Long-eared Owl

| Long-eared Owl | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Long-eared Owl ( Asio otus ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Asio otus | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The long-eared owl ( Asio otus ) is a bird art belonging to the authentics owl belongs (Strigidae). It is one of the most common owls in Central Europe .

Appearance

The long-eared owl is about 36 cm long and has a wingspan of 95 cm, about the size of a tawny owl . However, it is much slimmer than the tawny owl and with a weight of 220 to 280 grams (males) or 250 to 370 grams (females) considerably lighter. Conspicuous, large feather ears characterize this species. The feather ears have no function in connection with the owl's hearing performance. Rather, the facial veil, which is noticeable in the long-eared owl, serves to enhance the hearing performance . The iris of the long-eared owl is bright orange-yellow. The face is divided by a conspicuously protruding forehead fletching. The wings are relatively narrow. The plumage of the long-eared owl is dashed black-brown and spotted on a light brown to yellow ocher background. The hand and arm wings are clearly dark transversely banded. In general, dark, rust-brown colors predominate in the females. The males, on the other hand, are somewhat lighter in their basic color. The color of the plumage is used for camouflage; resting birds in the branches can hardly be seen. The eyes are protected by an upper and a lower eyelid as well as a nictitating membrane that can cover the eye.

distribution

The distribution area of the long-eared owl covers the entire Holarctic . It stretches from Great Britain and Ireland across Eurasia including China and Mongolia to Japan and Sakhalin . The northern limit of distribution lies in the zone of the boreal coniferous forest . In Africa it occurs in the Atlas Mountains and in the mountain forests of Ethiopia . It is also native to the Azores and the Canaries . The long-eared owl also inhabits southern Canada and the northern and central parts of the United States .

Subspecies

Five subspecies are currently distinguished in the distribution area:

- Asio otus otus is the nominate form. It is based in Central Europe.

- Asio otus canariensis lives in the Canaries. This subspecies is significantly smaller.

- Asio otus wilsonianus and Asio otus tuftsi are both native to North America.

- Asio otus abyssinicus is native to East Africa. It is viewed by some authors as an independent owl species.

habitat

The long-eared owl primarily needs open terrain with low vegetation. In Central Europe it is therefore a bird of the open cultural landscape. It is mainly found in areas with a high proportion of permanent green areas and near moors . It occurs even in the high mountains if there is enough prey there.

Forests only offer the long-eared owl sufficient habitat if there is sufficient open space for hunting. The long-eared owl, on the other hand, uses the edge of the forest as a resting place during the day and as a breeding ground. She prefers conifers that offer her sufficient cover and in which there are old nests of crows and magpies . Where such forest edges are missing, it gives way to smaller groups of trees or hedges . The long-eared owl also inhabits the outskirts of cities, especially if these border areas used for agriculture.

Territorial behavior

The long-eared owl only shows territorial behavior in the vicinity of the breeding site . The immediate breeding area is characterized by chants and an impressive flight in which the long-eared owl claps its wings under its body. If there is enough food, the breeding grounds of the long-eared owls can be very close together. Eighteen breeding nests were detected on an area of 15 square kilometers in Schleswig-Holstein , which apparently offered ideal living conditions.

In winter, long- eared owls sleep together occasionally, which can contain up to 200 specimens and where the birds only keep a small individual distance. The sleeping trees visited are sometimes used for many years. In individual cases, the use of certain sleeping trees has been documented for more than a hundred years. In winter quarters it can also socialize with other species of owl, in particular the short-eared owl ( Asio flammeus ). The long-eared owl shows no aggression towards other species.

voice

During the breeding season, the male calls out a muffled and monotonous "huh" every second. This call is repeated approximately every two to eight seconds. The female responds to these calls in a similarly monotonous way with "üüiü" or "uijo". During the courtship, the female also lets out a “ chwää ” or “ chwän ” reminiscent of the begging of young owls ; a strong " chwü " or " chrööj " can be heard from the male, especially when the prey is handed over to the female .

The vocalizations also include hissing and snapping , which primarily serve to ward off enemies. The repertoire of alarm calls is very large - the alarm call that the owls utter when you get too close to the eyrie , for example, is a barking or yapping “ uäk.uäk ” and a meowing “ kjiiiiauu ”.

The branchlings of the long-eared owl, as the young owls are called, which have already left the nest but are still dependent on feeding by their parents, can make a loud beeping sound for hours during the night. It is so conspicuous that these calls are occasionally systematically registered during inventory controls of long-eared owls.

Hunting and prey

Hunting way

The long-eared owl hunts at dusk and at night. The hours of the day are only used for hunting when the prey is scarce (e.g. in winter). Before the start of the hunt, the long-eared owl cleans its plumage extensively, then hunts for two to three hours and takes a break that lasts until well after midnight. Then she hunts intensely until dawn. With this activity pattern, the owls hunt intensely for about 5 to 6 hours a day. The flight is noiseless. The search flight takes place relatively close to the ground, with the long-eared owl locating its prey optically and acoustically. If it perceives potential prey, it remains in the " shaking flight " and inspects the location where it suspects the prey.

High-seat hunting, in which the owl listens for mice from a vantage point, is also part of the hunting behavior of the long-eared owl. To hunt insects, she goes straight to the ground and picks up the invertebrates with her beak. To catch cockchafer she climbs skillfully through the branches of the trees.

Prey animals

The main prey of the long-eared owl are mice . In the Mediterranean area it is mainly real mice that are hunted by the long-eared owl. In the rest of Europe there are predominantly voles , with the field vole ( Microtus arvalis ) predominating here. Smaller songbird species are also part of the typical prey spectrum. Sparrows and greenlings are among the most common .

Reproduction

pairing

Long-eared owls become fertile towards the end of their first year of life and live monogamous in a so-called seasonal marriage . The pairs sometimes form a winter sleeping community among the birds. It is more typical, however, that the male tries to lure a female into his territory in early spring with mating calls.

At courtship , the male shows an impressive flight in which the white undersides of the wings are presented as a signal and in which the wings are occasionally clapped together under the body. This clapping of wings also shows the female in the vicinity of the potential breeding site during the parade. The mating phase and courtship also include intense shouting, as already described in the “ Voice ” paragraph . These calls sound out as alternating chants.

As with the other European owls, the male also uses soft calls to indicate the potential nesting site to the female. The long-eared owl, however, differs from the other European species by a specific sequence of movements that cannot be observed in any other species:

- The male glides to this place with its wings raised in a V-shape, lures with soft “huh” or “bu.bu.bu” syllables and turns in a stiffly bent position towards the female: the feather ears are erect (buck face ), the wings are raised above the level of the back, and ultimately "waving" up and down; at last the owl stretches in its heels in a strange hunchback position. Sometimes the horizontally raised tail feathers also tremble. The female willing to mate flies close to the male, sometimes on the same stump, crouches flat, lifts the wings limply and the tail invitingly to the horizontal. So the partners stare at each other - often at close range. The male ultimately jumps out of the "buck position" directly onto the back of the female (often turning through 180 degrees) and copulates while slowly flapping his wings…. (Mebs & Scherzinger, p. 261f)

Brood

The long-eared owl prefers to use the abandoned nests of birds of prey and crows as nesting troughs. Ground broods are also documented for the long-eared owl, but they are an exception.

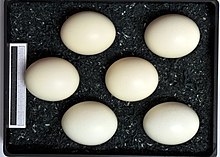

In Central Europe, long-eared owls start breeding between late March and mid-April. The female incubates from the first egg and lays an average of four to six eggs with an average laying interval of two days. If the range of prey is abundant due to a mouse gradation , the clutch can exceptionally contain up to eight eggs. During the breeding phase and during the first days of the young owls, the female only leaves the nesting trough for brief interruptions. The chicks hatch after an incubation period of 27 to 28 days and are intensely fidgeted by the female during their first days. The female cuts small pieces from the prey brought by the male and feeds them to the young owls while chuckling feeding noises. If the nestlings are older than fourteen days, the female crouches during the day on the edge of the nesting cavity or in close proximity. Both males and females take part in the defense of the brood. Only when the young owls leave the nest and crouch as branchlings in the treetops does the female take part in supplying the prey.

The boy owls

The newly hatched chicks weigh only 16 grams; However, her fine, thin down dress already reveals the feather ears that were later so conspicuous. The down dress is later replaced by a light brown dress in between, in which the young long-eared owls wear a striking, black face mask. The young owls sometimes leave the nesting trough as early as three weeks and climb into the treetops, where they remain in branches that are as little visible as possible. Young long-eared owls are skilled climbers who use claws, bills and wings to climb. After dusk, they indicate their location with a high " pull " that they repeat every few seconds. As early as 10 weeks of age, the young owls can be able to hunt mice on their own. However, the parent birds feed their offspring until they are at least 11 weeks old.

Young owls who have become self-employed sometimes travel several hundred kilometers in search of suitable new habitats. On the basis of ringing finds, it was possible to prove that migrations from Central European area to Portugal occur. The maximum occupied migration distance of young owls so far is 2,140 kilometers. However, more typical is a resettlement within a radius of 50 to 100 kilometers around the eyrie.

Predators and enemy behavior

The relatively small long-eared owl is one of the prey animals of the eagle owl . Larger birds of prey also hunt long-eared owls from time to time. In particular, the females that breed in the open eyries are often preyed on by the common buzzard . Also marten can be dangerous, especially the young, not yet able to fly chicks.

Long- eared owls try to avoid the threat posed by predators mainly by camouflaging them, which is provided by their plumage. The breeding females, who are particularly endangered, crouch deep in their nesting troughs. Long-eared owls also have a repertoire of threatening gestures. Similar to an eagle owl in a hopeless situation, the long-eared owl also fans out its wings to form a wing wheel, thereby visually enlarging its appearance. At the same time it hisses loudly and tightens its beak. The young branchlings already master this behavior. In acute danger, they usually climb into higher areas of the trees. If they are followed up until then, they may even jump to the ground.

People and predators who get too close to the eyrie are occasionally distracted by what is known as enticing. Here, the owl fakes the attacker with a restricted ability to move by letting its wings droop. This temptation goes so far that it lets itself tumble down from a branch with loud alarm calls to distract the potential attacker from the nest.

Migratory behavior

Asio otus is usually a partial migrant : Long-eared owls, which normally live in the northeastern distribution area of the European continent, migrate to the southwest during the winter half-year. In order to better survive the winter, the birds prefer to stay in the vicinity of larger cities and towns. There is still enough food here, even in the cold season. Long-eared owls, which live in climatically favorable regions, do not leave their ancestral area in winter.

Life expectancy

Of the young owls of a year, only every second survive their first year of life. In the wild, a maximum age of 28 years has been proven based on ringing finds.

Inventory development

The population of long-eared owls is mainly dependent on the number of mice. If the mice have only low growth rates, there are considerable fluctuations in the long-eared owl population. In 2003 the IUCN estimated the total population at around 120,000 animals. Extrapolations based on recent European figures now amount to 1.5 to 5 million copies. For Austria and Switzerland it is estimated that around 2500 to 3000 breeding pairs have their habitat there, for Germany the number of breeding pairs is estimated at around 32,000.

Declines in stocks are due in particular to the more intensive use of agricultural land. Similar to other Central European owl species, the most important protective measure is the preservation of structurally rich, natural landscapes.

Overall, the long-eared owl is classified by the IUCN as “not endangered” (“least concern”).

The question of whether the long-eared owl can be displaced by the tawny owl in some of its habitats has not yet been adequately investigated. Research in the Netherlands shows that the long-eared owl population declines as the number of tawny owls in the area increases. The competition for food and breeding grounds certainly also play a role here.

photos

literature

- Jürgen Nicolai : Birds of prey compass. Identify birds of prey and owls safely. Gräfe and Unzer, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-7742-3805-7

- Theodor Mebs , Wolfgang Scherzinger : The owls of Europe. Biology, characteristics, stocks. Kosmos, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-440-07069-7 (comprehensively reproduces the way of life of the thirteen owls represented in Europe)

- John A. Burton (Ed.): Owls of the World. Development, physique, way of life. Neumann-Neudamm, Melsungen 1986, ISBN 3-7888-0495-5

- Wolfgang Epple: Owls. The mysterious birds of the night. Gräfe and Unzer, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-7742-1790-4 (compared to the book by Mebs and Scherzinger, this is more the book for "owl beginners" - it is deliberately written so simply that it is also suitable for children and young people )

Web links

- German Working Group for the Protection of Owls (AG Eulen)

- Long-eared Owl on owlpages.com (English)

- Eulenwelt.de

- State association of owl protection in Schleswig-Holstein

- Asio otus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on 13 May, 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Asio otus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 5.6 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (Eng.)

- Long-eared Owl feathers