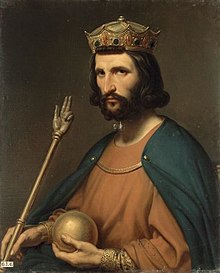

Hugo Capet

Hugh Capet ( French Hugues Capet * 940 or 941 , † 24 October 996 in Les Juifs at Chartres ) one was King of the Franks from 987 to 996. He was previously from 960 until his government beginning Duke of Franzien ( Dux Francorum) have been . He brought about a change of dynasty in western France ; the royal family of the Carolingians was replaced by a new dynasty, which was later named Capetian after Hugo's nickname . All later French kings and numerous other European ruling families and noble families were descendants of Hugo Capet in a direct male line. The Capetians' side branches included the Valois , the Bourbons, and the House of Orléans . The rule of the descendants of Hugo Capet, referred to as "House of France", was only finally ended by the February Revolution in 1848 .

origin

Hugo was born in 940 or 941 as the eldest son of Hugo the Great and his wife Hadwig (also Hedwig; † 959), a sister of Emperor Otto the Great . As Duke of Franzien and head of the Robertin family, Hugo the Great played an important role in West Frankish imperial politics; he was able to considerably expand the traditional position of power of his family by additionally acquiring the duchy of Burgundy and even a claim to Aquitaine recognized by the king . This made him more powerful than the king himself. The Robertiner family, whose head was Hugo Capet as his father's eldest son, had rivaled the Carolingian royal dynasty since the 9th century and had already established two kings, including Hugo Capet's grandfather Robert I. . , who had fallen in battle in 923 as an anti-king against a Carolingian. Therefore, the oldest living Robertine was always a potential candidate for royal dignity, but Hugo the Great shied away from reaching for the crown.

Position of power among the last Carolingians

Hugo the Great died in 956, but it was not until 960 that Hugo Capet received the Duchy of Francis, the most important of the numerous fiefs of the Robertines, from the Carolingian King Lothar, who was about the same age . This enabled him to assume the central role of his father as the most powerful vassal of the crown. He was the last Duke of France, because when he gained royal dignity in 987, the duchy was not reassigned, but abolished. The Duchy of Burgundy, which was also a fiefdom of Hugo the Great, transferred Lothar to Hugo Capet's younger brother Otto in 960 after Hugo and Lothar had carried out a joint campaign to subdue Burgundian insurgents in 958. Significant for the balance of power was the fact that after Otto's death in 965 the Burgundian greats, on the advice of Hugo Capet, elected the third and youngest son of Hugo the Great, Heinrich I the Great , who was also called Odo-Heinrich, as duke, without turning around to take care of the will of the king. Burgundy was therefore no longer considered a fiefdom of the crown, the Duke of Burgundy was only considered a vassal of the Duke of France. Lothar was deeply offended by this. The resulting tension between the King and the Duke of France required the Ottonians to mediate ; Emperor Otto the Great and his brother, Duke Brun of Lorraine, were maternal uncles of both Hugo Capet and the king. Even at the time of Hugo the Great, Otto the Great had tried to find a balance in conflicts between Carolingians and Robertinians and at the same time had opposed the traditional Carolingian claim to Lotharingia . He was not afraid of alternating sides and military intervention in western France. After Otto's death (973) the situation changed fundamentally. The previously good understanding between the Carolingians and the Ottonians broke up, and King Lothar took a hostile attitude towards the new ruler in the east, Otto II . This initially pushed the traditional contrast between Carolingians and Robertinians into the background, because Hugo Capet, in contrast to his father, proved to be a loyal vassal of his king in the external conflict.

The starting point of the East-West conflict was the dispute over the county of Hainaut in Lorraine , which was under the sovereignty of the East Franconian Empire. Duke Brun von Lothringen, Otto the Great's brother, had deposed the count there, whereupon his then underage sons Reginar IV and Lambert I had fled to western France. Immediately after the death of Otto the Great, they tried to regain their inheritance by force. For this project they found broad and energetic support at the court of Lothar and in the West Franconian nobility, including among the vassals of Hugo Capet. Although they failed militarily, Otto II gave them back most of their heritage in May 977. However, the conflict over the possession of Lotharingia remained unsolved. When Lothar launched a surprise attack on Aachen in 978 in order to capture Otto, who was there unsuspectingly, he could rely on Hugo's full support. Therefore, after the coup had just failed, Hugo's territories, like those of Lothar, became the target of Otto's massive counter-attack. Otto's invading army conquered Lothar's Palatinate and the city of Laon , but could not take the city of Paris, which was defended by Hugo , and had to withdraw. Since Hugo remained loyal to his king during this crisis, some historians count him among the representatives of a West Franconian or French sense of identity that emerged at the time, even if it was still weak.

After Lothar had made peace with Otto II in 980 without Hugo's participation, Hugo traveled to Rome at Easter 981, where Otto was staying at the time, in order to establish a good relationship with him. After Otto's death (983) Hugo no longer supported the Carolingian expansion policy to the east, but maintained a friendly relationship with the empresses Adelheid and Theophanu , who were responsible for Otto III. led the reign. He also intervened in favor of Archbishop Adalbero of Reims , against whom King Lothar wanted to initiate a high treason trial because of Adalbero's agreement with the Ottonians. When Hugo moved with six hundred men to Compiègne in May 985, where the trial was to take place on a court day, the meeting dissolved immediately.

In Aquitaine, Hugo Capet had already received the county of Poitou from the king in 960 , but could not stand against Duke Wilhelm III there. Enforce Werghaupt . It was not until he married Wilhelm's daughter Adelheid around 969 that he was reconciled with his son and successor Wilhelm IV. Eisenarm , with Hugo renouncing the claim to Aquitaine that his father had already made. Hugo also possessed or won other important allies by marriage. His sister Beatrix was married to Duke Friedrich I of Upper Lorraine; the other sister, Emma, married Richard I , the Duke of Normandy.

When Lothar died in 986 at the age of 44 after a short illness, his 19-year-old son Ludwig V was able to succeed him without any problems. As early as 979, with Hugo Capet's approval, Ludwig had been made co-king and thus designated heir to the throne. Hugo did not want to reach for the crown; like his father, he preferred to exercise a decisive influence on imperial politics under a relatively weak Carolingian.

Change of dynasty

Ludwig died 14 months after his accession to the throne on May 21, 987 in a hunting accident. Since he had left no son and his brothers were born out of wedlock and therefore unable to govern, only his uncle, Duke Karl of Lower Lorraine , could be considered as heir . Karl, the younger brother of King Lothar, who had already been completely ignored when Lothar came to power, now asserted his claim to the throne. But it failed because of the powerful aristocratic circles, including the Reims Archbishop Adalbero. Charles's opponents elected Hugo Capet to be king at a meeting in Senlis , with which they exercised their right to vote and denied a right of inheritance, but in fact created a new dynasty as a result. Probably on July 3, 987 Hugo was consecrated and crowned by Adalbero of Reims in Noyon .

The greats who elected Hugo as king were the same who had approved the takeover of Louis V in 979 and 986. The change of dynasty was not the result of a general dissatisfaction with the Carolingian ruling family, but a special constellation that worked against Charles. Karl had made powerful enemies. These included his sister-in-law, the queen widow Emma, whom he had accused of adultery, and the archbishop of Reims, who traditionally performed the royal coronation. Charles was also rejected at the Ottonian court. The Ottonians had given him the duchy of Lower Lorraine, but a union of this duchy with the West Franconian or French empire was not desirable from their point of view. Allegedly, when Karl was elected as a king, it was alleged that he had served a foreign ruler as Duke of Lower Lorraine and that he had entered into an inappropriate marriage.

government

Just six months after his own uprising, Hugo managed to get his son, the future Robert II , crowned co-king by Archbishop Adalbero of Reims at Christmas 987, thereby securing the succession to the throne. An election act did not take place. With this precedent, the hereditary kingship of the new dynasty prevailed against the suffrage to which Hugo Capet himself owed his rule. Initially, Archbishop Adalbero, who denied a right to inheritance to the crown in principle, resisted Hugo's request.

The base of Hugo's power was and remained in the north; as king he never stayed in the areas south of the Loire. In southern France, where loyalty to the Carolingian dynasty was more pronounced, he was initially denied recognition in some places. However, such a spirit of resistance showed itself only locally in the south and had no concrete impact.

While the crown vassals supported or accepted the change of dynasty, Duke Charles did not accept this development, but began the armed struggle for his claim to the throne. In 988 he succeeded in taking the royal city of Laon in one stroke . He was helped by his nephew Arnulf , an illegitimate son of King Lothar. In Laon, Charles was able to capture the queen widow Emma and the bishop Adalbero of Laon, a nephew of Adalberos of Reims. Prominent supporters of Charles were Count Heribert IV of Troyes and Odo I of Blois and the Archbishop of Sens (there was a traditional rivalry between the Archbishoprics of Sens and Reims). Otherwise, however, Karl's company found little approval among the nobility. Repeated attempts by King Hugo and his son Robert to retake Laon by siege were unsuccessful.

When Archbishop Adalbero of Reims died in early 989, Hugo decided to have Karl's nephew Arnulf elected as Adalbero's successor in order to pull him over to his side. However, this plan failed completely; In August 989, Arnulf gave Reims to his uncle Karl, with which he broke Hugo's oaths. By taking the coronation city of Reims, Charles's position was greatly strengthened, but he failed to substantiate his claim to the throne with an election and coronation in Reims. After three years of struggle, Karl fell through treason. Bishop Adalbero of Laon, who had in the meantime gained Charles's trust, opened the city gates of Laon to the troops of the Capetian at the end of March 991. Karl was arrested with his wife and children. He remained in custody until the end of his life. Adalbero's betrayal attracted a great deal of attention and remained a popular topic in historiography and popular literature for centuries; it has been compared to Judas Iscariot's betrayal of Christ.

King Hugo now sought the impeachment of Archbishop Arnulf von Reims, who had betrayed him. However, he was unable to assert himself in a long-standing dispute about it, the great "Reims Church dispute", and got into a conflict with Pope John XV. who claimed sole competence for such a step. First Hugo forced Arnulf von Reims to resign at the Imperial Synod of Saint-Basle (Verzy) convened by him in June 991. At this synod, Bishop Arnulf von Orléans, a zealous follower of Hugo, directed extremely sharp attacks against the papacy. He called the popes monsters and even equated a bad pope with the antichrist . This gave the conflict a scope that went far beyond the specific case. The opposing party, whose spokesman was the influential Abbot Abbo of Fleury , offered bitter resistance, with the support of the German bishops. The dispute dragged on until after Hugo's death. Because of its fundamental importance, the Reims church dispute is sometimes viewed as a forerunner of the later disputes between popes and French kings over Gallicanism .

Hugo Capet, like his father, was buried in the Saint-Denis basilica .

nickname

The epithet Capet is not documented at the time, but only appears in the sources in the 11th century. Originally he was referring to Hugo's father, Hugo the Great; referring to Hugo Capet, it was not used until the 12th century. It is derived from the Latin word cappa , which means a coat. According to the common interpretation, it was the coat that abbots wore. This alluded to the fact that Hugo the Great or Hugo Capet was lay abbot of several monasteries. Traditionally Robertine abbeys, whose lay abbots were held by Hugo the Great and Hugo Capet, were Saint-Martin de Tours , Saint-Denis , Saint-Germain-des-Prés , Saint-Maur-des-Fossés , Saint-Riquier and Saint-Aignan in Orléans . A different interpretation of the epithet says that the cappa was the cloak relic of St. Martin of Tours and that alludes to the role of the Duke of Franz as lay abbot of Saint-Martin de Tours.

family

Around 969 Hugo Adelheid married of Aquitaine , a daughter of Duke Wilhelm III. Tow head of Aquitaine and the Gerloc- Adele of Normandy. She is also known as Adelheid von Poitou. With her he had a son, heir to the throne, and three daughters:

- Hedwig ( Hedwige ), * probably 969; † after 1013; ∞ around 996 Reginar IV. ( Rainier IV. ), Count of Hainaut ; † 1013 ( Reginare )

- Gisela ( Gisèle ), * probably 970, heiress of Abbeville ; ∞ before 987 Hugo I of Montreuil ( Hugues I de Montreuil ), Count of Ponthieu ; † around 1000

- Robert II the Pious ( le Pieux ), born March 27, 972 in Orléans ; † July 20, 1031 in Melun , from 988 king and co-regent, from 996 king of France

- Adelheid ( Adélaide, Aelis ), * probably 973

Furthermore Hugo had an illegitimate son Gauzlin from an unknown woman ; † November 19, 1030 probably in Bourges , who became abbot of Fleury in 1005 and archbishop of Bourges in 1013 .

According to a legend, Saint Aurelia von Regensburg was also a daughter of Hugo.

|

Robert the Strong (X866) 853 Count of Tours, 861 Count of Paris |

|||||||||||||

|

Robert I (866–923) 922 King of France |

|||||||||||||

| Adelheid of Tours († after 866) | |||||||||||||

|

Hugo the Great (probably 895–956) 936 dux Francorum |

|||||||||||||

|

Heribert I. (probably 850–900 / 906) 896 Count of Vermandois |

|||||||||||||

| Beatrix of Vermandois († after 931) | |||||||||||||

| NN ( Bertha von Morvois ) | |||||||||||||

| Hugo Capet (941–996) 987 King of France |

|||||||||||||

| Otto the Illustrious († 912) | |||||||||||||

|

Heinrich I (around 876–936) 919 King of Eastern France |

|||||||||||||

| Hadwig († 903) | |||||||||||||

| Hadwig of Saxony (914 / 920–959) | |||||||||||||

| Dietrich († after 929) Count in Saxony |

|||||||||||||

| Mathilde the saint (around 895–968) | |||||||||||||

| Reginlind of Denmark († after 929) | |||||||||||||

reception

From the perspective of posterity, the role of Hugo as the founder of the dynasty and the dispute about the legitimacy of his rule were in the foreground in the Middle Ages. In modern times, and especially in modern research, the question of his personal role in French history has increasingly been asked.

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the legality of the dynasty change of 987 was controversial among French historians; there was no shortage of voices calling Hugo a usurper (especially in the 11th and 12th centuries), although his descendants ruled at that time.

In the 13th century (probably first in anti-French circles in Italy) a legend hostile to the Capets emerged that attributed Hugo to a bourgeois origin; he was the son of a Parisian butcher. Dante processed this motif in his Divine Comedy . He put Hugo Capet (whose figure he mixed with that of Hugo the Great) into purgatory and put a long speech in his mouth. In it, Hugo described himself as "the root of the bad tree" that had overshadowed Christianity.

Hugo Capet is the hero of a chanson de geste written around 1360 , in which the tradition of an originally bourgeois origin of the dynasty is taken up, but strongly toned down and turned into the positive. Now Hugo's father is not a butcher, only his maternal grandfather, and the richest butcher in the country. Through his great deeds, Hugo achieved the crown of France as an excellent knight by winning the favor of the heiress to the throne Marie, who married him to the delight of the Parisians, although the great vassals disliked his pedigree of a butcher. The work reflects the political crisis at the time of its creation, in which the Parisian bourgeoisie under Étienne Marcel briefly became a decisive factor in French politics. Around 1437 Elisabeth von Lothringen made a German prose translation of the epic with the title Hug Schapler .

In his last surviving poem to the prison officer Garnier (1463), the French poet François Villon also alludes to Hugo Capet's alleged origins in the butcher's shop.

Modern times

In the early modern period and still in the 19th century, a view became noticeable that made Hugo the representative of a "national" concept of France that opposed "the Germans". In a milder form, this interpretation was that the Robertines or Capetians embodied the nascent French nation, the Carolingians the concept of the declining Franconian universal state. The then leading French medievalist Ferdinand Lot , who denied any ideal difference between Carolingians and Capetians, turned against this in the late 19th century . This view has prevailed.

In modern research, Hugo Capet is usually judged relatively unfavorably by German and French historians, referring to the limited scope of his achievements and his lack of energy. Walther Kienast writes of the “impetuous, deliberate nature of this very mediocre man, averse to all big undertakings”, Karl Uhlirz believes he can recognize a “dry, caring for the next” way and a “lack of any higher common sense”. The often cited verdict of the Frenchman Ferdinand Lot was even sharper. He came to the conclusion that Hugo owed the throne neither to his courage, his skill, nor any enthusiasm of others for a change. Hugo had no ideas or principles of his own and did not even strive for kingship; it fell into his lap through a combination of coincidences. “There is evidence that his courage was extremely modest. His skill has been praised by certain scholars. But we are still looking for it; all we have seen is a weak, insecure man who does not dare to take a step without asking for advice, and whose caution has become faint-hearted. "

The anniversary year 1987 of Hugo Capet's accession to the throne provided the occasion for numerous publications and honors.

Sources (editions and translations)

- Hugo Capet's documents are not yet critically edited. The old edition by Jean-Baptiste Haudiquier and others is used. a. in the Recueil des Historiens des Gaules et de la France Vol. 10, 2nd edition (obtained from Léopold Delisle ), Paris 1874, pp. 543-564.

- Edmond Pognon : Hugues Capet, roi de France , Paris 1966 [contains French translations of important Latin source texts, including documents and letters]

- Noëlle Laborderie (Ed.): Hugues Capet. Chanson de geste du XIVe siècle , Champion, Paris 1997. ISBN 2-85203-627-4

literature

- Hans-Werner Goetz : Hugo Capet. In: Lexicon of the Middle Ages . Volume 5. 1989, Col. 157f.

- Elizabeth Hallam: Capetian France. 987-1328 . Longman, London et al. a. 1980, ISBN 0-582-48909-1 .

- Ferdinand Lot : Etudes sur le règne de Hugues Capet et la fin du Xe siècle . E. Bouillon, Paris 1903 ( Bibliothèque de l'École des Hautes Études - Sciences philologiques et historiques 147, ISSN 0761-148X ), (basic standard work).

- Michel Parisse , Xavier Barral i Altet (ed.): Le roi de France et son royaume autour de l'an mil . Actes du Colloque Hugues Capet 987-1987, La France de l'an Mil, Paris-Senlis, 22-25 June 1987. Picard, Paris 1992, ISBN 2-7084-0420-2 .

- Yves Sassier: Hugues Capet. Naissance d'une dynasty . Fayard, Paris 1987, ISBN 2-213-01919-3 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Hugo Capet in the SUDOC catalog (Association of French University Libraries)

Individual evidence

- ↑ On Hugo's enfeoffment, see Walther Kienast: The Duke Title in France and Germany (9th to 12th Century) , Munich 1968, pp. 68–76.

- ↑ Kienast (1968) pp. 68, 76, 81.

- ↑ Kienast (1968) pp. 81f., 95.

- ↑ Walther Kienast: Germany and France in the Imperial Era (900-1270) , 1st part, Stuttgart 1974, p. 86.

- ↑ Kienast (1974) pp. 87f.

- ↑ Kienast (1974) pp. 89f.

- ↑ On the course of the siege see Kienast (1974) p. 94f.

- ↑ On the question of the beginnings of a West Franconian or French “state idea” in the 10th century, see Kienast (1974) pp. 94f.

- ↑ Kienast (1968) pp. 81-83.

- ↑ On the dating of Karl Ferdinand Werner : Vom Frankenreich zur Entfaltung Deutschlands und Frankreichs , Sigmaringen 1984, p. 249, note 11; Joachim Ehlers : Die Kapetinger , Stuttgart 2000, p. 30f .; Carlrichard Brühl : The birth of two peoples , Cologne 2001, p. 188f. Kienast (1974) p. 118 and note 273, who advocated June 1st, was of a different opinion.

- ^ Rudolf Schieffer : Die Karolinger , Stuttgart 1992, p. 220f.

- ↑ Kienast (1974) p. 118. Ehlers p. 30 emphasizes that these reasons were not the decisive ones; see. Ferdinand Lot: Les derniers Carolingiens , Neudruck Genève 1975, p. 294 and note 1. Brühl p. 188 considers the whole argumentation to be fictitious.

- ↑ Kienast (1968) p. 14 and note 18; he quotes from a private document from 991, where instead of the usual indication of the year of rulership, it says "under the government of our Lord Jesus Christ, while with the Franks Hugo illegally claimed rule".

- ↑ For details see Lot (1975) p. 292 and note 1.

- ↑ Ehlers pp. 33-35.

- ↑ Kienast (1974) pp. 125-127.

- ↑ The use and meaning of the epithet was examined by Lot (1903) pp. 304–323.

- ↑ Lot (1975) p. 184; see also Lot (1903) pp. 226, 230f.

- ↑ Ehlers p. 28f.

- ^ Dante: Divina commedia , Purgatorio 20, 16-123.

- ^ François Villon: Complete Works. Bilingual edition , ed. u. trans. by Carl Fischer. Munich 2nd edition 2002, p. 238: " Se fusse des hoirs de Hue Capel / Qui fut extrait de boucherie [...]" ("If I were among Hugo Capet's heirs, emerged from the butcher's shop (...)"; in Carl Fischer's metric adaptation: "If I were a Capetian, a butcher's son with royal consecrations (...)")

- ↑ Pognon pp. 228-230; Lot (1975) pp. 382-394.

- ↑ Kienast (1974) p. 95.

- ^ Karl Uhlirz: Yearbooks of the German Empire under Otto II. And Otto III. , Vol. 1: Otto II. 973-983 , Berlin 1967, p. 114, note 30.

- ↑ Lot (1975) p. 295.

| predecessor | Office | successor |

|---|---|---|

| Ludwig V. |

King of France 987–996 |

Robert II |

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hugo Capet |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | King of France (987-996) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 940 or 941 |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 24, 996 |

| Place of death | Les Juifs near Chartres |