Anal atresia

| Classification according to ICD-10 | |

|---|---|

| Q42.2 | Anal atresia with fistula |

| Q42.3 | Anal atresia without a fistula |

| ICD-10 online (WHO version 2019) | |

The anal atresia , common anorectal malformation is a congenital malformation of the rectum . The anus for excreting the intestinal contents is missing . The Rektalatresie also referred to the lack of the lower part of the rectum.

Anal atresia occurs when the anal pit does not break through into the rectum, which usually occurs in embryos 3.5 cm in length. The malformation manifests itself in every 3,000th to 5,000th newborns, in other words, in 0.2–0.33 ‰. That is between 130 and 250 children a year in Germany. Usually the malformation is diagnosed after birth . It must be treated surgically. The anal or rectum atresia is often associated with other malformations.

history

The oldest traditions of descriptions and treatments of the malformation come from antiquity. The Greek doctor Paulos of Aegina treated the malformation by opening the perineum (the dam), probably at the anal pit. The intestinal contents could get out through the opening. Those who survived this procedure suffered from the deep form of the malformation, i.e. only from anal atresia, in which the missing section of the intestine is very short. Children with the tall form (rectal atresia) could not be treated successfully in this way.

The surgeon Jean Zuléma Amussat (1796–1856) developed a forerunner of the pull-through operation that is still used today. His anorectoplasty was used in the high form (rectal atresia) until the 1960s. Otherwise, the doctors resorted to the operation on the perineum. Many patients remained incontinent . A major innovation was Alberto Peña's suggestion of posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. According to a study published in 2002, the number of good results is 32–100% in the Peña operation compared to 5–68% in the pull-through operation. Laparoscopic surgery is used today for very tall forms .

frequency

The numbers on the occurrence of the malformation vary greatly. In various studies, two to five diseases per 10,000 births were found. In the basic report of the “Berlin Health Report”, 0.25 cases per 1000 live births are given for 1999 . Levitt and Peña state one disease per 5000 live births.

Male newborns show the malformations more often than female ones. There is no clarity about the influence of ethnic factors. The result of a study from 1995 is that the malformation occurs more frequently in people with dark skin color ( prevalence ). This result could not be confirmed in other studies.

diagnosis

Anal atresia is noticeable when a newborn child has no anus, a fever cannot be taken, or stool leaks in an atypical location (such as the vagina ). In girls, the examination of three openings in the genital area ( urethra , vagina and anus ) is of great importance for therapy.

Anal atresia can only be diagnosed during pregnancy due to accompanying malformations. It is hardly recognized even with fine ultrasound or in the third trimester of pregnancy. A sonography in the third trimester should make it possible to detect enlarged sections of the intestine or a blind sac; however, they were regularly not recognized in practical observation. However, prior identification is possible if other malformations (skeleton, heart, esophagus, etc.) are also present. However, perineal fistulas in particular simulate a normal anus and are not recognized for several months or years. For this perineal form, there is evidence of a familial accumulation (1% also in relatives); the other forms usually occur spontaneously.

After the first assessment, a perinaeal sonography is performed to determine the distance between the rectum blind sac and the target anus and to exclude further malformations, e.g. B. the kidneys and the spinal canal. A fistula can usually not be shown sonographically.

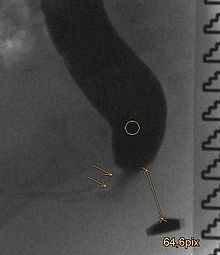

In the absence of an externally recognizable fistula in front of the birth and insufficient visualization, a radiological examination is carried out natively as a side view of the pelvis with a horizontal beam path in the prone position with an elevated pelvis, only 16 to 24 hours after the birth so that the blind sac is sufficiently air-filled. In the case of a probable fistula, the examination is carried out as fluoroscopy with a contrast medium . A magnetic resonance imaging and other measures can also be used as part of the diagnosis.

Because of the accompanying malformations, other diagnostic procedures are often used. A micturition cystourethrogram can be carried out to exclude or detect vesicouretherelaen reflux .

classification

There are various classifications of this malformation. Santulli suggested differentiating between deep, intermediate and high malformations. This classification is still partly used today. However, it does not address the wide variety of defects. Therefore, the Wingspread and Peña classifications are used today.

| male | Female |

|---|---|

|

|

| male | Female |

|---|---|

|

|

Occurrence

The following hereditary diseases are associated with anal atresia:

- Baller-Gerold syndrome

- Duane-Radial Ray Syndrome

- Embryofetopathia diabetica

- FG syndrome

- Johanson Blizzard Syndrome

- Cat's Eye Syndrome

- Caudal regression syndrome

- Short rib polydactyly syndromes

- McKusick-Kaufman syndrome

- Okihiro syndrome

- Sirenomelia

- Townes-Brocks Syndrome

- VACTERL association

Accompanying malformations

About half of the children concerned have other malformations. The accompanying malformations are more frequent and more severe in the high form than in the deep form. The number of cases of concomitant malformations is listed below. The numbers depend on the classification of the malformation and vary in different studies:

- Malformations of the urogenital tract: 30–50%

- Malformations of the gastrointestinal tract: 4–8%

- Vertebral malformations: 15–54%

- Heart defects : 9-11%

- Malformations of the extremities: 18%

- Esophageal atresia : 10%

- other malformations: 20%

pathology

The causes of the malformation have not yet been clarified. Researchers suspect that the causes depend on many factors and that genetic factors play a major role: the risk that siblings of a child with anal atresia also have this malformation is around 1: 100, for the mildest forms, while the probability is otherwise 1: 3000 to 1: 5000. Cuschieri examined over 1,800 patients. Around two thirds had other anomalies in addition to anorectal malformations and 15% had genetic defects . Mainly the Down , Edwards and Pätau syndromes were found . Another group of 15% had a VACTERL association .

therapy

Depending on the extent of the malformation, an enterostomy (artificial anus) is first created or an operative correction of the malformation is carried out. In the former case, the main operation takes place between three and nine months of age. The complete malformation must always be corrected. The most common type of operation is the posterior-sagittal procedure (posterior sagittal anorectoplasty) according to Peña-deVries, s. u. After an appropriate waiting period, the enterostoma is moved back in a final step. The operation can also be performed gently laparoscopically .

The first two days of life are crucial for further therapy. During this time, any accompanying malformations must be diagnosed. In particular, it must be found out whether these endanger the life of the newborn and should be treated immediately. Furthermore, the decision about the creation of an anus praeter or an immediate operation is made here. For this selection, it is important to observe all changes in the first 24 hours of life, as well as the physical condition of the newborn and the presence / absence of a perineum.

Three surgical methods are used to correct the malformation:

- Abdominoperineal pull-through operation

- Abdomino-sacroperineal pull-through operation according to Stephens

- posterior sagittal anorectoplastic surgery

Abdominoperineal pull-through surgery was the standard procedure for treating anal atresia until the mid-20th century. During the operation , the patient lies in the lithotomy position , the rectum is guided to the perineum with a sling and sutured there.

In the abdomino-sacroperineal pull-through operation according to Stephens, the treatment is carried out in the prone position . The incision begins at the sacrum and ends in the perineum. After the opening, the part of the intestine that ends blind is detached, any fistula that may be present (to the vagina, to the bladder or to the outside) is closed and the piece of intestine is pulled through the levator ani muscle . The piece is then sewn onto the skin. Until the mid-1980s, this was the most common treatment for anal atresia.

Peña and deVries refined the above methods and described the procedure as posterior sagittal anorectoplasty. It is currently the standard procedure for treating the malformation. The operation is performed in the prone position. The sphincter is subjected to electrical stimulation in order to determine the force required to contract it. This determination can be used as an indicator of the patient's subsequent continence. In contrast to the above procedure, the incision is made exactly in the center line. Peña-deVries were able to demonstrate a more favorable prognosis for stool continence. The surgeon then separates the rectum from the genitourinary tract until there is sufficient length to anastomize it to the perineum. After the operation, the diameter of the anus is initially smaller than would be normal for the elderly and must be widened. The tissue can be stretched to the required size with hegar pens of different sizes. This maintains the muscular tension to ensure continence.

After the required widening of the anal canal has been achieved, the enterostoma is closed. This usually happens three to four months after the operation.

After surgical therapy, follow-up care by the parents has a significant influence on the continence result. Therapy options include physiotherapy (pelvic floor training), nutritional advice, medication, stool training, systematic colon irrigation, etc.

Aftercare

Faecal incontinence (involuntary stool) and / or constipation (constipation) occur later in many children. Recognizing and treating problems of the urinary tract that often occur at the same time are of great importance for life expectancy. Continuous follow-up care in an appropriate center is therefore of great importance for the quality of life and life expectancy of the children. Part of the aftercare should be to achieve social continence using multimodal therapy options. As with all potentially chronic malformations, the information on social and psychological support options should be observed in order to avoid or reduce chronification.

forecast

Anal atresia can now be treated surgically if the diagnosis and the correct procedure are correct. The long-term prognosis correlates with the severity of the accompanying coccyx and sacrum agenesis. With regular and comprehensive follow-up care, social continence can almost always be achieved. Often in adolescence it is much easier to manage social continence. Experience on possible pregnancies after cloacal malformation is still scarce.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ W. Stoeckel: Textbook of Gynecology. 11th edition Hirzel, Stuttgart 1947.

- ↑ a b c Guideline of the German Society for Pediatric Surgery on Anorectal Malformations AWMF Guideline, Reg. No. 006-002, as of 2013, accessed on November 7, 2018

- ^ A b Marc A. Levitt, Alberto Peña. Anorectal malformations (PDF; 1.2 MB). Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 2007.

- ↑ AM Holschneider, NK Jesch, E. Stragholz, W. Pfrommer: Surgical Methods for Anorectal Malformations from Rehbein to Peña - Critical Assessment of Score Systems and Proposal for a New Classification . In: European Journal of Pediatric Surgery . tape 12 , no. 2 , 2002, p. 73-82 , doi : 10.1055 / s-2002-30166 .

- ↑ Roman M Sydorak, Craig T Albanese: Laparoscopic repair of high imperforate anus . In: Seminars in Pediatric Surgery . tape 11 , no. 4 , November 2002, p. 217-225 .

- ↑ a b c d Alexandra Werner. Anorectal malformations , dissertation at the Medical Faculty of the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich . 2006 (PDF file)

- ^ Harris et al .: Descriptive epidemiology of alimentary tract atresia . Teratology . Volume 52 Issue 1, Pages 15–29. 1995

- ↑ Anorectal malformations ( memento of the original from January 19, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 3.6 MB). Pediatric surgical training at the University of Nijmegen

- ^ V. Hofmann, KH Deeg, PF Hoyer: Ultrasound diagnostics in paediatrics and pediatric surgery. Textbook and atlas. Thieme 2005, ISBN 3-13-100953-5

- ↑ W. Schuster, D. Färber (editor): Children's radiology. Imaging diagnostics. Springer 1996, ISBN 3-540-60224-0

- ^ William E. Ladd, Robert E. Gross: Congenital malformations of anus and rectum: Report of 162 cases . In: The American Journal of Surgery . tape 23 , no. 1 , January 1934, p. 167-183 , doi : 10.1016 / S0002-9610 (34) 90892-8 , PMID 5423060 .

- ↑ Alfred Cuschieri: Anorectal anomalies associated with or as part of other anomalies . In: American Journal of Medical Genetics . tape 110 , no. 2 , June 15, 2002, p. 122-130 , doi : 10.1002 / ajmg.10371 .

- ↑ H. Koga, T. Ochi, M. Okawada, T. Doi, GJ Lane, A. Yamataka: Comparison of outcomes between laparoscopy-assisted and posterior sagittal anorectoplasties for male imperforate anus with recto-bulbar fistula. In: Journal of pediatric surgery. Vol. 49, No. 12, December 2014, pp. 1815-1817, ISSN 1531-5037 . doi: 10.1016 / j.jpedsurg.2014.09.028 . PMID 25487490 .

- ↑ Guochang Liu, Jiyan Yuan, Jinmei Geng, Chunhua Wang, Tuanguang Li: The treatment of high and intermediate anorectal malformations: One stage or three procedures? In: Journal of Pediatric Surgery . tape 39 , no. 10 , October 2004, p. 1466-1471 , doi : 10.1016 / j.jpedsurg.2004.06.021 .

- ^ Pieter A. deVries, Alberto Peña: Posterior sagittal anorectoplasty . In: Journal of Pediatric Surgery . tape 17 , no. 5 , October 1982, p. 638-643 , doi : 10.1016 / S0022-3468 (82) 80126-7 , PMID 7175658 .