Mark Brandenburg

|

Territory in the Holy Roman Empire |

|

|---|---|

| Mark Brandenburg | |

| coat of arms | |

| map | |

| Map of the Mark Brandenburg in the Holy Roman Empire, 1618 | |

| Alternative names | Margraviate of Brandenburg, Electorate of Brandenburg |

| Arose from | Nordmark |

| Form of rule | Margraviate |

|

Ruler / government |

Margrave, Elector |

| Today's region / s | DE-BB , DE-BE , DE-MV , DE-ST , PL-LB , PL-ZP |

| Parliament | Electoral College , Imperial Prince Council |

| Reichskreis | Upper Saxon |

|

Capitals / residences |

the Brandenburg , in Neustadt Brandenburg , Tangermünde Castle (around 1400), Berlin City Palace (from the middle of the 15th century) |

| Dynasties |

Ascanians , Wittelsbachers , Luxembourgers , Hohenzollerns |

|

Denomination / Religions |

Roman Catholic until 1539, then Protestant ( Lutheran , from 1613 also Calvinist ) |

| Language / n | Low German , West Slavic languages (including Polish , Lower Sorbian ) |

| currency | Brandenburg pfennig and groschen |

| Incorporated into | Brandenburg Province |

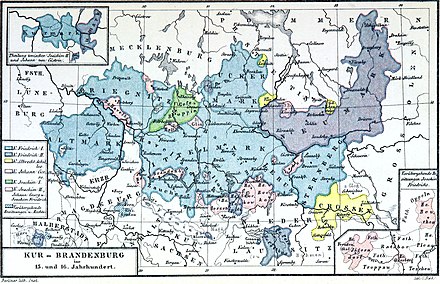

The Mark Brandenburg was a territory in the Holy Roman Empire . It originated from the former Nordmark . June 11, 1157 went down in history as the founding date. Due to the development to the electorate of Brandenburg since the end of the 12th century, it played a prominent role in German history. The Golden Bull of 1356 confirmed the vote of the Margraves of Brandenburg as elector in the royal election. The margraviate of Brandenburg comprised the Altmark (west of the Elbe ), the central region (between the Elbe and Oder ), the Neumark (east of the Oder), parts of Niederlausitz and scattered territories.

From 1618 the Electors of Brandenburg also ruled the Duchy of Prussia in personal union , a phase that is summarized under the term Brandenburg-Prussia . In the 18th century, after the coronation of Frederick III. of Brandenburg from the territories of the Prussian kings, the monarchy Prussia as a new European state. With this the margravate was effectively transformed into a province of Prussia. The province of Brandenburg was formally founded in 1815 after the reorganization of Prussia by the Congress of Vienna .

The colloquial synonymous use of the term Mark Brandenburg or short as Mark for today's state of Brandenburg is neither historically nor territorially correct. While former Brandenburg areas are now in Saxony-Anhalt , Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and the Polish voivodeships of Zachodniopomorskie and Lubuskie , areas in the south of today's state never, partially or even briefly, belonged to the market. Brandenburg and Berlin separated in several stages between 1875 and 1936.

geography

| position | landscape | (historical) square miles (before 1811) |

km² |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Altmark | 82 | 4,510 |

| 2 | Mittelmark | 250 | 13,750 |

| 3 | Uckermark | 68 | 3,740 |

| 4th | Prignitz | 61 | 3,355 |

| Sum 1-4 | Kurmark | 461 | 25,355 |

| 5 | Neumark | 220 | 12,100 |

| Sum 1-5 | Mark Brandenburg | 681 | 37,455 |

The Mark Brandenburg was in the north of Central Europe . Neither the low local plateaus and hilly lands nor the rivers Elbe and Oder stood in the way of the margraves' sovereignty . The construction began in the Ascanian ancestral lands (later called Altmark ). They worked their way eastwards by peaceful and warlike means. Therefore, in contrast to the state of Brandenburg , the Mark was stretched in a west-east direction and compressed in a north-south direction. There were over 400 kilometers between Salzwedel in the west and Schivelbein in the east. After the acquisition of the Mark Lausitz (later Lower Lusatia , 1302/1304) and the states of Budissin and Görlitz (later Upper Lusatia without the southern part, after 1233), the largest expansion was achieved. The Lusatian highlands in the south and the Baltic Sea in the north (half of Wolgast , from 1230 to 1250) only served as geographic barriers at times. The marrow was unable to develop firm, permanent natural boundaries. After the end of the Askanian period , the territory shrank again.

With an area of 37,455 km², the Mark Brandenburg has been one of the largest territories of the Holy Roman Empire in quantitative terms since the 16th century, comparable to the Electorate of Saxony , which had an area of around 35,000 km² and larger than the Duchy of Bavaria in 1801 with 590 square miles (32,450 km²), which, however, had lost the Innviertel in 1778, as well as somewhat smaller than the Kurhannover, which was enlarged in 1741 with 700 square miles (38,500 km²).

External relations

Despite its socially and economically very weak starting position in the empire, Brandenburg developed into an important princely state, which from the 17th century developed tendencies towards a great power policy, which intensified with the increasing size of the dynastically connected Hohenzollern states . The states that suffered from this territorial expansion were, above all, the Brandenburg neighbors in all directions.

In its external relations, the Mark maintained very close contacts with the southern Electoral Saxony . Overall, Saxony has been the most important partner and rival for Brandenburg since the Middle Ages (until today).

Pomerania in the north, ruled by a Slavic dynasty, was a neighbor with which Brandenburg was almost constantly in armed conflict in the Middle Ages and which Brandenburg tried unsuccessfully to keep outside the imperial union. To Mecklenburg relations were marked rather low, in part because it another since the 16th century Circle belonged as Brandenburg and a more maritime focus had, in contrast to the more dominant inland orientation of Brandenburg, which are oriented in all directions needed. There were stronger ties with Anhalt , especially through the Ascanian dynasty, which continued into the early modern period (e.g. the old Dessauer ). In the area of the Middle Elbe, the Archdiocese of Magdeburg , Brandenburg and Saxony struggled for supremacy for a long time, until Brandenburg finally succeeded in asserting itself there. Due to the great importance of waterways for long-distance trade, the Elbe was very important for Brandenburg's foreign trade. Most of the exports and imports were made via Hamburg and customs cleared at the customs post in Lenzen . Szczecin in Pomerania was an important pick-up point for goods shipped on the Oder . Goods could be sold and acquired at the Leipzig Trade Fair , which were then transported north to Berlin via Reichsstrasse . After Silesia , at least in the 18th century, there were still many trade barriers and tariffs in force that blocked a closer exchange relationship. Relations with the eastern neighbor, the great power Poland , were mainly based on the question of the relationship to the Duchy of Prussia in the 17th century and in the Middle Ages during the Ascanians and Piasts to enforce mutual expansion efforts east of the Oder. The gateway for the Poles was Frankfurt (Oder) , its trade fair and university. Especially at the beginning of the Mark, Lüneburg and Braunschweig were relevant, as many settlers and treks came to Brandenburg from there.

Settlement structures

Cartographic overview

| year | resident | Population density per km² |

|---|---|---|

| 1701 | 283,566 | 11.72 |

| 1713 | 319,566 | 13.20 |

| 1725 | 367,566 | 15.19 |

| 1740 | 475.991 | 19.67 |

| 1755 | 586.375 | 24.23 |

| 1763 | 519,531 | 21.47 |

| 1786 | 683.145 | 28.23 |

| 1800 | 824,806 | 34.08 |

Demographic and settlement history

The settlement of Brandenburg was shaped by the medieval colonization of the east that took place in Brandenburg from the 12th to the 14th centuries. The settlement took place from the Ascanian western areas west of the Elbe in the Altmark gradually over 400 kilometers to the east. The settlement belt was compressed in a north-south direction and stretched in an east-west direction. The actual settlement center of the Mark runs along the Havel with the chain of cities Brandenburg an der Havel - Potsdam - Berlin - Frankfurt (Oder).

| year | 1320 | 1486 | 1564 | 1617 | 1634 | 1690 | 1750 | 1800 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| resident | 200,000 | 308,750 | 381,000 | 418,666 | 300,000 | 413,516 | 767.354 | 1,124,806 |

From the Middle Ages to the beginning of the Thirty Years War, the population doubled from around 200,000 to a little over 400,000 in the approximately 37,500 km² area of the Mark Brandenburg. The population growth was accordingly unsteady and weak. Frequent wars, epidemics and famines led to slumps in the population and increased mortality. The population density of Brandenburg was at all times significantly lower than the overall average of the Holy Roman Empire. The Thirty Years' War caused a considerable decline in the population in Brandenburg, which was not evened out again until the end of the 17th century. After that, a strong population growth set in in the first half of the 18th century, which expanded from then on.

| landscape | Altmark | Prignitz | Mittelmark | Uckermark | Neumark | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhabitants 1750 | 80.114 | 65,635 | 336.250 | 66,355 | 219,000 | 767.354 |

| Inhabitants 1801 | 110.188 | 78,499 | 538.095 | 101.148 | 300,000 | 1,127,930 |

| Percentage of the population 1750 | 10 | 9 | 44 | 9 | 29 | 100 |

| Percentage of the population 1800 | 10 | 7th | 48 | 9 | 27 | 100 |

| Population density per km² 1800 | 24.43 | 23.40 | 39.13 | 27.04 | 24.79 | 30.11 |

In relation to the five regions of the Mark, the population of the Mittelmark predominates in quantitative terms, with Berlin as its largest metropolitan area. The Mittelmark was also the most densely populated area of the Mark, while the other four parts of the country are demographically classified as peripheral areas.

In 1778, 42 percent of the Kurmark population consisted of urban residents, half of which came from Berlin. The very high urban proportion of the population is put into perspective, since most of the Brandenburg cities were very small and the largest villages were larger than the smallest cities. In 1750 there were 1900 villages and spots in the Kurmark. The population of the rural population is said to have been 221,000 in 1725 and 440,000 in 1800. In 1800, 334,185 civilians and 57,129 members of the army lived in the towns of the Kurmark, a total of 391,314 people. Of these, 172,132 people lived in Berlin alone, almost 44 percent of the urban population of the Kurmark. The average population of the remaining 64 Kurmark cities of the remaining total urban population of 219,182 inhabitants is 3424 inhabitants per city. This shows the great importance of Berlin for the Kurmark as a whole. All cities remained subordinate in comparison to Berlin and the Margraviate of Brandenburg as a whole formed an urban monocenter in the heart of its territory, which tied the majority of the resources and funds to itself, while the wider area belonged to the periphery.

The total population of the Kurmark was 1,824,806 people. On average, the population increased by 5075 people per year in the 1790s. The Kurmark with Altmark, Uckermark, Prignitz and Mittelmark covered an area of 432-434 square miles from 1700 to 1804. Converted to square kilometers with a ratio of 1:56, this results in an area of 24,201 square kilometers.

| country | Mark Brandenburg |

"Westphalia" | Electoral Saxony | Hanover | Denmark | "Schleswig- Holstein" |

Württemberg | Bohemia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EW / km² | 30th | 42 | 50 or 60 | 28 | 20.5 | 32.8 | 70.6 | 57 |

The population of the Neumark was 1700: 120,000 inhabitants, 1754: 219,000 inhabitants, 1800: 300,000 inhabitants. The entire Mark Brandenburg had 1,124,806 inhabitants in 1800 on a total area of 37,455 km², which results in a population density of 30 inhabitants per square kilometer. In comparison, the southern neighbor, Kursachsen , had a population of almost two million inhabitants with a state area of 34,000 km² and therefore a population density of almost 60 inhabitants per square kilometer and was therefore twice as densely populated. The 29,300 km² area of Westphalia reached a population of 1,230,000 inhabitants in 1800 and therefore had a slightly higher population density of 42 inhabitants per km².

| Part of the country | Mark Brandenburg |

East Prussia |

West Prussia |

Silesia | Pomerania | Duchy of Magdeburg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| resident | 1,124,806 | 931,000 | 545,000 | 2,000,000 | 500,000 | 309,000 |

In relation to the other Prussian parts of the country, the Margraviate of Brandenburg was the second largest province after Silesia in terms of the absolute number of inhabitants (see table above).

According to this, the Margraviate of Brandenburg was a rather sparsely populated area in Germany, although it was comparatively densely populated in comparison to more northern or eastern states.

Rural area

The country was separated from the city by legal regulations governing administration, jurisdiction and the tax system. It is the living area of the nobility and peasant class, of members of the domain, order administration and the village churches.

There were two basic rulership conditions in the country: on the one hand, for a quarter of all villages the manorial estates, on the other hand for a good eighth the domain villages administered by offices. About a tenth were municipal treasury villages , the rest was accounted for by the commander and offices of the Order of St. John and villages in civil ownership, monasteries, other foundations and universities. Both forms of rule could occur in a village at the same time.

In addition to the few rounds and clustered villages , the street and anger villages are typical of Brandenburg as a planned settlement in the Brandenburg region . These were preferably built on plateaus. Among the settlements that have broken up in Berlin alone, there are 31 village villages and 13 street villages. Two-thirds of the villages had manors that later became estates further developed. In the so-called church villages there are often field stone churches from the Wilhelminian era .

Cities

In the Middle Ages and in the early modern period, the Margraviate of Brandenburg did not have a dense urban landscape like its southern neighbor, the Electorate of Saxony . The first cities were founded in 1160. Most of the 100 or so cities in the state of Brandenburg were built in the 12th and 13th centuries. In addition to the building of castles and monasteries, the founding of towns played an important role in the reclamation of the newly acquired areas and the expansion of Ascanian sovereignty. The starting point for the founding of cities were mostly Slavic villages, fishermen and castle settlements. Only a few cities emerged freely and without an existing settlement structure. The construction of new settlement centers and the privileging of existing ones took place according to territorial planning aspects, for example along a systematic road network. The administrative basis of the new municipalities was the Magdeburg city law , from which the Brandenburg city law , which was later applied to most cities, was derived. In Brandenburg there was the type of media city , which was subordinate to its own landlord, and the larger immediate cities , which were directly subject to the sovereign.

City councils were formed in the largest cities in the 13th century and functioned as a self-governing body for the city's citizens, with the upper commercial class dominating. This has been documented for Stendal in the Altmark since 1215, for Brandenburg an der Havel since 1263 and for Spandau since 1282. In addition to these three cities, Prenzlau as the trading town and Berlin-Cölln were two further urban centers in Brandenburg from 1261 onwards, the royal seat of the Askanian margraves . External dangers such as war and robber barons, the power imbalance between guilds and patriciariats who were able to advise them , which repeatedly led to inner-city conflicts, plague epidemics and fires characterized the Brandenburg urban development in the Middle Ages. In 1308, the Brandenburg cities of Stendal, Spandau, Cölln , Berlin and Frankfurt (Oder) joined forces to form the Märkisches Städtebund . Until 1438 the cities of Brandenburg allied themselves again and again in different compositions. The Hanseatic League had members in Brandenburg, but they were not very influential in the federal government. In the 14th century the cities experienced their first economic and political climax. In the course of the interregnum after 1319, the cities succeeded in loosening the influence of national rule. The cities received extensive political rights from the sovereign. These included the tax authority over services provided by the citizens, the right to tax permits, the high level of jurisdiction and the right of alliances. The representative fortifications, stately town halls and churches that are still visible in many places, which were built at this time, bear witness to the civil autonomy and cultural prosperity of the Brandenburg cities. There is no reliable information about the population of Brandenburg cities in the Middle Ages, as there are no suitable records such as tax lists or the like. A hardly verifiable estimate, for example, assumes that the town of Salzwedel in the Altmark had 6,800 inhabitants before the Thirty Years' War. Other large Brandenburg cities of this time were Stendal and Frankfurt (Oder) with around 7,000 inhabitants. Frankfurt (Oder) became a humanistic center during the Reformation when the Brandenburg University Viadrina was founded in 1506 .

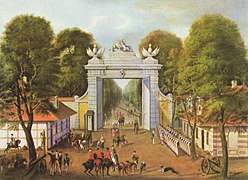

- Views of Brandenburg cities

Berlin around 1730, Friedrich Bernhard Werner (1690–1776)

Dismar Degen - Potsdam, Jägertor

Dismar Degen : Construction of Friedrichstadt in 1735

View of Potsdam from the Brauhausberg , 1772

Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff : View of Rheinsberg , 1737

from 1750 to 1800

The largest cities formed long-distance trading centers and enabled them to take up a politically important position in competition with the landed gentry , the church and the sovereign . Since the 15th century, the politically relatively independent position of the cities weakened again due to the pressure of the Hohenzollern electors and political powers were again limited. The reason for this was the breaking of Berlin's indignation in 1447/1448, which ushered in the end of urban self-autonomy. Council autonomy was increasingly restricted in the 17th century in favor of central princely rule. The Thirty Years' War led to a drastic decline in the number of inhabitants in the cities.

1625, just before the war-related population declines were in Brandenburg following by region divided cities: in the Neumark had 36 settlements received the municipal law (see. List of cities Neumark ) in the Altmark there were 10 cities in Prignitz There were 13 cities, in the Ruppiner Land five places had city rights, the Cottbuser Kreis had two urban settlements, the Uckermark had 11 cities and the remaining Mittelmark with Havelland, Zauche , Teltow , Land Lebus , Barnim and Oderbruch 39 cities. At that time, the Margraviate of Brandenburg consisted of 117 cities. Of these, 28 cities had more than 1500 inhabitants and only a few more than 4000 inhabitants. 32 cities had fewer than 500 inhabitants.

| year | <500 inhabitants | 500–1499 inhabitants | 1500–3999 inhabitants | > 4000 inhabitants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1625 | 32 | 57 | 24 | 4th |

| 1750 | 5 | 65 | 38 | 9 |

| 1800 | 4th | 44 | 69 | 18th |

The effects of the Thirty Years' War on the cities, such as the destruction of the war, population decline and economic stagnation, were only completely overcome in the course of the 18th century. For a long time, deserted houses were to be found in the cityscapes. In the 18th century, the size of the city increased again significantly. The median city had 1750 1204 inhabitants and 1800 1727 inhabitants. If Berlin is excluded from the list as an extraordinary influence, the remaining 116 Brandenburg cities had an average size of 1750: 1684 inhabitants and 1800: 2546 inhabitants.

The constitutional and administrative integration of the cities into the expansive princely central state, which was promoted from 1650 to 1750, took place even in smaller cities through the establishment of garrisons , the supervision of police violence, financial administration, jurisdiction, medical affairs and, above all, with the introduction of excises , their receipt and Supervision was carried out by government officials deployed in the cities. This process of enclosing the former autonomous cities in the state brought about an expansion of the social structure in the middle and upper areas of society in the cities through the establishment of central state institutions. In 1719 a Kurmärkische town order was enacted. This reorganized the local self-government . Despite the sovereign claim to omnipotence, Gravamina of the Brandenburg cities came about under the leadership of Brandenburg an der Havel against the presumption of competence of state officials in urban matters. The Brandenburg cities did not bow without contradiction to the absolutist claim to power and developed a perseverance that prevented the city citizens from becoming unfree subjects.

The cities stagnated economically at the beginning of the 18th century. Problematic for the development of the Brandenburg cities was the fact that their own sales market for local products was too small. There was a lack of affluent buyers, so that trade remained localized. The only relevant exception was Berlin , where towards the end of the 17th century, initiated by the Berliner Hof , a more developed demand market for certain contemporary products in the luxury segment had developed. This led to a strong population growth of Berlin from 1685 to 1711 from around 18,000 to 55,000 inhabitants and by 1719 already 64,000 inhabitants. With this, Berlin overtook all other cities in Brandenburg. Between 1564 and 1590, Spandau was developed into the most important fortress town in the Brandenburg region under the direction of Rochus zu Lynar . Since the 16th century, the former Brandenburg capital of Brandenburg an der Havel, which had the highest court of law ( appellate authority ), lost its former top position. The warehouse in Frankfurt (Oder) lost its central position in the Oder trade to Stettin . The fair in Frankfurt an der Oder could not prevail nationally against the Leipzig fair. Potsdam developed into the second political and cultural center of Brandenburg since the 17th century. In 1740 around 11,700 civil and military people lived here. Frankfurt (Oder) and Stendal had permanently lost their importance and after the burglaries in the first half of the 17th century no longer achieved their original importance.

Because of the widespread manorial rule in Brandenburg since the 17th century, only a few workers were made redundant. Since otherwise there was no significant supra-local trade in Brandenburg, the purchasing power of the artisanal urban population in the smaller towns remained low, which hampered urban development. Although the cities developed into administrative centers, most cities remained smaller than elsewhere and developed an economic structure that corresponded to that of villages. The economy was dominated by agriculture and the type of town called arable town ( e.g. Rathenow , Angermünde , Königsberg , Kremmen ) became the most widespread type of town in Brandenburg. Such cities, especially if they were left without a city wall, often did not make an urban impression. The arable farmers tilled their fields in the vicinity of their town in a very similar way to the farmers around their villages. A bourgeoisie in the cities that would have developed into a leading political force was hardly developed due to the poorly differentiated economic structure of the Brandenburg cities. With the exception of Berlin and the surrounding area, the cities saw themselves as the center of a rural environment and not as a formative political force like the Free Imperial Cities at the same time .

story

Creation of the Mark Brandenburg

The Slavs in the Elbe area

In the course of the migrations , the Suebi , the Elbe-Germanic branch of the Semnones , left their home on the Havel and Spree in the direction of Upper Rhine and Swabia from the 5th century onwards, with the exception of a few remaining groups . In the late 6th and 7th centuries, Slavs moved into the presumably largely deserted area . The Wilzen tribe , later called Liutitzen , settled in the area of the later Mark Brandenburg . The Abodrites settled in the north and the Sorbs in the south .

The main tribe of the Wilzen-Liutitzen probably had no monarchical or oligarchical leadership for the entire area. The small tribes (including the Heveller, Sprewanen and Zamzizi ) lived under the leadership of long-established families. The focal points were larger wood-earth castles, such as the Brandenburg an der Havel, Spandau, Köpenick or Altfriesack , to which a territory was assigned in the vicinity. The boundaries were drawn based on the course of the river and water. Town-like large settlements like those that existed under the Piasts in Poland at the same time do not seem to have existed. The Slavs seem to have preferred small streets, dead ends and round lanes as a form of settlement . Its trade and industry developed in many ways due to its proximity to the East Franconian Empire and the long-distance trade route from Magdeburg via Spandau to Gnesen . There is evidence of the cultivation of millet and oats, as well as animal husbandry and the use of water (fishing) and forests (hunting, berries, honey, building materials). There were craft workshops in the larger settlements. In addition to the ceramists and the blacksmiths responsible for the weapons and fishing tackle, there were also comb makers and textile workers. There was no writing activity. They minted coins in the form of bracteates . There were no stone buildings. The worship of old Slavic deities like Triglaw died out in the 12th century as a result of Christianization.

The Sprewanen settled east of the Havel and Nuthe , in what is now Barnim and East Teltow . Their main castle was at the confluence of the Dahme and Spree rivers in Köpenick . To the west of the two rivers (in Havelland and Zauche ) lived the Hevellers . The main castle of the Stodorans, as it is called, was the Brandenburg . Up the Havel were two more fortifications not far from each other - the important Spandau castle wall and a small complex on the site of today's Spandau Citadel . The two Elbe Slavic tribes had to defend themselves against the powerful feudal states from the west. Occasionally they waged disputes among themselves and with neighboring Slavic tribes, often in a warlike manner.

First eastward expansion, first brands

After the successful campaigns against the Saxons in 804 , Charlemagne briefly left part of the Saxon land between the Elbe and the Baltic Sea to the Abodrites, allied with him, with Northern Albingia . A relatively quiet period lasted up to the year 928. In the following so-called first phase of the German East Settlement , King Heinrich I conquered Brandenburg in the winter of 928/929 . The tribes as far as the Oder were subject to tribute . Under Otto I , Marken , German border regions in the Slavic region, followed in 936 . From around 965 (the dating is controversial among historians) he established the dioceses of Brandenburg and Havelberg . German rule contented itself with occupying existing castles to collect tributes and building diocese churches. German farmers have not yet settled. The parishes of the dioceses were therefore very small. The daily celebration of the mass was considered to be evidence of the rule of Christ in the Slavic land.

After Gero's death , the Saxon Ostmark was divided into five smaller brands: the Nordmark , which later became the Mark Brandenburg, and south of it into four other brands, especially in the Lausitz region . In the Slavic Uprising of 983 , many Slavic tribes allied and threw the Germans back again. The dioceses of Brandenburg and Havelberg were destroyed. For around 150 years, until the Liutizenbund collapsed in the middle of the 11th century, German expansion stood still.

Crusades and approach of the Heveller prince Pribislaw-Heinrich to the empire

In the beginning of the High Middle Ages , the increase in population and the inheritance regulations led to tensions in the old empire, for the relaxation and sewerage of which the “unneeded excess population” was “relocated” to the east by the imperial elite. The flow of movement was described in the 19th century with the programmatic battle term urge to the east . The direction of imperial politics could for a time be determined by the old Saxon dukes, who concentrated the corresponding political power on themselves. As a result, a sustained north-east orientation developed in the empire in the first half of the 12th century, which led to a regrouping movement of resources and attention of the elites to the east, as a result of which the empire extended its eastern border by several hundred kilometers to the east could relocate and a corresponding population movement on a larger scale from west to east began.

Towards the end of the 11th century, the situation for the Saxons on the Slavic border improved, initially in the north. The Obodriten prince Heinrich von Alt-Lübeck won the rule over the Wagrier and was able to subdue a large part of the west Slavic area with Saxon support. Poland, which became weaker under the successors after Boleslaw's death in 1025, also gained strength again. Denmark also put increasing pressure on the frequent raids by Slavic ships on its coasts. In addition to the self-weakening of the Lutizenbund , these external factors contributed to the beginning of the decline of Elbe Slavic independence. If it was previously the German royal power who advanced the eastward expansion course, the East Saxon princes now came to the fore. You and your other counterparts in the empire consistently pushed ahead with the expansion of sovereignty within your territory. In order to increase their own chances against competitors in the empire in the process of expanding the internal structure of rule in the empire, the princes of East Saxony tried to expand their rule out of Elbe Slavic territory. Their territories continued to be claimed by the empire and had not yet been Christianized .

From around 1100 the Magdeburg archbishops and East Saxon princes began again to invade the Slavic territories. The dukes of Saxony acted as margraves of Billunger Mark, the counts of Stade as margraves of Nordmark and the Wettins as margraves of Lausitz and Meißen. Count Otto von Ballenstedt , whose property lay mainly between the Eastern Harz and the mouth of the Mulde , was one of them. He came from the family mentioned for the first time with his grandfather Esico in 1036, which is probably called "Askanier" after the old Askania castle near Aschersleben , and "Anhaltiner" after the Anhalt castle in the Harz region , which first appeared in 1140 . Otto's name stands under the widespread letter with which East Saxon princes and bishops called in 1108 to fight against East Elbe paganism based on the example of the crusade to the Holy Land that began in 1096 . Around 1110 Otto von Ballenstedt increased his influence from Bernburg in the direction of the Heveller border near Görzke in Fläming . In 1115 Otto von Ballenstedt defeated an army from Wenden near Köthen that had crossed the Elbe. Otto used the victory to cross the Elbe and to occupy the area around Roßlau, Coswig, Lindau, Belzig up to the Zauche. The area was called Zerbstgau and remained in the possession of the Anhaltinian people. This acquisition of territory in the East Elbe Slavic country made the Anhaltines neighbors of the Slavic Hevellers in Brandenburg.

After his death in 1123, his son Albrecht, born around 1100, continued the expansive house policy with the second phase of the German East Settlement .

He turned out to be a skilled diplomat and established close contacts with Pribislaw-Heinrich between 1123 and 1125. The Hevellerfürst became the godfather of his first son Otto I and gave him as a godparent gift the teeth that adjoined Ascanian free float. 1128 died the Margrave of the Nordmark , Heinrich II. Von Stade , Albrecht's brother-in-law. Albrecht felt himself to be an heir. However, there was still a cousin, Udo IV von Freckleben, who made claims. Violent clashes broke out between the two of them. Albrecht's followers killed Udo in 1130. The act withdrew Albrecht from the favor of the king. In 1131 to the Reichstag in Liège, Konrad von Plötzkau , a close relative of the Stader family , was appointed Margrave of the Nordmark .

In 1127 Pribislaw came to power as Hevellerfürst on the Brandenburg . He had the German-speaking baptismal name Heinrich, hence the double name Pribislaw-Heinrich, which is usually read. His predecessor Meinfried was already a Christian . Therefore it could be concluded that Pribislaw-Heinrich had received baptism as a child. Later medieval chroniclers idealized the development and relocated the baptism to his princely period. He was closely connected to the German nobility and apparently received the title of sub-king from the emperor in 1134 (later revoked). This allowed the Germans to temporarily loosely tie the Heveller area (on both sides of the Havel between Potsdam and Brandenburg an der Havel ) to the Reich . The disputed eastern border thus ran between the two Elbe Slavic tribes of the Heveller and Sprewanen . Geographically very roughly drawn, it followed the courses of the Nuthe and Havel rivers . Jaxa von Köpenick ( Jaxa de Copnic ) resided east of this line .

In order to regain royal grace, Albrecht took part in King Lothar's Roman procession in 1132/33 and was successful. When Konrad fell in Italy in 1133, Albrecht became the bear of Lothar III. 1134 enfeoffed as Margrave of the Nordmark at the Reichstag in Halberstadt . He took over the imperial power over the eastern Lutizenland from the Peene to the Lausitz.

But the emperor wanted to put a stop to an excessive expansion of power by the Ascanian from the start; therefore, in the same year, Pribislaw-Heinrichs was raised to the royal rank. But as early as 1134 Albrecht was able to wrest a binding promise from the childless prince of Heveller. After Pribislav's death, Albrecht the Bear was to take over the inheritance and successor.

In 1147 a new Christian crusade was started against the Wendish pagans, the so-called Wendenkreuzzug . This took place parallel to the preparations for the 2nd crusade to the Holy Land. Danes and Poles also took part in the crusade. It was not just about religious goals, but about the acquisition of land and sovereign rights. The cross army consisted of two armies. The first army group moved north to the home country of the Abodrites , the second army group gathered in Magdeburg and moved to Havelberg . There they prevailed and the nominal bishop Anselm von Havelberg succeeded in entering his actual bishopric for the first time, which he maintained from then on. While Albrecht was content with taking the Burgwards in Havelberg, German knights advanced in private ventures between Elde , Rhinluch and Rhin and founded their own small domains there, which were, however, given up again a short time later.

The area around Havelberg was finally secured. In the neighboring regions of Prignitz and Ruppin, the first foundations for the subsequent settlement were created. The main army of the crusaders, headed by Albrecht, then moved from Havelberg to the core area of the Lutizen , the Peeneland . The army campaign went via Demmin to Stettin and thus penetrated into the domain of the already Christianized Pomorans , where the advance came to a standstill. The special thing about this crusade and the devastation is that the Havelland was spared, although the Hevellers continued to practice their old pagan beliefs and the landscape bordered directly on German domains. The prince of the Havelland Pribislaw-Heinrich von der Brandenburg demonstrated his Christian faith sustainably and publicly in order to keep any damage caused by Christian crusaders away from his territory. So he removed the image of the three-headed Triglaw venerated in Brandenburg , laid the royal diadem with his wife on the Petrus altar in Leitzkau and brought nine clergymen from Leitzkau to the Brandenburg region and gave them generous gifts. These precautionary measures worked. Furthermore, Heinrich and his wife had chosen Albrecht as their successor (in secret). Due to this succession arrangement, it was of no interest to Albrecht to destroy his later guaranteed property. As a result of the crusade, the Elbe Slavs achieved a military defensive success, but their inner cultural and civilizational strength was broken afterwards. The war-related losses and population decimation were too high. The colonization with German settlers, which had already started in 1143 with Adolf II , could thus take place on a larger scale.

Establishment of a feudal state under the Ascanian margraves (1150 / 1157-1320)

The first margraves:

|

Conquest of Brandenburg, formation of a contiguous territory, recognition as an imperial principality

The successful and permanent formation of a new territory was related to the efforts of his first margrave, who made his various scattered personal possessions, which still did not form a sovereign state on the legal level, and his royal official privileges (as margrave of the non-existent Nordmark, understood as "more offensive Defense area ”of the empire against possible incursions by Elbe Slavs into the old empire west of the Elbe) in a relatively structureless geographical area and in competition with many other medieval“ conquistadors ”ultimately formed a coherent state principality. The formation of the state of Brandenburg was ultimately the result of the work of an ambitious, determined and power-conscious person who was mainly concerned with his own hierarchical advancement process in the personal empire structure in the sphere of activity of the emperor.

Through the inheritance promised to Albrecht, Pribislaw ruled Brandenburg until his death in 1150. In the meantime, Albrecht I occupied the Zauche , the area south of Potsdam that Pribislaw gave to his son Otto as a gift. Albrecht was largely able to take over the Brandenburg without bloodshed. He had Spandau Castle rebuilt as an Ascanic castle. With these events various historians viewed the year 1150 (instead of 1157) as the actual beginning of the history of the Brandenburg region. The Heveller population , who in contrast to their prince still followed the old Slavic deities in part, was rather hostile to Albrecht's takeover. The Sprewanenfürst Jaxa von Köpenick , possibly a relative of Pribislaw-Heinrich, also made claims. With a mixture of betrayal, bribery, cunning and violence, as well as with Polish help, he succeeded in occupying Brandenburg and seizing power in the Hevellerland. On June 11, 1157 Albrecht the Bear was able to finally conquer the Brandenburg in battle. He drove out Jaxa and established a new sovereignty on Slavic soil . After the title had already been assigned to him several times before, Albrecht called himself Margrave in Brandenburg for the first time in a document dated October 3, 1157 ( Adelbertus Dei gratia marchio in Brandenborch ). With the new title "Margrave of Brandenburg", Albrecht signaled his goal of transforming the margraviate of the Nordmark from a royal fiefdom into a state sovereignty. This meant that Albrecht, who as Margrave of the Nordmark was only an official of the empire for its interests in the East Elbe region, established his own territorial rule with the formation of a Brandenburg Mark. The year 1157 is therefore considered to be the traditional founding year of the Mark Brandenburg. The transformation of the margravial office into a state sovereignty corresponded to the current trend. Shortly before that, the Wettin Konrad had obtained a house power in a similar way and thus laid the foundation for his own sovereignty. Perhaps it served Albrecht the Bear as a model for his own title designation that the Wettiner has since called himself Margrave of Meißen . In 1156 the march of Austria had become a duchy . These three territorial rulers (Brandenburg, Saxony and Austria) on the eastern border of the empire, at that time still with a low concentration of power, formed successful focal points for larger states in the empire. While the west of the empire was already permeated by complex rulership structures, there was still leeway in the east and rulership relations were still open and loose. Ultimately, this growth process of the three territories later led to competition between them (especially Brandenburg-Saxony and Prussia-Austria ). At that time, however, all three territories were still overshadowed by the position of power of the Guelph Heinrich the Lion, who united the duchies of Old Saxony and Bavaria in his hands and was looking to expand his power in the east.

The Altmark, the Prignitz and the Havelland now had a territorial center, the Nordmark became the Mark Brandenburg. From here Albrecht and the following margraves gradually penetrated into other regions of the former Northern Mark, which other princes had appropriated in the course of the previous Wendenkreuzzug of 1147. This took place partly in a warlike manner, partly on a contractual basis. Since Albrecht was dependent on noble support in taking possession of the Brandenburg, it is likely that the newly acquired Heveller area was only partially under the control of the Ascanians and that the latter had to transfer lordships to his allies in return. The actual core area of the newly founded Mark Brandenburg initially consisted only of the middle area between Brandenburg / H. and Nauen. Ultimately, it was a relatively small core area, whereby the margrave succeeded in acquiring further property and rule rights in the northeastern Elbe-Havelwinkel around Rathenow and Havelberg . In addition, the Askanians had rights from before 1150 in the northern and eastern Altmark, with Salzwedel and Stendal . Albrecht may have extended his margravial powers in the Nordmark to this area as well. However, Albrecht and Otto I rarely stayed in the Altmark. Nevertheless, Albrecht included his allodial possessions in the Altmark in the state expansion that followed after 1160, with the aim of establishing claims to rule there. His allodial possessions did not yet represent sovereignty , but were one level of rights below that in relation to the empire. Basically, Albrecht strove for the dignity of Duke of Saxony because of his Billunger inheritance , which he only held from 1138 to 1142 and then had to leave it to his cousin Heinrich the Lion .

The city of Brandenburg was further developed into a center of power. However, the Brandenburg was still considered royal property, so that a royal burgrave was installed there.

The ruling system of the margrave was based on a tiered feudal system . Many young aristocrats followed him to Brandenburg. Once there, the margrave rewarded them with land and allowed them to build castles to protect their property. On their estates, the knights of the lower and middle levels had jurisdiction over the inhabitants of their land. They had a complex service and duty relationship with their margrave, who in turn served the German king as bailiff , who was tasked with securing the empire to the east.

Albrecht the Bear had vigorously pushed the process of territorialization forward, but it was not yet over when he died in 1170. The process of becoming a state lasted until 1250. After Albrecht's death in 1170, his son, Otto I, became Margrave of Brandenburg. Emperor Friedrich I Barbarossa recognized the title two years later. The mark was thus established as a new imperial principality. Otto I. operated the expansion of the margraviate's independence. Until then, the mark was one of many royal / imperial fiefdoms. With the recognition of the mark as an imperial territory, it now became an imperial intermediate level in the "feudal pyramid", to which all of the aristocrats of the mark were subject to fief. As everywhere in the empire, conflicts arose between secular and often imperial direct spiritual power, which were directly subordinate to the emperor and the highest imperial courts.

The area was poor in people (a few ten thousand inhabitants) and only sporadically and not systematically populated. The few existing rulers of the margraves consisted of simpler castles. These did not yet form a network with one another, but were isolated from one another. The cultural level of the old resident population was lower than in the areas of the old empire. A state rule with clear borders, laws or regulated income had to be formed on the basis of a planned settlement ( state expansion ) with the limited technical and logistical means of that time. The first wave of settlements from the Altreich took place by 1170, recruited by the margraves. The settlers came in particular from the Altmark , the Harz , Flanders (hence the name Fläming ) and the Rhine regions. The systematic colonization of the country was carried out by enterprising knights, merchants, craftsmen and farmers from the old German tribal areas. Locators were tasked with recruiting people willing to settle in the west of the empire and with founding towns and villages. The existing Slavic population was also included. This led to a merger of the German and Slavic ethnic groups. The Germanization of the country as a result of the numerical superiority of the German immigrants was largely peaceful. The share of the Cistercians in the development of the country remained modest, and research has long overestimated it. In agriculture, the three- field economy replaced the wild field-grass economy . The new settlers retained their personal freedom and were exempt from taxes for a certain period of time, while the merchants were exempt from customs duties. The Zee and Dutch played an important role . After devastating North Sea - storm surges they like moved to new settlements. Her experience in dike construction helped with the drainage work along the Elbe and Havel , which were tackled in the 1160s.

Territorial expansion, Hanseatic League, founding of cities, promotion to the electoral college, formation of the estates

From Brandenburg / H. the Ascanian margraves expanded their rule further east. The territorial expansion of the early period did not yet correspond to the dimensions of the high medieval Mark Brandenburg. Only the Ascanian homeland, the Zauche and parts of the Havelland were included. Only in the following 150 years did the margraves gradually expand the territory. The three Hochstifte , which were founded as separate clerical principalities, were not part of their dominion .

At the same time as the Ascanian efforts, efforts by other princes began to establish their own rulership districts in the area between the Elbe and Oder with the help of the country's expansion . The dukes of Pomerania were able to occupy large parts of the later Margraviate of Brandenburg. The Wettins advanced from the south, while the Piasts asserted property rights in the east . The Ascanian margraves grew their most important competitors in the Magdeburg archbishops, who tried to expand their territory further to the east. Archbishop Wichmann , in particular , was responsible for developing the country by founding cities, for example by awarding city rights to Jüterbog in the south of the Mark.

After the Havel- Nuthe line had formed the eastern border of the Ascanian domain for a long time , the Ascanians prevailed against their neighboring competitors at the beginning of the 13th century as a result of the continued expansion policy to the east and northeast. The newly acquired area was the landscapes of Barnim and Teltow to the east of the Nuthe, north and south of the Spree. Since the place Spandau was now in a favorable geographical location of the territory acquired by then, the Ascanian margraves Johann I and Otto III. (1220 to 1267) the longest period of their rule there.

The expansion to the east also continued. This became possible because the Guelph Duke Heinrich the Lion had lost control of his duchies of Saxony and Bavaria piece by piece in the second third of the 12th century and thus left a power-political vacuum in the north of the Holy Roman Empire. The neighboring princes also pursued their own expansion goals in this environment that was politically insecure, which led to numerous armed conflicts. The Ascanian interest was aimed at a connection to the Baltic Sea , at the expense of the Duchy of Pomerania , at that time one of the most important international trading markets, while Pomerania expanded its influence into the Uckermark. Pomerania sought additional protection by drawing on Denmark. This bilateral expansion policy led to conflicts between the rival interested parties ( kings of Denmark , dukes of Silesia and Pomerania including Henry the Lion as the temporary liege lord of the Pomerania). The Battle of Bornhöved in 1227 secured the Brandenburg claim to Pomerania. Emperor Friedrich II formalized this in 1231 when Pomerania was enfeoffed to the Margraves of Brandenburg, which was confirmed in the Treaty of Kremmen between the Princes of Brandenburg and Pomerania in 1236 , including the cession of the Stargard, Beseritz and Wustrow lands to the Ascanians in Brandenburg. With the Treaty of Landin between the Griffin and Ascanian princes in 1250, today's Uckermark (1250) finally came to the mark.

Conflicts also broke out with the Archbishops of Magdeburg . These raised sovereign claims to the places they founded in the Mark. After the Margraves of Meißen tried to expand their influence to the north, the six-year Teltow War and the Magdeburg War broke out , which the Ascanians from Brandenburg won and thus gained the last parts of the Barnim and Teltow. In the middle of the 13th century, the Ascanians had finally gained the upper hand over their competitors. They had continuously expanded their territory and dominated a large territorially contiguous area.

Urban settlements emerged especially in the middle of the 13th century, often along the course of long-distance trade routes and rivers. The Havel, which partially runs from east to west, and the confluent Spree formed the inner center of the Brandenburg chain of cities. Berlin received city rights in 1246 and Frankfurt (Oder) in 1253 . Long-distance trade developed. Intensive trade relations developed particularly between the cities of the Mark and the Hanseatic League . The feudal constitution gradually began to transform itself into a rural one. Knights and municipal patricians were granted written rights by the margrave in the field of jurisdiction and taxation. The first provable Brandenburg state parliament with parts of the knighthood took place in Berlin in 1280. The interior blooming country gained more and more political weight in the Reichsverband. In 1252 Margrave Johann I participated in the election of the emperor for the first time . Brandenburg began to rise into the ranks of the politically exclusive electoral principalities. The country extended its border further east of the Oder . In 1260 the Neumark was conquered.

Albrecht III. After the death of his sons Otto and Johann (around 1299) he gave his son-in-law Heinrich II. von Mecklenburg - by buying it in pretense - the rule of Stargard . With the Treaty of Vietmannsdorf in 1304, the transfer was finalized after Albrecht's death. An alliance with the Swenzonen brought the hoped-for access to the sea. The Pomeranian princes had fallen out with the nominal lord of the Duchy of Pomerania from 1306 , Władysław I. Ellenlang . In 1307 the margraves won the lands of Schlawe , Stolp and Rügenwalde . The Teutonic Order opposed their expansion into the Pomeranian heartland with Danzig (conquered in 1308 up to the city castle) under Margrave Waldemar and his brother Otto IV . Władysław Ellenlang had called on the order of knights for help. In the North German Margrave War , the Teutonic Order expelled the Brandenburgers from Danzig and bought their claims to Pomeranian in the Treaty of Soldin 1309. The knights of the order then acted as sovereigns of their own accord and overruled Polish claims.

After the death of the daughter of Albrecht III, Beatrix , there was an inheritance dispute between the Brandenburgers and Heinrich II from Mecklenburg over the rule of Stargard in 1314. In 1315 Margrave Waldemar occupied the land of Stargard. Heinrich II was able to defeat Waldemar near Gransee and in the Peace of Templin on November 25, 1317, he was finally granted the rule of Stargard. This sealed Waldemar's defeat against a coalition of north German princes led by the Danish king. Access to the Baltic Sea with the lands of Schlawe, Stolp and Rügenwalde was lost to Duke Wartislaw IV of Pommern-Wolgast. With the deaths of Waldemar (1319) and his underage cousin Heinrich II (1320), the Brandenburg line of the Ascanians became extinct in the male line.

Time of turmoil and weakening of the central sovereignty

In the 14th century the mark fell into a serious crisis. After the Ascanian dynasty died out, the country had no central rule. The internal conditions became more and more disordered and were mainly shaped by the law of the thumb. Neighbors attacked the Mark from all sides and claimed parts of the country.

Brandenburg Interregnum (1319 / 1320-1323)

The Brandenburg Interregnum lasted from 1319/1320 to 1323. Initially, the best chances to emerge from the turmoil as the new elector lay with Wartislaw IV , Duke of Pomerania-Wolgast (1309-1326) and Rudolf I , Duke of Saxony-Wittenberg (1298 -1356). In the end, Ludwig IV , Duke of Upper Bavaria (1294-1340) seized the opportunity to expand his domestic power . The Wittelbacher first prevailed in the battle of Mühldorf on September 28, 1322 against his Habsburg rival for the throne . Then belehnte it in April 1323 as his son Ludwig I with Mark. The power play around Brandenburg did not end that, it had only just begun.

Under the Wittelsbacher (1323-1373)

The people's expectations that the Wittelsbach would create order in the country were not fulfilled. The political interests of the new masters were directed to other territories. The nobility and cities became increasingly independent from the margrave. The noble families exercised their own power in their domains. They held margravial castles whose income they claimed and from where they threatened trade routes with raids. Abandoned by the sovereign, the cities themselves took measures to protect them. In 1323 22 cities had signed a union for the maintenance of the peace. Many Brandenburg cities joined the Hanseatic League.

Berlin - Citizens of Cölln killed Nikolaus, Archdeacon of Bernau, in 1324 . The latter appeared as a party member of the Pope against the emperor . The Pope then imposed the interdict on the twin cities . A Pomeranian-Brandenburg War arose with the Duchy of Pomerania .

After the death of Emperor Ludwig IV. In 1347, Ludwig I was confronted with the false Waldemar , who pretended to be the last surviving Ascanian. This was initially recognized by the new Roman-German King Charles IV of Luxembourg , who was enemies with the Wittelsbachers. Despite the certainty that he was a con man, almost all cities paid homage to him. After heavy fighting against the "false Waldemar", the Wittelsbachers reached an agreement in 1350 at the cost of considerable territorial losses. In 1351, Ludwig gave the mark to his younger half-brothers Ludwig II and Otto V in the Luckau Treaty in order to be able to rule Upper Bavaria alone in return . Ludwig II finally forced the false Waldemar to renounce his margrave dignity.

The plague , which was rampant in Europe at the time, spread to Brandenburg and claimed many victims. Jews were held responsible for this and by 1354 a wave of persecution of the Jews began.

Despite the desperate internal conditions, Charles IV confirmed the right to vote when the king was elected with the Golden Bull of 1356, which made the mark attractive to other princes. When Ludwig II died in 1364/1365, Otto V took over the government, which he soon neglected. In 1367 he sold the Lausitz mark , which had previously been pledged to the Wettins , to Charles IV. A year later he lost the town of Deutsch Krone to the Polish King Casimir III.

Under the Luxembourgers (1373-1415)

From the middle of the 14th century, Charles IV made several attempts to acquire the mark for his house in Luxembourg . For him, it was primarily about Brandenburg's voting voice ( he already had the Bohemian one ). With their help the elections of a Luxembourg emperor should be secured. In 1373 the emperor was finally successful against payment of 500,000 guilders to Otto V ( Treaty of Fürstenwalde ). At the Landtag in Guben in 1374, the Margraviate of Brandenburg was included in the states of the Bohemian Crown . This was constitutionally questionable because it violated the Golden Bull issued by Charles IV himself . Significant measures taken by the regent included: the creation of the land register of Emperor Charles IV and the expansion of Tangermünde Castle into an imperial second or Brandenburg residence. Even under his nephew Jobst von Moravia , the power of the Luxembourgers in Brandenburg declined against the rural nobility. Under the Wittelsbach and Luxembourg margraves, the sovereign power declined and the importance of the aristocratic estates increased.

The important Neumark was pledged to the Teutonic Order.

Combating feuds and establishing peace in the transition from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance

Robber Baron War

The stronger aristocratic families had taken over. Everyone fought against everyone for power, resources and influence, for example for illegal customs revenue (highwaymen), for tribute money that was not lawful (mafia-like "protection money"). Traveling merchants and their escorts were attacked by the soldiers of the Quitzows, who were particularly violent in this civil war. The country was close to collapse. The aristocratic Quitzow family with their most famous representatives, the brothers Dietrich and Johann , led their disputes partly on behalf of the cities, but also against their clients. At the beginning of the 15th century, the Quitzows owned 16 castles and palaces in the Mark, including in Köpenick, Plaue and Friesack.

The feuding was not only in the market, but in other parts of the empire often a practice of enforcing one's own rights. Until then, the settlement of disputes through the involvement of courts with legally trained councilors was only common up to the level of the princely territories within the framework of the Reichslandfrieden . As a result, self-help and vigilante justice remained structurally required. Since the princely power was almost completely absent in Brandenburg, agreements to maintain the peace had to be organized by oneself - for example among the cities as a league of cities . Together they fought the peace breakers and, in addition to their own mobilization, brought in mercenaries. Whether the situation in the Mark corresponded to the typical conditions in the empire or was particularly negative remains a matter of dispute. A fundamental change in the power relations in the Mark was not sought by either side.

The attempts of the cities to defend themselves with mercenaries and to form protective alliances had failed. A Brandenburg delegation headed by Berlin-Cölln dignitaries traveled to the court camp of King Sigismund to pay homage in the spring of 1411 to ask for help against the marauding landed gentry. In 1411, at the insistence of the Brandenburg embassy, Frederick VI. , Burgrave of Nuremberg from the House of Hohenzollern , as hereditary captain in the Mark Brandenburg and gave him sovereign powers. This was done in recognition of his previous support in the election of the king on September 20, 1410 in Frankfurt am Main .

From a tactical point of view, Friedrich sent a confidante who arrived in the Margraviate of Brandenburg in June 1412. This was confronted with the anarchic conditions in the Mark and an opposition of the Brandenburg noble families. He demanded the surrender of the margravial castles and the income associated with them, which the local nobility had appropriated over the past hundred years. Thereupon the confidante Wend von Ileburg was ridiculed by the nobles as "trinkets from Nuremberg", which one could already deal with. The most dangerous robber barons the brothers Quitzow and Gans zu Putlitz from Altmark led the opponents of the new margrave. When Friedrich received homage after his arrival, a significant proportion of the nobility refused to do so - in contrast to the cities. This was the trial of strength between state law and princely law. Friedrich had a meeting of the estates convened. At the meeting of the estates on July 10, 1412 in Brandenburg an der Havel, he announced his program, in which "the law should be strengthened and the injustice insulted" and order in the Mark Brandenburg should be restored. He allied himself with the cities, but also outside Brandenburg he found an effective ally in the Saxon Ascanian Rudolf , who lent him a larger artillery, the Faule Grete . The Archbishop of Magdeburg also supported the Hohenzollern. Both of the Mark's neighbors were interested in a safe country to pass through. With persuasion and armed force, Frederick I prevailed in the Mark between 1412 and 1414. Both sides prepared well for the dispute, the Quitzows reinforced their castles, while Friedrich had cannons poured. In several campaigns against the Quitzows, their power was broken until in February 1414 he conquered the castles Friesack , Plaue , Golzow and Beuthen with the help of Faulen Grete . Dietrich von Quitzow fled in time, but Hans von Rochow appeared in a penitent's garb and threw himself at Friedrich's feet, the rope already around his neck, he pleaded for sparing, just as the merchants used to do before him. Friedrich treated the rebellious nobles with moderation. The Gardelegen castle of the Alvensleben and the Beuthen castle were only routine matters for Frederick's troops. The campaign against the castles, known as the robber baron war, was successful across the board for Friedrich. The conflict was ended on March 20, 1414 by the Diet convened by Friedrich in Tangermünde . On this he proclaimed a state peace order, which obliged the estates to provide joint assistance and decreed the end of the lawless state through the general binding force of the ordinary courts. This marked the beginning of the long process of regaining the lands and rights that the Ascani had won.

Transfer of the electoral dignity to the Hohenzollern, defense against external attacks, consolidation inside

Tangermünde, the city on the Elbe, became the first Brandenburg residence of the Hohenzollern family. By successfully cleaning up under the landed gentry, Frederick I had qualified as ruler over the nobility. But the cities were also autonomous due to the weakness of the central power, which Frederick I could not change.

Friedrich, the strong man who had brought order into chaos, had fulfilled the king's expectations. Four years later, on April 30, 1415, at the Council of Constance , the latter granted him the dignity of Margrave of Brandenburg, arch chamberlain and elector of the empire. The tribute to the Brandenburg estates took place in the same year on October 21 in Berlin in the hall of the Franciscan monastery . The formal enfeoffment with the Kurmark was carried out by King Sigismund, again at the Council of Constance, on April 18, 1417. Friedrich VI was elector. Nuremberg referred to as Friedrich I of Brandenburg in the following .

With varying success and equally changing allies, Elector Friedrich I asserted himself against internal and external adversaries in the period that followed. The Pomeranian Griffin Duke Swantibor had been governor of the Mittelmark, part of the Mark Brandenburg, since 1409. When Frederick I was appointed "Supreme Captain and Administrator of the Brands", Swantibor held on to his office as governor of the Mittelmark. This led to armed conflicts between the two sides, including the battle at Kremmer Damm . The sons of Swantibor continued the warlike course against Brandenburg. In the spring of 1420, Elector Friedrich I had to advance in Brandenburg against the Pomeranian dukes Casimir and Otto of Pomerania-Stettin , who threatened his lands. He defeated the dukes at the Battle of Angermünde in March 1420.

Due to the growing estrangement from the emperor, he could not avoid the transfer of the Middle Elbian electorate of Saxony to the margraves of Meissen in 1423 . The hoped-for unification of the Saxon and Brandenburg electoral titles for the Hohenzollern failed. The Wettins moved up as a new powerful neighbor on the direct border with Brandenburg. An intense and rival history of relations between the two states about dominance in Central and Eastern Germany began, which stretched over centuries. The mutual dynastic relationships in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries were primarily geared towards cooperation and primarily meant the mutual transfer of cultural assets, experts and knowledge carriers and a lively exchange in intellectual and economic life.

Frederick I had not been in Brandenburg since 1416, except for military campaigns. From the Cadolzburg in Franconia, Friedrich could not properly conduct the affairs of Brandenburg. In addition to diplomatic defeats, there was also mockery about the military defeat in front of Vierraden. The feud between Brandenburgers and Pomeranians, which was almost constantly fought in the Middle Ages , had ignited again and again. Friedrich had to break off the siege of the castle Vierraden in the Uckermark region in the war against Pomerania-Stettin in 1425 because his nobility refused to obey him and he had to abandon the borrowed artillery. That was probably the last impetus for him to assemble the estates in Rathenow and transfer the governorship to his first-born son Johann . In 1426, Friedrich I withdrew into his Frankish possessions in a disgruntled manner. As a merit, the gain of the support of the land nobility for the sovereignty remained. Since then there have been no more dominant feuds between the sovereign and the influential landed gentry. The large families of the country from then on became more and more closely connected with the sovereign, entered his service and behaved loyally.

As governor, Johann was primarily concerned with the cities. In 1429 alone there were two open conflicts, in the Stendal uprising and in the unrest in Salzwedel . In the same year, Margrave Johann lost a showdown with Frankfurt / Oder. The conflict with the cities in 1431 led to an alliance between Berlin, Cölln, Brandenburg an der Havel and Frankfurt (Oder) . John's power in Brandenburg was weakened by these conflicts, making the Mark an interesting target for the Hussites . These were possibly on revenge against Friedrich I and the bishop of Lebus Christoph von Rotenhan , who had led the imperial army in the Fifth Crusade against them in 1431 . In the middle of March 1432, four Hussite detachments with a total strength of 7,000 to 8,000 men set out from Bohemia. A first foray into the Mark Brandenburg took place around April 6th and 7th, 1432 by a Hussite reconnaissance contingent. On April 7, 1432, the Hussite detachment attacked the area around Seelow and from there moved south again towards Frankfurt (Oder). A contingent from Frankfurt attacked the reconnaissance department of the Hussites in Müllrose around April 10, 1432 . The actual main Hussite army moved northwards from Guben around April 11, 1432 and reached Frankfurt (Oder) on April 13, 1432 and then moved on to Lebus . On April 17, 1432 the Hussites overran Müncheberg . Buckow and Strausberg followed on their train . The campaign was likely to go on to Eberswalde and on to the Cistercian monastery of Chorin , since monasteries of this order had previously been targets of Hussite looting. On April 23, 1432, the field army stood before Bernau . The “ Battle of Bernau ” ultimately ran like the previous city storms. After the suburbs were burned down, several attempts at storming began, which could be repulsed. The Hussites are said to have left on the same day. The Hussites left the Mark Brandenburg from Bernau. The victory at Bernau became a legend over the next few centuries.

In 1437 Friedrich I transferred the government of the Mark Brandenburg to his second son, Friedrich II. He ruled the Mark directly. From 1437 to 1440 Friedrich II succeeded in further strengthening the sovereign authority, while at the same time a high level of predatory crime and a pronounced legal mentality in the country continued. In order to improve the manners of the nobility, Frederick II founded the Swan Order in 1443 , whose bearers were obliged to behave respectably according to knightly principles. This amounted to an honorable submission and at the same time a peace agreement.

Restriction of urban autonomy, relocation of the residence to Berlin

The sovereignty began to restrict the autonomy of the cities with increasing success. The trading and Hanseatic city of Berlin had developed into a center of the state during the weak state rule. In Berlin city federations were closed in which this city acted as the head and thus acquired a political leadership role among the cities. There the estates came together, either requested by the margrave or against his will.

In 1440 a power struggle that lasted several years began between the sovereign and the citizens of Berlin and Cölln. This began when a dispute broke out between the patrician-dominated council and the craft guilds, in which Friedrich II, who was currently residing in the High House in Berlin, intervened as an uninvited arbitrator. The city initially refused to receive the elector and his entourage in the town hall. As a result, the elector overthrew the patrician rulership of the city in 1442. He canceled the previous merger of the two cities of Berlin and Cölln and forbade them to enter into alliances and participate in the Hanseatic Days . Since he entered the twin cities in August 1442 with 600 armed knights, the council had no choice but to agree under pressure. The changes provided that the elected councilors and the mayor require his approval. When he abdicated, the old council gave the elector the keys to the town hall. The elector handed these over to the newly appointed councilors, with the indication that these had to be handed over to him, the sovereign, upon request. He dictated a treaty to the council on August 29, 1442. In it he withdrew from the city the court and staple rights that had been acquired since 1391 . As a sign of the new legal situation, the Roland , the sign of market law and its own jurisdiction , has been removed. He forced the city leaders to give him land to build a castle. He was personally present when the foundation stone was laid for the castle. He made it clear that he intended to establish himself in the city in the long term. An electoral judge has now moved into the joint town hall.

Elector Friedrich II tried to bring about an alliance of princes against the cities in northern Germany. In February 1443, in addition to the Elector, the King of Denmark, the Dukes of Pomerania, Mecklenburg, Saxony and Braunschweig, who were particularly committed in this regard, gathered in Wilsnack in the Prignitz to discuss ways and means of breaking urban autonomy in their countries. Neither the Mittelmärkische Städtebund nor the Hanseatic League reacted to the violation of Berlin's autonomy.

The citizens of Berlin and Cölln now resisted the abolition of urban privileges, and their inner-city conflicts were no longer relevant. The renewal of the Hanseatic Tohopesate in May 1447, tensions between the Duke of Lauenburg and Friedrich II, his involvement in war with Pomerania and his own reinsurance with other Brandenburg cities may have encouraged the two cities to do so.

The dispute between the Elector and Berlin-Cölln began with rebellious speeches in wine cellars and other places. Customs officers, judges and other officials were forced to stop their work, then the court chancellery in the high house was looted in search of files that could be used against the citizens, and finally the weir on the side arm of the Spree was opened and the building site of the Berlin City Palace was flooded. The council had secured the support of other cities in the march, so they locked up one of Friedrich's ambassadors, court judge Balthasar Hake , who was supposed to summon the leaders of the uprising to the court in Spandau. Frederick II assessed the resistance so strongly that he did not dare to suppress it militarily. Above all, he relied on time, negotiated with the other cities, and the alliance dissolved, Berlin and Cölln remained isolated. At the end of May 1448 the councils had to give in meekly and accept the treaty of 1442. The submission of Berlin-Cölln (1442–1448) marked a decisive break in urban autonomy. It was the first complete victory of the principality over the bourgeoisie and in other countries of the empire also led to the fact that the princes consistently took action against urban autonomy in their territories.

With the construction of the Berlin Palace , the electors created a modern and permanent residence as the center of the market alongside Tangermünde and the Spandau fortress . In 1447 the elector won the right to appoint his bishops to elect his regional dioceses. The elector tried to make this serviceable for himself. The larger cities had to terminate their membership in the Hanseatic League . The increased political influence in the Hohenzollern Mark was followed by further foreign policy successes. The Archdiocese of Magdeburg now renounced its old feudal claims from 1196 to the mark and the weakened Teutonic Order gave the Neumark back to the Hohenzollern in 1454/55. In 1462 the central area around Cottbus, Peitz, Teupitz and Bärwalde came to the Mark in 1462 from Niederlausitz, which was formerly part of the Mark.

In the Uckermark, the areas of Schwedt, Vierraden and Löcknitz came back to Brandenburg. This happened when the Pomeranian griffin duke Otto III. von Pomerania-Stettin had died in 1464 and Elector Friedrich II raised a claim to this part of the country due to the Brandenburg suffrage, which had never been clarified. On January 21, 1466, the Griffins Erich II and Wartislaw X. took their duchies in the Treaty of Soldin from the Brandenburg Elector as a fief. However, since the feudal contract was not fulfilled, the War of the Szczecin Succession broke out , in the course of which the Brandenburgers conquered several cities on both sides of the Oder in 1468. Finally, in 1469, after the unsuccessful siege of Ueckermünde, there was an armistice. Its extension was the only result of the negotiations held in Petrikau at the beginning of 1470. While Erich II raided Neumark in May 1470, the Brandenburgers secured themselves with Emperor Friedrich III. the recognition of their claims to Pomerania. This finally enfeoffed the Brandenburgers with the state of Stettin in December 1471 and ordered Erich II and Wartislaw X to recognize the feudal sovereignty of Brandenburg. Through the mediation of Duke Heinrich von Mecklenburg , the Peace of Prenzlau was concluded at the end of May 1472 . The Pomeranian dukes and estates had to pay homage to the elector who retained the conquered territories.

In 1470, after more than thirty years of reign, Friedrich II, exhausted, handed over the office to his self-confident brother Albrecht Achilles , who ruled the Mark until 1486. Achilles played a prominent role in imperial politics and consequently regarded Brandenburg as a neighboring country.

Elector Albrecht Achilles, a war hero, drove Pomerania out of the Uckermark in 1478/79. Since 1479 Achilles stayed outside of the Mark because of the imperial politics and his son Johann led the government from the Berlin Palace with Franconian officials. Securing the unity of the country was of great importance for the consolidation of electoral power. With the Dispositio Achillea in 1473 Albrecht Achilles divided the Franconian and Brandenburg lands of the Hohenzollern among his sons and forbade the dynastic division of the entire Brandenburg lands including future acquisitions. In this way, the same thing did not take place in Brandenburg that happened so often in the other territories of the empire: the territorial fragmentation through the division of inheritance. Securing territorial integrity was one of the prerequisites for the later rise of Brandenburg-Prussia to a great power. The mark was now separated from the Frankish principalities. Johann Cicero became margrave and elector, while the younger brother Friedrich became the progenitor of the Franconian Hohenzollern family in the 16th century. However, the Hohenzollerns remained aware of their common roots. The family branches worked closely together in the 16th century. Family days were held at which court, house and religious affairs were discussed. 1482 received (who of the two?) The lien over the Duchy of Crossen including Züllichau and Sommerfeld . Since 1479 Albrecht Achilles stayed away from the Mark through his involvement in imperial politics. His son Johann Cicero took over the government from the Berlin Palace with Frankish officials. The peaceable Elector Johann (1486–1499) worked on expanding his territory, lived in the castles of the Mark and cared less about imperial politics, for which he had not been adequately trained. The direction of Brandenburg's foreign policy remained the same. Pomerania recognized the Brandenburg feudal lordship in 1493. In 1490 the rule of Zossen came to the mark.