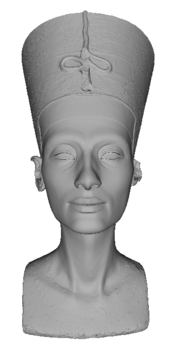

Bust of Nefertiti

| Bust of Nefertiti | |

|---|---|

|

|

| material | Limestone and stucco (painted), rock crystal inlay |

| Dimensions | H. 50 cm; |

| origin | Tell el Amarna , house P 47.2 (room 19) |

| time | New Kingdom , 18th Dynasty , Amarna period |

| place | Berlin , Egyptian Museum , inventory number 21300 |

The bust of Nefertiti , also known as the head of Nefertiti or just as (the) Nefertiti , is one of the most famous art treasures of ancient Egypt and is considered a masterpiece of sculpture from the Amarna period . It was built during the reign of King ( Pharaoh ) Akhenaten during the 18th Dynasty ( New Kingdom ) between 1353 and 1336 BC. Manufactured.

The bust of Queen Nefertiti was discovered on December 6, 1912 during excavations by the German Orient Society under the direction of Ludwig Borchardt in Tell el-Amarna in house P 47.2, the workshop of the head sculptor Thutmosis . It was brought to Germany in January 1913 with the approval of the Egyptian Antiquities Administration as part of the finding division . In 1920 the bust of Nefertiti was donated by James Simon to the Prussian state along with other objects that had previously been on permanent loan to the Egyptian Department of the Royal Prussian Art Collections . But to a public presentation built for the Egyptian collection of the National Museums in Berlin Museum on Berlin's Museum Island, it came only in 1924. Today it is owned by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation and is under the inventory number 21300 as the main attraction at the Egyptian Museum in Berlin , the has been housed again in the Neues Museum (north wing, north dome hall) on Berlin's Museum Island since October 16, 2009 . There are various statements about the value of the bust of Nefertiti. An insurance company estimated it at 390 million US dollars (300 million euros ) in 2009 , while on the other hand its value was also given as 400 million euros (around 520 million US dollars).

Discovery and History

prehistory

The story of Tell el-Amarna as an excavation site begins with the Jesuit priest Claude Sicard, who made copies of the border steles of the ancient city of Achet-Aton in November 1714 . He was followed by Napoléon Bonaparte's expedition , which found the “remains of an ancient city”. After further research and discoveries by John Gardner Wilkinson (1824), Karl Richard Lepsius (1842/1845), Flinders Petrie (1891/92), Norman de Garis Davies (1901) and visits by James Henry Breasted (1895), Ludwig Borchardt followed in 1907 .

France and England had research institutes in Egypt for several years. And so the German Academy of Sciences also called for German researchers to participate regularly in Egypt . However, there was no political, diplomatic or financial support for this. Kaiser Wilhelm II disliked the scientific lead that the two countries had as colonial powers in this field in Egypt: In future, historical objects should also be found in German museums, especially in Berlin , not only in the Louvre in Paris or the British Museum in London . Finally, in 1899, the position of a scientific attaché was created at the Imperial Consulate General in Cairo . The mandate of the incumbent was to inform the Berlin Academy of Sciences about all important events in the field of Egyptology . This post was filled by the architect and Egyptologist Ludwig Borchardt and in 1907 converted into a director position of the newly founded Imperial Institute for Egyptian Antiquity , the predecessor of today's Cairo Archaeological Institute (DAIK).

After the inventory of a Prussian expedition in 1842 under the direction of Karl Richard Lepsius, the first inspection of the area of Tell el-Amarna by Borchardt took place in 1907. To the south of the temple ruins were houses and workshops that the researchers found promising. Ludwig Borchardt was able to win the Berlin cotton merchant James Simon as financier of the following excavation campaigns, who had previously financed Borchardt's excavations at the pyramids of Abusir . From January to April 1911 the first major excavation campaign of the German Orient Society under Borchardt began in Amarna, for which Simon received the excavation concession on August 29th. The excavation was carried out by the German Orient Society, but a contract with Simon provided that he would pay 30,000 marks annually for the financing and that he would own all the finds from the German part of the campaign.

Find history and division

During the third excavation campaign in 1912/1913 (November 1912 to March 1913) by the German Orient Society in Tell el-Amarna, the bust of Nefertiti was found in the remains of a mud brick house in grid square P 47.2 in room 19 in the sculptor's studio Thutmose found. The evidence suggested that the bust must have stood on a wooden wall board, which had fallen to the floor when it fell apart. However, it remained largely intact and the rubble that had piled up over it preserved the bust. The find is listed in the find list under the number 748 with the brief description “painted bust of the queen”. Borchardt noted in his diary:

“[...] Then the colorful bust was lifted out and we had the most lively Egyptian work of art in our hands. It was almost complete, only the ears were bumped and the insert was missing in the left eye. "

In the same room a life-size, also painted and limestone bust of King Akhenaten (find no.1300) was found, but it was smashed. In contrast to the bust of Queen Nefertiti, it was evident here that the damage could not have been caused by falling.

At the time of Borchardt's work in Tell el-Amarna, Egypt was under British occupation and the then Egyptian Antiquities Service ( Service d'Antiquités Égyptiennes , also Département d'Antiquités ), today's Supreme Council of Antiquities , was under French management. The division of the finds from this excavation campaign took place on January 20, 1913 in accordance with the then applicable provisions "in equal shares" ( à moitié exacte ) for Egypt and the country carrying out the excavation. Borchardt had put the two parts together, which was the excavator's prerogative until 1914. Gaston Maspero , the director of the Antiquities Service, commissioned his colleague Gustave Lefebvre to organize the division of the finds. One part contained the bust of Nefertiti, the other, which Lefebvre finally selected for the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , the so-called folding altar of Cairo , a colored altarpiece showing the royal couple Akhenaten and Nefertiti with three of his children. According to Borchardt, the museum in Cairo did not have an altarpiece before, but wanted such a find, which was decisive for its assignment of the objects.

The reasons for Lefebvre's decision to award the part of the find with the "colorful queen" Borchardt and to choose the altarpiece for Egypt are unknown. The Egyptologist Rolf Krauss suggested that Borchardt was able to convince Lefebvre not to tear apart the found parts because of a closer examination. The former director of the Egyptian Museum Berlin , Dietrich Wildung , on the other hand, is of the opinion that Egyptologists at the time “tended to give more scientific importance to texts than to busts” . Borchardt wrote about Lefebvre in 1918 that, on the one hand, the division of the finds seemed too harsh to him, on the other hand, he also specialized in inscriptions and papyri and therefore did not recognize the value of the bust. Borchardt further reported that the result probably also played a role in his skill in negotiating the findings. However, critics such as Hawass describe this situation as a deception to disguise the value of the bust because it was only declared as a simple plaster model.

In 1914, Pierre Lacau succeeded Maspero and introduced stricter rules for the division of finds: all unique pieces should then be assigned to Egypt.

Stations of the bust

In 1913 James Simon received the export license for the bust from Egypt to Germany. It was brought to Berlin and initially set up in Simon's villa in the Berlin-Tiergarten district, where the Baden-Württemberg State Representation is now located . Here Kaiser Wilhelm II also looked at them several times. Since the division of the find, Borchardt has been very persistent of the opinion that the bust should not be presented to the public. On July 11, 1920, Simon converted the permanent loan of the objects from the Amarna excavation to the Egyptian department of the royal Prussian art collections into a gift to the Free State of Prussia . However, contrary to Borchardt's express request, the bust was shown for the first time in 1924 as part of the Berlin Tell el-Amarna exhibition on Berlin's Museum Island .

During the Second World War , the bust was initially stored in a box with the number 28 in the vault of the Reichsbank on Gendarmenmarkt in September 1939 and then moved to the flak bunker at the zoo in 1941 . In March 1945 the art and cultural assets were evacuated from the flak bunker into the tunnel of the Merkers salt mine in Thuringia . After Merkers was occupied by the US armed forces on April 4, 1945, the items were brought to the Reichsbank in Frankfurt 13 days later .

After the Second World War, the Americans set up an art collection point in Wiesbaden , the so-called Central Collecting Point . The bust of Nefertiti ended up in a box with the inscription The Colorful Queen from Frankfurt to Wiesbaden. The head of the art protection officers, Walter Farmer , prevented the bust from being exported to the United States . On May 12, 1946, on the initiative of Farmer, an exhibition of Berlin art objects was organized in the Wiesbaden State Museum , among which was the bust of Nefertiti. Der Spiegel reported in January 1947 that over 200,000 visitors had seen the exhibition. In 1948 the entire Berlin art depot was handed over to the fiduciary administration of the Hessian state government . The bust was on view in Wiesbaden for a total of ten years until 1956.

On June 22, 1956, the bust was transported back to West Berlin , where it was first exhibited in the museum's picture gallery in Dahlem . The bust of the queen came back to Berlin eleven years later and was part of the exhibition at the opening of the Egyptian Museum in Charlottenburg ( Eastern Stülerbau ) on October 10, 1967. Apart from the first CT examination, which was carried out in 1992 in the Charlottenburg Clinic of the Free University of Berlin near the museum, it remained there with the Egyptian collection until February 28, 2005. After that, the bust of Nefertiti was briefly part of the exhibition Hieroglyphs about Nefertiti in the Kulturforum Berlin , before it was temporarily shown again on August 13, 2005 in the Altes Museum on Museum Island. When the Neues Museum reopened on October 16, 2009, the bust of Nefertiti returned to its original location on Museum Island.

Queen Nefertiti

Nefertiti's origin is unknown and the views on this have changed over the past few years with the different locations and evaluations of the finds. Due to her name Neferet iiti (Nefertiti), which is translated as “The beautiful has come”, it was assumed, among other things, that Nefertiti was of non-Egyptian descent. For a time she was therefore equated with the Hurrian princess Taduhepa , a daughter of King Tušratta . Most historians assume, however, that Nefertiti was the daughter of Eje , the presumed brother of Queen Teje , and his first wife, and therefore also came from Achmim . Since Eje's second wife, Tij , is referred to as the queen's nurse in ancient Egyptian inscriptions , she can be excluded as the birth mother of Nefertiti; she was her stepmother. Another indication of their Egyptian origin is a sister named Mudnedjemet (also read as Mutbeneret / Mutbelet), mentioned in inscriptions , who held a high rank at the royal court and is considered to be the later wife of King ( Pharaoh ) Haremhab .

Nefertiti was the great royal wife of King Akhenaten , who raised the god Aton in the form of the solar disk to be the only god for the Egyptian royal family and ruled for 17 years. They had six daughters: Meritaton , Maketaton , Anchesenpaaton , Neferneferuaton , Neferneferure and Setepenre . Her name was written in a cartouche from Akhenaten's 5th year of reign together with the nickname “The beauties of Aton are beautiful” ( Nefer neferu Aton ) . At the beginning of 2012, scientists from the Flemish Catholic University of Leuven in Belgium discovered an inscription in a quarry near Achet-Aton that names both Nefertiti and Akhenaten in his 16th year of reign ("Year 16, 3rd month, day 15"). During Akhenaten's reign, the Deir Abu Hinnis quarry served as the main source of material for his new capital, Akhet-Aton. The five lines in hieratic script name Akhenaten's name and designate Nefertiti, whose name is written in a cartouche , in the third line: “Great royal wife, lover, mistress of the two countries, Neferneferuaton Nefertiti .” This discovery removes all previous hypotheses and speculation form the basis of the queen's whereabouts after Akhenaten's 12th and 14th year of reign. Nothing is known about the circumstances of Nefertiti's death or the age at which she died.

bust

The limestone bust does not have any hieroglyphic inscriptions. However, due to the characteristic crown, which Ludwig Borchardt himself described as a “wig”, it could be identified as a portrait of Queen Nefertiti in comparison with other depictions. The sculpture comes from the reign of Akhenaten and can therefore be assigned to the time of the 18th Dynasty ( New Kingdom ). During the Amarna period, the creation of the bust is attributed to the so-called "late Amarna phase", i.e. the last years of Akhenaten's reign, due to its design.

Dating

In spite of the chronological assignment, reliable dating and age determination, for example by means of C-14 analysis, is not possible because the bust has no or hardly any organic material. Generally today for the production of the bust 1340 BC. B.C., with the information differing over the years due to the different dates on the Egyptian chronology .

The paints used contain organic binders , but with the low mixing ratio of 100: 1, too few proportions for an examination to obtain a clear result. One possibility would be to use the tiny pieces of straw in the area of the crown for an analysis, whereby the removal of material would have to be minimal. As a dating option, Stefan Simon, materials scientist at the Rathgen Laboratory of the Staatliche Museen Berlin, considered subjecting the left eye to a more detailed examination to determine whether there were any wax residues there. On the other hand, Der Spiegel reported as early as 1997 that the Egyptologist Rolf Krauss came across an old wax sample while doing research in the magazine of the Egyptian Museum Berlin, which was probably taken from the bust by Friedrich Rathgen on the right pupil around 1920 and the bust was damaged in the process . A C-14 analysis was possible, which at the time of the investigation (1997) showed an age of the bust of 3347 years.

Workmanship and material

While Ludwig Borchardt noted a height of 47 cm in his diary, the height of the bust is now given as 50 cm. The sculpture weighs around 20 kg and consists of limestone covered with a layer of painted stucco . The iris of the right eye is an inlay made of rock crystal with a finely incised pupil, which is underlaid with black paint and fixed with beeswax. The white of the eyes is made up of the limestone used. The pupil of the left eye is missing and there is no evidence on the bust that it was ever or should be used.

Ludwig Borchardt had a chemical analysis of the colors used carried out and published the results of the investigation in 1924 in Portrait of Queen Nefertiti . The following components were found:

- Blue : colored glass powder ( frit ) with shares of copper oxide

- Skin color: fine lime powder with red lime ( iron oxide )

- Yellow: auripigment ( arsenic (III) sulfide )

- Green: colored glass powder with shares of copper and iron oxide

- Black: charcoal , with wax as a binder

- White: lime ( calcium carbonate )

The painting only took place after the surface modeling of the plaster of paris was completed. Microscopic photographs show that the five different layers of paint were applied one after the other: blue-white, white, yellow, blue and finally red.

Portrait of the queen

Nefertiti wearing the typical for them on numerous representations blue crown, often referred to as "helmet Crown", with golden headband to the horizontal, a colored ribbon ( diadem Reif ) is wound, converging centrally at the back and there appears to be from an insert of carnelian held surrounded by two papyrus umbels . The colors used here (yellow, red, blue, green) represent a diadem ring made of gold and precious stones, as found, for example, in Tutankhamun's grave treasure . Above the forehead was the royal uraeus snake , which itself is no longer preserved in detail, but its former existence can only be traced in its form through the gilded remains on the blue crown. A red band runs in the neck from the base of the crown, which rests on the upper back on the wide, polychrome neck collar ( Wesech ). Such ribbons lying in the neck are a typical attribute in art after Akhenaten's accession to the government. Compared to other ancient Egyptian busts, the shoulders are missing. The bust is only worked up to the point of the collarbones.

Ludwig Borchardt describes his first impression of the bust in his excavation diary with the following note:

“Colors as just applied. Excellent work. Describing is no use, looking at it. [...] Any further word is superfluous. "

The portrait of the queen shows even facial features with high cheekbones, a long and wrinkle-free neck and very narrow contours. Both halves of the face are symmetrical . The complexion is pinkish-brown and looks fresh. The full makeup of the face, the eyebrows, the eyelids rimmed with kohl, the not too full lips with a brownish shade of red make the image appear as if it had just been made up. In its individual design, the portrait not only corresponds to today's ideal of beauty, but it also gives the portrait of the queen a pronounced individuality and personality. Joyce Tyldesley summarizes the bust: [Thutmose] ... gave it a universal beauty that unfolds its effect across all borders of race and time.

Effect and fascination of the bust

The effect or fascination that the bust exerts on the viewer can be ascribed to various aspects: the almost perfect state of preservation with its bright colors and the vivid gaze of the right eye. The detailed work of the rock crystal pupil can also be found in the pair of statues of Prince Rahotep and his wife Nofret from the 4th Dynasty ( Old Kingdom ), for which this is world famous. The effects of the overall processing produce a lifelike representation and address the viewer directly despite idealizing features. Another point is that the bust combines both a passive and an active aspect: the head and neck seem to be pushed down by the heavy crown, the neck is directed forward. The tension, counteracting this and maintaining balance is emphasized by the long neck muscles that are emphasized. This is particularly evident at the back of the head below the base of the crown, at the transition from neck to head.

The Egyptologist Julia Samson captured the moment of the viewer in 1985 with the words:

"Everyone stops in amazement, spellbound by their appearance, some remain motionless for a long time, some come back not just once but again and again, as if they could hardly believe what they were seeing."

Missing left eye

The bust of Nefertiti never left Thutmose's workshop. After the bust was found, both the surrounding rubble and the rubble that had already been removed were searched. Small fragments of the ears were found during sifting, but the insert for the eye was not found. Borchardt wrote in his excavation diary: “It was not until much later that I saw that it was never there.” He later added that there were no traces of binding agent in the empty eye socket that would have indicated an inserted eye. In addition, no traces of processing were recognizable.

Opinions about the missing left eye of the bust are very different. As a rule, it is described that the left eye of the bust was probably never used and should demonstrate the work process on the object and thus serve as a model. On the one hand, it is said that the empty eye socket does not show any traces of an original attachment with the aid of an adhesive or processing, according to which the inlay must have been missing when the bust was made. Dorothea Arnold advocates assuming that the left eye was never present as long as microscopic examinations do not reveal any processing. Nicholas Reeves, however, states that earlier recordings showed visible traces of the same color body in the left, empty eye socket as in the right. According to Rolf Krauss, the eye was therefore present, but later fell out. According to Zahi Hawass, the bust was made with both eyes and the left was later destroyed. Joyce Tyldesley believes it is unlikely that "a single eye was torn out to attack the memory of the dead queen".

Stefan Simon explained that so far no tests have been carried out to determine whether there are wax residues as binding agents in the left eye socket. Due to the value of the bust, he considers taking a sample for further analysis unlikely. In addition, he mentioned the slight damage below the eye, which could indicate that the previously existing pupil made of rock crystal had been severed. There were also traces of blue paint in the left eye, which are also present in the right.

Depending on the suspected reason for the lack of the left eye, this led to different theses. Assuming that the bust remained unfinished, it is believed that the queen died or that the city of Akhet-Aton was suddenly abandoned. On the other hand, the work was not made for installation in a royal palace or a temple, but rather, in its masterful processing, may have served as a sculptural model for further busts of Nefertiti. According to Hermann A. Schlögl , it was specific for so-called “workshop samples” that they were incomplete in order to enable the sculptor to “follow the manufacturing process more easily through the details that were not yet finished or the preliminary drawings that were still recognizable.” The unfinished The left eye thus served as a template for the elaboration of the intricacies of the sculptural work on the eye.

Since Nefertiti is no longer mentioned in the contemporary records after the year 12 or the year 13 in the reign of Akhenaten, it was considered for some time that she had fallen into "disgrace", which had an effect on the processing of the portrait. The queen's eye disease was also suspected. A hieratic inscription discovered in 2012 in the quarry of Deir Abu Hinnis, however, mentions a “year 16, 3rd month, day 15” in Akhenaten's reign. Compared to other portraits or reliefs of the queen, the bust of Nefertiti is the only object so far that is missing the left eye.

The lack of the left eye has also been discussed in novels about Nefertiti and Akhenaten or in popular scientific literature . In his book Nefertiti from 1975 , Philipp Vandenberg follows the conclusion of the assumptions made by Egyptologists of that time that the portrait of the queen remained unfinished. He justifies this with the fact that the sculptor Thutmose did not complete the portrait out of spurned love in order to punish the queen. Christian Jacq leaves in his novel Nefertiti's daughter , the Great Royal Wife of Akhenaten blind before she dies.

Investigations

The first examination of the bust was carried out by Friedrich Rathgen in the 1920s . Ludwig Borchardt published the results in 1924. The sculptor Richard Jenner examined the bust in 1925 during his restoration work. Further analyzes and measurements followed in 1950, 1969 and 1982. In 1986 the result published by Borchardt on the plaster of paris was corrected. The more recent chemical investigation showed that it was a so-called gypsum - anhydrite mixture ( stucco ), which was also found on other objects from the Amarna period. In 1989 the Egyptologist Rolf Krauss proved that the bust had been worked precisely according to the specifications of a grid system . The scale is 26 finger widths of 1.875 cm each and gives the total height of almost 50 cm.

So far, the bust has been examined twice by means of computer tomography (CT) (1992 and 2006) in order to determine the manufacturing technique and the preservation or damage condition non-destructively. As early as 1990, the portrait head of Queen Teje (ÄMP 21834) was subjected to a detailed analysis in this way. It counts as the second main work of art of Egyptian art in the Egyptian Museum Berlin.

Due to some flaking of the thin layer of plaster on the left side of the blue crown and the visible layers of stucco on the shoulders, it was known that the core of the bust was made of limestone and covered with plaster and worked. Rudolf Anthes mentioned this in 1961 in The Head of Queen Nefertiti . The examinations were carried out in 1992 in the radiological department of the Charlottenburg Clinic of the Free University of Berlin and gave an exact picture of these processes. It was found that the unevenness and defects of the limestone core with the fine work were compensated by the stucco worked over it. So the shoulders in the limestone material are not at the same height and the neck is longer and thinner. The blue crown was originally tighter than in the image of the current bust.

The horizontal images at eye level also made it possible to measure the density of the material behind the rock crystal of the right eye. The density found corresponded to that of human adipose tissue and suggested that it was wax. The considerable corrections made to the limestone core by the stucco work also led to the conclusion that the bust is a sculptor's model. In comparison, sculptures or statues that were used in tombs or temples did not have such massive reworking with plaster of paris.

Due to the technical advances, the bust of Nefertiti was therefore again 14 years later in cooperation with National Geographic and Siemens Medical Solutions under the direction of Alexander Huppertz, the head of the Imaging Science Institute (ISI) of the Berlin Charité , and supervision of Dietrich Wildung again using CT scanned. The investigation carried out in 2006 made it possible to see the structures of the limestone core of the bust more clearly and presented them in much more detail than the first investigation in 1992.

Dietrich Wildung assessed the examinations of the bust:

“The portrait that the limestone core depicts is not very characteristic. The bust itself looks more individual, has more fascinating facial features. "

The core of the bust showed “a long, thin neck and crooked shoulders”. There was a lot of reworking by applying plaster, some with a thickness of up to 4 cm. On the one hand, corrections were made to the chiseled limestone, on the other hand, very fine wrinkles were subsequently incorporated in the last layer of the plaster of paris in the cheek area below the eyes. Wildung described this as “a typical process in the sculptor's studio”. This subsequent fine-tuning of the plaster of paris is evidence of the careful treatment of the queen's face. In order to better bring out the portrait of Nefertiti, the bust of Nefertiti was illuminated differently than before in the new presentation in the Altes Museum. She no longer appeared as the “pretty girl”, but as a mature, older woman.

When comparing the analyzes of the CT images from 1992 and 2006 and further evaluations of the image data, however, employees of the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing came to a different conclusion: There is no second face of Nefertiti, and this only exists virtually. Alexander Huppertz rejected the allegations about the investigation he carried out and the results as unfounded: “He doesn't want to swear that the original face looks exactly like it did on his 3-D scan. But I am convinced that there was a face. "

State of preservation

The bust is very well preserved apart from a few damage, such as the missing uraeus snake on the front of the crown above the forehead, parts of both ears or a larger superficial flaking of the plaster layer on the left side of the crown and slight break lines on the left shoulder. Small fragments of the ears could be reattached through restoration work in 1925. Like the pupil of the left eye, the chipped uraeus snake was not found in the rubble. The painting is in its original condition and has not yet been restored.

In the years since its discovery, the limestone bust had been exposed to different influences through its various stations. Their whereabouts were shaped by vibrations, temperature fluctuations and humidity. The Egyptologist Barry Kemp has headed the Amarna Project since 1977 and commented in 2007 on the individual stages of the bust, "It is a miracle that it has been preserved as an intact, beautiful statue".

The investigation from 2006 also revealed a poor connection between the materials used (limestone and stucco). Due to this inhomogeneity , the bust is not only susceptible to vibrations, touches or shocks, but also makes renovation impossible.

According to materials scientist Stefan Simon, the condition of the paint layer is also in a worrying state. Different studies show the color loss of the bust after 1913 and after 2005, with the color loss being greatest after the year of discovery. The painting on the bust also suffered damage as part of the art campaign for the Venice Biennale . In order to avoid further losses of the applied colors in the future, the bust received a new substructure made of stainless steel as a secondary assembly, through which it can be moved without contact.

As a further protection to preserve the color pigments, photography of the bust has been prohibited since February 2010, as the portrait of the queen was repeatedly photographed with flashlight despite prohibition signs.

Bust and amarna art

Although all the finds in the area of the excavation complex P 47 are unique in their elaboration, the bust of Nefertiti from the studio of the sculptor Thutmosis within this group and of all ten Nefertiti heads found there is the most outstanding work: It is the only one painted and finely worked out Portrait and counts as a masterpiece of ancient Egyptian art. The execution of the limestone bust stands out not only from depictions of all Egyptian epochs, but also from all other portraits, reliefs, statues or standing figures from the Amarna period. In contrast to the exaggerated and sometimes grotesque or ugly-looking depictions of the king, queen and children in the early days of Amarna art, the life-size bust of Nefertiti is symmetrical in its proportions and appears softer in terms of expression.

The shape of the bust is very unusual for an ancient Egyptian sculpture, as the head of a person was usually worked individually in order to later join it with a body made of other material. There are no traces of this bust, such as so-called “pegs” that can be plugged together, to indicate that it was ever intended for a composite statue of the queen.

Compared to other sculptural representations of the queen, this elaboration is unique. Dorothea Arnold differentiates between five types of portrayal among the portraits of the Queen:

- The Definite Image - The "ideal portrait" (Berlin Nos. 21300 and 21352)

- The Ruler - the "ruler" (Egyptian Museum Cairo, JE 45547)

- The Beauty - the "Beauty" (Berlin, No. 21220)

- Nefertiti in Advanced Age - the "older one" (Berlin, No. 21263) and

- The Monument - the "monument" (Berlin, No. 21358).

The bust of Nefertiti (No. 21300) is one of the ideal portraits. Other Egyptologists also see the Berlin bust as an idealized image of Nefertiti.

Rolf Krauss describes the Berlin bust as “completely constructed” and notes: “No human face has such mathematically precisely defined proportions. Nefertiti's head is an ideal image. ”Using a grid, he determined that the basic dimensions of the bust are about a finger wide (1.875 cm). These are the smallest longitudinal dimensions used in ancient Egypt. In comparison, the previously used units of measurement in the character grid were about four fingers wide, corresponding to a palm (7.5 cm). The perfect symmetry of the bust has been emphasized again and again among art historians. The queen's chin, mouth, nose and the uraeus serpent enthroned on her head lie without any deviation in a vertical axis of the face. However, this accuracy only affects the face of the queen portrait. The workings of the crown on both sides do not match in symmetry, as do the two shoulders. For example, the left side of the crown is a little wider than the right and the right shoulder is a little wider than the left. The symmetry of the face becomes particularly clear when viewed in mirror image, as both sides appear completely the same. The queen bust thus has a key position within Amarna art, as it stands out from all previous representations through a strict "numerical" system. "It undoubtedly represents the prototype of a new face for the queen in its purest form."

"The beauty"

(Berlin, No. 21220, quartzite , height 30 cm)"The monument"

(Berlin, No. 21358, granite , height 23 cm)

Despite numerous depictions of the queen in the form of reliefs, portrait heads or statues, the true appearance of Nefertiti is unknown.

Loan and return requests

After the first exhibition in 1924

Egypt's first request for return was made after the bust was first publicly exhibited in 1924 in the New Museum in Berlin . Pierre Lacau , successor to Gaston Maspero in the office of director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service ( Service d'Antiquités Égyptiennes ) and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , immediately asked for the bust back. The Egyptian government followed suit. Lacau did not question the legal division of the find in equal parts, but gave "moral" reasons for the return claim. The following year, Borchardt did not receive an excavation license in Egypt.

The secretary of the German Orient Society, Bruno Güterbock, who was present in Amarna on the day the find was divided, reported to a colleague on August 12, 1924 in a private letter with the note “strictly confidential!” The tactics with which the excavator Borchardt had succeeded , "To save the bust for us". Güterbock ruled that "any doubts that emerged about the lawful acquisition" were solely "to blame" for Borchardt. Shortly before, the figure was presented to the world for the first time in Berlin.

In 1929 Pierre Lacau visited Berlin, and the then director of the Egyptian Museum of the State Museums in Berlin, Heinrich Schäfer , was ready to return the bust to Egypt. James Simon, who gave the bust to the Berlin museums together with other finds from Amarna in 1920, agreed to this and Egypt made an offer: a statue of Ranefer ( Old Kingdom ) and a seated statue of Amenhotep, son of Hapu ( New Kingdom ) in exchange for the bust of Nefertiti. Borchardt, however, insisted that the collection should not be torn apart for research purposes. The Ministry of Science, Art and Education agreed to a return in exchange at this time. However, public opinion was that the bust of Nefertiti should remain in Berlin. In 1930 the ministry, headed by Adolf Grimme, decided against an exchange.

time of the nationalsocialism

On the anniversary of King Fuad I's assumption of power in 1933, the Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring planned to return the bust, which was apparently also supported by Joseph Goebbels for propaganda reasons . Adolf Hitler, on the other hand, declared the bust of Nefertiti an icon in a speech in the same year : “I will never give up the Queen's head. It is a masterpiece, a jewel, a real treasure. ”In her honor, the Chancellor planned to build a new large museum in the newly designed and renamed Germania city of Berlin, which provided a complete room for the bust only, and prohibited its return.

After the Second World War

In 1945 there was an internal German conflict over the ownership of the bust. The representatives of the Soviet occupation zone stated that the old collections of the state museums that had been relocated during the war were unlawfully withheld from them. The demand for a return of art and cultural goods to the pre-war locations was based on the so-called provenance principle . The representatives of the western zone, on the other hand, relied on the federal German legal situation and refused to export the bust and all other objects of the state museums in West Berlin to the eastern zone.

After the end of the Second World War, various American museums also showed their interest in German art treasures. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York was interested in the bust of Nefertiti, whose export to the United States was prevented by the arts protection officer Walter I. Farmer. After the exhibition of the bust of Nefertiti with other art objects in the State Museum Wiesbaden in 1946, Egypt again made claims to the portrait of the queen. It was planned that the bust would find its final place in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. Negotiations between Egyptian and American envoys followed. The result of the investigation by the American military government was that the bust was not one of the art objects stolen by the National Socialists and had been brought to Berlin "properly" in 1913. The press announced in 1947 that the bust of the Egyptian queen would remain in Germany.

In the past few years, especially from the 2000s, the bust of Nefertiti has been reclaimed several times from various quarters as a loan to Egypt. In addition to the former General Secretary of the Egyptian Antiquities Administration ( Supreme Council of Antiquities ), Zahi Hawass , the director of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo , Wafaa el-Saddik , also asked for a loan in 2006 . The Egyptian ambassador, Mohamed Al-Orabi , called the bust of Nefertiti for the opening ceremony of the Egyptian Museum in the Altes Museum “permanent representative of Egypt in Germany”, but in 2008 also requested a loan to Egypt and the establishment of an “Egyptian-German commission on transportability the Nefertiti ”. In 2007, Zahi Hawass asked to borrow the bust for an exhibition for three months to mark the opening of the new Egyptian Museum at the Pyramids . In this context, the then museum director Dietrich Wildung pointed out that Germany was planning to found a museum for “European art” in Alexandria , Egypt, which the European countries would like to thank Egypt.

In 2007 the campaign “Nefertiti goes on a journey” took place. The CulturCooperation e. V. called on the federal government in a letter to the State Minister for Culture and Media, Bernd Neumann , to loan the bust to Egypt. The possible loan of the bust met with rejection in the German Bundestag . The culture committee of the Bundestag declared on April 26, 2007 in Berlin that the handling of the limestone bust must be extremely careful for reasons of conservation and restoration . On May 9, 2007, the Bundestag member Evrim Baba sent a small request with the title “Colonial Looted Art” and in August of the same year with the title “Nefertiti goes on a journey”. The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation responded to the first inquiry with answers and corrections to the statements made in the campaign.

However, in recent years, Hawass has also increasingly made direct demands for the return of the bust, as Egypt had been deceived about the value of the bust at the time and she therefore left the country illegally. In Egypt, a commission was set up to review the facts and the papers at the time. At the opening of the Neues Museum in Berlin in October 2009, Zahi Hawass publicly stated:

“I will comment on this shortly, but not before the museum opens on Friday. If our research shows that Nefertiti left Egypt legally, I will not say anything more. If she has left Egypt illegally, which I am convinced of, I will officially reclaim her from Germany. "

When the new director of the Egyptian Museum Berlin, Friederike Seyfried , visited Zahi Hawass in Cairo, the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation pointed out in December 2009 that the negotiations were not about the bust of Nefertiti. There was also never an official request from the Egyptian state for return. Whether the sculpture would be made available for a temporary exhibition is still being examined. Only the results of the conservation examinations on the transportability of the bust are seen as decisive for a loan.

present

In March 2010, Seyfried announced that after examining all the documents, there were no doubts about the division of the find and that this was done in accordance with the provisions of the time.

On January 24, 2011, Zahi Hawass again requested the return of the bust in a letter to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation . Hawass also emphasized that Prime Minister Ahmed Nazif and Minister of Culture Farouk Hosny "expressly" supported the demand. The main argument for the return is the false declaration by Borchardt as worthless plaster work. However, this demand was rejected by Minister of State for Culture Bernd Neumann.

On the 100th anniversary of the discovery of the bust, Hermann Parzinger , President of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation , declared in December 2012 that he still rules out a return to Egypt: “Nefertiti is part of the cultural heritage of humanity. I do not consider a return simply out of magnanimity to be justifiable. "

Copies and suspicion of forgery

Copies of the bust

There are numerous duplicates of the bust of Nefertiti. In 1925, Richard Jenner carried out restoration work on the ears and remains of the uraeus snake on the limestone bust and began making a first copy. In the Gipsformerei , the oldest institution of the Staatliche Museen Berlin, replicas in the form of plaster casts of various important museum pieces from Berlin or European museums have been produced since 1819 , including the bust of Nefertiti. The material used is high quality alabaster plaster. The production of replicas of the bust of Nefertiti takes place on the basis of a master copy and the replicas correspond to an implementation in original size. At the end of the 1960s, the shape model that Tina Haim-Wentscher had made was replaced by one based on photogrammetry . However, this model was imprecise and had to be reworked by the restorer Joachim Lüdcke in order to obtain a suitable shape for the production of the replicas. In 2005, for example, the relocation of the bust from Charlottenburg to the Museum Island in the Altes Museum and its presentation at the new location were "rehearsed" with copies of the bust for security reasons.

In 2011, the bust of Nefertiti was measured with a 3D scanner , which enables the sculpture to be reproduced with an accuracy of hundredths of a millimeter. On this basis, the plaster molding workshop of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin produced a special edition of the bust, which was limited to 100 copies.

After all the finds from Amarna had been donated to the Prussian state, James Simon replaced the original bust in his house with a copy. Today it is probably owned by Simon's descendants. The fascination for the portrait of the queen also prompted Kaiser Wilhelm II to have a copy made. However, he had a second eye inserted into this piece. In 1918 the emperor even took the bust with him into exile in Doorn , the Netherlands . This replica can still be found today in Haus Doorn , the exile seat of Kaiser Wilhelm II. The imperial replica was on view in 2010 in the special show "History and Adventure of Archeology" at the Ruhr Museum in Essen, and in 2011 in the special exhibition "Sisi en Wilhelm II - Keizers op Corfu ”in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden.

Hitler is also said to have commissioned one or even several exact copies of the bust. It was said that it was made to deceive the Egyptians and that Hitler wanted the original for his private collection.

The ZDF attacked the thesis about the existence of a copy of Hitler in a documentary 2007: On the orders of Major bust of Nefertiti from Berlin Zoo bunker had been outsourced. It was in a box with the number 28 when it left Berlin, but is said to have arrived in Merkers in a box with the number 34. It would therefore be questionable whether the bust of the Queen in the Berlin Museum is real. The description is contradictory, however, because the major's assertion on the one hand does not coincide with the protocols according to which the bust had already been transported to the salt mine in Thuringia at that time. On the other hand, it was Hitler himself who gave the order to salvage the art treasures.

The BZ published a report in January 2008, according to which the fashion manufacturer Shangri-La was in possession of this copy, which had been rescued from "Hitler's private museum". They have a stamp with the inscription AH 537 on the base. It could also be the original, so there is a copy in the Berlin Museum. Dietrich Wildung disagreed by stating that the CT examination revealed that there were no doubts about the originality of the bust in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin and that it was not a copy.

Suspicion of forgery

At the beginning of the 1980s the rumor arose that Ludwig Borchardt had forged the queen's bust, dug it in and then dug it up again on December 6, 1912 in order to impress an announced group of visitors, among them the Saxon Prince Johann Georg , with the find.

Rolf Krauss commented on the rumors of that time: "With a suitable interpretation of the facts, this hypothesis fits both Borchardt's urgent wish to have the bust awarded when the find was divided and his subsequent attempt to withhold it from the public." The excavation team did Color pigments were also found and it was possible to process these old materials again, but the 1987/1988 first targeted investigation showed that a so-called lime-gypsum-anhydrite mixture was used for the bust. This mixture was not yet known at the time of the excavation and without a chemical analysis it would not be possible to forge the material. At this point in time, he considers an art-archaeological assessment to be difficult, as not all Amarna finds have been published and the publication status for the bust of Nefertiti is also incomplete. In 2009, however, he commented on the fact that Borchardt had withheld the bust, "that it would have been easy to commission a stonemason with a forgery in the meantime ."

In March 2009, the Swiss art historian Henri Stierlin published the thesis that the bust of Nefertiti was only made at the beginning of the 20th century. It would have been made on behalf of Ludwig Borchardt without the intention of forgery, who wanted to present a necklace on the bust that had been found during excavation work in Egypt. According to Stierlin, there are also indications on the bust itself that it is not a 3400-year-old Egyptian artifact: The fact that Egyptology assumes that the bust intentionally had no left eye would, however, be an insult the ancient Egyptians who believed that statues were real people. Stierlin also points out that the shoulders of the bust were cut off vertically, but that the ancient Egyptians always set the shoulders of statues horizontally.

Independently of Henri Stierlin, the writer Erdoğan Ercivan also dealt with archaeological forgeries and also doubts the authenticity of the bust of Nefertiti. According to him, Ludwig Borchardt's wife was the model for the bust, which would explain that Borchardt wanted to keep the bust "under lock and key".

The former director of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin, Dietrich Wildung , rejected Stierlin's thesis as "undoubtedly incorrect" and stated that no trace elements from modern materials could have been found on the bust. Such a perfect fake would not have been possible at the time. Already after the first CT examination in 1992, Wildung mentioned as a casual result: "The complicated structure of the bust from a stone core with plaster additions banishes the rumors about a modern production of the Nefertiti bust into the realm of the imagination."

André Wiese, curator at the Antikenmuseum Basel , also described in an interview "the allegation of forgery as simple nonsense" and the allegations as "completely baseless and unbelievable". The bust had been examined several times and all analyzes, x-ray examinations as well as the circumstances of the find indicate the authenticity of the bust. The color pigments were unequivocally determined to be antique, with plaster of paris and stone being “old” materials, for which an age cannot be given. However, Wiese sees the decisive point as the fact that after the Nefertiti bust, an almost identical bust of Akhenaten was found. In order to forge the bust of Nefertiti, this bust should have been known to Akhenaten. A comparable bust of Akhenaten is in the Louvre in Paris.

Zahi Hawass also contradicts Henri Stierlin's thesis: Stierlin is not a historian and his claim that the bust is a fake is pure fantasy. Regarding the vertically cut shoulders, he notes that Akhenaten had introduced a new art form during his reign. The bust was made with two eyes, the left one later being destroyed. In response to Stierlin's argument that Borchardt knew it was a fake, Hawass replied that the report on the discovery was surprisingly detailed.

Stefan Simon, materials scientists of the National Museums of Berlin belonging Rathgen research laboratories , took to this question extensively forgery position. He noted in conclusion, as Rolf Krauss, that the material used for the bust a so-called Amarna-Mix is a gypsum - anhydrite mixture with proportions of limestone, which in 1912 was not yet known. A forgery was impossible without this knowledge.

Cultural meaning

Since its first exhibition in 1924, the bust of Nefertiti has been an integral part of Berlin museum culture and has attracted numerous visitors ever since. As crucial to the then rapidly growing interest in the bust and on ancient Egypt not only the appearance of the bust, but also finding the untouched tomb (is KV62 ) of Tutankhamun by Howard Carter saw in 1922, which according to the following years its discovery led to a worldwide Egyptomania . Among all the ancient Egyptian art objects found so far , the bust of Nefertiti is perhaps comparable in shape to the gold mask of Tutankhamun.

The bust, considered a media icon , graced numerous front pages of newspapers and magazines and thus became a cover girl . For women, the portrait was style-defining in the early 1920s, who copied the queen's makeup. The press often describes "Nefertiti" as the best known or most beautiful "Berliner".

The motif Nefertiti

The bust of the queen can also be found today worldwide as a very popular motif for jewelry, calendars, writing pads, postcards and replicas made of artificial casting in kitsch or artistic processing and as an original representation. Art prints or painted papyri often show the bust of Nefertiti with two intact eyes.

Between July 1988 and January 1989 a 70 and 20 pfennig stamp was issued in Germany showing the bust of Nefertiti. On January 2, 2013, the first day of issue, Deutsche Post AG again issued a special postage stamp (worth € 0.58) with the bust of Nefertiti. The image of the bust of Nefertiti can often be found as an advertising medium. In the Berlin election campaign in 1999 , Bündnis 90 / Die Grünen chose the bust as a poster with the slogan: “Strong women for Berlin”.

The bust itself was placed on the bronze torso of a naked woman for a short time in 2003 as part of an art campaign, which was created as a work of art for the Venice Biennale by the two Hungarian artists András Gálik and Bálint Havas. In the action, which was shown for the first time at the Biennale on June 15, 2003, the artists attempted “to combine the 3,000-year-old ideal of beauty with a modern woman's body”. Thereupon there were great protests and outrage on the part of Egypt: On the one hand because of the handling of the valuable limestone bust, on the other hand because of the display on a naked woman's body.

Nefertiti Hack

The dataset of a 3D scan of the bust is freely accessible on the internet. Since this data comes from a data leak, downloading is still in a legal gray area, but using the data is considered to be harmless.

The dataset of a 3D scan carried out by the museum is now also available under a CC BY-NC-SA license.

The Other Nefertiti was a digital art theft that occurred at the end of 2015 in the north dome hall of the Neues Museum, Berlin. The bust of Nefertiti was digitally reproduced unnoticed despite the high security standards, which also prohibited the creation of images. The data set generated with these 3D scans was published a little later under the public domain . Two artists later confessed to the act in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung. The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation has not yet taken any legal action.

See also

literature

- Egyptian Museum Berlin. Hartmann, Berlin 1967, p. 71, no.767.

- Rudolf Anthes : The Head of Queen Nefertiti. Formerly the Berlin State Museums. = Nefertiti Ete. 3rd edition, Mann, Berlin 1961 (English).

- Dorothea Arnold : The Royal Women of Amarna. Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 1996, ISBN 0-87099-816-1 , pp. 65-70.

- Peter France: The robbery of Nefertiti. The sack of Egypt by Europe. Diederichs, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-424-01231-9 .

- Rolf Krauss : 1913–1988. 75 years bust of Nefertiti - Nefret-iti in Berlin. In: Yearbook Prussian Cultural Heritage. Vol. 24, 1987, ISSN 0342-0124 , pp. 87-124 and Vol. 28, 1991, pp. 123-157 (Part 1 also as a special edition: Association for the Promotion of the Egyptian Museum in Berlin-Charlottenburg, Berlin 1988).

- Jürgen Settgast : Bust of Nefertiti. In: Nefertiti - Akhenaten. von Zabern, Mainz 1976, No. 81.

- Friederike Seyfried : The bust of Nefertiti - documentation of the find and the division of the find 1912/1913. In: Yearbook Prussian Cultural Heritage. Vol. 46, 2010, ISSN 0342-0124 , pp. 133-202.

- Friederike Seyfried: In the light of Amarna. 100 years of the discovery of Nefertiti. Imhof, Petersberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-86568-842-2 .

- Oliver Simons: The Rape of Nefertiti. In: Ulrich van der Heyden , Joachim Zeller (ed.): “… Power and share in world domination.” Berlin and German colonialism. Unrast, Münster 2005, ISBN 3-89771-024-2 , pp. 191-196.

- Bénédicte Savoy (Ed.): Nefertiti. A Franco-German affair 1912–1931. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2011, ISBN 978-3-412-20811-0 .

- Joyce Tyldesley : Egypt's Sun Queen. Biography of Nefertiti. Limes, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-8090-3017-1 , pp. 288-293.

- Joyce Tyldesley: Myth of Egypt. The story of a rediscovery. Reclam, Stuttgart 2006, ISBN 3-15-010598-6 , pp. 253-256.

- Gitta Warnemünde: The bust of Nefertiti. From the desert to the island - a journey with obstacles. In: Kemet issue 3/2010, ISSN 0943-5972 , pp. 34-39 ( PDF; 0.6 MB ).

- Carola Wedel : Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. von Zabern, Mainz 2005, ISBN 3-8053-3544-X , pp. 11-26; Pp. 83-88.

- Dietrich Wildung : Insights. Non-destructive examinations on ancient Egyptian objects. In: Yearbook Prussian Cultural Heritage. Vol. 29, 1992, pp. 148-151.

- Dietrich Wildung: The bust of Nefertiti. Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection, Berlin (= Vernissage Meisterwerke. ISSN 1867-6391 ). Vernissage-Verlag, Heidelberg 2009.

- Martina Dlugaiczyk: Series star Nefertiti. New sources on the 3D reception of the bust before the Amarna exhibition of 1924. In: Christina Haak , Miguel Helfrich (Hrsg.): Casting. An analog route into the age of digitization. A symposium on plaster molding of the State Museums in Berlin. arthistoricum.net, Heidelberg 2016, doi: 10.11588 / arthistoricum.95.114 ; under license: ISBN 978-3-946653-19-6 , pp. 162–173. ( online publication ).

- Martina Dlugaiczyk: Thutmose vs Tina Haim-Wentscher - the model of Nefertiti as a model. In: David Ludwig, Cornelia Weber, Oliver Zauzig (eds.): The material model. Object stories from scientific practice. Fink, Paderborn 2014, ISBN 978-3-7705-5696-0 , pp. 201-207 (reception history).

Web links

- Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection Berlin; Presentation of the Association for the Promotion of the Egyptian Museum e. V .: Room 2.10: Bust of Nefertiti

- Exhibition: In the light of Amarna. 100 years of the discovery of Nefertiti. (December 7, 2012 - April 13, 2013)

- Ägyptisches Museum Berlin: Why is Nefertiti so famous? / Who actually was Nefertiti?

- Campaign 'Nefertiti goes on a journey'. ( Memento from October 5, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) On: nofretete- geht-auf-reisen.de

- ZfP-Zeitung 116, October 2009 : The second face of Nefertiti

- Spiegel-online (culture): Dispute over Berlin's Nefertiti. Interview with Zahi Hawass, October 18, 2009

- 3D model including the 3D scan data with texture for download as Wavefront OBJ , Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin - Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz , CC BY-NC-SA

Remarks

- ↑ Dating after Rolf Krauss in: Thomas Schneider : Lexikon der Pharaonen. Albatros, Düsseldorf 2002, ISBN 3-491-96053-3 , p. 318.

- ↑ The dates given for the first exhibition of the bust are 1923 and 1924. Ludwig Borchardt's work Portraits of Queen Nefertiti appeared in 1924 with numerous photos of the bust, but was dated 1923.

- ↑ Complete translation of the line: "(The) mistress of both countries, Nefertiti, she live forever in infinite duration." ( Nbt t3wj (Nfr nfrw Jtn Nfr.t jy.tj) tj ˁnḫ ḏd nḥḥ )

- ↑ compare with this Carter No. 256,4,0 (Diadem) , The Griffith Institute: Tutankhamun: Anatomy of an Excavation (English).

- ↑ There are different statements about this within Egyptology: According to Hermann A. Schlögl, Nefertiti died after the 13th year of reign (in: Das Altegypt. P. 238); According to Marc Gabolde, Nefertiti lived in Akhenaten's 17th year of reign and died shortly before her husband (in: The secret of the golden coffin , p. 20).

- ↑ The chemical analysis was carried out in 1986.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Jürgen Settgast: Exhibition catalog Nefertiti - Akhenaten. No. 81.

- ↑ a b Welt Online: The second secret face of Nefertiti. March 31, 2009.

- ↑ Queen Nefertiti: Legends of Incest and Concubines. On: stern.de from October 16, 2009.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 22.

- ↑ a b Dietrich Wildung: The bust of Nefertiti. P. 7.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 23.

- ↑ Egyptian Museum Berlin: The bust of Queen Nefertiti. P. 71.

- ^ Ludwig Borchardt, U. Herbert Ricke: The houses in Te11 el-Amarna. Edited by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft in collaboration with the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department, Mann, Berlin 1980, ISBN 3-7861-1147-2 , p. 97.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 24.

- ^ Ludwig Borchardt, U. Herbert Ricke: The houses in Tell el-Amarna. P. 98.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 25.

- ↑ www.n24.de ( Memento of the original dated February 7, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Nefertiti in Berlin: A Chronology. On: nofretete- geht-auf-reisen.de ( Memento from September 11, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ A queen remains . In: Der Spiegel . No. 1 , 1947 ( online - Jan. 4, 1947 ).

- ↑ DeutschlandRadio: Hieroglyphs around Nefertiti. ( Memento of September 11, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) March 1, 2005.

- ↑ Splendid charm of ruins for Nefertiti. , October 16, 2009 ( Memento from February 10, 2013 in the web archive archive.today )

- ^ Hermann A. Schlögl: The old Egypt. History and culture from the early days to Cleopatra. Beck, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-406-54988-8 , p. 225.

- ↑ Athena Van der Perre: Nefertiti (for the time being) last documented mention. In: In the light of Amarna - 100 years of the discovery of Nefertiti. Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection State Museums in Berlin. Imhof, Petersberg 2012. ISBN 978-3-86568-842-2 , pp. 195-197.

- ↑ a b Berliner Morgenpost: Guesswork on Queen Nefertiti. May 7, 2009.

- ↑ a b Dietrich Wildung: The bust of Nefertiti. P. 4.

- ↑ a b c d e f Spiegel-online: Dispute about silent beauty. May 15, 2009.

- ↑ Pupil in memory . In: Der Spiegel . No. 20 , 1997, pp. 211 ( online - May 12, 1997 ).

- ↑ a b Ludwig Borchardt: Diary entry for the discovery of the Nefertiti bust. Egyptian Museum Berlin, inventory no. 21357.

- ^ Berlin, Egyptian Museum of the State Museums Berlin Prussian Cultural Heritage: Nefertiti - Akhenaten. Zabern, Mainz 1976, No. 80

- ↑ a b Exhibition catalog Ägyptisches Museum Berlin, 1967, No. 767: Bust of Queen Nefertiti, p. 71.

- ↑ a b Joyce Tyldesley: Myth of Egypt. The story of a rediscovery. P. 254.

- ↑ a b Rudolph Anthes: Nefertiti - The Head of Queen Nefertiti. P. 6.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 13.

- ↑ a b Joyce Tyldesley: Myth of Egypt. The story of a rediscovery. P. 253.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 11.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The bust of Nefertiti . P. 15.

- ↑ a b c Dietrich Wildung: The bust of Nefertiti. P. 13.

- ^ A b Dorothea Arnold: The Royal Women of Amarna. Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. P. 69 (English).

- ↑ Joyce Tyldesley: Egypt's Sun Queen. Biography of Nefertiti. P. 292.

- ^ A b Dorothea Arnold: The Royal Women of Amarna. Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. P. 67 (English).

- ↑ Nicholas Reeves: Fascination Egypt. P. 134.

- ↑ a b Digital Journal: Egypt's Rubbishes Claims that Nefertiti Bust is 'Fake' , May 12, 2009 (English).

- ↑ a b Joyce Tyldesley: Egypt's Sun Queen. Biography of Nefertiti. P. 291.

- ^ Hermann A. Schlögl: Akhenaten. Rowohlt, Hamburg 1986, ISBN 3-499-50350-6 , p. 79.

- ↑ Athena Van der Perre: Nefertiti (for the time being) last documented mention. In: In the light of Amarna - 100 years of the discovery of Nefertiti. Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection State Museums in Berlin. Imhof, Petersberg 2012. ISBN 978-3-86568-842-2 , p. 197.

- ^ Philipp Vandenberg: Nefertiti , p. 47.

- ↑ a b National Geographic: The Beauty of the Nile. ( Memento of the original from April 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 2001.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: Insights. Non-destructive examinations on ancient Egyptian objects. P. 134.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 14.

- ↑ a b Dietrich Wildung: Insights. Non-destructive examinations on ancient Egyptian objects. P. 148.

- ^ A b Siemens: Siemens riddles the interior of Nefertiti .

- ↑ a b Der Tagesspiegel: Nefertiti: Your second face. July 25, 2007.

- ↑ ZfP-Zeitung 116: The second face of Nefertiti. October 2009.

- ↑ BZ-online: Doesn't Nefertiti have a second face? October 13, 2009.

- ^ National Museums in Berlin, Egyptian Museum: Bust of Nefertiti. ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ a b c d ZDF terra-x: The Odyssey of Nefertiti: Original and Forgery. ( Memento of the original from July 14, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , July 27, 2007.

- ↑ Der Tagesspiegel: No more photos of Nefertiti. February 17, 2010.

- ↑ Dietrich Wildung: The bust of Nefertiti. P. 8.

- ^ Dorothea Arnold: The Royal Women of Amarna. Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. New York 1996, pp. 65-83.

- ^ A b Dorothea Arnold: The Royal Women of Amarna. Images of Beauty from Ancient Egypt. P. 68.

- ↑ Michael E. Habicht : Nefertiti and Akhenaten. The secret of the Amarna mummies. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2011, ISBN 978-3-7338-0381-0 , Fig.XI-a and XI-b

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 26.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 83.

- ↑ Der Spiegel 49/2012: The abducted queen. , December 3, 2012, accessed February 18, 2018.

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, p. 85.

- ↑ ZDF, terra-x: The Odyssey of Nefertiti: Scandal about Nefertiti ( Memento of the original from July 14, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , July 29, 2007.

- ↑ a b museo-on.de: Small inquiry from Evrim Baba: Koloniale Raubkunst ; Printed matter 16/10754 of May 9, 2007 (PDF; 280 kB)

- ↑ Carola Wedel: Nefertiti and the secret of Amarna. Mainz 2005, pp. 85, 87.

- ↑ A queen remains. The most famous stone head . In: Der Spiegel . No. 1 , 1947 ( online - Jan. 4, 1947 ).

- ^ Spiegel Online : Nefertiti too old to travel? April 13, 2007.

- ^ Taz.de: Bundestag holds Nefertiti in Berlin. April 27, 2007.

- ↑ evrimbaba.de: Small inquiry from Evrim Baba: Nefertiti goes on a journey ; Printed matter 16/11128 from August 16, 2007 ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 95 kB).

- ↑ Der Tagesspiegel: "We are not hunters of the lost treasure". October 13, 2009.

- ↑ Press release Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation: [ = none & sword_list [] = negotiations & sword_list [] = on & sword_list [] = nefertiti & no_cache = 1 no negotiations on Nefertiti. ], December 18, 2009.

- ↑ Egypt reclaims the bust of Nefertiti - tug of war for the beautiful queen ( memento from January 27, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) from January 24, 2011.

- ^ Matthias Schulz: Archeology: The kidnapped queen . In: Der Spiegel . No. 49 , 2012 ( online - December 3, 2012 ).

- ↑ DPA-InfolineRS: Archeology: Egypt wants to continue returning Nefertiti. In: Focus Online . February 20, 2011, accessed October 14, 2018 .

- ↑ BZ online: Hermann Parzinger: Nefertiti stays a Berliner , December 3, 2012.

- ↑ Gipsformerei der Staatliche Museen zu Berlin ( Memento of the original from June 6, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Rolf Krauss: 1913–1988. 75 years bust of Nefertiti - Nefret-iti in Berlin. P. 120.

- ↑ Welt Online : Nefertiti copies rehearse the move. March 1, 2005.

- ^ Dpa: Museums: Nefertiti replica accurate to a hundredth of a millimeter. (No longer available online.) In: Zeit Online. August 17, 2011, archived from the original on March 11, 2016 ; accessed on February 24, 2016 . Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Rolf Krauss: 1913–1988. 75 years bust of Nefertiti - Nefret-iti in Berlin. Pp. 94, 119.

- ^ RP Online: Nefertiti for Kaiser Wilhelm February 11, 2010.

- ↑ Berliner Umschau: Nefertiti Superstar , October 26, 2009 ( Memento from January 5, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Rolf Krauss: 1913–1988. 75 years bust of Nefertiti - Nefret-iti in Berlin. P. 119.

- ^ Archeology Headlines: Nefertiti's Hidden Face Proves Famous Berlin Bust is not Hitler's Fake . April 3, 2009 (English).

- ↑ BZ Online: Nefertiti's Nazi sister emerged. January 3, 2008.

- ↑ a b Rolf Krauss: 1913–1988. 75 years bust of Nefertiti - Nefret-iti in Berlin. P. 92.

- ^ Rolf Krauss: 1913–1988. 75 years bust of Nefertiti - Nefret-iti in Berlin. P. 93.

- ^ Matthias Schulz: Archeology: Krimi um die Königin . In: Der Spiegel . No. 22 , 2009 ( online - May 25, 2009 ).

- ^ Henri Stierlin: Le Buste de Néfertiti, une imposture de l'égyptologie? Infolio, Gollin 2009.

- ↑ Erdoğan Ercivan: Missing Link of Archeology. Concealed finds, forged museum exhibits and archaeologists exposed as fraudsters. Kopp 2009.

- ↑ The Guardian (UK): Is this Nefertiti - or a 100-year-old fake? May 7, 2009 (English).

- ↑ Welt Online: Researcher considers Berlin Nefertiti to be a fake. May 5, 2009.

- ↑ Thurgauer Zeitung , Interview with André Wiese: The allegation of forgery is simple nonsense , May 7, 2009.

- ^ Regine Schulz, Matthias Seidel: Egypt. The world of the pharaohs. P. 203.

- ↑ National Geographic Germany: The Beauty of the Nile. ( Memento of the original from April 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. 2001.

- ^ Postage stamps with images from the museums in Berlin ( Memento from September 12, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ German Post Philately: mint - The Philatelic Journal. January / February 2013.

- ↑ Berliner Zeitung: Nefertiti in Parliament , August 21, 1999.

- ↑ welt.de: Nefertiti on her own two feet. May 21, 2003.

- ↑ Der Tagesspiegel: Art action with naked Nefertiti annoys Egyptians. June 10, 2003.

- ↑ Nefertiti Hack

- ↑ Eva-Maria Weiß: Creative Commons: Nefertiti 3D-Scan now freely available. In: heise online . November 15, 2019, accessed November 16, 2019 .

- ↑ BUST OF NEFERTITI, FOIA Results - Download Free 3D model by CosmoWenman (@cosmowenman). Sketchfab, November 6, 2019, accessed November 16, 2019 .

- ^ Carolin Wiedemann: Art Action Freedom for Nefertiti! In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . November 30, 2015, accessed February 23, 2016 .