Turning neck (bird)

| Turning neck | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reversible neck ( Jynx torquilla ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Jynx torquilla | ||||||||||||

| Linnaeus , 1758 |

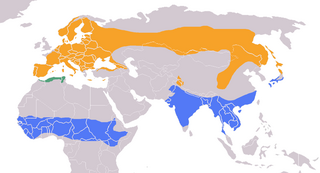

The wryneck ( Jynx torquilla ) is the only European representative of the genus Jynx , which also includes the redthroat wryneck ( Jynx ruficollis ) , which is native to Africa . The species is distributed from northwest Africa eastward in a broad belt to the Asian Pacific coast . Almost all of Europe is populated, but stocks declined sharply in many regions, especially from the second half of the 20th century.

Most of the species' populations are long-distance migrants with wintering areas south of the Sahara , south of the Himalayas and in Southeast Asia . The turning neck is the only largely obligatory migratory bird among the European woodpeckers. Only a few populations in the southernmost distribution areas remain in the breeding area throughout the year. Like all other woodpeckers, it is also a cave-breeder, but is not able to create its own nesting holes, but uses those of other types of woodpecker, especially the great spotted woodpecker , as well as nesting boxes. Reversible necks feed almost exclusively on ants.

Especially in Central Europe the population of the species is continuously declining; however, the entire population is currently not endangered, mainly due to the very large distribution area.

The species , which is only about the size of a lark , got its name because of the noticeable turns of its head. These were named in many national trivial names as well as in the epithet torquilla (lat. Torquere = turn, wind).

Appearance

The nominate form ( J. t. Torquilla ) can be determined very well overall. It is more reminiscent of a small thrush than a woodpecker. The body length is around 17 centimeters, well below that of a song thrush , and the weight is up to 50 grams. The bird has bark-colored, gray-brown plumage with no clear field markings, short, light-gray legs, a gray, also quite short, pointed beak and a noticeably long, gray-brown tail with three indistinct dark-brown cross bars. Beak and legs can have a slightly greenish tinge. In good light, the arrowhead-shaped drawings on the underside and the isabel-colored throat can be seen. The head plumage is raised in excitement situations and thus forms a conspicuous, indistinctly banded hood. A dark brown band runs from the top of the head to the back, which in adult birds is clearly separated from the rest of the gray-brown upper plumage. In young birds it is faded and blends more closely with the color contours of the rest of the upper plumage. A rein tape of the same color runs far behind the eye.

The sexes hardly differ from one another; Females are somewhat duller in color, reddish-brown tones of the abdominal plumage, which are common in males in breeding plumage, are missing in them. The young birds are also very similar to the adult birds, but overall they are more dull brown tones, the throat can be very light, almost white. The arrowhead-shaped drawing of the abdominal plumage is barely recognizable, most likely this area of the body looks slightly banded in dark brown.

voice

Reversible necks can be very noticeable during courtship , breeding and feeding times. Outside of this period, you hardly notice their presence. The singing is very clear and unmistakable and consists of 'gäh' elements increasing in pitch, which quickly sound nasal at first and then loudly 'kje'. Often the partners sing in a duet sitting on a pole, next to them they give off a soft drumming and knocking when the brood is separated. Young birds in particular, but sometimes also adult birds, use a snake-like hissing sound in threatening situations, and snake-like movements are also simulated in such situations. This behavior has been named snake mimicry.

distribution

Breeding area

The breeding area includes parts of North West Africa, the Iberian Peninsula , France , Scotland , the southern North Sea hinterland, Fennoscandia and large parts of the rest of Europe. To the east it stretches in a wide belt to the Pacific Ocean. In the far east there are brood occurrences on Sakhalin , Hokkaido and in North Korea . In northern Lapland , the species reaches its northernmost limit of distribution at around 70 ° north; otherwise it is between 61 ° - 65 ° north. The southern border is inconsistent and includes some island-like occurrences. In Europe, southern Spain, Sicily and northern Greece are sparsely populated, while the Black Sea coast in Turkey is also very sparsely populated . Occasionally the species breeds in the Caucasus . In Asia, the southern limit of distribution runs at about 50 ° north. In China, the southernmost breeding occurrences are in the north of the Sichuan province at around 35 ° north. A clearly isolated island-like breeding area lies in the northwestern Himalayas.

hikes

The wryneck is the only long-distance migrant among the European woodpeckers. Only the island populations (Corsica, Sardinia, Sicily and Cyprus) are partly resident birds or short-distance migrants , as is J. t. mauretanica and the southernmost populations of the Asian subspecies. The nomination form will move out on a broad front from mid-August. The Alps are mostly flown over, while the Mediterranean is flown around by the western migrants via Spain and Gibraltar, by the eastern migrants via the Balkans and the Aegean Island Bridge , or the Bosporus - Sinai route. Wintering is increasing in southern Spain, the southern mainland of Greece and some Greek islands. North Scandinavian populations move partly over Great Britain, where some specimens have successfully wintered. In Central Europe, the homecomers do not appear before the second decade of March, more often until mid-April. Birds that breed in the Northern Palearctic do not reach their breeding area until early May or later.

Reversible necks pull mainly at night and mostly individually.

The wintering area of the European species lies south of the Sahara , in a wide strip from Senegal , Gambia and Sierra Leone in the west to Ethiopia in the east; to the south it extends to the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Cameroon . The West Asian populations also prefer these wintering areas. The Central and East Asian breeding birds overwinter on the Indian subcontinent and in southern East Asia including southern Japan. Occasionally, East Asian homecomers come to West Alaska .

habitat

Reversible necks inhabit open and semi-open climatically favorable landscapes with at least individual trees. Closed forests are avoided as well as treeless steppes, deserts and high mountains. Above all, park landscapes, orchards, large gardens and wine-growing areas, often with broken masonry, are ideal habitats of this type. Light birch, pine and larch forests, and more rarely even alluvial forests, are also populated. The availability of certain ant species and breeding opportunities in woodpecker holes, natural tree hollows or nesting boxes limit the occurrence. Lately, reversible necks have populated windbreak lanes and large-scale clearings created by windbreak, especially in south-western Central Europe. In general, the birds prefer areas with a continental climate; those with a moist maritime climate, such as the French Atlantic coast, cannot be used by the wryneck as a breeding area, or only in very small numbers.

The Wendehals is primarily a type of lowland and hill country level below 1000 meters. Occasionally, breeding occurrences were found in the Caucasus and the Alps at an altitude of over 1,600 meters.

In the wintering regions, diverse habitats rich in insects, especially acacia savannas, are sought out. They range from the lowlands to the montane level. Pure desert areas are only visited temporarily and at their edges, closed rainforests not at all.

Food and subsistence

In the breeding area, the wryneck is very dependent on the occurrence of certain species of ants: lawn , meadow and garden ants are preferred, formica species such as the red wood ant are mostly avoided. Larvae and pupae predominate, but fully developed ants and also sex animals are also part of the diet of the species. Other insects such as aphids , caterpillars or beetles as well as fruits and berries are also consumed to a very small extent . The tendency of the reversible neck to pick up various, mostly shiny objects, enter them into the nesting cavity and possibly feed them to the young is striking and has not been fully clarified. This includes plastic materials, metal parts, aluminum foil, porcelain fragments and others. Such materials have been found in the stomachs of some dead chicks.

Reversible necks occasionally raid the breeding caves of other cave breeders, primarily those of titmice and flycatchers . Clutches found are destroyed and usually dropped outside the brood cavity. It is unclear whether reversible necks sometimes also eat eggs or young birds. The food is almost exclusively picked up on the ground with the help of the long, sticky tongue. Sometimes ant burrows are opened with beak blows. Indigestible food components are deposited in spittle balls (also called vaults). Turnnecks hunt less often on trees or walls. However, unlike other woodpeckers, they are not able to loosen the tree bark with the help of their beak and look for insects underneath.

behavior

The wryneck is diurnal and can often be seen in the entrance to its brood cave. The bird is one of the moderately fast fliers, whereby it flies its wings in the trough of the waves. It hardly climbs and can hardly support itself with the non-stiff tail feathers. Very often it is on the ground, mostly hopping; there it is most likely to be confused. The name-giving jerky head turns are only very noticeable in threatening situations. In this situation, the head feathers are raised and the tail spread apart while the body is usually in an upright position. The head is turned and turned, the tongue can also be thrown forward. The bird is not very shy. During the breeding season it lives in pairs and territorial, otherwise, especially in the wintering area, solitary and roaming. Young birds are acoustically quite noticeable during the tour. Reversible necks, like other woodpeckers, cannot land on vertical trunks. Like songbirds, they sit either transversely to the direction of the branches or lengthways, like the nightjar . During the breeding season, wryneck pairs are strictly territorial and vigorously defend their breeding area. Other birds, especially other woodpeckers, are approached immediately and often attacked directly. What is striking is a particularly aggressive behavior towards other cave breeders , whose broods are often destroyed by reversible necks.

Breeding biology

Courtship

Unlike some other woodpeckers, in which a loose pair cohesion persists even over the winter months, reversible necks lead a breeding season marriage; the ties between the partners cease when the boys fledged. There can be a change of partner even with second broods. Due to the very high loyalty of both sexes to the breeding site, however, re-breeding occurs relatively often. Immediately after arriving in the breeding area, the partners begin the courtship, which mainly consists of long pursuit flights, showing the breeding caves and conspicuous series of calls; the latter are usually presented from low, often exposed singing points, such as isolated bushes or stakes, both at the district boundaries and in the center of the district. Both sexes take part in the nesting site exploration. Copulations usually take place on the ground, only rarely on branches. Towards the end of the courtship, the male reduces his singing activity and confines it to only one singing point near the nest box. After the first egg is deposited, reversible necks are very hidden.

Reproduction and breeding

As a cave breeder, unable to create caves for itself, the reversible neck is dependent on the existence of natural tree hollows or woodpecker hollows. He also accepts nesting boxes. Often already occupied breeding caves are occupied and the previous owners and their eggs or young are removed. The species itself also suffers from such attacks, especially the great spotted woodpecker ( Dendrocopos major ) and blood woodpecker ( Dendrocopos syriacus ) sometimes radically evacuate turning-necked broods. There are also very few nesting sites in walls or caves of sand martins or kingfishers . According to the species of woodpecker, nesting material is not introduced or only to a very limited extent. The cave itself is not worked on, except for reversible necks to rigorously remove nesting material, egg shells and other remains from previous owners. The clutch size is very variable, but is usually between six and ten, in exceptional cases up to 14 smooth, matt white eggs with an average size of around 21 × 16 millimeters. Small clutches with fewer than 5 eggs were also found in the first brooders, or in the case of very poor food availability. If the first clutch is lost, but often also when the first brood is successful, there are also second clutches with usually a lower number of eggs. Second broods tend to be the rule in populations further south, where some pairs also breed a third time - usually nested . Occasionally, clutches with over 20 eggs were found. It is assumed that intraspecific brood parasitism is present in such super-locations, i.e. at least a second female was involved in its development. The eggs are laid every day and initially only warmed by the female, but not firmly incubated. After the last eggs have been deposited, both partners incubate so that the chicks only hatch in short time intervals. The nestling period, during which both parents care for the brood, is around 20 days. Fledging reversible necks are only run by their parents for a short time (two weeks at the most). During this time their begging calls are very noticeable. Then they leave the parents' area, mostly in the direction of the train.

Systematics

The two species of the genus Jynx represent a very different small group within the woodpeckers . They form the subfamily Jynginae. This is the sister taxon to the two other subfamilies of the woodpeckers, the Picumninae and the Picinae. They are probably among the oldest stages of development within the family. Many subspecies have been described, most of which, however, are to be considered as individual coloring variants. As of 2016, four subspecies are still recognized.

- Jynx torquilla torquilla Linnaeus , 1758 : Much of Europe and Asia. Winters in southern Spain, the Balearic Islands , south of the Himalayas and southern East Asia. The previously described subspecies J. t. sarudnyi , J. t. chinensis and J. t. japonica are no longer generally recognized.

- Jynx torquilla tschusii Kleinschmidt , 1907 : Corsica , southern Italy , Sardinia , Sicily and the eastern Adriatic coast . Significantly darker than the nominate form with more contrasting dark markings on the top and bottom. Winters in Africa, partly north of the Sahara. Some populations in Sicily and Calabria are annual birds .

- Jynx torquilla mauretanica Rothschild , 1909 : Maghreb . Similar to J. t. Tschusii, however, somewhat smaller and paler on the underside. Mostly resident .

- Jynx torquilla himalayana Vaurie , 1959 : Northwest Himalayas: Northwest Pakistan to Himachal Pradesh . More clearly banded on the underside than the other subspecies. Winters in lower regions or a little south of the range.

Inventory and inventory trends

In its large range, the entire population of the species is currently not threatened.

In terms of quantity and population dynamics, the total stock can only be recorded in Europe. It is estimated at almost 600,000 breeding pairs. The stock has been declining here since the beginning of the 19th century. The stock reductions took place in longer cycles, which were followed in some areas by recovery and area expansions. Since the beginning of the 1960s, the thinning of the population accelerated enormously, so that the species from Great Britain almost completely disappeared and large areas of northwestern Europe were largely evacuated. In Central Europe, the previously extensive settlement thinned out and reduced to island occurrences in climatically and structurally favored regions. The species is also continually declining in south-west and south-east Europe. The decline seems to have slowed since the beginning of the 21st century, and resettlement has also been noted in some areas.

2000–3000 pairs are currently breeding in Switzerland. A similar population size is assumed in Austria, but detailed regional studies indicate significantly lower population numbers. There are also only a few current inventory surveys from Germany. In 1985 at least 1250 breeding pairs were still breeding in Lower Saxony and Bremen. In 1997, 250 occupied territories were counted and in 2005 180. At present (2016) the number of breeding pairs in Germany should not significantly exceed 10,000. In the Red List of Germany's breeding birds from 2015, the species is listed in Category 2 as critically endangered.

The main causes of this development are changes in the landscape, such as clearing the landscape, destroying the orchards, loss of dry grasslands and the like. a., in changed agricultural culture methods such as bringing forward mowing dates, frequent or even absent mowing and the increased use of biocides . The loss of edge and buffer zones (unfertilized field margins, fallow land, dry grassland, open areas with little vegetation) and the disappearance of unpaved roads seem to have a particularly serious impact. Changes in forest management, in particular the abandonment of clear-cutting and the large-scale conversion of light pine forests into tall beech and Douglas fir stands lead to the loss of suitable habitats. The turningneck's preferred prey are ants. Their population decreases significantly even with low nitrogen inputs; in addition, they withdraw into ever deeper buildings so that they are no longer accessible to him. Furthermore, the increasingly Atlantic climate is unfavorable for the species, but the populations in southern and southeastern Europe, which are hardly affected by this climate development, are also falling drastically.

Name derivation

According to Greek and Roman mythology, Jynx was a servant of Io . By magic she enticed Jupiter ( Zeus ) to love Io. As a punishment, Juno ( Hera ) turned her into a bird and tied her to a wheel. This wheel was used as a magical tool for love spells.

Torquilla is derived from the Latin verb torquere , which means to twist, to turn and describes the extremely noticeable head turns of this type. In other languages, the national generic names also address this behavior, for example in English ( Wryneck - Schiefhals ) or in Dutch ( Draaihals - Drehhals ).

Figuratively

Because the reversible neck changes its point of view easily and frequently, its name was used early on to designate opportunists . This transmission became very widespread during the fall of the Wall in the GDR .

Trivia

- The singer Werner Böhm has taken the stage name "Gottlieb Wendehals".

- The asteroid (8773) Torquilla was named after this species.

See also

literature

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim (Hrsg.): Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Vol. 9. Aula, Wiesbaden 1994, ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 881-916.

- Gerard Gorman: Woodpeckers of Europe. A Study of the European Picidae. Bruce Coleman 2004. pp 47-56. ISBN 1-872842-05-4

- Hans-Günther Bauer, P. Berthold: The breeding birds of Central Europe. Existence and endangerment. Aula, Wiesbaden 1997, pp. 283f. ISBN 3-89104-613-8

- Ludwig Sothmann, carpenter, Ranftl: The whinchat - bird of the year 1987. The turning neck - bird of the year 1988. Bavarian Academy for Nature Conservation and Landscape Management , Laufen / Salzach 1989. ISBN 3-924374-55-4

- Viktor Wember: The names of the birds of Europe. Meaning of the German and scientific names. AULA-Verlag GmbH Wiebelsheim 2005. p. 114. ISBN 3-89104-678-2

- Hans Winkler and David A.Christie: Woodpeckers (Picidae). In: J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, DA Christie and E. de Juana (Eds.): Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (Retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52286 on September 9, 2016).

- Hans Winkler, David A. Christie, David Nurney: Woodpeckers. A Guide to the Woodpeckers, Piculets, and Wrynecks of the World . Robertsbridge, 1995, ISBN 0-395-72043-5

Individual evidence

- ↑ Birdlife data sheet

- ↑ Voice examples at xeno-canto

- ↑ Jochen Hölzinger and Ulrich Mahler: The birds of Baden-Württemberg. Non-songbirds 3. Ulmer-Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 3-8001-3908-1 . P. 373

- ↑ Hans Winkler and David A.Christie (2016). Woodpeckers (Picidae) . In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, DA & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (Retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52286 on September 9, 2016).

- ↑ Hans Winkler and David A.Christie (2016). Woodpeckers (Picidae) . In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, DA & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (Retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52286 on September 9, 2016) - Systematics.

- ↑ Hans Winkler, David A. Christie, David Nurney: Woodpeckers. A Guide to the Woodpeckers, Piculets, and Wrynecks of the World . Robertsbridge, 1995, ISBN 0-395-72043-5 . P. 168

- ↑ Hans Winkler and David A.Christie (2016). Woodpeckers (Picidae) . In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, DA & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (Retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52286 on September 9, 2016).

- ↑ IUCN red list

- ↑ Jan Wübbenhorst: The Wendehals (Jynx torquilla) in Lower Saxony and Bremen: Distribution, breeding population and choice of habitat 2005–2010 as well as causes of danger, protection and conservation status. In: Vogelkdl. Ber. Lower Saxony. 43 (2012). P. 16

- ↑ Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim (ed.): Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Edit and a. by Kurt M. Bauer and Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim. 17 volumes in 23 parts. Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft, Frankfurt am Main 1966ff., Aula-Verlag , Wiesbaden 1985ff. (2nd edition) - Volume 9. Columbiformes - Piciformes . Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1994 (2nd edition, 1st edition 1980). ISBN 3-89104-562-X , pp. 891-894

- ↑ Jochen Hölzinger and Ulrich Mahler: The birds of Baden-Württemberg. Non-songbirds 3. Ulmer-Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 3-8001-3908-1 . P. 377 ff.

- ↑ Hans Winkler and David A. Christie (2016). Woodpeckers (Picidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, DA & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (Retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52286 on September 9, 2016)

- ↑ data sheet Wendehals-Sempach

- ↑ Birdlife data sheet

- ↑ W. Weißmair, H. Kurz: On the stock situation of the turning neck (Jynx torquilla) in Upper Austria from 2002–2012. In: Vogelkdl. Message Upper Austria. Naturschutz aktuell 2012, 20 (1-2). , Pp. 49-64, PDF on ZOBODAT

- ↑ Jann Wübbenhorst: The Wendehals (Jynx torquilla) in Lower Saxony and Bremen: Distribution, breeding population and choice of habitat 2005–2010 as well as endangerment causes, protection and conservation status. In: Vogelkdl. Ber. Lower Saxony. 43 (2012)

- ↑ Jochen Hölzinger and Ulrich Mahler: The birds of Baden-Württemberg. Non-songbirds 3. Ulmer-Stuttgart 2001. ISBN 3-8001-3908-1 . P. 377 ff.

- ↑ Jann Wübbenhorst: The Wendehals (Jynx torquilla) in Lower Saxony and Bremen: Distribution, breeding population and choice of habitat 2005–2010 as well as endangerment causes, protection and conservation status. In: Vogelkdl. Ber. Lower Saxony. 43 (2012)

- ↑ Christoph Grüneberg, Hans-Günther Bauer, Heiko Haupt, Ommo Hüppop, Torsten Ryslavy, Peter Südbeck: Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds , 5 version . In: German Council for Bird Protection (Hrsg.): Reports on bird protection . tape 52 , November 30, 2015.

- ↑ Jann Wübbenhorst: The Wendehals (Jynx torquilla) in Lower Saxony and Bremen: Distribution, breeding population and choice of habitat 2005–2010 as well as endangerment causes, protection and conservation status. In: Vogelkdl. Ber. Lower Saxony. 43 (2012). S.

- ^ Wilhelm Vollmer, Johannes Minckwitz: Dr. Vollmer's dictionary of the mythology of all peoples , 3rd edition, Hoffmann'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart 1874, p. 19, online . Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ Richard Engelmann : Iynx 1) . In: Wilhelm Heinrich Roscher (Hrsg.): Detailed lexicon of Greek and Roman mythology . Volume 2.1, Leipzig 1894, Col. 772 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Etymological dictionary of the German language

- ↑ 8773 Torquilla (5006 T-2). In: NASA . June 11, 2010, accessed July 12, 2017 .

Web links

- Jynx torquilla videos, photos, and sound recordings in the Internet Bird Collection

- Datasheet birdlife international 2005 (PDF file; 330 kB) (English)

- Camouflage coloring of the bird - Revierruf (Dutch)

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 4.6 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (English)

- Jynx torquilla inthe IUCN 2012 Red List of Threatened Species . 2. Listed by: BirdLife International, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- Reversible neck feathers