Cormorant (species)

| cormorant | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Great cormorant ( Phalacrocorax carbo ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Phalacrocorax carbo | ||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

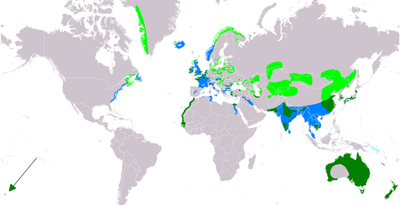

The great cormorant ( Phalacrocorax carbo ) is a species of bird from the family of cormorants (Phalacrocoracidae). The range of the species includes large parts of Europe, Asia and Africa, also Australia and New Zealand as well as Greenland and the east coast of North America. As with all members of the genus Phalacrocorax, the diet consists almost exclusively of fish. Cormorants are sociable in all seasons, the breeding colonies are on coasts or larger bodies of water. The existence and distribution of the species in Europe were strongly influenced by massive human persecution, in the Central European inland the species was almost extinct at times. There has been a significant recovery in the population over the past few decades. The cormorant was bird of the year 2010 in Germany and Austria .

designation

The German name of this bird species comes from the old French cormareng or from the even older form corp mareng " Meerrabe , Wasserrabe" and ultimately goes back to the late Latin corvus marinus with the same literal meaning. The part of the name “raven” can also be found in his scientific name: like corvus, corax means “raven” in Latin and is a direct borrowing from the ancient Greek κόραξ . Phalacro (φαλακρός) is also of Greek origin and means “bald”, which according to some ornithologists refers to the pale white head feathers. However, it may also be that the name originally referred to a different way. The specific epithet carbo "coal" stands for the predominantly black color of the plumage.

German-language names that did not catch on are e.g. B. (the) Scharbe or (the) Scholver . However, “Scharbe” instead of “Kormoran” is used in the German name of many other types of cormorant.

description

Cormorants are barely the size of a goose, they are 77 to 94 cm long and have a wingspan of 121 to 149 cm. Males are slightly larger and heavier than females. The weights of males vary between 1975 and 3180 g, females reach 1673-2555 g. Male breeding birds on Rügen had wing lengths of 334 to 382 mm, on average 358.5 mm, females there reached 321 to 357 mm, on average 335.0 mm. As with all species of the genus, the relatively large beak is hook-shaped at the end.

In breeding plumage , the plumage of the spread in Central Europe subspecies P. c. sinensis predominantly black, in the sunshine the feathers shine metallic green or bluish. The feather feathers of the upper wing shimmer bronze-colored and have a glossy black border, the upper wing therefore appears flaky. The crown and neck are interspersed with fine white feathers. At the back of the head there is a tuft that is created by protruding feathers about 4 cm long. At the base of the beak there is a bare, yellow area of skin with a broad white border, and the outer thigh base shows a white spot. The sexes do not differ in terms of coloration.

The plain dress lacks the white fletching on the crown and neck and the white spot on the thighs. The white area at the base of the beak is wider, dirty white and less sharply set off from the otherwise black neck and head plumage. The crest is only indicated.

Birds of the subspecies P. c. sinensis are youth dress predominantly brown to black brown, the upper side shows a faint metallic sheen. The shoulder feathers and the wing-coverts are brown with shiny black-brown edges. The sides of the neck are dashed in white, the feathers on the throat and front chest have a whitish border. Tail feathers and wings are black-brown with light tips, the arm wings show less steel luster than those of adult birds. The underside of the trunk is very variable and brownish or dirty white to very different extents, only rarely pure white. The head, neck and the base of the thighs show numerous white hair feathers that end with a fine brush. The animals are colored after four years.

The plumage of the cormorant because of its structure absorbs water, which reduces buoyancy, so that the bird lies very deep in the water. When a cormorant leaves the water, it first shakes out its plumage. Then it spreads its wings so that its wet plumage dries faster.

In adult birds the iris is emerald green, in younger birds it is gray-brown or gray-green. The upper bill is lead-gray with a blackish ridge ; the lower bill is horn-yellow, at the tip gray. The legs and feet are black in all age groups.

Vocalizations

Cormorants are mostly mute away from their breeding grounds. The calls in the colonies are deep and croaky. The most common call sounds something like “chrochrochro”; this reputation is varied. The voice feeler calls can be described as "chroho-chroho-chroho", the calls when prompted to mate sound like "kra-orrr" or "à-orrr".

distribution and habitat

The range of the species includes large parts of the Old World , also Australia and New Zealand as well as Greenland and the east coast of North America. Cormorants are bound to water, the breeding colonies are located on the coast of the sea as well as on the banks of larger rivers and lakes.

Systematics

Usually six subspecies are recognized:

- P. c. carbo ( nominate form ): Eastern Canada via Greenland and Iceland to the British Isles and Norway.

- P. c. sinensis : Central and Southern Europe to India and China in the East; smaller and greener and usually more white on the throat than P. c. carbo .

- P. c. hanedae : Japan, possibly synonymous with P. c. sinensis .

- P. c. marrocanus : Northwest Africa; Staining between P. c. sinensis and P. c. lucidus .

- P. c. lucidus ( white-breasted cormorant ): coastal areas of western and southern Africa, inner East Africa, smaller and greener than the nominate form, the white area usually extends to the chest or belly, also occurs in a dark morph that is found on P. c. sinensis reminds; often viewed as a distinct species.

- P. c. novaehollandiae : Australia, Tasmania, New Zealand, Chatham Islands , is occasionally divided into further subspecies ( P. c. carboides in Australia and P. c. steadi in New Zealand), could also represent an independent species.

Way of hunting and food

The hunt for fish is done diving, dives are usually initiated with a small jump. The normal dive duration is 15–60 s at depths of usually 1–3 m, but up to 16 m has been proven. Movement under water is done with the feet, fish are grabbed with the hooked bill behind the gills.

The food consists almost exclusively of small to medium-sized sea and freshwater fish, these are captured alive. Other water-bound animals such as crabs and large shrimps are rare chance prey. Muskrats and chicks of the shelduck have very rarely been identified as prey.

Cormorants opportunistically hunt those fish that are abundant and most readily available; the composition of the food therefore varies greatly depending on local conditions and the time of year. In the German inland lakes, it is predominantly the white fish , which often appear in large schools, that are captured. Along with carp fish , grayling and other salmonids can form a larger part of the diet in rivers with higher flow speeds .

In Bavaria, the winter diet of the cormorant was investigated in natural pre-Alpine lakes ( Ammersee , Chiemsee ), on artificial waters ( Altmühlsee , Ochsenanger, Unterer Inn ) and on river sections ( Danube , Alz ). The majority of the captured fish were 9 to 28 centimeters long. In all waters, indefinite carp fish (Cyprinidae) formed the main part of the diet, depending on the body of water with 37.3–65.8% of all prey fish. Other important species were perch with 4.2 to 20.9 percent and roach with 1.0 to 10.5 percent. In the foothills of the Alps, whitefish ( Coregonus sp.) Also played a more important role with 9.5 percent. Even in the Alz, which was still partially natural, undefined carp fish were by far the most common prey with 52.9 percent, followed by grayling with 12.6 percent and undefined salmonids with 11.0 percent of all prey fish.

Anglers regularly claim that the cormorant endangers or even exterminates stocks of grayling and other species. In response to a small request from the Die Linke parliamentary group in the Bundestag, the federal government made it clear in its response, “that there is no reliable evidence that the cormorant threatens a species of fish. Only at the regional level cannot be ruled out that there will be reductions in the grayling population in individual cases. ”In the event of a population decline, the ecological conditions of the water bodies must always be considered. Investigations on Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland by the Zurich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW) on behalf of the Federal Office for the Environment (FOEN) revealed that the professional fishermen there had shown the damage far exaggerated.

Reproduction

Cormorants breed in colonies, which can contain several thousand breeding pairs in suitable locations. The nests are built on the coast, depending on the conditions, on cliffs or on the ground, inland mainly on tall trees by water. Cormorants usually breed for the first time at the age of 3 or 4 years, rarely as early as 2 years. The breeding pairs probably live predominantly in a monogamous seasonal marriage. Both partners build the nest from branches that are broken off or taken out of the water. The nest hollow is padded with finer material, often with seaweed on the coast .

The clutch usually consists of 3 to 4, rarely 5 and extremely rarely 6 eggs. The eggs are elongated oval and a single color, light blue, about 94 × 39 mm in size (very variable). The light blue color is barely visible due to a chalky white coating. In Central Europe, eggs are laid mainly from the end of April to June. Both partners incubate, the breeding season is 23–30 days. The young birds are fed by both partners with gagged fish. The nestling time is about 50 days, with 60 days the young birds are fully capable of flight. After flying out, the offspring are provided with food by their parents for 11–13 weeks.

Age

In exceptional cases, cormorants can reach an age of over 20 years. The highest proven age should be over 27 years. The oldest bird ringed in Germany and later observed alive was at least 21 years old.

hikes

Depending on the population, cormorants are resident birds , partial migrants or migratory birds . The coastal population of the subspecies P. c. carbo in Ireland and Great Britain migrates undirected along the western European Atlantic coasts, south to northern Portugal. The Dutch cormorants of the subspecies P. c. sinensis are partial migrants, the further eastern populations are probably all migratory birds and migrate at least over short distances. The main migration in Central Europe takes place in October and November, after which winter flight occurs. The winter quarters of Central European breeding birds extend to Great Britain, North Africa and the Eastern Mediterranean. The return to the breeding colonies in the Netherlands takes place as early as January or February, further east in March and April.

Natural enemies

In the angling and hunting press it is regularly claimed that "the cormorant" has no natural enemies and that its populations are growing absolutely uncontrollably. Indeed, there is evidence of cormorant colonies with massive predation . In this raccoon , raccoon dog (at bottom nests), Mink , fox (at ground nests and low bushes), Habicht , eagle , eagles , owls , herring and Nebelkrähe determined as predators. The only colony in the USA on a coastal island in the state of Maine is predicted by bald eagles. Individual colonies were given up, especially when predated by raccoons. At the Gülper See , the Brandenburg State Environment Agency found that a colony with 800 breeding pairs had been abandoned after raccoons had settled at the colony. In the years 2008 and 2009 no successful breeding of raccoons was found in three colonies of Brandenburg, in parts of other colonies there were massive losses to raccoons. Even with predation by white-tailed eagles and eagle owls, it was found that colonies shifted or that parts split off. Smaller colonies also disappeared completely when predated by the sea eagle.

White-tailed eagles kill both adult and young birds, and in some cases they also bring young birds out of nests. The attacks mostly come from immature, i.e. not fully grown, eagles. Most of the time, white-tailed eagles fly fake attacks, which cause the cormorants to strangle fish. The sea eagles then eat this strangled fish. In the colony of Polder Wehrland / Waschow, cormorants settled around a sea eagle nest and eventually even brooded in the same tree as the sea eagles. There were no attacks by these breeding eagles on the breeding neighbors. Eagle owls also breed in colonies in individual cases, e.g. B. Haseldorf nature reserve , without causing conflicts.

Persecution by people

Written evidence of massive persecution of the cormorant with the destruction of breeding colonies has existed since the second half of the 17th century. In the 19th century, the brood distribution of the cormorant in the German Empire was characterized by frequent changes of colony locations, as the species gave up colonies after a short time due to massive persecution and founded new ones elsewhere. At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, there were only colonies in the German Empire in the provinces of Pomerania, West and East Prussia. Because of the supposed fishing and forestry damage, every cormorant settlement was massively fought by fishermen, landowners and authorities. For the forest and fisheries authorities, fighting cormorants was one of the regular tasks. In the 1830s even soldiers from the Guard Hunters Battalion from Potsdam were used to fight cormorants. There were also launch bonuses. The City Council of Szczecin paid 2.5 silver groschen for a pair of catches of the cormorant. Even ornithological associations took part in the fight against a “harmful” bird species such as the cormorant. The first protective measures were implemented from the beginning of the 20th century. These came from aristocratic landowners who tolerated colonies on their land. The Pulitz colony in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania was the first colony to be explicitly designated as a nature reserve because of the cormorants from 1937 until the Second World War .

In Europe many thousands of cormorants are currently killed by shooting each year. Current figures assume around 80,000 cormorants killed by shooting in the EU. Of these, around 15,000 were killed in Germany. The kills are distributed very differently across Germany. In North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), 5,115 cormorants were killed in the 2009/2010 hunting season. In NRW were z. B. Shooting outside of nature reserves from September 16 to February 15 is permitted by state ordinance. For shooting in nature reserves, special permits had to be applied for. The legal situation has changed several times in recent years and is also different in every country or federal state. The kills were in fishing and hunting magazines z. B. celebrated “as a preventive stabilization of fish stocks”. In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania there were actions that resembled the extermination campaigns of the 19th century; in June 2005 around 6,000 cormorants were shot down near Anklam (compared to 900 in 2013 in total MV ). This case, which made headlines as the “Anklam Cormorant Massacre”, was a setback, especially for nature conservation, as the birds were shot down in a nature reserve and during the breeding season. As numerous official requirements were violated, protests broke out from home and abroad. The responsible ministry of the environment felt compelled to put the cormorant management in Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania to the test. In the previous results of these tests, measures against the cormorant are no longer permitted solely on the basis of the assumption of considerable damage to the fishing industry, but are strictly aligned with the requirements of the legislature.

In addition to shooting, there are other persecution measures. These include oiling clutches and replacing eggs with artificial eggs to prevent cormorants from hatching. Furthermore, the nest trees or potential nest trees were felled again and again, even during the breeding season. In April 2008, in a nature reserve in Radolfzeller Aachried on Lake Constance, brooding cormorants were driven from their nests with searchlights. Many of the eggs died in the cold night.

In addition to the fatal measures, deterrence measures were also carried out. Optical (with balloons, flutter tapes and mirrors) and acoustic measures (playing calls from enemies) and shooting with laser rifles were used. The deterrence measures proved to be ineffective or too costly and were later discontinued.

INTERCAFE ( Conserving biodiversity: interdisciplinary initiative to reduce pan-European cormorant-fishery conflicts ) dealt with the cormorant problem in eight workshops from 2004 to 2008 . 70 experts, including ornithologists, ecologists, fishery biologists, fishery managers, sociologists, lawyers etc. from almost all EU countries and other countries such as B. Norway and Israel participate. An INTERCAFE toolbox was developed with suggestions for reducing the problems. In the process, deterrent measures, measures to protect the fish such as network surges, wire surges, design of fish farming facilities, artificial refuge for fish, improvement of the habitat quality for fish, fish stocking and stock management, removal of resting and sleeping areas, removal of nests, shooting, reduction of the breeding success and financial compensation investigated and evaluated.

Existence and endangerment

Cormorant population

Just like other fish-eaters such as ospreys , gray herons , otters or kingfisher , the cormorant was massively persecuted as a supposed food competitor of humans in Europe and population and distribution were therefore strongly influenced by humans. In inland Central Europe the species was practically extinct by 1920. In Germany, the last breeding colonies existed in Schleswig-Holstein until 1905 and in Lower Saxony until 1919. In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania there were no more breeding colonies known in 1900 and the last colony in Brandenburg was destroyed as early as 1883. The repopulation of Germany began hesitantly from around the mid-1940s from the Netherlands and Poland, where the species had survived in large numbers as a breeding bird. Lower Saxony was repopulated in 1947, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania in 1950, Brandenburg from 1965 and Schleswig-Holstein from 1982. In Germany, 23,500 to 23,700 pairs brooded in 2005.

In Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (at that time the three northern districts of the GDR) there were only 2,000 breeding pairs in 1985, there were up to 14,500 breeding pairs at the maximum in 2008. Reasons were the resettlement of the cormorants in Peenemünde after the airfield was closed and the renaturation (rewetting ) of the Anklamer city break. After that, the number fell again due to the cold winters of 2009/2010. The three largest colonies in Germany are located on the Baltic Sea coast of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania (MV). In 2011 the colony in the nature reserve Kormorankolonie near Niederhof had 1,948 breeding pairs, Peenemünde on Usedom 2,118 and Anklamer Stadtbruch 2,026. In total there were 8,800 breeding pairs in MV. In MV there are other smaller colonies on the south coast of Rügen and on inland lakes.

In 2012 the number of breeding pairs in MV increased again, from 8,800 to 11,500 and fell again in 2013 due to the long winter.

In neighboring Poland there is a larger colony in Dziwnów , where the typical limed trees can be seen (see photo).

In Austria there was still a relatively large colony (up to 300 breeding pairs) in the Lobau near Vienna in the first quarter of the 20th century, which was increasingly decimated by shooting from 1915 and completely abandoned after 1926. However, some smaller breeding colonies remained for several decades. The colony near Orth (Danube) was continuously occupied from 1919 to 1966, the last breeding colony near Marchegg (March) was severely decimated by hunting from 1960 and was no longer occupied after the 1971 breeding season. It was not until 2001 that permanent breeding colonies established themselves again in Austria. The population grew quickly to 235 pairs by 2008, but then fell sharply as a result of population-regulating measures in the Lake Constance colony. In the last complete survey in 2012, only 65 breeding pairs were counted at the three locations (Bodensee, March-Auen, Neusiedlersee). In 2014, there was again an upward trend at Lake Constance (65 pairs) and Lake Neusiedl (23 pairs).

The cormorant was a migrant in Switzerland until 1940 and then began to overwinter in small numbers. From 1967 the winter population grew slowly at first, from around 1980 then very strongly in parallel with the increase in northern Europe. The maximum was reached in 1992 with around 8,500 birds, since then the winter population has declined again and has leveled off at 5,000–6,000 birds since the mid-1990s. Cormorants have been breeding in Switzerland since 2001, mainly in the Rhone Delta on Lake Geneva ( Les Grangettes nature reserve ) and with a small breeding population on Lake Neuchâtel. The population increased continuously, currently in 2014 1,504 pairs were counted in 11 colonies. The increase in cormorants in Switzerland cannot be held responsible for the general decline in fish stocks; however, the effects on grayling stocks, which are highly endangered by anthropogenic factors , are monitored locally.

Overall, there has been a significant increase in populations in Europe over the past few decades due to protective provisions. Around 24,000 breeding pairs live in Germany, and there are currently around 450,000 breeding birds in Western Europe. The world population was estimated by Birdlife International in 2009 at 1.4 to 2.9 million individuals.

Endangerment of certain fish species by cormorants

As the population increases, the negative impact of cormorants on certain fish stocks is discussed and problematized. In the winter of 1994/1995, swarms of cormorants invaded the waters for the first time in the low mountain ranges of North Rhine-Westphalia and decimated the brown trout and grayling stocks . In addition to the expansion of water bodies and the lack of water dynamics, the feeding pressure from cormorants is due to the decline in these fish species, which is a threat to the continued existence of these fish. In December 2008 the European Parliament requested the collection of scientific data as a basis for the creation of a pan-European cormorant management plan. On September 15, 2014, Saxony-Anhalt issued an ordinance to protect the natural fish fauna and to prevent considerable damage to the fishing industry caused by cormorants. For this purpose, authorized persons are allowed to hunt cormorants in certain areas and prevent the emergence of new breeding colonies. In the Aischgrund bird sanctuary ( Middle Franconia ), special permits for the limited shooting of cormorants were granted due to damage caused by the fishing industry. After two years, a deterioration in the conservation status of ornithological target species could be ruled out with a high degree of probability, while the damage to the fishing industry could be significantly reduced.

The food requirement of a cormorant per day was given by hunters and anglers to be 500 grams of fish, whereas from the scientific point of view, significantly less than sufficient. The information varies between 150 and 400 grams. Josef Reichholf from the Zoological State Collection in Munich puts the daily requirement at up to 150 grams and refers to a corresponding study on the bird's spit balls. The cormorant behaves no differently than other comparable birds, whose feed consumption in view of high-quality and protein-rich food (such as fish) is 5% of their own body weight, a maximum of 10%. According to Reichholf, when the cormorant is hunted, it is shy and forced to make frequent, energy-consuming flights. This increases the need for food, so that fewer cormorants can cause the same fish losses. In addition, the natural regulation of the cormorant populations was out of balance due to the decline of the sea eagle , the adult birds, but especially the young cormorants captured in the breeding colonies; therefore the resettlement of the bird of prey must also be supported. A large proportion of the prey fish of the cormorant are species such as sticklebacks and whitefish that are of no interest to the pond . For cormorants on the Baltic Sea, the biologist Helmut Winkler from the University of Rostock found that economically used species such as eels, herring and cod only make up two to four percent of the food spectrum.

Cormorant fishing

In Macedonia , cormorants (along with other piscivorous diving birds) may have been around since the 5th century BC. Used for fishing on Lake Dojran. The method used there was fundamentally different from the technology that has been demonstrable in China and Japan since the 3rd century. Even today, cormorant fishing is still practiced in some places, often as a tourist attraction, e.g. B. on the Li River near Guilin . In Macedonia there are evidently efforts to establish the local fishery as a tourist attraction as well.

Wild catches were used for European cormorant fishing. For this purpose, young cormorants were taken from nests in nature. In some regions of China, however, there is a real breeding of birds. However, since the females of breeding cormorants neglect their eggs in captivity, these are hatched by hens. The hatched chicks are raised by hand, where they are fed, among other things, with tofu . At around 100 days of age, both wild-caught and breeding cormorants are trained. The young birds learn the hunting behavior of older animals. Hand-raised cormorants are strongly influenced by their caregiver and are usually allowed to move freely. Wild-caught specimens or specimens bought from breeders are usually prevented from escaping with a string on the leg. Taming wild-caught birds is arduous and takes seven to eight months with two to three hours a day spent with the birds. You will be taught to sit on the edge of the boat or raft, to fish on command, and to get used to the neck ring. The birds learn to bring the catch to the boat, where the fish is taken from them by the master. A neck ring prevents the caught fish from being swallowed by the cormorant. The fisherman feeds the cormorant with individual smaller fish, pieces of fish or shrimp. In Japan catches of up to 150 fish per hour have been observed. The cormorants perform at their best between the ages of three and eight years. They are used for work for up to ten years.

Outside Macedonia, cormorant fishing was practiced by noblemen as a leisure activity from the middle of the 16th century and often took place in specially constructed ponds. The cormorants were looked after by falconers and, like birds of prey, were carried on the fist when hunting . The head was covered with a hood. In addition, as in China, neck rings were put on them. The oldest evidence goes back to a writing by Julius Caesar Scaliger from Venice . More precise dates are available from 1608 in English state files of the 17th century. The English royal courts of James I and Charles I owned a Master of Cormorants on. A cormorant keeper is mentioned here for the last time in 1689 . From 1846 to 1890, cormorant fishing was practiced by Francis Henry Salvin. In the falconry textbook Falconry, its claims, history, and practice from 1859, he devoted a chapter to cormorant fishing. In France there are records for the royal court between 1609 and 1736. Around 1625, the French King Louis XIII. and some other high-ranking personalities in the canals of Fontainebleau Castle demonstrated several tamed cormorants by a Flemish falconer employed at the English court and sent by the king there. In France there was for a time the post of garde des cormorants . Cormorant fishing was also carried out here in the 19th century. Further evidence exists for Austria and Holland. Evidence of the Volga from 1912 is available from Russia. Also in Germany, more precisely in Darmstadt in the 1770s and in Ballenstedt at the beginning of the 19th century, trained cormorants were presented at aristocratic courts.

Bird of the year 2010

The cormorant was 2010 bird of the year in Germany and Austria. In this way, the nature conservation associations that hold the bird of the year election wanted to make the discussion more objective. By anglers, fishermen and hunters cormorants were almost entirely irrelevant words like voracious birds , fish predators , fish thieves , Black combat divers , true scourge of the waters , the black invasion , Cormorant Plage shown, etc.. After the election for Bird of the Year, there was some massive criticism from anglers and there was talk of provocation. There were demonstrations and rallies by anglers against the cormorant. NABU and LBV, which had chosen the cormorant as bird of the year, set up the website www.kormoranfreunde.de. By the end of 2010, 2,166 cormorant friends registered on the site. At the conference on the cormorant as bird of the year in Ulm on March 20, 2010, there was a counter-demonstration by anglers with 3,000 to 4,000 participants. The NABU press office in Berlin evaluated the press coverage of the cormorant nationwide from October 2009 to October 2010. Of the 910 articles, around 50% were neutral, i.e. with balanced reporting, 27% reported positive and 23% negative about the cormorant, in that they only presented the opinions of anglers and fishermen. National newspapers reported consistently neutral and factual, while local papers mostly only presented the angler's point of view. Both an exaggeration and an objectification were noted.

literature

- Einhard Bezzel : Compendium of the birds of Central Europe. Nonpasseriformes - non-singing birds. Aula, Wiesbaden 1985, pp. 57-60, ISBN 3-89104-424-0 .

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim, Kurt M. Bauer: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe, Volume 1, Gaviiformes - Phoenicopteriformes. Aula, Wiesbaden, 2nd ed. 1987, pp. 239-261, ISBN 3-923527-00-4 .

- Josep del Hoyo , Andrew Elliot, Jordi Sargatal : Handbook of the birds of the World. Volume 1. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 1994, ISBN 84-87334-15-6 .

- Lars Svensson , Peter J. Grant, Killian Mullarney, Dan Zetterström: The new cosmos bird guide. Kosmos, Stuttgart 1999, pp. 28-29, ISBN 3-440-07720-9 .

- Manfred Pforr, Alfred Limbrunner: Ornithological picture atlas of the breeding birds of Europe, Volume 1. Nature, 1991, p. 43, ISBN 3-89440-007-2 .

Web links

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Phalacrocorax carbo in the Internet Bird Collection

- Phalacrocorax carbo in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed on December 15 of 2008.

- Bird of the year: 2010 cormorant

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 5.4 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (eng.)

- Feathers of the cormorant

Individual evidence

- ↑ Duden universal dictionary Kormoran

- ↑ Georges: Comprehensive Latin-German concise dictionary corax

- ↑ ibid.

- ↑ Peter Bertau: That's what our birds used to be called - a compilation of trivial and artificial names for native bird species . Springer Spectrum, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-662-59774-3 , p. 260 .

- ↑ Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim, Kurt M. Bauer: Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas, Volume 1, Gaviiformes - Phoenicopteriformes. Aula, Wiesbaden, 2nd ed. 1987: pp. 243–244

- ↑ RM Sellers: Wing-spreading behavior of the cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo. In: Ardea. No. 83, 1995, pp. 27-36

- ^ Josep del Hoyo, Andrew Elliot, Jordi Sargatal: Handbook of the birds of the World. Vol. 1. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona 1994.

- ↑ T. Keller: The food of cormorants in Bavaria. J. Ornithol. 139, 1998: pp. 389-400.

- ↑ a b Markus Nipkow, Andreas von Lindeiner, Helmut Opitz: The Cormorant - Bird of the Year 2010. A balance of NABU and LBV . Reports on Bird Protection 2011, Vol. 47/48: 31–43.

- ↑ Werner Müller: Myth pest invalidated . Ornis 2010, 5: 10-21.

- ↑ Fransson et al. in Fiedler, W., O. Geiter & U. Köppen, reports from the ringing centers, Vogelwarte 49 (2011), p. 35

- ^ Fiedler, W., O. Geiter & U. Köppen, reports from the ringing centers, Vogelwarte 49 (2011), p. 35

- ↑ a b c NABU (2009): The cormorant - bird of the year 2010. Berlin.

- ^ A b Thomas Brandt, Hans-Heiner Bergmann: Hunted hunter . Der Falke, special issue 2010: 26–31

- ↑ Ministry of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Areas of the State of Schleswig-Holstein (2011): Annual Report 2011 Hunting and Species Protection. Kiel

- ↑ MEISE, B. (2010): Raccoons rub the breeding colony of the cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo). Ornithological booklets Edertal 36: 111.

- ↑ LANDESUMWELTAMT BRANDENBURG (2010): Environmental data 2008/09. Potsdam.

- ↑ LANDESUMWELTAMT BRANDENBURG (2008): Report on the cormorant in the state of Brandenburg in 2007. Potsdam

- ↑ Christoph Herrman, Horst Zimmermann: Kormoran Phalacrocorax carbo . Contributions to the Avifauna Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, H. 3/2019: 23–68

- ↑ Anke Brandt: Do eagle owls ( Bubo bubo ) drive cormorants ( Phalacrocorax carbo ) out of their colony? Owl Circular 2019/69: 45–50.

- ↑ Christof Herrmann: The cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo sinensis in Mecklenburg and Pomerania from the late 18th to the middle of the 20th century. Bird World 132: 1-16.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Vanscheidt, Martin Lindner, Bernhard Koch (2011): The cormorant - About a fascinating, hated and persecuted species. Irrgeister 28: 60–64.

- ↑ MIEGEL, S. (2010): 150 hunters and anglers hunt down 78 water ravens. Rheinisch-Westfälischer Jäger 64.5: 18.

- ↑ taz.de : The Opportunist Amongst the Birds , 2009, accessed July 31, 2017

- ↑ NABU : Permanent kills are no solution , accessed July 31, 2017

- ↑ Florian Herzig and Anne Böhnke: Fachtagung Kormorane 2006 , accessed July 31, 2017

- ↑ BAUER, H.-G., E. BEZZEL & W. FIEDLER (2005): The Compendium of Birds in Central Europe - Nonpasseriformes - Non-singing birds. Wiebelsheim. Pp. 235-236.

- ↑ Thomas Keller: INTERCAFE Kormoran Toolbox . Der Falke, special issue 2010: 32–37

- ↑ Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim, Kurt M. Bauer: Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas, Volume 1, Gaviiformes - Phoenicopteriformes. Aula, Wiesbaden, 2nd ed. 1987: pp. 245–247

- ↑ Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim, Kurt M. Bauer: Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas, Volume 1, Gaviiformes - Phoenicopteriformes. Aula, Wiesbaden, 2nd edition 1987: p. 247

- ^ H. Zimmermann: Kormoran - Phalacrocorax carbo. In: G. Klafs and J. Stübs (Hrsg.): The bird world of Mecklenburg. Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden, 3rd edition 1987: pp. 90-92, ISBN 3-89104-425-9

- ^ E. Rutschke: Kormoran - Phalacrocorax carbo. In: E. Rutschke (Ed.): The bird world of Brandenburg. Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2nd edition 1987: pp. 99-100, ISBN 3-89104-426-7

- ^ RK Berndt, B. Koop and B. Struwe-Juhl: Vogelwelt Schleswig-Holstein. Volume 5: Breeding Birds Atlas. 2nd ed., Karl Wachholtz, Neumünster 2003, pp. 66–67, ISBN 3-529-07305-9

- ↑ P. Südbeck, H.-G. Bauer, M. Boschert, P. Boye and W. Knief: Red List of Breeding Birds in Germany - 4th version, November 30, 2007. Ber. Bird Conservation 44: 23-81.

- ↑ http://www.lung.mv-regierung.de/daten/kormoranbericht_mv_2011.pdf

- ↑ http://www.lung.mv-regierung.de/daten/kormoranbericht_mv_2013.pdf

- ↑ Aubrecht, Gerhard (1991). Historical distribution and current breeding attempts of the cormorant in Austria. In: Vogelschutz in Österreich Nr. 6. Communications of the Österr. Ornithology Society. [1]

- ↑ Parz-Gollner, R., T. Zuna-Kratky, W. Niederer & E. Nemeth, 2013: Status of the breeding population of Great Cormorants in Austria in 2012. - In: Bregnballe, T., Lynch, J., Parz-Gollner, R., Marion, L., Volponi, S., Paquet, JY. & van Eerden, MR (eds.) 2013. National reports from the 2012 breeding census of Great Cormorants Phalacrocorax carbo in parts of the Western Palearctic. IUCN-Wetlands International Cormorant Research Group Report. Technical Report from DCE - Danish Center for Environment and Energy, Aarhus University. No. 22: 10-13. [2]

- ↑ Niederer W., 2014. The cormorant in the Rhine Delta nature reserve. PDF ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. and Nemeth, Erwin. 2014. The breeding populations of the herons, spoonbills and pygmy shags in the Neusiedler See area in 2014. In: Ornithological monitoring in the Neusiedler See – Seewinkel National Park. Report on the year 2014, pp. 41–43l. PDF

- ^ R. Winkler: Avifauna of Switzerland. Der Ornithologische Beobachter, Supplement 10, 1999: pp. 22-23

- ↑ Swiss Ornithological Institute Sempach Factsheet - Cormorant and birds of Switzerland - Cormorant

- ↑ Keller, V. & Müller, C. 2015. Kormoranbruten Schweiz 2014 ( Memento of the original from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Final report of the Network Fish Decline Switzerland project - chap. 5.10

- ↑ The Cormorant at Birdlife International

- ↑ Expert opinion on behalf of the Thuringian Ministry of Agriculture, Nature Conservation and Environment The stock situation of grayling (Thymallus thymallus) in Thuringia, 2005, there pages 7-48, with detailed literature and references

- ↑ Michael Möhlenkamp, Agricultural weekly newspaper Westphalia-Lippe, 09/2014, Der Kormorankonflikt , pages 53, 54

- ^ Landesfischereiverband Baden-Württemberg: Damage caused by the cormorant

- ↑ Press release European Parliament of December 8, 2008

- ↑ Cormorant Ordinance of the State of Saxony-Anhalt of September 15, 2014, GVBl. P. 432 ( Page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 218 KB)

- ↑ Kluxen, G. (2013): Evaluation of Kormoranmanagements im Aischgrund. - ANLiegen Natur 35 (2): 71–75, running. PDF 0.3 MB

- ↑ Austrian Board of Trustees for Fisheries and Water Protection: [3]

- ↑ Lippischer Fischereiverein: [4]

- ↑ Stephan Börnecke: “For want of evidence.” In: Natur 5/17, p. 56 f.

- ↑ Josef H. Reicholf: Do overwintering cormorants (Phalacrocorax carbo) eat abnormally high amounts of fish?

- ↑ Josef H. Reicholf: My life for nature. On the trail of ecology and evolution. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt / M. 2018, p. 555

- ↑ a b Marcus Beike: The history of the cormorant fishery in Europe . The Bird World 133: 1–21.

- ^ Marcus Beike: The history of cormorant fishing in Europe . Archived copy ( memento of the original from March 5, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Helmut Opitz: The cormorant as "bird of the year" . Der Falke, special issue 2010: 40–41