Narmer

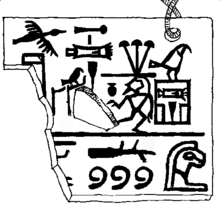

| Name of Narmer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Representation of the Narmer ( palette of the Narmer )

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Horus name |

nˁr catfish

Nˁr-mr (Nˁr-mḥr) Fearsome catfish

Nˁr-mr-ṯ3j (Nˁr-mḥr-ṯ3j) Narmer, "the male" |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Narmer (also Nar ; actually Hor-nar-mer , Hor-nar-meher , Hor-nar ) ruled around 3000 BC. According to some Egyptologists, he was the last ancient Egyptian king ( pharaoh ) of the 0th dynasty , according to another doctrine he was already the first ruler of the 1st dynasty . He is one of the Egyptian kings who is documented more often in early contemporary sources and is perhaps to be equated with Menes .

Although particularly important finds are known from Narmer, including his “ pompous palette ” and his club head, little is known about the origin and identity of this important ruler, which is why many controversial theses have been put forward about him. But there is no question that Narmer promoted the culture and well-being of the country in the long term and paved the way for a glamorous empire.

Surname

The Horus name of Narmer several variants have survived. While only the “Nar-Wels” appears in the Serech , especially on vessels , the name is written in full on clay seals or even extended by the epithet “Tjai” (in German “the male”). Although Narmer's name has been known for a long time, it has not yet been translated satisfactorily. The phonetics of the Nar catfish, the ruler's heraldic animal, causes difficulties for linguists and Egyptologists alike. What the catfish means symbolically is completely unknown.

The common reading as "Angry Catfish" or "Fearful Catfish" is widely accepted, although there have been suggestions for different readings. In this context, Hartwig Altenmüller explains the rebus principle , which has mostly been used to date , from which the common reading resulted from the addition of the terms “nar” (“catfish”) and “mer” (“chisel”) . Altenmüller names an alternative reading of “sab” instead of “nar” and refers to interim doubts from other Egyptologists regarding the previous translation.

From a grave near Tarchan (grave 1100) comes a vessel that has an unusual variant of Narmer's name. A sign can be seen under the catfish in Serech, which, according to the Egyptologist Wolfgang Helck, is either Gardiner sign U6

|

identity

Narmer may have been married to Princess Neithotep . However, the family assignment of these nobles is controversial, because she could also have been the wife of King Aha . It is similar with a lady named Benerib (in German "With a friendly heart"). She is more likely to have been Narmer's daughter and Ahaz's wife. In this case Narmer's wife has not yet been identified. The heir to the throne, Hor-aha, is regarded as a son of Narmer.

It is controversial who Narmer's predecessor was. Part of Egyptology prefers King Ka , while the other part regards King Scorpio II as the predecessor.

Domination

Domestic politics

Earlier interpretations of the artefacts found, especially the club pommel and the pompous palette, conveyed a rough picture of a possible further unification of the empire under Narmer, which was shaped by military campaigns . Decisive for the earlier interpretations was the depiction of the king killing an opponent with his ornate club, as well as the repetitive images of destroyed bastions and slaughtered enemies. But precisely because these representations are repeated in their style and their content and can be demonstrably traced back to Narmer's time, Toby Wilkinson and Kathryn Bard ask themselves whether this is really a historical event or not a symbolic wish of the Ruler is held as sole ruler after legitimizing his claims to power. The question is reinforced by the fact that the motif of “ slaying the enemy ” in later dynasties was also used for completely different ethnic groups (for example Nubians ) and for occasions.

Recent studies also show that the unification of the empire was not accomplished through military conquests, although armed conflicts did occur in individual cases. For example, the connection between the total number of prisoners under Narmer in connection with a military conflict, which was often established in the past, can no longer be maintained. An army size of more than 100,000 people can not be proven in the Old Kingdom , which is probably why Narmer counted all residents of a region and then referred to them as "rebels" (sbj.w) using the determinative ; there was also no division between men and women. On the “club head of the Narmer” the generally peaceful takeover or union with a larger region is described, which at the same time has the character of a census .

Wolfgang Helck , for example, uses archaeological finds in connection with the Escort of Horus to point out the possibility that documented exchange deliveries speak for the existence of a centrally ruled Egypt even before Narmer. Vessel inscriptions and clay carvings from Girga , Tarchan and Abydos prove a lively exchange of various goods and goods between Upper and Lower Egypt. They are among the earliest evidence of written documents about the exchange of goods. This fact allows the assumption that there was already a practiced, peaceful country policy between North and South before Narmer, especially since an exchange of goods only works through a central administration. Due to a lack of text sources, it cannot be decided whether the exchange was about trade relationships or ritual basics. Most of these vessel inscriptions are made of black ink and were subsequently burned in.

Foreign policy

Under Narmer's rule there were contacts to countries outside the Egyptian core empire, which can be proven by the ruler's name on various artifacts. In the southwest of present-day Israel ( Tel Arad , En Besor , Rafiah , Tel Erani ) one found vessels with Narmer's name. This may even indicate campaigns in this area. On the Sinai, his name was found carved into a rock. There is also an ivory plaque from Abydos depicting an Asian man kneeling or stumbling. The badge is particularly early evidence of contact between Egyptians and Asians. Fittingly, there were vessels at Hierakonpolis and Qustul , the decor and lettering of which indicate brisk trade between Nubia and Egypt. Other objects, on the other hand, suggest a conflict with Libya , for example an ivory cylinder from Narmer's grave. On it is the Nar catfish (main element of Narmer's name), who is holding a long baton in his arms. The baton extends over three registers, in which tied men with long, conical beards crouch. The beards identify the men as Libyans.

Ancient Egyptian mythology

Under Narmer the gods Horus , Seth , Mafdet , Reput , Bat , Neith , Mehit , Ptah , Apis and Min are quite well documented. Especially the goddesses Bat and Neith were worshiped. From Min there were large statues made of sandstone near Koptos , which can be assigned due to their unambiguous posture and probably come from Narmer's era.

Equation with Menes

There is still controversial debate in Egyptology as to whether Narmer and the name of King Menes can be equated. A comparison of the monuments shows that the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt was already celebrated several times by Narmer's predecessors, since only the "defeat of Lower Egypt" enabled rule over both parts of the country. However, this overall rule was only linked to the king who defeated "Lower Egypt".

The fact that Narmer is depicted on the pompous palette with the white crown of the south ( Ta-seti ) and the red crown of the north speaks in favor of equating Narmer with Menes . - Against this argument speaks the fact that Narmer had only successfully completed a military offensive against Lower Egypt, of course he was presented as the victor with the royal insignia of his defeated opponent. But that does not mean that he must have already been the generally accepted sole ruler of Egypt.

One of the oldest written representations of the hieroglyph Mn (Men - Gardiner symbol Y5 ) is engraved on an ivory tablet from the tomb of Aha near Abydos, directly opposite the royal Serech des Aha. It is located within a tent-shaped, triple decorative frame, together with an old form of the Nebti name . The tent-like structure is a pavilion that was built for commemorations at the death of a ruler. If the Mn symbol should actually represent the name "Meni", it can only mean Narmer, because Aha was still alive according to the label when the pavilion was visited. This is countered by the fact that the name of King Aha should actually also have appeared as a side name, because the ivory tablet was only put into the grave after Ahaz died. In addition, it is not certain that the word men stands for a personal name, it could just as well be the name of the building.

On a club head from Hierakonpolis , Narmer is shown performing a ceremony which Percy E. Newberry interprets as a wedding ceremony. According to him, Narmer is married to the Lower Egyptian hereditary princess Neithhotep . This marriage would have confirmed Narmer as ruler of Upper and Lower Egypt. Against this interpretation, the fact that the only definitely female person on the pompom is not named, so it does not necessarily have to be Princess Neithhotep, especially since Narmer had several wives. Toby Wilkinson and Nicolas Grimal identify the female figure , wrapped in robes and crouching in a covered litter, not as a princess, but as a repit , who was first documented as an independent deity in the Middle Kingdom . Wilkinson refers in its descriptions of the "répit" refers to an only fragmentarily obtained reading "[.] [.] P t" and establishes a connection to the basis of the name components reput - shrine forth.

On the Cairo stone , Djer , the third king of Egypt, is known as "Iteti". In conclusion, Teti I must mean King Aha as the second name in the king lists, which is why the name “Meni” only remains for Narmer. - Against this is the fact that entries about the end of Aha's reign and the beginning of Jer's reign provide evidence of a short-term reign of another king. This circumstance precludes equating “Teti” with Hor Aha and possibly proves another independent king.

Several clay seals come from the grave of the ancient Egyptian king ( Pharaoh ) Den in Abydos, on which four early rulers are listed by their Horus names : Narmer, Aha, Djer and Wadji . The list ends with the title and name of Queen Mother Meritneith. The fact that the list of kings begins with Narmer could indicate that he was regarded as the first legitimate ruler of the 1st Dynasty . Further seal impressions from Abydos name Narmer and the seven following, also documented at the time, rulers of the 1st Dynasty up to Qaa. This time Meritneith is missing. On this seal too, Narmer is the first ruler.

Representations

In 1897/98 the Egyptologist James Edward Quibell came across important pieces from early Egyptian history in Hierakonpolis . There, in one of the oldest temples in the country, he found a number of votive offerings , including magnificent palettes, including those of King Narmer, and club heads. Numerous ivory cylinders, clay seals and vessels also bear Narmer's name.

The palette of the Narmer

The most famous representation is the “pomp” or “make-up” or “Narmer palette”, which was donated as a dedication to the Upper Egyptian Temple of Horus in Hierakonpolis. It is made of polished slate and is about 64 centimeters tall. The palette is decorated on both sides and almost completely undamaged. King Narmer is depicted on both sides: once with the red crown of Lower Egypt , another time with the white crown of Upper Egypt . Narmer always wears a magnificent robe made of linen in combination with an apron made of panther skin and a crocodile tail attached to the belt.

Narmer is portrayed in the traditional slaying of an enemy by means of the two hieroglyphs on top of one another

|

According to Thomas Schneider , the gold rosette has the sound value neb ("Lord") in Narmer's time , which, along with nesu, served as a title for kings of that time. In the further course of ancient Egyptian history, the gold rosette was also used for the goddess Seschat , which is why Schneider considers it possible that originally her properties of the panther skin or the panther cat are represented. If this assumption is correct, a reading results as nebit (“panther cat”). This assumption is supported by the god "Neb-kau" named in the text of the pyramid 426. Alternatively, Schneider also considers reading as a “ refuge stick” (“nebit”), which could express a sacred founding ritual. Othmar Keel also sees Narmer's action as a sacred ritual , which Narmer performs barefoot on consecrated ground, while the sandal wearer with a water-filled vessel is probably ready for later “cleaning”.

The Victory Celebration of Narmers can also be seen. Accompanied by the escort of Horus , shown as a progressing procession made up of standard bearers, he looks at the killed enemies. This time he is accompanied by a sandal carrier. In front of him is the oldest image of a Tjet . Interesting is the depiction of two " snake neck panthers " in the window below, representing Narmer as ruler of both parts of Egypt as part of the unification festival. In the bottom window you can see a man and a damaged bastion , both of which are overrun by a bull. The bull represents the king. A similar scene can be found on a fragment of the so-called “ bull palette ”.

The club head

This find also comes from Hierakonpolis and shows Narmer celebrating the Sed festival . He sits in a pavilion and wears a skin-tight robe and the Red Crown of Lower Egypt. At this point, Narmer appears to have already taken both parts of Egypt. Before him, the divine is reput - shrine built. Some Egyptologists see the representation of a goddess or the princess Neithotep in the "Reput cult image" , which led them to interpret this scene as a wedding ceremony . Werner Kaiser and Günter Dreyer referred in this context to the fact that it was not a goddess, but a ritual portrait .

The vulture goddess Nechbet hovers above the royal pavilion , and several prisoners and captured cattle are shown to the ruler. Furthermore, the temple of Buto can be seen on the club head , recognizable by the image of a crane on an altar, the pedestal of which is adorned with a standing jug at the very front. There is also a domain whose name is spelled with a cow and her calf.

The baboon figure

In the Egyptian Museum Berlin there is a figure made of calcite - alabaster in the shape of a baboon , which probably represents Wer-wadet . The real name of Narmer is engraved on the front of the base and next to it the figure of a ram appears several times . Here the Egyptologists are unsure whether it is an epithet of Narmer or a particularly early depiction of the god Khnum .

The Nag el-Hamdulab rock art

At Nag el-Hamdulab , north of Aswan , there is a rock painting discovered at the end of the 19th century and rediscovered in 2008, which shows a representation of a king of the late predynastic or early dynastic period. Since the picture does not have any hieroglyphic texts, it is unclear which king was actually depicted here. However, both compositionally and stylistically, the scene shows very strong parallels to the club head of Scorpio II as well as to the club head and the palette of Narmer, which makes it plausible that one of these two rulers is depicted. The rock painting shows a male person looking to the left, holding a staff and identified as a king by a tall white crown and a pointed beard. Behind the ruler stands a frond bearer and in front of him a dog and two standard bearers. This royal representation is framed by five boats.

dig

Flinders Petrie located Narmer's grave in structure B10, which he excavated in the Umm el-Qaab necropolis near Abydos. Today, B10 is regarded as part of the grave of Hor-Aha , whereas the actual grave of Narmer is believed to be in the two pits B 17/18. The grave consists of two mud brick-built chambers with an area of 10 × 3 m² each.

These grave rooms were not built separately, but lie directly next to each other and are only separated by a wall. In the grave some unrolled seals of Narmer, ivory objects with his name and the oldest annual tablets of an Egyptian ruler were found. Other objects by Narmer from Umm el-Qaab are fragments of alabaster vases with his name in raised reliefs.

literature

- Günter Dreyer : A vessel with an incised mark from Narmer. In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department (MDAIK) Volume 55, von Zabern, Mainz 1999, ISSN 0342-1279 , pp. 1–6.

- Walter Bryan Emery : Egypt - History and Culture of the Early Period . Fourier, Wiesbaden 1964, ISBN 0-415-18633-1 .

- Nicolas Christophe Grimal : A history of Ancient Egypt . Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford et al. 1994, pp. 36-39.

- Jochem Kahl : The system of the Egyptian hieroglyphic writing in the 0–3. Dynasty. In: Göttinger Orientforschungen (GOF) . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-447-03499-8 , pp. 79-86.

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs . Artemis & Winkler, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7608-1102-7 .

- Siegfried Schott : Ancient Egyptian festival dates . Verlag der Akademie der Wissenschaften und der Literatur, Mainz et al. 1950, pp. 63–64.

- Toby AH Wilkinson : Early Dynastic Egypt . Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18633-1 .

Web links

- Narmers biography on: nefershapiland.de ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- Digital Egypt for Universities: Namer . (English) On: digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- The Ancient Egypt Site: Horus Narmer . (English) On: ancient-egypt.org ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- Francesco Raffaele: Horus Narmer . (English) On: xoomer.virgilio.it ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- The Bull Palette . (English) - The bull palette (assignment uncertain) On: reshafim.org.il ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- Ilona Regulski: Database of Early Dynastic inscriptions . (English) On: www4.ivv1.uni-muenster.de ; last accessed on June 27, 2017.

- Thomas C. Heagy: The Narmer Catalog . (English) On: narmer.org ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- Stan Hendrickx: Narmer Palette Bibliography . (English) On: narmer.org ; last accessed on October 20, 2017.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Joachim Friedrich Quack: On the sound value of Gardiner Sign-List U 23. In: Lingua Aegyptia No. 11, 2003, pp. 113–116.

- ↑ a b Rainer Hannig: The language of the pharaohs. (2800–950 BC) Part 1: Large concise dictionary, Egyptian - German. von Zabern, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , p. 1253.

- ^ Nicolas Christophe Grimal: A history of Ancient Egypt. Oxford et al. 1994, pp. 36-39.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: History of Ancient Egypt . Brill, Leiden 1981, ISBN 90-04-06497-4 , p. 22.

- ^ Andrew Godron, In: Annales du service des antiquités de l'Égypte (ASAE) Volume 49, Edition 1976, pp. 217 ff. And p. 547 .; Vikentieff, In: Journal of Egyptian Archeology (JEA) No. 17, p. 67 ff.

- ↑ a b Hartwig Altenmüller : Introduction to hieroglyphic writing. Buske, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-87548-373-1 , p. 59.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog: Inscription 0109 . On: narmer.org ; last accessed on July 4, 2017.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck: Investigations on the Thinite Age , Otto Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 978-3447026772 , p. 90 ( online )

- ^ Edwin CM van den Brink: The Pottery-Incised Serekh-Signs of Dynasties 0-1. Part 11: Fragments and Additional Complete Vessels. in Archéo-Nil , Volume 11, 2001 ( online )

- ↑ Walter Bryan Emery: Egypt - History and Culture of the Early Period . Wiesbaden 1964, pp. 38-44.

- ^ Günter Dreyer: Umm el-Qaab: Follow-up examinations in the early royal cemetery. 3rd / 4th Preliminary report. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 46, Mainz 1990, p. 71.

- ^ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 53, 66.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony : Inscriptions of the early Egyptian times. Volume III, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1963, pp. 1061ff.

- ↑ K. Bard: The emergence of an Egyptian state. In: Ian Shaw: The Oxford history of Ancient Egypt. Oxford-University Press, 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Christiana E. Köhler: The State of Research on Late Predynastic Egypt: New Evidence for the Development of the Pharaonic State? . In: Göttinger Miszellen (GM) Volume 147, Göttingen 1995, pp. 86-87.

- ↑ Jürgen Kraus: The Demography of Ancient Egypt: A Phenomenology Using Ancient Egyptian Sources . Göttingen 2004, p. 164.

- ↑ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt London 1999, pp. 57-59.

- ^ Günter Dreyer, Ulrich Hartung, Thomas Hikade, E. Christiana Köhler, Vera Müller, Frauke Pumpenmeier: Umm el-Qaab. Follow-up examinations in the early Königsfriedhof 9./10. Preliminary report In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 54, Mainz 1998, p. 139, Fig. 29.

- ↑ Jochem Kahl: The system of the Egyptian hieroglyphic writing in the 0. – 3. Dynasty. In: Göttingen Orient Research. Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 79-86.

- ↑ Wolfgang Helck : Investigations on the Thinite Age (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen. [ÄA] Volume 45). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-447-02677-4 , p. 132.

- ↑ Pierre Tallet, Damien Laisnay: Iry-Hor et Narmer au Sud-Sinaï (Ouadi 'Ameyra), un complément à la chronologie des expéditios minière égyptiene. In: Bulletin de l'Institut français d'archéologie Orientale. (BIFAO) 112, 2012, pp. 387-389, Fig. 10 ( online ).

- ^ T. Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 67-70.

- ↑ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, pp. 162-163.

- ↑ Walter Bryan Emery: Egypt - History and Culture of the Early Period . Wiesbaden 1964, pp. 134-137.

- ↑ Thomas C. Heagy: Who was Menes? In: Archeo-Nile. No. 24, 2014, pp. 59-92.

- ↑ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt . Routledge, London 2000, ISBN 0-415-18633-1 , p. 268 ff.

- ↑ Walter Bryan Emery: Egypt - History and Culture of the Early Period . Wiesbaden 1964, pp. 28-33.

- ^ Günter Dreyer: A seal of the early royal necropolis of Abydos. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 43, Mainz 1987, pp. 33-45.

- ↑ Werner Kaiser: On the seal with the early royal names of Umm el-Qaab. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 43, Mainz 1987, pp. 115-121.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog: Inscription 1553 . On: narmer.org ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog: Inscription 4048 . On: narmer.org ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- ^ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt. London 1999, p. 191.

- ↑ The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts of the paper impressions and photographs of the Berlin Museum. PJ1553.A1 1908 cop3, p. 426 From : lib.uchicago.edu , accessed September 6, 2014.

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: The character "Rosette" and the goddess Seschat . In: Studies on ancient Egyptian culture (SAK) No. 24, 1997, pp. 241-267.

- ↑ Othmar Keel: The world of ancient oriental symbols and the Old Testament . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, ISBN 3-525-53638-0 , p. 271.

- ^ Nicolas Christophe Grimal: A history of Ancient Egypt. Oxford et al. 1994, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Bull palette, Louvre E 11255 (English) on xoomer.virgilio.it ; accessed on September 6, 2014.

- ^ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt . London 1999, pp. 68-69.

- ^ The Narmer Catalog: Inscription 0125 . On: narmer.org ; last accessed on June 25, 2017.

- ^ E. Schott, In: Communications of the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 50, Mainz 1994, p. 224ff.

- ^ Stan Hendrickx, Maria Carmela Gatto: A rediscovered Late Predynastic-Early Dynastic royal scene from Gharb Aswan (Upper Egypt). In: Sahara. Volume 20, 2009, pp. 147-150 ( online ).

- ↑ Flinders Petrie : The royal tombs of the earliest dynasties: 1901. Part II (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Volume 21). Egypt Exploration Fund et al., London 1901 ( digitization ), p. 7.

- ^ Werner Kaiser, Günter Dreyer: Umm el-Qaab. Follow-up examinations in the early royal cemetery. 2. Preliminary report. In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. Volume 38, Mainz 1982, pp. 211-269.

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie: The royal tombs of the earliest dynasties: 1901. Part II. London 1901, Plate XIII, pp. 91-93.

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie: The royal tombs of the earliest dynasties: 1901. Part II. London 1901, Plate II, pp. 4-5.

- ^ WM Flinders Petrie: The royal tombs of the first dynasty: 1900. Part I (= Memoir of the Egypt Exploration Fund. Volume 18). Egypt Exploration Fund et al., London 1900, ( digitization ), panel IV, p. 2; WM Flinders Petrie, Francis Llewellyn Griffith: The royal tombs of the first dynastys, Part II. London 1901, Plate II, 3, 5.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| unsure |

King of Egypt 0th Dynasty (end) |

Aha |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Narmer |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Nar; Hor-nar-mer; Hor-nar-meher; Hor-nar |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | last ancient Egyptian king of the 0th Dynasty |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 30th century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 30th century BC Chr. |