crane

| crane | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Crane ( grus grus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Grus grus | ||||||||||||

| ( Linnaeus , 1758) |

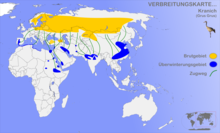

The crane ( Grus grus ), also Gray Crane or Eurasian Crane , is a representative of the family of cranes (Gruidae). In Europe it is largely the only crane species; Only from the Black Sea region does the Jungfernkranich begin to spread . Cranes inhabit swamp and moorlands in large parts of northern and eastern Europe , but also some areas in northern Asia . They consume both animal and vegetable food all year round. The population has increased significantly in the last few decades, so that the species is currently not endangered.

The beauty of the cranes, their spectacular courtship dances and their easily observable procession have fascinated people in the past. In Greek mythology , the crane was assigned to Apollo , Demeter and Hermes . He was a symbol of vigilance and wisdom and was considered the "bird of luck". In heraldry , the crane is the symbol of caution and sleepless vigilance. In poetry the crane symbolizes the sublime in nature.

description

Appearance

Like all members of the genus Grus , the crane was traditionally classified as a " walking bird " because of its size, long legs and long neck . Characteristic are the black and white head and neck markings and the featherless red headstock. The wedge-shaped, slender beak is over ten centimeters long. The plumage has refrained from the head a light gray color in many shades. Birds that are almost white and very dark are very rare. The tail and the hand and arm wings are black. The humeral feathers vary in color from gray to black and hang over the tail of adult birds as a "train". During the breeding season, the shoulder and back area is colored light to dark brown with peat earth. As a special feature in nature, the individuals in the crane are divided into two different eye colors, red or yellow, without any connection to other features. The sexes are difficult to distinguish externally. However, males are on average slightly larger than females. The former weigh five to seven kilograms, the latter five to six. The crane reaches a height of 110 to 130 cm. The wingspan is about 220 to 245 cm.

Fledglings show a uniform light gray-brown color and do not yet have a train. The head is a monochrome, reddish sand color without black and white markings, the eyes are still very dark. In one-year-old young birds, a faint light-dark markings develop on the head and neck. They are even lighter than adult birds. Biennial fledglings resemble adult birds apart from a less pronounced train.

The moulting of the small plumage takes place annually from spring to autumn. Adult birds molt in a three to four year cycle.

flight

Before taking off, the head and neck are usually arched ten to twenty seconds in the direction of flight in order to synchronize the take-off with each other using voice signals. After a few quick steps, the cranes push themselves off the ground and fly with their necks stretched out. Greater distances are covered in gliding, short distances also in rowing flight . Cranes are persistent fliers and can cover up to 2000 kilometers non-stop, with shorter daily stages of 10 to 100 km being the rule. In flight they reach an average speed of 45 to 65 km / h.

voice

Cranes have different calls that are important for social behavior. The loud trumpet-like call (here flight and warning calls) is made possible by the resonance space of the 100 to 130 cm long windpipe. In the case of a “ duet call ”, a series of calls is followed by a sequence of tones coordinated with it. Both males and females can initiate the sequence of duets through it. Both point their head and beak upwards, tilt their necks backwards and lift their wings. They stand close together and move slowly next to each other during the series of calls. The duet call sounds when excited at assembly and resting places, most often during the breeding season. It can be used for individual characterization and recognition through frequency analysis ( sonography ).

Another loud call is the warning call, which is emitted by a couple or more birds when there is danger. The double call is initiated by calling a partner with his neck stretched out. The male follows with a lower sound or the female with a higher sound. It can often be heard over long distances when there are disturbances in breeding areas. A searching individual animal or group utters the loud contact call, especially with limited visual contact or with a stronger train atmosphere. He also announces the upcoming withdrawal.

The contact call of the chicks is expressed in a gently trilling sound. When excited, they emit a loud, whistling beep. The begging call consists of a plaintive beep. The family members communicate via trilling contact calls. To warn the boys, calls made of sharp and vowelless tones are uttered both on the ground and in the air.

distribution and habitat

The breeding areas of the crane are in northeastern Europe and in northern Asia . The rivers Weser and Aller mark the western, the 51st degree of latitude the southern limit of the distribution area. Cranes are easy to spot on the Brandenburg lakes and the Mecklenburg Lake District. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the loss of biotopes has caused the southern border of the European and Central Asian area to shift 300 km to 400 km to the north. The loss of isolated breeding areas is due to the drainage and cultivation of wetlands, egg collecting and hunting, as well as ecological conditions (lack of water, drought). However, repopulation is possible under today's improved protection conditions.

The crane colonizes all of Scandinavia and Finland . In Central Europe it can be found in Poland and the Czech Republic as well as in the north and east of Germany . In Eastern Europe, the crane is common in the Baltic states of Lithuania , Latvia and Estonia , in Belarus and in northern Ukraine . Decades ago the south of Georgia , Armenia , the southern Ukraine and the north-east bank of the Aral Sea were still breeding areas. The crane sporadically breeds in England , France , Italy and the Netherlands . It used to be common in Romania , Yugoslavia , Albania , Bulgaria and Greece . Eastern Siberia and the Far East are still sparsely populated. In Turkey and around the Himalayas in Bhutan and Tibet stable, independent populations are found. However, its distribution in northeast China is decreasing. In the past, cranes were also widespread in Kashmir and the far north of India.

Its preferred habitats are wetlands in the lowlands, such as low and high moors , swamp forests , lake edges , wet meadows and swamp areas . In order to search for food, the animals find themselves on extensively managed agricultural crops such as meadows and fields, field borders, hedges and lake shores. To take a break, they use wide, open areas such as fields with stubble. Waters with low water levels, which offer protection from enemies, are mainly sought out as sleeping places.

hikes

There are several migration routes in Europe that have been explored since the early 19th century. Exact knowledge is available for the Western European train route and the northern part of the Baltic-Hungarian route.

The Western European train route

Cranes from Sweden, Norway and perhaps also from northern Finland migrate through Sweden in a north-south direction, with stronger migratory concentrations having developed in the western and eastern parts of the country. From mid-August onwards, larger groups of western migrants will reach the German mainland between the mouth of the Oder and the Darß . The number of birds that prefer to rest on the island of Rügen and near Groß Mohrdorf reaches its peak between mid and late October. Ostzieher partially rested on Öland , in order to then cross the Baltic Sea towards Rügen, Poland and Estonia. The departure of Scandinavian cranes takes place between mid-August and mid-October, occasionally also in November.

From mid-September, Germany will be approached from both the north and the east with a break between the Baltic Sea coast and Lusatia . Since the mid-1980s, there has been a large increase in east-west migration inland, so that the highest numbers since 1996 at the large rest areas in Silesia , in the Toruń- Eberswalder Urstromtal , in Linum north of Berlin , in Dahmeland and Lusatia of coastal regions. An important gathering point is the Kelbra dam south of the Harz Mountains , where up to 17,000 animals can be observed. The high point of the east-west passage is in the second half of October and first half of November, with larger groups of migrants from the east still moving in until mid-December and, in unfavorable weather conditions, even into January. The train will continue in a south-westerly direction, combining the northern and eastern train contingents as well as the flights from the various rest areas west of the Rhine .

After the withdrawal from the East German rest areas, the train groups mostly move westwards across the Rhine-Main area to France. There the train route runs diagonally through the country. The major resting areas are near Orléans and the Champagne humide as well as in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region . It is common to cross the western Pyrenees in the province of Navarre and the eastern Basque Country before dawn begins. For more than a decade, France has also been used intensively for wintering.

In northern Spain there are only a few places to rest. Migratory concentrations form at the Laguna de Gallocanta in the provinces of Zaragoza and Teruel . The first birds appear in October, in the second half of which there is a stronger influx, which peaks between late November and mid-December. The wintering areas are Extremadura and Andalusia as well as about 58 other places. A small part of the population moves even further to North Africa. Withdrawal begins in late January and peaks between late February and early March. The migration on the Western European route increased from a maximum of 40,000 cranes at the beginning of the 1980s to over 60,000 birds in 1990 to around 150,000 cranes in 2001.

The Baltic-Hungarian train route

Taking along the populations from the Baltic States, Belarus as well as the Polish East and Ukrainian West, the train starts in Finland and northwestern Russia in autumn and then heads south to the Hungarian Plain with its large resting places. In Finland, the highest migratory concentrations are to be found west and east of Helsinki .

After union with the major north-west Russian flights, southern and south-westerly routes dominate over Latvia and Lithuania. The train size increases continuously in the rest areas from northeast to southwest. These flights rarely rest in Finland, but mostly between the beginning of September and mid-October at more than 40 beds in Estonia. Then the birds migrating southwards cross the Lower Beskids and pass through the forests of the Forest Carpathians into eastern Slovakia . While these migratory groups fly over higher mountain ranges to eastern Hungary, smaller contingents are taking the route through eastern Romania. From mid-October to the beginning of November, the major flights are concentrated in the rest areas, especially at the Kardoskut Salt Lake and in the Hortobágy National Park .

South of Hungary, the migration route divides into an eastern and a western route (Mediterranean train route). On the latter route, the western Balkans are first crossed in order to get from the Albanian Adriatic coast via Sicily and Calabria to Tunisia . It is said to have occasionally been overwintered on the Aeolian Islands and Sardinia . While 20,000 birds are known to hibernate from Tunisia, the further route of the 50,000 east migrants is largely unknown. It is believed, however, that a small part overwinters in Israel and a larger part remains in eastern Africa after a rest in Cyprus . The western migrants move on via Egypt along the Nile to rest at oases there or move on towards the Red Sea and Israel, while the east migrants of this route and the Russian-Pontic migration route overfly Turkey . The total number of birds on the Baltic-Hungarian route is currently (1989) estimated at 80,000 to 90,000.

Further migration routes

Large groups of migrants migrate from the Russian, Belarusian, northern Ukrainian as well as from the Siberian and Kazakh breeding areas on several migration routes in southern, southwestern and southeastern directions. In the Eastern European region, a Russian-Pontic and a Volga- Iranian migration route are distinguished. Further east there is a West Siberian-Kazakh-Indian route, which brings the cranes from West Siberia and Central Kazakhstan via Central Asia, bypassing the great mountains of Central Asia to Pakistan and India . There is also an East Siberian-Chinese train route from Central Siberia and the Transbaikal via Mongolia to Central and Southeast China. Finally, a Far East-Chinese migration route of the Far Eastern populations of Russia and China runs across the lowlands of northeast China to the wintering areas in southeast China. Small groups also overwinter in Korea and Vietnam .

Food and subsistence

Cranes eat both animal and vegetable food all year round. The food consists of small mammals , reptiles , small fish , frogs , snails , worms , insects and their larvae. It also includes corn , barley , wheat and oat kernels , sunflower seeds , peas , beans , peanuts , olives , berries , acorns , vegetables , potatoes , plant roots, sprouts and stalks .

During the spring break, the crane feeds mainly on seeds. In order to replenish the energy reserves, he needs more than 80 percent of the activity duration for food intake of up to 300 grams per day. In early summer, the diet also consists of insects and small vertebrates . Once the young birds have reached the age of several weeks, larger animals such as mice also enrich the offer. In late summer and autumn, foraging for food takes up about 40 to 60 percent of the duration of the activity. Now crop residues and new seeds as well as insects form the main component of the diet. In the wintering area, cranes feed on the fruits of the hard oak and cork oak as well as on sunflower seeds.

In meadows and pastures, foraging is concentrated on insects, worms and rodents . Here, cranes walk across large areas with far-reaching steps. They read insects sitting on grass and herbs in a targeted and jerky way with their beak and lay worms and larvae free by digging. To do this, they prick plant-free areas in the ground with their bills almost closed. In the ground they open their beak slightly and move it sideways. If the soil is thicker, loosen it beforehand by repeatedly piercing it. On the seedbed, cranes first read the grains lying on the surface. Rummaging also exposes additional seeds. Corn kernels are also eaten by the cob. By pulling the head up, the grains can be swallowed. Vertebrates are stabbed with the beak.

Reproduction

The crane usually lives monogamous for life , but the latest research shows that changing partners is possible and even more frequent than was previously known. The crane reproduces for the first time when it is three to five years old, but can attach itself to a partner as early as two years on its spring break. However, it is not yet clear whether these pairs will later occupy breeding grounds together. (In one single case so far, that of couple # 6 in the Duvenstedter Brook nature reserve , Hamburg, it was shown that a young couple later occupied a territory.)

Breeding grounds and breeding grounds

Ancestral breeding pairs take possession of territories regionally around the same time. The area must offer an adequate supply of food as well as peace and security. In Germany, 60 to 70 percent of birds prefer to use forests or forest edges. The open field is increasingly being used for breeding (20 to 30 percent), and the banks of the lake also play a role (10 to 20 percent). If there is less food available, the territories are larger. Investigations on young birds equipped with transmitters revealed that cranes use an area of more than 135 hectares in some cases until the young have fledged.

Cranes are ground breeders. The breeding site forms the center of the area and is located on the ground in moist, often swampy terrain. In the case of very small breeding sites, it is usually not possible for the birds to create their nests behind a cover. The water used can be smaller than one hectare to larger than ten hectares, but the decisive factor is a water depth of 30 to 60 cm. If wading to the nest is not possible, cranes are prepared to swim or fly as an exception. A good view of the surroundings is fundamentally important to the breeding bird. If the water level is too low or it is dry, no nests are built, but the territories are still occupied.

To build nests, reeds , reeds , rushes , sedge and other plants within a ten meter radius are torn off with the beak. Both partners throw the nesting materials sideways or over their backs towards the nest and then gradually bring them to the nest. The nest can have a diameter of over a meter, the platform is usually 10 to 20 cm above the water surface. Since the nest collapses during the breeding season, it is constantly being built during the breeding period.

Courtship and mating

The “crane dance” takes place all year round, but is most intense as a courtship ritual in spring. It takes place in the early dawn in nearby open spaces. In the course of March, the frequency and severity of this behavior increases, which then culminates in the mating. It usually ends with nest building and egg laying.

While dancing, males and females jump around with outspread wings and let their loud trumpets be heard. But bragging rights, running in straight lines and curves, kinking the legs, jumping and throwing up parts of plants are also part of the ritual. By straightening the upper body, bending the wings and cooing noises, the female finally prompts the male to jump up and thus to mate. Once the pedal stroke is completed, the male usually jumps forward over the head of the female. This is followed by duet calls from the partners and then usually a cleaning phase. The duet can be heard throughout the breeding season and later as a sign of solidarity.

Egg laying and brood

In Central Europe, females begin breeding three to six weeks after their arrival. They usually lay two eggs two to three days apart from March to mid-April. These have a longitudinally oval shape with a round and a pointed oval pole. They vary considerably in shape, size and color. The basic color is light brown with a tendency towards greenish, reddish and reddish brown. Coarse brown spots are usually irregularly distributed and often condensed at the blunt pole. The size varies between 57 and 66 mm in width and between 88 mm and 110 mm in length. The weight averages 185 g. The clutch is incubated alternately by both partners for 29 to 31 days, so that one of them can go looking for food. The brood is started with the first egg, so that the young hatch every day or two.

On average, incubation takes between 1.6 hours and 4.5 hours, so that, including the night, the respective incubation period is over twelve hours or more. The brood detachments take place at irregular intervals, but increase from the start of hatching until the young are led away. During the hatching period, the releasing person often brings plant material to the nest. A breeding break is initiated at regular intervals by getting up or occasionally leaving the nest, the frequency of which depends on factors such as the incubation level, outside temperatures, precipitation and time of day. Before the crane sits down in the clutch again to breed, it turns the eggs with its beak.

In the crane there are clutch losses of 20 to 30 percent. These turn out to be particularly high if the nesting site falls dry during the breeding phase or after hatching, as the nest can easily be reached by predators . In addition to the water level, particularly cold weather, disturbances, lack of food and predators are responsible for losses.

Help with hatching

A specialty occurring with cranes is the obstetrics for their own chicks. As soon as the young birds try to break through the egg, the parent birds kick the affected egg with their claws to make it easier for the chick to get out. However, the step of the adult birds is only so strong that it damages the shell of the clutch and does not injure the offspring. This behavior has been documented and observed several times, but it has not yet been properly researched, which means that only a few film recordings exist.

Development of the young

The first sounds of the chicks before hatching, but at the latest when the egg opens, change the behavior of the adult birds. They are now more nervous and often stay near the nest.

The young can safely stand and walk approximately 24 hours after hatching. Those who flee the nest are led away from the nest after 30 hours at the latest. Both adult birds take care of feeding and leading the young equally. These initially have a cinnamon-brown down plumage. Their hatching weight is between 120 g and 150 g. In the first weeks of life , the adult birds give the chicks insects , larvae, worms and snails with their bills until they can search for food independently.

The yolk supply of the hatched young birds is sufficient for two days. Nevertheless, despite the additional feeding of small food and egg shell remains, they initially lose weight. In the first few days, the boys are taken on small stretches in the vicinity. In the first two weeks, fledglings left alone in the nest often attack each other with beaked blows, with the older chick occasionally trying to force the younger out of the nest. After the aggression has subsided, the family stays in the forest or in fields and meadows , even if they continue to spend the night in or near the nest. If the water level has dropped too much, a sleeping nest will be built in a suitable place. After about ten weeks the young are able to fly and are almost as big as the adult birds.

In most cases, communication takes place via a quiet contact coo. Loud calls are only used in the vicinity of the nest in the event of strong disturbances in order to warn the young even from greater distances. In case of danger, inferior attackers are attacked with bills and flaps of their wings and driven away. Superior opponents like humans are distracted by " enticing ". One adult bird pretends to be sick by moving with a stretched neck and hanging, spread wings, often limping away from the family, while the other leads the young away and makes them crouch by shouting a warning.

Especially in September, but also from the beginning of August or the beginning of October, the families join the non-breeders at the assembly points. Only a few breeding pairs, most of which live on the sparsely populated peripheral areas, remain in their breeding grounds until they move away.

Life expectancy is up to 40 years in captivity; it is much lower in wild animals.

behavior

The species usually starts its activity in the first twilight. Many hours a day are spent looking for food, with the activity peaks in the late morning and early afternoon. In between there are periods of rest.

The crane lives in three different social forms. In the summer, breeding pairs live alone in their territories, while non-breeders form groups. Cranes spend most of the year in a community of conspecifics of different ages at assembly and resting places. In spring and autumn they form migratory flocks of up to a few thousand birds.

The intraspecific behavior regulates the complex relationships between individuals. The red, featherless plate on the top of the head, which swells when aroused a lot, is of particular importance. The dance outside the breeding season also has this function in certain situations. In autumn and especially in spring, individual birds or larger groups dance while gathering and resting.

Territorial behavior

To defend their territory against intruders, the crane first threatens the enemy and then attacks him if he does not allow himself to be intimidated. This is usually initially the responsibility of the male, but it can also be done by the whole family.

Birds of the same rank threaten each other by facing each other with plumage drawn and necks outstretched so that their beaks almost touch. After a short pause, they chop forwards or upwards until the loser backs away. This is pursued continuously and on the fly until it has exceeded the territorial limit. In tougher conflicts, the birds can jump up and throw their legs forward to kick the opponent. By ritualizing further intimidating behaviors, the risk of injury is reduced and energy is saved. If a crane is in an internal conflict between attack and retreat, it can lead to jumping over actions such as the apparent cleaning or pecking. In rare cases, one of the rivals buckles in the intertarsal joints , lying on the ground with his neck outstretched and spreading his wings. This behavior also occurs in breeding birds in the conflict between brood care and the flight reflex.

Non-breeder groups

One to four-year-old non-breeders usually return to their breeding home for at least the first year. They arrive two to four weeks apart after the breeding pairs. There they stay in small and large groups, which are often together with migrants on their way north and east. After they have moved on, young and older non-breeding cranes are mostly in the closer and wider area of their breeding home. Some of them stay in the resting areas of the migration path until they are collected in autumn, so that they are distributed over the entire distribution area.

Non-breeders live in variable communal groups with no hierarchy . They are not very vocal and usually behave inconspicuously, sometimes clandestinely. This manifests itself in the frequent change of daytime and sleeping places. Studies show that individual individuals are not tied to one place. Oversummerers withdraw in small groups to moult.

Small groups of non-breeders explore previously unoccupied areas and can be the first vanguard for resettlement. Therefore, both breeding loyalty and the settlement of new areas contribute to the stabilization and spread of the population as well as to genetic mixing.

After looking for food in meadows and pastures from April to July, they arrive at assembly points from late July to early August - before the arrival of unsuccessful breeding pairs.

Assembly and resting places

A local crane population likely gathers each year at the same gathering points, which are located in all high-density breeding areas. The resting places consist of the sleeping areas and the up to 20 km long catchment area with the food areas. The sleeping places form the basis of the assembly point. Two thirds of all rest areas therefore have two to four berths, which are sometimes approached at the same time, but often also one after the other.

There is a fixed daily rhythm at assembly and rest areas. After the cranes have slept in the shallow water at night, they call for contact with the first dawn and shake their plumage free. They fly off around sunrise or harvest areas such as stubble fields during rest periods. The duration of the departure is usually shorter than that of the evening flight. Foggy days or dangers delay the start. Between late afternoon and the onset of darkness, they arrive at pre-assembly or intermediate landing areas, which are located on arable and short-grass grassland areas in the vicinity of the sleeping places and make up part of the sleeping area. The number of birds increases during the afternoon and can reach sizes from 100 to 40,000 cranes. While shouting loudly, they gradually fly or stride, usually in groups, to the sleeping place only at dusk.

Being together in groups minimizes the effort required for securing and allows less experienced young birds to make optimal use of the time available for feeding.

Wintering groups

In the wintering areas, some of the families separate themselves and show a clear connection to a certain territory that is visited every year and defended against conspecifics. The daily rhythm corresponds to that of the assembly and rest areas. In January and December, the days are used to the full, so that the last flights can only take place when the moon is full and the sky is clear. In February, the approach usually ends at dusk. The departure takes place after sunrise.

Migratory behavior

One to two days before the start of the mass withdrawal or another move, the birds show restless behavior. They shout and dance a lot, have a disturbed rhythm during the evening overflight at the sleeping places and are excited at night. The prerequisites for the start of the train are tail and cross winds, food situation and temperature changes.

The crane procession is made up of groups of couples or small families who gather in their thousands at well-known wintering and resting places. Cranes fly in wedges, unequal angles or oblique rows, so that air resistance is reduced and contact within the group is ensured. While dragging, they communicate with each other using sounds that are particularly frequent at night or in poor visibility. The film attached below shows the formation and sounds of cranes migrating south near Hollerath in the Eifel on a November day; an annual, recurring spectacle that goes on for hours in which thousands of cranes can be counted.

As a rule, the migration is completed in stages, as the birds adapt to the weather conditions and make stops of different lengths along the way.

While a few decades ago the cranes did not arrive in the breeding areas of Central Europe until March, they now return in February. Since then, both a late withdrawal in autumn and real hibernation and hibernation attempts have been detected. Due to this changed tensile behavior, lost scrims can be replaced by additional scrims.

Behavior towards other animals

The behavior towards alien animals is extremely varied. Roe deer and red deer usually do not worry the birds. The escape distance in the event of a fault is 250 m to 300 m and is generally greater in an unknown environment.

While predators pose a greater danger in the breeding area, they are usually neglected in groups. Sometimes a small group will band together in a mock attack or dance against mammals . As a particular danger, birds of prey are observed more closely and chased away if possible. Breeding pairs generally attack foxes and wild boars and often chase them away. The same applies to nest robbers such as the common raven and other corvids , who still steal eggs when cranes leave the nest due to disturbances.

If a sea eagle attacks on the roost or on grazing areas, the group flies up or quickly forms a castle-like formation and at the same time gives warning calls. When the eagle plunges down, the cranes point their beaks at it like spearheads, attacked birds often throw themselves on their backs in the air and hit the attacker with their feet. While sea eagles usually only prey on sick and weak animals, golden eagles are also very successful with healthy cranes.

Systematics

DNA studies show that the Eurasian crane Grus grus is most closely related to the whooping crane ( Grus americana ). He is also close to the black-necked crane ( Grus monachus ) and the black-necked crane ( Grus nigricollis ) as well as the red-crowned crane ( Grus japonensis ).

In the past, the crane Grus grus was divided into two subspecies, the Grus g. grus ("Western crane") and Grus g. lilfordi ("Lilford crane"). The latter was considered a smaller, lighter variant, whose distribution area east of the Urals , limited by Mongolia and the Kolyma Mountains, was assumed. This classification is no longer used because no clear distinguishing features can be established. The variations are based only on differences in the behavior of feather coloring with a substrate.

Existence and endangerment

Inventory development

A distinction is made between seven main populations of the crane:

| population | Duration | trend | IUCN protection status |

| Western Europe | 60-70,000 | Increasing strongly | Not at risk (LC) |

| Eastern Europe | 60,000 | Stable to increasing | Not at risk (LC) |

| European Russia | about 35,000 | Decreasing | Vulnerable A1a, c, d |

| Turkey | 200-500 | Decreasing | Data deficit |

| Western Siberia | about 55,000 | Decreasing | Warning list (NT) |

| Eastern Siberia / Northern China | 5,000 | Decreasing | Vulnerable A1 C1 |

| Tibetan plateau | 1,000? | Probably stable | Data deficit |

| total | 220-250,000 | Increasing overall, but decreasing locally | Not at risk (LC), Appendix II |

The inventory figures in the table should be viewed as a tentative estimate from 1995. Only in Europe and the center of European Russia is the data regularly and reliably determined and recorded. The trends are only partially understandable. The total population is likely to increase despite local decreases. This mainly affects the central and eastern distribution area. The species is also listed in Appendix I of the EC Bird Protection Directive 79/409 / EEC, in Appendix II of the Bonn Convention and in Appendix II of the Bern Convention .

The populations of Western and Eastern Europe together make up more than 50 percent of the world's population. According to the IUCN , these are relatively small with more than 110,000 pairs and decreased significantly between 1970 and 1990. Although the species has basically increased largely between 1990 and 2000 and shows increasing or stable trends in most of the distribution areas in Europe, the population is not yet considered to have recovered because it has not yet reached the stage before the decline. As a consequence, it is temporarily listed as depleted in Europe.

According to the IUCN, the worldwide distribution area covers approximately 15,400,000 km². In contrast to the table above, the population is estimated at around 360,000 to 370,000 individuals in 2009. Therefore the species is classified as not endangered (LC).

The crane has been at home in Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania since 1991. In 2019, 80,000 cranes were counted on the Darß alone and 9,000 on the Großer Schwerin , more than ever before. 300,000 cranes cross the country on the autumn route from the Baltic Sea to France. With the rich food supply, more and more people have been wintering in northeastern Germany since 2007. 60% of the cranes leave Europe, in Germany and France around 40% stay.

Hazard and protection

The main threat to crane populations comes from habitat destruction and pruning. The loss of wetlands is associated with drainage, dam construction, intensification of agriculture and urbanization, as well as wildfires and floods. However, disturbances in the breeding areas and direct pursuit as well as electrical overhead lines represent dangers.

The International Crane Foundation (ICF) works on crane research, the protection of wetlands, the exploration of occurrences and the protection, reproduction and reintroduction of all threatened crane species. The three main centers of training, reproduction and management publish the ICF-Bugle information brochure for members every quarter . The ICF also organizes symposia and conferences. The European Crane Working Group coordinates the protection of the crane in Europe, especially in some national working groups. It is supported by Lufthansa , some ministries, NABU and WWF . At the European Crane Workshop , information and experiences are exchanged and the protection strategies of the countries are approximated.

As part of an international project, captured young birds are ringed according to a country code and, in some cases, equipped with small radio transmitters . Thus cranes not by dogs, pistols , fireworks are sold, vehicles or other means of farmers, preventive Ablenkfütterungen held various variants. The offering of chopped maize from current production is particularly successful.

According to § 7 Paragraph 2 No. 14 lit. a) BNatSchG a strictly protected species and listed in Appendix I of the Birds Directive . It was bird of the year 1978. In Germany it has been classified as not endangered since 1998. In order to protect the crane, the Federal Nature Conservation Act prohibits both entering the breeding areas and looking for feeding and gathering places. Exceptions for nature conservation purposes can be granted by the responsible authorities.

The crane is protected all over Europe, in the successor states of the former Soviet Union , in China, India and Iran. In the countries along the Eastern European and Asian migration routes, however, forestry, agricultural and hunting activities are permitted in the vicinity of the crane's habitats. In the countries of the Western European migration route, however, there are clear legal provisions and protected habitats.

Crane and man

Cranes in culture

The beauty of the cranes and their spectacular courtship dances have fascinated people in the past.

Mythology and cult

In Egyptian mythology , the crane was known as the "sun bird". It was used both as an offering to the gods and as a feeding bird. In the hieroglyphs , his figure stands for the letter "B".

In Greek mythology , the crane was assigned to both Apollo , the god of the sun and Demeter , the earth and fertility goddess, and Hermes as the messenger of spring and light. The augurs (priests) in Greece read from the flight formations of the cranes. In addition, cranes were considered a symbol of vigilance and wisdom.

According to Homer's Iliad , an army of man-eating cranes is said to have moved south to hunt the pygmies in the Nile Marshes . In addition, Homer mentions the "dance of Ariadne", which was found after Pausanias in Knossos on Crete. The Greek Theseus is said to have introduced a dance called geranos on the island of Delos . He had this dance, modeled on the corridors of the maze of Crete, from his lover, the Cretan king's daughter Ariadne , who in turn had learned it from the famous craftsman and inventor Daidalos . Aristotle describes him as the bird that is extremely vigilant and moves "from the Scythian plains into the swamps above Egypt".

The Celtic god Ogma is said to have invented the Ogham script after he had observed the flight of the cranes, which were considered the keepers of the secret of this script. In Ireland , peasants asked the god Manannan , who carried a crane skin bag with the treasures of the sea, good seeds and the seafarers a safe journey. The Agrippin people mentioned in the legend of Duke Ernst consisted of a hybrid of man and crane. They harassed a dwarf people until Ernst could free them from them. The name "bird of happiness" is derived in Sweden from the arrival of the crane as a sign of spring, which introduces warmth, light and abundance of food.

In the old Chinese Empire , the crane ( Chinese 鶴 / 鹤 , Pinyin hè ) was a symbol of longevity , wisdom, old age and the relationship between father and son. In addition, in Chinese mythology it was known as the “sky crane ” or “blessed crane ”, as it was assumed that Taoist priests turned into a feathered crane after their death or that the souls of the deceased were carried to heaven on the back of cranes. In the Qing Dynasty , the crane was the badge of civil servants of the first rank.

In Japan , the crane is a symbol of luck and longevity. According to Japanese popular belief, whoever folds 1,000 origami cranes ( 千 羽 鶴 , senbazuru ) gets a wish from the gods. The oldest surviving publication on this motif and on origami in general is the Senbazuru Orikata ( 千 羽 鶴 折 形 ) from 1797. Even today, a folded paper crane is presented on special occasions, such as weddings or birthdays. Since the death of the atomic bomb victim Sadako Sasaki , who fought against her radiation-induced leukemia by folding origami cranes , origami cranes have also been a symbol of the peace movement and the resistance to nuclear weapons .

In Hokkaido , the women of the Ainu also perform a crane dance, just as in Korea a crane dance has been performed in the courtyard of the Tongdosa Temple since the Silla dynasty . The Central African queen of the pygmies , Gerana , is said to have been transformed into a crane, according to ancient stories, because she thought she was more admirable than the goddesses. The Aztecs originated according to legend from the region Aztlán , which meant "near the cranes." In superstition it is said that cranes circling around the house in the swarm announce that they will soon have offspring.

heraldry

In heraldry, the crane is the symbol of caution and sleepless vigilance. In Greek mythology , the flying crane carries stones in its beak so that it does not betray itself through its own calls over the Taurus Mountains and fall into the clutches of the eagles. The crane has gained further meanings in the Roman culture. It was seen as a symbol of “Prudentia”, sensible and wise action, “Perseverantia”, perseverance, and “Custodia”, the diligence of action. From the "Vigilantia", the moral and military vigilance, the "Grus vigilans" arose. He holds up a stone with his claw so that if he falls asleep he would be woken up by the sound of falling. You can find this motif on many emblems , coats of arms and insignia , but also on houses and castles . So it says in the gable song of the crane house in Otterndorf :

The crane holds the stone to

fight off sleep.

He who surrenders to sleep

never gets good and honorable.

Church father Ambrose uses this image as a parable for the fear of God to protect against sin and the work of the devil. He also compares the falling of the stone with the call of the church (bells ringing). He also believes that people should imitate the cranes by supporting the strong against the weak.

Fairy tales, fables and literature

In old folk tales and traditions, the crane, which is usually associated with positive characteristics, appears as a herald of births and weddings, but also of war and death. The ancient Israelite prophet Jeremiah uses the migratory behavior of this bird as a parable (time of repentance) in the Bible . In fables it is usually used to show human injustice and ingratitude.

The Yakut story The Crane Feather is about a crane who turns into a beautiful girl in order to marry a man of man. When one day he finds his stripped plumage again, he swings away so that he stands for the fleetingness of summer and love. The Russian fairy tale heron and crane and the Finnish fox and crane , in which the fox wants to learn to fly from him, also deal with this bird.

The Aesopian fable of the wolf and crane (or Phaedrus: the wolf and the crane ) is also unfair. Here the crane frees the wolf from the bone that has got stuck in its throat, but is cheated of its wages.

The Meistersinger Hans Sachs shows in the fable poem The peacock with the crane (1537), a dispute between Peacock and Crane to make it clear that everyone will find his gifts and to use, without the other to be despised. In the German fable of the fox and crane , both invite each other to a meal that only they can eat themselves. Even Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , this issue is dedicated in a poem. In Felix Dahn's ballad Walther von der Vogelweide, 03. The crane , the crane symbolizes the Christian savior who accompanies the crusaders to the Holy Land in Jerusalem and sacrifices himself to save human life.

In poetry the crane is used symbolically for something “ sublime ” in nature. Wilhelm Busch's The Clever Crane alludes to the watchful bird that carries the stone. Friedrich Schiller inspired the story of the cranes, whose appearance betrayed the murderers of the poet Ibykus, to the famous ballad The Cranes of Ibykus . Goethe lets the protagonist complain in Faust (Before the Gate) :

"And over areas, over lakes

The crane strives for home."

Ewald von Kleist's poem The Paralyzed Crane speaks of a specimen that cannot move south and has to assert itself against its mockers in winter and endure its suffering. In Theodor Fontane's poem The crane is told as a crane with clipped wings longingly tried to move his peers and is ridiculed by a vain effort from the chickens. The poems Der Kranich by Nikolaus Lenau and Die Kraniche by NM Rubcow also have this bird as their theme.

Bertolt Brecht uses flying cranes as a symbol for love in his poem Die Liebenden . It begins:

“See those cranes in a wide arc!

The clouds that were attached

to them were already moving with them when they flew

from one life to another "

In Ernst Wiechert's The Jeromin Children , the crane describes how the egg robber Gogun steals the clutches and young birds in order to sell them to landowners. In Viktor S. Rozow's drama The Eternal Lovers , these birds are used as a motif for the death of the protagonist Boris. In Tschingis Aitmatov's novella Early Cranes , cranes appear as heralds of the approaching spring, love and joie de vivre, but also as a warning against war, alienation and division. Even Selma Lagerlof mentioned the Crane in The Wonderful Adventures of Nils in a chapter (The great crane dance on Kullaberg) . In the animal stories of Pentti Haanpää the crane is humanized and individualized.

Music, art and film

Bertolt Brecht's poem “ The Lovers ” is a duet part of the opera Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny .

The crane can be found in the fine arts from the earliest times to the present day. It is a motif on blackboards and murals as well as on miniatures and illustrations . There are also craft and sculptural works made of textiles, ceramics , wood , stone , bronze , precious metals and other materials. This bird is particularly popular in Asia .

In Christian art, the mosaic of the Church of San Marco in Venice depicts cranes waiting with other birds to enter Noah's Ark . Albrecht Dürer shows Justitia with the stone-bearing crane at her side in an engraving .

In the Armenian culture the crane ( Armenian spielt - krunk ) plays a major role. In a famous song by Komitas Vardapet, for example, he is addressed as the bearer of news from his distant homeland, symbolizing the fate of displacement that the Armenian people have often suffered in their history.

In the film The Cranes Drag the Russian director Michail Kalatosow , flying cranes form the motif when it comes to the death of the protagonist Boris.

By Juliane Werding there is the hit The last crane from Angerburger Moor .

The musician Bosse wrote and sang the song Kraniche , which appeared on the album of the same name in 2013 and describes the observation of cranes at the end of September.

Others

The flying crane is a trademark of modern means of transport. So carry him Automobile of the Hispano-Suiza , but also airlines such as Japan Airlines , Air Uganda and Xiamen Air China. The German Lufthansa used him since 1926 as a logo, which in 1918 by Otto Firle in Berlin was created. The Polish airline Polskie Linie Lotnicze LOT has also had a stylized crane as its trademark since 1931.

The operations department of the Austrian police , which was founded at Vienna-Schwechat airport on the occasion of the terrorist attack that took place there on December 27, 1985, also bears the name "Operations Department Crane". The name was chosen because of the bird's particular vigilance and in association with flight.

Dealing with the real animal

The crane as prey

The rock carvings in Spanish caves as well as in Sweden and the finds of bones in Neolithic settlements indicate that cranes were hunted in prehistoric times. Interestingly, bones from Roman times found in Hungary are about 10 to 20 percent larger than today's birds. Meat and eggs served as food, bones as tools and feathers as jewelry.

The ancient poet Horace saw him as "pleasant prey", if only he did not have so many tendons. Even today, birds are still offered for sale in some markets in Africa and India . In the Middle Ages , cranes were considered precious prey. The hunting book by Petrus de Crescentii describes the procedure. Accordingly, nets were stretched into which the birds were chased into at dusk. In the falcon book , the Codex De arte venandi cum avibus (About the art of hunting with birds) of the Staufer Emperor Frederick II , the crane is shown in several color miniatures.

The crane as a pest

According to a Byzantine peasant saying, it is easier "to cultivate the rock than fields and hills that have the crane as a neighbor". The ancient Greeks used nets, snares and limes to catch the crane as “seed robbers” and “clod crackers”. In Prussia , Friedrich Wilhelm I had cranes hunted "because of their great damage" to cultivate river valleys and floodplains. Another problem is the endangerment of air traffic by cranes. Their high body weight can cause dangerous damage to aircraft in the event of a collision, such as breaking through the cockpit windows and engine failures. Due to the massive appearance of the cranes in large trains, there is also the risk of multiple hits combined with a dangerous total failure of the engines.

The crane as a timer

A number of peasant rules refer to the migration of the cranes, which is related to sowing and harvest. The Greek writer Hesiod already mentions the following:

"Notice as soon as you have heard the voice of the crane,

who annually sends you the call from the heights out of the clouds.

If he brings the warning to sowing, announces the winter shower ..."

In addition, high-flying cranes should announce good weather.

The crane as an ornamental bird

Cranes were kept as ornamental fowl in China ("first rank bird") and in India ("most distinguished of all feathered birds ") as well as in ancient Egypt . About 4,000 year old reliefs in Egyptian tombs from the time of the pharaohs tell of this . The burial chamber of Ti also indicates that these birds and young cranes were kept in semi-tame herds as sacrificial animals and fattened.

From the writings of the Roman Varro it can be concluded that cranes were later kept as domestic birds. They were used to guard the house and yard, to reliably warn of predators and birds of prey with their loud trumpet-like screams . However, when Charlemagne changed a Salic law, this custom was lost.

literature

General literature

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim : Handbook of the birds of Central Europe. Volume 5: Galliformes and Gruiformes. Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-561-1 .

- B. Hachfeld: The crane. Schlütersche Publishing House, Hanover 1988.

- Peter Matthiessen : The kings of the air. Traveling with cranes. Carl Hanser Verlag, 2007, ISBN 978-3-446-20728-8 .

- Wolfgang Mewes, Günter Nowald, Hartwig Prange: Cranes - Myths. Research. Facts. G. Braun Verlag, Karlsruhe 2003, ISBN 3-7650-8195-7 .

- Günter Nowald, Hermann Dirks: crane encounters - crane worlds. Naturblick Peter Scherbuk Verlag, 2006, ISBN 3-9809695-2-5 .

- Claus-Peter Lieckfeld , Veronika Straaß : The myth of the bird. BLV Buchverlag, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-405-16108-8 .

- Hartwig Prange: The gray crane (Grus grus). (= Die Neue Brehm Bücherei. Volume 229). Westarp Wissenschaften, Hohenwarsleben 2014, ISBN 978-3-89432-346-2 (reprint of the first edition: A. Ziemsen Verlag , Wittenberg Lutherstadt 1989, ISBN 3-7403-0227-5 ).

- Carl-Albrecht von Treuenfels : cranes - birds of happiness. Rasch and Röhring Verlag, Hamburg 2000

- Carl-Albrecht von Treuenfels: Magic of the Cranes. Knesebeck 2005, ISBN 3-89660-266-7 .

- Tobias Böckermann , Willi Rolfes : The crane: A bird on the rise. Atelier in the farmhouse, Fischerhude 2011, ISBN 978-3-88132-177-8 .

- Bernhard Wessling: Crane Thoughts. Margraf Verlag, 2000, ISBN 3-8236-1326-X .

Special literature

- T. Fichtner: Investigations into the behavior and habitat use of summering cranes (Grus grus) in West Mecklenburg. Nürtingen University of Applied Sciences, Department of Land Care, diploma thesis, 1997.

- A. Krull: Investigations into the behavior of wild geese and cranes during the autumn rest on Rügen: Uses of the food areas and reactions to disturbance stimuli. Anhalt University of Applied Sciences - Bernburg Department, diploma thesis, 1995.

- Günter Nowald: Habitat use of a spring resting population of the crane Grus grus. University of Osnabrück, diploma thesis, 1994.

- Günter Nowald: Conditions for reproductive success: On the eco-ethology of the gray crane Grus grus during the rearing of young. University of Osnabrück, dissertation, 2003.

- Wolfgang Mewes: Population development of the crane Grus grus in Germany and its causes. Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, dissertation, 1995.

- Ch. Potthof: Disturbance stimuli and disturbance effects at the breeding site of the gray crane (Grus grus). University of Osnabrück, diploma thesis, 1998.

- Hartwig Prange: Crane Research and Protection in Europe. Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, 1995.

- T. Schulmeyer: For feeding cranes (Grus grus) in the Mecklenburg breeding area. University of Osnabrück, diploma thesis, 1997.

- B. Wilkening: Behavioral and ecological studies on habitat preferences of the crane Grus grus in the state of Brandenburg as well as mathematical-cybernetic habitat models for the evaluation of landscape areas during its reproductive and resting time. Humboldt University Berlin, dissertation, 2003.

Web links

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Grus grus in the Internet Bird Collection

- The working group crane protection Germany and the crane information center Groß Mohrdorf

- Crane Protection European Crane Working Group - ECWG

- Crane Protection Hessen eV

- On the eco-ethology of the gray crane Grus grus while rearing young 9,5 MB (PDF)

- Grus grus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 30 of 2009.

- Feathers of the crane

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be Hartwig Prange: The gray crane (Grus grus). (= Die Neue Brehm Bücherei. Volume 229). Westarp Wissenschaften, Hohenwarsleben 2014, ISBN 978-3-89432-346-2 (reprint of the first edition: A. Ziemsen Verlag, Wittenberg Lutherstadt 1989, ISBN 3-7403-0227-5 ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim: Handbook of the birds of Central Europe. Volume 5: Galliformes and Gruiformes. Aula Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-561-1 .

- ↑ Sound sample / NABU web link

- ↑ Recording Duettruf / B. Wessling Duvenstedter Brook Hamburg ( Memento from August 25, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Sound example with several birds ( Memento from February 20, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) (MP3; 85 kB)

- ↑ a b Bernhard Wessling: Individual Recognition of Cranes, Monitoring and Vocal Communication Analysis by Sonography. Lecture at the 4th European Crane Conference in Verdun, Nov 2000; In: Proceedings 4 ème congrès européen sur les grues, 11-12-13 November 2000, Center Mondial de la Paix Verdun Lorraine. Alain Salvi Ed., Fénétrange (France), 2003, pp. 134-144; see also B. Wessling: Kranichgedanken. Margraf Verlag, 2000, ISBN 3-8236-1326-X .

- ↑ Description of the procedure for frequency analysis ( Memento from September 23, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Grit Pommer: Thousands of cranes are currently resting again at the Kelbra reservoir. thüringer-Allgemeine.de from November 4, 2010 , accessed on October 24, 2011.

- ^ A b T. Schulmeyer: For feeding cranes (Grus grus) in the Mecklenburg breeding area. University of Osnabrück, diploma thesis, 1997.

- ↑ A. Krull: Investigations on the behavior of wild geese and cranes during the autumn rest on Rügen: Uses of the foraging areas and reactions to disturbance stimuli. Anhalt University of Applied Sciences - Bernburg Department, diploma thesis, 1995.

- ↑ JA Alonso, JC Alonso: Color marking of Common Cranes in Europe: first results from the European data base . In: Vogelwelt. 120, 1999, pp. 295-300.

- ↑ B. Wessling: Evaluation of the monitoring of 2 crane species in 5 breeding areas over 10 years. ( Memento from August 26, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Günter Nowald: Habitat use of a spring resting population of the crane Grus grus. University of Osnabrück, diploma thesis, 1994.

- ↑ T. Fichtner: Studies on the behavior and habitat use of summering cranes (Grus grus) in West Mecklenburg. Nürtingen University of Applied Sciences, Department of Land Care, diploma thesis, 1997.

- ↑ B. Wilkening: Behavioral and ecological studies on habitat preferences of the crane Grus grus in the state of Brandenburg as well as mathematical-cybernetic habitat models for the evaluation of landscape areas during its reproductive and resting time. Humboldt University Berlin, dissertation, 2003.

- ↑ Günter Nowald: Conditions for reproductive success: On the eco-ethology of the gray crane Grus grus during the rearing of young. University of Osnabrück, dissertation, 2003.

- ↑ Ch. Potthof: Disturbance stimuli and disturbance effects at the breeding site of the gray crane (Grus grus). University of Osnabrück, diploma thesis, 1998.

- ↑ Norddeutscher Rundfunk, Expedition into the Animal Kingdom, February 14, 2018, 8:15 p.m. - 9:00 p.m.

- ^ Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center: The Cranes. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Evolution and Classification. ( Memento from March 20, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ A b c Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center: The Cranes. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Eurasian Crane (Grus grus). ( Memento of November 13, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The Council of the European Communities 1979: Council Directive of April 2, 1979 on the conservation of wild birds (79/409 / EEC). EG No. L 103: 1 ff. (Bird Protection Directive)

- ^ Birds in Europe: Common Crane

- ↑ Birdlife Factsheet: Common Crane

- ^ Message from Frank Liebig, veterinarian for many years at the eagle and bird of prey station in Wredenhagen.

- ↑ Wolfgang Mewes: Development of the population of the crane Grus grus in Germany and its causes. Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, dissertation, 1995.

- ↑ a b c d Hartwig Prange: Crane Research and Protection in Europe. Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, 1995.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Wolfgang Mewes, Günter Nowald, Hartwig Prange: Kraniche - Mythen. Research. Facts. G. Braun Verlag, Karlsruhe 2003, ISBN 3-7650-8195-7 .

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Claus-Peter Lieckfeld , Veronika Straaß: Mythos Vogel. BLV Buchverlag GmbH & Co. KG, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-405-16108-8 .

- ↑ Peter Engel: Origami. from Angelfish to Zen . Dover Publications, 1994, ISBN 0-486-28138-8 , pp. 24 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ↑ Hekaya: The Wolf and the Crane ( Memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ German poetry library: The Pfab with the crane

- ↑ Hekaya: The Fox and the Crane ( Memento from January 5, 2008 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ textlog.de: Goethe: Fox and crane

- ↑ German poetry library: Walther von der Vogelweide, 03. The crane

- ↑ Wilhelm Busch: The clever crane

- ^ Friedrich Schiller : The Cranes of Ibykus in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ Wissen-im-Netz: Goethe: Faust I. Vor dem Tor ( Memento from January 2, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Zeno.org: The paralyzed crane

- ^ Wikisource.org: The crane

- ↑ DeutscheDichter.de: Brecht: Die Liebenden ( Memento from May 25, 2011 in the Internet Archive )