Women's movement

The term women's movement (also women's rights movement ) describes a global social movement that advocates the equality and recognition of women in the state and in all areas of society. It arose in connection with the social and educational reform movements of the 19th century in Western Europe and the USA (→ life reform ) and quickly spread to other countries.

Important issues in the women's movement include: the gender equality and the revaluation of traditional gender roles , in particular in gender relations tutelage, injustices andeliminate social inequalities .

Philosophical basics

The first beginnings of a women's rights movement emerged in the Age of Enlightenment and the beginnings of bourgeois emancipation efforts at the beginning of the 18th century. The basic idea was the equality of all people, as it was proclaimed, for example, in the course of the French Revolution . With her Declaration of the droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne , Olympe de Gouges demanded the same rights and duties for women as early as 1791, shortly after the declaration of human and civil rights (1789). Because statements on human and civil rights only considered men at that time.

With regard to the relationship between the sexes, two fundamentally different views crystallized very early on: a dualistic or differentialistic and a generalistic or egalitarian perspective. The former was based on a fundamental, natural or justified by the new sciences “difference of the sexes”.

The egalitarian approach was based on the ideas of the Enlightenment. According to this, all people were “naturally equal”, from which the demand for gender equality in all areas of society was derived.

Modern women's rights movement

The modern women's rights movement can be divided into three waves:

- The first wave of the modern women's movement or women's rights movement (middle of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century) fought for the basic political and civil rights of women such as B. the right to vote for women , which was legally anchored in Germany in November 1918, the right to gainful employment , the right to education and for a society on a new moral basis .

- The second wave of the women's movement emerged in the 1960s as a criticism of the massive discrimination against women, especially mothers. The pent-up demand for equality for women gradually found state recognition. B. at the UN , which declared 1975 to be the International Year of Women . Because of their criticism of all previous forms of organized politics, at least large parts of the second phase from around 1968 also saw themselves as an autonomous women's movement . This second wave is often understood as part of the New Left and the new social movements . It makes sense, however, to look at the women's movement of the last two centuries in a context and differentiate according to phases or waves.

- In the 1990s, a third wave (third-wave feminism) of the women's movement emerged, especially in the USA , which continued the ideas of the second wave in a modified form. New aspects are above all a more global, less ethnocentric view , the emphasis on the necessity that masculinity is also a construct that differs according to time and region and that must be critically questioned. Under the concept of gender mainstreaming agreed in 1995 at the 4th UN World Conference on Women of the assembled governments incl. Vatican the smallest reform compromise on which they could agree, as a top-down strategy , the women but also lesbian and support gay movements.

Women's rights activist and women's rights are not just names for supporters of the older women's movement (1848-1933), but still popular. For members of the new women's movement since the 1960s, however, the terms feminist and feminist are more likely to be used. The Egyptian Qāsim Amīn was one of the male women's rights activists of the past .

First wave

In the course of the French Revolution , equality between men and women was also made a topic, first especially in the salons of Europe, but also among Old Catholics during the pre- March period . The derogatory term blue stocking referred to these intellectual circles .

The first wave of the women's movement in the USA came about in the course of the anti- slavery movement. The abolitionists also included many women, often religiously motivated. They realized that not only the rights of African Americans , but also those of women were inconsistent with the civil rights of Anglo-American men. So in 1848 the " Declaration of Sentiments " was passed, which was consciously based on the US Declaration of Independence and declared the equality of women and men and thus their rights. Above all, the right to vote for women and a reform of marriage and property law were called for.

The members of the first women's movement were called women's rights activists . As one of its main goals was women's suffrage, they were also (often pejoratively) as suffragettes ( suffrage - English suffrage, from Latin . Suffragium - vote) referred.

The main aspired goals of the first wave were:

- Right to gainful employment

- Right to education, see women's studies

- Right to active and passive political action, see women's suffrage

- a society on a new moral basis

In older research, a distinction was made between three currents for the German-speaking countries: the middle-class, moderate women's movement around Henriette Goldschmidt (1825–1920), Louise Otto-Peters (1819–1895), Auguste Schmidt (1833–1902), Helene Lange (1848–1920) 1930) and Gertrud Bäumer (1873–1954) with the General German Women's Association , the bourgeois radical women's movement around Minna Cauer (1841–1922) and Anita Augspurg (1857–1943) with the German Association for Women's Suffrage and the socialist women's movement around Clara Zetkin (1857-1933). This strict separation is considered to be out of date in recent research, since it makes more sense to differentiate between the main areas of engagement. The middle-class, moderate wing primarily advocated local voting rights and an improvement in educational opportunities for women as well as the recognition of gainful employment by women, often with a view to particularly disadvantaged professional groups (servants, actresses). The bourgeois-radical wing strove for full women's suffrage at the national level and the right of access to universities , sometimes together with the socialists. For the proletarian women's movement, the right to work hardly played a role; instead, the demands focused on improving working conditions, including equal pay for male and female factory workers. All wings were concerned with reshaping society on a new moral basis.

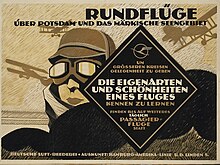

Poster : Hans Rudi Erdt ; " Kranich ": Otto Firle

From 1900 the birth rate fell significantly. Around 1910 it was just under 4; during the war it fell to 2; after a brief spike, it fell again in the direction of 2 (and also below it from the Great Depression in 1929). The lower number of children on average contributed to a change in the role of women with children.

During World War I, millions of women went to work to replace men who fought on one of the fronts of World War I. After 1918, millions of men were disabled and thus unable to work; many women became family breadwinners (see also First World War # Consequences of the war ). This war and the German inflation from 1914 to 1923 created a hitherto unknown social hardship among war orphans and widows . Since the first year of the war, women's protests increased, for example in the form of food riots , but also through the participation of women workers in mass strikes.

In 1918 the republic was proclaimed in Germany ; the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy became the republics of Austria and Hungary ; With the October Revolution in Russia, tsarism fell and Poland also became a republic . This resulted in numerous social changes, such as the right to vote for women introduced in Germany in 1919.

Especially in the short heyday from 1924 to 1929 ('golden twenties'), many social upheavals were visible.

Second wave

The trigger for the so-called second wave of the women's movement was a general social upheaval and change in values after the Golden Age of Marriage of the 1950s and 1960s. In Germany as in the USA, in the wake of the New Left within the framework of the Socialist German Student Union (SDS), it changed from a student movement to a social movement. In the United States, women were inspired by the African American civil rights movement and the mass movement against the Vietnam War to become more involved in solving their own problems.

The special characteristics of this women's movement were:

- Consciousness Raising : The development of the new group analytical format without a formal management structure of the Consciousness Raising group by the New York Radical Women , an early women's liberation group in New York City. The exchange of problems that were initially experienced individually is followed by the realization that these are widespread, which in turn raises questions about causes and possible solutions.

- Spectacular forms of action, including acts of civil disobedience , which were based on the forms of protest of other social movements and developed them further (see format of the Consciousness Raising group )

- Analysis of the causes of the injustice experienced as discrimination and violence ;

- Topics such as abortion (catchphrase: “My belly is mine”), sexuality, sexual abuse .

Even the Action Council for the Liberation of Women in 1968 formulated less “women's problems” than criticism of the hierarchical gender order, which was not questioned by the New Left either, and derived from this the temporarily necessary self-organization of women. This gave rise to the “autonomous” women's movement - but only years later.

Socialist Women's Association West Berlin (SFB)

The Action Council split into the Marxist- oriented Socialist Women's League West Berlin around Frigga Haug and many small groups. In a manifesto, Helke Sander demanded all attention for mothers and children and justified the separation. “The Marxist-oriented parliamentary group drafted a new position paper and from December 1970 gave itself a new name: Socialist Women's Association West Berlin (SFB). The SFB has now added the slogan 'Women and men are stronger' to the motto of the Action Council 'Women are strong together'. "

The SFB postulated in 1971: “We initially organize ourselves separately as women in order to find out the starting points for specific women agitation in theoretical work. We see this as a prerequisite for taking on our task in the class struggle under the leadership of the Communist Party ”.

The SFB vehemently opposed feminist positions. Therefore it should not be seen as a continuation of the Action Council for the Liberation of Women and also not a forerunner of the women's centers. Only years later did the SFB claim the terms “feminist” and “autonomous”.

Campaign against paragraph 218

As a result of the self- accusation campaign ' We have an abortion ', there were demonstrations and collections of signatures in several cities in Germany in 1971 against Paragraph 218, which makes abortion a punishable offense. With the slogans “Whether children or no children, we alone decide” and “My belly belongs to me”, women demanded the approval of the abortion.

Bread and roses

In 1971, Helke Sander gathered a few women who then jointly wrote the “Women's Handbook No. 1: Abortion and Contraceptives”, which was self-published. The first edition was 30,000. An interview with Helke Sander:

- “The manufacturers tested the contraceptive pills on Puerto Ricans and men who came into contact with estrogen during production and whose breasts grew. The Vatican was actually involved in the factories! I had already been given the pill in the 1960s, I was practically a guinea pig and suffered from heart pain - at the time I thought it was due to the bad marriage - in fact the estrogen in these pills was overdosed and many died from it. These pills were eventually banned. That is why we were also against the demand for 'pill on sickness certificate' raised by Frigga Haug and the SFB. We thought that harmless contraceptives should be developed first . (…) We didn't know anything about the American group ' Our Bodies, Ourselves ', whose book was written in 1971 on the same occasion with a similar result.

- In 1974, 'Bread and Roses' organized a big event at the TU where we reported doctors for illegal abortions. Especially one with the nickname 'golden curette ' - who was officially very strictly against abortion. Another was over 80 and half blind, but continued to do abortions - all scandalous doctors. Although it was an official offense, our complaint was not followed up. "

In 1972 Helke Sander, together with Sarah Schumann and camerawoman Gisela Tuchtenhagen, realized the documentary "Makes the pill free?"

Women's centers

The women's center in West Berlin was opened in March 1973 - the first in the German-speaking area. With its non-hierarchical structure and non-dogmatic orientation, it differed fundamentally from all previous women's groups and for the first time offered a place, its own, women-identified, autonomous and grassroots democratic center.

Autonomous and grassroots democracy

For the autonomous women's movement, autonomous means independence from all forms of traditional and new left-wing politics (and in defeat from the “Socialist Women's Association”), but also independence from parties, institutions and “state dough” - all projects were self-sufficient until 1976 (first women's refuge ) financed. In contrast to the orthodox ( DKP ) and Maoist left acting at the same time , the autonomous women's movement relied on consensus and grassroots democracy , replaced “training” with self- education , and the “party line” with diversity of opinion . The women's centers, which were established in rapid succession in many cities in West Germany from 1973 onwards, worked according to this model. Based on these same autonomous, grassroots democratic structures, the movement of citizens' initiatives grew rapidly; both together changed West German society from the ground up in the 1970s.

Identified women

When the centers and projects were founded, lesbians were the driving force because - as they postulated - they did not lose any energy in relationships with men and “because they simply love women”. One straight woman recalls:

- “At first we had a lot of respect and interest for each other. In every group, including the § 218 group, there were very many lesbians. (…) We all drove away from one another because we felt our strength, there was something erotic about it: there come together seventy women who have all been waiting and all been looking in a certain direction, and then suddenly they find seventy others who want the same thing. A sudden sense of community from an experience of great isolation. "Women are strong together" expresses this common feeling of strength, the feeling of being able to change [our situation] together, exuberance in the feeling of strength! "

Communication channels

From 1973 to 1976 the women's centers exchanged ideas and experiences with one another by means of a 'women's newspaper' - a self-typed organ with rotating editorial staff - and from 1975 also by means of a 'women's yearbook' and a 'women's calendar'. Women's groups of all stripes met for congresses, including in Frankfurt 1972, Munich 1973, Coburg 1973, from 1971 for the Femø Women's Camp, in Brussels 1976 for the International Tribunal on Violence against Women . As early as 1972, lesbian groups met annually for the Whitsun meeting, later called the Lesbian Spring Meeting (LFT). Women's festivals played an important role, at which the women's rock band Flying Lesbians played in many cities from 1974 to 1977. From 1976 to 1983, the Summer University for Women with thousands of participants ensured professional exchange. In 1976 the magazines Courage and EMMA took over the communication between interested parties and women's projects. Now women's centers lost their importance as incubators, the movement was already too big for a “shop”.

Projects of the autonomous women's movement

Advice on abortion and organizing “Holland trips” to abortion clinics initially tied up a lot of energy in the women's centers. Various projects soon emerged from working groups: women's health centers, psychological counseling, women's shelters , emergency calls and advice for women and girls affected by violence, courses in self-defense . There were teachers, university lecturers, artists, musicians, women in the natural sciences and media professionals in professionally oriented groups. They founded magazines, publishers, a book distribution company, a printing company, women's pubs and, in many places, women's bookshops.

As an example, see also: Women's Center West Berlin , Lesbian Action Center West Berlin .

Men's movement

In response to the women's movement, a men's movement developed from the late 1960s . Today this has partly reactionary masculist traits, currents within this regard feminism as an enemy image and are part of the conservative " backlash " of the 1980s. However, since the 1960s there have also been groups of men who are trying to find a new self-image that incorporates findings from gender and men research . Owing to the weakness of the critical approach within the men's movement in Germany, men's research and practical work with boys only developed here with a long delay.

Third wave

In the 1990s, a third wave of the women's movement developed in the United States. It was a reaction to popular anti-feminism and the view that feminism was obsolete because it had achieved all of its goals. Some also see the emergence of the third wave as an answer to internal feminist debates such as the Feminist Sex Wars . The term "third wave" ( third-wave feminism ) came up in the first half of the 1990s and goes back to Rebecca Walker , who a few years later (1997) co-founded the Third Wave Foundation .

The third wave of feminism is very much oriented towards the goals of the second phase, which it still does not see realized today. Alleged or actual errors of radical and cultural second wave feminism, such as: B. ethnocentrism and (partial) exclusion of men, should be corrected and feminism adapted to current social conditions. In addition, it is about questioning problematic identity concepts, gender identity and sexuality .

Above all, it is a generation change. Feminism as a term is up for grabs, for some younger women it is considered homely and “uncool” because they do not identify with the feminists of the past decades. On the other hand, many young women see a equality of the sexes still far from being achieved and look at the previous generation feminists as an important political pioneers and the concept of feminism continues to be politically necessary. This is how, among other things, the riot grrrls in the US from a punk context. Elements of the Riot Grrrl movement were also taken up in Germany. The young feminists of the third wave work primarily with the Internet and in a goal-oriented manner in projects and networks with a feminist orientation, e.g. B. in the Third Wave Foundation (USA) or with specific projects such as Ladyfests . By appropriating internet media, women and women's organizations network across national and cultural borders; form translocal networks through which they support each other in their local work and concerns and jointly pursue advocacy policy.

See also

- Christian women's movement

- Women in Politics , Women20 (W20)

- Kyriarchat

- Men's movement

- Proletarian women's movement

Women's movement in individual countries:

- Feminism in Japan

- Women's movement in Egypt

- Women's movement in Germany : women's suffrage movement in Germany , Bremen women's movement , women's center West Berlin , Lesbian Action Center West Berlin

- Swiss women's movement

- List of women's networks in Germany

literature

Generally

- Antoinette Burton: History is Now: feminist theory and the production of historical feminisms. In: Women's History Review. Volume 1, No. 1, 1992, pp. 25-39 - the construction of the story (s) of feminism.

- Anke Domscheit-Berg : Tear down walls! Because I believe we can change the world. Heyne, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-453-20042-5 .

- Stefanie Ehmsen: The march of the women's movement through the institutions: The United States and the Federal Republic in comparison. Westphalian steam boat, Münster 2008.

- Margarete Grandner, Edith Saurer (ed.): Gender, religion and engagement. The Jewish women's movements in German-speaking countries. 19th and early 20th centuries. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2005, ISBN 3-205-77259-8 , pp. 79-101.

- Antonia Meiners (Ed.): Kluge Mädchen: Or how we became what we shouldn't become. Sandmann, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-938045-56-5 .

- Reimar Oltmanns : Vive la Française! The silent revolution of women in France. Rasch and Röhring, Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-89136-523-3 .

- Ute Planert (Ed.): Nation, Politics and Gender. Women's Movements and Nationalism in the Modern Age. Campus, Frankfurt am Main / New York, NY 2000, ISBN 3-593-36578-2 .

- Hedwig Richter , Kerstin Wolff (Ed.): Women's suffrage. Democratization of democracy in Germany and Europe. Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2018.

- Renate Reimann: Women on the barricades. Courageous steps on the long road to equality. In: Einst und Jetzt (= yearbook of the Association for Corporate Student History Research ). Würzburg 2002, pp. 193-226.

- Hannelore Schröder: Unruly - rebels - suffragettes. Feminist awakening in England and Germany. One-subject, Aachen 2001, ISBN 3-928089-30-7 .

- Petra Unger: Women's choice right. A brief history of the Austrian women's movement. Mandelbaum, Vienna 2019, ISBN 978-3-85476-688-9 .

History of literature and ideas and the history of the women's movement

- Self-publishing for women: Witches whispering, women are reaching out to self-help. Berlin 1975.

- Miriam Gebhardt: Alice in no man's land. How the German women's movement lost women. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Munich 2012, ISBN 978-3-421-04411-2 .

- Ute Gerhard : women's movement and feminism. A story since 1789. Beck-Verlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-56263-1 .

- Florence Hervé (ed.): History of the German women's movement. 7th, improved and revised edition. PapyRossa , Cologne 2001, ISBN 3-89438-084-5 .

- Sigrid Kannengießer: Translocal empowerment communication. Media, globalization, women's organizations. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2014, ISBN 978-3-658-01802-3 .

- Margret Karsch: Feminism for those in a hurry. Construction Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-7466-2067-8 .

- Elsbeth Krukenberg-Conze : The women's movement, its goals and its meaning. Mohr Verlag, Tübingen 1905.

- Ilse Lenz : The New Women's Movement in Germany. Farewell to the small difference. A collection of sources. 2nd Edition. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-17436-5 .

- Gerda Lerner : The emergence of feminist consciousness. From the Middle Ages to the First Women's Movement. dtv, 1998, ISBN 3-423-30642-4 .

- Rosemarie Nave-Herz : The History of the Women's Movement in Germany. Leske + Budrich Verlag, 1994, ISBN 3-8100-1250-5 .

- Herrad Schenk : The feminist challenge. 150 years of the women's movement in Germany. ISBN 3-406-06013-7 .

- Heinrich Böll Foundation , Feminist Institute (ed.): How far did the tomato fly? A gala of reflection for women in 1968. Berlin 1999, (With contributions by Seyran Ates , Halina Bendkowski , Christina von Braun , Erica Fischer , Frigga Haug , Cristina Perincioli , Cäcilia (Cillie) Rentmeister , Helke Sander , Marlene Streeruwitz ).

- Kristina Schulz: The long breath of provocation. The women's movement in Germany and France 1968–1976. Frankfurt 2002, ISBN 3-593-37110-3 .

To the second wave

- Ilse Lenz (ed.): The new women's movement in Germany. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-17436-5 .

- Annette Kuhn (Ed.): The Chronicle of Women. Dortmund 1992, ISBN 3-611-00195-3 .

- Cäcilia (Cillie) Rentmeister : Women's worlds - distant, past, strange? The Matriarchy Debate and the New Women's Movement. In: Ina-Maria Greverus et al. (Hrsg.): Kulturkontakt, Kulturkonflikt: To the experience of the foreign. Volume 2, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-923992-26-2 .

- Cristina Perincioli : Berlin is becoming feminist. The best that remained of the 1968 movement . Querverlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-89656-232-6 .

On third wave feminism

- Jennifer Baumgardner, Amy Richards : Manifesta: Young Women, Feminism, and the Future. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000, ISBN 0-374-52622-2 . (English, about the Third Wave in the USA with a historical review)

- Jennifer Baumgardner, Amy Richards, Winona LaDuke: Grassroots: A Field Guide for Feminist Activism. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005, ISBN 0-374-52865-9 . (English)

- Leslie Heywood, Jennifer Drake (Eds.): Third Wave Agenda: Being Feminist, Doing Feminism. University of Minnesota Press, 1997, ISBN 0-8166-3005-4 . (English)

Web links

- www.addf-kassel.de Foundation archive of the German women's movement in Kassel

- Library and archive of the Women's Research, Education and Information Center (FFBIZ)

- FrauenMediaTurm (FMT) , information center on the history of emancipation

- www.onb.ac.at/ariadne Online project about the Austrian women's movement

- Federal Commission for Women's Issues (EKF): Women Power History 1848–2000 (chronology of the history of women and equality in Switzerland). (several small PDFs) Retrieved August 25, 2010 .

- www.hhi-bremen.de Research and publications on the history of the women's movement, women's education, social policy and the history of Jewish women scholars

- Women's movement / gender politics full texts in the library of the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Bonn

- Federal Agency for Civic Education: Women's Movement (Dossier)

- bpb.de

- Chronicle of the new women's movement on the women's media tower website, from 1973

- Bavarian writers and the bourgeois women's movement around 1900 Exhibition with documents and correspondence in the culture portal bavarikon

Sources and Notes

- ↑ U. Gerhard: Women's Movement and Feminism. A story since 1789. Munich 2009, p. 6.

- ↑ The term “women's rights activist” in the present: tagesschau.de November 29, 2006 ( Memento from July 31, 2010 on WebCite ) - taz.de September 26, 2006 - tagesspiegel.de September 3, 2006 - PR Newswire January 4, 2006

- ^ Charles C. Adams: Islam and Modernism in Egypt. 2nd Edition. Russell & Russell, New York 1968, pp. 231-235.

- ^ Howard Zinn: A People's History of the United States. Harper Perennial, 2005, ISBN 0-06-083865-5 , p. 123.

- ^ André Böttger: Women's suffrage in Germany. In: Marjaliisa Hentilö, Alexander Schug (ed.): “From today for everyone!” One hundred years of women's suffrage. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, 2006.

- ↑ Germany in demographic change. 2005 edition (PDF), see graphic on the left on p. 15: The decline in birth rates in Germany (publisher: Rostock Center for Research into Demographic Change)

- ↑ see also Barbara Beuys: Die neue Frauen - Revolution im Kaiserreich. Hanser Verlage, 2014, ISBN 978-3-446-24491-7 .

- ^ Gerhard Hirschfeld , Gerd Krumeich , Irina Renz (eds.): Encyclopedia First World War. Paderborn 2009, ISBN 978-3-506-76578-9 , p. 663 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Veronika Helfert: Violence and gender in unorganized forms of protest in Vienna during the First World War. In: Yearbook for research on the history of the labor movement . Issue II / 2014; as well as Irena Selisnik, Ana Cergol Paradiz, Ziga Koncilija: Women's protests in the Slovene-speaking regions of Austria-Hungary before and during the First World War. In: Work - Movement - History . Issue II / 2016.

- ↑ Cristina Perincioli: Berlin is becoming feminist. The best that remained of the 1968 movement . Querverlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-89656-232-6 , p. 155.

- ↑ Pelagea. Berlin materials on women's emancipation . Published by the Socialist Women's Association West Berlin (SFB) 2/1971.

- ↑ Frigga Haug: Defense of the women's movement against feminism. In: The argument. Volume 15, H. 83, 1973, ISSN 0004-1157

- ↑ Cristina Perincioli: Berlin is becoming feminist. The best that remained of the 1968 movement . Querverlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-89656-232-6 , p. 158.

- ↑ Annette Kuhn (Ed.): The Chronicle of Women. Dortmund 1992, ISBN 3-611-00195-3 , p. 577.

- ↑ Documents of "Aktion 218", which worked in several cities, can be found in Ilse Lenz (Ed.): The New Women's Movement in Germany. VS Verlag, Wiesbaden 2010, ISBN 978-3-531-17436-5 , pp. 67-84.

- ↑ Annette Kuhn (Ed.): The Chronicle of Women. Dortmund 1992, ISBN 3-611-00195-3 , p. 583.

- ↑ quoted from Cristina Perincioli : Berlin is becoming feminist. The best that remained of the 1968 movement. Querverlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-89656-232-6 , p. 199.

- ↑ The film "Makes the pill free?" From 1972 is being awarded today by Studio Hamburg.

- ↑ Cristina Perincioli: Berlin is becoming feminist. The best that remained of the 1968 movement. Querverlag, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-89656-232-6 , p. 126.

- ↑ Like the district and children's shops, women's centers had often rented former ' mom and pop shops '.

- ↑ Annette Kuhn (Ed.): The Chronicle of Women. Dortmund 1992, ISBN 3-611-00195-3 , pp. 579, 588-592.

- ↑ Antje Schrupp: Third Wave Feminism