Très Riches Heures

The Duke of Berry's Book of Hours ( French: Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry or Très Riches Heures for short ) is the most famous illustrated manuscript of the 15th century. It is an extremely richly decorated book of hours containing 208 sheets of 21.5 cm wide and 30 cm high, about half of which are full-page illustrated. Because of its splendid furnishings and artistic execution, the book is one of the greatest masterpieces of book illumination . In particular, the calendar sheets also have a high documentary value for knowledge of the ways of life and views of the time. The original manuscript is now in the Musée Condé in Chantilly Castle , but can only be viewed as a facsimile , except by prior arrangement for specialist scholars .

The book of hours was painted between around 1410 and 1416 by the Limburg brothers for their employer, Johann von Berry , but was not completed because both their employer and the three brothers Johan, Paul and Hermann died in 1416 (possibly a plague epidemic ). Duke Charles I of the House of Savoy commissioned Jean Colombe to complete the paintings. The manuscript was completed between 1485 and 1489.

In 1975, shortly after the publication of Millard Meiss ' third volume on Painting in the time of Jean de Berry (1974), Bellosi was the first to point out that another artist also contributed to its completion around the middle of the 15th century must, whom Edmond Pognon gave the name "Master of Shadows" and who is still not clearly identified. Possibly it is Bartholomäus van Eyck , but this was last doubted by Reynolds. The extremely richly furnished work contains numerous very humorous allusions in the marginal drawings. For example, in the lower left corner of the sheet “Visitation of Mary” a pig sitting on a wheelbarrow can be seen playing the bagpipes , a knight is fighting a snail, and on the lower edge a priest is trying to catch birds with a liming rod .

The client, Duke of Berry

John of Berry was the third son of John the Good , King of France . His brothers were the French King Charles V and the Duke of Burgundy , Philip II. Jean Duc de Berry is one of the greatest art patrons in history . Numerous churches and castles were restored or rebuilt in his domain during his lifetime. His passion for collecting was valuable jewelry , rarities from nature, portraits of contemporaries and especially books of hours .

Meaning and structure of the calendar sheets

The calendar pages have become the main thing in this book of hours : The Très Riches Heures are one of those rare manuscripts in which each picture of the month takes up an entire page of its own. In addition, through them we learn a lot about the ways of life and views of the time. While the usual books of hours depict the seasons and monthly work rather symbolically, the full-page pictures of the Très Riches Heures show the typical activities for each month in front of a landscape shaped by the respective season. In the background, one of the castles of the duke or the French king can usually be seen in a historically accurate representation.

Each image is crowned by a bezel . This shows in an outer arc in blue camaieu the zodiac signs assigned to the respective month in monochrome blue against the background of golden stars. Below that, a semicircle shows the ruling planetary deity , also depicted in a blue camaieu as a man who presents a shining sun like a monstrance on a chariot pulled by two horses. The prototype for this sun chariot comes from a medal that is in the Bibliothèque Nationale today and depicts Emperor Heraclius bringing the true cross to Jerusalem . A copy of this coin also belonged to the collection of the Duke of Berry.

These lunettes were all created by the Limburg brothers, possibly all at the same time, because even the November leaf, which was later entirely painted by Jean Colombe , shows a lunette that exactly matches the others. On the other hand, the astronomical - astrological information, which frame the signs of the zodiac and the planetary deity in a semicircle and make the calendar sheets a calendar in the true sense, were not entered on all sheets; only the golden grid is already given everywhere.

The individual calendar sheets

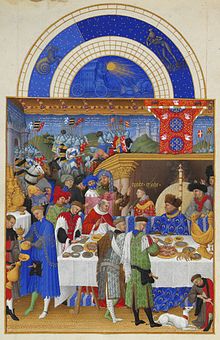

January

During the lifetime of the Limburg brothers , the month of January was indicated by depicting the double-headed god Ianus in a medallion . The Limburg brothers took up this motif in their calendar sheet and modified it slightly.

The role of Janus has been taken on by the Duc de Berry, the commissioner of the painter himself, who turns his profile towards the viewer . He is wrapped in a bright blue robe that was painted in precious ultramarine blue , the Duke's favorite color.

The bench on which the Duke has taken his seat is also blue. There is only one other person sitting next to him - albeit at a proper distance. It probably depicts Martin Gouge de Charpaigne, Bishop of Chartres , who was one of the Duke's preferred interlocutors and how he was a great friend of elaborate manuscripts and illuminations.

The special role that the Duke plays on this calendar sheet is also emphasized by the wall screen , which is supposed to protect him from the heat of the fire. The screen looks like a halo , against whose yellowish color the duke's blue robe and fur hat stand out effectively. Directly above the screen is a canopy , on the red background of which you can see the blue coat of arms of the lily and the duke's two heraldic animals, the swan and the bear. The combination of the golden fleurs de lys on a blue background (the traditional symbol of the crown of France) with the duke's personal heraldic animals identify him as a member of the royal family.

A master of ceremonies liveried in the colors of the canopy summons those who have been admitted to the New Year's reception. Those entering raise their palms to the fire to warm themselves: a gesture that was so natural in the Middle Ages that the fire itself was not needed as an explanation or, as here, was only hinted at. (The straw mats on the floor are also supposed to protect against the cold.) Among the newcomers are two men with gray woolen hats . They could be (self) portraits of Paul von Limburg (right) and one of his brothers. Behind the Duke, a young man leans casually on the back of the bench. This gesture demonstrates confidentiality; it is likely to be a relative of the duke, or at least a young prince from his retinue. However, the identity of the person depicted has not yet been clarified.

At the right edge of the picture is a typical medieval table device , a so-called salt ship . This table utensil is described in detail in the Duke's inventory and is also crowned by a bear and a swan . The counterpart to the salt ship is on the left edge of the picture. There, the showboard shows other equipment from the Duke's gold and silver chamber and, underneath, two courtiers who handle individual equipment. Such cups, bowls, etc. were not only used on the table, but were also popular as gifts. They were used to reward, sometimes also to pay for, and it is conceivable that the conspicuous display on the shelf on the left on the occasion of this New Year's reception can be seen in such a context.

The tapestry that closes the room at the back shows - as the incompletely decipherable text shows - a scene from the Trojan War , executed in the costumes from the time the sheet was created around 1400 ('historical' representations only prevail later).

February

In clear contrast to the courtly pomp of the January newspaper, February is depicted with a scene from the life of the common people, more precisely from rural life. Almost 90% of the people at that time worked in agriculture; many were unfree in the most varied of regional forms.

Under the dark gray sky, the white, snow-covered landscape is all the more intensely and clearly contoured. In the background a snow-covered village crouches between the hills. A man with a donkey walks towards it, another man is chopping wood, and in the foreground is the traditional motif for February: a man warming himself by the fire.

The painter omitted the wall of the house so that one can watch the peasant couple and the elegant lady (whose presence requires explanation) how they - just like in the stately castle - raise their hands to the fire to warm them: the universal gesture in the cold season. The fire is the center of the house: cooking area, light and heat source at the same time. The peasant couple unabashedly pulls up their clothes to let the warmth into their bodies. The noble lady turns her head away: The rules of decency and shame are still dependent on class; they can probably only develop and be followed where people do not live quite as closely together as in the rural hut. The furnishing of the room contrasts with the stately castle in the January picture: there are no heat-insulating straw mats on the floor, laundry is hanging on the walls instead of valuable tapestries, and no household items are displayed.

Bundles of firewood can be seen outside. The big, sturdy logs belong in the chimneys of the rulers, the peasants only get what is left over. A figure, thickly hooded from the cold, strides towards the house. Smoke rises from the chimney.

The sheep huddle closely together. Hooded crows look for food in close proximity because they cannot find anything else in the frozen ground. The beehives are empty: they were fumigated in autumn, new colonies were only caught in spring ( honey was the most important sweetener at that time). The large structure, reminiscent of a watchtower , is a pigeon house : pigeons were also considered a delicacy in the Middle Ages. Even more important, however, was the use of their excrement as fertilizer .

Overall, the February leaf shows a natural sensation that was still very rare at that time.

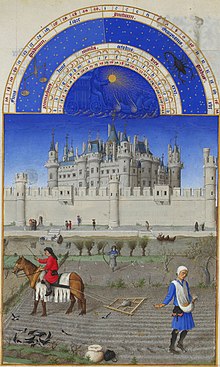

March

In the March picture, the Limburg brothers show the first farm work of the year by juxtaposing different scenes in an extensive landscape at the foot of the Château de Lusignan . Edmond Pognon suspects, however, that this sheet initially remained unfinished and was only completed around 1450 by an artist who was not identified in detail, what he called the "Master of Shadows".

Above left, a shepherd with his dog grazes his sheep. Below the traditional motif for March appears: the pruning of the vines , which is done here by three farmers. On the right edge of another clos , in which this work is already done, there is a small house. A farmer sifts grain into a sack underneath. A small structure in the center of the crossroads, known as the Montjoie , separates the different parts of the picture. (A similar motif can be found in the Meeting of the Magi , Folio 51v.)

The field is plowed in the foreground. An old farmer with a white beard controls the plow with his left hand while he steers the team of oxen with his right . The proportion of people who will reach the eighth decade of life at that time is estimated at around 10%. The two oxen are of different colors, the brownish skin of the animal in front stands out clearly from the black of the animal behind, which can only be seen in outline. Every detail of the plow is carefully reproduced. The ploughshare tears up the earth covered with dry winter grass; the furrows that have been drawn can be recognized by the already dried blades of grass.

This representation was already out of date when it was created: the wheel plow pulled by the much more powerful horse had largely supplanted the ox team since the 12th century. There may be two reasons why the outdated technology continues to appear in such a splendid illustration: on the one hand, the indifference at the time to what is of eminent importance today as " progress ", on the other hand the historically proven disinterest of the client Johann von Berry in the actual living conditions of the common people .

The rural scenes are dominated by the mighty Château de Lusignan, above which the fairy Melusine hovers in the form of a golden winged serpent. Mythical ancestor of those of Lusignan and patroness of the castle, which according to legend she built in a single night, she always appeared shortly before the castle changed hands. The artists have accurately reproduced the various parts of the château: the Tour Poitevine below the fairy, the residential buildings, the Tour Mélusine , the Tour de L'Horloge , the barbican and the double ring of walls. The Château de Lusignan was one of the Duke's favorite residences. However, it was initially occupied by the English and had to be besieged by its people for a long time. When they saw the winged serpent, it is said, they knew that victory was imminent.

The calendar page for the month of March is the first of the large landscapes that the Limburg brothers prefer in the Très Riches Heures . The terrain is represented with such great accuracy that it has been speculated that the brothers used optical instruments to achieve such precision of proportions. The delicacy of the brushstroke leads to an extraordinary level of detail without distracting from the magnificent palace complex, which towers mightily against the blue of the sky. Lusignan Castle was destroyed in 1575.

April

Against the backdrop of Dourdan Castle , property of the Duke since 1385 and expanded and fortified by him, the fields and forests turn green, flowers sprout from the fresh grass. The towers and the donjon , the remains of which have been preserved to this day, rise on a hilltop, in the immediate vicinity of which there is a village. The Orge , on which two boats can be seen (even if the representation looks more like a pond than a river) flows at her feet .

People in festive clothes are grouped in a rounded pyramid . Two girls bend down to pick flowers - violets perhaps - (April is the month of flower-picking on the calendar) while a bride and groom swap rings. The lavish items of clothing contrast effectively in the colors. The groom's princely clothes are decorated with golden crowns.

As everywhere, the details are carefully executed: the groom searches for the eyes of his fiancée while he puts the ring on her outstretched finger, which the bride in turn looks down on. The Limburg brothers have created a harmony of composition, colors and emotions that corresponds perfectly with the surrounding landscape and blossoming nature.

There are various historical interpretations for this representation. The view that it is the engagement of Charles d'Orleans to Bonne d'Armagnac, the daughter of Bernard VII d'Armagnac (to the right of Charles) and granddaughter of the Duke of Berry, in 1410 is hardly disputed . In this case the scene would be eminently political: During and after the so-called reign of the dukes for the mentally weak Charles VI. Two parties were formed which fought against each other in the civil war of the Armagnacs and Bourguignons against the backdrop of the Hundred Years War . In 1410, Berry's great-nephew Charles von Orleans allied himself with Berry's energetic son-in-law Bernard von Armagnac, after whom this party was finally named. It was customary to consolidate such alliances - if possible - through further family connections, as here too with the marriage of Charles and Bonne. Political advantage, war, misery and power struggles would be the real subject of this seemingly idyllic scene.

May

On the 1st of May - based on the ancient tradition of the Floralia - a cavalcade of young men and girls celebrates happily through the country and brings fresh green home. On this day you had to wear the “happy green”: people's heads or necks are wrapped in leaves. The foreground shows the dog rose it came from. In advance, five musicians with flutes, trumpets and trombones accompany the celebrants.

Jean de Berry liked to take part in these festivities when he was young. The king himself distributed articles of clothing to princes and princesses which - colored with malachite green - were called livrée de mai . In this picture they are worn by three young women. The lush flow of lines and the golden floral ornaments reveal that they are princesses or princesses.

Farther to the left, a man in an ornate blue robe with gold flowers is riding a gray horse with a red saddlecloth. Is it perhaps the Duke of Berry as a young man? At least that is what the small dogs - they have already been identified as Pomeranian lace - that frolic around the horse's hooves and are already known from the January newspaper suggest. Another rider, half dressed in red, the other half in black and white - the royal colors of that time - turns his head towards the young women. It may also be a prince. Between them rides the man with a large fur hat, who is also known from the January newspaper and has not been identified. The renewed spatial proximity to the Duke in connection with the similarity of clothing again suggests a close relationship; It is all the more regrettable that he has not yet been identified. In comparison with the chaos of the group of musicians, what is striking about the composition is the ascending line that forms the heads of the three princely horsemen, with the right head a little closer to the middle than the left, and its identical counterpart in the heads of the young women finds. Because of the unclear identity of the people, it cannot be decided whether this is just an artistic design feature or also a (hidden) social hint.

Roofs, towers and slender buildings can still be seen above the forest, which towers like a backdrop in the background. The scenery was initially considered to be the Château de Riom , capital of Auvergne and property of the Duke since 1360. However, it shows little in common with old views of the fortress. Rather, it is undoubtedly the Palais de la Cité in Paris, which can also be found in the June paper. The precise details - gables , chimneys, battlements and weather vanes - are part of the roof of the palace .

The rectangular tower on the left (with bay window) is therefore the Châtelet on the right bank of the Seine. After a gap, the tops of a corner tower follow, then those of the two towers of the Conciergerie , and finally the rectangular Tour de L'Horloge ( clock tower ). All four still exist today or again on the Île de la Cité . The towers of the Grand'salle adjoin further and, on the far right, the Tour de Montgomery (later called and destroyed in the 18th century) , seen from the rear. Accordingly, this scene takes place in the woods that began on the other side of the Rue du Pré-aux-Clercs , around what is now Rue de Bellechasse .

The pictures for January, April, May and August are apparently from the hand of the same artist.

June

The June picture shows the view from the Duke's city residence, the Hôtel de Nesle , to the Île de la Cité , the heart of old Paris. The Palais de la Cité was the residence of the French kings for three and a half centuries, but it was relocated a few decades before the miniature was made, not least for security reasons. The kings of the Berry period preferred the Hôtel Saint-Paul and the Louvre . The administration and in particular the jurisdiction remained on the Île.

The palace was already shown on the May sheet. This time it takes up the whole width of the picture and is much closer to the foreground. While in the previous picture only the background shows gables, roofs and chimneys, we are now almost in front of the buildings: on the left you can see the so-called Salle sur l'eau ; there is a real crowd on the stairs that lead up to her. This is followed by the Tour Saint-Louis (behind it; it was given the current name Bonbec much later) and the twin towers d'Argent and César of the Conciergerie , which are covered with red bricks instead of gray slate. All three burned down in the meantime, but were rebuilt in the 19th century. This is followed by the Tour de l'Horloge , the two gables of the Grand Salle behind the Logis royal , the Tour Montgomery (the round tower with a pointed roof in the center) and finally the Sainte-Chapelle with a cross on the spire. In front of these facades we see a garden that is partially covered by a curtain wall. The wall ends on the left in a gate that opens to the Seine . A boat on the river bank completes the scene.

The view from the Hôtel de Nesle - which now houses the right wing of the Institut de France , which houses the Bibliothèque Mazarine - includes not only the interior of the Palais de la Citè, but also a field on the left bank of the Seine. Well-to-do homes always had a garden or a field, but they were generally outside the city gates. Only the gardens of the really rich and powerful, to whom the Duke belonged, lay within the walls directly in front of the windows of their palace.

June is the haymaking month on the calendar . Farmers, perhaps also paid workers, with hats as sun protection and bare legs mow a meadow together. As well as the light clothing and - again as protection from the sun - the headscarves of the two hay tedders in the foreground, this suggests that it is a hot summer day. The details are also reproduced in great detail in this picture. The freshly mown grass stands out clearly from the more intense green of the uncut, the already faded yellow of the hay shows a different shade. Elegance and grace in the filigree fragility and the swing of the female figures in connection with the rustic coarseness of the male figures - as well as the rural activity as such - make up the charm of this scene.

July

The Limburg brothers depict the usual subject for farming activity in July in the middle distance : the grain harvest. This is not done with scythes like haymaking , but with sickles , and the stalks were not cut directly above the ground, but significantly higher so that enough straw remains for the cattle. It is made by two pawns on this hand. The one who is clearly reminiscent of the comparable figure in the June miniature is wearing a straw hat and a simple shirt, under which a pair of underpants becomes visible, which was then called petit drap . The wheat is shown exactly. The ears are more intensely golden than the stalks, which are interspersed with flowers at the edge of the field, which are likely to be cornflowers and poppies . The mown grain lies on the ground, not yet bound into sheaves, but already drier than the rest.

In the foreground on the right an unusual subject for July is shown, the sheep shearing : in the books of hours, if it occurs at all, it is usually shown instead of the hay harvest in June. A man and a woman each hold an animal by their knee. The wool is sheared with special scissors, called force . It gathers at the feet of the depicted. The usual explanation of the shearing people as a peasant couple may fall short. The woman's costume is strikingly reminiscent of that of the lady of the February newspaper: A black hood that stretches over the neck with distinctive tips, plus a blue dress, the excessive length of which should actually be called a train , in striking contrast to the realistically portrayed farmers of the middle distance, in any case does not correspond to peasant costume and is extremely impractical for the work shown. Could it be an early version of idealized country life, as it culminated almost 400 years later in the Hameau de la Reine ?

The scene takes place in the neighborhood of Château du Clain in Poitiers . The castle belonged to the royal family property. The town and castle were part of the Duke's apanage like the Berry or the Auvergne . However, he rarely visited Poitiers. Still, he was always extremely generous to the city. The crumbling castle was renovated, embellished and made more comfortable by him thirty or forty years before the miniature was made. The triangular complex was no longer used solely for defense, but for representation. The change from a castle to a palace is heralded. The illustration is a valuable testimony to the appearance of the chateau, which no longer exists.

It is viewed from the right bank of the Boivre River . A wooden footbridge , which rests on three stone bridge piers that stand in the river bed, leads to the right tower. The river landscape shows two swans and reed plants . The rectangular entrance tower is connected to the bank with a movable part that could be removed. At the other end, a drawbridge leads directly into the castle. On the right a chapel can be seen between various buildings, which are separated from the castle by a moat or a river arm. The towers are kept in the preferred by the Duke style, which is found in several of his palaces: machicolations (since the 19th century also machicolated called) between brackets, the defenders protectively by battlements, and provided in its upper part with tall, narrow windows . The castle remained the property of the duke until his death. It then briefly came into the possession of the Duke of Touraine before it fell to the future King Charles VII in 1417 , who made Poitiers one of his residences .

The background of the sheet is simple and conventional: asymmetrical mountain cones, as they were common in painting of the time. The miniature seems to have come from the same painter as the June sheet and was completed around 1450.

August

The scenery shows Étampes , which - like the nearby Dourdan since 1385 - has belonged to the Duke since 1400 and left by him to his great-nephew Charles d'Orléans . Both castles were captured by the Bourguignons ( Johann Ohnefurcht , a nephew of the duke) during the civil war in 1411 . It is therefore assumed that the miniature, at least the depiction of the castle, was already completed by this time. It is unlikely that the castle was presented to her case: first, were present at the siege of serious damage incurred, on the other hand, the the Duke loved above all and also in 1411 burned surfaced Bicetre not on the calendar pages, probably because it then to there was no corresponding template.

The Château of Étampes dominates the scene. You can clearly see the towers, the chapel and the parts of the building behind the walls . In the middle rises the Tour Guinette , a watchtower originally from the 12th century, the remains of which are still preserved today. The inventory that was drawn up after the Duke's death shows that he always enjoyed his stay in this place. He followed a family tradition that had already been founded by Hugo Capet .

In the foreground we see the beginning of a game hunt for game birds or haired game. A falconer with two griffins on his left fist, the heads of which are covered with small hoods, is pulling a long pole with his right, which was used to chase the game out of the bushes. To be a prince's falconer was a privileged position. He had to look after the rearing, care and training of the birds for hunting; Activities in which many princes actively participated themselves or for which they wrote detailed instructions.

The servant turns to the noble hunting party, perhaps to get instructions from the two couples and the single lady. The rider directly behind the falconer wears an ultramarine blue cape or cloak and a hat with an upturned brim. Another hawk sits on his gloved fist. The lady behind is dressed in a gray dress with a white flounce. The couple on the left on the brown horse seem to be engaged in a lively conversation, which - judging by the expression on their faces - is more of a personal nature than that of the upcoming hunt. The young man in the fur hat seems to be the same stranger who is already depicted on the January and May leaves. The single rider on her white horse wears an almost identical coat to the young man on the May sheet, in which the duke is generally assumed. Of course this is not a coincidence, but the reason is not known. As in May, the riders are accompanied by small dogs whose task here is to “point” (display) the game, whereupon the hoods are removed from the falcons and they are thrown to climb, with which the actual hunt begins.

The hunt with tamed birds of prey, especially falcons, was a particular passion of the nobility. Falcons or falconry were a status symbol. The animals also stood for friendship and harmony. In this sense, hawks were given away, offered as a prize in tournaments or used in betting. There were already wealthy urban citizens (whose wealth was no longer based on land ownership but on money) who could afford falcons, but in the traditional two-part world of the duke and his miniatures - here nobility, there peasants and farm workers - not yet arrived.

The different motifs of the miniature show for the first time a direct combination of court life and rural activities. On the hills behind the hunters, farmers tie freshly mown wheat into sheaves and load the harvest onto an already overcrowded cart. Bathers swim naked in the waters of the Juine . A woman, already undressed, is preparing to get into the water, another is just coming out. Two men swim in it. The deformation of the body caused by the refraction of light in the water is observed and reproduced with interest. The August miniature of this book of hours is presumably the only one that uses a hunting motif instead of the usual threshing subject for this month .

September

The depiction of the grape harvest at the foot of the Château de Saumur is striking because it apparently comes from different artists and was only completed by Jean Colombe . The different styles are evident in the coloring and painting technique as well as in the representation of the figures. Normally a miniature was started with the background: after the sky, landscape and buildings came the foreground, the people and finally the faces. Although a miniature was drawn out inconspicuously and only then colored in, the different styles are clearly recognizable here.

Saumur Castle near Angers did not belong to the Duke of Berry, but to one of his nephews, Louis II, Duke of Anjou , who had it built towards the end of the 14th century. This is a special case - all the other castles shown belonged to the duke or the king - and as such requires explanation; the mere family relationship is not sufficient for this. On the other hand, the extremely rich details with their golden finishes, which dominate for all the architectural precision, are striking, which in these miniatures only have a single equivalent in the October page and which clearly differ from the architectural representations of the earlier miniatures. The castle shines in unprecedented splendor: chimneys, pinnacles , weather vanes, crowned by golden fleurs-de-lis . The comparable sheet for October is generally attributed to the so-called "Master of Shadows", who may be Bartholomäus van Eyck . There is evidence that he worked for the Anjou around 1450 . According to this, the unfinished Book of Hours would have come into the possession of the Anjou after the Duke's death before it passed to the House of Savoy . However, this hypothesis has not been proven.

The castle still exists today. It belongs to the ensemble of the “ Loire castles ”. Although the glamorous crownings have disappeared, it remains clearly identifiable through its towers, parapets and battlements, as well as the general arrangement of the individual building parts. On the far left, a bell tower can be seen that may belong to the Saint-Pierre church. Next to it rises a monumental fireplace above the kitchen, strongly reminiscent of that of the nearby Fontevrault Abbey , and finally a drawbridge over which a horse has just come, and a woman with a basket on her head walking towards it. Saumur Castle remained neglected, neglected, and finally collapsed in parts, before it was partially restored in the 17th century as a barracks and later as a prison.

The free space in the center of the picture, bounded at the back by a wooden fence, is a tournament area with a barrier made of willow branches or reeds, the so-called tilt , which separated the knights charging against each other. The harvest scenes were carried out by Jean Colombe. Men and women fill the red grapes into small baskets, which in turn are emptied into larger baskets that are carried by mules or, loaded onto carts, pulled. At that time, wine was a staple food: the common people also drank it, sometimes several liters a day ( water was often contaminated and hazardous to health, milk too precious, fruit juice , coffee , tea unknown, and beer was just beginning its triumphal march out of the monastery breweries ).

The two mules in the sheet are clearly different in design. One of them may still come from the hand of the “master of shadows” or even from one of the Limburg brothers. In comparison, Jean Colombe's work seems far less sophisticated: the entire execution is clearly coarse and not very delicate, the colors are rather blurry and dull, the human figures compact and not elegant. For the first time in these calendar sheets we meet people who are more like caricatures. Country people - in contrast to the nobility - had to be ugly; a traditionalist U-turn that was already obsolete for the “master of shadows” and for the Limburg brothers one or two generations earlier . The people shown in the foreground appear very human and involuntarily funny. The worker in the lower left of the picture is licking the grape juice from his right hand, while the woman standing next to him throws her hands up in surprise because she sees the bare backside of the bending worker in the middle of the picture. Although he is a recognized miniature painter, the work of Jean Colombes does not stand up to any direct comparison with that of the other participating artists; especially here, where the difference in styles is evident on a single, common sheet. Nevertheless, this grape harvest as a whole is one of the most picturesque and beautiful sheets of the entire calendar.

October

October is the month for sowing winter crops . She is depicted here from the left bank of the Seine near the Hôtel de Nesle , the Duke's city residence, roughly from the same location as in the June miniature. In June, however, the Limburg brothers looked to the east, this time to the north. In June they gave back the former residence of the French kings, the Palais de la Cité , while now the Louvre can be seen, which had been the royal residence since Philippe Auguste , king from 1180 to 1223.

The imposing building of the Louvre in its form at the time of Charles V , who was an older brother of the Duke of Berry, looms before us . Thanks to the accuracy of the representation, every detail can be identified. In the center rises a huge tower, the Donjon built by Philippe Auguste . This tower, commonly known as the Tour du Louvre , had become a symbol of royal power over time. From here were apanages granted here, the state treasury was kept. In this depiction, the donjon covers the north-west tower , the Tour de la Fauconnerie , in which Charles V kept the most valuable manuscripts of his collection. For this we can identify other corner towers: on the right the Tour de la Taillerie , then the east facade, which is protected in the center by two towers, on the left the Tour de la Grande Chapelle as a corner tower and then the south facade , also protected by twin towers. The details are so precisely reproduced that centuries after the destruction of the building in its former form, a model could be created that is largely based on this representation.

A strong wall with towers, battlements, machicolations and a small gate protects the complex towards the Seine. Small figures walk along the quai , from which a few steps lead down to the river, which also serve as boat moorings. The clothes of the strollers in front of the wall correspond to the urban fashion of the middle of the 15th century and can be dated much more precisely than the traditional costume of the peasants, which has remained unchanged for a long time. Only one comparable figure can be found on these monthly pictures: the woman walking towards the castle in September.

The figures on this sheet are casting shadows for the first time - albeit only cautiously (like the old farmer in March). It is this suggestion, which is one of the earliest in Western art history, that earned the artist, who has still not been identified with certainty, the designation "master of shadows".

In the foreground, on the fields that meet the left bank, a farmer in a blue tunic is sowing seeds that he carries with him in a bag made of white cloth. A sack of seeds lies on the floor behind his back, where magpies and crows are already picking up the freshly spread seeds . In the field behind, a scarecrow in the shape of an archer, surrounded by a thin net with feathers, is said to keep the birds from attacking the sowing.

On the left a farmer on a horse is pulling a harrow , weighted down with a large stone, so that it penetrates deeper into the ground. Horses in the pictured tölt or pass gait ( tent ) were valued as quiet riding horses especially for women in the Middle Ages, but were rather uncommon as work animals, not least because of their high price. So it could again be a set piece from the world of the nobility in the rural environment. Overall, the scene in the shadow of the royal residence gives a vivid picture of life in the mid-15th century.

November

The sheet for November, which shows the pigs being driven into the forest, the acorn fattening , as the classic subject for this month, was completely executed by Jean Colombe. Only the bezel comes from the Limburg brothers and , as in all calendar pages, crowns the scenery with astrological signs in a semicircle. Its outer part shows the signs of the zodiac for November in monochrome blue against the background of golden stars: Scorpio on the left, Sagittarius on the right. It is possible that the lunettes for the different months were all created by the Limburgs at the same time.

In clear contrast to the other sheets, the November sheet no longer shows any stately castle or palace that is otherwise so proudly depicted by the artists. The original client Jean de Berry is long dead after all. The scenery, executed with a certain routine, seems to be a product of Jean Colombe's imagination, even if it may be inspired by the landscape of Savoy , in which he created the Très Riches Heures for the local Duke Charles I completed. The different levels are picturesquely arranged and lose themselves in a blue horizon in which a meandering river winds between mountains. Further ahead, the towers of a castle and a village nestle against the rocks. In the foreground, a farmer dressed in a reddish tunic pulls his arm back in order to throw a club into an oak tree and thus knock acorns. At his feet, pigs greedily eat the fallen fruit under the watchful gaze of a dog. Other farmers can be seen with their pigs under the trees. The entire scene is kept in muted colors, which at first glance distinguish it from the other monthly representations, without showing any loss of quality. However, the animals by no means show the physical strength that the “master of shadows” on the next page, the last of the calendar pages, knew how to give his creatures.

The pigs have found their place in the Très Riches Heures despite their negative connotation (they wallow in the mud). Nevertheless, they are part of daily life and make a significant contribution to people's nutrition. Pigs have been an integral part of the diet in Christian Europe over the centuries. Jean Colombe's peasant appears brutal and frustrated, in marked contrast to the earlier depictions. Nevertheless, his reddish tunic is illuminated by golden ornaments and light reflections.

The people of the Middle Ages liked to live in nature; but they did not transfigure it, as became customary since the Romantic era . They were much more directly dependent on it: the cold meant freezing, lightning strikes a fire hazard, a bad harvest meant hunger. The sheet was completed 60 years after the original commission. The colors are more matt; What is new, however, is the ability to create space and paint depth.

December

The circle closes. The towers in the background belong to Vincennes Castle , where Jean de Berry was born on the eve of December, November 30th, around a hundred years earlier. At that time the castle was far from having the dimensions shown here. The donjon , just started, consisted only of the foundations. The enormous rectangular complex with its nine towers was built from 1337 and essentially between 1364 and 1373 by Charles V , who was also called “sage artist, savant architecteur” (“wise artist, educated architect”) and the castle itself “La demeure de plusieurs seigneurs, chevaliers et autres ses mieux aimées” (“hostel of the nobility, knights and their best friends”), according to the formulation of his contemporary biographer Christine de Pizan (approx. 1365-1430).

As a result, Charles moved parts of his art collection, manuscripts and treasures here. Most of the towers pictured have been destroyed over the centuries. The entrance and donjon are best preserved. However, extensive restoration work has been carried out on the entire complex for over two decades .

The forests of Vincennes repeatedly attracted French kings. Louis VII built a hunting pavilion here. Philippe Auguste built a small castle, which was extended by Louis the Saint , who - as far as has been handed down - liked to hold his court days under one of the oaks there; Trees depicted in the red-brown colors of a passing autumn.

December is the month of the pig slaughter in the calendar pages, here ingeniously reinterpreted from a banal butcher scene to a hunting scene (the leaves on the trees have not fallen off either). The boar , brought down by the hunters with long spears, is torn to pieces by the dogs. Their ferocity is portrayed with remarkable realism. The expression, the position of the paws, the greed, the sheer strength, everything is carefully observed and reproduced. These are hunting dogs whose breed can be clearly assigned by connoisseurs. This sheet is also one of the liveliest in an altogether remarkable cycle.

The hunt for wild boars, bears, deer etc. was - even more so than the hawk or griffin hunt - the aristocratic sport par excellence. Here the superiority of physical courage, the nobility par excellence, was clearly expressed. It is all the more astonishing that this sheet does not show any noble hunters, but only peasant or servant hunters.

On the right one of them is blowing the halali on his horn . The hunt is over - and so is the year.

History and owner of the manuscript

Sometimes the assumption is expressed that the still incomplete manuscript passed the death Jean de Berry in the possession of his daughter Bonne and her husband Amadeus VII. Count of Savoy very quickly to the House of Savoy and finally Amadeus' direct descendants I. Karl arrived. However, this fails due to the fact that Amadeus died as early as 1391 as a result of a hunting accident and that Bonne was married to Count Bernard VII of Armagnac when her father died . However, in the inventory of the Duke of Berry's estate, which was drawn up in 1416, there appears the crucial reference by which the book and its painters could already be identified in the 19th century: “Item, en une layette plusieurs cayers d'unes tres riches Heures, que faisoient Pol et ses freres, tres richement historiez et enluminez ”(Several layers of a very rich book of hours in a box that was richly furnished by Paul and his brothers (note“ historier ”refers to the miniatures,“ enluminer ”to the rest Equipment of the book)). The much more probable assumption that the manuscript went through the library of the Anjou house, which also owned the Duke's Belles Heures , has not yet been confirmed. Recently, Nicole Reynaud assumed that Charlotte of Savoy owned the book of hours and given it to Charles I of Savoy.

What is certain is that Charles I of Savoy bequeathed the then completed manuscript in 1489 to his cousin Duke Philibert II (Philibert the Beautiful), who left it to his widow Margaret of Austria when he died in 1504 . This, at that time governor of the Habsburg Netherlands, had a number of manuscripts from Savoy brought to Mechelen , including “une grande heur escripte à la main” (a large handwritten book of hours). After her death in 1530, the book of hours came to Jean Ruffaut, who was in the service of her nephew Emperor Charles V and was appointed as one of her executors. After that, the trace of the manuscript is lost for more than two centuries.

In the 18th century it found itself in the possession of the Spinola , bound in red saffiano leather and provided with their coat of arms. How this Genoese family came about is unclear. However, various members of the family were involved in military operations in the Spanish Netherlands in the 17th century , notably Ambrosio . So it could have been spoils of war. Against this speaks again that they were on the side of the Habsburgs and could therefore poorly plunder Habsburg property. Later the Très Riches Heures came to the Margraves of Serra, who had their coat of arms affixed to the front cover above the Spinola coat of arms. What actually happened to the manuscript: inheritance, sale, donation is unknown. Only the owners (families) could be identified - not least thanks to the coat of arms. The Turin-based Baron Felix de Margherita inherited the manuscript from Marqués Jérôme Serra.

In 1855, Henri d'Orléans, duc d'Aumale , one of the most important art collectors of his time, heard about a medieval book of hours on sale in Italy. From the portrait of Jean de Berry on the January sheet, the bears and swans, the fleurs-de-lys, he could immediately see for whom the manuscript was originally made. However, the question remained open as to which of the numerous books of hours from Berry's estate it was. It was not until 1881 that Léopold Delisle could clearly assign it. Aumale kept the work under lock and key and only showed it to a select few guests. He bequeathed his extensive art collection to the Institut de France in 1897 on the condition that it must be kept closed. This obligation has been fulfilled to this day with the establishment of the Musée Condé in Aumales Castle Chantilly .

literature

- Raymond Cazelles , Johannes Rathofer: The book of hours of the Duc de Berry. Les Tres Riches Heures . VMA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 3-928127-31-4 .

- Franz Hattinger: Book of hours of the Duke of Berry , Hallwag AG, Bern 1960.

- Eberhard König: The Belles Heures des Duc de Berry. Great moments in book art . Theiss-Verlag Stuttgart, Facsimile-Verlag Luzern 2004, ISBN 3-8062-1910-9 .

- Eberhard König: Un grand miniaturiste inconnu du 15 e siècle français: Le peintre de l'Octobre des 'Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry'. In: Les dossiers de l'archéologie 16, 1976, pp. 92–123.

- Jean Longnon, Raymond Cazelles: Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Musée Condé, Chantilly 1969.

- Edmond Pognon: Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Ms. enlumine du XV e siècle. Ed. Seghers, Paris 1979. German: The Duke of Berry's Book of Hours. Painted manuscript of the 15th century. Parkland-Verlag, Stuttgart 1983 [various new editions], ISBN 3-88059-159-8 .

- Patricia Stirnemann: Combien de copistes et d'artistes ont contribué aux Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry? In: Elisabeth Taburet-Delahaye : La création artistique en France autour de 1400. École du Louvre, 2006 (Rencontres de l'école du Louvre 16), pp. 365-380, ISBN 2-904187-19-7 .

- Emmanuelle Toulet, Inès Villela-Petit, Patricia Stirnemann a. a .: Les Très Riches Heures. The masterpiece for the Duke of Berry . Quaternio Verlag Luzern 2013, ISBN 978-3-905924-21-3 .

- Jean-Baptiste Lebigue: Jean de Berry à l'heure de l'Union. Les Très Riches Heures et la réforme du calendrier à la fin du Grand Schisme. In: Christine Barralis [et al.]: Église et État, Église ou État? Les clercs et la genèse de l'État modern. École française de Rome / Publications de la Sorbonne, (Collection de l'École française de Rome 485/10), 2014, pp. 367-389, ISBN 978-2-85944-786-1 .

Movies

- Eye candy. The Duke of Berry's Book of Hours. (OT: De l'art et du cochon. Les très riches heures du Duc de Berry. ) Documentary, France, 2015, 25:50 min., Script: Xavier Cucuel, director: Chantal Allès, production: arte France, 2PL2, Productions Dix, series: Augenschmaus (OT: De l'art et du cochon ), first broadcast: February 12, 2017 by arte, summary by arte, ( Memento from February 19, 2017 in the Internet Archive )

- A year in the Middle Ages, painted in the Duke of Berry's book of hours. Documentary, Federal Republic of Germany, 1982, 43:30 min., Script and direction: Rainer and Rose-Marie Hagen, production: NDR , series: Zeitenwende , first broadcast: 1982 on Nord 3 , film data from KOBV .

Web links

- Roland Narboux: Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (French) - Introduction

- Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (engl.)

- Les Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry - The Calendar Pages (French / English) ( Memento from December 20, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

Individual evidence

- ↑ Luciano Bellosi: I Limbourg precursori di Van Eyck? Nuove osservazioni sui 'Mesi' di Chantilly. In: Prospettiva , 1, 1975, pp. 24-34.

- ↑ An identification of the painter with the master of Bartholomäus Angilicus in König 1976, which was appealing for various reasons and which the author later revised himself, see bibliography.

- ↑ The thesis on Barthélemy d'Eyck alias Cœur Meister or Master of King René as a painter of the 1440s as early as Bellosi 1975, for identification see Nicole Reynaud: Barthélemy d'Eyck avant 1450. In: Revue de l'art , 84, 1989, Pp. 22-43. See Catherine Reynolds: The “Très Riches Heures”, the Bedford workshop and Barthélemy d'Eyck. In: Burlington Magazine , 147, 2005, pp. 526-533 for a counter-argument.

- ↑ See Shane Adler: Article Months , in: Helene E. Roberts (ed.): Encyclopedia of comparative Iconography. Themes depicted in works of art. Chicago [u. a.] 1998, p. 626.

- ↑ Cf. Hagen, Rose-Marie and Rainer: Masterpieces in Detail - From the Bayeux Tapestry to Diego Rivera , Vol. 1, Cologne a. a .: Taschen 2005, p. 41.

- ^ Nicole Reynaud: Petite note à propos des Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry et de leur entrée à la cour de Savoie - Quand la peinture était dans les livres. Mélanges en l'honneur de François Avril. Turnhout 2007, pp. 273-277. According to her inventory from 1484, Charlotte de Savoie owned "ung autre live en parchement appellé les heures de Monseigneur de Berry, bien historié", which Avril identified with the Duke's Grandes Heures .