herring gull

| herring gull | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Herring gull ( Larus argentatus ) |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||||

| Larus argentatus | ||||||||||||

| Pontoppidan , 1763 |

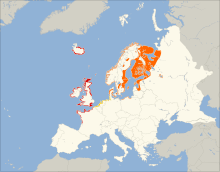

The gull ( Larus argentatus ) is a bird art within the gulls (Larinae) and the most common Großmöwe in Northern and Western Europe. Their distribution area extends from the White Sea over the coasts of Fennoscandia , the Baltic Sea , the North Sea and the English Channel as well as over large parts of the Atlantic coast of France and the British Isles . The species is also found in Iceland .

Herring gulls are colony breeders whose breeding grounds are mostly on inaccessible islands or on cliffs. In many places, however, the species also breeds in dune areas or salt marshes . Like most seagulls, it is omnivorous , but feeds primarily on crustaceans and mollusks , fish and human waste. While the northern populations are migratory birds , most of the remaining herring gulls remain near their breeding grounds. However, young herring gulls in particular migrate long distances and can then also be found far inland. After the species had been severely decimated in the 19th century by collecting the eggs and hunting, the populations recovered in the course of the 20th century.

The herring gull has been the subject of research and has been very well studied as a species. In particular, the behavioral scientist Nikolaas Tinbergen has dealt with it in detail. Until the end of the 20th century, many gull taxa , which are now recognized as separate species, were considered subspecies of the herring gull. The evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr therefore used the herring gull as an example for the theory of the ring species . After a thorough revision of the gull systematics at the beginning of the 21st century, the situation is much more differentiated. In the 1990s, the steppe , Mediterranean and Armenian gulls were temporarily classified as "white-headed gulls" and later as their own Species erected. Around 2005, the subspecies smithsonianus as American herring gull ( Larus smithsonianus ) and the subspecies vegae as Eastern Siberian gull ( Larus vegae ) were granted species status. The herring gull in its current definition is quite close to the Mediterranean gull and the black-headed gull , but only distantly related to the herring and steppe gull. The American herring gull is also not very close to it.

description

At 55–67 cm, the herring gull is about the same size as a common buzzard , the wingspan is even wider at 125–155 cm. The look of this common great gull looks a bit grim, the highest point of the head is behind the eye. The relatively chunky beak is between 44 and 65 mm long. Compared to other species of the genus, the wings are of medium length, they exceed the tail by 3–6 cm when the bird is sitting. The umbrella feathers form a distinct step on the back, the body looks relatively full. A sexual dimorphism is not pronounced with regard to the plumage. Males are larger with a more voluminous beak tip and a flatter forehead, females appear short-billed with a rounded forehead. The breeding dress differs from the plain dress by a dashed head. Young herring gulls can no longer be distinguished from adult birds after the age of four . The legs and feet are reddish in color in all clothes, but there are also individuals with yellow legs, especially in the Baltic States (see geographical variation).

Adult birds

In the splendid plumage of adult birds, the beak is yellow with a red gony spot , which, in contrast to the Mediterranean seagull , is limited to the lower bill . The iris is usually sulfur yellow, sometimes bright yellow or whitish, the eye is surrounded by a yellow, orange-yellow or red ring. The head, neck, nape and underside, as well as rump and tail, are pure white. The mantle, back and shoulder feathers, like the upper side of the wing, are light bluish-gray, but in some birds the bluish tint may be missing. The leading edge of the wing is narrowly white, the rear edge is broadly lined with white. The tip of the hand wing is black with white spots in the area of the wing tips. The outer, tenth hand swing arm - the eleventh is stunted - is largely black with a gray component at the base and a little way up the inner flag. On the farther inward hand wings the proportion of black becomes less and less until it is only visible as a small remainder - in most birds of the German population on the fifth hand wing - and is missing on the other wings. In addition, the tips of the arms are white. There is also another white field on the two outer wings of the hand - separated from the tip by a subterminal black band. On the folded wing, the white tips look like a series of rounded points.

In the winter plumage, the white plumage of the head of adult birds is interspersed with gray-brown dashes. The dotted lines vary from person to person, but often extend to the neck and front chest. On the beak there is some black above or next to the red gony spot.

Subadult birds

Youth dress

The youth dress of the herring gull appears gray-brown overall. The bill is blackish with a slightly lightened base of the mandible, the eye is dark. The head and underside are dotted with dark brown lines and feather centers on a whitish background. The dark dashes condense around the eye, become stronger on the flanks and on the lower tail coverts to form distinctive bands. Coat and shoulder feathers appear strong and regularly scaled due to dark brown feather centers and beige hems. Above all towards the lower back and the upper tail ceilings there are feather centers with oak leaf-like wavy edges, arches or bands, as well as on the quite variable umbrella feathers. The arm covers wear dark bandages on a beige background. The dark brown arm wings have a white lace border and a light gray-brown inner flag. The feathers of the hand wing are black-brown with narrow, whitish hems, except for the light gray-brown lightened inner hand wings. The control feathers show a dark brown color behind a fine, white tip edge in the distal third, which changes into a dark banding on a white background in the middle or basal third, so that the tail shows a dark band that dissolves as a coarse banding towards the white base .

First winter

The first simple dress differs from the youth dress primarily in the shoulder and back feathers. These show beige to warm brown centers over light hems, which are bordered by a narrow, dark subterminal band and have arrow-shaped shaft spots or dark transverse bands in the central feather part. Shoulders and back no longer appear scaled, but more finely banded. The head, neck and chest appear lighter, but still have dark lines - especially around the eye and on the top of the head - as well as dark spots on the chest. Usually the base of the beak lightens up a bit from autumn onwards.

Second winter

Birds in the second winter are similar to those in the first winter, but are usually noticeably lighter on the head, neck and underside. The ligaments on the feathers on the front back and shoulders are wider, and in some birds light gray feathers are mixed into the back plumage - in some individuals they can also predominate. The drawing on the large arm covers appears more diffuse and consists of fine scribbles. The small arm covers no longer show the dark centers of the youth dress, but are banded. Likewise, the shield springs are no longer predominantly dark, but are lightened by light bands. A good distinguishing feature from the first winter dress is the wings, which are more blackish than dark brown and especially on the folded wing show distinctive, light and crescent-shaped end seams. On the control springs, the dark subterminal band no longer runs in stripes into the white spring base, but rather marbled. Another age characteristic is the color of the beak, which has at least one light-colored tip, but in some individuals it has an extensive flesh-colored base. The iris is also clearly lightened in many birds.

Vocalizations

The spectrum of vocal expressions of the herring gull - as with all other species of the genus Larus - is very broad and the meaning of the calls is sometimes very complex. Some are used quite universally and vary in intensity, emphasis, duration or speed depending on the situation, others only occur in connection with certain behaviors.

The main call (audio sample) is a light to piercing, pulled down kiu or kiau . It is particularly variable and occurs in many situations. It expresses excitement of varying intensity up to alarm or is simply intended to arouse the attention of other individuals. A function as a typical contact call cannot be observed. A particularly drawn out and plaintive variant, the so-called "woolly cry", can be heard during the inspection flight before the breeding season. When attacking predators, it sounds short and sharp ( charge call ).

Another alarming utterance is the “staccator call” (audio sample), a deep and cackling ha-ha-ha or gä-gä-gäg . It expresses the willingness to flee or encourages other individuals and especially young birds to flee. The decisive factor here is the rhythm, because young birds also react to a corresponding knock in the experiment.

The cheering of the herring gull (audio sample) can be described as aau aau au kjiiiau kjau kjau . It is usually introduced by a few deep barking sounds, followed by a very excited, high-pitched sound and then a series of calls that descends in intensity and pitch. The introductory barking, which can also be described as hau or bau , can also be heard separately as a request to take off. In flight it is synchronized with the wing movements and is then a two-syllable aa-o .

The "Katzenruf" ( mew call , audio sample) sounds like the drawn out meowing of a house cat. It can be heard above all in breeding colonies and expresses a positive relationship with partner, nest and young.

When creating a nest hollow, a strange guttural sound can be heard. Because of the stereotypical beak movements that take place during this time, it is called the " choking call ". It is a deep huo-huo-huo , in which the tongue bone is lowered, so that the physiognomy of the birds gets a peculiar expression. In addition, the chest is moved rhythmically. The entire behavior can also occur in connection with aggressiveness towards conspecifics.

In connection with the courtship event, the “Schnappruf” ( begging call ) can be heard - a soft, melodic, individually quite variable and two-syllable ai . The female thus initiates courtship feeding; it can be heard from both sexes before copulation. It develops from the begging cry of the young birds. During copulation, the male utters a croaking, increasing and decreasing cackle that resembles the sound of the pestle.

Different sounds can be heard from young birds - such a tender, melodic wüi-a or hüi as a voice -feeling and appeasement sound , a sharp, intense tschä-lä-lä or tschi -li-li as "begging tears" from younger chicks and a nasal tremolating series (audio sample) as voice feel and flight call from older boys.

distribution

Since the North American and East Siberian subspecies were separated as separate species, the distribution of the herring gull has been limited to northern and western Europe. It occurs here on the Faroe Islands , on the coasts of Iceland and the British Isles , as well as on the French Bay of Biscay coast south to the Gironde , on the coasts of Brittany , Normandy and the English Channel , on the coasts of the North and Baltic Seas and of Fennoscandia and there up to the Murman coast . In the south of Fennoscandia, the brood distribution includes large parts of the interior.

hikes

The herring gull is mostly stationary and line bird , only the northern populations are partial migrants . Many populations overwinter near the breeding sites, where they can be found in food-rich places such as fishing ports or landfills. Up to 20,000 birds can gather here. Birds in the first winter tend to disperse more than adult birds and often cover longer distances. But birds pass the furthest in the second winter. From the following spring these birds will start to migrate back home.

The birds of Northern Norway, Northern Russia and Northern Finland regularly migrate long distances, jumping over populations more southerly. Their wintering areas extend from southern Scandinavia to the British Isles. The inland populations of southern Scandinavia almost completely clear their breeding areas in winter and can then be found on the coasts. Some southern Scandinavian and Baltic birds migrate, sometimes short distances, in a south-westerly or westerly direction.

Overall, the main wintering area of the herring gull extends from the southwestern Baltic Sea region and southern Norway to the British Isles in the west and the Loire in France, or on the Biscay coast to the Gironde. In the Netherlands, northern Germany, northern Poland and the Baltic states, the species is also found relatively far inland. In Western Europe it is still found scattered as far as the Iberian Peninsula and small numbers can be found regularly in Northern Italy. Odd guests have been found as far as the eastern Mediterranean and even Newfoundland .

Adult herring gulls leave their breeding colonies immediately after the young have fledged, this year apparently staying a little longer. In late summer and autumn, large numbers gather in the German-Dutch Wadden Sea (concentrations of up to 50,000 birds) and in northwest Jutland (up to 20,000). In the interior, the species appears dispersed from August and in larger numbers from the end of October. Migratory birds from Scandinavia mainly migrate between September and November; in Germany, a train peak can be felt in October / November. The train is largely completed by the end of November, only dispersions will then take place. In December and January, in a few years' time, many overwinterers leave continental Europe because of freezing waters and pass to western Central Europe and the British Isles, where peak numbers (up to around 380,000) are reached between mid-December and mid-February. Breeding birds return to the breeding grounds from January; Non-breeders sometimes stay inland even in March. In small numbers, predominantly sub-adult birds can be found in inland waterways between May and August.

Geographic variation

Two subspecies are recognized, of which the western subspecies L. a. In the adult dress, argenteus differs from the nominate form by a combination of a relatively light upper side and more extensive black on the wing tip. In the Baltic States and western Russia there was a population of herring gulls until the 1950s in which all adult birds had yellow legs. This was at times listed as a subspecies omissus and later added to the "white-headed gull" ( L. cachinnans ). From the 1960s, however, these populations mixed with more western birds, so that this form has almost disappeared today and only a few yellow-legged individuals appear.

- L. a. argenteus C. L. Brehm , 1822 - Iceland, Faroe Islands, British Isles and West France to West Germany

- L. a. argentatus Pontoppidan , 1763 - Denmark and Fennoscandia to the Murman coast

habitat

The herring gull breeds mainly on coasts and prefers breeding sites here that are safe from floods and soil enemies. These are generally rocky cliffs with offshore islands and skerries . Where such structures are missing - such as on the German North Sea coast - it also breeds in sand dunes and in the foreland of dikes , on rinsing areas and gravel banks, as well as in island grassland and salt marshes . In the Netherlands broods have been found in cabbage fields and the species sometimes nests on buildings.

Only in Sweden, Finland and northwestern Russia as well as in parts of the Baltic states does the herring gull breed in inland in large numbers. It occurs here in moor and tundra landscapes , but also on mountain lakes up to an altitude of 2000 m.

The herring gull also primarily looks for food in the coastal area. It is often found here on beaches and in the Wadden Sea and rarely more than 20 km from the coast on the open sea. Of particular importance, however, are all year round places where waste provides a safe source of food, such as landfills, fishing ports and operations, but also slaughterhouses. However, the species is also found in smaller numbers on agricultural and floodplain areas, on sewage ponds and sewage fields as well as on inland waterways, including in urban areas .

nutrition

Due to their opportunistic feeding behavior, the herring gull shows a very broad spectrum of food and prey. Often a locally or seasonally rich source of food is used extensively and one-sidedly. But when there is none, the species is quite inventive in finding replacements. In the course of the seasons, regionally or with individual birds, the focus can be set differently.

Animal food makes up a large proportion, but fish plays a smaller role than is often reported. This is more true of the Mediterranean seagull. Since the herring gull primarily searches for its food in the intertidal zone, crustaceans and mollusks - in particular sea crabs and North Sea shrimp as well as the common cockle , mussels and the Baltic flat mussel - make up the majority. In the summer half of the year the proportion of crustaceans increases to up to 90%, in winter mussels are mostly dominant. In smaller proportions, there are other species of crustaceans and molluscs , fish , echinoderms , insects , bird eggs or young birds or even small mammals up to the size of young rabbits . Small birds are sometimes captured on the sea migration when they are exhausted and easy to catch. Larger animals are only taken in as carrion.

Vegetable food is only of minor importance. It is mostly unconsciously eaten in the form of algae or small parts of plants together with other food. Occasionally, however, berries or cereals are also consumed.

Human waste can make up a significant proportion of food, especially in winter. These are mainly searched for in landfills, fishing ports and slaughterhouses, but the seagulls also follow fishing boats and excursion steamers, use the dumped rubbish from larger ships or search waste bins. They also take on indigestible items such as plastic parts, silver foil, cigarette filters or the like.

Reproduction

Herring gulls only reach sexual maturity between the ages of 3 and 7. Some birds breed from the third year, but mostly only with little competition for nesting sites and outside of colonies. The majority only brood from the fifth year on.

There is an annual brood. In the event of loss, there may be up to two times, in rare cases a third time.

Herring gulls have a monogamous seasonal marriage and re-mating in subsequent years is very common due to the high degree of loyalty to breeding sites and partners. Many partners therefore have a monogamous permanent marriage. Sometimes there are irregularities such as intermittent, sometimes even multi-year mating with other partners while the old couple relationship continues or courtship activities with other partners. In some cases, real triangular relationships were documented over several years.

Colonies and territorial behavior

Herring gulls breed individually or in colonies, the size of which can be between under 10 and over 15,000 breeding pairs. The nest distance is usually around 1.85 m, but can also be only about 60 cm if there are visible barriers between the nests. The territory of a couple extends over the vicinity of an original "stand" of the male, in the vicinity of which the nest will later be built. The boundaries are relatively diffuse and the size of the territory depends on the dominance and willingness of the male to defend himself.

The colonies are reoccupied by solitary birds from October, but mostly not until February. Initially, the colony is often only populated at high tide, while at low tide all birds are in the mudflats foraging for food. A permanent occupation can only be recorded from mid-March.

Pair formation and courtship

It is not uncommon for long-term pairs to form pairs in winter, so that many arrive at the breeding grounds already paired. In the case of first breeders, the choice of partner takes place in the “club” and is the responsibility of the female, who chooses a male with a territory. The approach is very slow. Initially, the male reacts with threats or expulsion, while the female tries to identify herself as a female with a humble "humpback position". If this - often only after a few days - is successful, the reaction of the male changes, which the arriving female receives with a series of calls (" shouting "). From now on, courtship feedings and copulations take place regularly . This process is initiated by the female nodding her head, throwing her head almost vertically into the neck and then lowering it again. It goes around the male and begins to plead and snap at the male's throat. The snap call - a faint sound - can be heard. The male reacts with impressive behavior by attacking surrounding rivals, by feeding the female or with nest locks, in which it leads the female to a potential nest location. Both partners then lapse into ritualized nest-building acts while chuckling noises. The copula is often triggered by begging behavior of the male and initiated by rocking the head on both sides.

Begging and courtship feeding can often already be observed in winter, copulations only around 30 days before the eggs are laid. The peak of courtship behavior is reached around 10 days before the start of laying. After oviposition, it ends relatively suddenly.

Nest building, incubation and rearing of young

The nest is built in locations that are safe from flooding and often in the protection of the vegetation. It is not uncommon for it to be near a conspicuous marking such as bushes, rocks, stakes, boards or boxes. Sometimes it is also "covered" in a stand oat bulbs.

Before the nest is built, play nests are set up in the form of simple hollows, and the final nest is often developed from this. It consists of a sometimes voluminous accumulation of parts of plants such as grass or seaweed. If there is no nesting material, it remains in a dug out hollow that is lined with moulting feathers.

Egg-laying begins in mid-April, a little later in Northern Scandinavia and on the East and West Frisian Islands. The main laying time is in May, and hardly any eggs are laid from mid-July. Up until the beginning of August there will be additional clutch.

The clutch consists of 2–3 smooth and dull eggs, which are usually darkly spotted, dotted or scrawled on a beige, light brown or olive green background. Color and pattern are very variable, sometimes bluish-white, cream-colored or pink-tinted eggs appear. The dimensions are 70 x 50 mm.

The eggs are laid 2-3 days apart and incubated from the first egg on, with the partners alternating. The incubation period is between 25 and 33 days.

Young herring gulls are place stools that are still fudged a lot in the first few days . They fledge after 35–59 days. The young birds stay near their parents for another 19–47 days and are still fed - in rare cases even until the next brood.

Mortality and Age

As ring finds and readings of ringed animals show, herring gulls can live to be over 20, in some cases even over 30 years old. A gull ringed in the Netherlands reached an age of 34 years and nine months, a gull ringed in Germany was 30 years old.

Systematics

The internal systematics of the genus Larus is extremely complex, and in particular the research of the taxonomic relationships within the argentatus-fuscus (black and black-backed gull) has been a special scientific challenge in the last few decades, some of which still exists. Many questions have not yet been conclusively clarified, and current proposals for nomenclature and taxonomy are also controversial.

1925 Affiliate Jonathan Dwight , the mid-size, spread to the northern hemisphere large gulls Gull ( L. argentatus ) California Gull ( L. californicus ), Weißkopfmöwe ( L. cachinnans ), Gull ( L. fuscus ), Western Gull ( L. occidentalis ), slaty-backed gull ( L. schistisagus ), bering gull ( L. glaucescens ), ice gull ( L. hyperboreus ) and polar gull ( L. glaucoides ). This division did not go unchallenged; In 1934 Boris Stegmann combined all of the above-mentioned species in the herring gull ( L. argentatus ) taxon , other authors grouped the herring gull with other taxa (e.g. white-headed, arctic and polar gulls), and some questioned the affiliation of various subspecies.

Research into mitochondrial DNA at the beginning of the 21st century found that some of the taxa Dwight defined were paraphyletic . Today there is much to be said for a division of the herring gull into an American, a European and an East Siberian taxon.

Reasons for a species status of the American form are DNA findings, biogeographical isolation and differences in the first winter dress and in the vocal expressions. The latter deviate so much that European herring gulls do not respond to sound mockups with the calls of American birds.

The status of the East Siberian form vegae is still unclear . Some authors regard this as a separate species ( L. vegae ), but according to findings from 2008 it is to be regarded as a subspecies of the American herring gull. In addition, the form mongolicus , which was previously associated with the steppe gull ( L. cachinnans ), should also be included in this taxon.

Inventory development

The herring gull population comprises around 700,000–850,000 breeding pairs; Great Britain and Norway hold the largest stocks, followed by France, Sweden, the Netherlands, Denmark and Germany.

In the course of the 20th century, the population in these countries increased dramatically. First, the populations recovered after the First World War , after commercial egg collection was banned and the species was placed under protection in numerous sea bird sanctuaries. As a result, for example, Iceland was first settled in the late 1920s. A second surge in populations was felt in the 1950s. The reason for this was the increasing adaptation to the human settlement area, where numerous sources of food such as garbage dumps or fish factories ensured a year-round supply and lower winter mortality. In addition to an increase in the population, a further spread to the north and an increased penetration of wintering into the interior were observed.

In total, the stocks in Denmark increased twenty-fold and in Germany fifteen-fold. In the Netherlands, stocks quintupled; in the UK there was annual growth of 13-14%. In some cases massive decimation efforts were countered, such as the systematic destruction of clutches, poisoning or the shooting down of entire colonies. The aim was mostly to protect the populations of other seabird species such as terns and waders. The control measures remained largely unsuccessful or had the opposite effect, as the gaps that had emerged were quickly filled again by immigration or the further spread was promoted by rapid resettlement. Only in Great Britain did the control measures in connection with botulism , salmonella poisoning and better waste recovery lead to a 50% decrease between 1969 and 1987. According to recent studies and perspectives, the population-ecological effects of predatory behavior of species such as the herring or common gull are low. The main reasons for the decline in other seabird species are biotope destruction, the effects of pesticides and disturbances at the breeding site. Effective ways of regulating the population of great gulls are also likely to lie in limiting the abundant food supply at landfills due to improved waste management rather than in control.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Glutz von Blotzheim, p. 530f, N. Tinbergen (1953), p. 9f and F. Goethe (1956), p. 28f.

- ↑ Stuart Fisher: XC29878 Herring Gull Larus argentatus argenteus . xeno-canto.org. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ a b Tinbergen (1953), p. 10, see literature

- ↑ Patrik Åberg: XC64710 Herring Gull Larus argentatus . xeno-canto.org. July 20, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Tinbergen (1953), p. 10f, see literature

- ↑ a b Glutz von Blotzheim, p. 531, see literature

- ↑ Stuart Fisher: XC40008 Herring Gull Larus argentatus argenteus . xeno-canto.org. October 23, 2009. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ F. Goethe (1953), p. 31, see literature

- ↑ Herman van der Meer: XC89886 Herring Gull Larus argentatus . xeno-canto.org. May 5, 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ Tinbergen (1953), p. 11, see literature

- ↑ Stuart Fisher: XC25583 Herring Gull Larus argentatus argenteus . xeno-canto.org. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ↑ F. Goethe (1953), p. 30, see literature

- ↑ a b c Olsen / Larsson, p. 265, s. literature

- ↑ Glutz v. Blotzheim, p. 549, p. literature

- ↑ z. B. Glutz v. Blotzheim, s. literature

- ↑ Olsen / Larsson, p. 262f, s. literature

- ↑ a b c Glutz v. Blotzheim, pp. 550f, s. literature

- ↑ a b c d e Oscar J. Merne: Herring Gull. In: Ward JM Hagemeijer, Michael J. Blair: The EBCC Atlas of European Breeding Birds - their distribution and abundance. T & AD Poyser, London 1997, ISBN 0-85661-091-7 , pp. 338-339.

- ↑ a b F. Goethe, p. 38, s. literature

- ↑ a b M. Temme in Glutz v. Blotzheim, p. 580, p. literature

- ↑ R. Drost in Goethe, p. 46f, see literature

- ↑ Glutz v. Blotzheim, p. 551, p. literature

- ↑ Goethe, p. 48, s. literature

- ↑ Glutz v. Blotzheim, pp. 552f, s. literature

- ↑ Goethe, p. 43f, s. literature

- ↑ Glutz v. Blotzheim, p. 566f, as well as Goethe, p. 28 and p. 49, s. literature

- ↑ K. Hüppop, O. Hüppop: Atlas for bird ringing on Helgoland. In: Vogelwarte. 47 (2009), p. 214.

- ↑ R. Staav, T. Fransson: EURING list of longevity records of European birds. www.euring.org, quoted from K. Hüppop, O. Hüppop: Atlas for bird ringing on Helgoland. In: Vogelwarte. 47 (2009), p. 214.

- ↑ J. Dwight: The gulls of the world; their plumages, moults, variations, relationships and distribution. In: Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 52, 1925, pp. 63–408 and tables V – XV., Referenced in Glutz v. Blotzheim, s. literature

- ↑ BK Stegmann: About the shapes of the large seagulls and their mutual relationships. In: Journal of Ornithology. 82, 1934, pp. 340-380, referenced in Glutz v. Blotzheim, s. literature

- ↑ u. a. G. Sangster, JM Collinson, AG Knox, DT Parkin, L. Svensson: Taxonomic recommendations for British birds: Fourth report. In: Ibis. 149, 2007, pp. 853-857.

- ↑ Olsen / Hansson, p. 239, s. literature

- ↑ JM Collinson, DT Parkin, AG Knox, G. Sangster, L. Svensson: Species boundaries in the Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gull complex. In: British Birds. 101 (7), 2008, pp. 340-363.

- ↑ a b c d Olsen / Larsson (2003), p. 264f, see literature

- ↑ a b c Glutz von Blotzheim, p. 540f, see literature

literature

- Klaus Malling Olsen, Hans Larsson: Gulls of Europe, Asia and North America. (= Helmet identification guides). Christopher Helm, London 2003 (corrected new edition from 2004), ISBN 0-7136-7087-8 .

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim , KM Bauer : Handbook of the birds of Central Europe . Volume 8 / I: Charadriiformes. 3rd part: snipe, gull and alken birds. Aula-Verlag, ISBN 3-923527-00-4 .

- Friedrich Goethe: The herring gull. (= Neue Brehm Bücherei. Issue 182). A. Ziemsen Verlag, Wittenberg Lutherstadt 1956.

- Niko Tinbergen : A Herring Gull's World - The Study of the Social Behavior of Birds. Collins, London 1953. (5th edition. 1976, ISBN 0-00-219444-9 )

- Pierre-Andre Crochet, Jean-Dominique Lebreton, Francois Bonhomme: Systematics of large white-headed gulls: Patterns of mitochondrial DNA variation in western European taxa. In: The Auk . 119 (3), 2002, pp. 603-620.

- M. Gottschling: How do you determine the age of a great gull? In: The falcon. 51. 2004, pp. 124-127. (Full text as pdf; 256 KB)

Web links

- Larus argentatus in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 31 of 2009.

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Larus argentatus in the Internet Bird Collection

- Herring gull feathers