Madame X (painting)

|

| Madame X |

|---|

| John Singer Sargent , 1883/1884 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 208.6 × 109.9 cm |

| Metropolitan Museum of Art , New York |

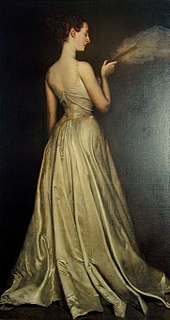

Madame X , Madame Pierre Gautreau or Portrait of Madame X is the informal title of a portrait by John Singer Sargent . It depicts Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, a young society lady. She was born in the United States, came to France as a four-year-old half orphan with her mother and older sister, and as a young woman married the wealthy French banker and shipowner Pierre Gautreau. In Paris society, she was known for her beauty and her alleged extramarital relationships.

The portrait of Madame X was not a commissioned work, but came about at Sargent's explicit request. This resulted in a study of opposites. Sargent painted a woman in a low-cut satin black dress with jeweled straps that contrasted strikingly with her pale skin tone.

The portrait was exhibited at the Salon de Paris in 1884 and received controversy. With a successful portrait exhibition, Sargent had hoped to establish himself as a portraitist in France. Indirectly, this failure led Sargent to focus on British and US clients, establishing himself as a portraitist in the UK and the US. Madame X is one of the last paintings to be created during Sargent's Paris period.

background

Virginie Gautreau

Virginie Gautreau (1859-1915) was born in the US state of Louisiana . Her mother was Marie-Virginie de Ternant, supposedly the only surviving child of the Marquis de Ternant. Her father, Major Anatole Placide Avegno, died in 1862 as a result of the wounds he suffered during the Battle of Shiloh . The widowed Marie-Virginie de Ternant returned to France shortly after the death of her husband with the then four-year-old Virginie and her older sister Julie.

In French society, Marie-Virginie de Ternant and her daughters remained largely outsiders; de Ternant's aristocratic lineage was too questionable, her background too mysterious, to gain access to the highest levels of French society. Virginie's marriage to the wealthy banker and shipowner Pierre Gautreau did nothing to change that.

Virginia Gautreau was not a beauty in the classical sense. Her figure with the narrow waist corresponded to the ideal of beauty of the time, but her nose was too big, her chin too protruding, the hairline too far from the forehead and the lips too narrow. In combination, however, this resulted in an extraordinary appearance that Virginia Gautreau was very aware of. She used large amounts of powder to emphasize the paleness of her body skin, and Sargent's biographer Olson believes it is possible that she also used small amounts of arsenic to achieve that skin color. In public she was considered a typical representative of the Parisienne , a new type of woman that stood out for her sophistication and sophistication. The term professional beauty - a term used to describe women who achieved social status due to their appearance - was also used for them. Their unconventional appearance ensured that a number of artists became aware of them. The American painter Edward Simmons claimed that he couldn't stop stalking her like a deer.

John Singer Sargent

John Singer Sargent was also impressed by Virginie Gautreau and assumed that a portrait of her in the upcoming Salon de Paris would attract a lot of attention and subsequently get him a number of commissions. He had met Virginie Gautreau in the early 1880s and shortly afterwards wrote to a friend:

“I have a great desire to portray her and have reason to believe that she would allow it and is actually just waiting for someone to suggest this homage to her beauty. If you get on well with her and meet her in Paris, then maybe you could tell her that I am a man with tremendous talent. "

In 1883, the 27-year-old Sargent was primarily driven to establish himself as a portraitist. He began his training as a painter at the age of 13 with the German-American painter Charles Feodor Welsch and, at the age of 18, became a student of Carolus-Duran in Paris . After traveling through Europe, he now had to assert himself on the art market. With paintings such as El Jaleo and The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit , he achieved considerable success in the Salon de Paris. So far, however, he has only received his portrait commissions from his circle of friends. That changed at the beginning of 1883 when Margaret Stuyvesant Rutherford White, wife of the US diplomat Henry White , commissioned him to do a portrait.

The White couple had first seen his paintings in the Salon de Paris; Her impression of Sargent's Portrait of a Lady with a Rose was decisive for Margaret White's portrait commission . The job of the socially well-connected American promised an advertisement for Sargent that far outshone his success in the Salon de Paris.

Sargent was already working on the portrait of Mrs. Henry White when Virginie Gautreau, who had previously turned down similar requests from other artists, accepted Sargent's offer in February 1883. It is believed that their collaboration was also motivated by the common goal of being recognized in French society.

Preliminary studies

Sargent had originally assumed that it would only take him three weeks to complete the portrait. During the first few months of 1883, however, Sargent made little progress. Gautreau had numerous social responsibilities and did not have the discipline and patience to model Sargent for long. At her suggestion, Sargent traveled to her country estate in Brittany in June of that year , where he drew and painted a series of preliminary studies.

As before in Paris, Virginie Gautreau turned out to be an undisciplined model: she was bored of sitting still. She also had a number of social responsibilities in the country: she had to look after her four-year-old daughter, her mother, and her guests, and she had to lead her many domestic workers. Sargent repeatedly complained about both the painterly elusive beauty of the young woman and her hopeless unwillingness to be portrayed.

Sargent's biographer Olson shows understanding for Madame Gautreau's displeasure, because Sargent was initially unable to find a suitable pose for his portrait. A total of 30 drawings and oil sketches exist from this period. Sargent drew them sitting in a twisted posture, with his head up, looking at a book, playing the piano, looking out of a window and finally standing at a table with a champagne glass in his hand. This oil sketch Madame Gautreau brings out a toast , which is now in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum , shows the sitter in profile and with bare arms against a dark background and is therefore very close to the final portrait. However, it is characterized by a more generous brushstroke and is clearly a pure study. Finally, Sargent asked Gautreau to pose while leaning one hand on an empire table , and determined that pose for the final portrait.

execution

Sargent had already successfully exhibited two works at the Salon de Paris. He had chosen very large canvas formats for both The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit and El Jaleo , because a very large number of tightly hung paintings were shown in the Salon de Paris and large-format paintings had a greater chance of both the public and the critics and get noticed by the award committee. For his portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau, too, Sargent chose an unusually large format: it is more than two meters high and over a meter wide.

The pose of his model differed from those that his sitters had previously assumed; Gautreau turns her body head-on to the viewer, she leans on the low table with her right arm stretched backwards, gathers the skirt of her black satin dress with her left hand and at the same time turns her head to the side. This posture adds tension to the pose, shows Gautreau's famous profile and emphasizes her elegant body shape. It expresses self-confidence, assertiveness and restraint at the same time. The unnaturally pale skin tone, the narrow waist and the severity of the profile underline her belonging to the uppermost social class, but also give the portrait a detached, controlled erotic look. The neckline of the dress was daring according to the conventions of the time. In the original version shown in the Salon de Paris, the erotic charisma of the portrait was underlined by the fact that the right strap had slipped over the shoulder. A critic of the French newspaper Le Figaro wrote at the time that the picture looked as if it only needed one more movement and the lady had been freed from her dress. Sargent painted over the position of the porter after the exhibition was over.

Sargent used a color palette for the painting that is dominated by white lead , madder , vermilion , viridian green and ivory black . The table leg on the left edge of the picture, on which some light falls, gives the portrait depth. The body silhouette of Virginie Gautreau is reflected in the shape of the table. The paleness of the face, shoulders, neck and arms contrasts strongly with the shimmering brownish background and the black satin dress. What is striking, however, is her reddish ear - in the words of art historian Elizabeth Prettejohn, an irritating reminder of the color of bare skin.

Art critics today assume that the figure's posture was inspired by a fresco by Francesco Salviati . Sargent makes subtle references to classic models: sirens adorn the table legs and the tiara that Gautreau wears symbolizes Diana , the goddess of the hunt. The latter, however, was not deliberately chosen by Sargent, but part of Gautreau's self-staging.

The Salon de Paris in 1884

Virginie Gautreau was very enthusiastic and convinced that a masterpiece was emerging during the time that Sargent was working on the portrait. Sargent himself, however, began to have doubts as the salon opened in 1884. He wrote to a friend that his former teacher Carolus-Duran had predicted success for the picture at the upcoming exhibition, but added, half-jokingly, that he would prefer it not to be accepted by the selection committee. But that wasn't to be expected. Sargent, who has already been awarded at previous exhibitions, was part of the so-called hors concours , those artists who were allowed to choose their exhibited pictures themselves, regardless of whether they were approved by a selection committee.

Sargent's concerns resulted not only from the daring portrayal of his model, which ultimately did not flatter her. Overall, the picture was kept in rather monochrome tones, the brushstroke more elaborate than in previous paintings by Sargent. When the salon finally opened, the public and the press reacted negatively and took great offense at the portrait. One day after the exhibition opened, his friend Ralph Curtis wrote to his parents:

“John ... was very nervous about his fears, but yesterday's events far exceeded his fears. There was a huge spectacle all day before him [the portrait]. After a few minutes I found him hiding behind doors to avoid friends who looked very serious. He led me down the hall to show me. I was disappointed with the color. It looks decomposed. All women mock. Ah voilà , la belle! , oh source horreur! etc. Then a painter calls out: superbe de style , magnifique accuracyace! , quel dessin! ... The whole morning was nothing more than a string of bon mots , bad jokes and angry discussions. John, the poor boy, was devastated ... In the afternoon the mood changed, as I had been predicting all along. It was discovered that as a connoisseur one had to speak of étrangement épatant [a great oddity]. "

The portrait was shown under the title Portrait de Mme *** ; the attempt to preserve the anonymity of Virginie Gautreau, however, failed because of her fame. On the day the exhibition opened, Virginie Gautreau went to Sargent's studio to ask Sargent to withdraw the portrait. Instead of Sargent, she only met his friend Curtis. Gautreau's mother later returned to the studio, this time running into Sargent and making a scene for him, complaining that all of Paris was rubbing off her daughter. Sargent refused, pointing out that the regulations of the Salon de Paris forbade it to withdraw a painting. Among other things, he defended himself by saying that he had painted Virginie Gautreau exactly as she dresses and that nothing could be said about the painting that was not already rumored about its appearance.

Sargent's biographer Olson points out that the Sargent portrait scandal was aimed less at the portrait than at the person being portrayed. Nevertheless, the scandal was a major setback for Sargent. After his portrait of Mrs. Henry White, he had been able to hope to achieve a breakthrough on the French art market with another success, a hope that in the spring of 1884, in his opinion, had been dashed. Olson also points out, however, that Sargent had only seen successes up to this point and that his departure from Paris was in many ways an overreaction.

Aftermath

Sargent did not spend the summer of 1884 in Italy, but went to London at the request of his friend Henry James . There he was still largely unknown despite the portrait of Mrs. Henry White , which portrayed the wife of the US diplomat Henry White, who worked in London and which was shown in the Royal Academy exhibition in 1884. In London, however, he succeeded in gaining a new clientele. His first work in London, The Misses Vickers , featured the daughters of the industrialist Vickers. Orders from similar customers followed.

Seven years after Sargent's portrait was made, Virginie Gautreau was painted by Gustave Courtois . This portrait also shows her in profile, her white dress is cut out no less than the one in which Sargent painted her, and here too - as originally in the portrait from 1884 - the wearer has slipped over her shoulder. However, this picture was received more favorably. Another portrait by Antonio de la Gandara from 1898, a back view in which the person portrayed only shows the viewer in profile, is considered to be the one that Virginie Gautreau valued the most.

Provenance

Sargent changed the name of the painting to Madame X after the exhibition . The name suggested more than the original title Portrait of Mme *** that an archetype of a woman is represented here. The painting first hung in Sargent's Paris studio and later, after he moved, in his London studio. Starting in 1905, he showed it at several international art exhibitions. In 1916 he finally sold it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art , which still includes it. It is shown in Gallery 771 today. In the same room there is also Sargent's portrait of a lady with a rose . After Madame X was sold , Sargent wrote to the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art: I think it's the best thing I've ever done. A second, incomplete version is in the Tate Gallery , London.

Gallery of Studies on Madame X

See also

literature

- Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 .

Single receipts

- ↑ Kilmurray, Elizabeth and Ormond, Richard: "John Singer Sargent" Tate Publishing Ltd, 1999. ISBN 0-87846-473-5 . P. 101.

- ↑ Ormond, 1999. p. 28.

- ^ Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 101.

- ^ Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 , p. 102.

- ↑ Elizabeth Prettejohn: "Interpreting Sargent," Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1998. ISBN 978-1556707285 . P. 25.

- ↑ Deborah Davis, "Sargent's Women". Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , p. 14.

- ↑ Deborah Davis: Sargent's Women. Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , p. 15, and Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 , p. 102. The original quote is: I have a great desire to paint her portrait and have reason to think she would allow it and is waiting for someone to propose this homage to her beauty. If you are 'bien avec elle' and will see her in Paris, you might tell her I am a man of prodigious talent.

- ↑ Deborah Davis, "Sargent's Women". Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , pp. 14 and 15

- ^ A b c Elizabeth Prettejohn: "Interpreting Sargent", Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1998. ISBN 978-1556707285 , p. 26.

- ^ Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 103

- ↑ Deborah Davis, "Sargent's Women". Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , p. 16.

- ↑ Deborah Davis, "Sargent's Women". Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , pp. 16 and 17.

- ↑ engl. Original title: Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast

- ^ Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 103

- ↑ Deborah Davis, "Sargent's Women". Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , p. 17.

- ↑ Kilmurray, Elaine and Richard Ormond (Eds.): John Singer Sargent . Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1998, ISBN 0-691-00434-X . , P. 101

- ↑ Kilmurray, Elaine and Richard Ormond (Eds.): John Singer Sargent . Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1998, ISBN 0-691-00434-X . , P. 101

- ↑ Deborah Davis, "Sargent's Women". Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , p. 18.

- ^ Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 103.

- ↑ quoted from Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 103. In the original, the excerpt from the letter reads: John ... was very nervous about what he feared, but his fears were far exceeded by the facts of yesterday. There was a grand tapage before it all day. In a few minutes I found him dodging behind doors to avoid friends who looked grave. By the corridors he took me to see it. I was disappointed in the color. She looks decomposed. All the women jeer. Ah voilà , la belle! , oh source horreur! etc. Then a painter exclaims superbe de style , magnifique accuracy! , quel dessin! ... All the am it was one series of bon mots, mauvaises plaisanteries and fierce discussions. John, poor boy, was navré ... In the p.am. the tide turned as I kept saying it would. It was discovered to be the knowing thing to say étrangement épatant !.

- ↑ Ma rille est perdu - tout Paris se moque d'elle. Quits after: Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 104.

- ↑ Ormond, R., & Kilmurray, E .: "John Singer Sargent: The Early Portraits," Yale University Press, 1998, p. 114

- ^ Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 105.

- ^ Stanley Olson: John Singer Sargent - His Portrait . MacMillan, London 1986, ISBN 0-333-29167-0 . P. 111.

- ↑ Deborah Davis, "Sargent's Women". Adelson Galleries, Inc., 2003. ISBN 0-9741621-0-8 , p. 20.

- ↑ Prettejohn, p. 27. The original quote is: I suppose it is the best thing I have ever done.

- ↑ Kilmurray, 1999. p. 102.