Scorpio II

| Names of Scorpio II. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Scorpion II. In portrait

(detail from the club head of Scorpion II.) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proper name |

Wḥˁ? ( Srq ?) Scorpio |

|||||||||||||||||||||||

Scorpio II was an ancient Egyptian ruler ( Pharaoh ) of the predynastic period ( 0th Dynasty ), who lived around 3100 BC. Ruled. Egyptologists do not rule out that Scorpio II was one of those kings who were able to secure a temporary regional union .

However, it remains unclear which areas were possibly united by Scorpio II. In addition, the regions of Upper and Lower Egypt were distributed differently in the predynastic period, which is why a reliable statement about the areas ruled by the early kings cannot be made. Only a few artifacts and written documents have survived from Scorpio II himself . Scorpio's exact chronological position and duration of reign remains uncertain due to the location.

Name, identity and time allocation

About the name

Scorpio's name is introduced on its club head by a six-pointed gold rosette, the symbolism and origin of which is the subject of intensive research and was initially used as a general coat of arms for “king” in the predynastic period. Ludwig David Morenz therefore interprets the gold rosette as a contemporary counterpart to the better known Serech . Toby Wilkinson also reads the gold rosette as a symbol for “king”. According to Thomas Schneider , the gold rosette in Scorpio's time had the sound value neb ("Lord"), which, in addition to "nesu", served as a title for kings of that time. In the further course of ancient Egyptian history, the gold rosette was used as a coat of arms for the goddess Seschat .

The reading and interpretation of Scorpio's name is associated with difficulties, since the translation of the Scorpio coat of arms at the time of Scorpio II can only be speculated for lack of further evidence. The ruler is therefore simply called “King Scorpio II” in general. Some Egyptologists associate the meaning of Scorpio's heraldic animal with the goddess Selket . Whose name is however only since the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom certainly witnessed and with "Selket / Serqet" transliterated with Srq.t transcribed . In this context, Jan Assmann refers to the multi-layered interpretation possibilities of a depicted animal. On the one hand, the Scorpio can be directly meant or, on the other hand, characterize its typical traits as a determinative , whereby without additional information it remains unclear whether there is a reference to a single property or whether all the behavior of a Scorpio is associated with the name.

In Egyptology it is also disputed whether Scorpio's name is actually already recorded as Horus name . Dietrich Wildung reads the inscriptions on the clay pots from Minschat Abu Omar as Serech with the name "Horus Scorpio", referring to the additional notes "Servant of Horus Scorpio". In addition, Wildung interprets the image of a crouched falcon as a symbol of the name of Horus and the deity Horus , which is located as a character in the upper area of the serech.

Identity and time allocation

In Egyptology , the existence of a ruler "Scorpio" is controversial. Neither the predecessor nor the successor of Scorpio II can be proven satisfactorily so far. Scorpio's name is interpreted by some Egyptologists in connection with the gold rosette as an epithet of King Narmer , since Narmer already has a permanent serechname. The art and processing style in the relief of the club head of Scorpio also shows a striking resemblance to the decoration of the pomp of Narmer.

Günter Dreyer and Werner Kaiser see him as the successor to the Ka and the predecessor of the Narmer . Jochem Kahl suspects based on the location of a divided Upper Egypt, in the southwestern region of which Scorpio II ruled, while Narmer exercised his reign in northern Upper Egypt at the same time. Wolfgang Helck , on the other hand, puts four more king names between Scorpio II and Narmer due to an uncertain reading and assigns Scorpio II as the last king to a " Hierakonpolis dynasty", which was replaced by King Iri as the founder of the subsequent Thinite dynasty .

Toby Wilkinson, on the other hand, regards Scorpio II as an "anti-king" of Narmer and King Ka and suspects, alongside Renée Friedman and Bruce Trigger , that Scorpio II ruled in Hierakonpolis, as the few finds focus on this region. The foundation of the club head at Hierakonpolis also underlines this assumption.

Reign

With regard to the predynastic division of territory, it can be ruled out with a high degree of probability that under Scorpio II a solid structure of Upper and Lower Egypt already existed and that Upper Egypt conquered Lower Egyptian regions as a whole, which resulted in a large-scale unification of the empire. The red crown of the north , which later symbolically marked Lower Egypt, still stood for the northern part of Upper Egypt in predynastic times, while the white crown was mainly worn by kings in southern Upper Egypt. In addition, the borders of Upper and Lower Egypt marked completely different areas in this epoch compared to the later course, which is why local kings, in addition to Narmer and Scorpio II, also asserted their claims to government.

The numerous victory standards in the decor of the club head allow the assumption that Scorpio II was able to bring part of the Egyptian territories under his control. Most of the acquired provinces were probably incorporated peacefully. It remains unclear whether Scorpio II actually had to use violence in all of the northern Rechit provinces. In Egyptology , the question is discussed in this context whether the Rechit owned fixed areas in the Nile Delta during Scorpio's time or whether the lapwing birds that were tied up generally stand for “prisoners, subjects” and “rebels”. The triumph over the "rebels" is shown on the club head: Lapwing birds are tied to Gau standards led by symbols of gods and totem animals .

One of the greatest economic and power factors will probably have been the irrigation systems, the development and use of which may have reached their first peak under Scorpio II. Michael Allan Hoffman refers to the dissertations of Karl Butzen on the increase of references to the creation and use of artificial irrigation systems; not just on the royal club head. Irrigation systems allowed an expanded cultivation of grain, vegetables and the rearing of livestock.

Possible tombs

The grave of Scorpio II has so far been considered undiscovered, but two previously unassigned graves are being considered as possible graves on a speculative basis. Günter Dreyer sees a possible burial site in the “B50” grave complex in the Abyden necropolis of Umm el-Qaab . Grave "B50" is an almost square chamber that is divided into four rooms by a cross-shaped mud brick wall . It is very close to the tombs of kings Ka and Aha.

Michael Allan Hoffman is also considering a grave in the Hierakonpolis necropolis (HK6, grave 1). This consists of adobe walls in a pit and was originally covered with wooden planks. The 3.5 m × 6.5 m large and 2.5 m deep grave could be traced back to the period between 3105 and 2945 BC. To be dated. There is no conclusive archaeological evidence of the assignment for any of the graves.

Finds and their evaluations

The club head of Scorpio II.

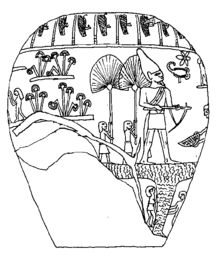

The best-known artifact, which is the only one that can be assigned to Scorpion II with absolute certainty, is the so-called "Club head of Scorpion II" from the "Treasure Depot" of Hierakonpolis , on which a king with the white crown of Upper Egypt can be recognized. A scorpion can be seen in front of his face , which is why it can be assumed that this was supposed to represent the name of the king. There is a six-pointed gold rosette directly above the scorpion. The head of the club is badly damaged on its surface, but most of the decoration in raised reliefs is very well preserved. The depicted scene is quite complex and provides valuable information about Scorpio II.

You can see Scorpio II holding a large pickaxe in his hands. He is accompanied by several loyal followers, of whom the one in front picks up the excavated earth or, according to another interpretation, throws out seeds. The rear loyalty, partly already lost in a broken edge, carries a huge grain sheaf. A parade of standard-bearers can be seen in an upper register , which precedes the king. Behind the king there are two frond-bearers that provide shade for the ruler. Behind it, in turn, two registers are shown, the upper one shows a priest in front of a Reput litter. The lower register shows papyrus thickets and a parade of dancing and singing women. The entire club-head scenery is the subject of numerous and controversial interpretations. Vladimir Vikintiev and Krzysztof Marek Ciałowicz consider a ceremony in connection with the Sedfest possible. Elise Jenny Baumgartel and Ludwig David Morenz, on the other hand, suspect a foundation festival in honor of the new temple complex in Nechen or Buto .

In the top window of the club relief, a line of gods' standards can be seen, on which the Rechit were hung. On the opposite side of the club head, fragmentary hunting bows are preserved. Deities like Seth , Min and Nemti are posted on the standards . Ciałowicz is convinced that he can prove a second king figure, this time with the red crown . At the point on the club relief where the lapwing and bow standards meet, another gold rosette has been preserved, along with a tiny remnant of a spiral typical of the “red crown of the north”. In this case, the club head of Scorpio II would be the earliest evidence of a king with a red crown, even before Narmer.

More finds

Locations |

In the eastern region of Sais , the fragment of a was Barken - slate palette found that in the time of kings and Scorpio II. Ka is (around 3100 BC..) Dates. Due to the detailed depiction of a tied lapwing, which is depicted on the boat deck with the determinative of a cage over the bow , the find is called the " lapwing palette ". The place of origin could not yet be determined. The club head and lapwing palette are also among the earliest documents on the Rechit.

Rock carvings near the second Nile cataract show Scorpio II during the evacuation of Nubian enemies, emblematically identified by hunting bows and ostrich feathers on its head. You can see a gigantic scorpion figure that strides over killed Nubians. The dead can be recognized by the fact that they are depicted upside down. In front of the scorpion stands a figure with a mustache and a ceremonial knife, which is interpreted as a king figure. The figure is holding a long rope to which captured Nubians are tied. The victory over the Nubians is also recorded on the head of the club: the hunting bows described above are the typical attribute of the Nubians at this time. Scorpio II expanded his empire to the south.

The assignment of a tablet from Abydos on which an enemy is slain by a scorpion turns out to be uncertain . Vessel inscriptions from Tarchan and Minschat Abu Omar are also known, most of which are attributed to Scorpio II. Günter Dreyer and Wolfgang Helck, however, reject these assumptions. More than a dozen ivory plaques show the temple (or cult place) of Buto , represented by an altar with a palace facade decoration on which a heron is enthroned. Other plaques show a scorpion, which is the symbol for "Gau" or "Garden"

|

At Nag el-Hamdulab , north of Aswan , there is a rock painting discovered at the end of the 19th century and rediscovered in 2008, which shows a representation of a king of the late predynastic or early dynastic period. Since the picture does not have any hieroglyphic texts, it is unclear which king was actually depicted here. However, both compositionally and stylistically, the scene shows very strong parallels to the club head of Scorpio II as well as to the club head and the palette of Narmer , which makes it plausible that one of these two rulers is depicted. The rock painting shows a male person looking to the left, holding a staff and identified as a king by a tall white crown and a pointed beard. Behind the ruler stands a frond bearer and in front of him a dog and two standard bearers. This royal representation is framed by five boats.

Modern reception

The British writer and Nobel Prize winner for literature William Golding published a short novel in 1971 with the title The Scorpion God (German: Der Skorpion-Gott , published together with two other short novels in 1974 under the title Der Sonderbotschafter ). In this he portrays life at the court of an early Egyptian ruler in an absurdly ironic way. The aging ruler (only called "Big House" - Pharaoh - in the novel) wants to renew his divine power by running a Sedfest , but falls in the process. In addition, the succession to the throne is not guaranteed. The king has a very attractive daughter who, according to Egyptian tradition, is supposed to marry her childhood brother, but who does not have the slightest desire to do so. The king's daughter now tries to seduce her father with an erotic dance, but this fails because he has long been impotent. The king then poisons himself and his court happily follows him into death. The only one who refuses is someone who is only called a "liar". Ironically, he is the only person who sees the events of the novel through the eyes of a rational person.

In the 2001 American film The Mummy Returns , the character of the Scorpion King , an early Egyptian warrior and later king, was introduced. In 2002 he received his own feature film, The Scorpion King , which was followed by three sequels as direct-to-DVD releases by 2015. Apart from his temporal location, this king has nothing in common with the historical ruler Scorpio and the Scorpion King films in particular are fantasy works that make use of historical and mythological set pieces from various cultures from the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

literature

- Rainer Hannig : Large Concise Dictionary of Egyptian-German (2800 - 950 BC) by Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 .

- Günter Dreyer : A seal of the early royal necropolis of Abydos . In: Communications from the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department. (MDAIK) No. 43. von Zabern, Mainz 1986, pp. 33-43.

- Günter Dreyer: Umm el-Qaab: Follow-up examinations in the early royal cemetery. 3rd / 4th Preliminary report . In: MDAIK No. 46. von Zabern, Mainz 1990, pp. 53-89.

- Ulrich Hartung : Umm el-Qaab, part 2: Imported ceramics from the U cemetery in Abydos (Umm el-Qaab) and the relationship between Egypt and the Middle East in the 4th millennium BC Chr. (= Archaeological Publications. [AV] Vol. 92). von Zabern, Mainz 2001, ISBN 3-8053-2784-6 .

- Wolfgang Helck : Investigations on the Thinite Age (= Ägyptologische Abhandlungen. (ÄA) Vol. 45). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1987, ISBN 3-447-02677-4 .

- Jochem Kahl: Upper and Lower Egypt: A dualistic construction and its beginnings. In: Rainer Albertz (Ed.): Spaces and Borders: Topological Concepts in the Ancient Cultures of the Eastern Mediterranean. Utz, Munich 2007, ISBN 3-8316-0699-4 ( online ).

- Werner Kaiser, Günter Dreyer: Umm el-Qaab: Follow-up examinations in the early royal cemetery. 2. Preliminary report. In: MDAIK No. 38. von Zabern, Mainz 1982, ISBN 3-8053-0552-4 .

- Peter Kaplony: Inscriptions of the early Egyptian period: Supplement. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1966, ISBN 3-447-00052-X .

- Ludwig David Morenz: Image letters and symbolic signs: The development of the writing of the high culture of ancient Egypt. (= Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 205). Friborg 2004, ISBN 3-7278-1486-1 .

- Thomas Schneider : Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 .

- Dietrich Wildung : Egypt in front of the pyramids - Munich excavations in Egypt. von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0523-0 .

- Krzysztof Marek Ciałowicz: La naissance d'un royaume: L'Egypte dès la période prédynastique à la fin de la Ière dynastie. Inst. Archeologii Uniw. Jagiellońskiego, Kraków 2001, ISBN 83-7188-483-4 .

- Michael Allen Hoffman: The predynastic of Hierakonpolis: an interim report. In: Egyptian Studies Association Publication. No. 1, Cairo University Herbarium, Giza 1982, ISBN 977-721-653-X .

- Gay Robins: The Art of Ancient Egypt. Harvard University Press, Cambridge 2008, ISBN 978-0-674-03065-7 .

- Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security. Routledge, London 1999, ISBN 0-415-18633-1 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security. London 1999, p. 195, fig. 6.

-

↑ The name of a female scorpion is Wehat / Selket:

; according to Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800 - 950 BC). von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , pp. 225 and 790.

- ↑ Uncertain reading according to Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Ägyptisch-Deutsch. P. 1281.

- ↑ In Egyptology the kings before the early dynastic period are generally titled with "kings of the 0th dynasty". Hermann A. Schlögl refers to the more precise expression “Protodynastic Kings”, which characterizes the 0th Dynasty; see: Hermann A. Schlögl: The old Egypt. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-406-48005-5 , p. 59.

- ↑ special character M86; see Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German. P. 1444, there, however, referred to as "flower".

- ^ Anton Moortgat: The gold rosette - a character? . In: Ancient Near Eastern Research. No. 21, Institute for Orient Research, Berlin 1994, pp. 359-371.

- ↑ a b Ludwig David Morenz: Image letters and symbolic signs . Pp. 151-154.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security. London 1999, p. 191.

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German. P. 455.

- ↑ Thomas Schneider: The character "Rosette" and the goddess Seschat. In: Studies on Ancient Egyptian Culture. No. 24. Buske, Hamburg 1997, ISSN 0340-2215 , pp. 241-267.

- ^ A b c Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security . London 1999, pp. 56-57.

- ^ Gay Robins: The Art of Ancient Egypt . P. 34.

- ↑ Christian Leitz u. a .: Lexicon of Egyptian Gods and Designations of Gods (LGG) Vol. 6 . Peeters, Leuven 2002, ISBN 90-429-1151-4 , pp. 439-440.

- ↑ Jan Assmann: Stone and Time: Man and Society in Ancient Egypt . Fink, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-7705-2681-3 , p. 91.

- ↑ a b Hermann Alexander Schlögl: The ancient Egypt. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-406-48005-5 , p. 61.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: Egypt before the pyramids . Fig. 36.

- ^ Bernadette Menu: Enseignes et porte-étendarts. In: Bulletin de l´Institut Francais d´Archéologie Orientale. No. 96, Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale, Cairo 1996, ISSN 0255-0962 , pp. 339-342.

- ↑ a b c d Thomas Schneider: Lexicon of the Pharaohs. Düsseldorf 2002, p. 276.

- ↑ a b Jochem Kahl: Upper and Lower Egypt: A dualistic construction and its beginnings . P. 16.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security. London 1999, p. 39.

- ^ Henri Asselberghs: Chaos en beheersing: Documents uit Aeneolithisch Egypte. In: Documenta et monumenta orientis antiqui. No. 8, Brill, Leiden 1961, pp. 336–337, plate 90, fig. 159.

- ↑ a b Jochem Kahl: Upper and Lower Egypt: A dualistic construction and its beginnings . Pp. 11-12.

- ↑ a b c d Krzysztof Marek Ciałowicz: La naissance d'un royaume . P. 97ff.

- ↑ Michael Allan Hoffman: Egypt before the pharaohs: The prehistoric foundations of Egyptian Civilization . Routledge and Kegan Paul, London 1980, ISBN 0-7100-0495-8 , pp. 312-326.

- ^ Michael Allan Hoffman: Before the Pharaohs: How Egypt Became the World's First Nation-State . In: The Sciences . New York Academy of Sciences, New York 1988, pp. 40-47.

- ↑ Michael Rice: Egypt's Making: The Origins of Ancient Egypt 5000 - 2000 BC . Routledge, London 1991, ISBN 0-415-06454-6 , ( online version )

- ↑ Elise Jenny Baumgärtel, Ludwig David Morenz: Scorpion and Rosette and the Fragment of the Large Hierakonpolis Macehead . In: Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprach und Altertumskunde No. 93. Akademie-Verlag Berlin 1998, pp. 9–13.

- ^ A b Günter Dreyer: Umm el-Qaab: Follow-up examinations in the early royal cemetery. 3rd / 4th Preliminary report . P. 70.

- ^ Toby AH Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security. London 1999, p. 194.

- ^ Special characters U 103 according to Petra Vomberg: List of special characters. In: Rainer Hannig: Large Concise Dictionary Egyptian-German: (2800 - 950 BC). von Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-1771-9 , p. 1448.

- ^ Henri Asselberghs: Chaos en beheersing: Documents uit Aeneolithisch Egypte. In: Documenta et monumenta orientis antiqui. No. 8, Brill, Leiden 1961, pp. 222-224.

- ↑ Winifred Needler: A Rock-drawing on Gebel Sheikh Suliman (near Wadi Halfa) showing a Scorpion and human figures . In: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt . American Research Center (Ed.), Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake 1967, ISSN 0065-9991 , pp. 87-91.

- ^ Günter Dreyer: Horus Crocodile: A Counter-King of Dynasty 0 . In: Renee Friedman, Barbara Adams: The Followers of Horus: Studies dedicated to Michael Allen Hoffman, 1949–1990 . Oxford 1992, ISBN 0-946897-44-1 , pp. 259-263.

- ^ Toby Wilkinson: Early Dynastic Egypt: Strategy, Society and Security . London 1999, p. 54.

- ↑ Peter Kaplony: The inscriptions of the early Egyptian times. Vol. 2 (= Egyptological treatises. Vol. 8, 2). Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1963, p. 1090.

- ^ Stan Hendrickx, Maria Carmela Gatto: A rediscovered Late Predynastic-Early Dynastic royal scene from Gharb Aswan (Upper Egypt). In: Sahara. Volume 20, 2009, pp. 147-150 ( online ).

- ↑ BOOK: William Golding, "The Scorpion God" . In: Ill-advised. December 26, 2005; last accessed on November 28, 2015.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| unsure |

King of Egypt 0th Dynasty |

unsure |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Scorpio II |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Egyptian king from the pre-dynastic period |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 31st century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 31st century BC Chr. |