Rita Hayworth

Rita Hayworth [ ɹita heɪwɜːθ ] (born October 17, 1918 in New York City , New York ; † May 14, 1987 there ; actually Margarita Carmen Cansino ) was an American actress , dancer and film producer .

Rita Hayworth was discovered for the film in 1934 as her father's dance partner. In the course of her career she took part in 60 feature films until 1972. In the 1940s, when she celebrated her greatest successes, the actress, who was best known for her red-dyed hair, was given the nickname “The Love Goddess” (German: “The Goddess of Love”). Although she has also appeared in a number of hilarious film musicals , in which she was able to demonstrate her dancing talent alongside Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly , Hayworth was mostly fixed on the seductive femme fatale type because of her beauty and sensual charisma .

It was above all the title role in the cult film Gilda (1946) that had a lasting impact on her image as a screen goddess. An attempt to break with this role model with the film noir Die Lady von Shanghai (1948) failed. Later she tried again to free herself from the image of the glamorous film star and to switch to the character subject with productions such as the star-studded drama Separated from Table and Bed (1958). As a result of personal and health problems, however, it became difficult for her to establish herself as a character actress with increasing age.

In the 1970s she repeatedly made headlines when she was conspicuously forgetful at public appearances and behaved strangely, which at the time was attributed to excessive alcohol consumption. It was not until 1981 that Hayworth was diagnosed with the then little-known Alzheimer's disease as the real cause of their mental confusion, which attracted greater attention to the disease, especially in the United States.

In a 1999 American Film Institute poll , Hayworth was ranked 19th among the 25 greatest female film legends.

Life

Childhood and youth

Hayworth's father was the Spanish dancer Eduardo Cansino (1895–1968), who emigrated from Seville to the United States in 1913 . There he appeared with his older sister Elisa and other family members as “The Dancing Cansinos” in the vaudeville theaters popular at the time , where they caused a sensation, especially with flamenco . At a revue in New York in 1917, Eduardo met his future wife Volga Hayworth (1898–1945), who grew up in Washington, DC in an Irish - English family and tried her hand as a showgirl for the Ziegfeld Follies on Broadway . As Eduardo's and Volga's first child, Hayworth was born in 1918 in a hospital on New York's West Side and was baptized Margarita Carmen Cansino. Shortly after the birth, the family moved to Brooklyn from a Manhattan hotel for theater people . A year later, Hayworth's brother Eduardo Jr. was born. In 1922, Vernon, a third child, made it necessary to move to larger accommodation in Jackson Heights, a prosperous part of Queens .

At the age of four, Hayworth received her first dance lessons from her father, during which she used her first pair of castanets . When Eduardo and Elisa were on tour together, she was tutored by her uncle Angel Cansino. In a Vitaphone short film entitled La Fiesta (1926), Hayworth is said to have had her first screen appearance with “Dancing Cansinos”, even if it only lasted a few seconds. With film becoming more and more popular, and at the latest with the advent of sound films , the vaudeville theaters increasingly lost their importance. As a result, the family moved to Los Angeles in 1926 , where Eduardo promised a better financial future as a dance teacher and choreographer for Hollywood films .

After the global economic crisis in the late 1920s had resulted in fewer and fewer Americans being able to afford dance lessons and demand in Hollywood decreased, Eduardo Cansino was forced to close his dance school, which had been well attended until then, and to perform again as a dance duo with his sister . However, in 1931 she withdrew from show business in favor of her own family and moved back to Spain. After Hayworth first appeared on stage as a professional dancer at the age of 13 with her cousin Gabriel Cansino in support of a film screening of Back Street (1932), Eduardo decided to make his talented daughter his dance partner. The following three years they performed together as "The Dancing Cansinos" with various Spanish dances. Since Hayworth was too young by California law to work in licensed clubs, her appearances were limited to nightclubs in Tijuana just across the Mexican border and to pleasure boats off the coast of California. Hayworth, who first attended Alexander Hamilton High and later Carthay High School, also had to make up for the material that had been missed through appearances with additional homework.

The family eventually moved near the border in Chula Vista . Since Hayworth now had to do up to four or five shows in a day, Eduardo took his daughter out of school early and had her tutored by private tutors during her breaks. Hayworth, whose grandfather Antonio Cansino founded the family's dance tradition and had successfully built a dance school in Spain, later complained that her childhood consisted almost entirely of hard dance training, which is why she, unlike her brothers, had neither talent nor interest in dancing showed that it was hardly possible to make contact with people of the same age. In addition, both parents were very careful to keep their maturing daughter away from strange men in the casinos and nightclubs, which is why they hardly kept an eye on her and sometimes locked her in their cloakroom.

Beginnings in film

In a nightclub in Agua Caliente , which was particularly popular with film people as a resort with a horse racing track and bullfighting, the Cansinos finally got a month-long engagement. During one of her appearances, Rita Hayworth saw Winfield Sheehan , the head of production at Fox Film Corporation , who then invited her to Hollywood for a test shoot. Hayworth eventually got a contract with Fox and then took speaking and acting classes with other starlets from the studio. At the end of 1934 she made the drama The Ship of Satan , in which Spencer Tracy played the lead role and she appeared as a dancer, her first film. However, this was only released in cinemas in the fall of 1935, after Hayworth had already played small roles alongside Warner Baxter in The Whip of the Pampas (1935) and as an oriental servant in Charlie Chan in Egypt (1935) alongside Warner Oland, who was popular at the time played detective Charlie Chan was on screen.

She had her first major role in the musical Paddy O'Day , made that same year , in which, as a Russian immigrant Tamara Petrovitch , she helps a little orphan girl, played by Jane Withers , to find a new home. However, when the Fox Film Corporation merged with 20th Century Pictures to form 20th Century Fox , the head of the newly founded studio, Darryl F. Zanuck , no longer had any use for Hayworth and quickly terminated her contract. Her last appearance at Fox was in the film Dangerous Cargo (1936), which was about illegal immigration. After that, Hayworth was forced to stay afloat as a freelance actress for a while.

Starlet at Columbia Pictures

This was followed by a small role in the Columbia Pictures- produced crime film Meet Nero Wolfe (1936) and a number of small westerns from minor production companies: Lady of California (1936), Gun Smuggling in Louisiana (1937), Hit the Saddle (1937) and Carmen in Texas (1937), in which she played the leading female role. Her first husband, Edward C. Judson, who managed her at the time, finally helped her get a seven-year contract with Columbia Pictures. So far, Hayworth has appeared as an actress under the name Rita Cansino. Columbia's studio boss Harry Cohn didn't like the name Cansino, however. So it was quickly changed - after the maiden name of her mother - to "Hayworth". In Criminals of the Air (1937), her first film under her new contract, she was cast as a Mexican dancer, as was the case with Fox or in her westerns. She then appeared in countless crime films from Columbia's B-film department, in which she no longer played exotic beauties, but rather ambitious young American women. Charles Quigley was her screen partner particularly often , for example in the films Girls Can Play , The Game That Kills or The Shadow , published in 1937 , which were set in the sports and circus milieu. But unlike Quigley's career, Hayworths soon went uphill. Under the direction of "women director" tried George Cukor , she was tested for a role in the Columbia-produced screwball comedy The Bride's Sister (1938), in which she was tested alongside Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant Hepburn's materialistic sister should play. During a test with Hepburn, however, Cukor felt that Hayworth was too young and inexperienced for the role, and eventually gave it to Doris Nolan while he promised Hayworth that he would later cast it in another film.

After other minor crime films such as Homicide Bureau (1939), in which she played a forensic scientist , unusual for the time, and the George O'Brien Western The Renegade Ranger (1938), for which she was loaned to RKO Pictures , appeared she first appeared in the crime comedy The Lone Wolf Spy Hunt (1939) alongside Warren William and Ida Lupino as a seductive female character, who anticipated her later roles as femme fatale . For this role, Hayworth received for the first time in her career specially designed costumes and a light double .

However, it was her appearance in the Columbia blockbuster aviator film SOS Fire on Board (1939) directed by Howard Hawks that gave Hayworth's career the decisive impetus. The male lead played Cary Grant. Grant played the rough boss of an airline that carries mail across the Andes . Hayworth played his former girlfriend who turned him into a misogynistic cynic who only opens up to love again through a showgirl, played by Columbia's then star Jean Arthur . Both audiences and critics reacted very positively to Hayworth, so Columbia decided to build Hayworth, who continued to take acting classes, through large-scale PR campaigns as the studio's new star. In addition to filming, Hayworth now spent more time than ever on photo shoots in glamorous and pin-up poses.

However, Columbia struggled to find suitable projects for the actress. In the little-known film musical Music in My Heart (1940), Hayworth's dancing talent at the side of Tony Martin was hardly challenged. George Cukor finally kept his promise and loaned it to Columbia for the high-quality MGM production Susan und der liebe Gott (1940). Hayworth was used alongside Joan Crawford and Fredric March in the role of a fickle young actress. As a result, Hayworth received lucrative role offers from other studios and producers such as Cecil B. DeMille . But first of all, Hayworth shot the film drama The Lady in Question (1940) in the role of a young woman innocently accused of murder, her first of five films together with Glenn Ford . The remake of a French film starring Michèle Morgan was directed by Charles Vidor , who was to turn four films with Hayworth. Hayworth then starred as a naive, job-seeking showgirl alongside Douglas Fairbanks Jr. in Angels Over Broadway (1940), directed by Ben Hecht , who is best known as a screenwriter .

Breakthrough in Hollywood

Hayworth owed her final breakthrough to two loan-outs . For the nostalgic comedy Most Beautiful in Town (1941), Hayworth was loaned by Warner Brothers after Ann Sheridan had turned down the title role. At the side of James Cagney and Olivia de Havilland and under the direction of the experienced director Raoul Walsh , Hayworth embodied the beautiful Virginia Brush, who attracts the looks of all men and that of, in the film set in New York at the turn of the century Cagney played dentist Biff Grimes later on losing to his best friend. Although the film was shot in black and white , given the original title, The Strawberry Blonde , there was an insistence on dyeing Hayworth's dark brown hair auburn for the first time in her career. Jack L. Warner was so taken with Hayworth's performance that he promptly re-loaned it for the screwball comedy Affectionately Yours , with Hayworth's name first appearing above the title on movie posters. The film turned out to be a flop, but it didn't hurt Hayworth's career.

It was the role of Doña Sol in the bullfighting drama King of the Toreros (1941) that catapulted Hayworth into Hollywood's A-League. 20th Century Fox took a long time to find the right cast and tested a variety of actresses, including Maria Montez , Gene Tierney , Lynn Bari and Dorothy Lamour , for the role. The director of the film, Rouben Mamoulian , finally insisted on giving Hayworth, then 22 years old, the role of Spanish femme fatale because of her sensual charisma and her cat-like way of moving. The film, which was to be Hayworth's first color film , is based on a novel by Vicente Blasco Ibáñez , which was successfully filmed in a silent film version with Rudolph Valentino in 1922 . The role of Doña Sol, who seduces the bullfighter Juan Gallardo, played by Tyrone Power , drives him into the abyss and then drops it for a younger one, made Hayworth the most sought-after actress overnight.

A year later she made two more films for 20th Century Fox: the star-studded episode film Six Fates , in which, as a married woman, she embarks on a fateful affair with Charles Boyer , and the technicolor musical The Queen of Broadway , in which she plays the Took the title role at the side of Victor Mature , after she had already proven her talent in this genre with Columbia with the film musical Reich you will never (1941).

Success in the film musical

You will never get rich was the first of two films together with Fred Astaire , which was to revive Astaire's career after the temporary end of his collaboration with Ginger Rogers and to establish Hayworth in the genre. Astaire played a dance director in the film who was drafted into the military and fell in love with Hayworth. Cole Porter contributed the music . Shortly after filming, Life magazine published Hayworth's famous pin-up photo on August 11, 1941, which, along with a picture of actress Betty Grable, became the most popular pin-up of American GIs during World War II .

In 1942, Hayworth's second musical with Astaire, Duke were never more enchanting , offered the audience escapism with its fairytale story set in Argentina and was just as successful as its predecessor. Hayworth was now Columbia's biggest star, which is why studio boss Harry Cohn decided that she could no longer be loaned to other studios in the future and, like Greta Garbo , should only make one film per year in order not to oversaturate the audience.

Off the screen, Hayworth, whose brothers were stationed as soldiers in the Pacific and Europe during World War II , like many other stars of their day, was busy giving moral support to the country in wartime. She promoted war bonds , appeared on radio shows directed at the soldiers, and dined and danced with GIs in the legendary Hollywood Canteen . With her future husband, the director Orson Welles , who is known as a child prodigy and genius , she also appeared in magic shows for the soldiers and allowed herself to be divided into two halves.

In May 1943, filming began for Columbia's biggest project of the year. In the lavish Technicolor musical Es tanzt die Göttin (1944), Hayworth appeared - again under the direction of Charles Vidor - as a showgirl who, because of her pretty face, makes a career, but is not happy, and in the end returns to the man who it loves. Hayworth's screen partner was Gene Kelly , who was loaned by MGM and was also responsible for the choreography. The film became a great success with the public and the critics were also full of praise, as it represented a further development of the genre through innovative trick technology and with music and dance interludes as important parts of the plot. The film marked the breakthrough for Gene Kelly, while further cementing Hayworth's front row position in Hollywood. At the beginning of 1945 another profitable musical followed with Tonight and Every Night . This time Hayworth played a showgirl in war-torn London who fell in love with a US pilot and was on stage every evening despite the bombing. As in all of her films, however, Rita Hayworth did not sing herself. In her songs she was always dubbed by singers such as Nan Wynn, Martha Mears, Anita Ellis and Jo Ann Greer.

Rise to superstar

While light, colorful musicals were in demand during the war, after the end of the war film noir flourished with its pessimistic and disillusioning worldviews. In September 1945 filming began on Gilda , a melodrama set in South America with a heavily charged erotic subtext, in which Hayworth played the title role. Her screen partner was Glenn Ford, with whom she had already shot The Lady in Question . The direction was again directed by Charles Vidor. The role of the provocative Gilda, who turns men’s heads and falls in love-hate relationship with Ford’s Johnny Farrell, marks the most famous screen appearance in Hayworth’s career. As an erotic classic of the "Black Series" , the film is particularly famous for the scene in which Hayworth takes off her long black gloves in a strapless black satin dress to the song Put the Blame on Mame . Although the reviews were bad at the time, audiences flocked to cinemas worldwide in droves. Bosley Crowther , the feared New York Times critic , called Hayworth a "superstar" after seeing her in Gilda .

After Gilda's immense success , Hayworth was at the height of her fame as a screen goddess. It therefore made sense for Columbia to cast her in her next film as Terpsichore , who comes to earth as the divine muse of dance in order to re-stage a Broadway show that is unacceptable to her. With Down to Earth (1947) the last typical Hayworth musical that became known as one of the most expensive productions in Columbia's Studio story originated. After the film was released, Life magazine proclaimed Hayworth the "American goddess of love" and devoted an extensive editorial to her and the film.

The Hayworth cult was suddenly shaken when Hayworth made the film noir The Lady of Shanghai (1947) with her then husband Orson Welles . Hayworth played the married Elsa Bannister, who entangled the welles-played sailor Michael O'Hara in a web of intrigue and did not shrink from murder. To the horror of Harry Cohn and her fans, Hayworth appeared in the role of the cold, calculating femme fatale with a short blonde hairstyle, with which the actress tried in vain to break away from her Gilda image in order to be perceived as a serious actress in the future. But neither the critics nor the audience accepted a blonde and evil Hayworth. The film also turned out to be a big flop due to high production costs. Only years after its premiere did The Lady of Shanghai become a classic of its genre. The final scene in the cabinet of mirrors has become particularly famous .

In order to build on the old successes turned Hayworth, regrown their hair after several months of travel through Europe and was colored red again, with Glenn Ford love nights in Seville (1948), a film adaptation of Prosper Mérimée 's famous Carmen - amendment and Hayworth last collaboration with Charles Vidor . At the same time, it was the first film to be co-produced by Hayworth's recently founded production company, the Beckworth Corporation, which gave Hayworth both a say and a 25% share in the profits. While Glenn Ford is generally considered miscast in the role of Don José, Hayworth was able to convince most of the critics as a man-devouring Carmen despite Hollywood presentation. By the time the film came out and was easily recovering its budget, Hayworth was one of the highest paid and most valuable actresses in the world.

Film breaks and comebacks

1948-1953

After her separation from Orson Welles and the exhausting filming of Love Nights in Seville , Hayworth decided in May 1948 to take a vacation for several months until her next film. In New York, she first saw the latest theater plays before traveling on to Paris . Although she returned to Hollywood briefly to take part in the initial preparations for her next planned film, the Western Lorna Hanson , she did not stay long and traveled to Europe again. The film she was supposed to make with William Holden and Randolph Scott was ultimately never realized. As a result, the actress fell out of favor with Columbia and was suspended. Hayworth was meanwhile on the Côte d'Azur , where the international jet set was bustling and, in addition to countless playboys , the young Shah of Persia vied for their attention. At a party given by Elsa Maxwell in Cannes , Hayworth met Prince Aly Khan in early July 1948 . Since both were separated from their respective spouses at the time, but not officially divorced, their romance and subsequent wedding, which was accompanied by papperazzi everywhere, made headlines in the international tabloid press as big as Ingrid Bergman's scandalous connection with Roberto Rossellini .

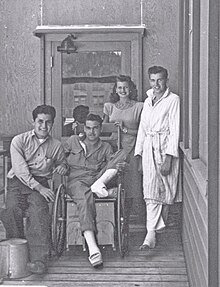

After the breakdown of her tumultuous marriage to Khan, Hayworth returned to Hollywood in 1951. It had been three years since her last screen appearance. The only result was Champagne Safari (1951), a 60-minute documentary about the second honeymoon with Aly Khan, which shows the couple in southern Europe and various African countries shortly before their separation. After the return of its still greatest star, Columbia Pictures immediately lifted Hayworth's suspension and tried to get a new project off the ground for them as quickly as possible. However, it was nine more months before filming of the crime film Affair in Trinidad (1952) began, which, due to the cast of Glenn Ford, was an obvious copy of Gilda to critics and audience , but which - thanks also to targeted advertising campaigns from Columbia - an even greater financial success was when the 1946 film and Hayworth made a successful comeback with it .

Hayworth then turned on the side of Stewart Granger and Charles Laughton, the also grossing Bible adaptation Salome (1953), in which she played the eponymous biblical princess. In view of the heavily falsified Bible history , the monumental film directed by William Dieterle was only able to convince the critics with Hayworth's dance of the seven veils , which was influenced by modern dance . This was followed by the 3D method produced Somerset Maugham film version Purgatory (1953) with Hayworth in the role of frivolous Sadie Thompson, which meets on a South Sea island on a religious zealot. The story, heavily censored due to the Hays Code in the film, had previously been filmed with Gloria Swanson (1928) and Joan Crawford (1932) and gave Hayworth the opportunity to prove that she was not only a movie star but also an actress, which is why she also insisted on protests from Harry Cohn to be less glamorous in the film. She received good reviews for her portrayal of a woman with a past, and Somerset Maugham also praised her performance, but the audience was less enthusiastic.

1954-1957

Due to her fourth marriage to the singer Dick Haymes , which was marked by trouble with state authorities and legal battles with Columbia over the failed Joseph and His Brethren project , Hayworth put another multi-year film break. In the meantime, she has been increasingly supplanted on screen and in the public eye by younger actresses such as Ava Gardner , Marilyn Monroe , Grace Kelly and Elizabeth Taylor . When asked about this, Hayworth is said to have said of her successors with relief: “You can make the headlines, I've had enough! The only headlines I want are about my acting skills. "

With the Caribbean- based adventure film Game with Fire , in which Jack Lemmon and Robert Mitchum vie for their favor, Hayworth returned to the big screen in 1957 after Ava Gardner had rejected the female lead in the film. Hayworth's second comeback in the role of a more mature, life-battered but still beautiful woman was not nearly as successful as the one in 1952, which was also due to the final cut of Columbia, which completely overturned the original concept of the film threw. In the same year Hayworth was seen for the last time in a film musical with Pal Joey , a screen adaptation of the Broadway hit of the same name . Directed by George Sidney , she played an elderly, wealthy widow who ultimately loses the singer Joey , who she sponsored and played by Frank Sinatra , to her younger rival, who was played by Columbia's new star Kim Novak . Pal Joey was a huge box office hit and would be Hayworth's last film under her 20-year contract with Columbia Pictures.

Serious character roles and final films

1958–1962

No longer under contract with Columbia, Rita Hayworth was active as a freelance actress until the end of her career. In search of roles that should help her to finally leave the image of the sensual Gilda behind at almost 40 and switch to the longed for character subject , her future fifth husband James Hill helped her . As a co-owner of the production company Hecht-Hill-Lancaster, he got her the role of Ann Shankland in the star-studded ensemble film Separated from Table and Bed (1958), which is based on a play by Terence Rattigan . At the side of Burt Lancaster , David Niven , Deborah Kerr and Wendy Hiller and under the direction of the talented young director Delbert Mann , Hayworth played a former photo model who struggles with aging and wants to win back her ex-husband out of loneliness. The film received excellent reviews and seven Oscar nominations and was also one of the most successful productions of the year. Hayworth also received critical acclaim for her portrayal of Ann Shankland. Nevertheless, at this point she considered retiring from the film business. James Hill, who was now convinced of her talent as a serious actress, persuaded her to continue making films.

In the western They came to Cordura (1959) directed by Robert Rossen , she then played the only female role alongside Gary Cooper , Van Heflin and Tab Hunter and returned to Columbia for the last time. As a prisoner accompanying a cowardly major and a group of soldiers through the Mexican desert, Hayworth renounced all glamor and let himself be made up older. As a result, she received some of the best reviews of her career for her acting performance. However, the film failed the audience. That same year, the court drama Sensation followed on page 1 , in which she was shown for the first time as a mother in the role of a lower-middle-class woman accused of the murder of her husband. It was directed by the famous playwright Clifford Odets , who also wrote the script and had long wanted to work with Hayworth. Once again, the critics were full of praise for Hayworth, but this time too there was no box office success.

Hayworth and James Hill eventually started their own small production company called Hillworth. After Hayworth had already co-produced Love Nights in Seville , Affair in Trinidad and Salome with her Beckworth Corporation , she now appeared again as a film producer in the rogue comedy Rendezvous in Madrid (1962) and was mentioned for the first time in the opening credits. The film, in which Hayworth and Rex Harrison as a crook couple want to steal a painting from the Prado , turned out to be a big flop. The already troubled marriage between Hayworth and Hill was soon divorced. Together with Gary Merrill , with whom she then had a relationship, Hayworth was to make her theatrical debut on Broadway in 1962 in the play Step on a Crack . However, after the first week of rehearsals, Hayworth was on sick leave due to nervous exhaustion and was eventually replaced by another actress.

1963-1972

After several months without role offers, Hayworth was cast in 1963 as a replacement for Lilli Palmer in the film drama Circus World (1964) alongside John Wayne in the role of a former high wire artist and as the mother of Claudia Cardinale . The delayed filming proved difficult and Hayworth was increasingly being said to have a drinking problem. For her portrayal of Lili Alfredo, however, she was nominated for the Golden Globe in the category Best Actress - Drama in 1965 and thus received a nomination for a prestigious film award for the first and only time in her career. In the crime film Goldfalle (1965) she was then seen in her fifth and last joint film with Glenn Ford. While the film was otherwise panned, Hayworth stood out to the critics as the seedy waitress and old love of Ford's acted cop. Time found Hayworth "at 47 [looked] never less like a beauty but never as much as an actress."

This was followed by productions that, like Rendezvous in Madrid and Circus-Welt , were shot primarily in Europe, including two films by James Bond director Terence Young : the UN co-produced anti-drug film Poppy is Also a Flower (1966), in which Hayworth to a number of international stars such as Yul Brynner , Omar Sharif and Marcello Mastroianni was one, and the the time of Napoleon playing adventure film I come from the end of the world (1967), in which it after King of the Toreros a second time next to Anthony Quinn used came. A year later she was in the cynical gangster film The Bastard as the alcoholic mother of Giuliano Gemma and Klaus Kinski , who was originally supposed to play Joan Crawford.

As an emotionally disturbed mother in the Lanzarote film drama The Road to Salina (1970), Hayworth again delivered a strong performance in her early 50s, prompting the Los Angeles Times to write that it was “the irony of Rita Hayworth's career”, “that she makes fewer (and increasingly obscure) films, but always provides better ideas ”. After the release of the low-budget production The Naked Zoo (1971), which had been shot in 1966 and marked the low point in Hayworth's career as a cheap exploitation film with fans and critics, she made her last screen appearance in 1972 in the western To the Devil with Hosianna . As partner of Robert Mitchum, who played a smoking and shooting priest, she embodied the deeply religious mother of a mad criminal.

Alzheimer's Disease and Last Years of Life

At the age of 43, Rita Hayworth began to show signs of Alzheimer's disease . By the early 1970s, her health had deteriorated so much that she could no longer take on any other roles. In July 1981 she was incapacitated. Her daughter from her marriage to Prince Aly Khan, Yasmin Aga Khan , took her to New York and looked after her until her death in 1987. Hayworth, who died at the age of 68, was born in Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City , California, buried.

Yasmin Aga Khan still remembers her mother through her annual "Rita Hayworth Galas" in New York and Chicago and collects money for research into Alzheimer's disease through donations from the New York high society.

Private life

Rita Hayworth was married a total of five times and had two daughters. In 1937 she married Edward C. Judson, a businessman 20 years her senior, who managed her and drove her career. The marriage was divorced in May 1942. After a romance with Victor Mature , Hayworth married Orson Welles in September 1943 , with whom they had a daughter, Rebecca Welles (1944-2004). After a first separation in autumn 1945 and several attempts at reconciliation, the divorce followed in December 1948.

In May 1949, Hayworth, who was raised a Catholic, and Prince Aly Khan , known as Playboy , who was the son of Aga Khan III. Muslim faith was married by the communist mayor of Vallauris near Cannes , with great attention from the press and world public . A marriage according to the Islamic rite took place one day after the civil ceremony. At the end of December 1949, their daughter, Princess Yasmin Aga Khan, was born. The couple separated in 1951; however, the divorce did not take place until January 1953.

In September 1953, Hayworth married the Argentine singer Dick Haymes, who was popular in the United States . However, the marriage ended in divorce in December 1955 after only two years. In February 1958, Hayworth was married to the film producer James Hill for the fifth and last time, but it also ended in divorce in September 1961. Despite her five marriages and her artistic reputation as a goddess of love, Hayworth was considered very reserved in private.

After-effects in literature, film and pop culture

In Manuel Puig's first novel, Betrayed by Rita Hayworth (original title: La traición de Rita Hayworth , 1968), which immediately became a classic of Argentine literature, Puig refers to Hayworth's role of Dona Sol in King of the Toreros (1941), which like in the film, the protagonist of the novel is also fatal as a femme fatale .

The film drama The Barefoot Countess (1954) with Ava Gardner in the role of a Spanish dancer who becomes a celebrated Hollywood star and marries a nobleman is based in part on Hayworth's life. Originally, Hayworth was even intended for the title role, which she turned down because of the parallels to her own biography. Decades later, Hayworth served alongside Veronica Lake and Lauren Bacall as the inspiration for the cartoon character Jessica Rabbit, portrayed as a femme fatale, in Wrong Game with Roger Rabbit (1988).

In the prison film The Condemned (1994), based on the Stephen King novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption , inmates in the prison cinema prefer to watch the film Gilda . A pin-up poster by Rita Hayworth then becomes a symbol of the redemption of the protagonist, played by Tim Robbins , by hiding an escape tunnel behind it. Hayworth was also paid tribute in other films, particularly in the role of Gilda. In David Lynch's Mulholland Drive (2001), an amnesiac woman calls herself "Rita" after reading Hayworth's name on a Gilda poster, and becomes a femme fatale as the film progresses.

In Notting Hill (1999), Julia Roberts played a famous actress who at one point spoke to Hayworth with the words “They go to bed with Gilda, they wake up with me.” (Eng: “You go to bed with Gilda, you wake up” up with me. ”) and thus alludes to her image and its effects on her love life. In the French crime comedy 8 Women (2002), Fanny Ardant's vocal performance is based on Hayworth's glove striptease in Gilda . Isabelle Huppert , initially inconspicuous in the same film , later wears her red hair like Hayworth and a strapless robe with a large bow, which also refers to Gilda or Hayworth.

In Michael Jackson's This Is It (2009) Hayworth can be seen in a video for the song Smooth Criminal , in which Michael Jackson catches a glove by assembling it, which Hayworth throws into the audience in the role of Gilda. Hayworth is also one of the many legendary Hollywood icons mentioned in Madonna's song Vogue ("Rita Hayworth gave good face"). In June 2005 the album Get Behind Me Satan by the rock band The White Stripes was released , on which at least two songs refer to Hayworth. The song Take, Take, Take tells how a fan in a bar successfully asks Hayworth for an autograph and photo, but is disappointed in his insatiability when the actress leaves the bar without a kiss or even a lock of her to give her hair. White Moon, on the other hand, describes an unfulfilled longing for a pin-up named Rita, who is an unreachable “ghost”. The band's singer and guitarist, Jack White , said Hayworth was his source of inspiration when writing the songs for the album. White also owns a guitar with a portrait of the actress on the back, which he uses for his appearances with the White Stripes.

Filmography

- 1934: Cruz Diablo (appearance not confirmed)

- 1935: The whip of the Pampas (Under the Pampas Moon)

- 1935: Charlie Chan in Egypt (Charlie Chan in Egypt)

- 1935: The Ship of Satan (Dante's Inferno)

- 1935: Paddy O'Day

- 1936: Dangerous cargo (human cargo)

- 1936: Meet Nero Wolfe

- 1936: Lady of California (Rebellion)

- 1937: Gun smuggling in Louisiana (Old Louisiana)

- 1937: Hit the Saddle

- 1937: Carmen in Texas (Trouble in Texas)

- 1937: Criminals of the Air

- 1937: Girls Can Play

- 1937: The Game That Kills

- 1937: Paid to Dance

- 1937: The Shadow

- 1938: Who Killed Gail Preston?

- 1938: Special Inspector

- 1938: There's Always a Woman

- 1938: Convicted

- 1938: Juvenile Court

- 1938: The Renegade Ranger

- 1939: Homicide Bureau

- 1939: The Lone Wolf Spy Hunt

- 1939: SOS fire on board (Only Angels Have Wings)

- 1940: Music in My Heart

- 1940: Blondie on a Budget

- 1940: Susan and God (Susan and God)

- 1940: The Lady in Question

- 1940: Angels Over Broadway

- 1941: Most Beautiful in Town (The Strawberry Blonde)

- 1941: The Heartbreaker (Affectionately Yours)

- 1941: King of the Toreros (Blood and Sand)

- 1941: Empire you'll never (You'll Never Get Rich)

- 1942: Six Fates (Tales of Manhattan)

- 1942: The Queen of Broadway (My Gal Sal)

- 1942: You were never captivating (You Were Never Lovelier)

- 1944: The Goddess Dances (Cover Girl)

- 1945: Tonight and Every Night

- 1946: Gilda

- 1947: A goddess on earth (Down to Earth)

- 1947: The Lady from Shanghai (The Lady from Shanghai)

- 1948: Love nights in Seville (The Loves of Carmen)

- 1952: Affair in Trinidad (Affair in Trinidad)

- 1953: Salome

- 1953: Purgatory (Miss Sadie Thompson)

- 1957: Playing with Fire (Fire Down Below)

- 1957: Pal Joey

- 1958: Separated from table and bed (separate tables)

- 1959: They came to Cordura (They Came to Cordura)

- 1959: Sensation on page 1 (The Story on Page One)

- 1962: Rendezvous in Madrid (The Happy Thieves)

- 1964: Circus World (Circus World)

- 1965: Gold Trap (The Money Trap)

- 1966: The Poppy Is Also a Flower (The Poppy Is Also a Flower)

- 1967: I come from the end of the world (L'avventuriero)

- 1968: The Bastard (I bastardi)

- 1970: The road to Salina (La Route de Salina)

- 1971: The Naked Zoo

- 1972: To hell with Hosanna (The Wrath of God)

German dubbing voices

The actresses who voiced Rita Hayworth in the German dubbed versions include:

- Monika Rasky - Charlie Chan in Egypt

- Gisela Breiderhoff - SOS fire on board

- Carin C. Tietze - Susan and God

- Dagmar Heller - the most beautiful in town

- Viktoria Brams - Empire you'll never , you were never bewitching , Gilda (second dubbed version of 1979)

- Til Klokow - King of the Toreros , Gilda (1st dubbed version from 1949), The Lady of Shanghai

- Ilse Werner - The Queen from Broadway

- Eleonore Noelle - The goddess is dancing , Salome , I come from the end of the world

- Viola Sauer - Affair in Trinidad

- Gisela Trowe - purgatory , playing with fire , Pal Joey , you came to Cordura , sensation on page 1

- Tilly Lauenstein - Separated from table and bed , rendezvous in Madrid , circus world , Goldfalle , The Bastard , To the devil with Hosanna

- Inge Langen - Poppy is also a flower

- Ursula Traun - The road to Salina

Radio appearances (selection)

Rita Hayworth worked from 1939 to 1948 in a number of US radio play productions and radio shows .

- 1939: The Lux Radio Theater (episode Only Angels Have Wings from May 29, 1939)

- 1940: The Gulf Screen Guild Theater (episode Elmer the Great, April 14, 1940)

- 1941: The Eddie Cantor Show (episode It's Time to Smile January 8, 1941)

- 1941: The Lux Radio Theater (episode Remember the Night of December 22, 1941)

- 1941: The Mercury Theater (episode There Are Frenchmen and Frenchmen of December 29, 1941)

- 1942: The Lux Radio Theater (episode The Strawberry Blonde of March 23, 1942)

- 1942: The Lux Radio Theater (episode Test Pilot from May 25, 1942)

- 1942: Command Performance ( Followed by Rita Hayworth October 27, 1942)

- 1942: The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show (Follow Gracie's Dating Service December 29, 1942)

- 1943: The Bob Hope Show (episode From Palm Springs January 5, 1943)

- 1943: Command Performance ( Followed by Rita Hayworth from February 6, 1943)

- 1943: The Lux Radio Theater (episode The Lady Has Plans of April 26, 1943)

- 1944: The George Burns and Gracie Allen Show (episode of Keeping Rita Company of March 21, 1944)

- 1944: The Lux Radio Theater (episode Break of Hearts from September 11, 1944)

- 1945: The Charlie McCarthy Show (Follow The Auction of April 22, 1945)

- 1945: The Jack Benny Show (episode From San Francisco of May 20, 1945)

- 1945: Command Performance ( Followed by Rita Hayworth from May 31, 1945)

- 1945: GI Journal (episode of July 13, 1945)

- 1945: The Tommy Dorsey Show (episode Rita Hayworth July 15, 1945)

- 1945: Command Performance (Follow Walter O'Keefe from August 9, 1945)

- 1945: Command Performance (episode Victory Extra from August 15, 1945)

- 1946: The Charlie McCarthy Show (episode Going to Dinner January 20, 1946)

- 1946: The Lux Radio Theater (episode This Love of Ours February 4, 1946)

- 1946: The Alan Young Show (episode of Smashed Fender February 8, 1946)

- 1946: The Alan Young Show (Followed by Alan Visits Rita Hayworth on February 15, 1946)

- 1946: Suspense (episode Three Times Murder of October 3, 1946)

- 1948: Command Performance (Followed by the Sixth Anniversary Program of May 29, 1948)

- 1948: The Woodbury Journal (episode October 17, 1948)

TV appearances as guest star (selection)

- 1953: Toast of the Town (aka The Ed Sullivan Show with Ed Sullivan , episode March 22, 1953)

- 1971: The Carol Burnett Show (with Carol Burnett , episode February 1, 1971)

- 1971: The Merv Griffin Show (with Merv Griffin , episode of Jul 12, 1971)

- 1971: The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson (with Johnny Carson , episode August 4, 1971)

- 1971: Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In (episode September 27, 1971)

- 1973: This Is Your Life (episode Glenn Ford February 18, 1973)

- 1973: VIP swing (with Margret Dünser , episode from November 28, 1973)

- 1976: The Russell Harty Show (episode January 23, 1976)

Awards

- 1965: Nomination for the Golden Globe in the category Best Actress - Drama for Circus World

- 1977: National Screen Heritage Award for Lifetime Achievement

- 1978: Valentino d'Oro for life's work

- 1978: Miss Wonderful Award for Lifetime Achievement

- 2009: AFI Dallas Star Award for Lifetime Achievement (posthumous)

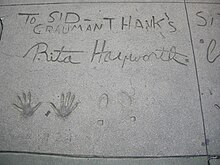

- Star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame (1645 Vine Street)

literature

Biographies

- John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, ISBN 0-393-07526-5 .

- Joe Morella, Edward Z. Epstein: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Delacorte Press, New York 1983, ISBN 0-385-29265-1 .

- Christian Dureau: Rita Hayworth . Pac, Paris 1985, ISBN 2-85336-260-4 .

Rita Hayworth's films

- Gerald Peary: Rita Hayworth. Your films, your life . Heyne, Munich 1981, ISBN 3-453-86031-4 .

- Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, ISBN 0-8065-0439-0 .

Illustrated book

- Caren Roberts-Frenzel: Rita Hayworth. A Photographic Retrospective . Abrams, New York 2001, ISBN 0-8109-1434-4 .

Further literature

- James Hill : Rita Hayworth. A memoir . Robson, 1983, ISBN 0-671-43273-7 .

- Speaking of Rita Hayworth . With an essay by Marli Feldvoss. New Critique Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-8015-0301-1 .

- Adrienne L. MacLean: Being Rita Hayworth. Labor, Identity and Hollywood Stardom . Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick 2004, ISBN 0-8135-3389-9 .

- Neil Grant: Rita Hayworth in Her Own Words . Hamlyn, London 1992, ISBN 0-600-57459-8 .

- Adolf Heinzlmeier : Rita Hayworth. Cover girl. In: Adolf Heinzlmeier, Berndt Schulz and Karsten Witte: The immortals of the cinema. The glamor and myth of the stars of the 40s and 50s . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1980, ISBN 3-596-23658-4 , pp. 91-96.

Film documentaries

- Champagne safari . Film about the second honeymoon of Rita Hayworth and Aly Khan, director: Jackson Leighter, USA 1951, 60 minutes.

- Hollywood and the Stars: The Odyssey of Rita Hayworth . Director: Al Ramrus, USA 1964, Wolper Productions, 30 minutes.

- Rita Hayworth: Dancing Into the Dream . Director: Arthur Barron, USA 1990, King Arthur Productions, 60 minutes.

- Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth . Director: Laurent Preyale, France 2000, Striana Productions, 26 minutes.

- Rita . Director: Elaina Archer, USA 2003, Turner Classic Movies, 59 minutes.

Web links

- Rita Hayworth in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Literature by and about Rita Hayworth in the catalog of the German National Library

- Pictures by Rita Hayworth In: Virtual History

- Rita Hayworth at Turner Classic Movies (English)

- Rita Hayworth in the database of Find a Grave (English)

- Obituary in the New York Times , May 16, 1987 (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Barron H. Lerner: When Illness Goes Public: Celebrity Patients and How We Look at Medicine . The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1st Edition, 2006, pp. 174-179.

- ↑ cf. official website of the American Film Institute

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 18, 25-26.

- ^ Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, p. 14.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 29.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 35.

- ^ A b c John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 41-43.

- ^ A b c John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 47-49.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 20-21.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 71-73.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 78.

- ↑ a b c d e John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 91-95.

- ↑ Joe Morella, Edward Z. Epstein: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Delacorte Press, New York 1983, p. 39.

- ^ Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, p. 100.

- ^ A b John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 102-104.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 106/293.

- ↑ a b c d John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 111-115.

- ^ Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, p. 123.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 123.

- ^ A b John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 129-133.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 147/152.

- ^ A b John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 153-155.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 145.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 166.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 184.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 135-136.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 190-194.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 197.

- Jump up ↑ Bosley Crowther : Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford Stars of 'Gilda' at Music Hall . In: The New York Times , March 15, 1946.

- ^ A b John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 201-205.

- ^ Winthrop Sargeant : The Cult of the Love Goddess in America . In: Life , November 10, 1947, pp. 81-96.

- ^ A b John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 210-214.

- ^ David Thomson : Rosebud. The Story of Orson Welles . Abacus, London 2005, p. 280.

- ^ Bernard F. Dick: The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row. Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures . University Press of Kentucky, 1993, p. 139.

- ↑ a b c d John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 223-228.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 252.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 14/237.

- ^ A b John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 230-235.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 271-272.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 284-287.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 292-299.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 300-305.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 289-291, 297.

- ↑ “They can have the headlines, I've had enough! The only headlines I want are on my acting. " Quoted from John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, p. 291.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 305-309.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. The Time, The Place and the Woman . W. W. Norton, New York 1977, pp. 311-313.

- ↑ Joe Morella, Edward Z. Epstein: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Delacorte Press, New York 1983, pp. 211-215.

- ↑ a b c Joe Morella, Edward Z. Epstein: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Delacorte Press, New York 1983, pp. 220-225.

- ↑ Joe Morella, Edward Z. Epstein: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Delacorte Press, New York 1983, pp. 227-228.

- ↑ "Rita at forty-seven has never looked less like a beauty, or more like an actress." Time quote after Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, p. 234.

- ^ A b Joe Morella, Edward Z. Epstein: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Delacorte Press, New York 1983, pp. 231-233.

- ↑ “The irony of Rita Hayworth's career is that she is making fewer (and increasingly obscure) pictures but is giving better and better performances." Kevin Thomas quoted in Los Angeles Times . after Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, p. 244.

- ^ Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, p. 245.

- ↑ Marli Feldvoß: Speaking of Rita Hayworth . New Critique Publishing House, Frankfurt am Main 1996, p. 39.

- ↑ Joe Morella, Edward Z. Epstein: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Delacorte Press, New York 1983, p. 249.

- ↑ Manuel Puig: La traición de Rita Hayworth. Jorge Álvarez, Buenos Aires 1968 (Colección narradores argentinos). English: Betrayed by Rita Hayworth. Novel. Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch, 344, 1st edition, Frankfurt / M. 1976, ISBN 3-518-06844-X .

- ↑ Diana Garcia Simon: The first novel - La traición de Rita Hayworth ( Memento from October 26, 2017 in the Internet Archive ) on lyrikwelt.de

- ^ Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, pp. 200/256.

- ↑ Bernard Weinraub: An Animator Breaks Old Rules And New Ground in 'Roger Rabbit' . In: The New York Times , August 1, 1988.

- ^ Tony Magistrale: The Films of Stephen King. From Carrie to Secret Window . Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Roger Ebert : Mulholland Drive . In: Chicago Sun-Times , October 12, 2001.

- ↑ Ed Kellerher: Notting Hill . In: Filmjournal International , November 2, 2004.

- ^ Katja Schumann: Film genres: crime film . Reclam, 2005, p. 355.

- ↑ Manohla Dargis : The Pop Spectacular That Almost Was . In: The New York Times , October 29, 2009.

- ↑ Shari Benstock (ed.), Suzanne Ferriss (ed.): On Fashion . Rutgers University Press, 1994, p. 174.

- ↑ Nick Hasted: Jack White. How He Built an Empire From the Blues . Enhanced Edition. Omnibus Press, 2016.

- ^ David Fricke: The Mysterious Case of the White Stripes . In: Rolling Stone , September 8, 2005.

- ↑ Mike Robinson: A Brief History of Jack White's Guitar Collection on myrareguitars.com, April 14, 2014.

- ↑ cf. synchrondatenbank.de ( Memento from April 6, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Rita Hayworth. In: synchronkartei.de. German synchronous index , accessed on October 1, 2018 .

- ↑ cf. otrsite.com

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hayworth, Rita |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cansino, Margarita Carmen (real name); Cansino, Rita |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | US-american actress |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 17, 1918 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | New York City , New York , United States |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 14, 1987 |

| Place of death | New York City , New York , United States |