James Simon

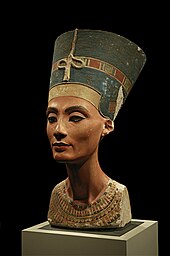

Henri James Simon ([Siːmɔn], born September 17, 1851 in Berlin ; † May 23, 1932 ibid) was an entrepreneur in Berlin during the Wilhelmine era, a sponsor of the Berlin museums, a discussion partner of Kaiser Wilhelm II and the founder and financier of numerous charitable institutions . The portrait sculpture of Nefertiti , which he donated to the Egyptian Museum in Berlin , is permanently associated with his name . Simon is considered to be one of the most important art patrons of his time.

Life

Simon was of Jewish faith . His father Isaac (1816–90) from Pyritz in Pomerania , then a tailor in Prenzlau , had moved to Berlin in 1838. He quickly became wealthy with a shop for men's clothing, then with a cotton middleman founded in 1852 with his brother Louis (1828–1903). The impetus for the really great wealth of the family was then a historical event overseas: the civil war in the USA , during which the export of cotton to Europe came to a standstill. A cotton crisis arose in Prussia in 1863/64, and the Simon brothers were able to sell their large stocks at five times the price. The company grew rapidly, from the 1870s to the beginning of the First World War in 1914 it was the most important cotton company on the European continent. The Simon brothers came to be known as the "Cotton Kings," a term that was later used for Isaac's son James.

James Simon was born on September 17, 1851, his mother Adolphine (1820–1902) was the daughter of a rabbi . James attended the renowned Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster in Berlin, developed a fondness for Latin , Greek and Ancient History , and played the piano and violin regularly. He was less interested in math. He would have liked to study classical philology , but complied with his father's wishes and, after graduating from high school, began practical training as an apprentice in the family company in 1869. In Bradford , England , at that time the center of the British textile industry , he completed a six-month traineeship and finally joined his father's company as a junior partner at the age of 25. In 1883 he became a member of the Society of Friends , an important association of Berlin Jewry. After the death of his father in 1890, he ran the company initially with his uncle Louis, and later with his cousin Eduard . In addition to diverse cultural and social interests and activities, James Simon was also extremely successful in business. In 1911 he had a fortune of around 35 million marks and an income of 1.5 million marks. This put him in seventh place in the ranking of millionaires in the capital of the empire.

At the age of 27, James married Simon. His wife Agnes (1851–1921) also came from a respected family in the Berlin textile industry. Her parents were Helena, nee Arndt, and Leonor Reichenheim (1814–1868), partners in the textile company N. Reichenheim & Sohn , member of the Prussian House of Representatives , the North German Reichstag and the Berlin City Council, co-founders of the National Liberal Party and unpaid city councilor of Berlin.

In 1886 the Simon couple moved to the upper floor of their father's newly built villa at Tiergartenstrasse 15 a (former house number 5 a), one of the best addresses in Berlin during the imperial era. The three-storey villa, decorated with numerous art objects, was completely redesigned in 1908 by the architect Alfred Breslauer . The house burned down in World War II , the ruins were demolished and cleared in May 1957. The State Representation of Baden-Württemberg has stood on this property since 2000. The Simons had three children: Helene (1880-1965), who married the lawyer Ernst Westphal, a grandson of Alexander Mendelssohn , Heinrich (1885-1946) and (the mentally handicapped) Marie-Luise (1886-1900).

James Simon was a famous and socially recognized man within the scope of what was possible with the latent anti-Semitism of the time. Friends and co-workers described him as extremely correct, very cautious, always careful to separate personal and professional matters. He was offered titles and honors, which he also accepted so as not to offend anyone, presumably also with quiet satisfaction, but he evaded any public ceremony. James Simon died on May 23, 1932. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery on Schönhauser Allee in Berlin in field L3, G3. Kaiser Wilhelm II, long in exile in the Netherlands in the Doorn house , had a wreath laid on the grave.

The "Imperial Jews"

Chaim Weizmann , Zionist and later Israel’s first President , gave a small group of prominent Berlin Jews the very unfriendly term "Kaiser Jews" because of their proximity to Wilhelm II. This group included above all Albert Ballin , Director General of HAPAG , and since 1901 also James Simon; Other participants in the round were coal entrepreneur Eduard Arnhold , bankers Carl Fürstenberg and Paul von Schwabach and Emil and Walther Rathenau from AEG . Wilhelm II first consulted these men about their economic expertise. This resulted in informal discussion evenings devoted to a wide variety of topics. Simon's advice was particularly sought after when it came to Jewish matters; after a while, his presence was required whenever the emperor had to decide on Jewish matters. Simon always made these contributions as a private person, without any official status.

Such a relationship of trust was not a given. The emperor undoubtedly represented an arch-conservative sentiment and also had anti-Jewish resentments. Simon, on the other hand, was a co-founder of the “ Association for Defense against Anti-Semitism ” , his political standpoint was liberal, and towards the end of his life he developed sympathy for social democracy . Apparently these differences did not affect her personal relationship. Even after the Kaiser abdicated in 1918, contact was maintained from both sides, although Simon never spoke out in favor of a return to the monarchy , but instead actively supported the Weimar Republic .

The art patron

Excavations in Egypt

The common interests, of course, went far beyond questions of economy and Judaism. One of Wilhelm II's favorite projects was the establishment of the " Kaiser Wilhelm Society for the Advancement of Science" - Simon donated the unusually high amount of 100,000 Reichsmarks for this.

Above all, they both had a passion for antiquity . Simon was the driving force behind the " German Orient Society ", which was founded in 1898 with the protection of the Emperor. In close cooperation with Wilhelm von Bode , the director of the Berlin museums, he ran the company and gave the money for many of its activities.

From 1911 onwards, Simon financed Ludwig Borchardt's excavations in Tell el-Amarna , Egypt , 300 km south of Cairo . Here was Pharaoh Akhenaten v to 1340th To build the new capital Achet-Aton for his revolutionary monotheistic sun state. The excavation campaign was extremely successful. The main pieces of the numerous finds were plaster stucco portrait heads of various members of Akhenaten's royal family and the unusually well-preserved painted bust of Nefertiti , his main wife, made of limestone. Since Simon was the sole financier and had signed a contract with the Egyptian government as a private person, the German portion of the finds passed into his personal possession.

The private collection

He had already developed his villa on Tiergartenstrasse into a private museum. In the Wilhelmine era, private art collections were seen as an opportunity to gain and demonstrate social importance - many so-called nouveau riche made use of this in the early years. Things were different with Simon. He started collecting art at an early age. He bought his first Rembrandt when he was 34 . After 1890, as a senior partner in the family company, he was able to use significantly larger amounts of money for his interest in art. It is more than likely that the intensive preoccupation with ancient art offered him a balance for what is often perceived as a monotonous job, a compensation for the unrealized desire to study the humanities.

Since the mid-1880s, Wilhelm von Bode had been Simon's advisor in building up a high-quality collection . Bode played a paramount role in the development of Berlin's museums. In addition, with his expert advice, he promoted the creation and targeted expansion of many Berlin private collections, also with the secondary idea that the public collections he directed could later benefit from donations from art-loving private individuals.

Simon was the first of the Berlin collectors to have decided to systematically collect not only one-sided pictures or sculptures , but also very different genres of art. The Italian Renaissance was at the center of his interests . Under the guidance of Bode, who advised him for a period of around 20 years, Simon assembled an extensive collection of paintings, sculptures, furniture and coins from the 15th to 17th centuries, which was also exemplary from the point of view of museum people. It could be viewed in the Villa Simon by appointment. Simon himself was immortalized in a painting by Ernst Oppler in 1904 , in which he can be seen in the middle of his collection.

Gifts

In 1900, Simon took the project of a new museum as an opportunity to donate his Renaissance collection to the state collections. In 1904 the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum (today's Bode-Museum ) was opened, a central concern for Bode for years, sponsored by the Kaiser as a Prussian prestige object. It was important to Simon to be involved in this company as a collector and Prussian patriot. His collection not only supplemented the existing holdings, it was also exhibited in a separate “Simon Cabinet”, and at Simon's request in a shared variety, very similar to what was previously in his private house. Bode also agreed that the various art categories could be combined to create a stylish and atmospheric overall impression. He designed the entire museum according to this principle. This same leitmotif of the art presentation is taken up again a good 100 years later, after years of renovation of the Bodemuseum and reopening in autumn 2006, albeit in a much weaker form as "Bode mild", as those responsible put it.

Immediately after parting with his Renaissance collection, Simon began building a second collection. Her focus was on German and Dutch wooden sculpture from the late Middle Ages , as well as historical furniture, tapestries, paintings and objects from the arts and crafts from Germany, France and Spain. This collection comprised about 350 pieces. Simon, who was very familiar with the Berlin museum landscape, had apparently put it together from the start in such a way that it complemented the existing holdings in a meaningful way. Immediately after the First World War he gave them to the Berlin museums. - For many years, Simon was also involved in the German Folklore Collection, the Berlin Coin Cabinet and the Egyptian and Near Eastern Department of the museums. Here, too, he donated carefully and systematically, depending on the situation in the individual museums.

After the Egyptian excavation campaign was completed in 1913, the bust of Nefertiti and the other finds from Tell el-Amarna also found a place in Simon's private collection, which also contained the important yew wood head of Queen Tiy , Akhenaten's mother, acquired in Cairo in 1905 . Numerous guests, above all Wilhelm II, admired the new attractions. Simon presented a first copy of Nefertiti to the emperor in October 1913. Soon afterwards, he donated a large part of his holdings to the Berlin museums, including in 1920 the now world-famous Egyptian finds. On his 80th birthday, Simon was honored with a large inscription in the Amarna Hall in the Neues Museum . His last public intervention was a letter to the Prussian minister of culture in which he advocated the return of the Nefertiti bust to Egypt.

In 1933, after the beginning of the anti-Semitic dictatorship of the National Socialists , the mentioned inscription was removed, as were all other references to his donations. Today a bronze bust and a plaque commemorate the patron. The text: “Dr. H. c. James Simon, Berlin 1851–1932, donated the excavations in Tell el-Amarna 1911–1914 to the German Orient Society and left the finds to the Egyptian Department in 1920 ”.

estate

His estate was auctioned off in 1932 by the Rudolph Lepke auction house in Berlin.

social commitment

In total, Simon gave away about a third of his annual income. Most of the time he did not support art or science, but social projects. These activities are only very incompletely documented because Simon did not care about their being known, but even avoided it whenever possible. A statement from him underlines this special attitude: "Gratitude is a burden that should not be placed on anyone" . After all, there is evidence that he founded numerous aid and charity associations, opened public baths for workers who otherwise could not afford a weekly bath, set up hospitals and built holiday homes on the Baltic Sea for workers' children, and helped destitute Eastern Jews to get a start in their new place of residence , wanted to bring good music and popular science knowledge to ordinary people in a “club for popular entertainment” - the list could be extended considerably. Simon also personally and directly supported a number of families in need, including young musicians and promising young scientists.

It is noticeable that Simon devoted his money and his commitment in this area exclusively to private facilities and institutions. He saw himself as a Prussian patriot, but primarily as a citizen, to whom his wealth also meant a social obligation. So he looked for approaches to develop impulses that could advance the community independently of government action.

Reviews and aftermath

The motives for Simon's social commitment were complex. In part, the fate of his daughter, who died early, will have prompted him to do so. In addition, his patronage was certainly based on Jewish traditions. Simon was not a very religious Jew, he did not take part in the activities of the Berlin Jewish community and did not visit the synagogue regularly . But obviously he was committed to the Jewish tradition of charity, which aims to help those in need so that they can help themselves. Other sources see as the main motive an unusually consistent "ideal of civic action", regardless of any religious affiliation.

The person of Simon is also seen in connection with a reassessment of the Wilhelmine era - or at least with a relativizing view of this time. After that, it would be all too one-sided to describe the imperial era with just the usual images: blatant social inequality, arrogant military, ostentatious bankers and industrialists, a cocky monarch with very limited personal skills. The pre-war empire was also the time when political parties developed, medicine and technology made enormous advances, and Berlin became a metropolis of culture and science. What made the city famous in the “ Roaring Twenties ” was at least laid out here. James Simon had his part in it.

On the initiative of the private circle of friends James Simon , in cooperation with the Baden-Württemberg State Representation, a memorial plaque was ceremoniously unveiled on the outside facade of the State Representation on June 16, 2006 in the presence of many of his descendants and representatives of the German Orient Society . Shortly before, on May 22, 2006, a memorial plaque was unveiled at the site of his last house at 23 Bundesallee in Berlin.

In May 2007, the District Assembly and the District Office in Mitte named the newly designed public green and recreational area on Burgstrasse James-Simon-Park . The park between the Stadtbahn viaduct and the Spree is located southwest of the Hackescher Markt S-Bahn station , and from there you have a direct view of the Museum Island. In 2012 the Stadtbad Mitte , which he donated, was given the nickname "James Simon".

The James-Simon-Galerie by David Chipperfield , opened in July 2019 in a ceremony by Chancellor Angela Merkel , is the central entrance building and visitor center of Berlin's Museum Island .

James Simon Foundation

The James Simon Foundation was founded in Berlin in 2006. Its aim is to remember James Simon as a patron in the social and cultural field.

Every two years, the James Simon Foundation therefore awards the James Simon Prize for exemplary social and cultural commitment in Germany. The prize is endowed with 25,000 euros. It was symbolically designed by the artist Johannes Grützke in the form of a medal with the portrait of James Simon. The foundation honors people who are exceptionally committed in a similar way to James Simon. The winners so far have been Werner Otto and Maren Otto (2008), Udo van Meeteren (2010), Carmen and Reinhold Würth (2012), Barbara Lambrecht-Schadeberg (2014), Wilhelm Winterstein (2016) and 2019 Christian Dräger .

literature

- Max Osborn : Dr. James Simon. For his 80th birthday on September 17th. In: Vossische Zeitung , No. 436, morning edition of September 16, 1931, first supplement / p. 5.

- Konrad Hahm : James Simon and German Folklore . In: Vossische Zeitung , No. 436, morning edition of September 16, 1931, first supplement / p. 5.

- Hans-Georg Wormit : James Simon as a patron of the Berlin museums . In: Yearbook of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation 2, 1963, pp. 191–199

- Ernst Feder : James Simon. Industrialist, art collector, philanthropist . In: Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 10, 1965, pp. 3-23

- Olaf Matthes: James Simon. Patron in the Wilhelmine era. Bostelmann & Siebenhaar (series Bürgerlichkeit, Wertewandel, Patronage , Vol. 5), Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-934189-25-3 .

- Peter-Klaus Schuster (Ed.): James Simon, collector and patron for the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, on the occasion of the 150th birthday of James Simon . Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-88609-190-2

- Bernd Schultz (Ed.): James Simon - Philanthropist and patron of the arts. Prestel, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-7913-3759-9 .

- Dietmar Strauch : James Simon. The man who made Nefertiti a Berliner . Progris, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-88777-018-1 . 2nd, extended edition, edition progris Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-88777-035-8 .

- Olaf Matthes: Simon, Henri James. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , pp. 436-438 ( digitized version ).

- Olaf Matthes: James Simon. The art of meaningful giving. Hentrich & Hentrich, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-942271-35-6 .

- Christian Schölzel: Imperial Jews. In: Dan Diner (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Jewish History and Culture (EJGK). Volume 3: He-Lu. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2012, ISBN 978-3-476-02503-6 , pp. 303-305.

- Olaf Matthes (Ed.): James Simon. Letters to Wilhelm Bode 1885–1927, Böhlau-Verlag, Vienna, Cologne, Weimar, 2019.

Movie

- The man who gave away Nefertiti. James Simon, the forgotten patron. Documentary and scenic documentation, Germany, 2012, 43:45 min., Script and direction: Carola Wedel , production: ZDF , 3sat , series: Jahrhundertprojekt Museumsinsel, first broadcast: December 8, 2012 on 3sat, summary ( memento from August 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) from ZDF with online video, memento, review by Andreas Kilb in the FAZ .

Web links

- Search for agent: "Simon, James" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Literature by and about James Simon in the catalog of the German National Library

- James Simon Foundation

- Ulrich Sewekow: Honor for the Jewish patron James Simon , Prometheus, Internet Bulletin for Art, News, Politics and Science. No. 109, July 2006

- Michael Zajonz: “The mansion as a museum space” , Tagesspiegel , October 18, 2006

- “He didn't care to be the center of attention” Deutschlandradio Kultur , June 19, 2006

- David Dambitsch: “Traded from Jewish tradition” - The art patron James Simon and his descendants. In: Schalom - Jüdisches Leben heute ( Memento from September 28, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) (MP3; 3.3 MB) on Deutschlandfunk, May 31, 2013, Memento.

Individual evidence

- ^ New German biography (NDB). Retrieved August 27, 2019 .

- ↑ Conversion of the James Simon house. Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung, August 24, 1909, accessed on September 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Fritz Monke, Rudolf Eschwe, Dorit Lehmann: The Tiergartenstraße - a piece of Berlin history , Berlin, 1975, pp 57-58, Figure 63-64..

- ^ Kai Drewes: Jüdischer Adel: Nobilitierungen von Juden in Europa des 19. Century. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 47.

- ↑ On the Orient Society and Simon's role as co-founder and driving force see Gernot Wilhelm (Ed.): Between Tigris and Nil. 100 years of excavations by the German Orient Society in the Middle East and Egypt , von Zabern, Mainz 1998, especially pp. 4–12.

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt: Portrait head of Queen Teje ; 18. Scientific publication of the German Orient Society, JC Hinrichs'sche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1911.

- ^ Andreas Kilb: Portrait of the patriot as a patron. FAZ v. December 8, 2012.

- ↑ Catalog 2059: Estate of Dr. James Simon, Berlin, [auction: Tuesday, November 29, 1932]; with a foreword by Max J. Friedländer , ( digitized version )

- ↑ For example, shown in Ulrich Sewekow: Late honor for James Simon. In: Alter Orient aktuell , issue 7, 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Commemorative plaque of the "Haus Kinderschutz", erected in 1906 in Berlin, Zehlendorf

- ↑ See Ulrich Sewekow: Late honor for James Simon. In: Alter Orient aktuell , issue 7, 2006, p. 11f.

- ↑ Press release No. 303/2007

- ↑ James Simon Foundation: Stadtbad Mitte - James Simon

- ↑ Nikolaus Bernau : A building for generations The James-Simon-Galerie is open . Berliner Zeitung , July 12, 2019; accessed on July 13, 2019.

- ↑ Preistraeger 2008 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. from the James Simon Foundation website, accessed May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Preistraeger 2010 on the James Simon Foundation website, accessed on May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Prize winner 2012 on the James Simon Foundation website, accessed on May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Prizewinner 2014 on the James Simon Foundation website, accessed on May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Preistraeger 2016 on the James Simon Foundation website, accessed on May 23, 2017.

- ↑ James Simon Prize for Dr. Christian Dräger. In: Lübeckische Blätter 184 (2019), pp. 90f

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Simon, James |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Simon, James Henry (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Entrepreneur of the imperial era and art patron |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 17, 1851 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Berlin |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 23, 1932 |

| Place of death | Berlin |