003), pp. 343-348.

- ^ Five Millennium Catalog of Solar Eclipses . NASA . Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ National weather service

- ↑ CM Gaskel: Beyond visibility: The "Crucifixion eclipse" in the context of some other astronomical events of the times . In: Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society , 25 (1993), p. 1334.

- ^ A b Colin J. Humphreys, WG Waddington: The Date of the Crucifixion , in: Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation, 37 (1985) Archived copy ( Memento of the original from April 8, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet tested. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

-

^ Bradley E. Schaefer: Lunar visibility and the crucifixion . In: Royal Astronomical Society Quarterly Journal, 31 (1) (March 1990), pp. 53-67

Bradley E. Schaefer: Glare and celestial visibility . In: Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 103 (July 1991), pp. 645-660. - ↑ Clive LN Ruggles: Archaeoastronomy - the Moon and the crucifixion . In: Nature, 345, pp. 669-670 (1990).

- ↑ a b c d F. R. Stephenson : Historical Eclipses and Earth's Rotation . Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-521-46194-4 .

- ↑ John FA Sawyer, Joshua 10: 12-14 and the solar eclipse of September 30, 1131 BC Palestine Exploration Quarterly 1972.

- ^ Ristoro d'Arezzo: Delle composizione del mondo , book 1, chap. 16 (1282), cit. after FR Stephenson: Historical Eclipses and Earth's Rotation , Cambridge University Press: New York 1997, p. 398

- ↑ For the calculated duration see also John FA Sawyer: Joshua 10: 12-14 and the solar eclipse of 30 September 1131 BC In: Palestine Exploration Quarterly 1972, p. 145.

- ^ BE Schaefer: Lunar visibility and the crucifixion , in: Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 31 (1990), pp. 53-67.

- ^ JP Pratt: Newton's date for the crucifixion [correspondence]. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society , 32 (1991), pp. 301-304.

- ↑ Colin J. Humphreys, WG Waddington: Dating the Crucifixion , Nature 306 (1983), pp. 743-746.

- ^ A b J. P. Pratt: Newton's Date for the Crucifixion . Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society 32/3 (1991), pp. 301-304. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1991QJRAS..32..301P .

- ↑ John Knight Fotheringham : On the smallest visible phase of the moon . Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 70, London 1910, pp. 527-531. - Ders .: Astronomical Evidence for the Date of the Crucifixion . Journal of Theological Studies 12, Oxford 1910, pp. 120-127. - Ders .: The Evidence of Astronomy and Technical Chronology for the Date of the Crucifixion . Journal of Theological Studies 35, Oxford 1934, pp. 146-162.

- ^ BE Schaefer: Lunar Visibility and the Crucifixion . In: Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society . 31, No. 1, 1990, pp. 53-67.