Friedrichstadt

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 54 ° 23 ' N , 9 ° 5' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Schleswig-Holstein | |

| Circle : | North Friesland | |

| Management Community : | North Sea Treene Office | |

| Height : | 2 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 4.03 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 2653 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 658 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 25840 | |

| Area code : | 04881 | |

| License plate : | NF | |

| Community key : | 01 0 54 033 | |

| LOCODE : | DE FRI | |

City administration address : |

Am Markt 11 25840 Friedrichstadt |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Christiane Möller-v. Lübcke ( CDU ) | |

| Location of the city of Friedrichstadt in the district of North Friesland | ||

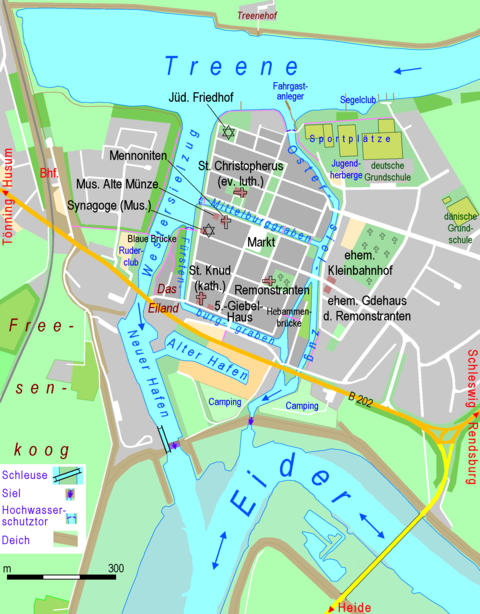

The city of Friedrichstadt ( Danish: Frederiksstad , North Frisian : Fräärstää , Low German : Friesstadt , Frieestadt , Friechstadt , Dutch Frederikstad aan de Eider ) is located between the rivers Eider and Treene in the district of North Friesland in Schleswig-Holstein . The climatic health resort forms an administrative community with the North Sea-Treene office , the office runs the city's business.

Friedrichstadt was founded in 1621 by the Gottorf Duke Friedrich III. founded and is now a high-ranking cultural monument . Duke Friedrich III. aimed at the establishment of a trading metropolis and brought Dutch citizens, especially the persecuted Remonstrants , to the place and granted them religious freedom . As a result of this measure, members of many other religious communities also settled in Friedrichstadt, so that the place was considered a "city of tolerance". Today five religious communities are still active.

The buildings of the Dutch brick renaissance and canals shape the cityscape of the "Dutch town" with almost 2600 inhabitants, which today lives mainly from tourism. The planned city has no further districts.

geography

location

Friedrichstadt is located in the Eider-Treene lowland at the confluence of the Treene tributary into the Eider . The area in the marshland only became habitable in 1573, after Adolf von Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf had the Treene dammed here so that it could no longer follow its original bed. Located under the city five feet piled clay soil , the deeper on clay and peat layers rests.

The settlement area is limited to the north by the broad lower reaches of the Treene and to the south by the Eider. The connections between the two limit the old town to the east and west. They are connected to each other by two canals . The central moat in the middle leads past the northern edge of the market square, the Fürstenburg moat forms an angle around the southwest and south of the old town.

Since the 1960s, a dike with a lock and two sewer systems has separated Friedrichstadt from the Eider. Instead of the historic dike directly in front of the old town, the B 202 now runs , and the historic sluices on the edge of the old town no longer exist. Up to the weir system and the Nordfeld lock , the Eider is a tidal body of water , the Tideeider . The Eider Barrage , inaugurated in 1973, is only closed when storm surges occur , but allows normal tidal currents through.

Two sluices with three, originally four sluices connect the Treene with the Eider and drain the area around the confluence. The city center is therefore on an artificial island. In the south the Eider delimits the urban area, in the north the Treene. The east and west borders of the inner city are each formed by the Oster- and Westersielzug. Two canals that connect the Sielzüge flow through the city center: the Mittelburggraben and the Fürstenburggraben.

The Westersielzug is about 30 meters wide and four to five meters deep, the larger of the two main canals and, together with the New Harbor south of the “Eiderschleuse”, forms the main estuary of the Treene. The so-called Eiderschleuse includes, in addition to the actual lock, a sluice structure with three sluices . The Ostersielzug is on average only about ten meters wide and two to three meters deep. It is drained by the so-called "flushing sluice" in the Eider (a literal translation of Spuisluis , the Dutch word for sewer ). The other canals in the city are even smaller. If the water level in the Eider is too high to sink when the storm floods, even at low tide, the inland water of the Treene can reach threatening heights. That is why there are stem gates at the upper ends of Ostersielzug, Mittelburggraben and Fürstenburggraben with which the old town can be protected against flooding from the inland.

Neighboring places

Nearby larger cities are Husum in the north, Tönning in the west and Heide in the south and Schleswig , Rendsburg and Kiel in the east. Neighboring communities are Koldenbüttel in the west and north, Seeth and Drage in the east, all in North Friesland . On the other side of the Eider, the Dithmarsch community of Sankt Annen joins in the south . To the east of the city lies the historic Stapelholm landscape .

history

Ambitious foundation plans in 1620/1624

The cause for the foundation of the city was the plan of Duke Friedrich III. von Schleswig-Gottorf to upgrade his country to the center of a trade line from Spain via Russia to the East Indies. In order to establish a strong trading port on the North Sea coast, he offered the Dutch , the then leading waterworkers and traders in Europe , namely the remonstrants persecuted in their homeland such as Johannes Narssius , Willem van Dam and his brother Peter from Amersfoort , religious freedom in an exile settlement with Dutch official language within his territory. He followed the example of his uncle and competitor Christian IV , King of Denmark and Duke of Schleswig and Holstein, who founded Glückstadt on the Elbe in 1617 for similar reasons and with similar methods.

Friedrich III. prevailed against opposition from the nearby Tönning , where traders feared the new competition, and his mother Augusta , who was decidedly against letting other than Lutheran religious communities into the country. In 1620 he issued two octroys , which guaranteed the Remonstrants land, religious freedom , economic privileges, Dutch as the official language and an administration based on the model of Amsterdam and Leiden .

On September 21, 1621, the first house construction in the planned city began. This house was intended for the Mennonite builder Willem van den Hove , who represented the duke and played a key role in the early urban development. From 1623, van den Hove brought more financially strong Mennonites to the city. In 1622 the duke had ten more houses built by the Dutch dikemaster Hendrich Rautenstein from Stapelholm , which he was supposed to build in the "Dutch manner". By 1625, the entire southern half of the city was completed, the so-called Vorderstadt, in which the market square is also located.

Friedrich III. also tried to win over Spanish Jews ( Sephardi ) for Friedrichstadt, as they were considered to be particularly educated and capable of business. But the Spaniards, who saw Friedrichstadt as Dutch competition, prevented this, as did the salt trade that Friedrich had planned. It was not until 1675 that German Jews ( Ashkenazi ) moved to Friedrichstadt. At times they formed the second largest religious community.

Because of the city's strong urge to expand, many more citizens of various religions settled here. For their meaning and history, see the Religion section .

17./18. Century: war and Dutch domination

Due to the Thirty Years' War , which also affected southern Schleswig and Holstein severely from 1626 , the settlement developed only slowly. In 1630 the Remonstrants were able to practice their faith again in their homeland, so that many returned there. The expected economic upturn failed to materialize.

The magnificently expanded granary of the merchant and temporary governor of Frederick, Adolph van Wael, was given the name Old Mint , but the originally promised minting privilege never went to the city. In 1633, however, Friedrichstadt received city rights . Despite poor economic development, Friedrich continued to woo new residents.

Centrally located on the way to Eiderstedt, various troops repeatedly took the city during the wars of the 17th and 18th centuries. Wallenstein planned to set up Friedrichstadt as a naval port, although he never built up his intended navy.

In 1643, after rumors that the Swedes were approaching, the sluices were opened and the entire Friedrichstadt area flooded.

After the Danish king had razed Gottorf's Tönning fortress in 1715, plans arose at short notice to build a new one in Friedrichstadt.

The Dutch remained the dominant group of the population for a long time, as can be seen from the minutes of the Council in Dutch from the first half of the 18th century . The surprisingly hard winter of 1824, when many ships unexpectedly had to spend the winter in Friedrichstadt, also testifies to their lasting importance for Friedrichstadt. 80 percent of them had Dutch home ports .

A prominent refugee was the future French "citizen king" Ludwig Philipp , who in 1796, on the run from the French Revolution, worked for a few months under the code name "De Vries" as a tutor in the city and lived on the upper floor of the Neberhaus .

19th century: Schleswig-Holstein War, Prussia

The conflicts sparked by the rise of nationalism in the middle of the 19th century were to lead to tragedy in the city of religious tolerance. By the autumn of 1850, the Schleswig-Holstein war for the Duchy of Schleswig had spared the south-west of the country. After the Battle of Idstedt on July 25, 1850, the war was practically decided and the remaining Schleswig-Holstein troops withdrew to Holstein. From September 29 to October 4, 1850, however, they tried in a last effort to recapture the city occupied by Danish troops. The bombing of the city killed or injured 31 residents, 53 Danish soldiers died , and 285 houses were destroyed, including the town hall and the Remonstrant church . The city archives also burned down.

In the Second Schleswig-Holstein War in 1864, Friedrichstadt was occupied without a fight. The entire duchy came under Prussian administration and in 1867 became part of the unified province of Schleswig-Holstein . In the same year a district court was established, which existed until 1975. At this time Friedrichstadt was assigned to the Stapelholm region . A relic from this time is the farmer's bell , which is typical for all the places in Stapelholm. It is now on the square in front of the youth hostel.

In the municipal reform in 1869 Frederick city was, like all cities in the country until then outside the offices and landscapes had stood, the newly created district of Schleswig assigned, the westernmost tip it formed. During this time, the city also experienced a small economic boom, which resulted from the connection to the various transport systems. In 1854 the railway line to Tönning was built, in 1887 the march railway, which connected the city to the railway network, in 1905 a small railway established the connection from the other bank of the Treene to Schleswig, in 1916 a road bridge was finally built over the Eider, which made the previous ferry journeys over the river unnecessary let. As a result of these buildings, small industries also settled, typical for small towns in Schleswig-Holstein at the time.

From the 20th century

The Nazis also found in Friedrichstadt his followers: During the Nazi Party in the general election in 1928 only 21 votes and was therefore less than 1 percent, they got 1932 general election in July 660 votes, representing 47.1 percent. On April 1, 1933, the Jewish businesses were threatened by SA men who called for a boycott of the Jews .

During the Night of the Reichspogrom , SA men destroyed the synagogue and then the shops and apartments of the Jewish citizens. Hinrich Möller had all Jewish men arrested on the morning of November 10, 1938. They delivered three of the arrested to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp . More Jews fled to Hamburg, many of them came from there to the concentration camp.

During the district reform, which took effect on April 26, 1970, Friedrichstadt came to the district of North Friesland with the communities of Seeth and Drage . Together with Koldenbüttel , Uelvesbüll and Witzwort from the former Eiderstedt district , they formed the Friedrichstadt office .

At the end of December 31, 2007 the office dissolved again and Friedrichstadt became vacant; but it has its administrative business run by the North Sea-Treene Office .

Incorporations

On January 1, 1974, parts of the three neighboring communities Drage (then about 75 inhabitants), Koldenbüttel (then about 30 inhabitants) and Seeth (then less than ten inhabitants) were incorporated.

population

Population development

In absolute terms, the population in Friedrichstadt has hardly changed since the city was founded and has always remained below the expectations that Friedrich III. once had for the city. In the past 200 years there have been two major changes in the structure of the population. In the years after the bombing, the number of residents fell as a result of the economic hardship and could only be stabilized by the renewed upswing in the early days . After 1945 Schleswig-Holstein and thus Friedrichstadt was an important area for housing German expellees from the East. However, when the displaced moved to more economically prosperous areas, the number of residents almost fell back to the old level in the following years.

| year | Residents | year | Residents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1840 | 2,272 | 1946 | 3,648 | |

| 1855 | 2,449 | 1950 | 3,618 | |

| 1864 | 2,242 | 1970 | 3,079 | |

| 1871 | 2,186 | 1979 | 2,716 | |

| 1895 | 2,480 | 2003 | 2,496 | |

| 1906 | 2,662 | 2006 | 2,496 | |

| 1919 | 2,450 | 2010 | 2,393 | |

| 1939 | 2.146 | 2012 | 2,353 |

religion

Friedrichstadt has distinguished itself from the start as a city of tolerance in which various religious communities coexisted. However, some groups only existed temporarily in the city. The Unitarians, for example, were not granted permanent tolerance. The Jewish community was destroyed during National Socialism. Today there are congregations of German and Danish Lutherans, Remonstrants, Mennonites and Catholics.

Remonstrants

Friedrich III. When the city was founded, he particularly relied on Dutch remonstrants as settlers. The religious community came about through a rift within the Reformed churches in the Netherlands. The point of contention was the basic theological question of how strictly the Calvinist doctrine of predestination should be interpreted, i.e. to what extent every person can attain salvation who firmly believes in God. While the remonstrants were particularly successful in the cities of the province of Holland , the contraremonstrants (i.e. the stricter Calvinists) had mainly followers in the country; one of its leading representatives was governor Moritz von Orange . At the Dordrecht Synod in 1619, he pushed through the ban on all Remonstrant assemblies, whereupon many Remonstrants fled abroad.

The Remonstrants were never the numerically largest group in Friedrichstadt. However, since it mainly consisted of traders from the world trading power of that time, its community was as rich as it was politically important. Your church building in Friedrichstadt was the first explicitly Remonstrant in the world; today the community is the only one outside the Netherlands. As early as 1854, as it does today, the congregation received support from the Netherlands for building churches. This was and is rather unusual for the Remonstrant community, which emphasizes its autonomy, and indicates the special status of Friedrichstadt as the only community abroad. Today the community has 150 to 200 members and other "friends of the community". Services are held twelve times a year; for this comes the preacher from the Netherlands. Since the service abroad is not attractive to everyone, the Friedrichstadt Remonstrants have had to make do with other Protestant preachers in the course of history.

Mennonites

The Mennonites recruited by the city's founders still have an active community today. The first Mennonites came from Eiderstedt , where parishes had existed since 1560 (see also Anabaptists on Eiderstedt ), East Frisia and the Netherlands. In Friedrichstadt they initially formed four independent communities: Flemings, Frisians, High German and Waterlanders. By the beginning of the 18th century their number rose to 400, also due to other settlers from Hamburg, Lübeck and the Palatinate. The Mennonites were among the traders and artisans, so the communities were among the wealthier in the city. When the four congregations merged into one congregation in 1708, they bought the Alte Münze and set up a church and cemetery there. This could not prevent the slow decline of the Mennonite population since the 18th century. There has been no pastor in the city since 1925; and today the congregation is looked after by the Mennonite congregation Hamburg / Altona . Today there are still around 30 Mennonites living in Friedrichstadt who can celebrate a church service three times a year.

Catholics

Frederick III granted the Roman Catholic Christians. on February 24, 1624 a restricted freedom of religion, since he was dependent on the benevolence of Spain towards the settlement for his plans. The Catholic community is thus the first Catholic community in Schleswig-Holstein since the Reformation. She was allowed to build a church, but without a tower; She was not allowed to celebrate services in public. Dominicans looked after the congregation from 1627 to 1638 , and Jesuit missionaries from Belgium moved to the city in 1646 . The Catholic community always remained one of the smaller in Friedrichstadt, reaching its highest number of members around 1750 with 120 members.

Within the church, this congregation gave important liturgical impulses. In 1687, a German high mass was celebrated here for the first time , at which Holy Mass was held in the local language and not in the Latin that was customary up to that time. In 1694 the First Communion was recorded for the first time as part of a White Sunday ; It was not until 1775 that this became common in other areas of Germany. Another special feature was the parish priest's right to company ; this privilege lasted until the end of the 18th century. Despite its importance as the Roman Catholic center of the Gottorf Duchy, the number of members kept falling. Only with the expellees in 1945 did a significant number of Catholics return to the city for the first time after 1750.

Due to its early re-establishment after the Reformation, the Catholic parish is considered to be the Catholic mother parish on Schleswig-Holstein's west coast. The parish with about 80 members (year: 2003) has not had its own church since St. Knud was profaned in autumn 2003, but is still active in religious life. At the moment, Holy Mass is only celebrated in the building every 14 days on Saturdays. The interior of the church still has the appearance of a room intended for church services.

Jews

Frederick's attempts to settle Spanish Sephardi failed because of the resistance of the Spanish king. In 1675, however, it was possible to recruit German Jews . The parish grew particularly in the early 19th century. From 187 members in 1803 the number rose to 500 in 1850. For about 100 years it was the second largest religious community in Friedrichstadt, which made up to a fifth of the Friedrichstadt population. The Jewish community was one of the largest in Schleswig-Holstein and in the entire Danish state. Due to emigrating community members from the second half of the 19th century, the number of Jews fell to 32 by 1933; the last rabbi left the city in 1938. With National Socialism, the community was destroyed, so that in 1940 the last Jew appears in the city records. Today only two cemeteries, the building of the historical synagogue and 25 stumbling blocks remind of the Jewish community.

German Lutherans

The Lutherans came mainly from the immediate vicinity, but later also from southern Germany. The German Lutheran congregation quickly grew into the largest congregation in the city, which it still is today with around 1,700 congregation members. However, compared to remonstrants or Mennonites, it was comparatively poor. For the construction and maintenance of the church, the community was repeatedly dependent on donations from the Duke of Gottorf. The congregation was only able to start building its own church, the St. Christophorus Church , in 1643, 22 years after the city was founded. Today the community is organized in the parish of North Friesland within the Evangelical Lutheran Church in North Germany .

Danish Lutherans

The Danish parish ( Frederiksstad danske Menighed ) did not come into being until after 1945 and is organized in the Danish Church in South Schleswig (within the Danske Sømands- og Udlandskirker ). The community uses the local Mennonite church as a place of worship. The congregation, which shares a pastor's position with the Danish congregation in Husum , now has around 140 families as members.

Unitarians

At the beginning of the 1660s, several Polish brothers or Socinians , who had previously been expelled from Poland-Lithuania by the Counter-Reformation , settled in Friedrichstadt, Schleswig-Holstein, with the consent of the city council. The Polish Brethren were a Unitarian Church that emerged from the Reformation and rejected the Trinity and were in part close to the Remonstrants ( belief in reason ) and Mennonites ( confessional baptism ). The settlement in Friedrichstadt was initiated by the Unitarian preacher and historian Stanislaus Lubienietzki , who had previously hoped that the Polish brothers would find denominational recognition in a peace treaty after the withdrawal of the Protestant Swedish troops from Poland. After these hopes were dashed, he stayed at the court in Copenhagen in 1660 and later in Hamburg before he asked the Friedrichstadt city council to accept his religious community on March 1, 1662. After the council approved, many of them formally became members of the Remonstrant Congregation. The majority of the immigrant Polish brothers came from the German-influenced community of Straszyn near Danzig , many came from the Ruar and Voss families. They were both nobles and commoners, merchants and artisans. For religious devotions, the Polish Brothers bought a house on the south side of the Mittelburggraben, presumably the building Mittelburggraben 3. Although the magistrate said it would do everything possible to encourage the Duke to accept them in the country, they had to after a mandate from the young Duke Christian Albrecht left the city in 1663 after 18 months. Especially the Lutheran court chaplain John Reinboth had spoken out against the Polish brothers. Many then went to Amsterdam in the Netherlands or looked for admission in Lübeck, Bremen and Mannheim.

Quaker

The Friedrichstadt Quakers formed one of the oldest communities in Germany today. The beginning of the Quaker community in Friedrichstadt, which at that time was still outside the German borders, is dated to 1663. The members of the Friedrichstadt Quakers were relatively wealthy and were mainly recruited from the local Mennonites, but also from the Remonstrants and Lutherans. However, the conversational efforts of Quaker missionaries led in 1670 to a dispute between Mennonites and Quakers at times. In August 1673, the Lutheran pastor Friedrich Fabricius asked Duke Christian Albrecht to expel the Quakers, which, despite the advocacy of the city council, led to a ducal edict of deportation against the Friedrichstadt Quakers. However, the edict was repeatedly postponed and ultimately not enforced, so that the Quaker community could continue to exist. At the suggestion of William Penn , who was temporarily present in the city, the Quaker prayer house in Westerhafenstrasse was finally built from 1677 to 1678. Prominent visitors there were Peter the Great and George Fox . In order to investigate information about the construction of a possible Quaker church in his territory, the Danish King Frederick IV sent the local clerk Henning Reventlow to visit the city in the autumn of 1678, which, however, remained without consequences. In terms of the number of members, however, the congregation lagged behind those of the other religious communities in Friedrichstadt. In 1727, the community was finally dissolved due to declining memberships. The prayer house was destroyed in the First Schleswig War when the city was bombed in 1850.

Religious separatists

Especially in the 18th century, Friedrichstadt became a refuge for several religious separatists. Among them was the Danish accountant Oliger Paulli , who appeared in Friedrichstadt in 1704 as the founder of an apostolic congregation for the unification of Jews and Christians . Paulli later returned to Copenhagen via Altona , where he died in 1714.

The radical Pietist Otto Lorenzen Strandinger lived in the city between 1709 and 1715 . Strandinger had previously been a Lutheran pastor on Pellworm and in Flensburg. In 1715, Strandinger moved on to Altona, where he found accommodation with the preacher of the Pietist-Mennonite Dompelaars Jakob Denner .

After 1700 the brothers Georg and Andreas Jakob Henneberg , who came from Alfeld , settled in the city. Georg Henneberg came from the circle around Ernst Christoph Hochmann von Hochenau . Both held religious convents in the city.

The spiritualist Johann Otto Glüsing, who fled from Copenhagen to Friedrichstadt in 1707, should also be mentioned . Although Glüsing moved further to Altona in the same year, he was important as a supervisor for a small community of Gichtelians in Friedrichstadt. The Gichtelians (also called Angel Brothers) were a spiritualistic group that went back to the German-Dutch mystic Johann Georg Gichtel .

The Flemish quietist Antoinette Bourignon also had connections to Friedrichstadt, where her secretary and printer Ewoldt de Lindt acquired a house on the Mittelburgwall as a possible Quietist parish hall.

The Danish merchant Jonas Jensen Trellund (also Johann Thamsen) from Ribe was also connected to Friedrichstadt . The Lutheran Trellund caused a sensation when he healed citizens with prayers in Husum in 1680. After getting into trouble with the authorities, he moved to Friedrichstadt, where he died before 1683.

In the autumn of 1734, the Danish King Christian VI. that a group of about eighty pietist separatists from Sweden (Swedish separatists) could settle in either Fredericia, Friedrichstadt or Altona. However, the Swedish separatists only stayed in Friedrichstadt from 1735 to spring 1737 and then moved on to Altona.

Other religious communities

In the 1620s there were also attempts by Frederick III to establish trade relations in the Mediterranean and to interest Reformed Huguenots from Languedoc and Switzerland in settling in Friedrichstadt. Although there was no French Reformed church planting in Friedrichstadt (unlike in Fredericia and Altona), there were several settlers of French origin in the city. In the autumn of 1624 Simon Goulart preached several times in the Remonstrant church, also in French.

In 1735 two representatives of the Moravian Brothers visited Tønder as well as Husum and Friedrichstadt to explore the possibility of settlement. Here they also came into contact with the pietistic “Bordelumer Rotte” . In 1736 they conducted fruitless negotiations about a settlement in Bottschlotter Koog, which belongs to Fahretoft . All efforts to settle in Friedrichstadt or in the Schleswig region failed.

The Jehovah's Witnesses settled in Friedrichstadt during the Weimar Republic and the time of National Socialism; however, the community did not survive the National Socialist persecution.

Mormons lived in the city from the 1920s until the 1950s before their tracks are lost.

politics

The city had a full-time mayor until 1970 and again since 1992. With the dissolution of the Friedrichstadt office as part of Schleswig-Holstein's administrative structural reform on January 1, 2008, the city did not join the new North Sea-Treene office , but has since formed an administrative partnership with this office, which manages the city's administrative business.

In federal elections the city belongs to constituency 2 Nordfriesland - Dithmarschen Nord , directly elected MP is Ingbert Liebing (CDU). In the general election , however, the city voted in contrast to the constituency. This saw the CDU with 41.6 percent ahead of the SPD with 36.2 percent, while in Friedrichstadt the SPD beat the CDU with 568 to 467 votes. In state elections it belongs to constituency 3 Husum-Eiderstedt . The elected MP for 2005 is Ursula Sassen (CDU). Husum-Eiderstedt is also the constituency of the only Frisian member of parliament, Lars Harms (SSW).

City council

In the election for the city council on May 6, 2018, the constituency FBV and the SPD each won four, the CDU three and the SSW two seats.

coat of arms

Blazon : "In red, two silver-lined, oblique blue wavy bars, covered with the silver Holstein nettle leaf covered with a small plate divided by silver and red."

The Friedrichstadt coat of arms was approved in 1652 and depicts the two rivers Treene and Eider, overlaid by the nettle leaf of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf . The silver lines around the rivers were added in 1986 to comply with the rules of heraldic coloring .

flag

Blazon : “On white flag cloth bordered by a red stripe at the top and bottom, the city coat of arms in tinging appropriate for the flag, shifted slightly towards the pole.” The flag was approved in 1986.

Culture and sights

Architecture and cityscape

The list of cultural monuments in Friedrichstadt includes the cultural monuments entered in the list of monuments of Schleswig-Holstein.

The approximately 17 hectare large planned city is designed using a checkerboard pattern. The older part of the city, characterized by the Dutch brick Renaissance, is crossed by two canals. The Fürstenburggraben is located in the southern half of the city, the Mittelburggraben (also: Mittelburgwall) separates the southern front city with square parcels from the northern rear city with rectangular parcels.

Four bridges lead over the central moat. The market square is located directly on Mittelburggraben, the most important shopping street is Prinzenstrasse, designed as a pedestrian zone, which leads from the Fürstenburggraben to the market square.

Another canal, the Norderburggracht, was filled in as early as 1705. While life took place in the core city up to the Second World War , which was planned from the beginning for more residents than ever lived in Friedrichstadt, the admission of the displaced from the former German eastern areas made growth necessary after 1945. New quarters emerged in a fan shape in the east of the city and show the typical image of the new buildings of those years. An industrial park was set up west of the Marschbahn.

The houses from the founding days of the city are built by Dutch builders using building materials imported from Holland. Although van den Hove built a brick factory in the city as early as 1622, it was unable to meet the demand. In addition to the mops - Dutch bricks , smaller than the usual German ones - finished sandstone gables , pillars for the chimneys, yellow and green tiles and even boards were imported from the Netherlands . Other wood used for construction came from the Hüttener mountains (oak) and Norway ( pine ).

The striking feature of many buildings are the house brands or Gevelstene, often colored aggregate reliefs above the entrance door, which give an indication of the former builders or residents and often originate from the time the city was founded. The house brands of many houses that were destroyed in 1850 have been retained and now adorn the new building. The oldest house brand shows a dove with an olive branch and dates from 1622. On the other hand, house owners still put new brands on buildings that were previously unadorned.

House brands : Frosch (meaning unknown; on the market)

Trippen (coat of arms of the priestly family Laman-Trip; Prinzessstraße)

Post horn and monogram of the Danish King Friedrich VI. (Am Mittelburgwall 32)

Marketplace

On the west side of the market square there are nine stepped gables made of brick, which were created during the founding period of the city and today form the largest coherent ensemble of buildings from the founding phase of the city. Like the other houses from the founding era, these are tall and narrow according to the Dutch models. The "Edamerhaus" is supposed to be reminiscent of a building in Edam and still shows angel heads made of sandstone and wall anchors. The pharmacy right next to it is the only building with an outside staircase and has served this function since the 18th century. The stepped gable dates from the 20th century.

The house next to it, at Markt 20, historically had a stepped gable, but got a flat roof in the 19th century, which seriously impaired the effect of the entire ensemble. It was not until the 1970s that it was given a stepped gable again, but this is still clearly different from the rest of the house. The “mill house” next to it once belonged to the owner of the Eidermühle and has a corresponding house brand. After decades of decline, it was not restored until the second half of the 1990s.

The buildings on the south side of the market square did not survive the cannonade of 1850.

The actual square is divided in the middle into a stone section on the west and a leafy section on the east. The two parts are separated by a row of iron bars that date back to the horse market and were originally used to tie the animals. In the middle of the market there is a small well house from 1879. The building erected by Heinrich Rohardt is decorated with four Low German sayings by the poet Klaus Groth on the subject of water.

The green part of the market is the so-called "Green Market", which Linden had already surrounded by at the beginning of the 18th century. They were probably planted around 1705 in connection with the filling of the Norderburggraben, today's Stadtfeld. The linden trees were staggered in two rows. Remodeling in the 19th century, faulty tree care and replanting destroyed the uniform appearance of the "Green Market". In 2008, a garden monument conservation concept with a care plan and a replanting concept was decided. Until the 400th anniversary of Friedrichstadt in 2021, the green market square should be a closed picture again.

Town houses

The bombardment of 1850 destroyed a large part of the historic building stock. The buildings erected afterwards usually fit in stylistically into the existing ones and result in a harmonious cityscape, but are often simpler due to the difficult economic situation at the time. However, there are also some buildings from the early days outside the market. After many houses threatened to deteriorate in the 20th century, extensive urban redevelopment in the 1970s and 1980s saved many of the buildings.

One of the largest town houses is on Ostersielzug 7. The brick renaissance building used to serve as a Remonstrant community hall. Two other important houses are located on Prinzenstrasse. The "Paludanushaus" from 1637 is a magnificent five-axis gabled house with an impressive rococo door that has had a baroque gable since 1840. Today it serves as a meeting house for the Danish community.

The "double-gabled house" built in 1624 diagonally across the street is smaller and, in the meantime with only one gable, was restored to its original state in the 1980s.

Sacred buildings and cemeteries

In contrast to most other cities, there is no church in the center of the market square. While the steeples of the Lutheran and Remonstrant churches still shape the silhouette of the city, the other sacred buildings are buildings that are no higher than their neighborhood.

The hall of the Remonstrant Church (rebuilt 1852–1854) is baroque-late-classicist on the outside, but emphasizes plain on the inside and, according to Remonstrant belief, does not contain an altar. Until around 1885, only Dutch preaching was used in it; the pastors are still predominantly Dutch. Remonstrant church services take place monthly, the language of the sermons is German, only certain parts like the Our Father are spoken in Dutch. Behind the church is the Remonstrant cemetery. Remonstrants, Mennonites, Catholics and Quakers buried their dead in the Remonstrant cemetery. The Lutherans and Jews, on the other hand, had already acquired their own cemeteries in 1631 and 1677, respectively. After a dispute over money payments for the use of the churchyard, the Mennonites also laid out their own sacred space behind the Mennonite church in 1708.

The Catholic community moved several times within Friedrichstadt until it found a place to stay in St. Knud's Church from 1854 to 2003 . After the Jesuits came to the city in 1646, services were held in the five-gabled house. In 1846 the Copenhagen architect Friedrich Hetsch built the Catholics their own church, but the ceiling of the building collapsed in 1849. In 1854 another new church followed with the St. Knud Church, which still exists today. You can still see the pews from 1760, which previously stood in a Catholic chapel, and the Christ body from 1230. Only photos are left of the six wooden apostle figures from the 17th century, which stood to the side of the nave. The neo-Gothic church without a tower was profaned in 2003.

There is also the Evangelical Lutheran St. Christophorus Church on Mittelburgwall, whose parish hall is used by Catholics today. The hall church based on the Dutch model dates from 1643 to 1649, the west tower from 1657, the baroque tower dome from 1762. The altar painting from 1675 was painted and donated by Rembrandt's pupil and long-time resident of Friedrichstadt Jürgen Ovens , court painter to Friedrich III. It shows the lamentation of Christ. The connection to the sea shows a votive ship from 1738 with the inscription “To honor the praiseworthy boatmen's guild and this church as an ornament. Anno 1738 ". The rest of the interior was changed significantly during a renovation in 1763. The church did not get its name until 1989: In memory of the numerous tourists who visit Friedrichstadt and the church, the community named it after St. Christophorus , the patron saint of travelers.

The Mennonite Church has been located in a side building of the Alte Münze since 1708 . The church is simple, without a tower and only with a simple interior. Next to the entrance there is a porch that contains, among other things, the chief's room known as the Kamertje . The Danish Lutheran congregation has shared the Mennonite Church since the end of the Second World War. Since then, the prayer room has also housed a cross and an altar, which are otherwise not common in Mennonite church rooms. In the inner courtyard of the block behind the church is the Mennonite cemetery, on which there are still numerous gravestones from the early phase of the town's history.

The former synagogue from 1845 was partially destroyed in 1938 during the Reichspogromnacht . Most of the interior was destroyed by fire, which was put out only out of concern for the surrounding residential buildings. In 1941 it was converted into a residential building. It has been used as a cultural center since an extensive restoration in 2003. While the west facade was restored to the state it was in before 1938, the north and south facades still look like a residential building. Inside there is an exhibition about the history of the Jewish community. There is no longer any evidence of the former Jewish school or the former rabbinate. The Jewish community decided to build it because the Old Synagogue from 1734 became too small due to the rapid growth of the community. The municipality had bought the oldest house in town from 1621 and rededicated it. The city's cannonade in 1850 also destroyed the Old Synagogue. From 1675 to 1734 the community met in the back house of the community elder on Prinzenstrasse.

The old Jewish cemetery from 1676 was closed in 1939 under pressure from the city administration, after which allotment gardeners used the site. Although the city council and former community leader Israel Behrend agreed to leave the gravestones tipped over and covered with earth on the graves, most of them disappeared. In 1954, the city council decided to sell the site to a building contractor. This project ultimately failed due to protests by Jewish organizations. The square has now been designed as a memorial. The newer Jewish cemetery from 1888 survived the Nazi era and is still located at the northeast corner of the Lutheran cemetery outside the original city area.

Museums

There are two museums in the city. The Museum of Friedrichstadt's History has been housed in the Old Mint since 1997 . It not only allows a look into the neighboring Mennonite prayer room, but also shows artifacts from the city's history and its multi-religious character. The changing exhibitions also show pictures by local artists.

The Jacob Hansen Carpentry Museum mainly consists of the former workshop of the master carpenter Jacob Hansen, which has been preserved in the state between the two world wars. Hansen himself led it in this state for thirty years until he died in 1999 at the age of 92. During this time he mainly restored old furniture and, due to lack of space, neither bought new tools nor did he separate them. After the conversion to a museum, a restorer now works there.

languages

Friedrichstadt is historically located on the border between Low German (in Dithmarschen and Stapelholm ), Danish (in the Goesharden ) and North Frisian (in Eiderstedt ) language areas.

High German is the main language spoken in Friedrichstadt today. Low German is spoken by many, especially older people, and has recently been gaining increasing popularity among younger people. Danish is also spoken, especially of course by citizens of the Danish minority.

There are still some relics of the Dutch language . Some Dutch terms have survived in local usage. A lard pastry eaten here especially on New Year's Eve is called fudjes . Meatballs ( meatballs ) are known as Frika n dellen (ndl. Frikandel ).

Sports

The gyms of the secondary school and the elementary and secondary school, two soccer fields, an open-air swimming pool and Treene and Eider are used by various clubs for their fields of activity, e.g. B.

- the rifle guild from 1690, the oldest still existing club in the city. It organizes the shooting festival that takes place every three years.

- the equestrian guilds (ring rider guild from 1812; young ring rider guild from 1947), which pursue the regional sport of ring riding .

- the Friedrichstadt Sailing Club, which has been hosting an optimist training camp since 1971 , where up to 100 children and young people from Schleswig-Holstein learn and train to sail.

- the Friedrichstadt rowing society from 1926 with almost 200 members, which was able to provide German champions, world champions and medalists, especially in the junior and senior classes. The greatest success so far was the 6th place at the 2012 Olympic Games in London by Lars Hartig in the lightweight double scull.

The rowing society has held a dragon boat race every year since 2005 . The focus is on having fun. The proceeds will go to the rowing society's youth work.

Opportunities for unorganized recreational sports are primarily offered by the watercourses in the city area and the Treene. In addition to numerous privately owned boats, a rental company offers pedal boats, row boats and electric boats. With these you can drive through the city, but also up the Treene. No sport boat license is required for trips off the Eider.

The Landes-Kanu-Verband Schleswig-Holstein classifies the Treene as the main canoe waters. This is a recognition of the fact that on peak days (Ascension Day, Pentecost) there are between 200 and 300 boats on the navigable 71 kilometers of the water from Friedrichstadt. These include a comparatively large number of inexperienced canoeists who rent a boat from rental companies along the river or in Friedrichstadt.

Sailing and motor boats can go on the Eider or Treene. On the Treene, the area for sailing boats is only five kilometers to Schwabstedt , as a low bridge prevents further travel there. Motorboats can travel another five kilometers to the bridge to Süderhöft , from there they are banned from driving.

Regular events

- Lantern festival on the last weekend in July. It stands out from other events of the same kind through the lantern parade on the canals. Various imaginatively decorated boats apply to be awarded by a jury.

- Annually in July: Friedrichstadt's dragon boat festival of the rowing society and a family promenade

Economy and Transport

Economic history

In the following, shipbuilding and salt works are considered as examples of the development and decline of the economy. There were also a few other larger businesses such as a mustard factory, an acid factory and a bone meal factory, as well as various tanneries and ironers.

Presumably there was already shipbuilding in Friedrichstadt around 1624 , as the city was exempted from an ordinance that year that only allowed the sale of ships outside the country after fourteen years of use.

In 1636, the excavation of an outer harbor was completed, the area is now separated from the town center by the federal road 202. On November 23, 1637, the shipyard owner Cornelis Cornelissen applied for permission to relocate his shipyard to the outer dike so that he could build larger ships. He was the first shipyard owner there. That the shipyard in Friedrichstadt was of greater importance can also be concluded from the regrets of the people from Tönningen , who had good income from concentrated shipping over the Eider and North Sea, but had to find out: ... but no ships are built here, and even foreign vehicles are more often taken from here (Tönning) to Friedrichstadt to be repaired there .

The Napoleonic Wars led to a decline in shipbuilding, especially because the continental barrier was built in 1806 , which brought all shipping traffic in the North Sea to a standstill. At that time there were four shipyards in Friedrichstadt. In 1848 the shipyards were destroyed in the war. At least one shipyard was then to relocate, which finally closed its doors in 1912 after multiple changes of owner. This Schöning shipyard (after the last owner) built ships up to 25 meters in length and with up to three masts.

The salt works , which refined raw salt into fine salt , can already be identified shortly after the city was founded, but it was quickly abandoned due to conflicting privileges. In 1827 the salt works became profitable again, which in the meantime had been blocked by long-term supply contracts. After Nicolaus Jacob Stuhr set up the first boiler house in 1928, a total of three companies were finally established in Friedrichstadt. Stuhr was celebrated as the founder of the salt boiling trade in Schleswig-Holstein, but the government saw itself being deprived of revenue from the tariffs for the import of fine salt, so that in 1939 the tariff laws were changed. The tariff became the same for all types of salt, making this trade unprofitable again.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the various railway connections enabled a small industrial landscape with a sulfuric acid factory, a bone mill, the Kölln roller mill, the Günthrat mustard factory and the Schöning shipyard. However, this industry either moved away before the Second World War or went bankrupt, so that there was no lasting upswing. Only the Kölln roller mill, later renamed Eidermühle, was able to last longer and was the city's largest employer until the beginning of the 21st century. However, since the plant was unable to deliver the desired quantities even at full capacity, the company moved to a larger building in Elmshorn near Hamburg on the Elbe. The Eidermühle was completely demolished in 2012.

The railway connection established in 1905 to Schleswig through the Schleswig District Railway was shut down in 1934.

Economy today

Tourism is the main industry for the city, which, according to the taz, offers " a dozen photo opportunities " on every meter . It is particularly interesting for day-trippers. In 1996, for example, 300,000 to 400,000 day-trippers came to the city, often on the nearby North Sea coast spent a longer vacation. Canal rides from two providers are just as popular in this area as the miniature railway system called "Modellbahn-Zauber" , which is distributed over 100 m² . Due to their size, both are to be mentioned as private economic factors in the tourism sector. The city itself offers daily city tours between July and September, some of which are led by guides in clothes that are based on Dutch traditional costumes .

In addition to hotels and private accommodation, Friedrichstadt offers its guests a campsite , a motorhome parking space and a youth hostel . A private plastic surgery clinic is housed in the former meeting house of the Remonstrants.

Neither the industrial sector nor agriculture shows any significant activity. As early as 1987 there were only two milk-processing companies in the city, agriculture is in the other municipalities of the Friedrichstadt district .

traffic

For a long time Friedrichstadt was best reached by water. Even today it is still possible to get to the ports on the Eider and Treene from the North Sea via the Eider and from the Baltic Sea via the Kiel Canal and the Eider.

Since 1854 you could travel in "Büttel" (today in Koldenbüttel) on the Eiderstedtquerbahn , from 1887 also close to the city via the Marschbahn to Hamburg , to Danish Tønder and from 1927 also to Westerland . From 1905 there was a rail connection to Schleswig , when the Schleswig District Railway opened a 37 km long railway line from the Schleswig State Railway Station via Wohlde and Süderstapel to Friedrichstadt on December 1 of this year and built an inner-city train station with a reception building on the corner of Brückenstraße and Am Ostersielzug. Since there was no suitable bridge structure, no connection to the march was made from there. On February 1, 1934, however, passenger traffic to and from Schleswig was discontinued, and in 1942/43 the tracks of the circular railway from Friedrichstadt to Wohlde were dismantled again after goods traffic had come to a standstill. At Friedrichstadt station, which is now classified as a stop , regional trains of the Nord-Ostsee-Bahn stop mostly every hour during the day (as of 2016).

The federal highways 5 and 202 connect the place to the German motorway network. The B 5 leads to the 25 kilometers south of the A 23 in Heide , the B 202 to the 40 kilometers east of the A 7 in Rendsburg . A bridge has been crossing the Eider near Friedrichstadt since 1916, replacing the ferry connection that had previously existed for 300 years.

bridges

In total, the city has 18 bridges over the rivers and canals. The Great Bridge is located on the market square as the most striking of the inner-city bridges, a popular motif of the so-called “painter's angle” in the city center. This natural stone bridge made of granite was probably built in 1773 with a single lane roadway and two narrow sidewalks. During a renovation in 1980/1981, the front and wing masonry was removed, the stones were numbered, the inner load-bearing parts were reinforced with concrete and reinforced concrete and the wing and front stones were rebuilt in their old form.

Three more wooden pedestrian bridges lead over the central moat , the youngest of which is the Blue Bridge, a drawbridge over the Westersielzug. Since the next bridge cannot be opened, its opening function is meanwhile of no importance for shipping . The Fürstenburggrabenbrücke, a road bridge made of bricks , leads over the Fürstenburggraben .

The Treenebrücke of Bundesstraße 202 made of prestressed concrete , which connects Friedrichstadt to the B 5 in the further course, as well as the Eider Bridge to Dithmarschen from 1916 made of steel , one of the oldest Eider bridges at all, which connects the L 156 to the B 202, are important traffic- wise. The two large arches are visible from afar in the flat landscape.

To the south outside of the urban area, in the route of the Marschbahn, is the 415 meter long Eider Bridge from 1887. The section that spans the actual course of the Eider is designed as a swing bridge with a span of 87 meters.

Public facilities

There are three schools in Friedrichstadt:

- a primary school with a support center (Schule an der Treene); from 1971 to 1985 teaching activity by Otto Beckmann

- a community school (as a branch of the Eider-Treene-Schule in Tönning)

- a Danish elementary school of the Danish School Association (Hans Helgesen Skolen) that goes up to sixth grade

Students usually go to Husum to attend a grammar school . A Danish community school in Husum and a Danish grammar school in Schleswig are available for Danish pupils.

Personalities

Honorary citizen

- Constantin von Zedlitz-Neukirch (1813–1889), Police President of Berlin (1856–1861), District President of Schleswig (1867–1868), honorary citizen since 1868

- Detlev von Bülow zu Bossee , 1907–1914 Upper President of the Prussian Province of Schleswig-Holstein, had the Eider Bridge built in Friedrichstadt, an honorary citizen since 1916

- Karl Christiansen, honorary citizen since 1994.

- Elske Laman Trip, pastor of the Remonstrant Reformed Congregation, honorary citizen since 2005.

- Karl Wilhelm Michelson (1921–2012), honorary city chronicler and significantly involved in the development of the Friedrichstadt city archive, was named a fifth honorary citizen by the city council in 2011.

sons and daughters of the town

- Benjamin Calau (1724–1785), visual artist

- Eduard Alberti (1827–1898), literary historian

- Wilhelm Mannhardt (1831–1880), folklorist, mythologist and librarian

- Peter Eggers (1845–1921), entrepreneur

- Hans Holtorf (1899–1984), artist

- Norbert Masur (1901–1971), negotiator for the World Jewish Congress

Connected with Friedrichstadt

- Jürgen Ovens (* 1623 in Tönning ; † 1678 in Friedrichstadt), Rembrandt pupil and court painter to the dukes of Schleswig-Holstein-Gottorf, lived here and is buried in the St. Christophorus Church.

- Ludwig Philipp I (* 1773 in Paris ; † 1850 in Claremont House ), lived for a few months in 1796 on the run from the French Revolution and worked under an alias as a tutor.

- Christian Feddersen (* 1786 in Wester-Schnatebüll , † 1874 in Friedrichstadt), Protestant pastor and founder of the "Frisian Movement".

- Johann Christoph Biernatzki (* 1795 in Elmshorn; † 1840 in Friedrichstadt), Evangelical Lutheran pastor and writer, from 1825 to 1840 pastor at the St. Christophorus Church

- Karl Christian Tadey (* 1802 in Schleswig; † 1841 in Friedrichstadt), Evangelical Lutheran pastor and educator, from 1827 to 1841 rector of the city school, 1841 pastor at the St. Christophorus Church.

- Johannes Mensinga (* 1809 in Utrecht ; † 1898 in Flensburg ), pastor and architect, built the new Remonstrantenkirche in Friedrichstadt from 1852–1854.

- Hjalmar Schacht (* 1877 in Tinglev , † 1970 in Munich ), German politician, banker, Reichsbank President and Reich Economics Minister, his grandparents lived here.

Photo gallery development on the west side of the market

literature

- Sem Christian Sutter: Friedrichstadt an der Eider: Place of an early experience of religious tolerance, 1621–1727 . 84. Bulletin of the Society for Friedrichstädter Stadtgeschichte . Friedrichstadt 2012 (Diss. Chicago 1982).

- Manfred Jessen-Klingenberg : Justification, Proof and Failure of Tolerance. Friedrichstadts place in the history of Schleswig-Holstein. In: Nordfriesland 114 (1996), pp. 9-13. Reprinted in: Viewpoints on the recent history of Schleswig-Holstein. Malente 1998, ISBN 3-933862-25-4 , pp. 177-182.

- Herbert Karting: Sails from the Eider: The history of the Schöning shipyard in Friedrichstadt and the ships built there . Hauschild Verlag , Bremen 1995, ISBN 3-929902-35-4 .

- Jürgen Lafrenz: Friedrichstadt. In: German City Atlas. Volume 2, 3rd part. Dortmund / Altenbeken 1979, ISBN 3-89115-314-7 .

- Margita Marion Meyer, Mathias Hopp: The “Green Mark” in Friedrichstadt - To regain an urban garden monument or why it is so important to measure old trees exactly. In: Monument. Journal for Monument Preservation in Schleswig-Holstein. 16/2009, ISSN 0946-4549 , pp. 87-95.

- Dorothea Parak: Jews in Friedrichstadt on the Eider. Small town life in the 19th century. Wachholtz, Neumünster 2010 (Time + History, Volume 12), ISBN 978-3-529-06132-5 .

- Ferdinand Pont: Friedrichstadt an der Eider - First part. (PDF; 5.2 MB) 1913 and part two. (PDF; 67.8 MB), 1921.

- Marie Elisabeth Rehn: Jews in Friedrichstadt. The minutes of the board of directors of an Israelite community in the Duchy of Schleswig 1802-1860 . Hartung-Gorre, Konstanz 2001, ISBN 3-89649-646-8 .

- Willi Friedrich Schnoor: The legal organization of religious tolerance in Friedrichstadt in the period from 1621-1727. Dissertation, Kiel 1976.

- Christiane Thomsen: Friedrichstadt. A historical city companion. Boyens, Heide 2001, ISBN 3-8042-1010-4 .

- Heinz Zilch, Christiane Thomsen: The Friedrichstadt house brands . Ed .: Society for Friedrichstädter Stadtgeschichte (= newsletter of the Society for Friedrichstädter Stadtgeschichte . No. 78 ). 2009, ISSN 1617-4127 .

- Novels about city history

- Ferdinand Pont: We wanted to. (PDF; 7.3 MB) Novel about the Remonstrants in Friedrichstadt, 1921.

Web links

- City of Friedrichstadt

- Society for Friedrichstadt City History

- Ralf Bei der Kellen: Friedrichstadt in Schleswig-Holstein - religious coexistence for 400 years. In: Deutschlandfunk-Kultur broadcast “Religions”. August 18, 2019 ( mp3 audio , 6 MB, 6:32 minutes).

Individual evidence

- ↑ North Statistics Office - Population of the municipalities in Schleswig-Holstein 4th quarter 2019 (XLSX file) (update based on the 2011 census) ( help on this ).

- ↑ Patricia Wagner: Changing of the guard in Friedrichstadt - CDU woman moves into the town hall

- ↑ Schleswig-Holstein topography. Vol. 3: Ellerbek - Groß Rönnau . 1st edition Flying-Kiwi-Verl. Junge, Flensburg 2003, ISBN 978-3-926055-73-6 , p. 164 ( dnb.de [accessed on April 22, 2020]).

- ^ Johann Lorenz Mosheim , Institutes of Ecclesiastical History: ancient and modern (1832 translation by James Murdock ), p. 507; Google Books .

- ^ Bulletin of the Society for Friedrichstadt Contemporary History, No. 22

- ↑ Bernd Philipsen: … completely superfluous meeting houses. In: Gerhard Paul, Miriam Gilis-Carlebach: Menorah and swastika. Neumünster 1998.

- ↑ Bantelmann, Kuschert, Panten, Steensen: History of North Friesland. Heide 1995, p. 359ff.

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer GmbH, Stuttgart and Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 182 .

- ^ Empty benches - church near Husum desecrated , Hamburger Abendblatt, November 1, 2003.

- ^ Church in Friedrichstadt, joint newsletter, November 2010.

- ↑ a b 23rd Bulletin of the Society for Friedrichstädter Stadtgeschichte 1983, p. 144 ff.

- ↑ akens.org

- ↑ Kirkebladet for de danske menigheder i Tønning-Vestejdersted, Husum-Frederiksstad and Bredsted, dec. 2014 ( Memento from April 2, 2015 in the Internet Archive ; PDF)

- ^ Karl Michelson: Where did Stanislaus Lubieniecki live? In: Bulletin of the Society for Friedrichstädter Stadtgeschichte . 1994, ISSN 0933-3428 , p. 85-92 .

- ↑ Sem Christian Sutter: Friedrichstadt an der Eider: Place of an early experience of religious tolerance . In: Communications of the Society for Friedrichstadt City History . Society for Friedrichstadt City History, 2012, ISSN 1617-4127 , p. 121 ff .

- ↑ Sem Christian Sutter: Friedrichstadt an der Eider - place of an early experience of religious tolerance 1621-1727 . (PDF; 6.8 MB) In: Bulletin of the Society for Friedrichstädter Stadtgeschichte , 2012, p. 130, ISSN 1617-4127 .

- ^ Claus Bernet: Quaker House Friedrichstadt. In: Quakers. Journal of German Friends. Volume 77, No. 4 (July-August), 2003, p. 192.

- ^ Jürgen Beyer: A Husum prayer healer (1680/81) - from bankrupt to saint figure . In: Kieler Blätter zur Volkskunde 37 (2005), pp. 7–29; Sem Christian Sutter: Friedrichstadt an der Eider: Place of an early experience of religious tolerance . In: Communications of the Society for Friedrichstadt City History . Society for Friedrichstadt City History, 2012, ISSN 1617-4127 , p. 211 ff .

- ↑ Sem Christian Sutter: Friedrichstadt an der Eider: Place of an early experience of religious tolerance . In: Communications of the Society for Friedrichstadt City History . Society for Friedrichstadt City History, 2012, ISSN 1617-4127 , p. 66 .

- ↑ Jörn Norden: Religious communities and religious tolerance in Friedrichstadt, an overview (PDF)

- ^ Result of the city of Friedrichstadt local election 2018

- ^ Election results for the district of North Friesland

- ↑ a b Schleswig-Holstein's municipal coat of arms

- ↑ Margita Marion Meyer, Mathias Hopp: The "Green Mark" in Friedrichstadt - To reclaim an urban garden monument or why it is so important to measure old trees exactly. In: Monument. Journal for Monument Preservation in Schleswig-Holstein. 16/2009, ISSN 0946-4549 , p. 88.

- ↑ Margita Marion Meyer, Mathias Hopp: The "Green Mark" in Friedrichstadt - To reclaim an urban garden monument or why it is so important to measure old trees exactly. In: Monument. Journal for Monument Preservation in Schleswig-Holstein. 16/2009, ISSN 0946-4549 , p. 94.

- ↑ Sem Christian Sutter: Friedrichstadt an der Eider: Place of an early experience of religious tolerance . In: Communications of the Society for Friedrichstadt City History . Society for Friedrichstadt City History, 2012, ISSN 1617-4127 , p. 187/188 .

- ↑ Michael Reiter: Churches by the Sea. Lutherische Verlagsanstalt, Kiel 2000, pp. 40f.

- ^ Cemetery portrait at Alemannia Judaica , accessed April 29, 2007.

- ↑ Portrait at Museen-sh.de

- ↑ State Canoe Association "Voluntary Agreement on the NATURA-2000 Area" 12.7 Treenetal above Treia

- ^ Herbert Karting: Sails from the Eider. Verlag HM Hauschild, Bremen 1995, p. 12.

- ↑ Bulletin of the Society for Friedrichstädter Stadtgeschichte, No. 5, 1973.

- ^ Esther Geißlinger: Art should save church construction. In: Tageszeitung Nord edition, October 23, 2006

- ↑ Marschbahn stop Friedrichstadt on Bahnbilder.de

- ↑ Detailed information with drawings ( Memento of September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) at baufachinformation.de

- ^ Friedrichstadt railway bridge . Structurae.de