Adolf Hitler

Signature, 1944, presumably produced with a signature machine (see section Further course of the war )

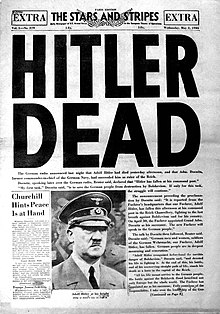

Signature, 1944, presumably produced with a signature machine (see section Further course of the war )Adolf Hitler (born April 20, 1889 in Braunau am Inn , Austria-Hungary , † April 30, 1945 in Berlin ) was a National Socialist German politician of Austrian origin who was dictator of the German Reich from 1933 to 1945 .

From July 1921 chairman of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), he tried to overthrow the Weimar Republic with a coup in Munich in November 1923 . With his writing Mein Kampf (1925/26) he shaped the anti-Semitic and racist ideology of National Socialism.

Hitler was appointed German Chancellor by President Paul von Hindenburg on January 30, 1933 . Within a few months, his regime eliminated the separation of powers , pluralistic democracy , federalism and the rule of law with terror, emergency ordinances , the Enabling Act , conformity laws , organization and party bans . Political opponents were imprisoned, tortured and murdered in concentration camps. In 1934, on the occasion of the " Röhm Putsch " , Hitler had potential rivals murdered in his own ranks. Hindenburg's death on August 2, 1934, he took to the Office of the President with the Chancellor to be united , and ruled ever since as the "Fuehrer and Reich Chancellor."

The German Jews were increasingly marginalized and disenfranchised from 1933, especially by the Nuremberg Laws of September 15, 1935, the November Pogroms 1938 and the Aryanization of companies of Jewish owners as well as numerous other laws and ordinances that gradually allow them to participate in the economic, cultural and social Making life impossible and robbing them of their wealth and livelihoods. He fought the consequences of the global economic crisis and mass unemployment with state investment programs and job creation measures such as the construction of the autobahn and the armament of the Wehrmacht, as well as the establishment of the paramilitary Reich Labor Service . With the armament of the Wehrmacht and the occupation of the Rhineland , Hitler broke the Versailles Treaty in 1936 . The Nazi propaganda presented the economic, social and foreign policy to be successful and so is increased to 1939 Hitler's popularity.

In 1938 he took over direct command of the Wehrmacht and pushed through the "Anschluss" of Austria . With the " smashing of the rest of the Czech Republic " on March 15, 1939, he defied the Munich Agreement of September 30, 1938, which allowed him to annex the Sudetenland to the German Reich . With the conclusion of the so-called Hitler-Stalin Pact of 23./24. The attack on Poland prepared with the Soviet Union on September 1, 1939, which, according to the treaty, had the aim of smashing the Polish state and dividing its territory among the contracting parties and which was soon followed by the Soviet occupation of eastern Poland , solved the Second World War in Europe the end. After the victory over France in the western campaign from May 10 to June 25, 1940 and the beginning of the later failed Battle of Britain on July 10, 1940, he informed representatives of the High Command of the Wehrmacht on July 31, 1940 of his decision to attack the Soviet Union and to wage a war of annihilation against them to conquer " Lebensraum in the east ". He had the war against the Soviet Union , which began on June 22, 1941, prepared and carried out under the code name " Operation Barbarossa ".

During the Second World War, the National Socialists and their accomplices committed numerous mass crimes and genocides . As early as the summer of 1939, Hitler gave instructions to prepare for "adult euthanasia". Between September 1939 and August 1941, more than 70,000 mentally ill and mentally and physically handicapped people were systematically murdered in “ Aktion T4 ”; by the end of the war, more than 200,000 people were systematically murdered through “ euthanasia ”. Hitler's anti-Semitism and racism eventually culminated in the Holocaust . Around 5.6 to 6.3 million Jews were murdered in the Holocaust and up to 500,000 Sinti and Roma in the Porajmos . Hitler authorized the most important steps in the murder of the Jews and was informed about the progress. His criminal policy led to millions of war dead and the destruction of large parts of Germany and Europe.

Early years (1889-1918)

family

Hitler's family came from the Lower Austrian Waldviertel on the border with Bohemia . His parents were the customs officer Alois Hitler (1837-1903) and his third wife Klara Pölzl (1860-1907). Alois was born out of wedlock and until he was 39 years old bore the family name of his mother Maria Anna Schicklgruber (1796–1847). In 1843 she married Johann Georg Hiedler (1792–1857), who did not admit to being a father to Alois for his entire life. It was not until 1876 that his younger brother Johann Nepomuk Hiedler (1807–1888) had him certified as Alois' father and the form of his name changed to Hitler . Some historians consider Johann Nepomuk himself Alois Hitler's father. Klara Pölzl was his granddaughter. Thus Alois was married to his half niece first or second degree.

Adolf Hitler was in on April 22, 1889 Braunau parish church baptized . His older siblings Gustav (1885–1887) and Ida (1886–1888) had died before he was born. The three younger siblings were Otto (* / † 1892, only six days old), Edmund (1894-1900) and Paula (1896-1960). Otto's correct life data were only determined in 2016. Hitler's two older half-siblings Alois junior and Angela Hammitzsch came from his father's second marriage. After the death of their mother, they grew up in the household of Hitler's parents.

Since 1923, Hitler withheld some details of his origins. In 1930 he forbade Alois Hitler junior and his son William Patrick Hitler from introducing themselves to the media as his relatives because his opponents were not allowed to know his origin. He wanted to end public interest in his parentage. Concerned about statements made by his nephew, Hitler is said to have commissioned his lawyer Hans Frank , later governor-general in occupied Poland , to refute his father's Jewish origins in 1930 . After the war, Frank put forward the so-called " Frankenberger thesis ", according to which Hitler's paternal grandfather could have been a Jew. However, this thesis was rejected by all relevant Hitler biographers and refuted in 1971 by Werner Maser . When foreign media repeatedly claimed in 1932/33 that the leader of the anti-Semitic NSDAP had Jewish ancestors from the Polná ghetto , he had two genealogists examine his family tree, which was published in 1937.

After the “Anschluss” of Austria in 1938, Hitler declared the home villages of his father and grandmother, Döllersheim and Strones, a restricted military area. By 1942 he had a large military training area built there, which resettled around 7,000 residents and removed several memorial plaques for his ancestors. His grandmother's grave of honor was also destroyed, while her family's baptismal records were preserved. According to the journalist Wolfgang Zdral , Hitler wanted to use all these measures to suppress doubts about his " Aryan proof " and to prevent incest allegations because of his parents' blood relationship.

schooldays

The family moved to the German border town of Passau in the summer of 1892 because their father was promoted to the head of the customs office . In the spring of 1895 the family returned to Austria and moved into the Rauschergut in Hafeld, so that Hitler attended the one-class elementary school in Fischlham from May onwards . With the move to Lambach in July 1897, he completed the second and third class and finally the fourth class with the move to Leonding . He was considered a good, bright student. From 1900 he attended the K. k. State Realschule Linz , where he showed himself unwilling to learn and twice could not advance to the next class because of missing the performance target. He despised religious instruction from Franz Sales Schwarz , only geography and history lessons from Leopold Pötsch interested him. In Mein Kampf (1925) he emphasized the positive influence of Pötsch. In his high school days, Hitler liked to read books by Karl May , whom he admired all his life. His father had chosen him for a civil service career and punished his unwillingness to learn with frequent, unsuccessful beatings. He died in early 1903. In 1904 his mother sent Hitler to the secondary school in Steyr . There he was not promoted to the ninth grade because of poor school grades. With a temporary ailment, he was able to leave secondary school without a qualification and return to his mother in Linz.

In Linz, Hitler got to know the thinking of the radical anti-Semite and founder of the Pan-German Association , Georg von Schönerer , through classmates, teachers and newspapers . He attended performances of Richard Wagner's operas for the first time , including Rienzi . He later said: "It started at that hour." Under the impression of the main character, according to his friend at the time , August Kubizek, he is said to have said: "I want to be a tribune ."

In Mein Kampf , Hitler presented his school behavior as a study strike against his father and claimed that a serious lung disease had thwarted his school leaving certificate. The father's violence is considered a possible root for his further development. According to Joachim Fest , even during his school days he fluctuated between intensive occupation with various projects and inactivity and showed an inability to work regularly.

Painter in Vienna and Munich

After his father's death, Hitler moved into a half- orphan from 1903 a pro- orphan's pension ; from 1905 he received financial support from his mother and his aunt Johanna. In early 1907 his mother was diagnosed with breast cancer . The Jewish family doctor Eduard Bloch treated them. Since her condition deteriorated rapidly, Hitler is said to have insisted on the use of painful iodoform compresses, which ultimately hastened her death.

From 1906 Hitler wanted to become a painter and later carried this job title. Throughout his life he saw himself as a misunderstood artist . In October 1907 he applied unsuccessfully to study art at the general painting school of the Vienna Art Academy . He initially stayed in Vienna, but returned to Linz when he learned on October 24th that his mother only had a few weeks to live. According to Bloch and Hitler's sister, he looked after the parents' household until the mother's death on December 21, 1907 and looked after her burial two days later. He thanked Bloch, gave him some of his pictures and protected him from arrest by the Gestapo in 1938 .

By pretending to be an art student, Hitler received an orphan's pension of 25 kroner a month from January 1908 to 1913 and his mother's inheritance of no more than 1,000 kroner. From that he was able to live in Vienna for about a year. His guardian Josef Mayrhofer urged him several times in vain to forego his pension portion in favor of his underage sister Paula and to start an apprenticeship. Hitler refused and broke off contact. He despised a “bread and butter” and wanted to become an artist in Vienna. In February 1908 he ignored an invitation from the renowned set designer Alfred Roller , who had offered him an apprenticeship. When he ran out of money, he got a loan of 924 kroner from his aunt Johanna in August. In the second entrance exam at the art academy in September, he was no longer admitted to trial drawing. He withheld this failure and his place of residence from his relatives in order to continue receiving his orphan's pension. That is why he posed as an “academic painter” or “writer” when moving house. He was threatened with conscription for military service in the Austrian army .

After August Kubizek, who shared a room with him in 1908, Hitler was more interested in Wagner operas than in politics. After moving out in November 1908, he rented rooms further and further away from the city center at short intervals, apparently because his lack of money grew. In the autumn of 1909 he moved into a room at 56 Sechshauser Strasse in Vienna for three weeks; after that he was not officially registered for three months. From his testimony in a criminal complaint it can be seen that he lived in a homeless shelter in Meidling . At the beginning of 1910, Hitler moved into the Meldemannstrasse men's dormitory , also a homeless shelter. In 1938 he had all files on his whereabouts in Vienna confiscated and passed off a house in an upscale residential area as his student apartment.

From 1910, Hitler earned money by drawing or copying motifs from Viennese postcards as watercolors . His roommate Reinhold Hanisch sold these for him until July 1910, then the Jewish roommate Siegfried Löffner. He reported Hanisch to the Vienna police in August 1910 for allegedly embezzling a picture of Hitler. The painter Karl Leidenroth reported Hitler anonymously, probably on behalf of Hanisch, for the unauthorized use of the title of "academic painter" and obtained that the police forbade him to use this title. Thereupon Hitler had his pictures sold by the resident of the men's home, Josef Neumann, as well as the dealers Jakob Altenberg and Samuel Morgenstern . All three were of Jewish origin. The roommate in the men's dormitory, Karl Honisch, later wrote that Hitler was “thin, poorly nourished, hollow-cheeked with dark hair that hit him in the face”, and was “shabbily dressed”, sat in the same corner of the office and took pictures every day drawn or painted.

In Vienna, Hitler read newspapers and writings by Pan-Germans , German nationalists, and anti-Semites, including possibly the book Der Unbesiegbare by Guido von List . The latter describes the desired image of the " fate of certain" infallible Germanic heroic prince, the Germans saved from destruction and world domination will lead. This picture , according to the historian Brigitte Hamann , could also explain Hitler's later claimed chosenness and infallibility, which did not allow him to admit any errors. Perhaps he read the magazine Ostara , published by List's student Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels , and the biography of Georg von Schönerer (1912) written by Eduard Pichl . Since 1882 he had demanded the “de-Jewification” and “racial segregation” by law, introduced an Aryan paragraph for his party, represented a ethnic-racist Germanism against the multiculturalism of the Habsburg monarchy and as a substitute religion for Catholic Christianity (“ Los von Rom! ”) . Hitler heard speeches from his supporter, the workers' leader Franz Stein , and his competitor, the Reichsrat member Karl Hermann Wolf . Both fought against the "Jewified" social democracy , Czech nationalists and Slavs . Stein strove for a German national community to overcome the class struggle ; Wolf aspired to a Greater Austria and in 1903 founded the German Workers' Party (Austria-Hungary) with others . Hitler also heard and admired the popular Viennese mayor Karl Lueger , who founded the Christian Social Party (Austria) , advocated Vienna's “ Germanization ” and, as an anti-Semitic and anti-social democratic “tribune”, gave speeches with mass impact. In 1910, according to statements from his roommates in the men's dormitory, Hitler discussed the political consequences of Lueger's death, refused to join the party and advocated a new, nationalist collection movement.

To what extent these influences shaped him is uncertain. At that time, according to Hans Mommsen , his hatred of the Social Democrats, the Habsburg Monarchy and the Czechs was predominant. While some benevolent statements by Hitler about Jews have been passed down up to the summer of 1919, from autumn 1919 onwards he resorted to anti-Semitic clichés that he had come to know in Vienna; since 1923 he presented Schönerer, Wolf and Lueger as his role models.

In May 1913, Hitler received his father's inheritance (around 820 crowns), moved to Munich and rented a room initially shared with Rudolf Häusler at Schleißheimer Strasse 34 ( Maxvorstadt ) . One reason for this was the flight from compulsory military service in Austria. After the annexation of Austria in 1938, he tried to cover up this by confiscating his military service papers. In Munich, among others, Hitler read Houston Stewart Chamberlain's popular fundamentals of the nineteenth century , continued to paint pictures, mostly based on photographs of well-known buildings, and sold them to a Munich art dealer. He later claimed that he longed for a “German city” and wanted to be trained as an “architecture painter”. After the Munich criminal police had taken him on 18 January 1914 and presented at the Austrian Consulate, he was on February 5, 1914 in Salzburg patterned judged to be incapable of weapons and returned from military service.

Hitler's love affairs between 1903 and 1914 are unknown. According to Kubizek and Hanisch, in Vienna he expressed himself contemptuously about female sexuality and fled from advances by women. In 1906 he adored the Linz student Stefanie Isak (later married Rabatsch) without making any contact. Later he referred to an Emilie, perhaps Häusler's sister, as his "first lover". Brigitte Hamann also rates this relationship as wishful thinking. Like the Pan-Germans , Hitler is said to have demanded a ban on prostitution and sexual abstinence for young adults as early as 1908 and practiced the latter himself out of fear of infection with syphilis .

Soldier in the First World War

Like many others, Adolf Hitler enthusiastically welcomed the beginning of the First World War in August 1914 . According to his own account, he successfully asked the Bavarian king with an immediate application dated August 3, 1914 for permission to be integrated into the Bavarian Army as an Austrian . He entered there as a war volunteer on August 16, and on October 8 he was sworn in to the King of Bavaria . Today it is assumed that Hitler's citizenship did not play a role for the Bavarian kingdom when the war broke out, especially since he was not the only Austrian in the regiment. An Austrian special permit, which he later claimed and applied for at short notice, is a legend. On September 1, 1914, he was assigned to the first company of Reserve Infantry Regiment 16 .

Hitler took part in the First Battle of Flanders at the end of October 1914 . On November 1, 1914 he became a corporal transported and on 2 December 1914, the Iron Cross awarded II. Class because he on 15 November 1914 a second messengers during the First Battle of Ypres northwest of Messines the life of the fire under French standing regimental commander had protected and possibly saved. From November 9, 1914 until the end of the war, Hitler served as an orderly and reporter between the regimental staff and the battalion staff at a distance of 1.5 to 5 kilometers from the main battle line , initially at the Wytschaete-Bogen on the western front . Contrary to his later portrayal, he was not a particularly endangered frontline reporter of a battalion or a company and had far better chances of survival than these.

From March 1915 to September 1916 he was deployed in the Aubers- Fromelles sector and in the Battle of Fromelles (19/20 July 1916). In the Battle of the Somme on October 5, 1916, Hitler was wounded by a shrapnel on his left thigh near le Barqué ( Ligny-Thilloy ), which later led to numerous speculations about a possible monarchy . He was nursed to health in the club hospital in Beelitz (Potsdam) until December 4th and then stayed in Munich for care. Later he wanted to have noticed the dwindling enthusiasm for war in Germany for the first time there.

On March 5, 1917, Hitler returned to his old unit, which had meanwhile been relocated to Vimy . In spring he took part in the Battle of Arras , in summer in the Third Battle of Flanders , from the end of March 1918 in the German spring offensive and in the decisive second battle on the Marne . In May 1918 he received a regimental diploma for outstanding valor and the wound badge in black. On August 4th he received the Iron Cross 1st Class for reporting to the front after all telephone lines had failed. The regimental adjutant Hugo Gutmann , a Jew, had promised him this award for this; the division commander approved it after two weeks. Hitler later denied having worn the Iron Cross First Class in World War I, as it was also awarded to the Jew Gutmann (Hitler: “a cowardly special equals”). On August 21, 1918, Hitler left the regiment, which was involved in heavy fighting, for a week-long telephone operator course in Nuremberg , and then went on his regular home leave in Berlin . While he kept referring to his impressions in Berlin later on, he kept silent about his probably first visit to the future city of the Nazi party rallies, which gave rise to speculation about connections with his superior Gutmann, who came from Nuremberg. On September 27th he returned to the Western Front, where his regiment was meanwhile affected by the disintegration that had begun on the entire Western Front with the Black Day of the German Army on August 8th.

On the morning of October 14, 1918, Hitler was caught in a mustard gas attack on a bulletin board at Wervik in Flanders, which he also described in Mein Kampf . If the poison got into the eyes, the eyelids swelled quickly with severe pain, which led to functional blindness. If there were no complications, the symptoms often subsided completely after a few weeks, as with Hitler. Those wounded in this way were considered "slightly wounded". With this classification, Hitler was admitted to the Pasewalk reserve hospital, a convalescent home for the slightly injured, under the number 7361 with the diagnosis “gas poisoned” . Usually the convalescence stay lasted four weeks. On November 19, Hitler went to the reserve battalion of the 2nd Bavarian Infantry Regiment in Munich as "fit for use in the war".

In Pasewalk on November 10, Hitler learned of the November Revolution and the armistice negotiations at Compiègne , which he received with deep indignation. Later (1924) he described these events in the sense of the stab- in-the-back legend as the “greatest disgrace of the century”, which led him to decide to become a politician. The latter is considered untrustworthy, since Hitler had almost no means and no prospects at the time, had no contact with politicians and never mentioned the alleged decision until 1923.

According to contemporary witnesses, Hitler behaved obsequiously to officers. “Respect your superiors, don't contradict anyone, blindly submit,” he stated in court in 1924 as his maxim. He never complained of bad treatment as a soldier and thus separated himself from his comrades. That is why they insulted him as a “white raven”, as someone who thought he was something special or who held an opinion that differed from the majority. According to her statements, he did not smoke or drink, never talked about friends and family, was not interested in going to brothels and often sat for hours reading, thinking or painting in a corner of the shelter.

The National Socialists Fritz Wiedemann and Max Amann claimed after 1933 that Hitler had refused a military promotion for which he would have been considered as a multiple wounded and a bearer of the Iron Cross, first class. Later praise of Hitler's alleged comradeship and bravery from comrades in the war is considered untrustworthy, as the NSDAP rewarded them with functionaries and money.

According to his letters from the field, Hitler disapproved of the spontaneous Christmas peace in 1914 . On February 5, 1915, he described the fighting in detail and concluded by saying that he hoped for the final settlement with the enemies inside. German war crimes such as arson and mass shootings in retaliation for alleged sabotage that had been committed in occupied Belgium in 1914 were clearly exaggerated by Hitler in retrospect in September 1941 after the start of the Russian campaign and described them as an exemplary method of fighting partisans in the east.

Sebastian Haffner called Hitler's experience at the front his “only educational experience”. Ian Kershaw judged: "The war and its aftermath created Hitler." Since Hitler devoted himself entirely to one cause for the first time in his life, the war, the prejudices and phobias he had already brought with him were decisively increased in the bitterness over the war defeat from 1916 onwards . Thomas Weber judges against it: "Hitler's future and his political identity were still completely open and malleable when he returned from the war."

Political advancement (1918–1933)

Propaganda speaker of the Reichswehr

On November 21, 1918, Hitler returned to the Oberwiesenfeld barracks in Munich. He tried to avoid the demobilization of the German Army and therefore remained a soldier until March 31, 1920. During this time he formed his political worldview, discovered and tested his demagogic speaking talent.

From December 4, 1918 to January 25, 1919, Hitler and 15 other soldiers guarded around 1,000 French and Russian prisoners of war in a camp in Traunstein run by soldiers' councils . On February 12th he was transferred to the second demobilization company in Munich and on February 15th he was elected as one of the stewards of his regiment. As such, he worked with the propaganda department of the new Bavarian state government under Kurt Eisner ( USPD ) and was supposed to train his comrades in democracy . On February 16, he and his regiment therefore took part in a demonstration by the “Revolutionary Workers' Council” in Munich. Historians are divided on whether Hitler accompanied the funeral procession for Eisner, who was murdered five days earlier, on February 26, 1919, as a blurred photo is supposed to prove.

On April 15, Hitler was elected to the replacement battalion council of the soldiers' councils of the Munich Soviet Republic , which had been proclaimed on April 7th. After their violent suppression in early May 1919, he denounced other shop stewards from the battalion council before a court martial of the Munich Reichswehr administration as "the worst and most radical agitators [...] for the Soviet republic", thus contributed to their conviction and bought the goodwill of the new rulers. He later kept silent about his previous collaboration with the socialist soldiers' councils. This is usually seen as opportunism or as evidence that Hitler could not have been a pronounced anti-Semite until then. Unlike other members of his regiment he joined none of the established against the Soviet Republic volunteer corps to.

In May 1919, Hitler first met Captain Karl Mayr , head of the "reconnaissance battalion" in the Reichswehr Group Command 4. This may recruited him shortly thereafter as an undercover agent . On the recommendation of his superiors, in the summer of 1919 he took part in two “ anti-Bolshevik education courses” for “propaganda among the troops” at the University of Munich . He was trained for the first time by German national, Pan-German and anti-Semitic academics such as Karl Alexander von Müller , who discovered Hitler's talent as a speaker, and Gottfried Feder , who had coined the catchphrase of “breaking interest bondage”. By meeting Feder, wrote Hitler during his imprisonment in Landsberg, he found “the way to one of the essential prerequisites for founding a new party”.

From July 22nd, Hitler was supposed to re-educate soldiers allegedly “contaminated” by Bolshevism and Spartacism in the Reichswehr camp Lechfeld with a 26-man “reconnaissance command” from the Munich garrison . His speeches aroused strong emotions, including anti-Semitic remarks. In the spring or autumn of 1919, Mayr introduced him to Ernst Röhm , the co-founder of the secret, right-wing extremist officers' association " Iron Fist ".

Mayr's informants were supposed to monitor new political parties and groups in Munich. To this end, Hitler first attended a meeting of the German Workers' Party (DAP) on September 12, 1919 . There he violently contradicted the discussed secession of Bavaria from the Reich. The party chairman Anton Drexler invited him to join the party because of his eloquence. On September 16, he wrote an “Expert Opinion on Anti-Semitism” for Mayr for Adolf Gemlich, a participant in the Lechfeld courses. In it he emphasized that Judaism was a race , not a religion . “For the Jew”, “religion, socialism, democracy [...] are only a means to an end, to satisfy greed for money and power. The consequences of his work will lead to racial tuberculosis of the peoples. ”Therefore, the“ anti-Semitism of reason ”must systematically and lawfully combat and eliminate its prerogatives. “His ultimate goal, however, must be the removal of the Jews in general. Only a government of national force is capable of both of these things [...] only through the ruthless use of nationally-minded leaders with an inner sense of responsibility. "Mayr largely agreed with Hitler's remarks.

Promotion to leader of the NSDAP

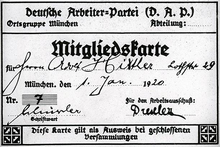

Hitler joined the DAP in September 1919. Contrary to his claim in Mein Kampf , he was not the seventh member of the party, but of the party's working committee as an advertising chairman . In the first surviving list of party members from February 2, 1920, he bears the number 555, which does not make him the 555th member, because the list begins with the number 501 and is also in alphabetical order. From autumn 1919 the anti-Semitic writer Dietrich Eckart influenced Hitler's thinking, brought him into contact with the Munich bourgeoisie and important donors, promoted him as a right-wing agitator among social lower classes and propagated him from March 1921 as the future charismatic “ leader ” and savior of the German nation. From him, who was considered his mentor, Hitler took over the conspiracy theory of an alleged world Jewry that was behind both US high finance and "Bolshevism" until 1923 .

When the DAP was renamed the NSDAP on February 24, 1920, Hitler presented the 25-point program that he, Drexler and Feder had written . On March 16, 1920, Eckart introduced him to some of the initiators of the Kapp-Lüttwitz Putsch in Berlin , which collapsed the following day. On another visit to Berlin in 1920, Hitler met Heinrich Claß ( Pan-German Association ), who then supported him financially and pushed ahead with the expansion and debt relief of the party newspaper Völkischer Beobachter .

When he was discharged from the Reichswehr (April 1, 1920), Hitler was able to live on his speaking fees. At that time it reached 1200 to 2500 listeners per appearance and recruited new members for the NSDAP, with which the German National Guard and Defense Association (DVSTB) and the German Socialist Party (DSP) were still competing strongly. He stopped Drexler from uniting the NSDAP with the DSP and continued on 7/8. August an alliance with the Austrian DNSAP in Salzburg to underline the Pan-German claim of his party.

In his keynote address Why are we anti-Semites? On August 13, 1920, Hitler explained his ideology in more detail for the first time: All Jews are incapable of constructive work because of their allegedly unchangeable racial character. They are essentially parasites and do everything to achieve world domination , including (so he claimed) racial mixing, dumbing down the people through art and the press, promoting the class struggle up to and including trafficking in girls . In doing so, he made racist anti-Semitism the main feature of the NSDAP program.

With a long raincoat over his suit, a "gangster hat", a conspicuously visible revolver and a dog whip , Hitler drew attention to himself at receptions in Munich. Supporters described him as a “grandiose popular speaker” who “outwardly somehow appeared between sergeant and clerk, with deliberate awkwardness and at the same time so much eloquence [...] in front of a mass audience”. Hitler transformed the SA from a "hall protection force" into a paramilitary thug and intimidation force of the NSDAP. He designed swastika flags and standards for power demonstrations by the SA in town and country.

In June 1921 he was in Berlin again to raise funds for his party. The NSDAP Munich invited Otto Dickel , a social reform party member from Augsburg, as a substitute speaker and arranged a meeting on July 10, 1921 with Nuremberg DSP delegates to negotiate a merger. Hitler, whom Hermann Esser might have informed, appeared. When Eckart, Drexler, and others welcomed Dickels' proposals for program reform, he left the meeting furious. On July 11th he resigned from the NSDAP, perhaps because he feared losing his special position in the party. On July 14th, he sharply criticized Dickel and his views in a detailed statement. For his re-entry, which Dietrich Eckart brokered, he demanded dictatorial powers in the NSDAP. On July 29, 1921, a general meeting decided on statutes with the required “dictatorial principle”, gave Hitler the leadership of the party and excluded Drexler as “honorary chairman” from the decision-making process. Hitler's confidante Amann streamlined and centralized the party organization. This is how Hitler asserted his claim to leadership and prevented the party from turning to the left. He was now a local party leader supported by many nationalists, opponents of democracy and militarists among intellectuals, in the government and administration of Bavaria.

In order to expand his influence, he made a few speeches in front of the Berlin National Club from 1919 and in Austria from 1920 onwards . He wanted to become better known through targeted attacks on political opponents. On September 14, 1921, he and his supporters violently disrupted an event of the separatist Bayernbund in Munich's Löwenbräukeller . Its founder Otto Ballerstedt was seriously injured and reported him. On January 12, 1922, Hitler was sentenced to three months' imprisonment for violating the peace and assaulting himself. He was serving a month of it in Stadelheim ; the remainder of the sentence was suspended until 1926 . In the later " Röhm Putsch " (1934) Hitler had Ballerstedt murdered.

Some British and US press articles rated him at the time as “potentially dangerous”, as a representative of an “army of vengeance” or as a “German Mussolini ”. Hitler had himself proclaimed as such by Hermann Esser in Munich on November 3, 1922, three days after Mussolini's successful march on Rome .

coup attempt

During the Kapp Putsch in 1920, the Reichswehr leadership in Bavaria forced the coalition government Hoffmann to resign. The new government under Gustav von Kahr took a right course to turn Bavaria into the “ regulatory cell ” of the empire. She gave support and shelter to many militant right-wing extremists such as Hermann Ehrhardt . After the dissolution of the Freikorps in the same year, they organized themselves into armed “ resident brigades ” and “patriotic associations”, which sought to overthrow the Weimar Republic . Some of them affirmed and committed political or femicide .

In March 1922, the Christian-conservative Bavarian Minister of the Interior, Franz Xaver Schweyer , invited the chairmen of the most important parties represented in the Bavarian state parliament to a meeting in order to have Hitler, who was reported as " stateless ", deported from Bavaria. The representatives of the bourgeois parties agreed to Schweyer's proposal, only the SPD parliamentary group leader Erhard Auer was against it. The other parties gave in to Auer and therefore Hitler was not expelled from the country.

After the Allies had forced the dissolution of the Bavarian Resident Guard in 1921, Kahr entrusted Otto Pittinger with the secret continuation of the "military work". In August 1922, Pittinger, the Munich police chief Ernst Pöhner and Ernst Röhm planned a putsch based on a planned mass rally by the patriotic associations against the Republic Protection Act on August 25. However, this was banned for a short time, so that only a few thousand National Socialists gathered. Hitler, who knew the putsch plan, is said to have foamed with rage and announced that he would act next time. The radical forces around Röhm and Ludendorff rejected Pittinger's monarchist-federalist course and increasingly resisted his attempts to unite the defense movement. The NSDAP initially joined the "Association of Patriotic Associations in Bavaria" founded on November 9, 1922, but not the Bund Oberland and the Bund Wiking . In February 1923, during the occupation of the Ruhr , the working group of the patriotic combat units was founded on Röhm's initiative , which the NSDAP and SA joined. In it Hitler exercised significant influence and defined as its goals: “1. Achievement of political power, 2. Brutal cleansing of the fatherland from its internal enemies, 3. Education of the nation, spiritually by will, technically through training for the day that gives freedom to the fatherland, ending the period of November betrayal and our sons and leaves a German empire to grandchildren again. [...] “After several ethnic politicians, including Hitler, received court summons for violating the Republic Protection Act, in April 1923 the working group asked the Bavarian state government to reject arrest warrants against“ patriotic men of Bavaria once and for all ”. His influence increased when he disconnected the SA from its association with Ehrhardt's organization.

Hitler was the first to call for a "national May Day celebration". However, the traditional, officially approved demonstration by the left-wing parties on May 1st , 1923 in Munich could not be prevented. This weakened Hitler's authority in the NSDAP, so that he withdrew from the public for a while. In May 1923 he founded a guard of bodyguards and thugs with the Adolf Hitler Munich raiding party made up of close confidants.

At the " German Day " on September 1 and 2, 1923 in Nuremberg, Hitler, Ludendorff and their supporters united the Bund Oberland with the Bund Reichskriegsflagge under Röhm and the SA to form the German Combat League . He called for a “national revolution”, which, because of the experience of May 1st, was primarily about taking possession of the “police power of the state”. On September 25, Hitler took over his political leadership. During a stay in Zurich arranged by Ulrich Wille junior in August 1923, he spoke to invited guests “On the situation in Germany” and received donations between 11,000 and 123,000 francs, mostly in cash and without a receipt. It is unclear whether the unknown total sum made it possible for the NSDAP to prepare for a coup.

On September 26, the new Chancellor Gustav Stresemann ( DVP ) canceled passive resistance against the Belgian-French occupation of the Ruhr. Thereupon the Bavarian government declared a state of emergency over Bavaria according to Article 48 and transferred the executive power with the rank of “General State Commissioner ” to Gustav von Kahr. With his “special relationships” to Bavarian right-wing extremist organizations and his well-known ethnic-anti-Semitic sentiments, he should officially prevent “stupidities” from “any side”. As one of his first measures, he had Eastern Jewish families from Bavaria deported and their property confiscated.

An article entitled Die Diktatoren Stresemann - Seeckt in the Völkischer Beobachter , which sharply attacked the Reich government, escalated the conflict between it and the government of Bavaria. Reichswehr Minister Otto Geßler , who had executive power over the entire Reich on September 27th, after the state of emergency was imposed, thereupon banned the Völkischer Beobachter . Kahr and the commander of the Reichswehr in Bavaria, Otto von Lossow , refused to accept this order. On September 29, Kahr declared that he would no longer enforce the Republic Protection Act in Bavaria.

Hitler visited the Villa Wahnfried for the first time on September 30th . The “Bayreuth Circle” around Cosima Wagner supported his putsch plan and his claim to become the longed-for national “leader”. On October 7, he tried in vain to persuade Lossow and Seisser to join his combat league.

On October 20, Gessler deposed Lossow. Kahr then demonstratively appointed Lossow "State Commander" and had the 7th Reichswehr Division stationed in Bavaria sworn in on Bavaria. This open breach of the constitution was a first step towards Bavaria's separation from the Reich. After the SPD left the Stresemann cabinet on November 2, 1923, Reich President Friedrich Ebert called on November 3, analogous to the execution of the Reich against Saxony, which was co-ruled by communists, to use Reichswehr troops against Bavaria. The chief of the army command, Hans von Seeckt , refused, because the army did not have sufficient forces and the Reichswehr was not marching against the Reichswehr. Seeckt condemned the disobedience of the Bavarian Reichswehr troops, but let Kahr know that he had adhered to the constitutional forms primarily in the interests of the unity of the Reich. At the same time he warned Kahr and Lossow not to orientate themselves too much towards the ethnic and national extremists. Seeckt was also intended by representatives of heavy industry such as Hugo Stinnes and at times by politicians such as Ebert and Stresemann as a possible “emergency chancellor” of a national dictatorship.

The “Bavarian Triumvirate” Kahr, Lossow and the head of the Bavarian State Police, Colonel Hans von Seisser , were considering putsch plans against Berlin. In consultation with contacts in northern Germany, they hoped in October 1923 to use military pressure to induce the Reich government to set up a “national directory”. At a meeting with the leaders of the paramilitary groups on October 24, Lossow even spoke of a “march on Berlin”, but actually played mainly against the German Combat League for a while. At the beginning of November, however, there was still complete uncertainty about the possible composition of the board of directors. While Kahr was under discussion as Reich President, Hitler and Ludendorff, who wanted a directory under their leadership in Munich, would not have been involved in any case. On November 3, Seeckt stated to Seisser that he did not want to do anything against the legitimate government.

After November 3, Kahr warned all leaders of "patriotic associations" against unauthorized actions and refused to meet with Hitler. He feared Kahr's agreement with the Reich government and therefore arranged an imminent putsch on November 7th with the other Kampfbund leaders. On the evening of November 8th, he had a gathering of around 3,000 Kahr's supporters in the Munich Bürgerbräukeller surrounded by his Kampfbund, gained access by force of arms, proclaimed the “national revolution” and forced Kahr, Seißer and Lossow at gunpoint, a “provisional one German national government ”under his leadership. He had all members of the Bavarian state government arrested and appointed Ludendorff commander in chief of the Reichswehr. This released the triumvirate, which revoked the extorted consent a few hours later and began to prepare for the crackdown on the coup. The SA and Bund Oberland arrested numerous real or supposed Munich Jews, whose names and addresses were taken from telephone books, as hostages. Although the Munich company commander Eduard Dietl , an early DAP member and trainer of the SA, and the offspring of officers refused to give orders to take action against the putschists, the combat alliances led by Ernst Röhm were able to manage most of the Munich barracks, the train station and important ones on the night of November 9th Do not occupy government buildings. Thereupon Hitler and Ludendorff tried with a march of up to 4,000 partly armed NSDAP supporters to force the overthrow in Munich. The state police under Seisser stopped this march near the Feldherrnhalle . In a short firefight, 15 coup officers and 4 police officers as well as one bystander died. Hitler, injured in a fall, fled and was arrested on November 11 in Ernst Hanfstaengl's house on the Staffelsee . The NSDAP, which had already been banned in nine German states, was also banned across the Reich in Bavaria and on November 23rd.

In spite of his refusal to give orders, Ebert had given Seeckt the supreme command of the Reichswehr on November 8, 1923, so that he could move the Bavarian Reichswehr to take action against the putschists. Hitler's and Ludendorff's solo effort made the 7th Division cohesive with the rest of the Reichswehr, and thwarted and discredited the putsch plans of Kahr and Seeckt. Hitler learned from this that he could gain power “not in total confrontation with the state apparatus, but only in calculated cooperation with it” and that to do so, he had to maintain the “appearance of legality ”.

The amateurishly staged, failed coup attempt was reinterpreted as a triumph from 1933 and celebrated annually as a heroic act with the commemoration of the " martyrs of the movement".

Trial and imprisonment

From February 26, 1924 , a trial against ten coup participants took place before the Bavarian People's Court , not the competent Reichsgericht in Leipzig. An interrogation protocol exonerated Ludendorff despite months of active preparations for a coup: he knew nothing about the coup plan. Apparently, Hitler dared to portray himself as the driving force behind the putsch plan from the start, denied the charge of high treason and claimed that the “ November criminals ” of 1918 were the real traitors. In doing so, he accepted the offer of the presiding judge Georg Neithardt for a mild verdict in case he withheld the putsch plans of the Kahr, Lossow and Seißer summoned as witnesses. The hostage-taking and killing of the four police officers were not grounds for charge or the subject of the trial. The “judicial comedy” ended with an acquittal for Ludendorff and mild sentences against five co-defendants for aiding and abetting high treason.

Judge Neithardt, who had already led the first trial against Hitler in 1922 and therefore knew that the prison sentence at that time was still suspended, sentenced Hitler in an act of perversion of justice to a minimum of five years imprisonment and a fine of 200 gold marks . In addition, the court refused his expulsion as a criminal foreigner, as required by the Republic Protection Act, because he had an "honorable disposition", thought and felt German, had been a voluntary soldier in the German army for four and a half years and had been wounded in the process.

During his detention, Hitler enjoyed numerous privileges in a separate wing of the Landsberg am Lech prison ; he had close contact with fellow convicts and was allowed to receive many visitors and have confidential conversations with them. Visitors referred to his cell as a “delicatessen shop” because of the many delicatessen items.

Prosecutor Ludwig Stenglein contradicted an early release : future good behavior was not to be expected because of his violations of imprisonment conditions (mail smuggling, writing of Mein Kampf, etc.). Nevertheless, he was released on December 20, 1924 after less than nine months in prison for allegedly good conduct.

Up until the trial, Hitler saw himself more as a “drummer” of the völkisch movement who was supposed to clear the way for another “savior of Germany” like Ludendorff. The trial reports made him known in northern Germany as the most radical “völkisch” politician. His followers venerated him as a hero and martyr for the national cause. This strengthened his position in the NSDAP and his reputation among other nationalists. Because of this approval, the propaganda success of his defense, his reflection when writing Mein Kampf and the disintegration of the NSDAP during his imprisonment, Hitler saw himself in the role of the great leader and savior of Germany that many had hoped for. After his dismissal, he wanted to rebuild the NSDAP as a tightly organized leader party independent of other parties .

ideology

During his imprisonment in 1923/24, largely without outside help, Hitler wrote the first part of his program Mein Kampf . He did not intend an autobiography or a replacement for the 25-point program. Here he developed his racial anti-Semitism, which has been represented since the summer of 1919, with the political goal of "removing the Jews in general". The central idea was a race war that determined the history of mankind and in which the “right of the fittest” would inevitably prevail. He understood the "large unmixed population of Nordic-Germanic people" in the "German national body ", which he refers to the racial ideology of Hans FK Günther as the strongest race destined for world domination. Hitler saw the Jews as the mortal enemy of the Aryans in the world history: They too were striving for world domination, so that there would have to be an apocalyptic final battle with them. Because they had no power and nation of their own, they tried to destroy all other races as a “parasite in the body of other peoples”. Since this endeavor was inherent in their race, the Aryans could only preserve their race by exterminating the Jews. In the last chapter of the second volume of Mein Kampf he wrote about German Jews : “If at the beginning and during the war twelve or fifteen thousand of these Hebrew corrupters of the people had been kept under poison gas like hundreds of thousands of our very best German workers from all walks of life Fields had to endure, then the millions of victims of the front would not have been in vain. On the contrary: Eliminated twelve thousand villains at the right time would have saved the lives of perhaps a million decent Germans who would be valuable for the future. ”This proves Hitler's willingness to commit genocide, not his planning.

The programmatic conquest of Lebensraum in the East was aimed at the "annihilation of ' Jewish Bolshevism '", as he called the system of the Soviet Union , and the "ruthless Germanization" of Eastern European areas. What was meant was the settlement of Germans and expulsion ("evacuation"), extermination or enslavement of the local population. He strictly rejected cultural-linguistic assimilation as " bastardization " and ultimately self-destruction of his own race. With this he had, according to Kershaw, "created a solid intellectual bridge between the 'extermination of the Jews' and a war against Russia aimed at the acquisition of ' living space '". On this ideological basis, Eastern Europe up to the Urals was to be forcibly developed “as a supplementary and settlement area” for the National Socialist German Reich. Hitler's idea of living space tied in with Karl Haushofer's theories of geopolitics and surpassed them by making the conquest of Eastern Europe the primary war goal of the NSDAP and a means for lasting economic autarky and hegemony in Germany in a thoroughly reorganized Europe .

Hitler's racism led to his devaluation of everything “weak” as inferior life without a right to life: “The stronger has to rule and not merge with the weaker in order to sacrifice his own greatness.” Outwardly, he assessed the Slavs as an “inferior race “That is incapable of forming states and therefore can be ruled by higher-quality Germans in the future. Inwardly, he called for compulsory sterilization of fertile hereditary diseases , human breeding and “euthanasia” . So he said at the Nuremberg NSDAP party congress in 1929: "If Germany had a million children a year and 700,000 to 800,000 of the weakest were eliminated, the result might even be an increase in strength in the end." These ideas go back to representatives of German-speaking racial hygiene such as Alfred Ploetz and Wilhelm Schallmayer back. They mainly affected people with disabilities . Hitler's notion of the “alien”, “ anti-social ” or “degenerate” also affected unnamed groups in Mein Kampf , such as “ Gypsies ” (meaning: Roma and Yeniche ), homosexuals and Christian pacifists such as the Jehovah's Witnesses , whom Hitler strayed as idealistic and therefore devalued politically dangerous refusers of the necessary struggle for survival. From 1933 the National Socialists murdered many members of these groups.

Against democracy, the separation of powers , parliamentarism and pluralism, Hitler set an unlimited leader principle : all authority in party and state should come from an unelected "leader of the people" who was only confirmed by acclamation. The latter should appoint the subordinate leadership level, which in turn should appoint the next lower level. The respective “followers” should obey blindly and unconditionally. This leader idea had arisen in modern nationalism since 1800 and since 1900 it became common property in the anti- democracy camp as a yearning for a “people's emperor” or an authoritarian, bellicose chancellor like Otto von Bismarck . Hitler had got to know them in Linz as a cult around Georg von Schönerer and in Vienna experienced the effect of anti-Semitic popular speeches by Karl Lueger , whom he now highlighted as a model for a “tribune of the people”. The paramilitary organization of the NSDAP corresponded to the leader principle. He claimed the role of national leader from November 1922 after Mussolini's successful march on Rome and took over the associated “leadership cult” and a voluntaristic understanding of politics from Italian fascism . Accordingly, he claimed that he had acquired his ideology in Vienna as an autodidact until 1913 and that this “granite foundation” of his actions has hardly changed since then. Schönerer and Lueger would have opened his eyes to the " Jewish question " and taught him to regard the Jews in all their forms as a foreign people; but through his own research he recognized the identity of Marxism and Judaism and thus condensed his instinctive hatred into a " world view " until 1909 .

Despite the rejection of the official churches, which he sought to subordinate himself to as competition on the ideological and organizational level, Hitler remained a member of the Roman Catholic Church throughout his life . Rhetorically he professed himself to be a personal God , whom he called “ Almighty ” or “ Providence ” and understood as a force at work in history. He created the German people, determined them to rule over the peoples and selected individuals like himself to be his leaders. In doing so, he transferred the biblical election of the people of Israel to Germanness and integrated it into the racist worldview of National Socialism. For this he claimed sole and total validity in politics. The philosopher Hermann Schmitz characterizes Hitler in Adolf Hitler in the Story (1999) as anti-Christian. As evidence, he cites inter alia. Joseph Goebbels ' diary entry of April 8, 1941: “The Führer is a person who is completely oriented towards antiquity . He hates Christianity because it has crippled all noble humanity. ”According to the NSDAP program, which affirmed a non-denominational“ positive Christianity ”against the“ Jewish-materialistic spirit ”within the framework of the“ morality of the Germanic race ” Hitler's political anti-Semitism to the will of God and to which any executor: "So I think today in the sense of the Almighty Creator to act: As I defending myself against the Jew, I am fighting for the Lord's work." this " redemptive anti-Semitism" kept it up to his suicide unchanged and highlighted him again and again as the core of his thinking. From the failure of the “Los-von-Rome” movement of Schönerer, he concluded: National Socialism must respect and protect both major churches and their teachings as “valuable pillars for the existence of our people” and combat denominational party politics. Devout Protestants and Catholics could participate in the NSDAP without any conflicts of conscience. Schöneer's fight against the church disregarded the people's soul and was tactically wrong, as was Lueger's mission to the Jews , instead of striving for a solution to the “vital question of humanity”. He only praised Gottfried Feder as an influence after 1918.

Since Hitler adopted almost all of his ideas from anti-Semitism, social Darwinism and pseudoscientific biologism of the 19th and 20th centuries, his ideology and his rise are not classified as an exception, but rather as a component and result of these currents. The equation of Social Democrats, Marxists and Jews in Austria-Hungary was common among Christian Socialists, German Nationalists and Bohemian National Socialists since the 1870s. Many individual motifs of his early lectures, such as the alleged nomadism of the Jews and their alleged inability to art, culture and state formation, Hitler took from many new publications of German anti-Semites, which he borrowed from the Munich National Socialist Friedrich Krohn in 1919/20 . Among them were H. Naudh ( The Jews and the German State , 12th edition 1891), Eugen Dühring ( The Jewish question as a question of racial character , 5th edition 1901), Theodor Fritsch ( Handbook on the Jewish question , 27th edition 1910), Houston Stewart Chamberlain ( The foundations of the 19th century , 1899), Ludwig Wilser ( Die Germanen , 1913), Adolf Wahrmund ( The law of nomadism and today's Jewish rule , Munich 1919) and the German translation of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion by Ludwig Müller von Hausen had published in 1919. Hitler used the "protocols" as he did before him pen as evidence of the alleged "Jewish world conspiracy".

The first volume of Mein Kampf sold about 300,000 copies from 1925 to 1932 and was widely known through many reviews in public conflicts. However, almost only Hitler's foreign and party political goals were taken into account, not his racial theory. Almost no leading foreign politician read the book. The second volume, The National Socialist Movement , published in 1926, elaborated on Hitler's ideas about foreign policy, the tasks and structure of the NSDAP and received even less attention. Hitler's Second Book from 1928 elaborated on his extreme anti-Semitism, racism and his population policy plans, but remained unpublished.

In order to expose the National Socialists as implausible hypocrites, political opponents emphasized the contradiction between Hitler's racial ideal and his appearance. Fritz Gerlich, for example, cited a “report” by the “racial hygienist” Max von Gruber from 1923 (“Face and head bad race, mixed breed…”) in the Catholic newspaper Der straight way in 1932 and came up with that based on the race criteria of Hans FK Günther Result, Hitler belongs to an "Eastern-Mongolian racial mixture". It was mainly because of this criticism that Gerlich was murdered in 1934. Even Kurt Tucholsky called Hitler in 1932 as "vagabond Mongols wenzel ". The criticism of Hitler's cult and Nazi ideology lived on after 1933 as a life-threatening whisper joke : "Blond like Hitler, tall like Goebbels, slim like Göring and chaste like Röhm."

New establishment and first successes of the NSDAP

On January 4, 1925, Hitler promised Bavaria's Prime Minister Heinrich Held that he would only pursue politics in a legal way and help the government in the fight against communism . Thereupon Held lifted the NSDAP ban on February 16, 1925. With an editorial in the Völkischer Beobachter on February 26, Hitler re-founded the NSDAP under his leadership. So that his party headquarters could control the admission, all previous members had to apply for a new membership card. At the same time he appealed to the unity of the völkisch movement in the fight against Judaism and Marxism, not against Catholicism, which is strong in Bavaria . In doing so, he distinguished himself from Ludendorff, who resigned the chairmanship of the National Socialist Freedom Movement on February 12 and thus initiated its dissolution. Hitler managed to get the competing splinter groups, the Großdeutsche Volksgemeinschaft , “German Party”, “ Völkisch-Sozialer Block ” and the Deutschvölkische Freedom Party that arose during the NSDAP ban to rejoin or re-join the NSDAP. He only admitted the SA as an auxiliary force of the NSDAP, no longer as an independent paramilitary organization, so that Ernst Röhm gave up its leadership.

Hitler had a black Mercedes borrowed from Jakob Werlin , his own chauffeur and a bodyguard with which he drove to his performances. From then on, he staged it down to the last detail by choosing the time of his arrival, his entering the event room, the speaker's stage, his clothing for the intended effect and rehearsing his rhetoric and facial expressions. At party meetings he wore a light brown uniform with a swastika band, a belt, a leather strap over his right shoulder and knee-high leather boots. In front of a larger audience he wore a black suit with a white shirt and tie "when it seemed appropriate [...] to present a less martial, more respectable Hitler". With his often worn blue suit, lederhosen, raincoat, felt hat and dog whip, on the other hand, he looked like an "eccentric gangster". In his free time he preferred to wear traditional Bavarian lederhosen. In midsummer he avoided being seen in bathing trunks so as not to be ridiculous.

Hitler founded in April 1925 in Munich with the Schutzstaffel (SS), a subordinate to the party personal "life annuities and beatings Guard", which from the Nazi Party was subject in 1926 of the SA. At first he successfully operated the nationwide expansion of the NSDAP by founding new local and regional groups, for which he appointed " Gauleiter ". Regional bans on speaking hardly hindered this work. In March 1925 he commissioned Gregor Strasser to build up the NSDAP in North and West Germany. Up until September 1925, Strasser formed its own wing there, advocating stronger socialist goals, a social revolutionary course and foreign policy cooperation with the Soviet Union in relation to Hitler's Munich party headquarters. Strasser's draft of a new party program called for land reform, the expropriation of stock corporations and the participation of the NSDAP in the referendum on the expropriation of princes . Hitler initially let him go, but won Strasser's follower Joseph Goebbels as a supporter of his course and his leadership role. In February 1926 he pushed through against Strasser's wing the rejection of the new draft program and thus also of his demand for the expropriation of the princes as a form of a "Jewish system of exploitation". Hitler forbade any discussion of the party program (from 1920). In the summer of 1926, the NSDAP introduced the Hitler salute , making the Hitler cult its central feature. At that time, Hitler ruled the party in a manner similar to that from 1933 onwards, initially allowing arguments and rivalries and then pulling the decision. The personal bond with the “Führer” became decisive for the influence that a functionary had in the party, and Hitler became almost invulnerable in the NSDAP.

Ever since his promise of legality, Hitler wanted to defeat and undermine democracy at its own weapon. The NSDAP should move into the parliaments without cooperating constructively there. In addition, the SA should generate public attention for the party and its leader with spectacular marches, street battles and riots and at the same time reveal the weakness of the democratic system. For this purpose, the NSDAP used the then completely new methods of advertising and influencing the masses (→ Nazi propaganda ). Hitler's mass-produced rhetoric was fundamental to their success. He took up current political issues in order to regularly and specifically talk about the “guilt of the November criminals of 1918”, their “stab in the back”, the “Bolshevik danger”, the “shame of Versailles”, the “parliamentary madness” and the root of all evil : "The Jews". With his Ruhr campaign and the brochure Der Weg zum Wiederaufstieg he tried to win support from the Ruhr industry. In the 1928 Reichstag election , however, the NSDAP remained "an insignificant, albeit vocal splinter party," with 2.6 percent of the vote. The stabilized economic conditions and the sustained economic upswing (" Golden Twenties ") offered radical parties little opportunity to agitate until 1929.

The referendum initiated jointly by the NSDAP and DNVP in 1929 against the Young Plan , which was supposed to settle the open reparation issues between Germany and its former opponents of the war, failed. But Hitler and his party received substantial approval from the nationalist-conservative bourgeoisie for the first time in the state elections in Thuringia in autumn 1929. From then on, the press empire of DNVP chairman Alfred Hugenberg also supported Hitler because he saw in him and the NSDAP controllable means to help the German national forces establish a mass base.

As a result of the global economic crisis that began in 1929, the Weimar coalition broke up in Germany on March 27, 1930 . The Chancellor Hermann Müller (SPD), who was a democratically-minded majority in the Reichstag had and the first presidential cabinet of Heinrich Brüning ( Center ) followed the general election 1930 : The Nazi Party increased its vote share to 18.3 percent, and its parliamentary seats from 12 to 107 MPs . As the second strongest party, it had become a relevant power factor in German politics.

During the Reichswehr trial in Ulm on September 25, 1930, Hitler swore as a defense witness that he would “under no circumstances strive for his ideal goals by unlawful means” and that party members who did not adhere to this requirement would be excluded. Then he threatened: “If our movement wins in its legal struggle, a German state court will come; and November 1918 will find its atonement , and heads will roll. ”During a testimony in 1931 , attorney Hans Litten revealed that Hitler had continued to allow Nazi propaganda for a violent overthrow, thereby breaking his oath of legality. Hitler was charged with perjury . Although there was enough evidence to expel him, the case was delayed and dropped.

Meanwhile, Chancellor Briining tried to persuade Hitler to cooperate and offered him participation in the government as soon as he, Briining, had resolved the question of reparations . Hitler refused, so that Brüning had to let the SPD tolerate his minority cabinet .

Path to Chancellorship

Since 1931, Reich President Hindenburg was "almost inundated" with lists of signatures and entries for Hitler's Reich Chancellor. He invited Hitler and Hermann Göring for a first conversation on October 10, 1931, the day before the meeting of the " Harzburg Front ". According to Hitler's biographer Konrad Heiden , Hitler held monologues instead of answering Hindenburg's questions. He is said to have said to Kurt von Schleicher that the “Bohemian private” (Hindenburg probably confused the Austrian Braunau with the Bohemian town of the same name , Czech Broumov , which he had met in 1866 as a lieutenant on the way to the battle of Königgrätz ) could “at most Minister of Post ”. Hitler impressed him, but did not convince him of his suitability for the Chancellery.

In the crisis year of 1932, the conservative politicians Franz von Papen , Kurt von Schleicher, Alfred Hugenberg and Oskar von Hindenburg acted on Hindenburg with various personal goals, some with one another, some against one another. They all wanted to replace the Weimar democracy with an authoritarian form of government and initially rejected Hitler and his party as "plebeian". Because they received little support from the population, they increasingly viewed and promoted the NSDAP or one of its wings as the mass base they needed for their projects and advocated their participation in power at Hindenburg.

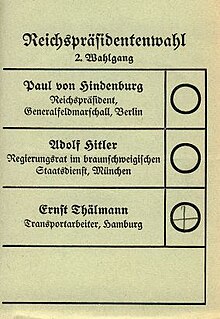

In order to be able to run against Hindenburg in the March / April 1932 presidential election, Hitler, who had been stateless since April 30, 1925 , had to become a citizen of a federal state and thus a German under Section 1 of the Reich and Citizenship Act (see Adolf Hitler's naturalization February 1932). As a convicted person for high treason, he sought the "employment in direct or indirect civil service", which was possible under Section 14 of the Reich and Citizenship Act, which was "for a foreigner as naturalization [...]" in order to circumvent the anticipated concerns of a federal state against his naturalization . After several unsuccessful attempts, the Minister of the Interior in the Free State of Braunschweig Dietrich Klagges (NSDAP) appointed him three days after the announcement of his candidacy for the Braunschweig government council . However, Hitler never started his intended service, but was immediately given leave for the election campaign and later applied for unlimited leave for his future "political struggles". He was only dismissed from the Braunschweig civil service as Chancellor on February 16, 1933.

In the second ballot on April 10, Hindenburg was re-elected with 53% of the vote, while Hitler received only 36.8% of the votes cast. On Brüning's advice, many SPD voters voted for Hindenburg as a “lesser evil” in order to prevent Hitler's victory and thus the end of Weimar democracy. However, the re-elected Hindenburg dismissed Brüning on May 29, appointed Franz von Papen as the new Chancellor and dissolved the Reichstag.

The NSDAP used all state and Reich elections planned for 1932 for constant agitation . Hitler hired the opera singer Paul Devrient as a voice trainer and campaign supervisor and from April to November 1932 had himself flown in to 148 large-scale rallies, which were attended by an average of 20,000 to 30,000 people. The Nazi propaganda staged him as a savior ("Hitler over Germany") standing above the social classes of a movement . He became better known among the population than any other candidate before him. Dozens of people died violently in provocative NSDAP marches during this election campaign. The " Altona Blood Sunday " (July 17), for example, offered von Papen's government the opportunity to overturn the state government of Prussia , which was incumbent in accordance with the constitution, by means of an emergency ordinance ( Preussenschlag , July 20).

In the Reichstag election of July 1932 , the NSDAP was the strongest party with 37.3 percent. Hitler claimed the Chancellery. At the second Reichstag session on September 12, Hindenburg dissolved the Reichstag as a result of tumult over its emergency ordinances. In the Reichstag election in November 1932 , the NSDAP was again the strongest party with 33.1 percent, despite a loss of votes; the KPD also gained seats, so that the democratic parties could no longer have a parliamentary majority. Thereupon von Papen resigned and suggested to Hindenburg that he be appointed dictator by emergency decree.

“National conservative forces in the economy, military and bureaucracy” strived for the “authoritarian (monarchist) restructuring of the state”, the “permanent elimination of the KPD, SPD and trade unions”, the “reduction of the tax and welfare state burdens on the economy”, the “rapid overcoming of the Versailles Treaty ”and the“ armament ”. They believed that they could only achieve their goals with the support of the National Socialist mass movement. For them unwanted parts of Hitler's program (dictatorship instead of monarchy, consideration of workers' interests), these elites wanted to weaken Hitler by “framing” Hitler and “taming” his policies. For this purpose, von Papen appeared to them to be a suitable ally, since he “still had the full confidence of Hindenburg and was the only one able to dispel his distrust of Hitler”. Most industrialists continued to reject Hitler's chancellorship. The long-held notion that Hitler came to power thanks to funding from big industry is now considered a " legend " or a " myth ".

Early on, Hitler subordinated criticism of capitalism in the NSDAP to anti-Semitism, according to which only the Jews were to blame for economic misery. Hitler's speech at the Düsseldorf Industrial Club in early 1932 praised the role played by the business elite and emphasized against the voters of the left-wing parties: The German people could not survive as long as they viewed half of their property as theft . After Hitler had established good relationships with business circles by the end of 1932 and had largely allayed their concerns about the Nazi economic program, large-scale industry supported the rise of the NSDAP in the Schacht office or in the economic policy department of the NSDAP , primarily through "business representatives from the second and third Member of the iron and steel industry ”and later Aryanization profiteers , but also bankers and large agrarians: They tried to reconcile a future Nazi economic policy“ with the prosperity of the private economy ”so that“ industry and trade can participate ”.

In order to avoid the risk of a civil war and a possible defeat of the Reichswehr against the paramilitary forces of the SA and KPD, Hindenburg appointed Kurt von Schleicher as Reich Chancellor on December 3rd. This had become Reichswehr Minister under von Papen and apparently took a more worker-friendly course. Schleicher tried to split the NSDAP with a cross-front strategy: Gregor Strasser was ready to accept Schleicher's proposal to participate in the government, to become Vice Chancellor and thus to bypass Hitler. This asserted his leadership role in the NSDAP and claim to the Chancellery in December 1932 amid tears and threats to kill himself. Hindenburg's conservative advisors had failed in their attempt to involve the NSDAP in the government without granting Hitler the chancellery.

The meeting between Papen and Hitler in the house of the banker Schröder on January 4, 1933 is considered to be the "hour of birth of the Third Reich", which initiated "an immediate causal sequence of events up to January 30": when Hitler von Papen became Vice Chancellor, the occupation of the classic ministries with German nationals and offered the right to be present at all lectures by the Chancellor to the Reich President, he obtained the latter's approval. Von Papen and Hugenberg also believed that they could “frame” and “tame” a Reich Chancellor Hitler in a government dominated by conservative ministers. Its alliance with Hitler isolated Schleicher's government, which the National Socialist-led Reichslandbund put under additional pressure in the protective tariff conflict between agriculture and the export industry.

In the state elections in Lippe in 1933 (January 15), the NSDAP became the strongest party with 39.5 percent of the vote (out of 100,000 eligible voters ) and thus saw its claim to leadership strengthened. When the abuse of Osthilfe threatened Hindenburg's reputation, his friend Elard von Oldenburg-Januschau campaigned personally for Hitler's chancellorship, from whose cabinet he expected the scandal to be covered up. In addition, on January 22nd, Hitler won Oskar von Hindenburg as a supporter with threats and offers. This removed the Reich President's last reservations about his appointment.

When General Werner von Blomberg was won over to Hitler's government with the promise to become the new Reichswehr Minister, Schleicher lost the solid support of the Reichswehr and was completely isolated and unable to act. When Hindenburg rejected his request for new elections, he resigned on January 28, 1933. Hitler, von Papen and Hugenberg had meanwhile agreed on a cabinet. This made Hitler's appointment as Reich Chancellor possible.

Rule before World War II (1933-1939)

Establishment of the dictatorship

On January 30, 1933, Hindenburg first unconstitutionally appointed Blomberg as the new Reichswehr Minister because the NSDAP had spread rumors of a coup in Berlin. Only then did he swear in Hitler and the rest of the cabinet and allow him the required dissolution of the Reichstag in order to enable new elections. So Hindenburg wanted to achieve the political unification of the right-wing parties in a coalition government dominated by German nationalists. Accordingly, almost all ministers in Hitler's cabinet belonged to the DNVP. Apart from Hitler, the only representatives of the NSDAP were Wilhelm Frick , who held a key department with the Reich Ministry of the Interior, and without the Göring division, who now controlled the police in the largest German state as the "Reich Commissioner for the Prussian Ministry of the Interior". This enabled the NSDAP to determine domestic politics in Germany.

As soon as he moved into the Old Reich Chancellery , Hitler is said to have said: “No power in the world will ever get me out of here alive.” Even before the new elections, the Hitler government restricted basic rights by decreeing the Reich President for the protection of the German people , until the Reichstag fire of February 27, as the alleged starting signal for a communist uprising, gave her the pretext for the Reich President's ordinance on the protection of the people and the state (Reichstag Fire Ordinance ) . The ordinance, written by Frick on Hitler's initiative and unanimously approved by the cabinet, abolished fundamental rights such as freedom of assembly , freedom of the press and the confidentiality of letters and made it possible to arrest political opponents. It established the state of emergency for the entire period of National Socialism until 1945. It is therefore considered to be the actual “constitutional document of the Third Reich”.

In the election campaign that followed, Hitler's regime had many opponents, especially communists, intimidated, arrested or murdered. Nevertheless, the NSDAP and DNVP missed the two-thirds majority necessary for constitutional amendments in the Reichstag elections on March 5 . Hitler ran for constituency 24 (Upper Bavaria-Swabia) and became a member of the Reichstag . On the day of Potsdam , the opening of the Reichstag on March 21, the NSDAP and Deutschnationale staged their unification under the leading figure of Hindenburg. On March 23, 1933, after the KPD mandates were canceled due to the Reichstag Fire Ordinance, the Reichstag passed the constitution- amending Enabling Act with the votes of the bourgeois parties . It allowed the regime to pass laws directly for an initial four years. The Reichstag thus renounced its role as legislator ( legislative branch ) , left it to the government ( executive branch ) and disempowered the Reich President. This allowed Hitler's dictatorship and the DC circuit of the state and society . On May 2nd, after the May celebrations of the previous day, the Nazi regime smashed the free trade unions and instead founded the German Labor Front on May 10th . On June 22nd, the SPD, whose MPs were the only ones who voted against the Enabling Act, was banned and the other parties were ordered to dissolve themselves by July 5th. On December 1, 1933, the NSDAP became the only state party with the law to ensure the unity of party and state . In this process, “pressure from 'below'” and Hitler's “personal initiative” worked together.