Common Swift

| Common Swift | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Common Swift ( Apus apus ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Apus apus | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) | ||||||||||

| Subspecies | ||||||||||

|

The common swift ( Apus apus ) is a species of bird in the sailor family . It resembles the swallows , but is not closely related to them; the similarities are based on convergent evolution . The common swift is a long-distance migrant . It stays mainly from the beginning of May to the beginning of August during the breeding season in Central Europe . Its winter quarters are in Africa , especially south of the equator.

Common swifts are extremely adapted to life in the air. Outside of the breeding season, they stay in the air for about ten months with almost no interruption. In midsummer the sociable birds are very noticeable in the air above the cities with their shrill calls. During their flight maneuvers they can dive at speeds of more than 200 km / h.

The common swift is the only type of sailor that is widespread in Central Europe. In the German-speaking area there are numerous regional names for the bird, "Spyre" or similar names are very common, for example in Switzerland or Tyrol.

Appearance and characteristics

The shape is similar to a swallow, but the swift is slightly larger than the European swallows. The wings are long compared to the body, and their sickle shape is easy to see when gliding . The tail is relatively short and forked. Outwardly, males and females cannot be distinguished. The plumage is sooty to brownish-black with the exception of the gray-white throat spot, which is difficult to see in flight. Seen from the front, the face appears rounded; the eyes are relatively large and the iris is deep brown. The small, black beak is bent slightly downwards. The short feet are blackish flesh-colored. The four toes end in sharp claws; as with all sailors, they are all directed forward.

Adult swifts weigh an average of around 40 grams, but their weight varies a lot with their nutritional status. Non-breeding birds and common swifts that have just arrived at the nesting site are usually somewhat heavier than breeding birds. The trunk length averages 17 centimeters, when the wings are put on they cross and protrude over the tail by about four centimeters. The wingspan is between 40 and 44 centimeters. The wings of the hand are greatly elongated in comparison to other bird species; The upper and lower arms are short and compact.

The juvenile plumage is darker and less shiny, the white of the throat is wider and purer than that of adult birds. In addition, young birds differ from adult birds by their white feather fringes, which are most noticeable on the axillary feathers, the wing covers, the large plumage and especially on the forehead. Only the hems of the forehead feathers are preserved until the juvenile moult, while the other white hems soon disappear due to wear and tear. Annuals look like adult common swifts; they can best be recognized by their worn-out juvenile large plumage, with the ends of the tail feathers in particular being more rounded.

Mauser

The juvenile moult takes place in the African winter quarters and is a partial moult, whereby the wing feathers and part of the central tail feathers are retained. The ten wings of the hand , which form the main supporting surface of the wing, will be changed for the first time during the next moult and have already made two trips to Africa.

The annual moult of adult birds is a full moult and can start changing the small plumage as early as July. The moulting of the wings begins in mid-August or early September and continues gradually and synchronously on both sides over 6 to 7 months, so that the ability to fly is always guaranteed. Finally, the 10th hand swing fails with a normal moulting sequence.

flight

The swift's physique enables a fast, agile gliding flight in which the wings are stretched almost horizontally and are only slightly bent downwards. Common swifts can also sail in strong thermals , but normally flapping and gliding phases alternate with different lengths. It is also characterized by frequent tilting around the longitudinal axis, which is interspersed in places during gliding phases. In conjunction with the typical twists and turns, this can give the impression that the flapping of the wings is asynchronous. Swifts keep their heads horizontal, even on tight flight curves, so that they can always fully perceive their surroundings with a constant orientation. In order to avoid greater loss of altitude, flapping phases are interspersed during the gliding flight, which can last from 0.5 to 22 seconds, the average duration is around 4 seconds. The beat frequency is usually between 7 and 8 beats per second. While gliding usually 20 to 50 km / h are, in powered flight reached h 40 to 100 km / in flight games are more than 200 km / h. Animals that spend the night in the air fly at an average of 23 km / h. The best relationship between energy expenditure and distance traveled is for migrating birds at an average speed of around 32 km / h.

Common swifts adapt the shape of the wings to the flight conditions. Fully extended wings allow the best slow gliding flight and up to 60 percent more distance than in the basic position. Retracted wings are used for flight at high speed and fast turns; if the wings were in a different position , they would otherwise not be able to withstand the wind pressure.

voice

Common swifts are particularly fond of shouting in company and fighting. Most striking is the high-pitched, high-pitched "srieh srieh", which the birds can use to drown out traffic noise in cities. In addition, swifts utter a few other monosyllabic or two-syllable calls such as "sprieh" or "sriiü". The calls are stretched differently, sometimes higher or two-syllable. Birds chasing each other give off an individual "sirrr" or a staccato-like "sisisisi" that is different in height and length . The frequency of their calls is between 4000 and 7000 Hertz , in a high frequency range that is easily perceptible to the human ear.

The so-called “dueting” at the breeding site is also of particular importance. A swift pair there shouts “swii-rii” together; the lighter “swii” comes from the female and the slightly deeper “rii” from the male. This behavior is the best way to differentiate between the sexes. In addition, this duet has an even more important function for the birds themselves, because it serves an efficient method of dividing the often scarce, suitable nesting niches. So-called “banging” has long been known in this context, in which individual birds briefly touch the entrances to possible nesting sites and thus make themselves noticeable. Often the birds pause only briefly, only to fly on again without inspecting the nest cavity. If a single bird is already occupying the inside, usually dark, breeding cave, it will be noticeable through its gender-specific reputation, and the approaching bird will quickly find out whether it is a potential candidate for starting a family.

Differentiation between swifts and swallows

In Central Europe, barn swallows and house martins in particular hunt for insects in the air in a similar manner to the somewhat larger common swift, sometimes mixed groups occur. The best criteria to distinguish the different types are as follows:

- The high-pitched screams of the common swift are clearly different from the rather inconspicuous "chatter" of the swallows.

- The swift's narrow, sickle-shaped wings are longer than its slender body, and the flight silhouette resembles the shape of an anchor.

- Common swifts alternate between fast, deep wing beats and longer gliding phases. The flight of the swallows, on the other hand, appears fluttering and prancing, and they flap their wings a little backwards.

- The underside of the common swift is shiny black-brown, except for the barely visible throat patch. Swallows, on the other hand, have a beige-white underside, barn swallows also have a reddish throat color that can be seen from below. In addition, barn swallows are easy to distinguish by their long, deeply forked tail skewers.

Confusingly Related Species

Within the family of sailors , the breeding areas of swifts and alpine swifts overlap most widely, but the alpine swift is considerably larger and very well characterized by the white throat and belly side. It is much more difficult to distinguish from the pale swift of the same size in the Mediterranean area and in the Middle East , where the breeding areas overlap and the birds often hunt insects together. In comparison, the common swift appears “sleek”, the body is slimmer, the wing tips are more pointed and the tail is forked a little deeper. The plumage of the pale swift is a little lighter and more olive-brown compared to the black-brown of the common swift. The greatest risk of confusion between the darkest subspecies of Fahl glider ( A. pallidus illyricus ) and compared to nominate lighter something subspecies A. a. pekinensis of the common swift, which meet each other on the train and in winter quarters.

Especially during the displacement and Heimzugs also provides the on Madeira and the Canary Islands occurring Plain Swift confusion possibility is also there in the African winter quarters with mouse sailors , Schouteden sailors , African Black Swift , Forbes-Watson's Swift , Bradfield's Swift and Nyanza Swift a number of African sailors species not are always easy to distinguish from common swifts.

Distribution, habitat and migrations

distribution

The breeding area extends over large parts of the Palearctic region . On the islands of the Mediterranean and in Europe, the swift breeds everywhere except in the northernmost areas - Iceland , northern Scandinavia and the tundras of Russia . It is also absent in the northernmost part of Scotland , on the Faroe Islands , in the southern mountain regions of Scandinavia and parts of the Alps and the Balkans . In the very north-west of Africa the swift breeds near the Mediterranean coast and, according to some reports, various Canary Islands have recently been colonized and now mark the southwestern end point of the breeding area. In the Middle East , swifts are found in Asia Minor , on the Mediterranean coast and occasionally in Syria as a breeding bird. In Asia, the breeding area extends to the 60th parallel in the north. The eastern border of the area is formed by the Oljokma River in Siberia , the Great Chingan in northeast Inner Mongolia and the Chinese provinces of Liaoning and Shandong . The southern border of the Asian breeding area runs roughly along the 35th parallel, but the swift is missing in the Central Asian steppe belt.

During the winter in the northern hemisphere, swifts “summer” between equatorial and South Africa , from the northern border of the tropical lowland rainforests and the equator in East Africa to the southern edge of the Orange River basin in South Africa.

habitat

In Central Europe, swifts breed mainly on multi-storey stone buildings, including residential houses, church towers, factory buildings and train stations. A variety of cavities under roofs and eaves are used in such buildings , for example roller shutter boxes or crooked tiles. New buildings with a smooth facade are rarely used. Due to the availability of suitable breeding opportunities, swifts often only settle in a few places, for example in town centers, industrial or port facilities, in small towns often exclusively at churches or other historical buildings.

The common swift was originally mainly rock breeder, today these are rare in Central Europe and only known from a few regions, such as the Elbe Sandstone Mountains . It is believed that the transition from rock to building breeder took place in the Middle Ages ; castles built into the rock may have been the link through which birds approached human structures and became their cultural followers .

The common swift is also tree-breeder, but only sporadically in Central Europe; in Germany, for example, this only applies to one percent of breeding pairs. Some of these can be found in the Harz Mountains , where the ecological relationships have been well researched. Such “tree swifts” need trees that are over 100 years old in order to be able to develop abandoned woodpecker caves into sailor caves. In the north of Fennos Scandinavia and in some areas of Russia the swift avoids localities and lives in the surrounding forests.

Both in the breeding area and in the winter quarters, the common swift occurs at all altitudes where the climatic conditions guarantee a sufficient supply of insects. The highest breeding places are found in the distribution area of the subspecies A. a. pekinensis between 1,500 and 3,300 meters, such birds were observed looking for food at more than 4,000 meters, the highest migratory birds observed were at an altitude of 5,700 meters near Ladakh .

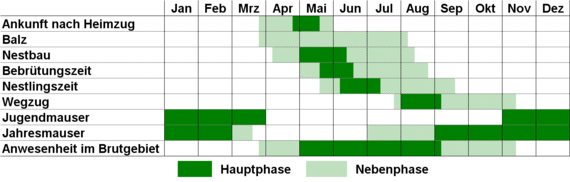

hikes

Common swifts spend no more than 3 to 3½ months in the breeding area as well as in the South African winter quarters, the rest of the year is required to move away and home. They move out shortly after the young birds leave, in Central Europe mostly in the second half of July or the beginning of August. Unsuccessful breeding birds, young birds and the not yet sexually mature annuals usually migrate first, then mated males and finally the breeding partners. The longer stay of the females at the breeding site serves to rebuild the fat reserves. The time of departure is apparently determined photoperiodically and begins when the day length falls below about 17 hours including twilight phases. This is why birds that breed further north break out later, for example in Finland in the second half of August. These stragglers are then literally "chased" through Central Europe by the rapidly decreasing day length and therefore hardly noticed in the field ornithologically .

The predominant migratory direction from Central Europe is southwest to south, the Alps do not form a barrier. Especially when the weather is bad, swifts follow rivers where better food can be found. The western and central European populations mainly migrate over the Iberian Peninsula and northwest Africa. Birds from Southeastern Europe and Russia are mainly involved in the considerable migration in the eastern Mediterranean , the location of the migratory divide and the mixed area is unclear. Most of the westerly moving sailors follow the north-west African Atlantic coast, in some cases the Sahara is also flown directly over. Once in the humid savannas of Africa, the migration direction seems to change to the southeast until the main wintering areas are reached.

During the “oversummer” in Africa, a large number of swifts are evidently following the Inertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), which follows the area of the highest sun with a one-month delay. In the arid regions there, this seasonal precipitation temporarily creates a rich supply of insects, which the swifts, which are almost continuously in the air during this time, use consistently.

Some swifts, probably part of the annual birds, remain in Africa. The majority of the migrating birds now migrate northwards through Africa, with the direction of migration being somewhat more easterly than when they were leaving. When migrating home, the birds prefer to move to the front of low pressure areas in order to take advantage of the south-westerly current in the warm sector of the low pressure . In contrast, they take advantage of the northeast winds on the back of a low as they migrate.

Swifts in Central Europe mainly arrive in the second half of April and in the first third of May, in lowlands and near waters rather than in higher altitudes. The birds also arrive later in northern areas. The weather during the train has a great influence on the duration of the train, so that the time of arrival can vary locally by around three weeks.

Weather evasion

Swifts encounter rainy weather with so-called cyclonic weather flights. When approaching a low pressure area , also known as a cyclone, many swifts move in front of its weather fronts. In many cases they already start when the cold front is still 500 to 600 km away. The birds quickly form flocks, which first move to the warm sector of the low, where they can still find enough food even when it rains. Later they fly against the wind through the cold front of the low pressure area and are thus exposed to the heaviest rainfall for the shortest possible time. Most swifts walk around the center of the depression in a clockwise direction and often only return to their starting point after 1,000 to 2,000 kilometers. However, individuals from different regions regularly mix temporarily due to such weather evasions .

The non-breeding birds, especially the annuals, take part in the weather flights. But also the breeding birds often take part in the evacuation. The young birds usually survive the absence of their parents in a kind of starvation sleep (see starvation ).

Food and subsistence

Common swifts, as aerial hunters, feed exclusively on insects and spiders . The regional frequency of certain prey in the airspace and the food spectrum of the birds there largely match, so that it can be assumed that swifts are not picky and use all accessible objects of suitable size. In Europe, over 500 species have been identified as prey, although a significantly higher number can be assumed, as the previous investigations have been limited to very few locations. The main prey are probably aphids , hymenoptera , beetles and two-winged animals , often flying ants and termites also play an important role in Africa . If there is an option, prey animals with a body length of more than 5 millimeters are preferred, the housemother , an owl butterfly with a body length of 26 to 29 millimeters , is one of the largest animals proven to be prey .

The acquisition of food takes place almost exclusively in the air, reading of food on gutters, canopies or the like is rare. Depending on the weather and the distribution of the supply, swifts hunt in changing areas and altitudes, often at a short distance from the vegetation at low temperatures. Normally the flight altitude is between 6 and 50 meters, but on warm days it is often over 100 meters above the ground. Common swifts also follow their prey when it is washed up in the rising thermals. So they hunt at heights up to the cloud base of cumulus clouds. In Central Europe these are heights of up to around 3,000 m. Glider pilots use swarms of swifts hunting as thermal indicators: Where swifts are at higher altitudes, there is a high probability that ascending air currents can be found. The greatest hunting success is likely to result in calm and warm weather. The search for food takes place alternately between flapping and gliding flight with rapid changes of direction; the beak is only opened when it is snapped shut. However, common swifts do not achieve the extreme agility of swallows , which also target larger insects than common swifts. The aerial hunt of the swallows is considered to be much more effective. Birds flying apart from each other keep optical contact when searching for food, so that when swarming ants ascend, hundreds of swifts can often be found within a few minutes.

The nestling food does not differ significantly from the other prey spectrum of adult birds, it consists almost exclusively of objects 2 to 10 millimeters in length. Breeding birds collect the food in the throat pouch until a defined amount is collected, which can be done in just 40 minutes in good weather, but takes considerably longer in bad weather. In good conditions, a feeding breeding pair can produce 50 grams of food in one day, which is equivalent to more than 20,000 insects or arachnids.

Drinking takes place in a fast, straight gliding flight, with the body forming an angle of about 20 to 35 degrees to the surface of the water. The wings are held in the V position. The beak plunges for a distance of about half a meter and almost simultaneously with the opening of the beak the tail feathers are pushed downwards.

Starvation

Older, feathered nestlings can survive the lack of food caused by bad weather periods and weather flight of the adult birds by becoming torpid . All body functions are reduced to a minimum, heartbeat and breathing slow down. The body temperature drops after a while at night from the normal value of around 39 ° C to just above the ambient temperature. First, the fat reserves are used up, and finally body tissue is attacked, especially the muscles or the liver . In this way the nestlings can survive without food for one to two weeks. When the body temperature falls below 20 ° C, death usually occurs.

Adult birds can also become torpid to a limited extent, but can only survive three to four days without food. If the animals do not get to areas with better conditions when the weather is evacuated, they will cluster tightly and motionless on walls and rock faces. The swifts can hardly be observed in this state, as they retreat into sheltered niches, because otherwise they would be helplessly at the mercy of enemies due to greatly reduced reflexes .

Reproduction and Life Expectancy

Common swifts reach sexual maturity at the end of their second year of life at the earliest , so the one-year-old birds spend the first season in the breeding area after returning from Africa without reproducing. In some cases, however, potential breeding caves are already being inspected and occupied. Adult swifts lead a monogamous marriage for at least one season, but usually for many years. The partnership-based loyalty is based on a pronounced nesting site bond. The partners do not arrive in the breeding area together, but usually about 10 days apart.

The only three-month breeding period allows only one annual brood, but replacement broods are often found in the event of clutch loss, mostly in the same nest. The breeding success is strongly dependent on the weather. Because of the common swift's high life expectancy, even years without offspring hardly affect the population.

Nest location and nest

Common swifts, which breed socially in colonies, prefer nest locations in dark, mostly horizontal cavities with the possibility of direct approach. The cave entrances, which are usually 6 to 30 meters high, are approached by means of a so-called underfly landing , in which a considerable part of the swing is slowed down by a short climb before landing. The nest is usually in the rear corner of the cave, as far as possible from the entrance. If necessary, tubes with a diameter of at least 10 centimeters and a length of up to 70 centimeters can be negotiated between the cave entrance and the nest. In contrast to the Alpine Swift , where several pairs can share an entrance, each pair of swifts usually requires a separate entrance.

The nest is built by both partners and can start one day after mating . The collection of nesting material takes place in flight, with occasional interruptions due to the wind dependency. The objects that are not allowed to offer too much aerodynamic resistance are usually transported in the beak, less often in the throat pouch or with the feet. Depending on the offer, stalks, leaves, scales of buds, seeds, fibers, hair, feathers, and scraps of textile and paper are used. The nest forms a messy, shallow bowl with a central depression that is coated with sticky, rapidly hardening saliva . Often times, a nest is used for many breeding periods one after the other and is only supplemented and re-salivated every year, whereby the diameter can grow from 9 centimeters to 15 centimeters when new. Found structures of other cave breeders such as starlings , house sparrows or black redstart are occasionally forcibly taken over and built over, sometimes with eggs or young birds. Overbuilt nests sometimes cause considerable stench, which obviously does not bother the swifts.

Courtship and mating

When the weather is good, the flight balz begins immediately after arrival in the breeding area, but can also begin in the winter quarters from the beginning of November. During courtship flight, two sailors pursue each other at a distance of one to ten meters, the pursuer is probably the male who tries to attack the female with a typical V-position of the wings. This courtship fly has an animating effect, so that other birds join in or open the hunt for another bird. Often such a collective parade goes over to foraging for food quite suddenly.

Sometimes pairs are formed at the nesting site, and in particular previous partners often come together in the nest cavity. The intruder is received by the cave owner with loud screams and violent threatening gestures. The very excited animals stand up several times, which can be interpreted as a gesture of appeasement, the situation only slowly relaxes and mutual feathers care follows. If the newcomer is the partner from the previous year, the threatening gestures are weaker and the transition to mutual cleaning is much faster.

Copulations occur both in the brood cavity and in the air. When joining at the nesting site, the male holds onto the neck with its beak and its feet in the plumage of its quiet partner. While the female lifts its tail, the male winds its abdomen downwards. Usually three to four copulations follow one another. The flight copulations, which apparently only take place in good weather, begin at a height of about 80 meters and are reminiscent of the Flugbalz. The female, which initially flies straight ahead, begins to vibrate with her wings and loses speed. The following male increases his speed, hovers diagonally from above on the partner and digs into the back plumage. The wings remain calm during mating. During copulation, the couple loses height and speed and normally separates again after two to four seconds.

The evolutionary significance of such copulations “on the wing” is difficult to explain, since it has been proven that copulations also occur in the breeding cave and the question arises as to what reason it could be that the birds expose themselves to such a risk. But the flight copulations are proven by numerous scientific sources, including other types of sailors. The assumption that flight copulation could represent a possibility of sexual selection for the female is not tenable, since the frequency of non-partnership paternity in swifts seems to be extremely low even for a “normal” colony breeder.

Clutch and brood

The eggs are elongated elliptical, but unevenly. They measure 25 × 16 millimeters, the shell is white and dull, the gray spots come from the droppings of the sailor louse fly . In more than 90 percent of the cases the clutch consists of 2 to 3 eggs, occasionally only one egg and very rarely 4 eggs. In Central Europe, eggs are usually laid in the second half of May, usually during the morning.

Both the clutch size and the incubation period, which lasts an average of 19 days, are heavily dependent on the weather; the incubation period can be between 18 and 27 days. Such temporal variability and length is a peculiarity in a bird of this size. The partners alternate during incubation and apparently hatch in approximately equal proportions, the eggs are resistant to cooling when the weather is not enough.

Development of the young

Siblings usually hatch within two days, they are blind and completely naked. The fledging period as the incubation period strongly dependent on weather conditions and may be 38 to 56 days, usually there are just over 40 days. In the first 2 to 7 days hudern the adult birds almost constantly, later in favorable weather only at night. The parents collect the food in the throat sac and use saliva to shape it into a hazelnut-sized ball in which many small animals are still alive. Only in the first few days is the bale distributed in portions to the nestlings, later handed over as a whole to the young, who call and swing their bills. Fresh excrement is initially swallowed by the adult birds, later carried away in the throat pouch.

After 2 to 3 weeks, the young jump around in the brood niche, fluttering, initially resting again after a few seconds. At around one month old, they lift their bodies up with outstretched wings so that their feet lift off; they can hold this position for 10 or more seconds before flying out. Nestlings also perform typical flight movements at night.

Under optimal conditions, nestlings, which weigh about three grams when hatched, can reach their maximum weight of up to 60 grams in less than three weeks; they then weigh one and a half times that of an adult bird. Only a few days before they fledge do they stop begging and lose weight to the optimal flight weight of around 40 grams. Studies have shown that even additional weights glued to the back or clipped wing tips do not impair the ability of the young birds to optimally adjust their weight to the day of the flight. It is assumed that the "push-ups" described above also enable the relationship between body weight and wing area to be determined in this context.

On the day of the flight, the nestlings spend most of the day at the entrance hole. Often hours go by in which the bird keeps sticking its head out with its wings spread and tail spread out. The parents are not present when they fly out, in the case of late broods they may already be on their way to winter quarters. Presumably to protect them from predators , they usually fly out in the evening hours. The young birds are immediately independent and spend the first night in the air, as has been proven with telemetry transmitters.

Life expectancy

Common swifts have a high life expectancy and an unusual age structure among birds, in which older age is still well represented. The average annual death rate of adult birds is estimated at 20 percent. The mean life expectancy of adult birds is between 4.3 and 6.2 years, for fledgling young birds it is around 2.4 years. An age of 10 and more years is not uncommon, some times an age of more than 20 years has been proven by ringing .

The direct or indirect influence of weather on life expectancy is significant. In persistent wet and cold weather with temperatures during the day below 10 to 12 degrees, the existence of entire populations is threatened if such a weather situation is also extensive or further evacuation is prevented by barriers. Such mass extinction of adults can permanently decimate a population, whereas a one-year breeding failure can normally be compensated for in subsequent years.

Enemies and parasites

Enemies

The natural enemies of the common swift in Central Europe are mainly tree falcons and peregrine falcons , which often prey on common swifts in open air. For some other bird of prey species such as kestrel and sparrowhawk, as well as for owls, common swifts tend to be a rarer occasional prey , especially if the animals are weakened due to a lack of food due to persistent wet and cold weather. When the weather is bad, domestic cats can also sometimes manage to capture the birds that fly low. Beech marten and weasel pose an occasional threat in the breeding cave .

Parasites

Particularly noteworthy is the crataerina pallida ( Crataerina pallida ), a specialized in this type parasite . The life cycle of the louse flies is synchronized with that of the sailors, the larvae deposited in the nesting cave hatch with the bird nests. The 6 to 10 millimeter large parasites, which prefer to suck blood on the neck and abdomen, can weaken young birds. It is not known whether this affects the swift mortality rate. Up to 12 louse flies can be found in the plumage of a nestling; an adult bird can have up to 20. The parasites are apparently only removed, but not eaten, if they can be reached. Common swift flyers can no longer actively fly themselves, they can only sail.

In addition to louse flies, other parasites such as tapeworms , mites , bed bugs and lice are also found. Their impact on mortality and life expectancy is unclear.

behavior

Activity during the breeding season

The beginning of the activity is strongly dependent on the weather. The nächtigenden in the nest nesting birds leave this 50th June at the middle of passing through Germany Latitude average of 15 minutes before sunrise; at the 60th parallel that runs through southern Finland , however, one hour before sunrise due to the longer twilight . When it is cloudy, strong winds and low temperatures, the birds often take to the air much later and only when it is much brighter; when the weather is very bad, they do not go on excursions or only undertake irregular, sporadic excursions. The end of activity, on the other hand, is far less influenced by the weather and is, for example, at the 50th parallel in June in clear weather about half an hour after sunset. To make better use of daylight, foraging flights also take place over hills, while the breeding sites in the valleys are still or already in the dark.

Climbing flights during twilight

Common swifts often climb to altitudes of 2000 to 3000 m within about half an hour during the evening twilight . Since the birds also undertake such a climb at dawn, the long-cherished assumption that this climb was related to the overnight stay in the air is no longer tenable. Swifts reach their greatest height during nautical twilight, both in the evening and in the morning . The altitude reached seems to be related to the air temperature, but not to the cloud base, the humidity or the presence of insects. In the evening, the descent that follows the ascent takes about twice as long as the ascent, in the morning it is exactly the other way round, there the rate of climb is only about half the rate of descent. The birds show the same behavior pattern during the air-bound way of life in the African winter roost.

It is assumed that these climbs could be two reasons: Firstly, could be that the Swifts doing their magnetic sense to calibrate because during twilight are polarization pattern clearly visible and already see the stars, in addition, the high altitude allows a good view of the landscape and an undisturbed perception of the earth's magnetic field. On the other hand, the swifts could gain an overview of the weather and the conditions in the atmosphere, such as wind strength and direction as well as temperature at different heights, by climbing.

Overnight in the air

As early as the 18th century, Lazzaro Spallanzani suspected that common swifts slept in the air, as he could often watch them in the evening as they spiraled higher and higher. Although this conclusion is probably not true, as the evening climb seems to have other reasons (see previous section), it has meanwhile been proven that common swifts, especially non-breeding birds, often spend the night in the air. The sailors spend the night at altitudes between 400 and 3600 meters. individually or in flocks and are mostly mute.

At the beginning of the night a phase with reduced wing flapping can be observed when the birds gradually lose altitude again after the evening climb in gliding flight. For the rest of the night, the glide phases seem shorter than during the day, which could be due to the lower thermals . However, this observation contradicts the observed behavior of the alpine sailor , in which the gliding phases seem to be longer at night.

Apparently the birds try to remain stationary as possible and fly comparatively slowly against the wind, so that in stronger winds they are even driven backwards and have to fly back in the morning to get back to the starting point. It is unclear how swifts recover at night as the miniaturization of the telemetry equipment required for research is not yet sufficient to be used for birds of this size. One suspects a kind of half-brain sleep , similar to that known from other animal species.

There is much speculation and discussion about the evolutionary advantages of staying overnight in the air. Even for a bird that has adapted so well to life in the air, spending the night in flight represents a considerable amount of additional energy expenditure compared to spending the night on the ground. What is certain is that the birds do not stay in the air for night-time insect hunting because they cannot see sufficiently can. An attempt to explain it assumes as a starting point a lack of suitable sleeping accommodations, especially in African winter quarters, where suitable nesting and sleeping places are already being used by 20 other native sailor species that breed there. According to this theory, the common swift has made a virtue out of necessity in the figurative sense, because by foregoing ground-based sleeping facilities, it is possible for it to consistently follow the shifting largest food supply in the intra-tropical convergence zone (see also hiking ).

Non-breeding season air-bound way of life

Outside the breeding season, swifts are in the air for more than 99% of the time for 10 months. In Africa south of the Sahara, where the birds stay during the northern hemisphere winter months, no sleeping or resting places are known. In order to research the behavior of common swifts outside of the breeding season, some birds breeding in southern Sweden were fitted with motion sensors and data loggers between 2013 and 2014 . In a total of 13 individuals, an evaluation of the data was possible after recapture, in 5 of them for both years. For a common swift, only an inactive phase of two hours was registered for 314 days. A few other birds like this one were in the air practically non-stop, although some were also noted repetitive nocturnal rest periods that rarely lasted longer than two hours. Since some individuals managed practically without flight breaks and there were only a few rest breaks lasting all night, it can be assumed that such breaks are physiologically unnecessary for swifts and that the few recorded breaks may be due to bad weather.

Social behavior

Common swifts are gregarious all year round and during the breeding season usually live in colonies where many activities are synchronized. Particularly noticeable are the social flight games, the so-called "screaming parties", which can only be seen in the evenings when the weather is good and are accompanied by loud calls. The birds form a more or less closed flock that occasionally circles at great heights and repeatedly flies past the nesting sites at breakneck speed. All birds of the colony take part, including the breeding birds and, in late summer, the fledgling young. Very complex flight maneuvers can be seen in these flying games, some of which are reminiscent of courtship flights. The “Screaming Parties” are often immediately followed by the evening climb. The flight games are particularly intense shortly before they leave; possibly they are used for social synchronization.

Movement on the ground

One aspect of the extreme adaptation of the common swift to the airspace are also the small feet, which are not particularly suitable for landings and locomotion on the ground. On the ground he stands on his claws and heel joints; With its head slightly bowed and its slightly spread feet sweeping out, the common swift can walk like a lizard , which makes a rather awkward impression. By means of the four claws pointing forward, adult birds can climb very well. Swifts can hang from branches or poles, but not sit on them.

Even if swifts avoid landing on flat ground as far as possible, healthy animals can, contrary to claims to the contrary, easily take off from the ground, provided there is sufficient free space for take-off. The bird can catapult itself up 30 to 50 centimeters from the ground with its feet or jump into the air after jumping 3 to 5 steps. Although the tips of the hand wings touch the ground during such a take-off, the common swift never pushes itself off the ground with its wings. Weakened animals in particular also climb walls and trees in order to drop into the air from there.

Comfort behavior

To care for the feathers, the chest and shoulders as well as the wing covers are worked in flight with the beak up to the middle of the hand, if necessary the wing concerned is put on briefly. The cleaning of the parts of the feathers that cannot be reached with the beak and the arranging of the flight feathers is done by quickly, alternating forward and backward pulling of the wings along the flanks. The so-called “flutter fall”, in which the bird flaps its wings downward, is apparently a reaction to disturbing stimuli in the plumage, and it probably also serves to shake off louse flies . Animals sitting in the cave spend most of their time cleaning. Thanks to the enormous rotation of the head, all areas of the body can be reached. Really all parts of the plumage - with the exception of the head, neck and neck, of course - can only be reached by swifts hanging.

Aggression and enemy behavior

Swifts behave very aggressively towards unknown conspecifics in the breeding cave. The cave owner moves menacingly towards the intruder with extended and raised wings and also displays his feet as "weapons" by lifting the facing wing and tilting his body sideways. If the invading bird reacts with the same behavior, the birds fight with each other, clinging to each other with flapping wings and beaking. Such violent arguments, accompanied by loud shouts, often last more than 20 minutes, sometimes even 2 to 5 hours, including occasional interruptions. Eggs and young birds can also fall out of the nest. The arguments with alien nesting site competitors such as star or house sparrow are similar to intraspecific arguments, only in this case the opponent is often injured or killed.

When a tree falcon and other larger birds of prey appear , swifts form a flock, often together with swallows . They then circling collectively above and behind the attacker and spiraling up like him. Occasionally, fake attacks are likely to take place. If the enemy moves away, they will be pursued for a while. Under normal conditions, birds of prey are only able to capture a swift from the flock in exceptional cases.

Inventory and inventory development

Although the common swift is not currently threatened, the species was voted bird of the year in Germany and Austria in 2003, and in Switzerland in 2005. The common swift was intended to draw attention to the problems of its habitat as a popular figure , also representative of other building-breeding species.

The European population is estimated at 4.0 to 4.9 million birds, the global population is said to consist of about 25 million individuals. These population figures are only rough estimates, however, as they are mostly derived from the maximum number of flying individuals in the individual areas and reliable information is hardly available for larger areas. This is also evidenced by the fact that the numbers published by BirdLife International for the European population are more than three times as high as those mentioned above, which were published in 1997 by Boano and Delov.

Although no exact figures are available, an increase in the population can be assumed in the 20th century because the common swift profited from urbanization and the architectural styles prevailing at the time. However, today's buildings and modernized facades offer far fewer niches than older buildings that are suitable for breeding grounds. The swift's loyalty to the breeding site may have an additional disadvantage here, as sailors returning from their winter quarters are often "at the closed door" after modernization. In recent years, despite the climatic development that is actually favorable for the common swift, a slight decline in the population appears to have emerged in Central Europe. Another observed effect is the disappearance from the centers of large cities like London . Here it is assumed that the cause is not the air pollution, but the increasing distance to the open spaces and waters of the surrounding area.

At Lake Constance and in Vorarlberg, a significantly lower incidence of swifts was observed in mid-May 2018 than in the 8 years before.

Systematics

Of the more than 90 species of sailors worldwide, the common swift is the only one that is widespread in Central Europe. Most of the other types of sailors are native to the tropical regions.

Two subspecies are distinguished for the common swift : In addition to the nominate form Apus apus apus , this is Apus apus pekinensis . The latter differs from the nominate form primarily in that its plumage is more brown, the wings and especially the arm wings also appear gray-brown. The forehead is brownish-gray and clearly set off from the rest of the upper side, the white of the throat is clearer and more extensive. A. a. pekinensis colonizes the eastern parts of the range starting from Iran , the winter quarters are in and around the Kalahari desert.

Swifts and humans

Etymology and naming

The name "common swift" comes from the birds' behavior to sail along or near walls. In English, sailors are called Swifts ; the adjective swift means something like “nimble” or “hurried” and goes very well with the sailors' way of flying. In the vernacular they are in Germany "Spirschwalbe" in Middle High German, as in Switzerland , in Alsace or in Tyrol called "Spire" or "Spyr". Etymologists disagree as to whether this designation means the long, pointed wings of the birds or the preferred inhabited spire. Still others interpret it onomatopoeically based on the characteristic loud calls. From many other common regional names such as "Turmschwalbe", "Mauerschwalbe", "Kirchschwalbe" or "Quieckschwalbe" it becomes clear that swifts were once attributed to swallows. In the Romansh-speaking area of the Surselva there is the viewing platform Il spir , which is named after the local Romansh name of the common swift . In the Engadine , Romansh is closer to Italian, which is why the name Radurel Pitschen is closer to the Italian name.

In the Naturalis historia the sailors are called Apoda . This and also the scientific name Apus introduced by Carl von Linné for the genus and species is derived from the Greek: άπους ( ápus ) means “without feet” - in fact, the legs are very short and deeply hidden in the plumage during flight and thus not to see.

Legends

Although swifts have long been at home in towns and small towns, they have not received special attention from the population; there is comparatively little evidence of mythical properties of these birds. In some areas of England the swifts had the reputation of being "devil birds" or "screech devils". Her sudden appearance at the beginning of summer, along with the black plumage and loud screaming, made people scary. In contrast, the Tyroleans rated the swifts positively, because there they were considered lucky charms and slipped into the role that was intended for smoking and house martin in Germany. A useful application from folk medicine has also come down to us from Pliny , namely, it should be possible to treat stomach anger with swifts soaked in wine.

Nesting aids

Swifts used to inhabit cavities in buildings, which in the past often resulted from the construction of the roof structure. As a rule, the nesting sites could only be discovered when the birds entered and exited, as a narrow slot is sufficient for the birds to enter. To produce an airtight building envelope, modern roofs are usually hermetically sealed. Ventilation openings are protected from the entry of animals with grilles and net straps. This drastically reduces the nesting opportunities for cave breeders .

In the case of new construction or renovation of buildings, it is easy to create nesting opportunities for swifts. Carpenters or roofers can provide eaves boards or roof boxes with elongated holes about 33 × 60 mm in size, which only swifts and titmice allow entry. Holes with a 50 mm diameter also allow the house sparrow to use it. Ready-made incubators are also available, which can be placed in the wall instead of a brick or integrated into the insulation layer. After plastering the wall, the entry openings are barely visible. In contrast to swallows , which make their nests out of clumps of clay, swifts do not pollute the facade. The swifts, which weigh only 40 grams, do not produce any significant amounts of faeces. Regular cleaning of the cavities used for breeding is not necessary.

The breeding season lasts from the end of April to the end of July or mid-August at the latest.

literature

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim (Hrsg.): Handbook of the birds of Central Europe (HBV). Volume 9: Columbiformes - Piciformes. AULA-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X .

- Phil Chantler, Gerald Driessens: A Guide to the Swifts and Tree Swifts of the World. Pica Press, Mountfield 2000, ISBN 1-873403-83-6 .

- Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky: remarks about swifts. Niebühl 2003, ISBN 3-89906-463-1 .

- David Lack : Swifts in a Tower. Chapman & Hall, 1973, ISBN 0-412-12170-0 .

- Jochen Hölzinger , Ulrich Mahler: The birds of Baden-Württemberg: Non-songbirds. Volume 3, Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-8001-3908-1 , pp. 305-318.

- Emil Weitnauer: My bird: From the life of the common swift Apus apus. 1980, 6th edition 2005.

- Gérard Gory: Common Swifts: Life in Flight. Spectrum of Science, April 2005, ISSN 0170-2971 , pp. 28-32.

Web links

- Apus apus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 31 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings for Apus apus in the Internet Bird Collection

- International website about swifts

- German Society for Swifts : Fundvogel

- Information and audio about the common swift

- Private swift website from Berlin

- Common swift side with webcam

- Construction and installation of sailors nest boxes in

- Nest box camera of the Hans Herrmann primary school in Regensburg

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 3.1 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (Eng.)

- Swift feathers

- Rorýs obecný (Apus apus)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d Hedenström et al .: Annual 10-Month Aerial Life Phase in the Common Swift Apus apus. In: Current Biology. 2016, doi: 10.1016 / j.cub.2016.09.014

- ↑ a b c d e f g HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, walks. Pp. 680-686, see literature

- ↑ a b c d e HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: movement. P. 697 ff., See literature

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, field identifier, description. Pp. 671-676, see literature

- ↑ a b c d e f g Chantler, Driessens: A Guide to the Swifts and Tree Swifts of the World. Pp. 221-224, see literature

- ↑ a b c d e Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 8–15, see literature

- ↑ HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, moult. P. 676 f., See literature

- ^ Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. P. 22 f., See literature

- ^ Title page and foreword by Nature from April 26, 2007

- ↑ David Lentink et al .: How swifts control their glide performance with morphing wings. In: Nature. 446, 1082-1085, April 2007, doi: 10.1038 / nature05733

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, voice. P. 677f, see literature

- ^ A b Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 61-66, see literature

- ↑ a b c d e Erich Kaiser: Fascinating research on a domestic bird. In: alke 50: 10-15, 2003, ISSN 0323-357X

- ↑ HBV Volume 9: A. apus. Distribution of the art. P. 671, see literature

- ↑ HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, breeding area, distribution in Central Europe. P. 678 f., See literature

- ↑ a b Hölzinger, Mahler: The birds of Baden-Württemberg. see literature

- ↑ a b c HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, biotope. P. 686 f., See literature

- ^ A b c Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 41-51, see literature

- ↑ a b c d Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 53-60, see literature

- ^ Brunno Bruderer: Three decades of tracking radar studies on bird migration in Europe and the Middle East. In: Y. Leshem et al .: Proceedings International Seminar on Birds and Flight Safety in the Middle East. Pp. 107–141, Tel-Aviv 1999 ( online )

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, food. P. 709f, see literature

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: food acquisition. P. 701 f., See literature

- ^ A b Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 29-35, see literature

- ↑ a b c HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: social behavior. P. 702 ff., See literature

- ↑ a b c d e HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: rest, cleaning. P. 699 ff., See literature

- ↑ a b c d e f HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, reproduction. Pp. 688-693, see literature

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, inventory, inventory development. P. 679, see literature

- ↑ cf. Konrad Lorenz: Observations on jackdaws . tape 75 , no. 4 . Journal for Ornithology, 1927, p. 512 ( klha.at [PDF; 142 kB ; accessed on July 16, 2017]).

- ↑ a b c HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: sexual behavior. P. 704 f., See literature

- ↑ Chantler, Driessens: A Guide to the Swifts and Tree Swifts of the World. P. 27, see literature

- ^ Thais LF Martins: Low incidence of extra-pair paternity in the colonially-nesting swift (Apus apus) revealed by DNA fingerprinting. In: Journal of Avian Biology. 33: 441–446 ( Uncorrected Proof ( Memento from October 31, 2008 in the Internet Archive ))

- ↑ a b c d HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: brood care, rearing and behavior of the young. P. 707 ff., See literature

- ^ A b Gérard Gory: Common Swift - Life in Flight. see literature

- ^ J. Wright, S. Markman, SM Denney: Facultative adjustment of pre-fledging mass loss by nestling swifts preparing for flight. In: Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society. Volume 273, number 1596, August 2006, pp. 1895–1900, ISSN 0962-8452 , doi: 10.1098 / rspb.2006.3533 , PMID 16822749 , PMC 1634777 (free full text)

- ↑ a b c HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, breeding success, mortality, old age. Pp. 693-696, see literature

- ↑ a b c d Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 25-28, see literature

- ↑ HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: activity. P. 696 f., See literature

- ↑ a b Adriaan M. Dokter, Susanne Åkesson, Hans Beekhuis, Willem Bouten, Luit Buurma, Hans van Gasteren, Iwan Holleman: Twilight ascents by common swifts, Apus apus, at dawn and dusk: acquisition of orientation cues? In: Animal Behavior. Volume 85, pp. 545-552, doi: 10.1016 / j.anbehav.2012.12.006

- ^ A b Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 81-88, see literature

- ↑ a b HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, behavior: aggressive behavior, enemy behavior. P. 705ff, see literature

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Germany): 2003

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Switzerland): 2005

- ^ EJM Hagemeijer, MJ Blair (eds.): The EBCC Atlas of European Breeding Birds: Their Distribution and Abundance. T & AD Poyser, London 1997

- ↑ BirdLife International: Birds in Europe (2004) - Population development and status - Apus apus (PDF)

- ↑ HBV Volume 9: A. a. apus, population density. P. 687 f., See literature

- ↑ Carina Seeburg: Fly, Lumpi, fly! The modern architecture makes the birds homeless. In: SZ.de . August 2, 2018, accessed on October 22, 2018 : "When you arrive here and no longer find your home, you can often see them circling around for days."

- ↑ Where are the swifts? orf.at, May 17, 2018, accessed May 17, 2018. - Radolfzell Bird Observatory

- ^ Stefan Bosch: Sailors in the summer sky. Pp. 17-21, see literature

- ↑ HBV Volume 9: A. apus. Racial classification. P. 671, see literature

- ↑ Sven Baumung: Swifts: Bird of the Year 2003. NABU Germany, Bonn 2002 (ed.)

- ^ Hugo Suolahti: The German bird names. A verbal study. 1909 ( excerpt )

- ↑ PLEDARI GROND. Retrieved July 30, 2018 (Romansh).

- ↑ Pliny the Elder : Naturalis historia , Liber XXX, LX

- ↑ Katrin Koch, Jens Scharon: Nature conservation at the house , brochure of the Naturschutzbund Deutschland (NABU) eV, Landesverband Berlin, www.berlin.nabu.de

- ↑ Klaus Roggel: Active environmental protection - Fascinating experiences with swifts - don't you want to join in too?

- ↑ Klaus Roggel: Installation boxes on facades made of masonry, plaster and thermal insulation (ETICS)