Great curlew

| Great curlew | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Curlew ( Numenius arquata ) |

||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||

| Numenius arquata | ||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

The curlew ( Numenius arquata ) is a bird art from the family of the Waders (Scolopacidae). There are two subspecies. The nominate form is an increasingly rare breeding and summer bird in Central Europe. The 2015 Red List of Germany's breeding birds lists the species in Category 1 as critically endangered. It is a regular migrant and resting bird during migration times, and in some areas it also hibernates.

In Germany the curlew was bird of the year in 1982 .

description

Adult birds

The curlew is about 50 to 60 cm long and weighs between 600 and 1000 grams. The wingspan is 80 to 100 cm. The birds are the largest waders , and they are the most common curlews in Europe . A characteristic feature of the curlew is the long and strongly curved beak. The female is slightly larger than the male and has a much more curved and longer beak. Otherwise, the sexes look the same.

Large curlews are rather inconspicuous in color. The head, neck, chest and upper side of the body are pale beige-brown with dark stripes and spots. The cheeks are darkly dashed and thus contrast with the light spot on the chin and throat. The chest is slightly more strongly striped and becomes lighter towards the belly. In flight the white rump becomes visible, which forms a white wedge with the white back.

Fledglings

The down dress is cream-colored to light rust-brown with black-brown markings on the upper side of the body. The underside of the body is also cream-colored, but the chest is a little darker. Dark lines run from the beak to the blackish-brown vertex, which is slightly lightened in the middle. The dark eye stripe runs to the neck. A narrow dark stripe runs from the neck, which forks into two wider stripes on the coat. There is an irregular annular spot on the back of the back that encloses a lighter spot. The beak is initially short and straight and in fledgling juveniles it is a little longer and slightly curved. The legs and toes are pale gray with dark gray claws.

voice

The voice is a loud, very melodic sounding, wistful call that sounds like "kuri li". This reputation probably earned him the name "Curlew" in the English-speaking world. To mark the breeding grounds, the males sing a fluting and trilling verse in spring. Large curlews utter a "tlüih" when they fly, which turns into a "tüi-tüi-tüi" when excited.

habitat

The curlew breeds in moors and wet meadows as well as in open marshes . Its preferred habitat during the breeding season are large, open, easily manageable moist rain bogs. It also breeds in bog heaths, on Calluna heaths with wetlands, on wet grassland and occasionally on fields if these are close to grassland.

In winter the curlews live on the coasts and in the tidal flats , as well as inland in fields and wet meadows. Their main areas of distribution are northern and central Europe and the British Isles; in Germany they are found in the humid lowlands of the Weser-Ems region. In winter, the birds migrate to the coasts of western and southern Europe.

distribution

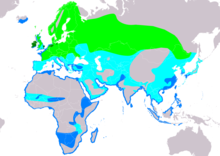

The curlew's huge distribution area extends in the west from Iceland to the Alps , in the east from Lake Baikal and Manchuria to Kazakhstan and the northern edge of the inner-Asian highlands in the southeast. The curlew is predominantly a short-range migrant , the breeding birds of Ireland and Great Britain are partly resident birds .

The majority of the northern European population moves southwest from June to the coasts of Great Britain and the coasts from Denmark to Iberia, Morocco and Mauritania. At the height of the migration in July and August, many adult birds can be found on the North Sea coast and moult there. Young birds join them from mid to late September, many of which overwinter in this area. Southeast European breeding birds overwinter mainly in the Mediterranean.

Subspecies

There are two subspecies. The nominate form Numenius arquata arquata occurs in the European part of the distribution area as well as in western and central Siberia and in Central Asia, northern Mongolia and Manchuria. They winter in the Middle East, in tropical Africa as far as South Africa, on the Indian subcontinent, in China, Japan and in Southeast Asia as far as the Great Sunda Islands. East of the Volga-Ural line to Kazakhstan comes Numenius a. orientalis . Birds of this population appear lighter overall, the extent of the dark feather markings on the underside and on the rear back is less. The beak is a little longer, as is the length of the wings. Both subspecies are not clearly separated from each other in the border area, there is great overlap in terms of size and color. The wintering area of this subspecies has so far been insufficiently researched, but it is assumed that they winter in Africa.

nutrition

Large curlews eat insects , worms and snails , which they look for with their long beak on and in the ground. The beak also doubles as a pair of tweezers to pull snails and clams out of their shells. On the migration and in winter, curlews look for food in coastal freshwater marshes and on tidal flats in the intertidal zones. In the tidal flats they prefer to feed on small beach crabs, while gnats dominate the freshwater habitats .

Large curlews locate their prey visually and with their sense of touch. They repeatedly probe the mud at shallow depths with their beak as they walk forward. If they locate a prey animal, it is grabbed by deeper poking movements. This is then pulled out of the ground by turning the head and neck. Crabs are shaken vigorously by them and thrown on the ground to remove the limbs. Prey that are on the surface are often hunted in short spurts.

Brood care

The nest is a shallow hollow on the ground that is sparsely padded with old (dried) grass or moss from the surrounding area. The nesting hollows are created by the male, who occasionally scratches several nesting hollows, from which the female chooses one. The breeding season begins in late April to early May. The clutch usually consists of four eggs, less often three or five eggs. These have an oval to spherical shape and a smooth, slightly shiny shell. They are light green, olive green or dark olive colored and marked with smaller, relatively dark spots. The laying interval is usually two days. Both parent birds breed alternately, but the male usually breeds far less than the female.

The chicks flee the nest and leave the nest as soon as the down is completely dry. In the first few days of life they are led by both parent birds, later only the male leads them. When they are growing up, they are dependent on loose, not too high vegetation, as they cannot move forward in grass that is too dense and then starve to death. They are fully fledged at around five to six weeks.

Duration

Inventory development and current inventory

During the 19th century the curlew lost many suitable Central European breeding areas due to the drainage of bog areas. At the same time, however, new breeding opportunities arose on extensively used wet grassland in the lowlands, which arose after clearing alluvial forests. This led to a spread of the species and an increase in the population areas in large parts of Central Europe. Since the 1950s, there has been a significant decline in populations in large parts of Central Europe, after hay meadows and pastures have been used more intensively. A high degree of loyalty to the breeding site and the long lifespan of the species simulates intact breeding populations over a longer period of time. However, the breeding success of the curlew is no longer sufficient to maintain the population in many regions . The lack of offspring therefore inevitably leads to a collapse of the population if there is no immigration of birds.

The total European population is estimated at 220,000 to 360,000 breeding pairs at the beginning of the 21st century. Of these, between 50,000 and 80,000 breeding pairs occur in Fennoscandinavia , 48,000 to 120,000 breeding pairs in the European part of Russia and 99,000 to 125,000 breeding pairs in Great Britain. 11,000 to 13,000 breeding pairs breed in Central Europe.

Inventory forecast

The curlew is considered to be one of the species that will be particularly hard hit by climate change. A research team that, on behalf of the British Environmental Protection Agency and the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), examined the future development of the distribution of European breeding birds on the basis of climate models, assumes that the range of the curlew will last until the end of the 21st century will shrink by more than forty percent and move further north. According to this forecast, potentially colonizable regions will arise on Iceland, in the far north of Russia, on Novaya Zemlya and possibly a small area on Svalbard . As a Central European breeding bird , the curlew is likely to remain, but its range is likely to decrease significantly.

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel , Wolfgang Fiedler (eds.): The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 1: Nonpasseriformes - non-sparrow birds. Aula-Verlag Wiebelsheim, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89104-647-2 .

- Peter Colston , Philip Burton: Limicolen - All European wader species, identifiers, flight images, biology, distribution. BlV Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-405-13647-4 .

- Simon Delany, Derek Scott, Tim Dodman, David Stroud (Eds.): An Atlas of Wader Populations in Africa and Western Eurasia. Wetlands International , Wageningen 2009, ISBN 978-90-5882-047-1 .

- Otto von Frisch: The Curlew. (The new Brehm library 335). Wittenberg Lutherstadt 1964.

- Collin Harrison and Peter Castell: Fledglings, Eggs and Nests of Birds in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Aula Verlag, Wiebelsheim 2004, ISBN 3-89104-685-5 .

Web links

- Numenius arquata in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 2 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Numenius arquata in the Internet Bird Collection

- Further information and pictures at the Wattenmeer eV protection station

- Meadow bird protection Protection program for curlews in the Emsland

- Curlew feathers

Individual evidence

- ↑ Christoph Grüneberg, Hans-Günther Bauer, Heiko Haupt, Ommo Hüppop, Torsten Ryslavy, Peter Südbeck: Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds , 5 version . In: German Council for Bird Protection (Hrsg.): Reports on bird protection . tape 52 , November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Hans-Günther Bauer, Einhard Bezzel and Wolfgang Fiedler (eds.): The compendium of birds in Central Europe: Everything about biology, endangerment and protection. Volume 1: Nonpasseriformes - non-sparrow birds. Aula-Verlag Wiebelsheim, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89104-647-2 , p. 464.

- ↑ Bird of the Year (Germany): 1982

- ↑ a b Collin Harrison, Peter Castell: Young birds, eggs and nests of birds in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Aula Verlag, Wiebelsheim 2004, ISBN 3-89104-685-5 , p. 144.

- ↑ Martin Flade: The breeding bird communities of Central and Northern Germany - Basics for the use of ornithological data in landscape planning . IHW-Verlag, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-930167-00-X , p. 544

- ↑ Peter Colston, Philip Burton: Limicolen - All European wading bird species, identifiers, flight images, biology, distribution. BlV Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-405-13647-4 , pp. 185-186.

- ^ A b Simon Delany, Derek Scott, Tim Dodman, David Stroud (Eds.): An Atlas of Wader Populations in Africa and Western Eurasia. Wetlands International , Wageningen 2009, ISBN 978-90-5882-047-1 , p. 307.

- ↑ a b Colston et al., P. 186.

- ↑ Bauer et al., P. 466

- ↑ Bauer et al., Pp. 464-465.

- ^ Brian Huntley, Rhys E. Green, Yvonne C. Collingham, Stephen G. Willis: A Climatic Atlas of European Breeding Birds , Durham University, The RSPB and Lynx Editions, Barcelona 2007, ISBN 978-84-96553-14-9 , P. 194