Rudolf Breitscheid

Rudolf Breitscheid (born November 2, 1874 in Cologne ; † August 24, 1944 in Buchenwald concentration camp ) was an initially left-liberal and later a social democratic politician .

Life

Rudolf Breitscheid was born as the son of bookstore assistant Wilhelm Breitscheid and his wife Wilhelmine, geb. Thorwesten, born. He attended the Friedrich Wilhelm High School in Cologne.

Since 1908 he was with the feminist and suffragette Tony Breitscheid , geb. Drevermann (1878–1968) married.

Education

From 1894 to 1898 he studied political economy at the University of Munich and the University of Marburg . Karl Rathgen was one of his academic teachers . In Marburg he became a member of the Arminia Marburg fraternity . After successfully defending his doctoral thesis submitted in 1898 on "The land policy in the Australian colonies" he became a doctor doctorate and worked 1898-1905 as an editor and correspondent bourgeois and liberal newspapers.

Political career

From 1903 to 1908 Breitscheid was a member of the liberal Radical Association . In 1904 Breitscheid was elected to the Berlin city council and also to the Brandenburg provincial parliament. Because he did not agree with the new party's strategy by participating in the Bülow Block , he resigned from the Liberal Association in 1908 and became a founding member of the left-liberal Democratic Association (DV). Until the Reichstag election in 1912 he was its chairman.

After the DV failed in this election, he joined the SPD . From May 1915 he published the press correspondence Socialist Foreign Policy , which criticized the peace policy of the SPD leadership. Finally, in 1917, he switched to the newly formed USPD . Here he published the organ Der Sozialist from November 1918 until it was discontinued in September 1922.

From 1918 to 1919 he was the Prussian Minister of the Interior . For the USPD he sat in the Reichstag from 1920 . In October 1922 Breitscheid returned to the SPD with the merger of the USPD and MSPD . He was the chairman and foreign policy spokesman for the SPD parliamentary group in the Reichstag, and in this role also advocated the western orientation of the Reich in line with the party line. He later became a member of the German delegation to the League of Nations . He was a member of the Presidium of the Pro Palestine Committee .

In the last years of the Weimar Republic, as a prominent Social Democrat responsible for foreign policy, he became an object of abuse for the right-wing radical press. He clearly foresaw the consequences of a Hitler dictatorship:

- “We have to pose the question: what would the victory of Hitlerism mean in the presidential election? The first answer - I think you agree with me - is the overthrow of the Weimar Constitution. Certainly, I admit that the soil of democracy is now narrowed by the system of emergency ordinances, which we really did not have the occasion to bring about. But the terrain is still there, the constitutional terrain, this terrain, this soil can be cleared again, the barbed wires of the emergency ordinances can be removed. If Hitlerism comes to power, the foundation on which we can build the house of our future and the house of our children will be removed. "

In the same speech Breitscheid differentiates himself from the communists:

- “You are proposing that all private debt obligations to capitalist foreign countries be canceled. The capitalists, big banks and big businessmen, will be ready to give you an address of thanks. They protect themselves in front of the capitalist debtors who have carelessly, carelessly borrowed money that they do not want to repay. The Communist Party comes and with the stroke of a pen erases the debt of the capitalists. I have to say: we have never seen greater self-sacrifice in the Communist Party either. "

In the weeks after the decision of the enabling law in 1933, he and Otto Wels by Konstantin von Neurath also cited as examples that reports were only slander in the foreign press about Nazi terror against dissenters.

exile

After the takeover of the Nazis , the couple emigrated Breitscheid in March 1933 via Switzerland to France. Rudolf Breitscheid's name was on the first expatriation list of the German Reich in August 1933 . In exile in Paris he was a co-initiator of the Lutetia circle (1935 to 1936). It was an attempt to form a popular front against the Hitler dictatorship. Breitscheid was one of the signatories of the " Appeal to the German People ". The University of Marburg revoked his doctorate on March 10, 1938 .

Arrest and death

When the German Wehrmacht reached Paris in 1940, Breitscheid fled to Marseille . After he was assigned Arles as a forced residence by the French authorities during the German occupation in the autumn of 1940 , he was betrayed there, like Rudolf Hilferding, by French supporters of the Vichy regime , arrested, taken to Vichy and handed over to the Gestapo . Breitscheid came from the La Santé prison in Paris to the Gestapo prison on Prinz-Albrecht-Strasse in Berlin. At the beginning of January 1942 he and his wife were taken to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp , and in autumn 1943 the couple was taken to a special barracks in the Buchenwald concentration camp in the Fichtenhain special camp , which was outside the actual concentration camp area. On August 24, 1944, a heavy American air raid on Buchenwald took place. His wife Tony Breitscheid, who was buried in the splinter trench, was rescued seriously injured. As fellow prisoners reported, Rudolf Breitscheid was also buried and found dead. At the same time, the death of Ernst Thälmann was announced, who did not - as the Nazi media claimed - died in the air raid, but had been shot six days earlier.

It is occasionally alleged that Breitscheid was killed by an SS guard shot through the heart; however, there is no reliable source for this.

Commemoration

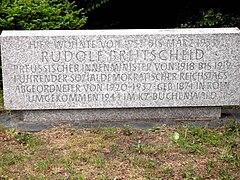

Rudolf Breitscheid's grave is in the south-west cemetery Stahnsdorf near Berlin. It is dedicated to the city of Berlin as an honorary grave . His name is written on a memorial plaque in the central roundabout of the Berlin Socialist Memorial .

In Berlin , Breitscheidplatz in the western center is named after him. In numerous cities and especially in many East German municipalities, streets bear his name (e.g. Rudolf-Breitscheid-Straße in Cottbus ). In Marburg , too , where he began his academic career, a street on the site of the former Tannenberg barracks was named after him.

In the period from 1964 to 1988, a cargo ship belonging to the Deutsche Seereederei Rostock (DSR), the state shipping company of the German Democratic Republic, was named after Rudolf Breitscheid.

Several polytechnic high schools were given the name Rudolf Breitscheid , so u. a. in Görlitz .

Since 1992, one of the 96 memorial plaques for members of the Reichstag murdered by the National Socialists has been commemorating Breitscheid in the Berlin district of Tiergarten on the corner of Scheidemannstrasse and Platz der Republik .

Fonts

- Land Policy in the Australian Colonies . New stock exchange hall, Hamburg 1899.

- The Bülow Block and Liberalism . Reinhardt, Munich 1908.

- Personal regiment and constitutional guarantees . Ehbock, Berlin 1909.

- Everything is ready! Speech in the party committee of the Social Democratic Party of Germany on January 31, 1933 . R. Hauschildt, Berlin 1933.

- Reichstag speeches . Edited by Gerhard Zwoch. AZ Studio publishing house, Bonn 1974.

- Anti-fascist contributions 1933–1939 . Edited by Dieter Lange. Verlag Marxistische Blätter, Frankfurt am Main 1977, ISBN 3-88012-450-7 .

- “The main task of the left is criticism.” Journalism 1908–1912 . Edited by Sven Crefeld. edition Rubrin, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-00-050066-4 .

literature

- Rainer Behring: Rudolf Breitscheid (1874–1944). Liberal social reformer - verbal radical socialist - social democratic parliamentarian . In: Detlef Lehnert (ed.): From left liberalism to social democracy. Political life in historical conflicts of direction 1890–1945. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne Weimar Vienna 2015, ISBN 978-3-412-22387-8 , pp. 93-124.

- Marie-Dominique Cavaillé: Rudolf Breitscheid et la France 1919-1933. Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1995, ISBN 978-3-631-48795-2 .

- Helge Dvorak: Biographical Lexicon of the German Burschenschaft. Volume I: Politicians. Sub-Volume 1: A-E. Winter, Heidelberg 1996, ISBN 3-8253-0339-X , p. 134.

- Detlef Lehnert: Rudolf Breitscheid (1874–1944). From left-wing journalist to social democratic parliamentarian. In: Peter Lösche, Michael Scholing, Franz Walter (Eds.): Preserve from forgetting. Life paths of Weimar Social Democrats . Colloquium Verlag, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-7678-0741-6 , pp. 38-56.

- Paul Mayer: Breitscheid, Rudolf. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , p. 579 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Peter Pistorius: Rudolf Breitscheid 1874–1944. A biographical contribution to the history of German political parties . Dissertation, University of Cologne 1970.

- Wilhelm Heinz Schröder : Social Democratic Parliamentarians in the German Reich and Landtag 1867-1933. Biographies, chronicles, election documentation. A handbook (= handbooks on the history of parliamentarism and political parties. Volume 7). Droste, Düsseldorf 1995, ISBN 3-7700-5192-0 , short version online as a biography of Rudolf Breitscheid . In: Wilhelm H. Schröder : Social Democratic Parliamentarians in the German Reich and Landtag 1876–1933 (BIOSOP) .

- Martin Schumacher (Hrsg.): MdR The Reichstag members of the Weimar Republic in the time of National Socialism. Political persecution, emigration and expatriation, 1933–1945. A biographical documentation . 3rd, considerably expanded and revised edition. Droste, Düsseldorf 1994, ISBN 3-7700-5183-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Rudolf Breitscheid in the catalog of the German National Library

- Newspaper article about Rudolf Breitscheid in the 20th century press kit of the ZBW - Leibniz Information Center for Economics .

- Gabriel Eikenberg: Rudolf Breitscheid. Tabular curriculum vitae in the LeMO ( DHM and HdG ), there also the audio document: Address for the SPD on the Reichstag election on September 14, 1930 .

- Rudolf Breitscheid in the database of members of the Reichstag

- Rudolf Breitscheid in the online version of the Reich Chancellery Edition Files. Weimar Republic

- Short biography from the archive of social democracy

- Siegfried Heimann : Tony Breitscheid. About Tony Breitscheid's fate after the end of the war and how Rudolf Breitscheid's grave was dealt with . In: Our story . Information from the SPD Berlin from November 1999, requested on August 14, 2020.

- Rudolf Breitscheid's biography . In: Wilhelm H. Schröder : Database Social Democratic Members of the Reichstag and Reichstag candidates 1898-1918 (BIOKAND)

- Rudolf Breitscheid's biography . In: Heinrich Best and Wilhelm H. Schröder : Database of Members of the National Assembly and the German Reichstag 1919–1933 (Biorab – Weimar)

Individual evidence

- ^ Rudolf Breitscheid: The land policy in the Australian colony . Neue Börsen-Halle, Hamburg 1899, p. 83 (biographical information of the author at the end of the dissertation).

- ↑ a b History: A street in Wandlitz. Breitscheidstrasse. In: Heidekraut Journal from August / September 2010; P. 8

- ↑ Breitscheid's speech in the Reichstag on February 24, 1932. The National Socialists left the room a little later - as was not uncommon back then - in protest.

- ↑ Here Breitscheid specifically addressed the MP of the Communist Party, Ernst Torgler .

- ↑ Sees Rebirth of War Time Propaganda , Berlin March 26, 1933. St. Joseph Gazette, St. Joseph, Missouri, March 27, 1933.

- ↑ Michael Hepp (ed.): The expatriation of German citizens 1933-45 according to the lists published in the Reichsanzeiger, Volume 1: Lists in chronological order . De Gruyter, Munich 1985, ISBN 978-3-11-095062-5 , p. 3 (Reprint 2010).

- ^ Hans Georg Lehmann: National Socialist and Academic Expatriation in Exile. Why Rudolf Breitscheid was stripped of his doctorate . University of Marburg 1985, ISBN 3-923014-09-0 .

- ↑ Helma Brunck: The German Burschenschaft in the Weimar Republic and in National Socialism . Universitas Verlag (1999), ISBN 978-3-8004-1380-5 , p. 400

- ↑ chroniknet

- ^ Biographical data from Tony Breitscheid

- ^ Rudolf Breitscheid on the website of the Oberschule Innenstadt in Görlitz

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Breitscheid, Rudolf |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German politician (DV, SPD, USPD), MdR |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 2, 1874 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Cologne |

| DATE OF DEATH | August 24, 1944 |

| Place of death | Buchenwald concentration camp |