Gilda (film)

| Movie | |

|---|---|

| German title | Gilda |

| Original title | Gilda |

| Country of production | United States |

| original language | English |

| Publishing year | 1946 |

| length | 110 minutes |

| Age rating | FSK 12 (previously 16) |

| Rod | |

| Director | Charles Vidor |

| script |

Marion Parsonnet , Jo Eisinger , Ben Hecht , Virginia Van Upp |

| production | Virginia Van Upp |

| music | Hugo Friedhofer |

| camera | Rudolph Maté |

| cut | Charles Nelson |

| occupation | |

| |

Gilda is an American fiction film in the style of film noir from 1946. It is a mixture of crime film and melodrama in which love-hate relationship is the central theme. Directed by Charles Vidor , Rita Hayworth stars in the title role. As the erotic classic of the “ Black Series ”, Gilda is particularly famous for Hayworth's legendary glove striptease to Put the Blame on Mame , which shaped her image as the goddess of love in the 1940s.

action

The young American Johnny Farrell wins a large sum of money by cheating at a game of dice in the port of Buenos Aires . When a thief then attacks him, a mysterious wealthy man shows up with a knife that pops out of his walking stick and saves Johnny's life. The stranger introduces himself as Ballin Mundson and advises him not to continue his cheating in a certain casino . Johnny ignores his advice and shows up at the casino. When he is convicted of cheating while playing Black Jack , he is brought to the owner of the casino, who turns out to be Ballin Mundson. Johnny persuades Ballin to hire him and quickly proves to be the trustworthy man of his new boss. Both have similarly pessimistic worldviews, especially when it comes to women, which is why a male friendship develops between them.

When Ballin unexpectedly returns as a new husband from a business trip, Johnny is amazed to see the attractive Gilda, whom Ballin introduces as his wife. It is the same woman with whom Johnny once had a passionate love affair, the failure of which led him to go to South America . Both he and Gilda try to keep up appearances from Ballin that they don't know each other. Behind the mock indifference for each other, however, the feelings of the two quickly boil up again, especially when Ballin assigns Johnny to take care of Gilda. Out of old resentment, but also out of loyalty to Ballin, Johnny subsequently avoids any intimacy with Gilda. Offended by his rejection, Gilda enjoys making him jealous of other men. Since Johnny is convinced of Gilda's alleged disloyalty to Ballin, his already ambiguous feelings for her increasingly turn into hatred. Only the casino employee Uncle Pio knows how to see through the emotionally charged situation and to interpret it correctly as an outsider.

Ballin, who is secretly involved in an international cartel for tungsten smuggling with a seedy German organization , is under pressure. The government official, Detective Maurice Obregon, is already on the trail of him and two German businessmen, and for this purpose spends a lot of time at the gaming tables. When the two Germans see themselves cheated out of the cartel by Ballin, Ballin kills one of them and is forced to flee. He returns home to find Johnny and Gilda in the bedroom, kissing in each other's arms after another feud. Ballin immediately leaves the house and fakes his suicide with a plane crash. Since he has stipulated in his will that Gilda should inherit his fortune and several tungsten patents, Johnny decides to take Gilda as his wife. Now that she is going to marry the man she really loves, Gilda looks hopefully into the future together. However, Johnny cannot forgive her for her apparent infidelity and wants to punish her by keeping her imprisoned in a cage and neither visiting nor letting her go out.

When Gilda cannot find any other way out of her oppressive situation, she flees to Montevideo . There she appears as a celebrated dancer and meets the lawyer Thomas Langford, who wants to help her divorce Johnny. However, the lawyer is a straw man for her husband who brings her back to him directly. Gilda furiously beats Johnny, only to beg for her divorce at his feet shortly afterwards. Since Johnny still does not allow himself to be softened, Gilda tries to take revenge on him in her own way: She does a provocative striptease in the casino so that everyone can see what kind of shameless woman Johnny seems to have married. Johnny indignantly pulls her off the stage and slaps her across the face. Troubled by his guilty conscience, Johnny is found by Detective Obregon, who finally convinces him that Gilda has always been loyal and has only acted for him.

Johnny humbly returns to Gilda and asks her to forgive him. Both see how mean they were to each other, but that they still belong together. At that moment Ballin, believed dead, appears and demands his wife back. He approaches her with a loaded pistol and threatens to kill Gilda too. However, Uncle Pio manages to stab Ballin at the last moment. Obregon, who is still at the casino due to the ongoing cartel investigation, joins them shortly thereafter. Despite Johnny's knightly endeavors to take the sole blame for Ballin's death on himself, Obregon releases him from the situation, since Ballin had already committed suicide three months earlier and it was also uncle Pio's self-defense. Relieved and happy Gilda asks Johnny to leave with the words "Let's go home".

background

script

The plot is based on a story by the author E. A. Ellington, which was first adapted for the screen by Jo Eisinger on behalf of Columbia Pictures and then worked out by the screenwriter Marion Parsonnet . Since there was no complete script at the start of shooting, Ben Hecht was also used as the author, but without being mentioned later in the credits. But above all Virginia Van Upp , who acted as the producer of the film and had already successfully produced a Hayworth film with Es tanzt die Göttin (1944), added crucial dialogues and character drawings to the script. Knowing Rita Hayworth well, Van Upp was able to tailor the role of the seductive Gilda to the actress and adapt the dialogue for her accordingly.

Due to the censorship in Hollywood, however, the erotic elements of the plot, including possible homosexual tensions between Johnny and Ballin or Gilda's sexual needs, were only allowed to be hinted at, which is why the film developed its own subtext, which both the Production Code and many US-American ones Time passed by critics. Legendary lines like “If I were a ranch, I would be called unlimited freedom.” (“ If I'd been a ranch, they would have named me 'The Bar Nothing'. ”) Nevertheless made it into the script.

occupation

Since the film was anticipated as the vehicle for Rita Hayworth, Columbia's greatest star, her cast as the title hero was out of the question. Humphrey Bogart was initially discussed for the male lead . However, this refused Columbia's offer on the grounds that with a woman as beautiful as Hayworth no viewer would notice him on screen and that, in his opinion, it was a women's film. The role of Johnny Farrell was finally given to Glenn Ford , who was also under contract with Columbia and had only shot a new film, The Big Lie (1946) with Bette Davis , after his three-year navy service in World War II . He and Hayworth already knew each other from filming The Lady in Question (1940), which Charles Vidor had also directed.

George Macready , whose face adorned a striking scar, was cast as the villain Ballin Mundson. The short-grown Hungarian Steven Geray , on the other hand, seemed to the producers to be perfect for the role of Uncle Pio, while the Maltese actor Joseph Calleia, with his Mediterranean appearance, played one of his most famous roles as the Argentine law enforcement officer Detective Obregon.

Filming

Filming began on September 7, 1945. Despite the exotic locations, all but the beach scene in which Mundson staged his suicide took place entirely in the Columbia studios. Since the script was not yet finished at this point in time and therefore could not be fully approved by the production code, those involved sometimes did not know how the plot would go and the film should end. Similar to the shooting of Michael Curtiz ' Casablanca (1942), the actors mostly only received their dialogues on the morning of the day of shooting, which made the production by director Charles Vidor anything but easy. It wasn't an easy shoot for Rita Hayworth anyway, as her marriage to director Orson Welles fell apart during this time and they both announced their separation. In addition, she was troubled by the control addiction of studio boss Harry Cohn , who had an employee monitor her and equip the studio and all cloakrooms with bugs so that he could find out everything that was going on in his studio.

Hayworth and her co-star Glenn Ford hit it off perfectly. Due to their extremely strong chemistry in front of the camera, journalists speculated about a possible romance between the two actors while filming. Ford later said: "Rita and I liked each other very much, we became very close friends, which I think was also shown on the screen." According to him, Charles Vidor was very strict and demanding as a director and had his when shooting Given very unusual instructions to performers to get the effect they wanted. In the knowledge that they were working together on a special film, according to Ford, there was a certain excitement among everyone involved on the set until the end of the shooting on December 10, 1945.

Since Vidor had previously worked with Hayworth twice, whom he also referred to as his favorite actress, he was already familiar with her acting skills. According to him, his leading actress only needed two takes for her appearance on Put the Blame on Mame . In general, Hayworth was able to call up her best performance mostly on the second, sometimes on the third take. If the recording of a scene had to be repeated more than once, it became difficult for Vidor because Hayworth was not a methodical, but an emotional actress who was emotionally exhausted after more than three takes. Especially in the scene when Hayworth was about to hit Glenn Ford wildly, it was difficult for her to overcome herself because it completely contradicted her own being.

Music and dance numbers

In the crime films of the studio era , singing interludes were sometimes performed, for example by Lauren Bacall in Dead Sleep Firm (1946) or by Ava Gardner in Avengers of the Underworld (1946). Dance interludes such as in film musicals , on the other hand, are extremely rare in film noirs , in which the female protagonists in particular are mostly portrayed passively and statically. In addition to her beauty, Rita Hayworth was best known for her dancing talent, which she had already demonstrated in films with Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly . Therefore, she was granted two dance interludes to the songs Amado Mio and Put the Blame on Mame in Gilda , which should also underline the seductive power of her role. Hayworth sang, as in all of her films, but not herself and was dubbed in this case by the singer Anita Ellis . Allegedly, Hayworth is said to have sung the simple guitar version of Put the Blame on Mame in the film, but Anita Ellis gave her the voice at this point as well. The two songs were written by Doris Fisher and Allan Roberts , while the choreographer Jack Cole was responsible for the dances :

- Amado Mio : After Gilda married Johnny, who wants to punish her for her alleged sins out of loyalty to Ballin and therefore isolates her from the outside world, she flees to Montevideo . In order to earn a living, Gilda appears in a local nightclub, where she performs the song Amado Mio (English: "My darling") to rumbar rhythms. Hayworth is dressed in a two-piece white outfit with golden ornaments and moves with mostly spread arms and slowly circling hip movements, which alternate briefly with quick turns and jumps. The title of the song is Spanish according to the Latin American setting, but the remaining lines of the song are in English and describe Gilda's longing for fulfilled love.

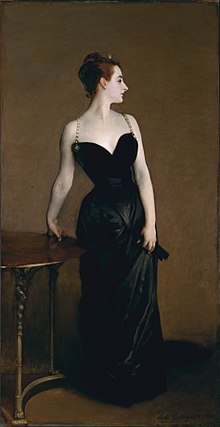

- Put the Blame on Mame : When Gilda is brought back from Langford to Johnny inBuenos Aires, but he still does not want to consent to a divorce, Gilda performs astripteasein front of an enthusiastic audience in the casinoto the songPut the Blame on Mame(Eng .: "Blame Mame"), which she sang to Uncle Pio in a previous scene and accompanied herself on the guitar. While Gilda recited the song calmly and melancholy in that scene, she appears self-confident and provocative in the casino. Her performance is supposed to humiliate Johnny, but it also has serious undertones and thus becomes a kind of soul striptease. With the lyrics Gilda describes in an ironic accusatory way how men always blame women and female power ("Mame") unjustifiably for all catastrophes, such as theGreat Fire of Chicagoor theSan Francisco earthquake of 1906. Hayworth wears a black strapless satin dress with matchingevening gloves, one of which shestrips offwith deliberately ambiguous erotic gestures in the style ofburlesquedance. Her lush mane of hair is also prominently used. Years later, choreographer Jack Cole was still very proud of this scene: “I have to say, of everything I've done in film, it's one of the few scenes that I can still see on screen and that I would say about : If you want to see a beautiful, erotic woman, this is just the thing. It's still top notch. "

Costumes

For the costumes of the film, Columbia's studio designer Jean Louis was hired, who had already designed the clothes for Rita Hayworth in the film musical Tonight and Every Night (1945). Both worked together many more times later. Jean Louis attested Hayworth a good figure with slender legs, long arms and beautiful hands, so that it was not difficult for him to dress her. However, since Hayworth had become a mother at the end of 1944, Jean Louis was now primarily responsible for hiding her belly that was still there.

His extravagant robes worth 60,000 dollars played a major role in portraying the title character and at the same time had a lasting impact on Hayworth's image. Jean Louis emphasized Hayworth's shoulders and arms in his work and relied on very tight-fitting fabrics that should give the actress a narrower waist. With sequins , gold lamé , fur , velvet , satin and black nylon stockings , the designer identified Gilda and Hayworth as a glamorous icon, in which very feminine dresses alternate with broad-shouldered and therefore more masculine-looking costumes.

In her first scene, when she lasciviously tosses her hair back, Hayworth only wears a strapless negligee that suggests a certain nudity to the viewer and thus immediately reveals the seductive power of her role. Amazingly, the Production Code did not complain about this get-up or the one in the scene when Gilda is talking to her maid wearing a white negligee that covers her shoulders, but through which you can see her bare bosom. In other scenes, Hayworth can also be seen in white costumes, some of which were embroidered with glittering and gold ornaments, such as her two-piece Amado Mio outfit, which also covers her shoulders but reveals her waist.

Jean Louis was inspired by John Singer Sargent's painting Madame X for the famous black satin dress that Hayworth wears during her appearance on Put the Blame on Mame . In order to prevent the strapless dress from slipping and unintentionally exposing Hayworth with her sweeping strip insert, Jean Louis reinforced the upper part of the robe with a plastic frame that held Hayworth's bosom like a corset , while a large black bow was intended to divert attention from her stomach.

In 1953, William Travilla , designer at 20th Century Fox , copied this dress for Marilyn Monroe , who preferred it to show off her famous show for Diamonds Are a Girl's Best Friend in blondes . Travilla only changed the color from black, which is typical for film noir, to bright pink.

Film analysis

Themes and motifs

Location and contemporary history

The film was originally set to take place in the United States. But as with Alfred Hitchcock's Notorious (1946), South America was ultimately chosen as the setting for Gilda , which gave the script more freedom in terms of the criminal plot and the erotic aspects. While Infamous is set in Rio de Janeiro , two Latin American metropolises serve as exotic backdrops in Gilda , where, from the North American point of view, in their “decadence, the usual moral concepts do not apply”. While the main part of the action takes place in Buenos Aires , the scene changes for a few minutes to Montevideo , where Gilda appears as a singer and dancer in a nightclub. As in Casablanca (1942), most of Gilda's scenes take place in an illegal casino, which, as a traditional location for criminal machinations, represents a depraved form of capitalism and which, in addition to the carnival taking place, despite the censorship, once again offers the viewer immoral excesses showcase.

Even the period of the plot with its confused circumstances - the Second World War has just ended and soldiers stationed around the world are returning home - allows the actors a brief blossoming of previously suppressed desires and vicious longings.

Role models

The supposed noir hero

Johnny Farrell is introduced as the protagonist and narrator of the film in the opening scene. With Ballin Mundson, through whom he rises from poor dice player to manager of the casino and whom he increasingly tries to imitate, he shares the view that gambling and women do not belong together. For him, the cynic and pessimist, attractive women like Gilda are lying, greedy and unfaithful. His obvious misogyny is expressed, among other things, with sentences such as “According to statistics there are more women in the world than anything else - except insects .” (“ Statistics show that there are more women in the world than anything else - except insects! ”)

But although the film is told by him and he initially advanced to a noir hero through his youthful energy, he ultimately turns out to be a misguided and jealous sadist who is belied by the scenes of a vulnerable Gilda. Because he misinterprets Gilda's behavior out of his sexual frustration, he loses all authority as a narrator.

The alleged femme fatale

With her loose hair, bare shoulders, sensually made-up lips, long eyelashes and the obligatory cigarette between her painted fingernails, Gilda is externally identified as a seductive woman in her first scene. Shoes with platform soles and ankle straps also illustrate her passive masochistic manner elsewhere. But although Gilda is mostly described as an iconic femme fatale , she is more like a "bad good girl" who initially appears as a dangerous vamp, but ultimately turns out to be good and good shows honestly.

Gilda, who reacts to Johnny's cynicism with raised eyebrows in derision, is a sexually emancipated woman who, through Johnny's mortification and sexual frustration, merely pretends to be an unfaithful, male-murdering femme fatale. Her “power that reveals itself with the independent development of female sexuality” is branded as “destructive and destructive”. But “dancers are generally not really bad girls”, which “already physically contradicts the static, passive style of film noir”. Gilda's striptease to Put the Blame on Mame initially represents the "ultimate, visual incarnation of the seductive, sexually available bad girl", but reveals itself as an ironic lament with which she reveals herself as the misunderstood and real heroine of the film.

The ultimate villain

Ballin Mundson appears as a wealthy, always elegantly dressed businessman in the style of a dandy . He runs an illegal casino and is at the head of a tungsten cartel with which he wants to control the world, just as he can watch his casino from his office through blinds and control it via switching devices. He appears humorless, dictatorial and cold-hearted. For Johnny, but also for Gilda, he represents an authoritarian father figure who is to be liked and whose anger is to be feared if disobedient. For him, Gilda is a trophy which, in addition to his global aspirations and his "little friend", the walking stick with a protruding knife blade, serves as a compensation for his implied impotence . In order to maintain power, he does not shy away from murder or from his own staged suicide.

The philosopher and the lawman

Opposite the three main actors are two secondary characters who, especially in contrast to Johnny, have a better overview of the situation or Gilda can correctly assess and thus take over the viewer's perspective. The stunted Uncle Pio, who as an employee in the washroom has the lowest rank in the film, is always superior to the other characters and one step ahead due to his proximity to the rumor mill. With the words " The worm's eye view is so often the true one. ", He gets to the point. In addition, as the voice of the people, in view of the melodramatic plot with his philosophical and mocking comments, he ensures comedic balance. He even prevents a tragedy by stabbing Ballin with his walking stick before he can kill Gilda and Johnny.

In contrast, the tall Detective Obregon takes on the role of the serious and equally astute law enforcement officer who restores law and order with his investigations into the cartel and the closure of the casino. It is also he who, with his authority, is the only one who succeeds in convincing Johnny that Gilda was only playing the femme fatale. He proves to be an exemplary and true father figure for Johnny compared to Ballin.

Eroticism and Freudian symbolism

In order to smuggle the film past the prudish and strict guidelines of the Production Code , any erotic topic such as sexual desire, homosexuality , voyeurism and sadomasochism had to be disguised with ambiguous dialogues and encrypted symbols. By the time the film was made, Hollywood had already developed a system of codes to circumvent censorship. Gilda took up “this with a wink” and proved “to be an ironic commentary on the grotesque self-censorship of the film industry”. This is expressed "in Gilda's dance as clearly as in the filmmakers' apparent pleasure in trivializing Freudian symbolism".

Due to the absence of women, intense glances and mutual cigarette lighting at the beginning of the film indicate homoerotic tension between Johnny Farrell and Ballin Mundson, reflecting the situation of soldiers during World War II, when sexual contact with women was rare. But any confusion about the two men's own sexuality evaporates when a decidedly feminine and seductive woman in the form of Gilda presses between them. A ménage à trois develops that refers to Ernst Lubitsch's film comedy Serenade zu threitt (1933), in which the main female character was characteristically Gilda Farrell.

In this love triangle, Johnny embodies the young and strong man who has to decide in a scene whether he wants to give in to his desire for Gilda and appear as a potent bull at the carnival or - out of loyalty to his employer and friend - end up as a fool. He is contrasted with the older and impotent Ballin, who tries to compensate for his lack of masculinity and asexuality with his walking stick including a protruding knife tip as a phallic symbol. Gilda, who is a trophy for Ballin, symbolizes beauty, love and eroticism as a modern version of Aphrodite . In front of Ballin's office in the casino there is a black statue of the goddess of love based on the Greek model, which is shown passively without arms. In her dance performance for Put the Blame on Mame , in which Gilda wears long black gloves that make her appear like an armless torso against the black background, Gilda changes from a passive object of desire into an active subject and “optically conquers her physical one Back to integrity ”by“ taking off her gloves and gradually baring her arms while dancing ”. Gilda's idea therefore “not only uses male voyeurism”, which manifests itself primarily in the view through the steel blinds in the casino, “but also shows her as a woman who cannot be reduced to an object”.

The dance serves as a traditional allegory for the sexual act. In the carnival scene, when Gilda and Johnny move arm in arm to the beat of the music, Gilda is talking about dancing. However, she actually alludes to her previous nights of love with Johnny, admitting that no one can "dance" like him and that she wants to help him get back into practice or become sexually active again. Because Gilda confidently flaunts her sexuality and reveals her intimate longings with her supposed promiscuity , "she becomes a problem for men", especially for Johnny, "whose [own] frustrations stand out clearly in his harshness". His resulting sadistic behavior manifests itself both physically in the form of slaps in the face and psychologically when he denies Gilda the wedding night and isolates her from the outside world. Johnny's discontent and jealousy are not only influenced by his rivalry, but also by his friendship with Ballin. In his appearance as a father figure, the latter also turns the triangular relationship into a variation of the Oedipus conflict in the sense of psychoanalysis .

Gilda in particular often draws attention to the teachings of Sigmund Freud with her lines of dialogue when she says sentences like: “Any psychiatrist would tell you that your thought associations are very revealing. Any psychiatrist would tell you that means something. ” (“ Any psychiatrist would tell you that your thought associations are very revealing. Any psychiatrist would tell you that means something. ”) Or“ I never get a zipper. That might mean something. Don't you think so too? ”(“ I can never get a zipper to close. Maybe that stands for something. What do you think? ”) Just like the zipper, the window in Gilda's bedroom also illustrates the access to the female lap. When Carnival is celebrated in the streets of Buenos Aires, Ballin tells Gilda to close it: “Do you see how quiet it is now? It's so easy to shut out the excitement just by closing a window. ” (“ See how quiet it is now? See how easy one can shut away excitement, just by closing a window. ”) The whip that Gilda then to hers Wearing a costume, together with her eye mask alludes once more to her sadomasochistic relationship with Johnny. In addition to Ballin's walking stick, the cigarette also serves as a phallic symbol, especially in a scene when Gilda wants Johnny to light a cigarette and is forced by him to bend down by holding the lighter at his waist. The frequent smoking of the two also illustrates their respective sexual frustrations.

Love-hate relationship

The moment Johnny and Gilda first meet in the film, their surprised faces reveal that they already know each other. Their subsequent dialogues immediately reveal their mutual dislike for one another. Shortly afterwards it turns out that both once had a love affair, but this ended in a breakup, since Johnny apparently had doubted Gilda's loyalty in the past and therefore left her. While Johnny continues to regard Gilda as a faithless woman and despises her for it, Gilda is deeply offended by his renewed rejection. Nevertheless, they continue to feel drawn to each other, with the result that Johnny feels increasingly hostile towards Gilda as his friend's wife and thus as a forbidden object of desire: "I hated her so much that I never got it out of my head." I hated her so, I couldn't get her out of my mind for a minute. ")

Gilda, in turn, would like to take revenge on him, even if it should harm her: " I hate you so much that I would even destroy myself to destroy you." (" I hate you so much that I would destroy myself." to take you down with me. ”) Gilda doesn't turn her hatred into murder. Instead, she lives out her hurt feelings of love and enjoys making Johnny jealous and tormenting him with her sexual unavailability. Later it is Johnny who makes himself sexually unreachable. This corresponds to a “game of submission and dominance” in which “female sexuality and male desire collide” and are also reflected in sadomasochistic acts such as mutual humiliation and slaps in the face.

Ballin also notices the tension between his deputy and his wife, which leads him to confess to Gilda: “Hate can be a very exciting feeling. There's a passion in it that you can feel. Hate is the only thing that has ever warmed me. ” (“ Hate can be a very exciting emotion. There is a heat in it that one can feel. Hate is the only thing that has ever warmed me. ”). Hate and love or sexual attraction are therefore on the same level and develop in their opposition to one and the same passion that stimulates Johnny and Gilda all the more until Gilda can no longer bear it and Johnny takes up Ballin's words: “Hate is really an exciting feeling. Haven't you noticed yet? Very exciting. I hate you too, johnny. So indescribable. I think I'll have to die from it. "(" Hate is a very exciting emotion. Haven't you noticed? Very exciting. I hate you, too, Johnny. I hate you so much that I think I'm going to die from it. ”) This is followed by a passionate kiss, with which both their pent-up desire and their hatred for one another are briefly discharged.

Ballin's alleged suicide, for which Johnny then blames Gilda, rekindles their mutual aversion. Shortly before the end, Detective Obregon brings this issue up again openly when he says to Johnny: "It's the strangest love-hate pattern I've ever had the privilege to watch." (" It's the most curious love-hate pattern I've." ever had the priviledge of witnessing. ")

happy end

The final scene, in which Gilda and Johnny are reconciled and want to return to the United States together, corresponds to a “reversal of the usual noir ending”. While the male and female protagonists in film noirs like Woman Without a Conscience (1944) and In the Net of Passions (1946) are punished with death for their sexual desires and sins, Johnny and Gilda save themselves as immature children in a happy ending . Marriage and the United States represent the safe haven. But only Ballin's sudden return, his now also for Johnny evidently wickedness and his subsequent death at his own weapon make a happy ending for the two lovers possible.

The fact that Johnny Gilda humbly and ruefully asks forgiveness for his mistrust and dismissive behavior and that she wants to be content with a married life as a tamed woman was often perceived by critics as implausible and artificial in the sense of a concession to the censorship. In the context of the time, however, the happy ending after the war-related alienation of the sexes should rather be seen as a positive signal to American GIs who returned to their wives after the Second World War and, like Johnny, doubted the loyalty of women.

Staging

dramaturgy

Most of the plot is told by Johnny Farrell in the voice-over typical of the film noir as a flashback and therefore from his perspective. However, since he is not present in every scene, his view of things turns out to be limited or subjective and therefore unreliable. Scenes in which Ballin's unscrupulousness and true intentions are revealed to the viewer, or moments in which it becomes clear that Gilda is merely playing the promiscuous woman, escape Johnny's attention. However, they influence the viewer as the plot progresses more than Johnny's off- screen words , with which he mostly expresses his loyalty to Ballin and his hatred of Gilda. This creates tension for the viewer, who has to decide whether to believe Johnny's remarks or the images shown. This decision is made easier for the viewer by the conventions of film language, according to which words can be wrong, but pictures do not lie. The recordings, which contradict Johnny's statements, are also confirmed and thus legitimized by two outside figures - Uncle Pio and Detective Obregon - with their respective comments.

Johnny's flashback ends prematurely when Gilda is brought back to him in Buenos Aires by Thomas Langford. This is followed by the climax of the film with Gilda's appearance on Put the Blame on Mame . The striptease, in which Gilda only takes off her arm-length gloves and her diamond necklace, symbolizes the narrative structure of the film, in that layer by layer Gilda's true kind-hearted nature is revealed under the costume of the femme fatale.

Visual style

According to Gerald Peary, director Charles Vidor succeeded in Gilda in combining “the smoke-covered, veiled scenes” of Josef von Sternberg's Der Teufel ist ein Frau (1935) “with the brilliantly moving camera and the photographic angles” of Michael Curtiz 's Casablanca . François Truffaut , on the other hand, said that the visual quality of the film was not due to Vidor's direction, but rather to Rudolph Maté's work as a cameraman.

In the style of film noir, Gilda is optically shaped above all by the play of light and shadow. The scenes in the casino are mostly dominated by strong high-key lighting , while the low-key lighting gives the harbor or Gilda's bedroom a dodgy or mysterious atmosphere. In Ballin Mundson's portrayal, the lighting varies greatly from time to time. It is often particularly brightly lit so that it looks very pale and icy. Elsewhere it is again wrapped in dark shadows or only shown its black, mysterious silhouette. In Gilda's dance interludes to Amado Mio and Put the Blame on Mame , her surroundings, bathed in darkness, in the nightclub or casino, including the orchestra and audience, are barely recognizable, while Gilda herself is brightly lit and her movements are followed according to the male gaze by the headlights . Because she is also illuminated from behind, a ring of light is created around her hair, which additionally emphasizes her goddess-like aura. In addition, the editing, the camera work and the mise-en-scène mark Gilda as a clear object of desire for both the male protagonists and the male audience.

Usually, key actors in a film are staged in their first close-up motionless. But through movement, the youthfulness and vitality of Johnny and Gilda are already illustrated in their first scenes. Johnny Farrell is shown at the beginning of the film throwing two dice in the direction of the camera, which moves up from a frog's perspective . Gilda's first appearance, which only takes place after 17 minutes and is announced by her hum to the melody of Put the Blame on Mame , is even more marked by movement, although in this case the camera stands still. When Ballin asks: “Gilda, are you dressed?” (“ Gilda, are you decent? ”), There is a cut into the empty space, whereupon Gilda, in a close shot and in half profile, sweeping her lush hair from bottom to top throws in the neck and replies: “Me? Of course I'm dressed. "(" Me? Sure, I'm decent. ")

It is also noticeable that all male actors are shown in their close-ups in sharp image quality, so that their scars and other external deficits stand out clearly, while Hayworth is always presented with a soft focus as a flawless beauty.

reception

Publication and aftermath

United States

The world premiere of Gilda took place on March 14, 1946 at New York's renowned Radio City Music Hall , where the film was shown for three weeks. On April 25 of the same year, it came into general distribution in the United States. The contemporary reviews were partly devastating or at least mixed. The box office totaled a whopping 3.8 million dollars, making the film one of the 20 most successful films of the year in the USA and the second biggest hit of 1946 for Columbia Pictures . The film, which was equally popular with men and women, cemented Rita Hayworth's reputation as the screen goddess of the 1940s while also making Glenn Ford a star. The dreaded critic of the New York Times , Bosley Crowther , who otherwise couldn't get anything from the film and the acting qualities of the leading actress, even attested Hayworth the title “Superstar” after seeing her as Gilda.

Since Hayworth was particularly popular as a pin-up girl with the returning GIs and Columbia also made the film alluding to her status as a “sex bomb” with slogans such as “Beautiful, Deadly… Using all a woman's weapons…” , fatal ... With all a woman's weapons ... ”) in the cinema trailer, the first atomic bomb that was detonated on June 30, 1946 as part of“ Operation Crossroads ”for test purposes on the Bikini Atoll , was christened“ Gilda ” and decorated with a photo of Hayworth, to which the actress responded with dismay.

Hayworth later complained that the role of Gilda had had an irrevocable effect on her personal life. She is said to have uttered the famous words to Virginia Van Upp: “Every man I've known has fallen in love with Gilda and wakened with me.” (Eng: “Every man I knew fell in love with Gilda, but woke up up with me. ”) From then on, committed to the type of the sensual goddess, Hayworth found it difficult to prove herself as a character actress with increasing age. Above all, Columbia's boss Harry Cohn always wanted to stick to her Gilda image in order to achieve the greatest possible profit at the box office. When Hayworth returned to Hollywood in 1951 after a film break of several years through her marriage to Prince Aly Khan and was aiming for a comeback, Cohn relied again on Gilda's successful concept . For the resulting film Affair in Trinidad (1952) Van Upp was hired again as a producer, Glenn Ford was used as Hayworth's co-star and Uncle Pio and Steven Geray were again seen in a supporting role. Above all, the crime story and Hayworth's dance interludes, but also the exotic setting borrowed heavily from Gilda , which neither the critics nor the audience missed. In 1957, Hayworth finally got the chance to parody her Gilda image when she ironically performed a glove striptease as a rich widow with a past in the Broadway film adaptation of Pal Joey .

Europe

In Europe , the film was first shown in September 1946 at the Cannes International Film Festival , where the film took part in the competition for the Grand Prix des Festival. For Europeans, Gilda embodied as a film and as a role unreal Hollywood glamor, which was able to distract from the sober post-war everyday life. In Italy , the role of the erotic but innocent Gilda established an enormous star cult around Hayworth. In the heart of Rome there was a classy disco called "Gilda", which is still very popular today.

In Spain , however, the film sparked a scandal in 1947 when Falangists from the Franco regime in Madrid smeared Gilda film posters with paint and churchmen threatened every viewer with condemnation for what they saw as the immoral portrayals of the film. This scandal made the film title on the Iberian Peninsula a synonym for the repression that the Spanish population suffered under the dictatorship, especially during the 1940s. Above all, the protest of the Catholic Church gave Gilda such an erotic aura for the Spaniards that they were convinced that Hayworth undressed completely after Put the Blame on Mame , but this scene was cut out. As a result, photomontages were circulating in Spain that showed Hayworth's face on a naked woman's body.

In Germany , Gilda first came to cinemas on December 29, 1949. On July 21, 1988, the film drama was shown again in a second, more faithful dubbing version in German cinemas. In 1999 the film was released on DVD. A release on Blu-ray followed in 2014 .

Reviews

The judgment of Bosley Crowther , the critic of the New York Times , was devastating at the time. In her first really dramatic role, Rita Hayworth shows "little talent that should be praised or promoted". Despite a multitude of glittering gowns and the glamorous way in which she throws her hair back, "her way of playing a lady of the world is clearly on the level of a dime novel". Her screen partner Glenn Ford proved "at least a certain stamina". The director Charles Vidor, Columbia's producer Virginia Van Upp and the writers deserved no mention, according to Crowther. Together they would have made Gilda “a slow, operatic and not very captivating film”. Also Time was not convinced of the spectacle lead performance. The film is "the result of the heavenly Rita Hayworth's longing to prove that she can act". However, she has proven “that she is such an eye-catcher that everything else hardly counts”.

The industry journal Variety was more conciliatory . Hayworth is "wonderfully staged". The makers of the film were "anything but subtle in the projection of their sex appeal". The direction is "static", but that is more due to the script. Kate Cameron of the New York Daily News was also more benevolent of the film. The characters are "interesting and played well enough". Although the plot has "all elements of high-class kitsch", the director and his experienced cast have given it "a considerable, magnetic force" by keeping the audience in suspense "from one dramatic turn to another".

In retrospect, Kim Newman stated that Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford were “limited but attractive and photogenic actors” who had “absolutely convincing performances” in Gilda , while Macready also shone “as the complex villain”. Leonard Maltin gave the film three out of four stars and called it a “highly charged story of a love triangle” that ultimately backs down “with a silly resolution”. However, Hayworth was "never sexier". Lucia Bozzola from the All Movie Guide found that Hayworth's striptease made the film “a remarkable example of the erotically charged film noirs” - “despite the censorship-friendly good-girl ending”.

The British film critic Philip French praised Rudolph Maté's camera work in the Observer and described the film as a “wonderfully perverted noir classic that is a mixture of Casablanca […] and Hitchcock's notorious ”. The Guardian gave the film four out of five stars and called it a "classic melo noir" that looked like the "crazy, evil twin of Michael Curtiz ' Casablanca ". It is "a real treat from Hollywood of the 1940s".

On the occasion of a re-release of the film in German cinemas, Andreas Kilb wrote for Die Zeit in 1988 that Gilda was “not a film to taste and reason”, “but one to hate and love, to cry and chatter teeth”. The viewer is offered “emotional cinema in superlatives”. The plot is "absurd", but also "as moving as the greatest tragedies in cinema". Kilb concluded: “Charles Vidor has never made a better film than this bad one. And Rita Hayworth was never more beautiful than in Gilda . ” That same year, Der Spiegel described the Columbia production as“ a film of so perverted innocence ”that Hayworth's mere removal of arm-length gloves“ becomes an obscene striptease ”.

For the lexicon of international film , Gilda was “[e] in an excellently played and staged classic” from film noir, “which, beyond the stereotypical crime story, deals with the feelings between man and woman and the genre elements into an almost philosophical essay about love and the utopia of life embodied therein connects ". Prisma called Hayworth's striptease for Put the Blame on Mame a "legendary scene" and saw it as the undisputed climax of the film. The result was "effective entertainment", which had increased Hayworth's popularity as a seductive film star. Cinema summed up the film with the conclusion “[s] pannend, sexy and wicked” .

Awards

At the first Cannes International Film Festival in 1946 , Gilda took part in films such as Alfred Hitchcock's Notorious and Billy Wilder's The Lost Weekend in the competition for the Grand Prix, which was awarded by the Festival's jury for outstanding films, before the Palme d'Or in 1955 as the most important Award replaced. However, Gilda could not prevail against the mainly European competition. The American Film Institute chose in 2003 the US movie poster premiere of the Gilda No. 1 on the best classic movie posters. It shows Rita Hayworth in a light blue silk evening dress with a cigarette in one hand and a mink stole in the other in front of a black background on which the slogan “There NEVER was a woman like Gilda!” (German: “NEVER was one Woman like Gilda! ”) Can be read. A year later, Put the Blame on Mame was voted number 84 on the AFI list of the best American film songs. In 2013 it was accepted into the National Film Registry .

Classification and evaluation

In one of the first essays on film noir , the two Frenchmen Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumeton wrote as early as 1955 that Gilda, as “an almost indefinable film in which eroticism triumphs over violence and strangeness”, is sleeping alongside the dead within the “Black Series” (1946) and The Lady of Shanghai (1947) are among the "outstanding films in cinema history". A year later, the French film critic Jacques Siclier was of the opinion that Gilda was revealing "the complexities and repressions of a society" "in which there is enormous emotional and sexual confusion". Even before Endstation Sehnsucht (1951), Gilda draws , "embedded in a harmless history of money and power, the portrait of the unsatisfied woman". In Sicler's opinion, the film was “sociologically a key film of the greatest importance”, which received “its moral consistency” through psychoanalysis in 1946 at the “height of the gender struggle on the screen”.

Geoff Mayer came to the conclusion that in view of the strict censorship at the time , Gilda was “a sexually provocative film” in which lewd topics such as sadomasochism and homosexual tendencies were hardly hidden. The film therefore continues the trend of film noirs such as Woman Without a Conscience (1944), who had previously addressed sexual desire as the driving force behind actions. But in contrast to Woman Without a Conscience or In the Net of Passions (1946), Gilda Frank Krutnik has "several significant differences in relation to the portrayal of women as erotic subjects". Furthermore, Krutnik described Gilda as the "best example of the suppression of male drama by the drama of female identity".

Sabine Reichel also found that “ Gilda through Rita is a dancing cult classic from the series”, in which the seductive woman, atypical for a film noir, no longer only appears as an object in the eyes of a man, but also has the opportunity to to show her vulnerability, which makes her appear human and sympathetic. Through this shift from object to subject, women could identify with Gilda or Hayworth and develop understanding for their actions, which according to Edward Z. Epstein and Joe Morella is a fundamental factor in their attraction. Even Adolf Meier Heinzl said: "Despite the negative light in Gilda first falls on the Hayworth image that gets the film to Rita's biggest hit; not least because it is multifaceted and surprising, pointing beyond the South Seas pin-up and confirms Rita in the role of the good-bad-girl in the happy ending. ”Because Gilda is contrary to that within a male milieu If the usual pattern of film noir proves to be the real heroine of the film, according to Philip Green, men are also forced to identify with her, which leads to "sexual discomfort" in the male audience due to the pleasure that Gilda simultaneously feels.

According to Marli Feldvoss, the “erotic signal from Rita Hayworth remains unchanged to this day when Gilda appears on the screen with that inimitable head movement and a meaningful look over her shoulder”, which is why Hayworth is “the only reason” “why Gilda is one today Cult film is ”.

References in other films

Just two years after the premiere, Gilda played a role in another film. In Vittorio De Sica's neorealist masterpiece Fahrraddiebe (1948), the day laborer Antonio Ricci finally got a permanent job as a poster sticker, for which he needed a bicycle. However, when he sticks his first poster, an Italian film poster with Rita Hayworth in a seductive pose as Gilda, on a wall, his bicycle is stolen. That moment when Antonio, fascinated by Gilda, fatally disregards his bicycle, becomes the film's key moment. De Sica also illustrated how much Italy was shaped by American Hollywood films after the war, and how this, with its glamor tending towards escapism , stood in stark contrast to the documentary, analytical style of the young Italian directors.

In the Italian comedy Die Gangster (1975), Hayworth is ultimately undoed as Gilda the protagonist, played by Marcello Mastroianni . Mastroianni plays Charlie, a gangster whose style is based on American crime films and who has been obsessed with Hayworth as Gilda since childhood. When he gets to know the prostitute Pupa, played by Sophia Loren , he absolutely wants to transform her into a Hayworth copy, which Pupa inevitably gets involved with. But when Charlie receives a girl named Anna in a huge cake in a huge cake, who looks even more like Hayworth, he ignores Pupa from now on. When he shoots Anna out of jealousy, Pupa sees to it that the police arrest him.

In Frank Darabont's famous prison film The Convicted (1994), based on Stephen King's novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption (1982), Hayworth as Gilda brings hope to Tim Robbins after he was innocently sentenced to life imprisonment as Andy Dufresne for the murder of his wife . Andy watches Hayworth's first scene of the film with other inmates in prison. While the others whistle and cheer, Andy asks his friend Red, played by Morgan Freeman , if he can get Rita Hayworth for him, which he receives from Red a short time later in the form of a pin-up poster. This poster then becomes a symbol of salvation by hiding Andy's escape tunnel that has been made over the years.

A Hayworth or Gilda poster is also prominently used in David Lynch's surreal thriller Mulholland Drive - Straße der Finsternis (2001) when a mysterious woman suffering from amnesia calls herself "Rita" after she saw Hayworth's name on the same poster in the mirror of a bathroom. In the dream-like film, which turns into a nightmare, the figure of Gilda symbolizes the archetype of the mysterious femme fatale , into whose role the film's Rita then slips.

In the romantic comedy Notting Hill (1999), Julia Roberts quotes Rita Hayworth in her role as film star with slightly different words - “They go to bed with Gilda, they wake up with me.” (Eng: “You go to bed with Gilda , they wake up with me. ") - and thus describes both Hayworth's dilemma and that of her role as the famous actress, onto whom men in particular project illusions that do not correspond to reality.

In the star-studded French crime comedy 8 Women (2002), two actresses pay tribute to Gilda and Hayworth respectively. Shortly after her appearance, Fanny Ardant performs a striptease as Pierrette, in which, like Hayworth, she suggestively strips off her black gloves. Isabelle Huppert initially appears as inconspicuous Augustine before she transforms into a beauty who wears her red hair loose and curly like Hayworth and is dressed in a glamorous strapless robe with a large bow.

In 2009, Gilda was also used in Michael Jackson's This Is It . When Michael Jackson catches a glove by montage in a video for his song Smooth Criminal , which Hayworth throws into the audience as Gilda after Put the Blame on Mame , a chase begins.

German versions

In the first German-language dubbed version from 1949, produced by Ultra Film Synchron, Gilda was voiced by Til Klokow , which Rita Hayworth later dubbed in The Lady of Shanghai (1947) and King of the Toreros (1942). However, this version is considered lost. In 1979 Bavaria Film commissioned a new dubbing for the broadcast on German television, which was more closely based on the US original version. Hayworth was spoken by Marienhof star Viktoria Brams . This version was also used for the film's previous DVD releases. In a direct comparison with the original version, however, it becomes clear that the dialogue scenes in the German version from 1979 are underlaid with completely different music. This is probably due to the fact that the international tape, which contains all the sounds and the background music from the original film, was no longer available at the time. This is the rule for new and initial dubbing of older films for television.

| role | actor | Voice actor 1949 | Voice actor 1979 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gilda Mundson Farrell | Rita Hayworth | Til Klokow | Viktoria Brams |

| Johnny Farrell / narrator | Glenn Ford | Curt Ackermann | Rudiger Bahr |

| Ballin Mundson | George Macready | Reinhard Glemnitz | |

| Detective Maurice Obregon | Joseph Calleia | Wolfgang Eichberger | Holger Hagen |

| Uncle Pio | Steven Geray | Manfred Lichtenfeld | |

| Casey | Joe Sawyer | Wolfgang Hess | |

| German | Ludwig Donath | Erich Ebert |

literature

- Mary Ann Doane: Gilda: Epistemology as Striptease . In: Femmes Fatales. Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis . Routledge, Chapman and Hall, New York / London 1991, ISBN 0-415-90320-3 , pp. 99-118.

- Richard Dyer: Resistance Through Charisma: Rita Hayworth and Gilda . In: E. Ann Kaplan (Ed.): Women in Film Noir . British Film Institute, 1998, ISBN 0-85170-665-7 , pp. 115-122.

- Sabine Reichel: Bad Girls. Hollywood's evil beauties . Heyne Verlag, Munich 1996, 207 pages, ISBN 3-453-09402-6 .

- Adrienne L. McLean: Being Rita Hayworth. Labor, Identity, and Hollywood Stardom . Rutgers University Press, 2004, 288 pp., ISBN 0-8135-3388-0 .

- Alex Ballinger, Danny Graydon: The Rough Guide to Film Noir . Rough Guides, 2007, 312 pp., ISBN 978-1-84353-474-7 .

- Alain Silver, James Ursini: Film Noir Reader 4. The Crucial Films and Themes . Proscenium Publ / Limelight, 2005, 336 pages, ISBN 0-87910-305-1 .

- Frank Krutnik: In a Lonely Street. Film noir, genre, masculinity . Routledge, London / New York 1991, 284 pages, ISBN 0-415-02630-X .

- Jennifer Fay, Justus Nieland: Film Noir. Hard-Boiled Modernity and the Cultures of Globalization . Routledge, 2009, 304 pp., ISBN 978-0-415-45813-9 .

- Melvyn Stokes: BFI Film Classics: Gilda . Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, 96 pages, ISBN 978-1-84457-284-7 .

Web links

- Gilda in the Internet Movie Database (English)

- Gilda at Rotten Tomatoes (English)

- Gilda at Turner Classic Movies (English)

- Film review with original quotes on filmsite.org (English)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. Portrait of a Love Goddess . Berkley, New York 1982, pp. 152-153.

- ^ Frank Krutnik: In a Lonely Street. Film noir, genre, masculinity . Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2001, p. 51.

- ^ A b Bernard F. Dick: The Merchant Prince of Poverty Row. Harry Cohn of Columbia Pictures . The University Press of Kentucky, 199, pp. 67-68.

- ^ A b John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. Portrait of a Love Goddess . Berkley, New York 1982, pp. 136-137.

- ↑ "Rita and I were very fond of one another, we became very close friends and I guess it all came out on the screen." Glenn Ford quote. after John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. Portrait of a Love Goddess . Berkley, New York 1982, p. 153.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. Portrait of a Love Goddess . Berkley, New York 1982, pp. 159-160.

- ↑ a b Sabine Reichel: Bad Girls. Hollywood's evil beauties . Heyne Verlag GmbH, Munich 1996, p. 59.

- ^ Documentation The Lady with the Torch . In: Gilda . DVD, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment 1999.

- ↑ “I must say of all the things I ever did for movies, that's one of the few I can really look at on the screen right now and say: If you want to see a beautiful, erotic woman, this is it. It still remains first class. " Jack Cole quote. after John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. Portrait of a Love Goddess . Berkley, New York 1982, p. 157.

- ↑ $ 60,000 wardrobe . In: Life , February 4, 1946.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. Portrait of a Love Goddess . Berkley, New York 1982, p. 157.

- ^ Prudence Glynn: In Fashion. Dress in the Twentieth Century . Oxford University Press, 1978, p. 82.

- ↑ Sheri Chinen Biesen: Blackout. World War II and the Origins of Film Noir . The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, p. 148.

- ^ "Which is decadent and where the normal rules do not apply" Andrew Spicer: Film Noir . Pearson Education Limited, 2002, p. 102.

- ^ Frank Krutnik: In a Lonely Street. Film noir, genre, masculinity . Routledge, London / New York 1991, p. 252.

- ^ A b c Andrew Spicer: Film Noir . Pearson Education Limited, 2002, pp. 102-103.

- ^ Sabine Reichel: Bad Girls. Hollywood's evil beauties . Heyne Verlag GmbH, Munich 1996, pp. 56-63.

- ^ A b Philip Green: Cracks in the Pedestal. Ideology and Gender in Hollywood . The University of Massachusetts Press, 1998, p. 149.

- ^ Sabine Reichel: Bad Girls. Hollywood's evil beauties . Heyne Verlag GmbH, Munich 1996, p. 45.

- ^ A b Adolf Heinzlmeier : Rita Hayworth - Cover Girl . In: The Immortals of Cinema. The glamor and myth of the stars of the 40s and 50s . Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1980, pp. 92-93.

- ^ Sabine Reichel: Bad Girls. Hollywood's evil beauties . Heyne Verlag GmbH, Munich 1996, p. 63.

- ^ A b Raymond Borde, Étienne Chaumeton: A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941–1953 . City Lights Books, San Francisco 2002, p. 55.

- ^ A b c Mary Ann Doane: Gilda: Epistemology as Striptease . In: Femmes Fatales. Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis . Routledge, Chapman and Hall Inc., 1991, pp. 113-118.

- ^ Mark Bould: Film Noir. From Berlin to Sin City . Wallflower Press, London 2005, pp. 89-90.

- ↑ a b c d Jörn Hetebrugge: Gilda . In: Jürgen Müller (Ed.): Films of the 40s . Taschen, 2005, pp. 342-344.

- ^ Frank Krutnik: In a Lonely Street. Film noir, genre, masculinity . Routledge, London / New York 1991, pp. 50-51.

- ^ Raymond Borde, Étienne Chaumeton: A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941–1953 . City Lights Books, San Francisco 2002, p. XVI.

- ^ E. Ann Kaplan (ed.): Women in Film Noir . British Film Institute, 1998, p. 54.

- ↑ a b Sabine Reichel: Bad Girls. Hollywood's evil beauties . Heyne Verlag GmbH, Munich 1996, pp. 55-56.

- ↑ a b Geoff Mayer: Gilda . In: Geoff Mayer, Brian McDonnell: Encyclopedia of Film Noir . Greenwood Press, 2007, 195-196.

- ↑ Sheri Chinen Biesen: Blackout. World War II and the Origins of Film Noir . The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, p. 150.

- ^ Nick Lacey: Image and Representation. Key Concepts in Media Studies . Palgrave, New York 1998, p. 30.

- ↑ Alex Ballinger, Danny Graydon: The Rough Guide to Film Noir . Rough Guides, 2007, p. 91.

- ^ Mary Ann Doane: Gilda: Epistemology as Striptease . In: Femmes Fatales. Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis . Routledge, Chapman and Hall Inc., 1991, pp. 104-107.

- ↑ Gerald Peary: Rita Hayworth. Your films, your life . Heyne, Munich 1981, p. 128.

- ^ Wheeler W. Dixon: The Early Film Criticism of François Truffaut . Indiana University Press, 1993, p. 129.

- ↑ Nicholas Christopher: Somewhere in the Night. Film Noir and the American City . Counterpoint, 2006, p. 141.

- ↑ Marsha Children: Refiguring Spain. Cinema, media, representation . Duke University Press, 1997, p. 48.

- ^ Valerie Orpen: Film Editing. The Art of the Expressive . Wallflower Press, London 2003, pp. 89-92.

- ↑ cf. boxofficereport.com ( Memento from June 24, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b Edward Z. Epstein, Joe Morella: Rita. The Life of Rita Hayworth . Comet, 1984, pp. 107-108.

- Jump up ↑ Bosley Crowther : Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford Stars of 'Gilda' at Music Hall . In: The New York Times , March 15, 1946.

- ↑ Deutschlandfunk : Calendar sheet , June 30, 2016, cf. Dagmar Röhrlich : The American atomic bomb tests began seventy years ago on deutschlandfunk.de on July 2, 2016.

- ↑ Bill Geerhart: Rita Hayworth and the Legend of the Bikini Bombshell ( Memento from September 21, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) on knol.google.com, July 14, 2010.

- ↑ John Kobal: Rita Hayworth. Portrait of a Love Goddess . Berkley, New York 1982, p. 257.

- ^ A b Kathleen M. Vernon: Reading Hollywood in / and Spanish Cinema. From Trade Wars to Transculturation . In: Marsha Children: Refiguring Spain. Cinema, media, representation . Duke University Press, 1997, pp. 49-50.

- ↑ David Forgacs, Stephen Gundle: Mass Culture and Italian Society from Fascism to the Cold War . Indiana University Press, 2007, p. 163.

- ^ Duncan Garwood: Rome . Lonely Planet, 2006, p. 224.

- ↑ Elke Rudolph: On behalf of Franco: "Films of International Interest". On the political instrumentalization of Spanish film in the 1960s . Lit Verlag, Hamburg 1999, p. 91.

- ↑ “Miss Hayworth, who plays in this picture her first straight dramatic role, gives little evidence of a talent that should be commended or encouraged. She wears many gowns of shimmering luster and tosses her tawny hair in glamorous style, but her manner of playing a worldly woman is distinctly five-and-dime. […] Glenn Ford shows, at least, a certain stamina […]. Charles Vidor, who directed; Virginia Van Upp, who produced for Columbia, and a trio of writers deserve no credit at all. They made out of Gilda a slow, opaque, unexciting film. " Bosley Crowther: Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford Stars of 'Gilda' at Music Hall . In: The New York Times , March 15, 1946.

- ^ “ Gilda is the result of ambrosial Rita Hayworth's desire to prove that she can act. [...] she proves that she is such a looker that nothing else much matters. " See The New Pictures ( February 19, 2011 memento in the Internet Archive ). In: Time , April 1, 1946.

- ↑ “Hayworth is photographed most beguilingly. The producers have created nothing subtle in the projection of her s. a. [...] The direction is static, but that's more the fault of the writers. " See Gilda . In: Variety , 1946.

- ↑ “The characters of the drama are interesting and well enough played and although the story has all the elements of high class trash, director Charles Vidor and his experienced players have given it considerable holding power, by keeping the audience in suspense from one dramatic shift to another. " Kate Cameron quote. after Gene Ringgold: The Films of Rita Hayworth . Citadel Press, Secaucus 1974, p. 163.

- ↑ Kim Newman : Gilda . In: 1001 films. The best films of all time . Steven Jay Schneider (Ed.), 2nd edition, Edition Olms AG, Zurich 2004, p. 230.

- ↑ “Highly charged story of emotional triangle […] unfortunately cops out with silly resolutions. Rita has never been sexier. " Leonard Maltin cf. tcm.turner.com

- ↑ "That sequence [...] established Gilda as a noteworthy work of erotically charged film noir, despite the Code-friendly, good-girl ending." Lucia Bozzola cf. omovie.com

- ↑ " Gilda is a wonderfully perverse noir classic that comes over as a cross between Casablanca […] and Hitchcock's Notorious ." Philip French : Gilda - review . In: The Observer , July 24, 2011.

- ^ “Charles Vidor's classic melo-noir Gilda from 1946 looks like the crazy evil twin of Michael Curtiz's Casablanca . [...] A real 1940s Hollywood treat. " Peter Bradshaw: Gilda - review . In: The Guardian , July 21, 2011.

- ^ Andreas Kilb : When Men Hate ( Memento from June 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive ). In: Die Zeit , July 29, 1988.

- ↑ Big cat . In: Der Spiegel , July 25, 1988.

- ↑ Gilda. In: Lexicon of International Films . Film service , accessed September 26, 2018 .

- ↑ cf. prisma.de

- ↑ cf. cinema.de ( Memento from September 29, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Official Selection 1946: In Competition ( Memento of June 1, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) on festival-cannes.fr ( Cannes International Film Festival ).

- ↑ Greatest American Movie Poster Classics on practical-home-theater-guide.com, December 17, 2012.

- ↑ AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Songs on afi.com ( American Film Institute ), 2004.

- ↑ “an almost unclassifiable movie in which eroticism triumphed over violence and strangeness” Raymond Borde, Étienne Chaumeton: A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941–1953 . City Lights Books, San Francisco 2002, p. 56.

- ↑ “Outstanding titles in the history of cinema” Raymond Borde , Étienne Chaumeton: A Panorama of American Film Noir, 1941–1953 . City Lights Books, San Francisco 2002, p. 67.

- ↑ Marli Feldvoß: Speaking of Rita Hayworth . New Critique, Frankfurt am Main 1996, pp. 97-98.

- ↑ " Gilda represents several significant departures from these other films in regard to the representation of the woman as erotic subject." Frank Krutnik: In a Lonely Street. Film noir, genre, masculinity . Routledge, London / New York 1991, p. 248.

- ↑ " Gilda is perhaps the most striking example of such a displacement of masculine drama by a drama of female identity." Frank Krutnik: In a Lonely Street. Film noir, genre, masculinity . Routledge, London / New York 1991, p. 197.

- ↑ "sexual unease" Philip Green: Cracks in the Pedestal. Ideology and Gender in Hollywood . The University of Massachusetts Press, 1998, p. 150.

- ↑ Marli Feldvoß: Speaking of Rita Hayworth . New Critique, Frankfurt am Main 1996, p. 8.

- ^ Giorgio Bertellini: The Cinema of Italy . Wallflower Press, London 2004, p. 87.

- ↑ Jennifer Fay, Justus Nieland: Film Noir. Hard-Boiled Modernity and the Cultures of Globalization . Routledge, 2009, p. 86.

- ↑ Donald Dewey: Marcello Mastroianni. His Life and Art . Carol Pub. Group, 1993, p. 216.

- ^ Tony Magistrale: The Films of Stephen King. From Carrie to Secret Window . Palgrave Macmillan, 2008, p. 103.

- ^ Roger Ebert : Mulholland Drive . In: Chicago Sun-Times , October 12, 2001.

- ↑ Ed Kellerher: Notting Hill ( Memento of the original from September 30, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: Filmjournal International , November 2, 2004.

- ^ Katja Schumann: Film genres: crime film . Reclam, 2005, p. 355.

- ↑ Manohla Dargis : The Pop Spectacular That Almost Was . In: The New York Times , October 29, 2009.

- ↑ Synchronization from 1949: Gilda in the German synchronous index

- ↑ Synchronization from 1979: Gilda in the German synchronous file

- ↑ Thomas Bräutigam : Stars and their German voices. Lexicon of voice actors . Schüren Verlag, Marburg 2009, p. 39.