Olympe de Gouges

Olympe de Gouges (actually Marie Gouze; born May 7, 1748 in Montauban , † November 3, 1793 in Paris ) was a revolutionary , suffragette , writer and author of plays in the Age of Enlightenment . She is the author of the Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens of 1791.

life and work

childhood

Marie Gouze was born in Montauban in the southern French province of Quercy (in what is now the Tarn-et-Garonne department ) and spent her youth there. Her mother, the laundress Anne-Olympe Mouisset, had been married to the butcher Pierre Gouze since 1756, but he was not Marie's biological father. It is more likely that she came from a relationship between her mother and Jean-Jacques Lefranc, Marquis de Pompignan , a wealthy country nobility and well-known adversary of Voltaire . This was relieved of any legal father duty for his "bastard" daughter. The Catholic Pompignan did not feel obliged to support mother and daughter materially, according to the moral standards of the time.

marriage

At the age of 17 Marie Gouze was married - against her will - to the Parisian landlord Louis-Yves Aubry, who was able to open an inn thanks to her dowry . Their son Pierre was born in 1766 . Her husband soon died, likely in a flood of the Tarn . The young widow Aubry moved to Paris, where sister and brother-in-law had already settled. She did not marry a second time; all that is known is a free, long-term relationship with Jacques Biétrix de Rozières , heir to a privilege on military transports.

Creative phase

In the 18th century there was seldom reading and writing skills among the general public ; women in particular received little education. Then there were Marie Gouze's unhappy family circumstances. It can therefore be assumed that she was only able to acquire basic reading and writing skills in her childhood. Occitan was also spoken in their homeland, and northern French was not in use here. She used the years between her arrival in Paris (around 1768) and the point in time when she submitted her first play to a stage (1784) for intensive self-study: cultivating French through conversation, reading literary and political writings, going to the theater and finally own literary attempts. As early as 1774 , the Enlightenment woman wrote a memorandum that turned against slavery . Because of the controversial subject and the gender of the author, the book was not published until after the revolution in 1789.

In 1786, under a pseudonym, her epistolary novel Memoirs of Madame Valmont about the ingratitude and cruelty of the Flaucourt family towards theirs , her covert autobiography, in which she a. a. Criticized the treatment of unmarried mothers and their "bastard" children and wrote on divorce law and the right to have sexual relations outside of marriage. These writings already showed their feminist standpoint, which was directed against the pseudo morals of their time.

As the stage name Olympe de Gouges, with which she signed many of her texts, she used the first name of her mother and a modified form of her family name, which her sister Jeanne Gouges also used. She found access to circles of the Frondeur opposition, which gathered under the protection of opposition princes; one such enclave was the Palais Royal , where Philippe Égalité, Duke of Orléans , resided and where Madame de Gouges very likely met Louis-Sébastien Mercier .

The French revolution

In 1785 the author submitted her play Zamore et Mirza to the Comédie Française , which addressed slavery in the colonies. As a result, she was embroiled in intrigues and slander for years and was even imprisoned in the Bastille . The explosive piece only had its premiere in December 1789 and caused quite a stir politically before it was temporarily removed from the program.

From the beginning de Gouges was confronted with hostility from various political directions, which irritated the fact that a “femme auteur” dared to make public appearances with serious literary plays of political content. Misogynist critics discredited and defamed many well-known women like M me de Staël , M me Roland , Mary Wollstonecraft and also this author. Despite slander and great difficulties, de Gouges was versatile and productive: in 1793 her works appeared in two volumes.

During the revolution , Olympe de Gouges became a passionate advocate of women's human rights , civil rights. With a few exceptions, such as Nicolas de Condorcet , who has long advocated women's rights, the revolutionaries excluded the female half of the population. During these years, Olympe de Gouges published many political texts on current events, which she printed and distributed in the form of brochures, leaflets and posters.

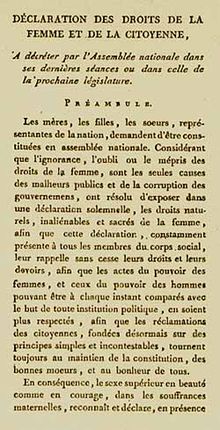

Manifesto on the rights of women and citizens

It was not until 1791 that she wrote the Declaration des droits de la Femme et de la Citoyenne ( Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens ) in great haste , which is to be understood as a protest against the male privileges that were now elevated to constitutional status. Her feminist-revolutionary “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens” was still in print when the male-dominated bourgeois constitution had already been adopted and France had become a constitutional monarchy .

At the time of the political victory of the Third Estate and with it the idea of legal equality for all men, a new, radical proclamation of freedom and equality for the female people was made to the government and the members of parliament. Since the sovereign excluded all women from popular sovereignty , Olympe de Gouges called the new regime tyranny . On behalf of the nation's mothers, daughters and sisters, she called on the National Assembly to adopt its declaration of the rights of women and citizens , the recognition of private and political civil rights, as soon as possible. She demanded this new, universal-egalitarian constitution, because the one that had just come into force was illegitimate and null and void because the female people were not represented and not even involved in drafting it.

The document consists of several parts, published in September 1791 under the title "The Rights of Women" :

- Letter to the queen

- The rights of women (invocation: "Man are you able to be just ...")

- Declaration on the Rights of Women and Citizens (to the National Assembly)

- preamble

- Articles I to XVII

- Postamble

- Form of the social contract between man and woman

- Two postscripts

Excerpt: "The superior sex in terms of beauty and courage, the hardships of motherhood ... explains the following rights of women and citizens:

Article 1: The woman is born free and remains the same as the man in all rights. The social differences can only be based on general utility. ...

Article 4: Freedom and justice are based on the fact that the other is rewarded for what is due to him. Thus, in exercising her natural rights, women only come up against the limits imposed by the tyranny of men; these must be redrawn by the laws dictated by nature and reason. ...

Article 6: The law should be the expression of the will of all; all citizens should contribute to its creation personally or through their representatives. ...

Article 10:… The woman has the right to climb the scaffold . Likewise, she must be granted the right to mount a speaker's platform. ...

Article 13:… The woman is drawn on indiscriminately for labor and onerous duties and must therefore be taken into account when assigning positions and dignities, in lower and higher offices as well as in trade .

Article 16: ... the constitution is null and void because the majority of the population ... did not participate in its drafting. "

Olympe de Gouges has attached a social contract reminiscent of Rousseau , in which marriage rights were regulated on an equal basis. In the afterword, she calls on women to study philosophy and pursue the ideas of the Enlightenment.

Arrest and death sentence

Arrested in the summer of 1793 at the time of Robespierre's reign of terror and charged as a royalist, Olympe de Gouges was incarcerated for months in various revolutionary prisons. The public prosecutor Antoine Fouquier-Tinville made short work of her before the special court for politically dissenters, the Revolutionary Tribunal . The historian Karl Heinz Burmeister states: “Their inclination towards the Girondists , their commitment to federalism and the monarchy , their opposition to the Jacobins , their personal hostility to Robespierre , had led to their execution ; but she also atone for her commitment to women's rights. One felt an undesirable interference in the politics reserved for men. "

While in custody she wrote to the tribunal:

“Undaunted, armed with the weapons of honesty, I face you and demand an account of your cruel activities, which are directed against the true pillars of the fatherland. (...) Isn't Article 11 of the Constitution anchored freedom of expression and the freedom of the press as the most precious human good? Would these laws and rights, indeed the whole constitution, be nothing more than hollow phrases, devoid of all meaning? Woe to me, I had this sad experience. "

The death sentence was carried out by guillotine on November 3, 1793 on Place de la Concorde .

Descendants

According to Olivier Blanc, her son Pierre Aubry de Gouges (officer in the Rhine Army from 1793 ) emigrated to Guyana with his wife and five children after the death of Olympus . After his death in 1802, his wife tried to return to France, but died during the voyage. The two daughters Marie Hyacinthe Geneviève de Gouges (the English officer Captain William Wood) and Charlotte de Gouges (the American politician Robert S. Garnett ) married in Guadeloupe , so that descendants of Olympe de Gouges still live today.

Quotes

“Man, are you even able to be fair? [...] Can you tell me who gave you the absolute power to oppress members of our sex? […] Look at the Creator in his wisdom, […] consider the sexes in the order of nature. […] Only the man […] wants in this century of enlightenment and clear understanding in ignorance that can no longer be justified despotically to rule over a sex that has all intellectual abilities. He claims to use the revolution for himself and to demand his rights to equality, to say only so much. "

Honors

- May 1998 Placement of a commemorative plaque 20, rue Servandoni, Paris

- November 1998 A memorial plaque is installed on the house where he was born in Montauban

- The Olympe de Gouges Prize has been awarded by the Working Group of Social Democratic Women (ARSP) since 2001

- In 2004 the "Place Olympe de Gouges" was named in the 3rd arrondissement of Paris

- In May 2012, the newly founded Tübingen Academic Women's Association Olympea was named after Olympe de Gouges.

- In October 2013, de Gouges was one of the two candidates that French President François Hollande wanted to propose for transfer to the Paris Panthéon .

swell

- Olympe de Gouges: Mother of human rights for women , edited and commented by Hannelore Schröder , Aachen 2000.

- Olympe de Gouges: Man and Citizen: The Rights of Women, Paris 1791 (with full source text in French / German). Edited and commented by Hannelore Schröder, Ein-Fach, Aachen 1995, ISBN 3-928089-08-0 .

- Olympe de Gouges: The woman was born free. Texts on women's emancipation, 1789–1870, Volume I, edited and commented on by Hannelore Schröder, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-406-06001-3 ; Volume II. 1981, ISBN 3-406-06031-5

- Luise F. Pusch , Susanne Gretter (eds.): Famous Women: 300 Portraits, Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1999, p. 111, ISBN 3-458-16949-0 .

literature

Primary literature (original)

- Olympe de Gouges: Declaration of the Droits de la femme et de la citoyenne suivi de Préface pour les Dames ou Le Portrait des femmes. Afterword by Emanuèle Gaulier, Éditions Mille et Une Nuits 2003, ISBN 978-2-84205-746-6 .

Writings by Olympe de Gouges in German translation

- The woman is born free. Texts on women's emancipation, 1789–1870, Volume I, edited and commented by Hannelore Schröder, CH Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-06001-3 .

- Memorandum of Madame de Valmont. / Mémoire de Madame de Valmont. (1788) Edited by Gisela Thiele-Knobloch, Helmer, Frankfurt am Main 1993, ISBN 3-927164-44-5 .

- Person and citizen. "Women's Rights". (1791), published by Hannelore Schröder, ein-fach-verlag, Aachen 1995, ISBN 3-928089-08-0 .

- The rights of women 1791. Published by Karl Heinz Burmeister , Wallstein, 2003, ISBN 978-3-89244-736-8 .

- Women's Rights and Other Scriptures. / Les droits de la femme. Published by Gabriela Wachter, Parthas, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-86601-273-8 .

- The philosophical prince. Story from the East, translated, edited and commented by Viktoria Frysak and Corinne Walter, Edition Viktoria, Vienna 2010, ISBN 978-3-902591-03-6 .

- Fonts. Published by Monika Dillier, Stroemfeld, Basel / Roter Stern, Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-87877-147-9 .

- Molière at Ninon or The Century of the Great Men, translated, edited and commented by Viktoria Frysak, Edition Viktoria, Vienna 2013, ISBN 978-3-902591-04-3 .

- Women's rights / Declaration of the droits de la femme. Edited, translated and with an introduction by Gisela Bock , dtv Verlagsgesellschaft, Munich 2018, ISBN 978-3-423-28982-5 (bilingual edition in the dtv library series )

Secondary literature

- Sophie Mousset: Women's Rights and the French Revolution. A Biography of Olympe de Gouges. Transaction Publ, 2006, ISBN 978-0-7658-0345-0 (on Google Books : large parts of it can be read and searched online)

- Gerlinde Kraus: important French women. Schröder, Mühlheim am Main & Norderstedt 2007, ISBN 978-3-9811251-0-8

- Olivier Blanc: Marie-Olympe de Gouges, Une humaniste à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Editions René Viénet, Cahors 2003, ISBN 2-8498-3000-3 (French).

- ders .: Olympe de Gouges . Promedia, Vienna 1989, ISBN 3-900478-31-7 .

- Lottemi Doormann: A fire burns inside me. The life story of the Olympe de Gouges. Beltz, 2003, ISBN 978-3-407-80725-0 .

- Paul Noack : Olympe de Gouges, 1748–1793. Courtesan and campaigner for women's rights. DTV, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-423-30319-0 .

- Hannelore Schröder: Human rights for women. ein-fach-verlag, Aachen 2000 ISBN 3-928089-23-4 .

- Salomé Kestenholz: Equality in front of the scaffold. Portraits of French revolutionaries. dtv 1988 & Luchterhand, Darmstadt 1991, ISBN 3-630-61818-9 .

- José-Louis Bocquet, Catel Muller (Illustrator): The woman was born free - Olympe de Gouges. Splitter, Bielefeld 2013, ISBN 978-3-86869-561-8 .

- Eduard Maria Oettinger (arr.): Jules Michelet : The women of the French Revolution. Leipzig 1854, pp. 103-109 online

Web links

- Literature by and about Olympe de Gouges in the catalog of the German National Library

- Olympe de Gouges. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

- Current research on the work of Olympe de Gouges'

- Olympe-de-Gouges-Stiftung, human rights for women in creation

- Portrait of Mme Gouges on dadalos.org (International UNESCO Education Server for Democracy, Peace and Human Rights Education)

- Olympe de Gouges (1748–1793) "Woman is born free and remains the same as man in all rights." In: FrauenMediaTurm

- René Viénet: Olympe de Gouges, a Daughter of Quercy on her Way to the Panthéon in: La Semaine du Lot, no.273, November 3, 2001 (English)

- Olympe de Gouges executed twice, by Iring Fetscher, in: Die Zeit , No. 11, March 6, 1988

- Pauline Paul: For the right to oneself, in: Die Zeit, No. 31, July 27, 1990

- Olympe-de-Gouges website of Dr. Viktoria Frysak, Vienna

- Manfred Geier : Gouges, Olympe de , in: Kurt Groenewold , Alexander Ignor, Arnd Koch (Hrsg.): Lexicon of Political Criminal Trials , online, as of July 2017.

Declaration of the droits de la femme et de la citoyenne

- Original French text of the Declaration of the Droits de la femme et de la citoyenne

- German translation of the declaration of the rights of women and citizens

- Annotated comparison of the declarations from 1789 and 1791

- Draft articles of association for spouses ("Contrat social")

Individual evidence

- ↑ Although Condorcet became an ardent supporter of the revolution in the 1790s, possibly because of his aristocratic origins, perhaps also because of political sympathies with Mme de Gouge - since he himself had also repeatedly pleaded for equal rights beyond gender boundaries, for example also in education / Education -, himself thrown into prison and died there in unknown circumstances

- ^ Karl Heinz Burmeister: Olympe de Gouges. The rights of women 1791. Stämpfli Verlag, Bern 1999, p. 8

- ↑ This refers to Article 11 of the Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen de 1789 , which the constitution of 1791 preceded by

- ↑ cit. according to: Manfred Geier : Enlightenment. The European project. Reinbek b. Hamburg 2012, p. 329.

- ↑ Olivier Blanc: Marie-Olympe de Gouges ( French ). Editions René Viénet, Paris 2003.

- ↑ Olympe de Gouges, Montauban May 7, 1748 - November 3, 1793 Paris

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gouges, Olympe de |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gouze, Marie (real name); Gouges, Marie Olympe de; DeGouges, Olimpe |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French revolutionary and women's rights activist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 7, 1748 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Montauban |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 3, 1793 |

| Place of death | Paris |