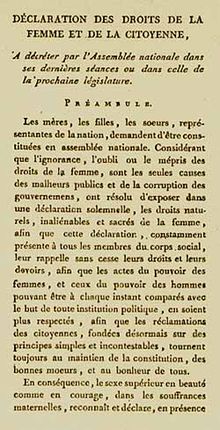

Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens

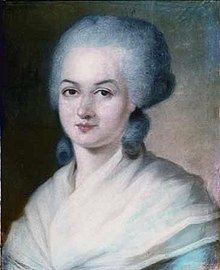

The Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens ( French Déclaration des droits de la femme et de la citoyenne ) was drafted on September 5, 1791 by the French suffragette, Olympe de Gouges , to be submitted to the French National Assembly for approval. In it she called for full legal, political and social equality for women .

The writing was a response to the Declaration of Human and Citizens' Rights that had been promulgated on August 26, 1789, shortly after the start of the French Revolution . However, the rights and obligations contained therein only applied to “responsible citizens”. Responsible citizens were only defined as men up to this point in time (September 1791). Women had no right to vote (they did not get this in France until 1944), no access to public office , no freedom of occupation, no property rights and no conscription . The declaration of the rights of women and citizens was the basis for the later introduction of women's suffrage in Europe .

content

structure

- Letter to the queen

- Women's rights ("Man, are you able to be just?")

- Declaration on the Rights of Women and Citizens (to the National Assembly)

- preamble

- Articles I to XVII

- Postamble

- Form of the social contract between man and woman

- Two postscripts

Extract from the declaration of the rights of women and citizens

- Art. I: Woman is born free and remains the same as man in rights [...]

- Art. II: The aim of every political association is the preservation of the natural and non-statute-barred rights of women and men: these rights are freedom, property, security and, above all, resistance to oppression.

- Art. III: The basis of any state power rests in its essence in the nation, which is nothing other than the reunification of women and men [...]

- Art. IV: Freedom and justice consist in giving back everything that belongs to another. Thus the exercise of woman's natural rights has no limit except those opposed to her by the constant tyranny of man. These boundaries must be reformed by the laws of nature and reason.

- Art. V: The laws of nature and reason prohibit all actions that can be harmful to society. Anything that is not prohibited by these wise and divine laws cannot be prevented [...]

- Art. VI: The law must be an expression of the collective will; all citizens must contribute to its creation personally or through a representative: all citizens who are equal in his eyes must be equally admitted to all dignities, positions and public offices [...]

- Art. VII: No woman is exempt; she will be charged, arrested and detained in the cases determined by law. Women, like men, are subject to this inexorable law.

- Art. VIII: The law may only stipulate penalties that are absolutely and obviously necessary [...]

- Art. IX: The full severity of the law is applied to every woman found guilty.

- Art. X: Nobody may be prosecuted because of their convictions, even if they are of a fundamental nature. The woman has the right to climb the scaffold; she must also have the right to climb into the stands [...]

- Art. XI: The free expression of thoughts and opinions is one of the most precious rights of women, since this freedom ensures the legitimacy of fathers towards children. Every citizen can therefore freely say: "I am the mother of a child who belongs to you" without being forced by barbaric prejudice to hide the truth [...]

- Art. XII: The guarantee of the rights of women and citizens must be committed to greater benefit. This guarantee must be based on the benefit of all and not on the particular benefit of those to whom it is granted.

- Art. XIII: For the maintenance of the state power and for the expenses of the administration, the contributions of women and men are equal. She is involved in all labor and hard work; It must therefore be equally involved in the distribution of posts, employment, orders, dignities and trades.

- Art. XIV: The citizens have the right to determine the necessity of the public tax themselves or through their representatives. Citizens can only agree to this if an equal division is permitted, not only for assets, but also for public offices, and if they have a say in the amount, assessment, collection and duration of taxation.

- Art. XV: The mass of women, united with that of men through tax payments, has the right to demand an account of their administration from any public official.

- Art. XVI: Any society in which the guarantee of rights is not guaranteed and the separation of powers is not established has no constitution at all. The constitution is null and void unless the majority of the individuals who make up the nation have participated in its drafting.

- Art. XVII: Property belongs to all genders, jointly or separately [...] nobody can be deprived of it as a true inheritance of nature [...]

Meaning and effect

The Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens, which is closely based on the Declaration of Human and Civil Rights of 1789 and which consists of a preamble and 17 articles (plus introduction and epilogue), was not simply an alternative for women, even if these are referred to in the preamble as the “superior sex in both beauty and courage”. In many cases it becomes clear that it is about both sexes who together make up the nation (Art. III). In many places, Olympe de Gouges replaced the word “l'homme” (human being / man) with the words “woman and man”, so that both genders became clear. Article VII states that there are no special rights for women.

While the demands for freedom, equality, security, the right to property and the right to resist oppression are largely the same in both declarations (Articles I and II), de Gouges' concept of freedom differs from the “negative” definition of 1789 (“The Freedom consists in being able to do everything that does not harm another. "). Article IV says: "Freedom and justice consists in giving back to others what is due to them."

De Gouges' basic view is that equal duties and equal rights must correspond. This is the most famous sentence from her declaration: “A woman has the right to climb the scaffold; they must also have the right to climb the stands […] ”(Art. X).

The historical significance of the Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens lies in the fact that it is the first universal declaration of human rights that makes universal claims for men and women. This also reflects the critical examination of the Enlightenment with the existing social order.

Various positions can be found in the literature on the history of the impact. While on the one hand it is pointed out that the declaration of 1791 only appeared in five copies and was politically completely ignored, on the other hand it says: "The declaration caused a sensation throughout France and even abroad." The first assumption is that de Gouges' explanation is still missing in most collections and lists of legal historical documents. In 1972 the text, which until then had been in the French national library, was rediscovered by Hannelore Schröder and published in German in 1977.

literature

- Olympe de Gouges: writings . 2nd edition, Stroemfeld / Roter Stern, Basel / Frankfurt am Main 1989, ISBN 3-87877-147-9 .

- Gisela Bock: Women's rights as human rights. Olympe de Gouges' “Declaration of the Rights of Women and Citizens” Contribution to the thematic focus “European History - Gender History” . In: European History Thematic Portal . 2009 ( clio-online.de [accessed on July 22, 2018]). Republished in: Gisela Bock: Women's rights as human rights: Olympe de Gouges' transnational rediscovery . In: Gisela Bock (ed.): Gender stories of the modern age. Ideas, Politics, Practice (= Critical Studies in History . Volume 213 ). Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-525-37033-9 , pp. 155-167 .

- Viktoria Frysak: Thought and work of the Olympe de Gouges (1748–1793) . Dissertation. University of Vienna, Vienna 2010 ( univie.ac.at [accessed July 24, 2018]).

- Birgit Menzel: Women and Human Rights. Historical development of a difference and approaches to eliminate it . IKO, Frankfurt am Main 1994, ISBN 3-88939-602-X .

- Hannelore Schröder: Olympe de Gouges' "Declaration of the rights of women and citizens" (1791) . In: Herta Nagl-Docekal (Ed.): Feminist Philosophy (= Vienna series . Volume 4 ). Oldenbourg, Vienna 1990, ISBN 3-486-55381-X , p. 202-228 .

- Hannelore Schröder (Ed.): Olympe de Gouges - man and citizen . One-subject, Aachen 1995, ISBN 3-928089-08-0 .

Web links

- Facsimile of the original version of the Declaration of the droits de la femme et de la citoyenne at Gallica

- The rights of women , German translation by Viktoria Frysak

- The rights of women , German translation by Gisela Bock from 2009

- Manfred Geier : Gouges, Olympe de . In: Kurt Groenewold , Alexander Ignor, Arnd Koch (eds.): Lexicon of Political Criminal Trials , Online, as of July 2017.

Individual evidence

- ^ Translation from: Karl Heinz Burmeister: Olympe de Gouges. The rights of women 1791. Stämpfli Verlag, Bern 1999