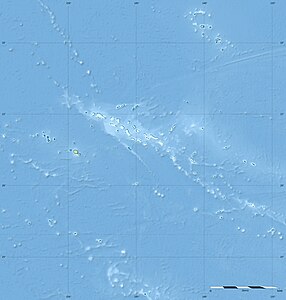

Rapa Iti

| Rapa Iti | ||

|---|---|---|

| NASA image of Rapa Iti | ||

| Waters | Pacific Ocean | |

| Archipelago | Austral islands | |

| Geographical location | 27 ° 36 ′ 20 ″ S , 144 ° 20 ′ 40 ″ W | |

|

|

||

| surface | 38 km² | |

| Highest elevation | Mont Perau 633 m |

|

| Residents | 515 (2017) 14 inhabitants / km² |

|

| main place | Ahurei (Haurei) | |

| Ahurei Bay with the main town of the same name | ||

Rapa Iti (short name: Rapa , old name: Oparo ) is a 38 km² inhabited island, which geographically belongs to the Austral Islands and politically to French Polynesia .

geography

Rapa Iti translates as Little Rapa, in contrast to Rapa Nui (German: Big Rapa), the official name of Easter Island . Rapa Iti is located in the southeastern Pacific Ocean and geographically belongs to the Austral Archipelago , more precisely to the subgroup of the Bass Islands. The closest inhabited island is Raivavae , 537 km to the northwest.

With around 38 km² of land, Rapa Iti is relatively small and has several offshore side islands , the largest of which are Karapoo and Tauturoo on the south coast. The landscape profile is mountainous with jagged peaks and the 633 m high Mont Perau as the highest point.

The "Pacific Islands Pilot", the sea handbook of the Pacific Islands, gives a clear description of the landscape:

“Where the steep edges of the rugged peaks reach the coast, they form large cliffs that fall perpendicular to the sea. The coast is rugged with deep surf caves. Except for the bays, the island is inaccessible. "

George Vancouver , who aptly described Rapa as rugged and made up of steep mountains with very little level ground , had the same dismissive impression . The steep coast rises directly from the sea and is exposed to a violent surf because there is no offshore coral reef. The island has no coastal plain and no sandy beaches. Only the narrow valleys between the steep mountain slopes offer space for limited cultivation. The coastline is often divided up by bays, these are the only places where access to the interior of the island is possible. The largest is Ahurei (or Ha'urei) Bay, the remnant of a sunken caldera . The two settlements, Ahurei and the smaller area, are opposite each other at the ends of this bay. All the residents of Rapa Iti, mostly Polynesians and a few Europeans, live in these two villages.

climate

Rapa Iti is in the tropical zone, Af according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. In Ahurei the average annual temperature is 20.9 ° C. The warmest month (in the southern summer) is February, the average temperature is 24.1 ° C, the coolest month is July with an average of 18.3 ° C. Frost days do not occur.

The sky is often overcast. Within a year, an average of 2653 mm of precipitation falls (compared to Cologne with 774 mm), although the months differ significantly. In October, the driest month, the average fall is 171 mm, whereas in March, with its heavy rainfall, it is 266 mm.

vegetation

The original flora of Rapa Iti has already been damaged by the native Polynesian people and even more so by the free-range goats that the Europeans introduced. Remnants of the native mountain rainforest can still be found in the high elevations and in the crevices and steep slopes that are inaccessible to goats.

The native vegetation has a higher biodiversity than other tropical islands of comparable size and shows some similarity to that of New Zealand, which is much further west . However, there are numerous endemics, for example of the genera Fitchia, Bidens , Oparanthus and Sclerotheca .

The ridges and crevices of Mt. Perahu, which appears bare from a distance, receive most of the moisture and are covered by low-growing, bushy vegetation consisting mainly of Metrosideros , which do not grow taller than a meter, Weinmannia , Bidens and Freycinetia . There are also dwarf shrubs of the genus Plantago and numerous, sometimes endemic, ferns, for example Blechnum venosum and Blechnum pacificum , which was first described in 2011.

The middle layers are dominated by Metrosideros collina and the endemic Myoporum rapense and Freycinetia rapensis .

In lower elevations, the crops dominate, for example the intensely cultivated taro in the damp side valleys. For a while, people also planted coffee, but this has become much less important due to the drop in coffee prices. However, large parts of the mountain slopes have been cleared, eroded and covered with secondary vegetation, which consists mainly of robust grasses.

geology

The Austral Islands form a chain in the South Pacific that is more than 1500 kilometers long and extends from east-southeast to west-northwest to the Îles Maria . They are the product of a hotspot under the still active Macdonald Seamount , which is now only 27 meters below sea level at the southeast end of the Austral Islands. The geologically oldest, more eroded and rugged islands are in the northwest, the younger ones in the southeast of the chain. Rapa Iti is the penultimate island of the group, further to the east-southeast only the uninhabited rocky islets of Marotiri and finally the Macdonald-Seamount follow . The chain of islands runs almost parallel to the direction of movement of the Pacific plate , which has been crawling here for 43 million years (Middle Eocene , Lutetian ) in a west-northwest direction (N 300) at an average speed of 110 millimeters / year. The oceanic crust at the Macdonald-Seamount is 35 million years old (Upper Eocene, Priabonian ), is getting older towards the northwest and is already 80 million years old at the northwest end of the island chain (Upper Cretaceous, Campanium ).

Rapa Iti sits bathymetrically on a 150-kilometer-long and 50-kilometer-wide submarine high plateau, which is around 1000 meters below sea level and its longitudinal axis runs in a southeast-northwest direction. This plateau in turn forms part of an even larger, 200-kilometer-wide high structure, which, starting from the Macdonald-Seamount, reaches up to 200 kilometers south of Raivavae , recognizable by the 2000 meter depth line. To the southwest, the high plateau slopes down to the 4000 to 5000 meter deep Abyssal of the South Pacific.

A huge canalized mass movement has taken place southwest of the island , which occupies almost the entire width of the island and is likely to be related to the collapse of the caldera . The demolition took place in about 1000 meters water depth, is 14 kilometers southwest of the coast in 3000 meters water depth and then runs out in the Abyssal.

The island is of volcanic origin and was formed about 5.1 million years ago. The rocks are typical oceanic island basalts (OIB) with weakly pronounced DUPAL anomalies - mainly alkali basalts and basanites with 44 to 45 percent by weight SiO 2 content. Geochemically, they are comparable to the neighboring volcanic rocks of Marotiri and Macdonald-Seamount, but there are also similarities in the isotope ratios to the volcanic rocks of Atiu and Rarotonga ( Cook Islands ), to the volcanic rocks of the Marquesas Islands and even to the Ko'olau shield volcano Oahus .

history

prehistory

The island of Rapa has recently been the target of extensive archaeological research, which continues to this day. It is an impressive example of the development of fortified mountain villages in Polynesia with advanced, well-designed defenses. Science has mainly focused on this period of the island's history, so little is known about the early history. It is unclear when and from where the Polynesians first colonized the island. Radiocarbon dates go back to around 1200 AD. Because of its peripheral location in the Polynesian Triangle, it can be assumed that the Austral archipelago was populated relatively late, most likely in the early 2nd millennium AD, starting from the Society Islands , possibly also from Mangareva or the Cook Islands, the small and isolated Rapa probably later than the other Austral Islands.

The archaeologist John FG Stokes (1875-1960) from the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu has identified coastal caves or rock overhangs in some bays as original forms of settlement. Later coastal settlements can be proven by the remains of house terraces, earth ovens and other structures. Several tribal principalities with a strictly stratified social structure established themselves very quickly. The Ariki - a kind of hereditary nobility - were at the top of the social pyramid. The socio-history is determined by frequent, ritualized tribal wars, but it seems that shortly before the European discovery, a clan was able to assert itself as the central power.

Already George Vancouver , the first European explorers, fell by just looking through the telescope six fortresses on the steep ridges around the Ahurei Bay on. But it was not until the middle of the 19th century that the New Zealand captain John Vine Hall examined and described the mountain fortresses of Rapa, albeit very superficially and without expertise.

The term “fortresses” for the extensive structures is actually too short-sighted, because they are strongly fortified fortified villages with a well thought-out defense system made of stone-clad earthworks , trenches and palisades . The complex also includes terraces for residential development with houses made from perishable materials as well as irrigated cultivation terraces. Large fortifications are often associated with smaller ones, probably satellites of larger settlements or temporary refuges. The size of the systems varies, they covered areas from a total of 3040 m² to 25,237 m². The mountain peaks and the steep ridges were extensively redesigned for this.

As an example, the fortress of Morongu Uta, excavated by the American anthropologists William Mulloy and Edwin N. Ferdon in 1956, is mentioned, which is located on a 380 m high mountain above Ahurei Bay. The islanders dug the mountain top so that it resembles a tetrahedron with a flattened top . The sides of the triangular tower created in this way were secured with walls made of unworked basalt stones. As the islanders told Thor Heyerdahl , the tower was the chief's residence. Several terraces extended beneath this , which were used for residential purposes, as one can infer from the numerous earth ovens and storage pits, as well as finds of basalt dexels and stone taro pestles. The entire complex is surrounded by an extensive circular moat that can still be seen today, which was at least partially surrounded by wooden palisades, as archaeologically verifiable post holes prove. Below the residential quarters, like huge steps, lay numerous artificially irrigated terraces of various sizes that were used for growing taro. The evaluation of the charcoal samples collected in the earth ovens with the radiocarbon method showed that Morongo Uta was inhabited between 1450 and 1550 AD.

The anthropologist Sir Peter Henry Buck ( Te Rangi Hīroa ) compared the mountain fortresses Rapa Itis with the Pā , the fortified villages of New Zealand 4000 km away . Fortified hilltop settlements are not uncommon in Polynesia. There are comparable defensive villages not only in New Zealand, but also in Samoa and the Marquesas , but also in Micronesia , for example on Babeldaob . They probably served as defenses and refuge in the numerous tribal wars.

The main food of the indigenous peoples - and part of every meal to this day - was popoi , a musty and sour-tasting dough made from crushed taro that was fermented in earth pits and thus preserved for a long time. There is a similar process, with the breadfruit , in the Marquesas. Seafood (crustaceans, mussels and fish caught in fish traps ) as well as pigs and chickens were supplemented and enriched in the meals .

European discovery

The first European to discover Rapa Iti was George Vancouver. He named the island Oparo and was apparently not enthusiastic about his discovery:

“No semblance of abundance, fertility, or cultivated land. [The island was] mostly covered with shrubs and dwarf trees. "

The HMS Discovery and the HMS Chatham anchored on December 22, 1791 in Ahurei Bay. Numerous canoes approached; several were double-hulled canoes with a crew of 25 to 30 men, including some warriors armed with spears, slingshots and clubs. Vancouver did not enter the island. Despite his fears about the armament and the threatening fortifications, the encounter remained peaceful.

At dawn on June 29, 1820, the ships Vostok and Mirny of the Imperial Russian Navy under the command of Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Michail Petrovich Lasarew reached the island of Rapa. The officers and men did not go ashore, however. When 22 canoes with around 100 people approached, there was a brisk trade on board the ships. In exchange for an ax (for the chief) and all sorts of trinkets, Bellingshausen received lobsters and taro bulbs. However, the Russian seafarers rejected the fermented popoi on offer as inedible. Bellingshausen described the warriors as "strong and robust, but without a tattoo". A striking feature, as he had previously visited the islands of New Zealand and Nuku Hiva , whose warriors were lavishly and artistically tattooed. Bellingshausen was "disturbed by the wildness and relentlessness in all facial features".

mission

In July 1825, the Tahitian cutter Snapper of the London Missionary Society (LMS) landed on Rapa under Captain Shout (Shant according to other sources). When the ship sailed again, two men, Paparua and Aitareru, from Rapa were on board. They received religious instruction and a rudimentary schooling in Tahiti from the missionary John Davies. In October 1825 they returned to Rapa Iti, accompanied by two Tahitians and laden with gifts. Her description of the wealth of the Europeans in Tahiti prompted Chief Teraau (also Terakau or Teranga) to invite further missionaries. In January 1826, Brig Governor Macquarie brought four LMS missionaries to Rapa, armed with seeds, tools, lumber for a chapel and Bibles in Tahitian. The first mission station was set up in Ahurei Bay. The missionary work fell on fertile ground, since since the visit of the Snapper many natives had died of infectious diseases and the missionaries were able to persuade the chiefs that this was a punishment for worshiping the old gods. In April 1829, missionaries Pritchard and Simpson visited Rapa Iti and found that four chapels had already been built and that the residents were following the religious instructions with "an enjoyable attention."

The malacologist Hugh Cuming arrived in Rapa on May 17, 1828. His private research yacht Discoverer was four days offshore. Only a rough brief description of the fortifications is published by Cuming, as he was mainly interested in the island's molluscs .

Blackbirder

In 1862 a two-year raid by so-called " Blackbirders " began, who abducted more than 3500 inhabitants of several South Pacific islands as enslaved workers to Peru and Chile. In December 1862, a fleet of five ships anchored in Ahurei Bay. A large group of armed men was brought ashore to use force to capture workers. But the residents withdrew to the inaccessible mountain fortresses and the Blackbirders had to leave without having achieved anything.

A few days later an incident occurred in which the schooner Cora from Peru was involved and described Rear Admiral de Lapelin, the commander of the French Pacific Fleet, in a letter dated February 21, 1863 to the Ministry of Justice in Paris. Captain Aguirre, the commander of the Cora , was only able to recruit two contract workers on Easter Island (Rapa Nui) and therefore sailed on to Rapa Iti Island to recruit more workers there. In view of the ship, however, the inhabitants fled back to their mountain fortresses. Thirteen chiefs gathered and decided to hijack the ship and crew. A group of warriors sneaked aboard the Cora at night and arrested the captain and officers. The team surrendered without resistance. The Cora sailed to Tahiti, the ship and crew were handed over to the French authorities. Five sailors decided to stay on Rapa Island as guests. A later attempt by the Bark Misti to capture labor on Rapa Iti was abandoned when the captain learned of the Cora's fate .

The original population of Rapa, as the missionary John Davies estimated in 1826, was around 2,000. Between 1824 and 1830, 75% of the indigenous people died of infectious diseases brought in by European visitors - sandalwood hunters (there were hardly any sandalwood on Rapa Iti), pearl fishers and whalers. When Davies returned to Rapa in 1831, 600 Polynesians were still living on the island; five years later there were only 453.

After international protests and after the intervention of the French government - the traffickers had also struck out on islands of the Marquesas and Tuamotus, which were under French protectorate - the recruitment finally stopped. In the autumn of 1863 the Polynesians who were still alive were brought back to their homeland on the ship Barbara Gomez on the instructions of the Peruvian government . Little consideration was given to the origins of the people, because sixteen were stranded on Rapa Iti. At least one of them had contracted smallpox and caused a devastating epidemic on the island that killed many islanders. In 1867 the entire population was only 120 people.

Modern times

After the Pomaré dynasty had consolidated their influence on Tahiti with British support (and arms) and Pomaré II had been crowned king in 1819, he decided to extend his sphere of influence to the Austral Islands. So Rapa Iti suddenly found itself, although inhabited by independent tribes, under the hegemony of Tahiti. In 1867 the island was placed under French protectorate and finally annexed on March 6, 1881.

The British historian Katherine Routledge wanted to make a stopover on Rapa Iti in 1921, coming from Easter Island or Pitcairn, because she had heard of the ancient fortifications. However, her yacht Mana was unable to land due to bad weather and unfavorable winds.

From April 1921 to January 1922, the Australian-born archaeologist John Stokes of the Bernice P. Bishop Museum stayed with his wife Margaret Stokes on Rapa Iti as part of the Bayard-Dominick expedition to the Austral Islands. However, his research results were never published.

In 1956, Thor Heyerdahl and the Greenland trawler Christian Bjelland brought further scholars, the American anthropologist William Theodore Mulloy and the ethnologist Edwin N. Ferdon, to Rapa Iti as part of the “Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific” . The Heyerdahl expedition's merit for exploring Rapa Iti is the hitherto unknown scientific thoroughness with which the investigations and excavations at Morongo Uta were carried out, using the latest methods of the time, for example stratigraphic excavations and radiocarbon dating. Heyerdahl wanted to prove connections between Easter Island and Rapa Iti.

Economy, transport, administration and education

The islanders live from subsistence farming . There is no tourist infrastructure with hotels and restaurants.

Rapa Iti was once a stopover on the main line between Panama and New Zealand during the heyday of sailing and steam shipping, but is now outside of all shipping lines. An expedition cruise ship seldom goes to the island and its passengers have to be disembarked. Rapa does not have an airfield because there is no flat land suitable for construction. The island can therefore only be reached with the irregular supply ship or with a private yacht. There is no continuous ring road, only short stretches of road in the immediate vicinity of the villages. The two villages are connected by an only partially paved road, which becomes impassable when it rains, which is not uncommon. The connection is therefore mainly maintained with boats.

Politically, Rapa Iti, together with the uninhabited Marotiri , is one of five communities on the Austral Islands ( Communes des Îles Australes ) and has 515 inhabitants (as of 2017). The main town and administrative seat is Ahurei. The island is administered by the subdivision ( Subdivision administrative des Îles Australes ) of the High Commission for French Polynesia ( Haut-commissariat de la République en Polynésie française ) in Papeete on the island of Tahiti.

In Ahurei there is a post office (at the same time a bank), a primary school and a health center, which is only occasionally visited by a doctor from Tahiti, as well as a church with an attached parish hall in both villages. Electricity is generated with diesel generators and is not always available. The children attend secondary schools on the island of Tubuai, 700 kilometers away .

language

Rapa Iti has its own language, which has developed independently due to the island's relative isolation and which differs significantly from the dialects of the other Austral Islands. It is called Reo Rapa, or Rapan for short, sometimes also Reo Oparo, and with only about 300 speakers it is severely threatened, as it is being displaced more and more by Tahitian, and in official use also by French. It belongs to the east-central Polynesian language family and now also contains parts of the vocabulary of Marquesan or the Tahiti language.

cards

The lack of a landing facility for planes has long made it difficult to create a detailed topographical map of the island. In 2009 the first map in the scale range 1: 5000 was created from satellite images.

See also

literature

- F. Allan Hanson: Rapan Liveways. Society and History on a Polynesian Island. 1970, ISBN 0-88133-029-9 .

- Douglas Kennett, Atholl Anderson, Matthew Prebble, Eric Conte, John Southon: Prehistoric human impacts on Rapa, French Polynesia. (pdf, 477 kB) In: Antiquity 80 (2006). May 6, 2006, pp. 340-354 (reproduced on the Pennsylvania State University website).

- Matthew Prebble, Atholl Anderson, Douglas J Kennett: Forest clearance and agricultural expansion on Rapa, Austral Archipelago, French Polynesia. In: The Holocene. 23, 2012, p. 179, doi : 10.1177 / 0959683612455551 .

- Atholl Anderson, Douglas J. Kennett (Eds.): Taking the High Ground: The archeology of Rapa, a fortified island in remote East Polynesia. (pdf, 5.6 MB) Terra Australis, Volume 37. ISBN 978-1-922144-24-9 , 2013 (English).

Web links

- 1927 map (by Lawrence John Chubb)

- Ines Hielscher: Rapa Iti Island: One island, two villages, no hotel. In: Spiegel Online . 15th October 2018 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at

- ↑ Climate Data

- ^ Dieter Mueller-Dombois , F. Raymond Fosberg: Vegetation of the Tropical Pacific Islands , Springer-Verlag, New York-Berlin 1998, ISBN 0-387-98313-9 , pp. 402-404

- ^ Minster, JB and Jordan, TG: Present-day plate motions . In: Journal of Geophysical Research . tape 83 , 1978, pp. 5331-5354 .

- ↑ Mayes, CL, Lawver, LA and Sandwell, DT: Tectonic history and new isochron chart of the South Pacific . In: Journal of Geophysical Research . tape 95 , 1990, pp. 8543-8567 .

- ^ Duncan, RA and McDougall, I .: Linear volcanism in French Polynesia . In: Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research . tape 1 , 1976, p. 197-227 .

- ↑ Dupuy, C. et al. a .: Subducted and recycled lithosphere as the mantle source of ocean island basalts from southern Polynesia, central Pacific . In: Chemical Geology . tape 77 , 1989, pp. 1-18 .

- ^ Atholl John Anderson et al. a .: Prehistoric Human Impacts on Rapa, French Polynesia . In Researchgate , June 2015, [DOI: 10.1017 / S0003598X00093662] (German short version here: [1] )

- ^ Patrick Vinton Kirch: Rethinking East Polynesian Prehistory. Journal of the Polynesian Society No. 95, 1986, pp. 9-40

- ^ John FG Stokes: Ethnology of Rapa . Unpublished manuscript from the Bernice P. Bishop Museum, Honolulu 1930. Quoted from: Atholl Anderson, Douglas J. Kennett (Eds.): Taking the High Ground - The archeology of Rapa, a fortified island in remote East Polynesia. Terra Australis 37. Canberra 2012, pp. 47-76.

- ^ A b Archeology of Coastal Sites on Rapa . In: Atholl Anderson, Douglas J. Kennett (eds.): Taking the High Ground - The archeology of Rapa, a fortified island in remote East Polynesia , Terra Australis 37, Canberra 2012

- ^ Atholl Anderson: Dwelling carelessly, quiet and secure - A brief ethnohistory of Rapa Island, French Polynesia, AD 1791–1840. In: Terra Australis 37, Canberra 2012, p. 43

- ^ A b George Vancouver: A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean and Around the World , Volume 1, London 1798

- ↑ John Vine Hall: On The Island of Rapa . Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand 1868-1961, Volume 1, Wellington 1868, pp. 128-134

- ^ Douglas Kennett, Sarah B. McClure: The Archeology of Rapan Fortifications . In: Terra Australis 37, Taking the High Ground - Archeology of Rapa a Fortified Island in Remote Polynesia, Australian National University, Canberra 2012, pp. 203-234

- ^ William Mulloy: The fortified village of Morongo Uta . In: Thor Heyerdahl, Edwin Ferdon: Reports of the Norwegian Archaeological Expedition to Easter Island and the East Pacific . Volume 2, Gyldendal, Copenhagen 1965, pp. 23-68

- ↑ Te Rangi Hiroa (Sir Peter Buck Henry): Vikings of the Sunrise. Whitcombe and Tombs Limited, Wellington 1964 (new edition), p. 184

- ↑ Patrick Vinton Kirch: The Evolution of Polynesian Chiefdoms , Cambridge University Press, 4th Edition 1996, pp. 211-213

- ^ Glynn Barratt: Russia and the South Pacific 1696-1840. Volume 2, University of British Columbia Press, Vancouver 1988, ISBN 0-7748-0305-3 , pp. 199 f.

- ^ Robert W. Kirk: Paradise Past - The Transformation of the South Pacific, 1520-1920. Mc Farland & Co., Jefferson 2012, ISBN 978-0-7864-6978-9

- ^ Henry Evans Maude: Slavers in Paradise. University of the South Pacific Press, Suva (Fiji) 1986, pp. 39-41

- ↑ Théodore de Lapelin: L'Ile de Paques (Rapa-nui). In: Revue maritime et coloniale, Volume 35, November 1872, pp. 526-544

- ^ John Davies: The History of the Tahiti Mission 1799-1830. Hakluyt Society, Cambridge 1961, p. 331

- ^ Robert W. Kirk: Paradise Past - The Transformation of the South Pacific, 1520-1920. Mc Farland and Company Inc., Jefferson North Carolina, ISBN 978-0-7864-6978-9 , p. 158

- ^ Thomas Bambridge: La terre dans l'archipel des îles Australes - Étude du pluralisme juridique et culturel en matière foncière. Ed .: Au vent des îles, 2013, ISBN 978-2-915654-41-7 , p. 78

- ↑ Institut Statistique de Polynésie Française (ISPF) - Recensement de la population 2017

- ^ Mary E. Walworth: The Language of Rapa Iti: Description of a Language In Change (dissertation). University of Hawaii at Manoa Print, Honolulu 2015

- ↑ digital-geography.com: Rapa Iti, the treasure island , July 27, 2013, loaded on August 23, 2018