Carl von Ossietzky

Carl von Ossietzky (born October 3, 1889 in Hamburg , † May 4, 1938 in Berlin ) was a German journalist , writer and pacifist .

As editor of the magazine Die Weltbühne , Ossietzky was more often dragged before the judiciary because of articles that dealt with illegal conditions in the Weimar Republic and the rise of National Socialism. In the internationally sensational Weltbühne trial he was convicted of espionage in 1931 because his magazine had drawn attention to the illegal armament of the Reichswehr . Shortly after his release, the Nazis came to power . Ossietzky was illegally imprisoned on February 28, 1933. As one of the most prominent political prisoners, Ossietzky was among others in the Esterwegen concentration campspecial victim of National Socialist arbitrariness. He was frequently ill-treated and tortured. In 1936, Ossietzky received the Nobel Peace Prize in an international aid campaign . In the same year, seriously ill from the torture, he was transferred to a Berlin hospital under police surveillance. There he died under guard two years later.

Life

Early years and education

Carl von Ossietzky was born in Hamburg in 1889 as the child of Carl Ignatius von Ossietzky and Rosalie, née Pratzka. The father Carl Ignatius (1848-1891) came from a Catholic-Polish family. He was the son of a district official from Upper Silesia. After serving as a soldier, he moved to Hamburg. There he worked as a poorly paid stenographer in the law firm of the senator and later Hamburg mayor Max Predöhl . He also ran a dairy shop and catering business. The mother Rosalie came from a German-Polish family. The family lived in the Gängeviertel .

Carl was baptized on November 10, 1889 in the Catholic Little Michel and on March 23, 1904, he was confirmed as an Evangelical Lutheran in the main church of St. Michaelis . When the father died in Carl's third year, his sister took over the upbringing of Carl, the only child remained, while the mother continued to look after the restaurant. Senator Predöhl supported the family after the death of his father and found a free place for young Carl at the Rumbaumsche School , which was attended by children of wealthy families. Ten years after the death of her husband, Rosalie von Ossietzky married the sculptor and Social Democrat Gustav Walther, and they both took the boy in with them. Walther aroused Ossietzky's interest in politics. So they attended party events together, at which the SPD chairman August Bebel spoke, which left a lasting impression on Ossietzky.

Ossietzky was a bad student. After attending a private secondary school for eight years and attending a private evening school (Institut Dr. Goldmann), he tried twice, without success, to pass the state examination for the secondary school leaving certificate. In contrast to other subjects, Ossietzky's performance in mathematics and business arithmetic was poor. His interests were more focused on literature and history. So he stayed away from school from time to time at a young age in order to read literary classics such as Schiller , Goethe and Holderlin undisturbed . Since he was denied an academic career, he applied for a position at the Hamburg justice administration at the age of 17. It was only thanks to the intervention of his advocate Predöhl that he was even allowed to take the recruitment test. Finally, Ossietzky had moved up to first place on the waiting list for “auxiliary clerks to be employed” and entered the judiciary on October 1, 1907. In 1910 he was transferred to the land registry due to acceptable performance.

Ossietzky led a kind of double life during his time in the judiciary. During the day he spent the hours in the office, in the evening he attended as many cultural and political events as possible. He also wrote many poems on the side. One of his first literary attempts at that time was a romantic play that he wrote for a Hamburg actress with whom he was in love.

In 1908 he joined the German Peace Society . In the same year he joined the Democratic Association around Hellmut von Gerlach and Rudolf Breitscheid . At the time, Ossietzky was ideologically close to the monism of the popular zoologist and Darwinist Ernst Haeckel . With his strong belief in this world and progress , monism was attractive to a person like Ossietzky, who hoped for an improvement in general living conditions from science and technology and, as an atheist , wanted to reduce the influence of the church on upbringing and education.

Pacifist soldier

In 1911 Ossietzky sent his first contribution to the weekly newspaper Das frei Volk , the publication organ of the Democratic Association. A regular workforce developed from this initiative in the years that followed. Ossietzky was the first to write an editorial in a magazine. He also wrote regularly for the papers of the Deutscher Monistenbund .

In 1914 he made acquaintance with the judiciary in a way he was unfamiliar with: On the basis of the article “The Erfurt judgment” he was charged with “public insult” because he had strongly criticized the Prussian military justice system. The 200 Mark fine he was sentenced to was paid for by his wife Maud , whom he married on August 19, 1913. Ossietzky met Maud Lichfield-Woods, the daughter of a British colonial officer and great-granddaughter of an Indian princess, in Hamburg in January 1912. At that time she was active in the English women's rights movement. After the marriage, she supported her husband's plans to give up the judicial service in favor of a journalistic career. In January 1914, Ossietzky submitted his resignation.

At the beginning of the First World War , Carl von Ossietzky was initially patterned as unfit. The war-related changes in the media made it impossible for him to continue to earn his living as a journalist critical of the military and later even a pacifist journalist. Therefore, he returned to the judicial service in January 1915. In the summer of 1916 he was finally drafted and sent to the Western Front as an armored soldier .

By this time he had broken away from his initial enthusiasm for the war and gave pacifist lectures in Hamburg, where he was elected to the board of the local branch of the German Peace Society (DFG). In the course of the war he also attacked various leaders of the Monistenbund, such as Ernst Haeckel and Wilhelm Ostwald , who saw the war as an instrument for the worldwide implementation of the German culture they regarded as superior. In his 1917 manuscript Monism and Pacifism , Ossietzky resolutely opposed such an interpretation of the Darwinian concept of development and accused Haeckel and Ostwald of “ pan-Germanic fantasies at the expense of humanistic reason” (Suhr, p. 80 f.). After the end of the war, Ossietzky returned to Hamburg, where he once more resigned from the judiciary.

Journalist in Berlin

Building an existence as a journalist proved difficult, however. Ossietzky took a low-paid position as a lecturer in the pathfinder publishing house. He also published the zero number of the monistic magazine Die Laterne . Since he was elected first chairman of the Hamburg DFG section, he was often on the road to lectures. When in mid-1919 he finally had the opportunity to become secretary of the DFG in Berlin, the Ossietzky couple moved to the capital of the Reich. There in October 1919 he was one of the founding members of the Peace Association of War Participants (FdK), which he founded together with Kurt Tucholsky and other pacifists. Since Ossietzky was already advocating a more radical pacifism than DFG chairman Ludwig Quidde at that time and found little pleasure in purely organizational tasks, he quit his position as DFG secretary in June 1920 and returned to journalism full-time.

In 1919 his daughter Rosalinda was born.

From January 1920 to March 1922, under the pseudonym Thomas Murner, he wrote the column entitled Von der deutschen Republik in the Monist monthly magazine . From 1920 to 1924 he worked for the Berliner Volks-Zeitung , initially as a foreign policy employee and later as an editor. In addition, he was heavily involved in the "Never Again War" movement, which was founded under the leadership of the FdK. On every anniversary of the outbreak of war, August 1st, a “Never Again War Action Committee” organized large events in various German cities, especially in Berlin. For the movement, Ossietzky also published its own communication organ.

The pacifist and journalistic work, which included publications in numerous media, was apparently not enough for Ossietzky to anchor the ideas of democracy and republic more firmly in the German population. In March 1924 he therefore founded the Republican Party (RPD) together with the Volkszeitung editor Karl Vetter . Ossietzky formulated the party program, which was based on the ideals of the March Revolution of 1848 and the November Revolution of 1918. It provided for a strengthening of the state vis-à-vis the private sector for the common good and contained cautious demands for the socialization of industry. The RPD also advocated the creation of popular self-government institutions. The demand for a German " unified republic " to unite all people "German tongue" and culture was heard.

With the vague concept of a democratic state socialism , the party differed from both the SPD and the KPD. Ossietzky was not to give up this position until the end of the Weimar Republic , which kept him at a distance from the two major parties in the labor movement. Critics and even friends like Hellmut von Gerlach accused the party above all of merely contributing to the fragmentation of the democratic and republican forces. Since the party received only 0.17 percent of the vote and no mandate in the Reichstag election of May 1924 , it was dissolved soon afterwards.

After his unsuccessful foray into party politics, Ossietzky did not return to the Volkszeitung , but instead became an employee and soon afterwards editor of Stefan Großmann's and Leopold Schwarzschild's magazine Das Tage-Buch . The collaboration with the renowned journalists did not last long, as, in Ossietzky's opinion, both of them did not attack the military sharply enough and preferred to write themselves on important topics. Therefore, as early as February 1925, he was determined to switch from the Tages-Buch to the Weltbühne . A criminal complaint brought against him induced him to postpone his dismissal. In the winter of 1925/1926 he temporarily stayed at the Monday morning in Berlin before he dared to take the decisive step in his career.

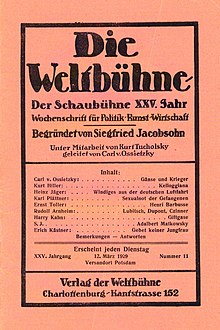

Editor of the Weltbühne

At Tucholsky's suggestion, Siegfried Jacobsohn , editor of the Berlin weekly Die Weltbühne , sought Ossietzky's collaboration from the summer of 1924. It was not until April 1926 that a political editorial of his appeared in the paper for the first time. After Jacobsohn's death, the widow Edith Jacobsohn appointed - after a brief interregnum by Kurt Tucholsky - Ossietzky as publisher and editor-in-chief of Weltbühne .

The magazine was printed in Potsdam's oldest print shop at that time , the Edmund Stein print shop, which printed for the August Stein publishing house, the Royal Government of Potsdam, the Royal High Presidium and the Ministry of Finance until 1918, and after the First World War shifted her field of activity to magazines. Since it was founded in 1887, the Stein printing company has been located in the inner city of Potsdam, in the backyard of Hegelallee 53, at that time "Jäger-Kommunikation 9". Ossietzky, Tucholsky and their circle edited and wrote their famous leading articles for the Weltbühne in the nearby “Café Rabien” (today “Café Heider”) in front of the Nauener Tor in the Dutch Quarter .

Under the direction of Ossietzky, the world stage retained its importance as an undogmatic forum for the radical democratic, bourgeois left. The fact that Ossietzky gained a great reputation in this function is also shown by the fact that after the Berlin Blutmai in May 1929 he took over the chairmanship of the committee that was supposed to clarify the background to the violent police operation. Nevertheless, for the communists, Ossietzky was a "despised and fought symbol" of the bourgeois opposition. The Social Democrats attacked him and ridiculed him as an "idealist". The liberals saw him as a “republic destroyer”.

Ossietzky finally came into the focus of the international public through indictment against him in the so-called Weltbühne trial . The article Windy from the Luffahrt of Walter Kreiser from 1929, which had led to the indictment, had the forbidden in international treaties, secret preparation of the air forces of the Reichswehr revealed. At the end of 1931, Ossietzky and the aircraft expert were finally sentenced to 18 months in prison for betraying military secrets. In 2017 it was discussed whether Ossietzky was a whistleblower . Unlike Kreiser, Ossietzky strictly refused to evade prison stay by fleeing abroad. Instead, after his pardon was denied and his imprisonment was imminent, he said:

"There is one thing I do not want to be mistaken about, and I emphasize this for all friends and opponents and especially for those who have to look after my legal and physical well-being for the next eighteen months: - I do not go to jail for reasons of loyalty, but because I am the most uncomfortable as a prisoner. I do not bow to the majesty of the Reichsgericht, wrapped in red velvet, but remain as an inmate of a Prussian penal institution a lively demonstration against a highest instance judgment, which appears politically tendentious in the matter and which is a lot wrong as legal work.

The episode passed down from Weltbühne employee Walter Mehring that the later Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher personally came to the editorial office of the magazine to persuade Ossietzky to leave for Switzerland . Ossietzky commented on this experiment with the words: "Now the gentlemen who made me the prison soup should also spoon it out themselves."

Ossietzky caused an outcry in the democratic and social democratic press when he recommended voting for the communist candidate Ernst Thälmann before the presidential election in March / April 1932 . His recommendation is all the more surprising when one takes into account that in January 1932 Ossietzky had accused the KPD of having " reacted in the most impossible way " with the listing of Thälmann and of having prevented a joint leftist candidate. The suggestion had previously come from circles around the world stage that Heinrich Mann should be nominated as a candidate against Hitler and Hindenburg, but the KPD had stuck to its chairman. In his recommendation before the first ballot, Ossietzky also admitted that the vote for Thälmann " does not mean a vote of confidence in the Communist Party ". In his eyes, with incumbent Paul von Hindenburg, it was not a program that won, but one

“A historical name which, from a realpolitical point of view, only represents a Zéro, before which a concrete value must first be placed. Whoever is allowed to bet this number will be the real winner in the end. "

When Hindenburg rejected the “ political zero ”, Ossietzky did not take into account the fact that Hindenburg had to decide at the same time on his appeal for clemency in the Weltbühne trial. Since the application was rejected at the end of March 1932, Ossietzky began his sentence on May 10, 1932 in the Berlin-Tegel prison. Numerous friends and political companions insisted on accompanying Ossietzky to the prison gate. Fears that Ossietzky could be harmed by retaliatory harassment of the state power while in custody did not materialize. Alfred Polgar gave credit to the caring attitude of the prison director Felix Brucks towards his prisoners, including the hope he had expressed when Ossietzsky's commencement of prison on the Weltbühne that he “would not suffer more harm than the fact that he was a prisoner is “confirmed.

Ossietzky was also sued for the famous Tucholsky sentence “ Soldiers are murderers ”. In July 1932, however, a court did not evaluate this sentence as a disparagement of the Reichswehr and acquitted those who had already been arrested from the new indictment. Due to a Christmas amnesty for political prisoners, Ossietzky was released early on December 22, 1932 after 227 days in prison.

Torture and imprisonment in a concentration camp

As a committed pacifist and democrat, he was arrested again on February 28, 1933 at the instigation of the National Socialists and interned in the Berlin-Spandau prison. Until recently, Ossietzky had hoped that a united front made up of social democrats and communists could oppose the threatening Nazi dictatorship . He believed that the NSDAP would break due to its internal contradictions after taking over government. Private reasons also prevented him from escaping the expected arrest by fleeing abroad (see below ).

During the book burnings by students in Berlin and numerous other German cities on May 10, 1933, there was agitation against Ossietzky and Tucholsky: “Against impudence and presumption, for respect and awe of the immortal German national spirit! Devour, flame, also the writings of Tucholsky and Ossietzky! ”.

On April 6, 1933, Ossietzky was deported from Spandau to the newly established Sonnenburg concentration camp near Küstrin . Like the other inmates, he was severely ill-treated there. The conditions in the camp, which was initially run by the SA , ultimately led to the SS under Heinrich Himmler professionalizing the camp system in the spring of 1934. Ossietzky was transferred with other known prisoners from Sonnenburg to the Esterwegen concentration camp in northern Emsland . There the prisoners were used under unbearable conditions to drain the Emsland high moors . At the end of 1934, the completely emaciated Ossietzky was transferred to the infirmary. According to a report from a fellow inmate, Ossietzky was supposed to be murdered by injections in the sick camp. Whether Ossietzky, as the prisoner claims, was actually injected with tuberculosis bacilli has not been proven beyond doubt. In autumn 1935, the Swiss diplomat Carl Jacob Burckhardt visited the Esterwegen concentration camp as a member of the International Committee of the Red Cross . He also managed to meet Ossietzky, whom he then described as a "trembling, death-pale something, a being that seemed to be numb, one eye swollen, its teeth apparently broken in" . Ossietzky said to Burckhardt:

“Thank you, tell your friends that I'm finished, it will soon be over, soon over, that's good. […] Thank you, I received a message once that my wife was here once; I wanted peace. "

Carl Jacob Burckhardt's statements are now in part doubted; some doubt the authenticity of the quotation and the descriptions in his book about Ossietzky.

Due to the public appeals described in the following paragraph, Ossietzky was finally transferred to the Berlin State Police Hospital in May 1936, where severe open lung tuberculosis in an advanced state was diagnosed.

Nobel Prize Campaign

As early as 1934, Ossietzky's friends Berthold Jacob in Strasbourg and Kurt Grossmann in Prague on behalf of the German League for Human Rights (of which he was a member of the board from 1926 to 1927) submitted the first official application to honor Ossietzky with the Nobel Peace Prize . But this attempt was doomed to failure because the application deadline for 1934 had already expired and the Human Rights League was not entitled to make proposals. Since Jacob had informed the press about the proposal, attention was directed from that point on to the concentration camp inmate Ossietzky.

Other friends of Ossietzky, such as Hellmut von Gerlach and the former employees Hilde Walter , Milly Zirker and Hedwig Hünecke, tried to support the prisoner in a more secretive way. They promoted the renewed campaign in 1935 by soliciting numerous foreign celebrities for the support of the proposal. They feared that an overly aggressive campaign by the German exiles could more likely harm the prisoner. Therefore Kurt Tucholsky also held back with public statements on this question, although he tried to assert his influence through personal letters. Despite the mobilization of the international public, the Nobel Prize Committee in 1935 shied away from awarding the prize to Ossietzky. Because the National Socialist government had exerted strong foreign policy pressure on the Norwegian government. As a result, the award for 1935 was not awarded to any other candidate.

The campaign continued unabated in 1936, which ultimately led to Ossietzky being released from the concentration camp shortly before the 1936 Olympic Games and being transferred to the state hospital in Berlin. He was officially released from prison on November 7, 1936 and initially moved into a room in the Westend hospital, under constant surveillance by the Gestapo . Despite these concessions, the international campaign organized in Norway by the German émigré Willy Brandt had meanwhile achieved its goal. On November 23, 1936, Carl von Ossietzky was retrospectively awarded the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize.

The then Prussian Prime Minister Hermann Göring personally urged Ossietzky not to accept the award. But in vain, Ossietzky's answer was:

“After much deliberation, I came to the decision to accept the Nobel Peace Prize that had been awarded to me. I am unable to share the view expressed to me by the representative of the Secret State Police that I am thereby excluding myself from the German national community. The Nobel Prize for Peace is not a sign of internal political struggle, but of understanding between peoples. "

The Gestapo refused to allow Ossietzky to travel to Oslo to receive the award. Adolf Hitler then decreed that no more Reich Germans would be allowed to accept a Nobel Prize in the future. Instead, the German National Prize for Art and Science was awarded from 1937 .

A few days after receiving the Nobel Prize, Ossietzky was transferred to the Nordend Hospital ( Berlin-Niederschönhausen ), where he was able to stay in a special TBC department under police surveillance. Maud von Ossietzky played a tragic role in the attempt to sensibly invest the prize money associated with being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize . She fell for the lawyer Kurt Wannow , who assured her that he would manage the prize money of almost 100,000 Reichsmarks. But Wannow embezzled the money, so that it finally came to the process.

death

On May 4, 1938, Ossietzky died under police surveillance in the Nordend hospital as a result of severe abuse by the SS and the tuberculosis he had contracted in the concentration camps. He left behind his wife Maud and his daughter Rosalinda , who were able to emigrate to Sweden via England.

Ossietzky's grave and that of his wife Maud are located in the Pankow IV cemetery on Herthaplatz in Berlin-Niederschönhausen. It is an honor grave of the city of Berlin .

Individual aspects and reception

Outstanding stylist

Ossietzky was recognized by his contemporaries as a great stylist and compared on various occasions with Heinrich Heine , Maximilian Harden or even Voltaire .

“His best portrait is his style. His clear and supple German, the securely seated word, the short and loosely swaying rhythm of his sentences, the secret irony of his allusions, often humorously glossy and the relentlessly sitting foil pile of his attack [...] "

It should also be emphasized that Ossietzky was the only employee of the Weltbühne who Siegfried Jacobsohn allowed to send his texts to the printer without looking. Not even Tucholsky received this honor.

Behind the offensive and aggressive style, however, hid a very reserved and shy person, as his friends and co-workers consistently reported. After meeting him for the first time, Jacobsohn described Ossietzky as one of the “greatest circumstances commissioners I have ever met”, but his language was “not made of paper”. Tucholsky characterized him after his arrest by the National Socialists:

“This excellent stylist, this man who is unsurpassed in his moral courage, has a strangely lethargic manner which I did not understand and which probably alienates him from many people who admire him. It's a shame about him. Because this sacrifice is completely pointless. "

His colleague Rudolf Arnheim , on the other hand, described Ossietzky in his quiet and modest manner as the only real hero he had ever known. He described Ossietzky's demeanor as follows:

"Restrained and silent, the cigarette in his gently trembling hand, his eyes downcast, he looked like a subtle aristocrat, not easily accessible to visitors, but to friends and employees a warm-hearted comrade, a selfless helper [...]"

Controversial editor

Opinions were divided about Ossietzky's achievements as an editor during his lifetime. The collaboration between Tucholsky and Ossietzky in particular was not without tension, as Ossietzky was a completely different editor from Tucholsky's mentor Jacobsohn. From Tucholsky's letters to his wife Mary Gerold it emerges that in 1927 and 1928 he was anything but satisfied with the way his successor "Oss" worked. Typical passages of letters read: "Oss does not answer at all - does not respond to anything - and certainly not out of meanness, but out of laziness" (August 14, 1927); “Oss very far away. I have the vivid impression that I am disturbing. He doesn't like me and I don't like him anymore. Treats me with too little respect for the crucial nuance. Got Upside Down ”(January 20, 1928); “Oss is a hopeless case - he doesn't even know how boring he makes everything. He is lazy and incompetent. ”(September 25, 1929) It was only in the years to come that the two journalists should come closer both personally and personally, so that in May 1932 Tucholsky finally admitted that Ossietzky had given the paper a“ tremendous boost ”.

In the opinion of Weltbühne employee Kurt Hiller , Ossietzky completely lacked the "editorial passion", so that the paper edited itself under his direction, as it were. Hiller is said, however, that he himself had ambitions to be the editor of the world stage and therefore always viewed Ossietzky as an annoying adversary whom he could not bring to his own political line.

Ossietzky's close associates, mostly young journalists like Arnheim and Walther Karsch , however, admired his camaraderie. In Arnheim's view, Ossietzky did not edit the contributions of his established employees out of convenience, but rather out of respect for freedom of expression.

His family also felt that Ossietzky must have been anything but lazy. Daughter Rosalinde, who had meanwhile been given to a children's home in Lehnitz near Berlin, complained in retrospect: "The paper took my father from me and made my mother sick," which meant Maud von Ossietzky's alcohol addiction.

Involuntary Martyr?

So far, research has not been able to clarify beyond any doubt whether Ossietzky had consciously stayed in Germany after the National Socialists came to power , although he had to reckon with being arrested, or whether he was arrested because the National Socialists had planned or at least intended to escape Ossietzky with his arrest had come first. Ossietzky himself does not have any clear statements on this question. Some contradicting statements have been handed down from close friends. In conversations with journalists such as Béla Balázs and Franz Leschnitzer , Ossietzky is said to have been indomitable and refused to flee because of his credibility. His colleague Rudolf Arnheim, on the other hand, stated that Ossietzky was basically ready to flee and only wanted to wait for the result of the Reichstag elections of March 5, 1933 . He is also said not to have prevented the secretary of the Weltbühne from ordering an international ticket. Ossietzky knew from warnings from officials he was friends with, such as Robert Kempner , that the National Socialists had prepared arrest lists containing his name.

One of the main reasons for Ossietzky's hesitant attitude was probably his wife Maud's alcoholism. Since the family had no financial reserves and had even gone into debt at the beginning of 1933 in order to be able to set up their own apartment for the first time, they were urgently dependent on Ossietzky's income. From abroad it would probably have been impossible for him to provide for his family. His behavior on February 27, 1933, the evening of the Reichstag fire, was also decisive for the arrest . That evening Ossietzky stayed with some friends like Hellmut von Gerlach , Hilde Walter and Milly Zirker in the apartment of the journalist and architect Gusti Hecht . Hecht is in various letters Walters as the referred friend Ossietzkys; The two therefore had a relationship with each other , if you add further information .

Since the round had heard of the Reichstag fire, Ossietzky was urgently advised against returning to his apartment that night. However, he ignored the advice and did not stay, as he had done before, in his girlfriend's apartment. Instead, he relied on the fact that there were no names on the door of his apartment and that the police would not find him because of it. Concern for his wife Maud may also have played a role in this decision. He was arrested early in the morning on February 28th. On the other hand, other employees of the Weltbühne , such as Hellmut von Gerlach, managed to flee abroad.

Ossietzky was soon stylized by exiles as a martyr who voluntarily placed himself in the hands of the National Socialists:

“Georg Bernhard and Thomas Mann called Ossietzky the 'martyr of the peace idea', Heinrich Mann repeatedly spoke of the 'sufferer', Arnold Zweig took up the martyr motif in an article for an advertising pamphlet in favor of Ossietzky's Nobel Prize candidacy, and Kurt Tucholsky spoke critically of the 'martyr of no effect'. "

In this context, the statement he had made in 1932 before entering prison was often used:

“In the long run, the exclusively political publicist cannot do without the connection with the whole, against which he is fighting, for which he is fighting, without falling into exaltations and lopsidedness. If you want to fight the contaminated spirit of a country, you have to share its common fate. "

Attitude to the republic

After the end of the Second World War, representatives of the radical left were often accused of having contributed to their downfall with their irreconcilable attacks on representatives of the Weimar Republic. These allegations were also made by Tucholsky and Ossietzky as editors of the Weltbühne . Der Spiegel publisher Rudolf Augstein criticized the newspaper's exaggerated demands on politicians:

“In their intellectual and formal aesthetic area, the protagonists of the 'world stage' were personalities, undoubtedly. But that seduced them to an exaggerated search for personality in the political arena, where the facts are known not to be made of ethereal material. A ruling Social Democrat always had the advantage of failing as a personality. He was then called, for example, 'Fountain pen owner Hermann Müller '. "

This attack was aimed at Ossietzky, who had criticized the social democratic financial politician Rudolf Hilferding , for example , that he lacked “the waving helmet plume” and “that which inspires”. Augstein therefore counted the Weltbühne among the grave diggers of the Weimar Republic, albeit with the restriction that it was only the grave diggers who “bring a corpse to death in the rarest of cases. Rather, they put the corpse, which is already dead, underground. "

In the early 1980s, the historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler struck out another violent blow against Ossietzky . In an essay he compared the achievements of Leopold Schwarzschild 's book of days with Ossietzky's Weltbühne and came to the conclusion:

“Every democracy must also be able to tolerate radical journalistic criticism. But the ethics of responsibility of democratic journalists must not allow them to cross the line to state hostility in principle. In his own way, Carl v. With the Weltbühne, however, Ossietzky contributed to weakening the deeply battered republic even further, and even actively discredited it through his criticism from the left, without giving any pardon. From the left world stage went, v. Ossietzky also believe that they will always fight for the republic, ultimately a destructive effect from [...] "

The fact that Ossietzky had hoped towards the end of the Weimar Republic that a kind of united front made up of social democrats and communists could block the way into the Third Reich was described by Wehler as “the feeble feeling of popular front romanticism” and explained this with “a serious loss of reality in the strict Freudian sense”.

It is also often noted that Ossietzky underestimated the dangerousness of National Socialism. Shortly before the election victory of the Nazis on September 14, 1930, he analyzed, for example, in a communist magazine:

“The National Socialist movement has a noisy present, but no future at all. It lives from the excitement of suddenly proletarian classes, to which political and economic forces they owe the fall from bourgeois security into a social pariatum . National Socialism has not yet proven that it is able to capture the old organized workforce and their young generation. [...] This movement has no idea and no principle and therefore it will not be able to live. "

Likewise, Ossietzky seems to have underestimated the person of Adolf Hitler as an assertive politician. In this context, a text from February 1931 is often used as evidence, in which it says:

“But this German Duce is a cowardly, effeminate pajama existence, a petty bourgeois rebel who quickly grew fat, who lets himself be well and only very slowly understands when fate and his laurels are put in acidic vinegar. This drummer only hits the calfskin in the stage. "

This assessment was probably based on the conviction that Hitler would not be able to legally take power with his party. Instead, after the election victory of September 14, 1930 , he should have seized the opportunity and seized power with his intoxicated supporters. Ossietzky doubted that the National Socialist movement, especially the SA, could remain in the opposition for more years. Nevertheless, he warned urgently against the "elephant kick of fascism" under which the country trembled in his opinion as early as 1932. Ossietzky wrote about the dismissal of Franz Höllering , who, as editor-in-chief of the BZ , had reported critically on Hitler's air fleet at noon :

"[...] nobody who is not professionally connected to the press can judge the scope of the Höllering case. […] Every editor of a still republican bourgeois newspaper will ask himself whether he will still be able to dare to bring news in the future that is unpleasant for Hitler and which may even cause high military officials to frown. [...] These are the unbelievably far-reaching consequences of the Höllering case, and therefore the behavior of the Ullstein house is more than an error of derouted business people. It is the most scandalous surrender to National Socialism that has ever been recorded. It is a crime against German press freedom in the midst of its worst crisis. "

When Kurt von Schleicher announced his resignation as Chancellor on January 28, 1933, Ossietzky reacted with astonishing calmness, but energetically demanded the return to a government legitimized by parliament:

“Nice consumption of rescuers. Another one gone. If the authoritarian regime continues to operate like this, it will soon be: every German once Reich Chancellor! Parents with large families, here is another chance! [...] If the path to the constitution is not immediately and unconditionally taken up again - and this includes the resignation of the Reich President - then the extra-parliamentary mode of government will be answered from below with extra-parliamentary defense methods. Because there is also an emergency right of the people against adventurous and experimental authorities. "

This sarcasm was due to the fact that Ossietzky - much like his colleague on the world stage, Kurt Tucholsky - saw little difference between the presidential regime and the expected participation of the National Socialists in government. Like many of his contemporaries, he had obviously not foreseen how quickly their unbridled brutality would set in. On February 14, 1933, he stated in the Weltbühne that it was above all Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen who until further notice should be seen as the head of the government . However, after his conviction in the Weltbühne trial , Ossietzky had already stated:

“Once the Third Reich is governed according to the Boxheim platform , then traitors like Kreiser and I will be fooled without a fuss. We have not yet entered the SA paradise, we still preserve the decorum of the legal process. [...]

We are at a fateful turning point. In the foreseeable future, open fascism can take control. It makes no difference whether he clears his way with legal means, so to speak, or with those that emerged from the hangman's fantasy of a Hessian court assistant. The most likely combination of both methods is likely: a government that turns a blind eye while the street remains at the mercy of the hooligan and cutthroat army of the SA commanders who bloodily suppress any opposition as a 'commune'. There is still the possibility of combining all anti-fascist forces. Yet! Republicans, socialists and communists, organized and dispersed in the big parties - for a long time you will not have the chance to make your decisions freely and not in front of the tip of the bayonets! "

Retrial

In the 1980s, German lawyers, including Heinrich Hannover , tried to get the world stage process to resume . This was intended to revise the 1931 judgment. Rosalinde von Ossietzky-Palm, the only child of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Carl von Ossietzky, initiated the proceedings on March 1, 1990 at the Berlin Court of Appeal . As new evidence, the reports of two experts were presented, which were supposed to show that the French army had been informed of the illegal activities of the Reichswehr before the text was published. In addition, some of the “secrets” complained of were not factual. The Court of Appeal declared a reopening of the proceedings as inadmissible. The new reports are not sufficient as facts or evidence to acquit von Ossietzky under the law of the time.

The 3rd Criminal Senate of the Federal Court of Justice then rejected a complaint against the decision of the Court of Appeal:

“According to the rulings of the Reichsgericht, the illegality of the secret events did not exclude the secrecy. In the opinion of the Reichsgericht, every citizen owes his fatherland a duty of loyalty, stating that the endeavor to comply with the existing laws could only be realized by making use of the national organs appointed for this purpose and never by reporting to foreign governments. "

With this decision, the Federal Court of Justice in 1992 involuntarily represented the legal opinion expressed by Hans Filbinger in his own case in 1978: "What was right then cannot be wrong today!"

Awards and honors

- The German International League for Human Rights (Berlin) has awarded the Carl von Ossietzky Medal since 1962 .

- Another Carl von Ossietzky medal was awarded by the Peace Council of the GDR since 1963 .

- In 1983 the Hamburg State Library was renamed the State and University Library Hamburg Carl von Ossietzky .

- The city of Oldenburg has awarded the Carl von Ossietzky Prize for Contemporary History and Politics every two years since 1984 .

- The Carl von Ossietzky monument was unveiled in Berlin in 1989.

- In 1991 the University of Oldenburg - after many years of opposition from the Lower Saxony state government in Hanover - named itself Carl von Ossietzky University Oldenburg . Ossietzky's daughter Rosalinde von Ossietzky-Palm was an honorary citizen of the university until her death in 2000 . The university also manages the estate of Carl and Maud von Ossietzky.

- In 1996, a bronze monument created by Manfred Sihle-Wissel was erected in the ramparts of the city of Oldenburg .

- Honorary grave of the city of Berlin in the cemetery Pankow IV - Herthaplatz, 13156 Berlin-Niederschönhausen .

- In Germany some schools are named after Carl von Ossietzky .

- There are several Carl-von-Ossietzky-Strasse in Germany, including in Chemnitz , Dortmund , Görlitz , Halle (Saale) , Leverkusen , Lüneburg , Marburg , Oldenburg , Potsdam , Wedel , Weimar and Wiesbaden .

- The magazine Ossietzky was named after Carl von Ossietzky.

- His relief portrait and the plaster model of the artist Klaus Kütemeier in the Carl-von-Ossietzky-Gymnasium in Hamburg-Poppenbüttel can be found in the hallway of the Hamburg City Hall .

- The Carl-von-Ossietzky-Park is located in the Berlin district of Moabit

Fonts

- All writings. Edited by Werner Boldt et al. With the participation of Rosalinda von Ossietzky-Palm. 8 volumes. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1994, ISBN 3-498-05019-2 .

- Fonts. 2 volumes. Construction, Berlin 1966.

- Accountability: Journalism from the years 1913–1933. Edited by Bruno Frei . Construction, Berlin 1970.

- Reader: holding up a mirror to time. Edited by the Carl von Ossietzky Research Center at the University of Oldenburg. Rowohlt, Reinbek 1989, ISBN 3-498-05015-X .

Letters:

- Dietger Pforte (Ed.): Colored signal signs that can be seen from afar. The correspondence between Carl von Ossietzky and Kurt Tucholsky from 1932. Akademie der Künste, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-88331-942-2 .

literature

Biographies

- Werner Boldt: Carl von Ossietzky (1889-1938). Donat, Bremen 2020, ISBN 978-3-943425-87-1 .

- Werner Boldt: Carl von Ossietzky: champions of democracy. Ossietzky, Hannover 2013, ISBN 978-3-944545-00-4 .

- Bruno Frei : Carl von Ossietzky. A political biography. Berlin 1978, ISBN 3-921810-15-9 .

- Dirk Grathoff: Ossietzky, Carl von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , p. 610 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Gerhard Kraiker and Elke Suhr: Carl von Ossietzky . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1994, ISBN 978-3-499-50514-0 (Rowohlt's monographs).

- Richard von Soldenhoff (ed.): Carl von Ossietzky 1889–1938. A picture of life. (Pictorial biography). Weinheim 1988, ISBN 3-88679-173-4 .

- Wilhelm von Sternburg : “It's an eerie atmosphere in Germany”: Carl von Ossietzky and his time. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-351-02451-7 .

- Elke Suhr: Carl von Ossietzky. A biography. Kiepenheuer and Witsch, Cologne 1988, ISBN 3-462-01885-X .

- Entry by Carl von Ossietzky. In Werner Treß Hrsg: Burned books 1933. With fire against the freedom of the spirit. Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 2009, pp. 318–329. (Contains a short biography up to p. 319 and up to p. 329 the reprint of the Ossietzky article: Antisemiten. , Die Weltbühne XXVIII Jg, 2nd Hj., No. 29 of July 19, 1929.)

Others

- Stefan Berkholz (Ed.): Carl von Ossietzky. 227 days in prison. Letters, texts, documents. Darmstadt 1988.

- Kurt Buck: Carl von Ossietzky in the concentration camp. In: DIZ news. Action committee for a documentation and information center Emslandlager eV, Papenburg 2009, No. 29, pp. 21–27: Ill.

- Julian Dörr, Verena Diersch: To justify whistleblowing. An ethical and legitimacy-theoretical perspective of the whistleblower cases Carl von Ossietzky and Edward Snowden . In: Zeitschrift für Politik, Volume 64, Issue 4, pp. 468–492, ISSN 0044-3360.

- K. Fiedor: Carl von Ossietzky and the peace movement. Wroclaw 1985.

- Ralph Giordano : Democrat without party doctrine and ideological dogma . Speech on April 28, 1989 in Wiesbaden at the Oberstufengymnasium West on the occasion of the change of name to Carl-von-Ossietzky-Schule. In: I'm nailed to this land. Speeches and essays about the German past and present. Knaur-TB 80024, Droemer Knaur, Munich 1994, ISBN 3-426-80024-1 , pp. 85-98.

- Friedhelm Greis, Stefanie Oswalt (Ed.): Make Germany out of Teutschland. A political reader on the “world stage”. Lukas, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-86732-026-9 .

- Alfred Kantorowicz : The outlaws of the republic. in: portraits. German fates. Chronos, Berlin, 1947, pp. 5-24.

- Gerhard Kraiker, Dirk Grathoff (ed.): Carl von Ossietzky and the political culture of the Weimar Republic. 100th birthday symposium. Series of publications from the Fritz Küster Archive. Oldenburg 1991, book as PDF

- Ursula Madrasch-Groschopp: The world stage. Portrait of a magazine. Buchverlag Der Morgen, Berlin 1983. (Reprint: Bechtermünz Verlag im Weltbild Verlag, Augsburg 1999, ISBN 3-7610-8269-X )

- Maud von Ossietzky: Maud von Ossietzky tells: A picture of life. Berlin 1966.

- Helmut Reinhardt (Ed.): Thinking about Ossietzky. Articles and graphics. Verlag der Weltbühne von Ossietzky, Berlin 1989, ISBN 3-86020-011-9 .

- Christoph Schottes: The Nobel Peace Prize campaign for Carl von Ossietzky in Sweden. Oldenburg 1997, ISBN 3-8142-0587-1 Book as PDF

- Elke Suhr: Two paths, one goal - Tucholsky, Ossietzky and Die Weltbühne. Weisman, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-88897-026-1 .

- Frithjof Trapp, Knut Bergmann, Bettina Herre: Carl von Ossietzky and political exile. The work of the “Friends of Carl von Ossietzky” in the years 1933–1936. Hamburg 1988.

- Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Leopold Schwarzschild versus Carl v. Ossietzky. Political reason for the defense of the republic against ultra-left “criticism of the system” and illusions of the popular front. In: Ders .: Prussia is chic again ... Politics and polemics in twenty essays. Frankfurt a. M. 1983, pp. 77-83.

Movies

- Carl von Ossietzky , German TV radio , 1963, director: Richard Groschopp , with Hans-Peter Minetti as Ossietzky.

- The trial of Carl von O. , television play NDR 1964, directed by John Olden , with Rolf Henniger as Ossietzky.

Documentation

Radio reports and podcast

- Carl von Ossietzky publicist, pacifist, republican, democrat . A podcast contribution from the radio station Bayern 2 from the radioWissen series : from November 30, 2012 on the homepage of the station Bayern2

Web links

- Literature by and about Carl von Ossietzky in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Carl von Ossietzky in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Works by Carl von Ossietzky in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Manfred Wichmann: Carl von Ossietzky. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG )

- Short biography of the German Resistance Memorial Center

- Biography at Shoa.de

- Short biography at the Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg

- Information from the Nobel Foundation on the award ceremony for Carl von Ossietzky in 1935

- Joachim Käppner : Against half the truth. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , May 21, 2003 - Ossietzky as a journalistic role model

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilhelm von Sternburg : "There is an eerie atmosphere in Germany": Carl von Ossietzky and his time. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-351-02451-7 , pp. 203f.

- ^ A b State capital Potsdam: "Between Brandenburger and Nauener Tor" www.potsdam.de, accessed on January 12, 2015.

- ↑ Potsdamer Latest News (PNN): “It goes also Krüger” www.pnn.de, accessed on January 12, 2015.

- ↑ Potsdam Edict of Tolerance: "Burned books, forbidden authors - Carl von Ossietzky" www. potsdamer-toleranzedikt.de, brochure “Burned books, forbidden authors” , p. 30, accessed on January 12, 2015.

- ^ Wilhelm von Sternburg : "There is an eerie atmosphere in Germany": Carl von Ossietzky and his time. Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-351-02451-7 , p. 207.

- ↑ Julian Dörr, Verena Diersch: On the justification of whistleblowing: A legal ethical and legitimacy theoretical perspective of the whistleblower cases Carl von Ossietzky and Edward Snowden . In: Journal of Politics . tape 64 , no. 4 , December 5, 2017, ISSN 0044-3360 , p. 468–492 , doi : 10.5771 / 0044-3360-2017-4-468 ( nomos-elibrary.de [accessed on January 22, 2018]).

- ↑ Later, his daughter Rosalinda von Ossietzky-Palm campaigned for the convictions for treason against him during the Weimar Republic to be overturned. However, the Federal Court of Justice ruled in 1992 that there was no legal basis for reassessing the 1931 ruling. An acquittal was not possible under the law at the time.

- ^ Carl von Ossietzky: 227 days in prison: letters, documents, texts. 1988, p. 94f.

- ^ Hermann Vinke: Carl von Ossietzky. Hamburg 1978, p. 138f.

- ^ Carl Jacob Burckhardt: My Danziger Mission: 1927 to 1939. Munich 1960, p. 60f.

- ↑ Grandiose adaptation: Der Spiegel 39/1991

- ^ Carl von Ossietzky - Biography. Nobelprize.org, accessed February 20, 2014 .

- ^ Carl von Ossietzky. In Werner Treß Hrsg: Burned books 1933. With fire against the freedom of the spirit. Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 2009, p. 329.

- ↑ Ursula Madrasch-Groschopp: The world stage. Portrait of a magazine. Berlin 1983, p. 212.

- ↑ Ursula Madrasch-Groschopp: The world stage. Portrait of a magazine. Berlin 1983, p. 213.

- ↑ Christoph Schottes: The Nobel Peace Prize campaign for Carl von Ossietzky in Sweden. Oldenburg 1997, p. 54.

- ^ A republic and its magazine . In: Der Spiegel . No. 42 , 1978, pp. 239-249 ( online - here p. 249).

- ↑ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: Leopold Schwarzschild contra Carl v. Ossietzky. Political reason for the defense of the republic against ultra-left “criticism of the system” and illusions of the popular front. In: Ders .: Prussia is chic again ... Politics and polemics in twenty essays. Frankfurt a. M. 1983, pp. 77-83.

- ^ Carl von Ossietzky: National Socialism or Communism. In: The Red Structure , ed. v. Willi Munzenberg , September 1930.

- ↑ Heinrich Hannover: The Republic in front of the court ( Memento of the original from November 17, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. contents

- ↑ Ivo Heiliger : Windy things from German jurisprudence. The Ossietzky decision of the Federal Court of Justice. (PDF; 496 kB)

- ^ Filbinger affair: Was Rechtens Was ... , In: Der Spiegel, No. 20, 1978, pp. 23-27.

- ↑ Carl von Ossietzky University of Oldenburg: naming of the University of Oldenburg after Carl von Ossietzky (1889-1938)

- ^ Document for the relief portrait in the Hamburg town hall.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ossietzky, Carl von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Murner, Thomas (pseudonym); Carasco, Simson (pseudonym); Celsus (pseudonym); Hemlock, Lucius (pseudonym); Yatagan (pseudonym) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German journalist, writer and pacifist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 3, 1889 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Hamburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 4, 1938 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Berlin |