Blackbirding

Blackbirding or Blackbird catching has been the name given to the forced recruitment of islanders from the South Pacific to work since the mid-19th century . Melanesians and Micronesians native to the western South Pacific were preferred to plantations in Australia and the Fiji and Samoan islands . Polynesians from the eastern South Pacific were mostly brought to Peru and the Kingdom of Hawaii . In addition, a large number of islanders were brought on board European ships for fishing and seafaring services. A core element of the practice was the use of deception, threats and violence in recruiting.

International protests in the employing countries triggered extensive legal regulation of trade with Pacific islanders as workers, which ultimately ended blackbirding . The prosecution has seen spectacular court cases.

In English missionary societies and the Royal Navy was blackbirding on suspicion of slave trade . Whether the comprehensive system of indentured labor , which was served with blackbirding , was a late form of slavery is still a matter of dispute.

Methods

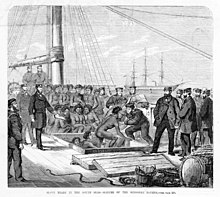

All forms of blackbirding show elements of physical violence, extortion or deception to varying degrees. In encounters at sea, canoes with islanders were often taken over the bow and rammed in order to then simulate a rescue operation and get the occupants on board. Here captains or recruiters seduced them into signing a contractual obligation to work on the plantations, or made them incapacitated through threats, physical violence, the administration of alcohol or opium and imprisoned them with leg irons.

There were manhunts on Pacific islands to gain labor, as well as cases of robbery and extortion. Often individual dwellings or entire villages were burned down, with which island rulers or heads of families were supposed to be forced to hand over tribal members to the recruiting captains or ship crews.

There was the so-called missionary trick , the invention of which is attributed to recruiter Henry Ross Lewin on Tanna (New Hebrides) or his accomplice John Coath:

"... traders dressing in cassocks and surplices, and, in the guise of peaceful missionaries, entrapping the natives into approaching their ship ..."

"... traders who, dressed in frocks and choir shirts, seduce natives under the guise of peaceful missionaries to approach their ship ..."

In a more subtle variant, recruiters sent a native sailor ashore in a missionary robe to simulate the possibility of a spiritual career for islanders and to lure them on board.

Clumsier deception took place during the clarification of the contents of the employment contract to be concluded, which was prescribed with the enactment of the Queenslander Pacific Island Laborers Act (1880) . According to a report by British Deputy High Commissioner for the West Pacific , Hugh Hastings Romilly, they could:

"... three outstretched fingers, depending on the skipper's mood, a 'contract duration' of three days, three months or three years [mean]."

Just as often, islanders were kept in the dark about the distance between their place of work and their home island. Deceptions about working conditions and times at the destination were common.

Taken in isolation , the conditions there are not an aspect of blackbirding , but of the comprehensive system of indentured labor . They also met those Pacific Islanders who had consciously and voluntarily entered into their employment contracts. The research also deals with questions of inadequate hygienic conditions during ship transports and high mortality during visits to plantations, separately from blackbirding in individual studies.

Beginning

In the course of abolitionism , there was a shortage of unskilled and heavy physical labor in almost all coastal regions of the Pacific, especially the British colonies of these areas. In the Australian colonies, the abolition of detention (1850–1868), another source of cheap labor, exacerbated the situation.

During the American Civil War (1861-1865) the availability of cotton decreased worldwide. British merchants welcomed new and regular sources of raw materials that could make them independent of imports from America. However, growing in the colony of Queensland, Australia without cheap labor was not considered profitable. Whaling crews with their ships laid free by the decline of the whaling industry , Australian bankrupts and refugees from the American Civil War who had taken refuge in Pacific islands found a lucrative field in the recruitment of such workers.

The entrepreneur and politician Benjamin Boyd made the first attempts to recruit auxiliary workers for Australia from 1847 to 1849. With the ships Portenia and Velocity , he introduced almost 200 residents of the Loyalty and Gilbert Islands to work in sheep shearing on farms in New South Wales . The action failed because there was hostility between the islanders as cheap competition and the existing staff. Human rights activists see the beginnings of a slave trade in the South Seas in this action, because the islanders were not recruited personally, but committed by agreements with the island rulers.

An agreement by MP and trader Captain Robert Towns marks the official start of imports of Pacific Islanders into the Queensland colony . In 1863 he hired the former sandalwood merchant Henry Ross Lewin on Tanna to recruit residents of the New Hebrides and Loyalty Islands as workers for his cotton plantations in Townsvale ( today : Veresdale and Gleneagle , both Queensland). The schooner Don Juan was converted for this purpose and sent from Brisbane on July 29, 1863 . Town's instructions to the captain, however, show that he resisted blackbirding :

"... I will on no account allow [these islanders] to be ill-used. They are a poor, timid, inoffencive race, and require all the kindness you can show them ... I will not allow them to be driven ... "

“… I will not under any circumstances allow [these islanders] to be mistreated. It is a poor, shy, peaceful breed, and it deserves all the kindness and kindness you can show them ... I will not allow them to be forced into anything ... "

On the way back one of the recruited islanders died; he was buried on Mud Island (Moreton Bay). The remaining 67, with which Brisbane was reached on August 17, 1863, are historically considered to be the first Pacific contract workers (indentured laborers) in Queensland.

According to Edward W. Docker, there are only indications that violence was used despite Town's instructions in a report by Captain William Blakes, HMS Falcon . An islander from Épi (New Hebrides) testified to him in 1867:

"... how a white man ... (Lewin, apparently?) Had battered one of the recruits to death with a stick."

"... like a white man ... (Lewin apparently?) Would have beaten one of the recruits to death with a stick."

In 1864 the Uncle Tom was the first repatriation of Pacific islanders who had fulfilled their contract of employment with Towns. In parallel to Uncle Tom , the Black Dog , an "ex-opium runner" , was used for further recruiting .

That same year, Fiji began recruiting in the Gilbert Islands. Coming from South America, the Ellen Elizabeth had already reached the archipelago the previous year. Under the command of a Captain Muller, who was supposed to procure workers for Peru , there had almost certainly been the first riots, deception and kidnappings. On the German side, thirty islanders were hired for the first time in 1864 for a twelve-month contract work on the plantations of the trading house Joh. Ces. Godeffroy & Sohn ( Samoan Islands ). They came from Rarotonga (Cook Islands). Nothing is known about the methods of their recruitment.

expansion

Between the 1860s and 1940s, the number of contract workers from the island peoples of the South Pacific was estimated to be close to one million. In addition, employers in the region hired around 600,000 Asian contract workers. Between 1884 and 1940 a total of up to 380,000 workers were brought to German New Guinea or the territory of New Guinea under Australian control , as well as 280,000 to British New Guinea . About 38,000 people worked on the plantations of the Solomon Islands between 1913 and 1940. Recruiting took place mainly in Melanesia , but also in Micronesia on the western and central Carolines . Recruits for South America or Hawaii were concentrated in Polynesia . Were shunned already evangelized islands, though exceptions are known.

Queensland

Between 1863 and 1906 a total of 64,000 South Pacific islanders came to Queensland for indentured labor (contract work). According to a study by Kay Saunders, the total number of all blackbirding victims who were deported to the colony and landed there amounts to around 1,000. Clive Moore, a historian at the University of Queensland at Brisbane, estimated that 15 to 20 percent of Queensland's initial diaspora had been abducted. The Australian Human Rights Commission estimates that a third of them were kidnapped or fraudulently lured to Australia.

Fiji Islands

About 16,000 Pacific islanders were brought to Fiji from other atolls and island groups between 1877 and 1911. Earlier transports are documented, but not sufficiently statistically recorded and published. For example, a report by the New Zealand governor George Ferguson Bowen mentions that as early as 1860, most of the ships calling into Fiji from New Zealand were chartered for the transport of so-called labor immigrants. The destination of these journeys is rarely clear.

Violent clashes with islanders in the contract labor trade in the Fiji Islands occurred especially from 1882 onwards when recruiting in New Britain , the Duke of York Islands and New Ireland . Initial proposals for the legal containment of blackbirding turned out to be pointless. In 1871, the British consul in Levuka, Edward March, considered his own draft reform to be impracticable.

After the relevant regulations were passed in Queensland, the port of Levuka was also used to disguise a blackbirding operated from Australia . To circumvent the restrictions of the Queensland Polynesian Laborers Act (1868), it became common practice to sail to Levuka with small cargo, secretly rename your ship and re-register with the resident British consul. This meant practical advantages, for Fiji's labor trade regulations were more lax than Queensland's. The following recruits were legally blackbirding ( officially : kidnapping ) because the secret renaming of a ship was illegal. The license for workers' trade issued in the actual home port was no longer valid, and a new one acquired in Levuka was no longer valid.

Parallel to the islanders of the South Pacific, up to 60,000 Indian workers were transported to Fiji for contract work from 1879 to 1916.

Samoa Islands

Transports of workers from the Pacific to the islands of Samoas are only partially recorded. It can be considered certain that between 1874 and 1877 about 200 Gilbertinsulans per year and between 1878 and 1881 about 475 Gilbertinsulans work on John's plantations . Ces. Godeffroy & Son were used. The German Trading and Plantation Society of the South Sea Islands in Hamburg (DHPG) , the successor to Godeffroysche trading and plantation operations, imported around 5,800 islanders as contract workers from the protected area of the New Guinea Company, or what would later become German New Guinea , between 1885 and 1913 . Statistically undocumented recruiting for the DHPG took place in the British part of the Solomon Islands and the Shortland Islands , among others . Estimates of the total number of workers brought to German / Western Samoa between 1884 and 1940 are 12,000.

For blackbirding in out of Samoa Workers Trade sources characterized the 19th century, a total negative image. The Australian political scientist and historian Stewart Firth considers the German system of contract labor to be generally inferior to the British one. The writer Jakob Anderhandt refers to James T. Proctor, one of the most brutal and most feared recruiters among islanders, who was employed by the Deutsche Handels- und Plantagengesellschaft . The South Sea merchant Eduard Hernsheim mentions in his memoirs that the DHPG , through lobbying in Germany, made the procurement of contract workers a "question of life". The German consul in Samoa was therefore inclined to proceed “not too strict” in the event of irregularities in worker traffic.

On the other hand, Oskar Stübel, as the German Consul General for the South Seas, emphasized at the time that until 1883 blackbirding ("excesses") on board German ships in the South Seas could not be proven. Most of the German captains in the trade had been familiar with the labor business "for years" and had given the consulate in Apia a "personal guarantee" for legal action. Only a later decision by German trading companies in Samoa to outsource labor recruitment and transfer it to contractually employed recruiters did the historian Sylvia Masterman see the decline of this impeccable practice.

Peru

After slavery was abolished in Peru (1854), cheap labor for cultivating one's own plantations and mining guano on the Chinchain Islands was not easy to come by. Between 1862 and 1863, Peruvian and Chilean Blackbirds brought 3,630 mostly Polynesian islanders to the port of Callao. In 1864 they operated as far as the sea areas west of Tahiti .

Reliable details of evacuated residents only exist for Easter Island . From her, between 1400 and 1500 Rapanui (or 34% of the estimated population) were taken on board. About 550 were victims of blackbirding . In the unfamiliar climate of Peru, a significant number of them died of infectious diseases. The French chargé d'affaires in Lima then prompted the diplomatic corps to issue a note to the prime minister protesting against the import of workers. Under international pressure, the country repatriated fifteen survivors to Easter Island, where they introduced smallpox . Most of the inhabitants who had stayed there died of the epidemic by 1864.

Oahu

From 1859 workers were transported to a lesser extent in the Pacific for use on the sugar cane plantations of Oʻahu (Kingdom of Hawaii). Between 1877 and 1887 around 2,400 islanders, mostly Polynesians, were brought here.

Violent conflicts between crews of Hawaiian laborers and islanders to be recruited were common, but according to historian Judith Bennett, they were less severe than in the Queensland and Fiji contracting trade. Bennett sees one of the main reasons for the presence of Hawaiian missionaries in the recruiting areas, where the clergy are critically monitoring, if not disapproving, the labor recruitment. Another reason was the Hawaiian government's fear of criticism from Great Britain and France. The recruitment could also be positively influenced by a subsidy initiated by the government.

Other contract workers in Hawaii came from China (from 1852), Japan (from 1868), Portugal (from 1878), Scandinavia (1880–81) and Germany (1880–97). In 1946 the recruitment process officially ended here.

statistics

Reliable quantitative statements about transports for the purpose of the work obligation are hardly possible because of the incomplete source situation. In addition to official journeys in the South Pacific, including known blackbirding cases, there was also notable worker smuggling. In the case of Queensland, no estimates exist. Official records of work obligations did not begin here until 1863.

In the 19th century, there are no sources for recruiting Pacific islanders for fishing and shipping services in the Pacific due to the lack of practical possibilities for a survey. Tables of the relevant licenses from European shipowners or operators, the Lists of Vessels licensed… (Labor to be employed amongst Islands), have a certain informative value . One of the earliest lists covers the reporting period from 1876 to 1881.

Humanitarian protests

At the latest, the drastic drop in recruitment for Peru drew the attention of humanitarian organizations to the Pacific labor trade. According to historian Jane Samson , one driving force for missionaries in the Pacific to report unfair recruitment practices by ship captains and crews was covert competition between mission societies and ship crews for oceanians willing to travel and work. Overall, there was a suspicious attitude. An early series of letters of protest submitted by representatives of various mission societies to the governments of the Australian colonies stated in general terms that labor recruitment in the Pacific:

"... could be nothing else than the victimization of helpless islanders ..."

"... nothing else could be than sacrificing helpless islanders ..."

The assassination of New Zealand Bishop John Coleridge Patteson by Nukapu residents in September 1871 further polarized the debate. The reason was that parts of the Australian and New Zealand public believed the event to be an act of revenge against the kidnapping of five young men from Nukapus by Blackbirds. Instead of a factual dispute, it now came about that:

"... humanitarians rode the tide of public indignation in order to secure passage of protective legislation, and to ensure that its terms reflected their interpretation of events in the labor trade ..."

"... human rights activists rode on a wave of public outrage to ensure that preventive laws were passed and to be certain that their interpretation of events in the area of workers' trafficking was thereby met ..."

Members of the Royal Navy , who were also active in journalism, used this for their own purposes. They used public outrage as a stepping stone to give English warships expanded powers as a police force in the South Pacific. Critical positions in recent research assume that Captain George Palmer in particular was “obsessed” with the idea that labor recruitment in the South Pacific is fundamentally and without exception a slave trade. In his book Kidnapping in the South Seas (1871) he deliberately cited particularly “hair-raising” (exaggerated) statements from missionaries and gave much that he only knew secondhand the “paint of the self-experienced” in order to curb labor recruitment to be able to demand.

With this, Palmer joined a tradition of publicly effective naval commanders who, on the one hand, were caught up in the idea of the innocent, naive and defenseless Pacific islander and, on the other hand, that of the brutal, morally inferior and unscrupulous European in the South Seas. In retrospect, both times were clichés that were one-sided and wrong.

Legal measures

In 1824 the slave trade at sea was declared a piracy by the British. Until new, adapted laws were passed, this regulation formed the only legal framework in which the Royal Navy - represented with six ships in Sydney Harbor since the 1860s - could take action against blackbirding in Pacific waters. Subsequent justification of the recourse measures in court also depended on how British commanders were able to interpret the offense of blackbirding (in British law of the time: kidnapping ) in terms of the slave trade and to interpret it as a violation of the slave trade legislation . One of the roots of the historical amalgamation of blackbirding and slavery lies in this particular legal reality .

In legal theory, only a minority of experts in the 1860s thought it possible to apply slave trade laws to cases of blackbirding . An effective conviction by an Australian court for violating such laws would also have admitted the existence of slavery in the colony (or its environs) and thus cast the colonial government itself in a crooked light before London. Against this background, the Queensland legislature in particular found itself in a position in which it had to choose a separate path independently of the London Parliament.

Following a complaint by the French government about raids by Queensland recruiters on New Caledonia and the Loyalty Islands, Queensland passed a first Colonial Law in March 1868 to regulate, but not restrict, trade with Pacific contract workers. The most important reasons for the Act to Regulate and Control the Introduction and Treatment of Polynesian Laborers were, according to the wording of the law: "... the prevention of abuses ..." ("... the prevention of abuse ...") by Pacific Islanders, but also: "... securing to the employer the due fulfillment by the immigrant of his agreement ... "(" ... to ensure the proper fulfillment of the agreement by the immigrant for his employer ... ").

A means of punishing irregularities in the recruitment process was only found in 1872 with the Pacific Islanders Protection Act , which was passed in London. In the run-up to this imperial law ( Imperial Law , valid throughout the British Empire or for all British citizens), Bishop John Coleridge Patteson in particular once again made it clear that recruiters and captains on workers' ships operated "in the spirit of slave traders" if they did not even have one I understood half a dozen words of the island dialects and therefore misunderstandings and escalating conflicts arose when recruiting.

The outrage over Patteson's violent death ultimately led to a public address by New Zealand Prime Minister William Fox , in which he asked for legal action from London. Following the arguments of the assassinated Pattesons, Queen Victoria described the new law as a measure in her speech from the throne in 1872:

"... to deal with ... practices, scarcely to be distinguished from slave trading."

"... to take action against ... actions that can hardly be distinguished from the slave trade."

Simultaneously with the enactment of the law, the construction of five smaller war schooners was approved, which were added to Australia Station and used to monitor labor recruitment in the South Pacific.

In practical terms, however, it was not possible to contain cases of blackbirding or kidnapping over the next eight years . John Crawford Wilson, new Commodore of Australia Station in Sydney, noted in an 1880 report published by the New South Wales government:

“… That where the native is recruited for the Fisheries, Guano Islands, or such like purposes, and when no Government agents [who monitor compliance with the laws] are present or checks of any kind placed on the masters or crews of these vessels, such practices as a means of getting cheap labor are as likely as not to exist. "

“... that wherever the native is being recruited for fishing, guano islands or the like, and when there are no government agents present [to ensure compliance with the law] or the commanders or crews of these ships are not controlled in any way that such practices are just as likely to exist as a means of getting cheap labor as their non-existence. "

In the legal reality, the monitoring of anti- kidnapping laws by government agents on board workers' ships also fails. Like captains and crews, most of these agents are "unable" to communicate with islanders in their dialects. When explaining employment contracts, one relies heavily on local interpreters; But they received a commission for every recruited islander and did not take the truth very seriously.

Further riots in the recruiting of workers, especially on the islands north of New Guinea, led to the convening of a Royal Commission in January 1885 . Their investigations were followed in June 1885 by an early repatriation of 404 Pacific workers in Queensland who, according to the findings of the commission, had not been adequately informed about their working conditions and their place of work. Two months later, the government of Sir Samuel Griffith passed a resolution to cease imports of Pacific contract workers at the end of 1890. In 1892 a brief resumption followed, which, however, politically and publicly did not prove tenable.

Final phase

The final cessation of the transportation of Pacific islanders for the purpose of providing labor is based on a variety of reasons. Spectacular and court-negotiated blackbirding cases led to a loss of reputation from 1871, which is why the encompassing system of indentured labor also had to deal with resistance.

In the case of Queensland, working islanders were perceived as undesirable competition and stigmatized by the White Australian population. This development intensified through the economic crisis (1890) and the collapse of the sugar industry (1892).

After Queensland joined the new Australian community of states , the Pacific Island Laborers Act (1901) was passed in the same year , according to which workers from the Pacific Islands had to leave Australia by December 31, 1906. Islanders who came to the continent before September 1, 1879, as well as those who were employed on ships, were not covered by this law.

The Pacific Islanders' Fund was established to pay outstanding wages and to finance repatriation after the contract period has expired . However, funds from the fund were embezzled by the government. They were used to pay for the Australian administrative apparatus for the system of indentured labor and for the deportation of Pacific islanders under the Pacific Laborers Act (1901) and the new White Australia Policy . The deportations ended in 1906. Few Pacific Islanders remained in Australia. Descendants of those affected estimated in 2013 that the embezzled funds had now run to an amount of 30 million Australian dollars (at that time about 19.5 million euros).

In Fiji, an alternative importation of labor from India began in May 1879. The recruitment of Melanesian workers, on the other hand, declined and was completely discontinued in 1911.

In Kaiser-Wilhelmsland and the Bismarck Archipelago , the recruitment of workers was only gradually withdrawn, but in principle and on a political level. In the years 1911–13, the governor for German New Guinea, Albert Hahl , issued the first ordinances that prohibited recruiting on smaller islands. For this, Hahl risked a conflict of interest with local planters and entrepreneurs. In addition, Hahl campaigned for the abolition of the privileges of the German Trading and Plantation Society (DHPG) in the recruiting of workers for German Samoa. However, he was unsuccessful with this initiative. In German Samoa, the beginning of the First World War and the loss of German New Guinea as a colonial territory finally led to the end of Melanesian contract work.

Concept history

English

The term goes back to blackbird , in British English the term for blackbird or black thrush (Turdus merula) . A transfer of the color of the plumage to the skin color of black Africans or Aborigines is obvious, but how blackbirding developed from this is unproven. The blackbird shooting , the manhunt in the 19th century on members of the Australian indigenous population by early European settlers, is regarded as a link . In particular, the connotation that it was a kind of “sport” (“ sporting activity”) flowed into blackbird catching in a similar way .

In 1836 the New York weekly newspaper The Emancipator , which journalistically combated slavery, cited blackbirding as a term. In the 1860s the evidence for the area of the Atlantic becomes denser. The US Supreme Court upheld a guilty verdict in 1864 because , according to a testimony, the barque Sarah wanted to go black-birding from New York to West Africa in 1861 . In an adventure novel by the English author Henry Robert Addison from 1864, a ship "blackbirding" off the coast of West Africa saves the protagonist from shipwreck. In 1873 the English playwright Colin Henry Hazlewood wrote the "romantic drama" Blackbirding, or, the filibusters of South America.

Since the 1870s the term occurs especially for Australia and the South Seas. An early entry in a dictionary is the inclusion in the English slang dictionary 1870, where blackbird-catching is explained with the slave trade. According to the edition of 1873, the word is already used “nowadays mainly for the Polynesian coolie trade”. An early mention of blackbirding with reference to the Pacific island world is also found in the Narrative of the Voyage of the Brig Carl (1871) . A distinction is already made here between various methods of labor recruitment - those that were “just and useful”, those of suspicious character and finally those that ultimately were about "robbery and murder" ("robbery and murder"). In this early period was but always to the activity as such, irrespective of the method of the term "black-birding" or "blackbird catching" ( mutatis mutandis : "catching of black birds") has been applied.

Newer dictionary entries also show a range of meanings. The Australian Macquarie Dictionary from 2009 sees in blackbirding :

"... the practice of employers in Australia (also Fiji and Samoa) of recruiting Pacific islander people ... as laborers, often by kidnapping them or by the use of force ..."

"... the practice of employers in Australia (also in Fiji and Samoa), Pacific Islanders ... to recruit as workers, often through kidnapping or the use of force ..."

The 2005 Oxford Dictionary of English historically defines the blackbird as:

"... black or Polynesian captive on a slave ship ..."

"... black or Polynesian prisoners on a slave ship ..."

The 1981 Historical Dictionary of Oceania describes the practices in a generalized way under labor trade . This is:

"... the system of indentured labor, developed as a scaled-down but legal replacement of slave labor ..."

"... the system of contract labor, developed as a weakened but legal substitute for slave labor ..."

The online edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica describes blackbirding as:

"... practice of enslaving (often by force and deception) South Pacific islanders on the cotton and sugar plantations of Queensland, Australia (as well as those of the Fiji and Samoan islands) ..."

"... [the] practice of enslavement of islanders of the South Pacific (often with the use of deception and violence) on the cotton and sugar cane plantations of Queensland, Australia (as well as those of the Fijian and Samoas archipelagos) ..."

Of English-language authors such as the historian Gerald Horne or the labor researcher Edward D. Beechert , as well as by the Australian Human Rights Commission , is blackbirding frequently used as a synonym for slave trade in the area of the Pacific. The conceptual proximity is also reflected in the titles of popular books on the subject, such as the 1935 Slavers of the South Seas by Australian publicist Thomas Dunbabin .

German

A ship used to transport workers is referred to in German and English literature as a "Blackbirder". The colonial writer Stefan von Kotze used the expression “Schwarzdroßler” as the German equivalent . The shipping historian and captain Heinz Burmester spoke of “Blackbirders” as people who were involved in the trade (“illegal recruiting”) . According to him, the word "Küstern" was in use for activities on German ships. The writer Jakob Anderhandt also describes the people involved as "Schwarzdroßler" and refers to the English designation of origin "black bird catcher" .

In the more recent German specialist literature, blackbirding is defined indirectly. The ethnologist Hermann Mückler sees the phenomenon as a "violent [...] abduction of mainly Melanesian Pacific islanders on sugar cane plantations in Queensland" and understands the boundaries between "contract work" (indentured labor) and slave trade as "fluid". At the same time, however, Mückler considers a view of the system of indentured labor as merely compulsory recruitment to be one-sided and in need of relativization: “There were certainly also islanders who voluntarily embarked on this adventure, although of course they could not know what hardships they were taking on . ”In a biography of the South Sea merchant Eduard Hernsheim , Jakob Anderhandt works out that even 19th century Germans were able to understand blackbirding as a“ pure slave trade ”. For Hernsheim they were excesses of the workers' trade operated by Queensland, which had developed "without knowledge and against the laws of the Australian colonial governments".

Evaluation as slavery

The question of whether Pacific islanders were mainly properly recruited as workers for plantations or whether they were kidnapped, i.e. victims of blackbirding , remains a matter of debate to this day. It is certain that kidnapping / blackbirding occurred with great frequency in the first ten to fifteen years of the contract labor trade . To what extent it is in the whole system of indentured labor to (work commitment) slavery acted, is still debated in Australia.

The contemporary anthropologist Nikolai Nikolajewitsch Miklucho-Maklai already described the entire labor trade as the slave trade and the labor obligations as slavery . The employer, unlike the owner of a slave, would have no economic interest in his contractual partner being able to work beyond the obligation. He forces the employee to spend, pays little attention to his diet and hardly cares about him in the event of illness. That is why contract work has even greater disadvantages for those obliged to work than enslavement.

On the other hand, the German Consul General for the South Seas, Oscar Stübel , refused to refer to workers' trade as "the hidden slave trade". The crucial difference lies in the fact that “the workers are transported back free of charge after the contract period has expired” and their use is “checked as closely as possible” during the contract period. The contract worker’s situation does not worsen as a result of the work stay, but changes for the better because of the possibility of absorbing “elements of civilization”.

More recently, historian Clive Moore has suggested that slavery is defined by possession, purchase, sale, and lack of wages. In the system of indentured labor , on the other hand, contracts were concluded and work was paid. As a further indication of the correctness of his thesis, Moore sees the fact that many islanders have decided to go to work again after returning home. Slavery is a term used by the Pacific Islanders to emotionally describe the processes and feelings prevailing at the time. Factually, however, it does not apply. Nevertheless, the system of indentured labor as a whole was motivated by exploitation. Those affected by him had lived under slave-like and racial conditions.

How difficult it was for contemporaries to get facts about the system was described by the scientist and explorer Benedict Friedländer in 1899: “Those who are interested say that everything is in perfect order; but those who envy the planters tell horror stories. There are hardly any uninterested people who are also knowledgeable about the subject, and the cautious reporter has to leave it to an ignoramus . "

In retrospect, it is only comparatively seldom possible to decide to what extent the free will of an islander was impaired or physical coercion was exercised. Among other things, this has to do with the fact that the power of the government agents on board the workers' ships , which were supposed to monitor compliance with the anti- kidnapping laws, was strictly limited. Minor violations could hardly be proven in court. Agents who threatened retaliatory measures for this made themselves ridiculous in front of the crew and the captain - or later in the process. So they often failed to take such steps. Corresponding sources reflect the historical reality incompletely and paint a picture that is too positive. The agents themselves also had a vital interest in bringing as much manpower as possible to the colony they worked for.

Attempts at coping

Pacific Islanders who remained in Australia became politically active in the 1970s and were recognized as a national minority in 1994. In 2013, this group included around 40,000 people. For injustices suffered such as blackbirding , misappropriated financial means and deportations in pursuit of the White Australia Policy, their representatives expect compensation and are hoping for an official apology from the Australian government. In their views they are supported by the governments of the Solomon Islands and Vanuatus. Australia has not yet followed such wishes and demands.

In 2008, UNESCO nominated the Pacific Slave Route as part of its Slave Route Project for inclusion in the World Document Heritage .

See also

literature

- Jakob Anderhandt: 'De facto the pure slave trade' and courageous men . In: ders .: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, pp. 75–130.

- Edward W. Docker: The Blackbirders. A Brutal Story of the Kanaka Slave Trade . Angus & Robertson, London 1981, ISBN 0-207-14069-3 .

- Thomas Dunbabin: Slavers of the South Seas . Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1935.

- Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby.

- Henry Evans Maude : Slavers in paradise. The Peruvian slave trade in Polynesia, 1862–1864. Stanford University Press, Stanford 1981, ISBN 0-8047-1106-2 .

- Reid Mortensen: Slaving in Australian Courts: Blackbirding Cases, 1869-1871 . In: Journal of South Pacific Law , vol. 4 (2000), no pagination, core.ac.uk (PDF)

- Hermann Mückler: Blackbirding . In: ders .: Colonialism in Oceania . Facultas, Vienna 2012, p. 140.

- Jane Samson: Imperial Benevolence: The Royal Navy and the South Pacific Labor Trade 1867–1872 . In: The Great Circle , vol. 18, no. 1 (1996), pp. 14-29.

- Deryck Scarr: Recruits and Recruiters: A Portrait of the Pacific Islands Labor Trade . In: The Journal of Pacific History , vol. 2, 1967, pp. 5-24.

Web links

- "Blackbirding" - The Slave System's Just-as-Evil Twin? In: Undercover Reporting , Text Collection, New York University

- Polynesian Laborers Act , 1868, [1] (PDF) also cited as Polynesian Laborers Act

- Pacific Islanders Protection Act , 1872, digitized (PDF)

- Pacific Islanders Protection Act , Amendment 1875 (PDF) qut.edu.au

- Ian Christopher Campbell: A history of the Pacific Islands . 1989, books.google.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ For example: Edward Wybergh Docker: The Blackbirders: A brutal story of the Kanaka slave-trade. (Queensland Classics Edition.) Angus & Robertson, Sydney, Melbourne u. a. 1981, p. 47, and Henry Evans Maude: Slavers in Paradise: The Peruvian labor trade in Polynesia, 1862–1864. Australian National University Press, Canberra 1981, p. 90.

- ↑ An early example of the latter can be found in: Henry Evans Maude: Slavers in Paradise: The Peruvian labor trade in Polynesia, 1862–1864. Australian National University Press, Canberra 1981, p. 44.

- ↑ See as one of the earliest cases the arrival of King Oscar , Kpt. Gibbins, before Epi ( New Hebrides ), Edward Wybergh Docker: The Blackbirders: A brutal story of the Kanaka slave-trade. (Queensland Classics Edition.) Angus & Robertson, Sydney, Melbourne u. a. 1981, p. 46.

- ↑ The Stanley incident describes this type of procedure in detail, cf. the presentation in German in: Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, pp. 106–119.

- ↑ Reid Mortensen: Slaving in Australian Courts: blackbirding Cases, 1869-1871. In: Journal of South Pacific Law , vol. 4 (2000), no pagination.

- ^ PJ Stewart, "New Zealand and the Pacific Labor Traffic, 1870-1874". In: Pacific Historical Review , vol. 30, no. 1 (1961), pp. 47-59, here: p. 53.

- ↑ Edward Wybergh Docker: The Blackbirders: A brutal story of the Kanaka slave-trade . (Queensland Classics Edition.) Angus & Robertson, Sydney, Melbourne u. a. 1981, p. 69.

- ↑ Quoted from: Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, p. 82.

- ↑ Cf. Hugh Hastings Romillys report (1883), cited in German translation in: Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, die Südsee und viel Geld . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, p. 134.

- ↑ See especially: Ralph Shlomowitz: Mortality and the Pacific Labor Trade. In: Journal of Pacific History , vol. 22, no. 1 (1987), pp. 34-55.

- ↑ Gerald Horne: The White Pacific: US Imperialism and Black Slavery in the South Seas after the Civil War . University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu 2007, ISBN 978-0-8248-3147-9 , p. 38 ff., Books.google.de

- ↑ Thomas Dunbabin: Slavers of the South Seas , Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1935, pp. 149–151.

- ↑ Jane Samson: Imperial Benevolence: The Royal Navy and the South Pacific Labor Trade 1867-1872. In: The Great Circle , vol. 18, no. 1 (1996), pp. 14-29, here: p. 16.

- ↑ Townsvale Cotton Plantation. (No longer available online.) Archived from the original on April 2, 2015 ; accessed on March 20, 2015 .

- ^ EV Stevens: Blackbirding: A brief history of the South Sea Island Labor Traffic and the vessels engaged in it. In: Journal [of the] Historical Society of Queensland , vol. 4, eat. 3 (1950), pp. 361-403, here: pp. 363 f.

- ^ EV Stevens: Blackbirding: A brief history of the South Sea Island Labor Traffic and the vessels engaged in it . In: Journal [of the] Historical Society of Queensland , vol. 4, eat. 3 (1950), pp. 361-403, here: p. 365, see also Brisbane Courier , August 18, 1863.

- ↑ Edward Wybergh Docker: The Blackbirders: A brutal story of the Kanaka slave-trade. (Queensland Classics Edition.) Angus & Robertson, Sydney, Melbourne u. a. 1981, p. 46.

- ↑ Edward Wybergh Docker: The Blackbirders: A brutal story of the Kanaka slave-trade. (Queensland Classics Edition.) Angus & Robertson, Sydney, Melbourne u. a. 1981, p. 42.

- ^ EV Stevens: Blackbirding: A brief history of the South Sea Island Labor Traffic and the vessels engaged in it . In: Journal [of the] Historical Society of Queensland , vol. 4, eat. 3 (1950), pp. 361-403, here: p. 366.

- ^ Henry Evans Maude: Slavers in Paradise: The Peruvian labor trade in Polynesia, 1862–1864 . Australian National University Press, Canberra 1981, p. 91.

- ^ Henry Evans Maude: Slavers in Paradise: The Peruvian labor trade in Polynesia, 1862–1864 . Australian National University Press, Canberra 1981, p. 90; see also: JA Bennett: Immigration, 'Blackbirding', Labor Recruiting? The Hawaiian Experience 1877-1887 . In: Journal of Pacific History , vol. 11, no. 1 (1976), pp. 3-27, here: p. 16.

- ^ Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford, 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby, p. 12.

- ↑ a b c d Paul Bartizan: Pacific Islanders to be used as cheap labor. Australian government prepares to revive “blackbirding”. In: World Socialist Website , November 3, 2003, online .

- ↑ Michael Köhler: Acculturation in the South Seas. The colonial history of the Caroline Islands in the Pacific Ocean and the change in their social organization. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1982, ISBN 3-8204-5763-1 (also dissertation, University of Marburg 1980), p. 230.

- ↑ Heinz Schütte: "A small step forward in cultural terms": Mission as modernization , in: Saeculum: Yearbook for Universal History , 64th year (2014), 1st half volume, pp. 73–89, here: sections on education for work , p 77 ff. And violence, obedience, forced labor , p. 86 f.

- ↑ Deryck Scarr: "Recruits and Recruiters: A Portrait of the Pacific Islands Labor Trade". In: The Journal of Pacific History , vol. 2 (1967), pp. 5-24, here p. 5.

- ↑ Kay Saunders: Uncertain bondage: an analysis of indentured labor in Queensland to 1907 with particular reference to the Melanesian servants , Dissertation, University of Queensland 1974, pp. 71-86.

- ^ A b c d Charmaine Ingram: South Sea Islanders call for an apology . In: Australian Broadcasting Corporation , Lateline, September 2, 2013.

- ↑ a b Tracey Flanagan, Meredith Wilkie, Susanna Iuliano: Australian South Sea Islanders. A century of race discrimination under Australian law , Australian Human Rights Commission , online .

- ^ A b Deryck Scarr: Recruits and Recruiters: A Portrait of the Pacific Islands Labor Trade . In: The Journal of Pacific History , vol. 2 (1967), pp. 5-24, here p. 5.

- ^ PJ Stewart: New Zealand and the Pacific Labor Traffic, 1870-1874 . In: Pacific Historical Review , vol. 30, no. 1 (1961), pp. 47-59, here: p. 48.

- ↑ Peter Corris: "Blackbirding" in New Guinea Waters, 1883-1884 . In: The Journal of Pacific History , vol. 3 (1968), pp. 85-105, here p. 89.

- ↑ Jane Samson: Imperial Benevolence: The Royal Navy and the South Pacific Labor Trade 1867-1872 . In: The Great Circle , vol. 18, no. 1 (1996), pp. 14-29, here: p. 18.

- ↑ Edward Wybergh Docker: The Blackbirders: A brutal story of the Kanaka slave-trade. (Queensland Classics Edition.) Angus & Robertson, Sydney, Melbourne u. a. 1981, p. 55.

- ^ Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford, 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby, p. 24.

- ^ Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford, 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby, p. 40.

- ^ Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford, 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby, p. 45.

- ^ Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford, 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby, p. 314.

- ↑ Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, p. 76.

- ^ Eduard Hernsheim: South Sea merchant: Collected writings . MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2014/15, p. 171.

- ↑ [Oscar Wilhelm Stübel]: Memorandum, concerning the German Trade and Plantation Society of the South Sea Islands in Hamburg. In: Hans Delbrück, Das Staatsarchiv: Collection of the official pieces of files on the history of the present. Founded by Aegidi and Klauhold , Volume 43, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1885, pp. 322–334, here p. 329.

- ^ Sylvia Masterman, The Origins of International Rivalry in Samoa: 1845-1884 . Allen & Unwin, London 1934, p. 76.

- ^ Brij V. Lal, Kate Fortune: The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia . Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press , 2000, ISBN 0-8248-2265-X , p. 208.

- ^ A b Henry Evans Maude: Slavers in Paradise: The Peruvian labor trade in Polynesia, 1862–1864 . Australian National University Press, Canberra 1981, p. 19 f.

- ^ A b Karl F. Gründler: Served islanders. The residents of Easter Island suffered from the slave trade and oppression . Deutschlandradio Kultur , April 5, 2007. Quoted from: Hermann Fischer: Shadows on Easter Island - A plea for a forgotten people. BIS Verlag, Oldenburg 1998, 248 pages, ISBN 3-8142-0588-X . The sources assume about 150 to 160 islanders as the total surviving population.

- ^ Jean Ingram Brookes: International Rivalry in the Pacific Islands, 1800-1875 . University of California Press, Berkeley / Los Angeles, 1941, p. 295.

- ^ A b Niklaus Rudolf Schweizer: Hawaiʻi and the German-speaking peoples. Bern / Frankfurt am Main / Las Vegas 1982.

- ^ JA Bennett: Immigration, 'Blackbirding', Labor Recruiting? The Hawaiian Experience 1877-1887 . In: Journal of Pacific History , vol. 11, no. 1 (1976), pp. 3-27, here p. 17.

- ↑ a b Edward D. Beechert: Working in Hawaii: A Labor History. University of Hawaii Press, 1985, ISBN 0-8248-0890-8 , pp. 77, 81, books.google.de

- ^ JA Bennett: Immigration, 'Blackbirding', Labor Recruiting? The Hawaiian Experience 1877-1887 . In: Journal of Pacific History , vol. 11, no. 1 (1976), pp. 3-27, here p. 6.

- ↑ On contract workers recruited in Scandinavia and Germany see: Ralph Simpson Kuykendall: The Hawaiian Kingdom , Volume 3 (that is: 1874–1893: The Kalakaua dynasty ), pp. 133–135, ulukau.org

- ↑ Reid Mortensen: Slaving in Australian Courts: blackbirding Cases, 1869-1871 . In: Journal of South Pacific Law , vol. 4 (2000), no pagination.

- ↑ Jane Wessel: The Australian South Sea Islander Collection. In: Queensland State Archives: The Australian South Sea Islander Collection . 2013, here 2:10 min .

- ↑ Contained in: John Crawford Wilson: Labor Trade in the Western Pacific . Thomas Richards (Government Printer), Sydney 1881.

- ↑ Jane Samson: Imperial Benevolence: The Royal Navy and the South Pacific Labor Trade 1867-1872 . In: The Great Circle , vol. 18, no. 1 (1996), pp. 14-29, here: pp. 17 and 21.

- ↑ Jane Samson: Imperial Benevolence: The Royal Navy and the South Pacific Labor Trade 1867-1872. In: The Great Circle , vol. 18, no. 1 (1996), pp. 14-29, here: p. 17.

- ↑ Reid Mortensen: Slaving in Australian Courts: blackbirding Cases, 1869-1871. In: Journal of South Pacific Law , vol. 4 (2000), no pagination. Daily Southern Cross , editorial of November 1, 1871, natlib.govt.nz, accessed June 11, 2015.

- ↑ Jane Samson: Imperial Benevolence: The Royal Navy and the South Pacific Labor Trade 1867-1872 . In: The Great Circle , vol. 18, no. 1 (1996), pp. 14-29, here: p. 14.

- ^ First edition: Kidnapping in the south seas: being a narrative of a three months' cruise of HM Ship Rosario, by George Palmer , Edmonston and Douglas, Edinburgh 1871.

- ↑ Jane Samson: Imperial Benevolence: The Royal Navy and the South Pacific Labor Trade 1867-1872. In: The Great Circle , vol. 18, no. 1 (1996), pp. 14-29, here: pp. 19-22.

- ↑ Reid Mortensen: Slaving in Australian Courts: blackbirding Cases, 1869-1871. In: Journal of South Pacific Law , vol. 4 (2000), no pagination.

- ^ PJ Stewart: New Zealand and the Pacific Labor Traffic, 1870-1874 . In: Pacific Historical Review , vol. 30, no. 1 (1961), pp. 47-59, here: p. 49.

- ↑ Quoted in Reid Mortensen: Slaving in Australian Courts: Blackbirding Cases, 1869–1871. In: Journal of South Pacific Law , vol. 4 (2000), no pagination.

- ^ Deryck Scarr: Fragments of an Empire: a history of the Western Pacific High Commission, 1877-1914 . Australian National University Press, Canberra 1967, p. 37.

- ^ JC Wilson: Labor Trade in the Western Pacific . Thomas Richards (Government Printer), Sydney 1881, p. 1.

- ^ JC Wilson: Labor Trade in the Western Pacific . Thomas Richards (Government Printer), Sydney 1881, p. 4.

- ↑ Peter Corris: "Blackbirding" in New Guinea Waters, 1883-1884 . In: The Journal of Pacific History , vol. 3 (1968), pp. 85-105, here: pp. 100 f.

- ↑ Documenting Democracy at foundingdocs.gov.au ( memento of October 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on April 7, 2010.

- ^ Clive Moore: The Pacific Islanders Fund and the Misappropriation of the Wages of Deceased Pacific Islanders by the Queensland Government . In: University of Queensland , August 15, 2013, uq.edu.au ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ White Australia Policy. In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved January 15, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Catherine Graue: Calls for an official apology over 'blackbirding' trade on 150th anniversary. Australian Broadcasting Corporation, August 16, 2013, abc.net.au .

- ^ Museum Victoria: Our Federation Journey - A 'White Australia' ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) .

- ^ Brij V. Lal, Kate Fortune: The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. University of Hawaii Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8248-2265-X , p. 621.

- ↑ Oanda: Historical Exchange Rates . → 0.6500 as mean value for A $ / € 2013 → 24.7 million €.

- ^ Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford, 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby, pp. 217, 223-233; and Hermann Joseph Hiery : The Neglected War: The German South Pacific and the Influence of World War I . University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Stewart G. Firth: German Recruitment and Employment of Laborers in the Western Pacific before the First World War. (Thesis submitted for the degree of D. Phil., Oxford, 1973.) British Library Document Supply Center, Wetherby, pp. 206 f.

- ↑ Michael Quinion: Blackbirding . In: World Wide Words. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ↑ quoted from The first annual report of the New York committee of Vigilance, New York 1837, p. 51, online. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ↑ Cases ARGUED and adjudged in the Supreme Court of the United States, December Term, 1864, Volume 2, Washington 1866, p 375, online. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- ^ Henry Robert Addison: All at sea. London 1864, p. 205, online. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ↑ Colin Henry Hazlewood: Blackbirding, or, The filibusters of South America, no place 1873.

- ^ John Camden Hotten: The slang dictionary. London 1870, p. 75, online. Retrieved March 30, 2015.

- ↑ John Camden Hotten, The slang dictionary. London 1873, p. 84, quoted from the Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd edition 1989, sv blackbirding.

- ↑ Quoted in: Edward Ellis Morris: Austral English: A Dictionary of Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages . Cambridge Library Collection - Linguistics, Cambridge University Press, 2011, ISBN 1-108-02879-9 , p. 32. Retrieved March 10, 2015.

- ^ Macquarie Dictionary . 5th edition. Macquarie Dictionary Publishers, Sydney 2009, p. 174.

- ^ Oxford Dictionary of English . 2nd Edition, Revised. Oxford University Press, Oxford / New York 2005, p. 171.

- ^ Robert D. Craig, Frank P. King: Historical Dictionary of Oceania. Greenwood Press, Westport / London 1981, p. 152.

- ↑ Blackbirding. In: Encyclopædia Britannica . Retrieved January 15, 2020 .

- ↑ Gerald Horne: The White Pacific: US Imperialism and Black Slavery in the South Seas after the Civil War . University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu 2007, ISBN 978-0-8248-3147-9 , p. 259, books.google.de

- ^ Thomas Dunbabin: Slavers of the South Seas . Angus & Robertson, Sydney 1935.

- ↑ Stefan von Kotze: From Papuas Kulturmorgen: South Sea Memories , Berlin 1905, p. 118, quoted and taken over by: Jürgen Römer: “A picture of fairytale magic”. Germans in Finschhafen (New Guinea) 1885–1888 , online (PDF)

- ↑ Heinz Burmester: Captain Meyer and the Godeffroysche Bark Elisabeth on their last trips to the South Seas , in: Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv 6 (1983), pp. 65–89, here p. 72.

- ↑ Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, p. 76.

- ↑ Hermann Mückler: Colonialism in Oceania , Facultas, Vienna 2012, pp. 128 and 144 f.

- ↑ Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, pp. 75-102.

- ^ Eduard Hernsheim: South Sea merchant: Collected writings . MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2014/15, p. 665 f.

- ^ Multicultural in Queensland. The Australian South Sea Islander community . multicultural.qld.gov.au.Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ↑ Josepf Cheer, Keir Reeves: Roots Tourism: Blackbirding and the Sout Sea Islander Diaspora . Australia International Tourism Research Unit, Monash University , 2013, p. 246, quoted from: Matthew Peacock, Clive Moore: The Forgotten People: A History of the Australian South Sea Island Community. Australian Broadcasting Commission, Sydney 1979, ISBN 0-642-97260-5 , 95 pages; Wal F. Bird: Me no go Mally Bulla: Recruiting and blackbirding in the Queensland labor trade 1863-1906. Ginninderra Press, Charnwood (ACT) 2005, ISBN 1-74027-289-7 , 111 pages; Reid Mortensen: Slaving in Australian Courts: Blackbirding cases, 1869-1871 , Journal of South Pacific Law, 2000, pp. 1-19.

- ^ John Crawford Wilson: Labor Trade in the Western Pacific. Thomas Richards (Government Printer), Sydney 1881, p. 10, footnote “*”.

- ↑ [Oscar Wilhelm Stübel]: Memorandum, concerning the German Trade and Plantation Society of the South Sea Islands in Hamburg . In: Hans Delbrück, Das Staatsarchiv: Collection of the official pieces of files on the history of the present. Founded by Aegidi and Klauhold , Volume 43, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1885, pp. 322–334, here p. 328.

- ^ South Sea Islanders mark sugar 'slave' days . Special Broadcasting Service , March 26, 2014.

- ↑ Susan Johnson: Spirited Away. ( Memento of March 12, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) In: The Courier-Mail , QWeekend, 2013, pp. 19-21.

- ^ Benedikt Friedländer: Samoa . Westermann, Braunschweig 1899, p. 42.

- ^ Deryck Scarr: Recruits and Recruiters: A Portrait of the Pacific Islands Labor Trade . In: The Journal of Pacific History , vol. 2 (1967), pp. 5-24, here p. 12.

- ↑ For the example of the government agent William A. McMurdo (Queensland) see: Jakob Anderhandt: Eduard Hernsheim, the South Seas and a lot of money . Biography in two volumes. MV-Wissenschaft, Münster 2012, here: Volume 2, p. 106.

- ^ The Call for Recognition of the Australian South Sea Islander Peoples: A Human Rights issue for a 'Forgotten People' . University of Sydney , August 20, 2013, sydney.edu.au

- ^ Free forum to call for recognition of South Sea Islanders . University of Sydney, August 19, 2013.

- ^ Clive Moore: The Pacific Islanders Fund and the Misappropriation of the Wages of Deceased Pacific Islanders by the Queensland Government . In: University of Queensland , August 15, 2013, uq.edu.au ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Our Federation Journey - A 'White Australia' . ( Memento of April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Museum Victoria

- ^ Special Broadcasting Services: 150 years on, South Sea Islanders seek apology for Blackbirding . November 2, 2013.

- ^ Pacific Memories nominated for Memory of the World Register . ( Memento of April 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) UNESCO