Unification of the Empire (Egypt)

| Unification of empires in hieroglyphics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predynastics |

Sema-schemau-mehu |

|||||

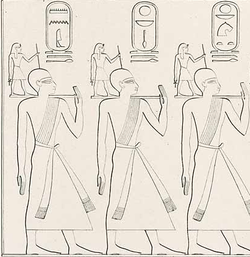

| The three unified empires Menes , Mentuhotep II and Ahmose I ( Ramesseum , west wall) | ||||||

The first empire unification of Upper and Lower Egypt is mostly attributed to Menes , who was king around 2980 BC. Ruled. As the founder of the 1st dynasty in the early dynastic period , the assessment as the “first unifier” is unhistorical, as his predecessors saw themselves as rulers of Upper and Lower Egypt during the festival of unification . The designation of Schemau for "Upper Egypt" and Mehu for "Lower Egypt" was first documented under King Iri in the predynastic period.

iconography

Iconographically , the union is represented by the symbolic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt, the lotus and the papyrus , which are either wrapped around the windpipe or artery of an animal by Horus and Seth or by two Hapi figures . Other symbols of the association are bees and rushes as well as the gods Wadjet and Nechbet in the royal titular.

Unification of the empire

Period

With regard to the first unification of the two regions of Upper and Lower Egypt, reference was made to the time of Menes and Narmer , although it is not yet clear whether Menes is Narmer or Aha . The main source here is the Narmer palette , whereby some Egyptologists refer to the iconographic motif of "beating the enemy" used there in Lower Egypt and Narmer as the "conqueror of the enemy" is attributed to Upper Egypt. However, it remains unclear whether Narmer achieved a victory over all of Lower Egypt or just some regions. In addition, it is not clear whether Menes was the first unification of the empire or whether similar unions had already existed before. In addition, it is a matter of dispute how the borders ran at that time, which is why an exact allocation of the earlier parts of the country is not possible.

Wolfgang Helck , for example, uses archaeological finds in connection with the Escort of Horus to point out the possibility that documented exchange deliveries speak for the existence of a centrally ruled Egypt even before Narmer. Vessel inscriptions and clay carvings from Girga , Tarchan and Abydos are among the earliest evidence of the exchange of goods. Due to a lack of text sources, it cannot be decided whether the exchange was about trade relationships or ritual basics. Most of these vessel inscriptions are made of black ink and were subsequently burned in. Jochem Kahl sees the exchange objects closely related to the escort of Horus as symbolic gifts of the king, which were in connection with the rewards of high dignitaries in cult ceremonies . Two plaques found in Naqada suggest the association with festive activities during this ceremony. So the king stepped on the so-called Menestäfelchen in front of his palace to examine the deliveries made.

Wolfgang Helck cites the first appearance of recorded annals as the reason for earlier assumptions of Menes as the “first unifier” . In addition, the question of whether the unification of the empire was brought about peacefully or forcibly and whether there was “the unification of the empire” at all was discussed in Egyptology. The contents of the ancient Egyptian sources, which refer to a larger period in which numerous unions took place, speak against a one-off act of unification. In this respect, there was no central, one-off unification of the empire. Rather, the two parts of the country grew together over several centuries and several stages up to the Middle Kingdom , which were characterized by interim separations.

Implementation of the unification of the empires

Recent studies show that the unification of the empire was not accomplished through military conquests, although in individual cases armed conflicts did occur. For example, the connection between the total number of prisoners under Narmer in connection with a military conflict, which was often established in the past, can no longer be maintained. An army size of more than 100,000 people can not be proven in the Old Kingdom , which is probably why Narmer counted all residents of a region and then referred to them as "rebels" ("sbj.w") using the determinative ; there was also no division between men and women. On the "club head of the Narmer" the overall peaceful takeover of a larger region is described, which at the same time has the character of a census .

What was striking in the early phase of the unification of the empires was the number of “rebels” counted in relation to the cattle herds mentioned at the same time. For the most part, this ratio was around 1: 3 during the Predynastics and the Old Kingdom; in the New Kingdom it increased to 1:10. The figures recorded under Snofru are one of the few exceptions. The figures mentioned were mostly based on lists of tribute payments that originate from regions outside the actual core territory. The change in the numerical ratio gives rise to the assumption that in the early phase of the unification of the empire larger areas were gradually added to the actual dominion area. In this context, a change in lifestyle in the course of settling down is seen as an additional option.

See also

literature

- Susanne Bickel : The link between the state and the world . In: Reinhard Gregor Kratz: Images of Gods, Images of God, Images of the World. Vol. 1: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, Asia Minor, Syria, Palestine. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2006, ISBN 3-16-148673-0 , pp. 79-102.

- Wolfgang Helck : Economic history of ancient Egypt in the 3rd and 2nd millennium BC. Brill, Leiden 1975, ISBN 90-04-04269-5 , pp. 21–32.

- Jochem Kahl : Upper and Lower Egypt: A dualistic construction and its beginnings. In: Rainer Albertz : Spaces and Boundaries: Topological Concepts in the Ancient Cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean. Utz, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-8316-0699-4 ( online ).

- Christiana E. Köhler : The State of Research on Late Predynastic Egypt: New Evidence for the Development of the Pharaonic State? In: Göttinger Miszellen 147, Göttingen 1995, pp. 79-92.

- Bruno Sandkühler: Lotus and Papyrus. The breath of Egypt. Verlag am Goetheanum, Dornach 2017, ISBN 978-3-7235-1575-4 .

- Thomas von der Way : The excavations in Buto and the unification of the empire. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) No. 47, 1991, pp. 419-424.

Individual evidence

- ^ J. Kahl: Upper and Lower Egypt: A dualistic construction and its beginnings. Munich 2007, p. 12.

- ^ J. Kahl: Upper and Lower Egypt: A dualistic construction and its beginnings. Munich 2007, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. illustrated new edition, Routledge, London / New York 2001, ISBN 9780415260114 , pp. 57–59.

- ^ J. Kahl: Upper and Lower Egypt: A dualistic construction and its beginnings . P. 13.

- ^ Christiana E. Köhler: The State of Research on Late Predynastic Egypt: New Evidence for the Development of the Pharaonic State? Göttingen 1995, pp. 86-87.