Reformation iconoclasm

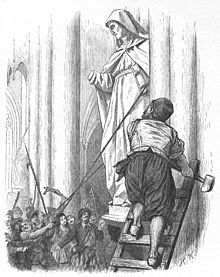

The Reformation iconoclasm was a side effect of the Reformation in the 16th century. On the instructions of theologians and the authorities who had accepted the Reformation doctrine, paintings , sculptures , church windows and other sculptures with depictions of Christ and the saints as well as other church decorations - in some cases also church organs - were removed from the churches, some sold or confiscated, destroyed or damaged.

The iconoclasm affected cities and villages across Europe, especially in the Holy Roman Empire (1522–1566) including Switzerland and the Burgundian Netherlands (1566). In addition, Scotland (1559) and England during the Civil War (1642–1649) were affected.

theology

Iconoclasm is a theological conflict within Christianity based: Although Christianity took over from Judaism , the Ten Commandments , but representations of Christ and the saints were made in late antiquity and the Middle Ages increasingly, partly in the liturgy included. Justifications for the use of images were based on the following arguments: Images served to simplify teaching of catechesis to those who did not know how to read; God had shown himself in human form through the incarnation and could be represented in this form; the admiration for the image is not for the work itself, but for what is represented.

This justification was already controversial in late antiquity. In the early days of the Orthodox Churches , there were brief periods in which the iconoclasts , who invoked the first commandment, dominated. The reformers also fundamentally rejected the creation of Christian sculptures. Reformation theology saw the liturgical use of idolatry and sensual diversion from piety. Moderate reformers in the circle of Martin Luther allowed pictures for didactic purposes; others, such as Ulrich Zwingli and Johannes Calvin , advocated a complete ban on images. In their sphere of influence, they caused the removal of all figurative representations from the interior of the church building. The Scottish Presbyterians even rejected large church buildings as expressions of human hubris .

Art history

As a result of the iconoclasm, many objects of art from the Middle Ages were irretrievably lost. The few late Gothic churches that were completed or newly created as Protestant buildings had no sculptural decoration from the start. With the construction of St. Peter's Church in Rome, the financing of which through the sale of indulgences had given a significant impetus to the Reformation, the late Gothic style in church building and Christian iconography was stylistically outdated.

etymology

The German expression "Bildersturm" has been in use since the 1530s. The Latin Middle Ages spoke of iconoclastes , yconoclastes or Middle Greek εικονοκλάστης . In the early days of the Orthodox churches, the iconoclasts were representatives of a movement that led to the Byzantine iconoclasm . In later centuries before the Reformation, iconoclastes were usually used to describe delinquents who willfully damaged Christian art; however, it was not assumed that they were heretics , but that they were seduced by demons or were in league with the devil.

From its first use around 1530, the German translation “iconoclasts” carried the connotation of a “collective, insurgent and illegal […] process” which served to spread a new faith (“iconoclasts want to preach a new faith”, Goethe). “Picture friends” and “picture enemies”, “Stürmer” and “Schirmer” were polemically opposed to one another in contemporary and later debates.

prehistory

Image theology from early Christianity to the 10th century

Justinian II (right) had an image of Christ (left) struck on a Byzantine coin for the first time (705 AD).

In Christianity, there were disputes almost from the beginning about the question of whether it was permissible to make images of Christ and the saints and to make these images part of Christian rites. The new religion was rooted in Judaism and also took over the prohibition of making images of God in the Ten Commandments . In Judaism as in Christianity, the dance around the golden calf stood for the blasphemous worship of an idol .

In addition, Christianity wanted to differentiate itself from the image-friendly Roman and Greek religions. From the 3rd to 7th centuries, however, illustrations of biblical narratives and images of saints became increasingly common. Images with biblical content first appeared as reliefs or frescoes on Roman sarcophagi , tombs and churches (the earliest documented example is the house church of Dura Europos ), were used apotropaically and finally incorporated into the liturgy like relics . The Byzantine Emperor Justinian II even had the face of Christ imprinted on coins for the first time at the beginning of the 8th century. The spreading practice was a problem for Christian theology, which responded with either total or partial condemnation ( iconoclasts ) or apologetic justification. While frescoes and, above all, glass mosaics (as in Ravenna ) became more and more popular, sculptures were held back for a long time.

Christian image theology already developed in early Christianity , which essentially revolved around the following questions:

- whether the veneration of images of Christ and the saints should be tolerated because it applies not to the images themselves but to the people embodied in them, or whether it should be forbidden as pagan idolatry

- what kind of veneration the images (if at all) may legitimately ( Latrie or Dulia )

- which iconography of God is permissible (in his human form as Christ or as the Trinity )

Early Christian Image Apologetics

A few arguments, which were formulated as early as the 4th to 8th centuries, dominated the justification of Christian image practice up to the Reformation and beyond:

- Communicative role of the pictures: The didactic justification is attributed to Pope Gregory the Great (term of office 590–604). Pictures are useful for teaching those unfamiliar with reading ( picture catechism ). Images stimulated people to devotion ( mysticism ) and supported memory (memoria). Gregor's arguments - especially the function of the picture narration as litteratura illiterato - were very widespread and later served as the most important standard arguments for advocates of pictures. (Last but not least, they relied on the auctoritas of a great doctor of the church .) Gregory's teaching was incorporated into canon law . In 1025 the Synod of Arras reaffirmed this view; it was confirmed by many authors such as Walahfrid Strabo and Honorius Augustodunensis and was even recognized by Luther. (Whether the complex medieval pictorial narratives were actually able to fulfill this didactic role in practice is a matter of dispute today; most pictorial forms were probably aimed at theologically trained recipients.)

- Reference character of the image: In early Christianity the church father Athanasius (around 298–373) defended the veneration of images of Christ with the following argument: The veneration that one brings to images of Christ does not apply to the material image, but to Christ himself. Athanasius argues with an analogy to Adoration of portraits of the Roman emperor : In late Roman times kneeling in front of the emperor's image was worth as much as kneeling in front of the emperor himself. In front of pictures of the emperor, people fell down ritually, lit incense and made intercessions; Accordingly, one could do the same in front of images of Christ, since it is not the image itself, but Christ. Thomas Aquinas later differentiated the correct way of worshiping various pictorial objects ( see section Pictorial Practice in the Middle Ages ).

- Incarnation of God: Also very early on, visual apologists invoked the justification that God had shown himself twice in human form. In his incarnation , God gave himself a human form in Jesus Christ . But that could only mean: God could be represented in his human form. The incarnation argument was put forward by the First Council of Nicaea in 325 and was effectively promoted by John of Damascus in the 8th century. Augustine in the 5th century added a further argument: God created man in his own image, which means that even after the fall of man a “similarity” (similitudo) with God remained. If one depicts man, one also depicts the divine in him.

Byzantine iconoclasm

In the 8th and 9th centuries there were serious visual theological disputes in the Byzantine upper class, which were directed against an allegedly excessive worship of images. Emperor Leo III. had a monumental statue of Christ destroyed; In the so-called Byzantine image dispute that followed, the first written image theological debate followed, in which the positions on both sides were theoretically founded. The Second Council of Nicaea in 787 confirmed the pictorial apologetics of John of Damascus as the doctrine and thus rejected the resolutions of the Council of Hiereia 33 years earlier, which had declared the divine nature to be unrepresentable.

The Synod of Frankfurt in 794 under Charlemagne tried from Western Europe to respond to the Second Council of Nicaea. Under Charlemagne, sculptures were banned as church cult images in Western Europe, with the exception of the crucifix and didactic picture narration.

In the long term, however, the image opponents were unable to assert themselves in the west or in the east of Europe: Theodora II settled the Byzantine iconoclasm in 843, thus allowing the Eastern Church to worship the icons . As early as the middle of the 10th century, the first reliquary statues were produced in Central Europe (the earliest probably in Clermont-Ferrand and Sainte-Foy ), which marked the beginning of a heyday of medieval sacred art.

Imagery in the Middle Ages

From the 10th to the 15th century, sacred art flourished in Europe with theological blessings and church support. Criticism of the pictorial practice was considered heresy ; almost all well-known theologians who commented on this question supported the use of images in churches. The rare criticism of images in the High Middle Ages was aimed specifically at the abundance of furnishings in the churches and the extravagance of the religious orders (when, for example, Bernhard von Clairvaux attacked the richly decorated Cluniac churches ), but not against the inclusion of images in religious practice.

The high medieval scholasticism developed both a complex image theory and an image-friendly theology of the image. For Thomas Aquinas , images have a relational character - they are only insofar as they are an image of something. The veneration does not apply to the sign ( signum ) itself, but to what is meant ( signatum ), i.e. the person represented. The image of Christ is therefore not worshiped as a material idol, but always as a representative of Christ. Since God has shown himself in human form in Christ, the representation of the crucified also has a part in the divine. Like the other divine persons, Christ is shown the highest form of veneration, adoration ( latrie ). The saints should be honored ( Dulia ), the special veneration of the Mother of God among the saints is called hyperdulia . Also Bonaventura argued in this direction. Thus a similar pictorial practice was theologically based in the Western Church as it had been practiced in the Eastern Church for centuries. After Thomas' death, some theologians, namely Heinrich von Gent and Durandus von St. Pourçain , criticized his apologetic conceptions, but this remained ineffective for a long time. The most notable critic of the cult practice itself was among the scholastics Petrus Abelardus , whose remarks against the Christian idol worship apparently did not circulate or were secretly shared by his opponents, at least they did not comment on it. Abelard directed himself against the illusory character of the image that man worships, as if there was a living god in it, when every other living being could see that this was not the case.

Work piety

The practice of religious devotion required the medieval man to put on a soul device , that is, to donate a substantial part of his inheritance in order to shorten his time in purgatory and to attain salvation more quickly. These foundations “administered” the church until the return of Christ. Popular foundations were altars , wall paintings or altarpieces , on which in the late Middle Ages the bourgeois donors themselves appeared alongside the saints ( donor picture ).

The Middle Ages knew a variety of Christian genres that served different religious purposes. All known materials and media - from expensive book illuminations and ivory carvings to glass painting , wood carving and wall painting to the widespread single-leaf woodcut - were used. Tales in pictures on church walls, in illumination, on reliquary shrines and other liturgical or profane objects told of the history of salvation , the biblical events, the miracles of Jesus or the Last Judgment . The type of cultic representational image , such as a lecture cross or image of grace , was used in liturgy and pilgrimages . Devotional images in the form of the Man of Sorrows , Ecce Homo or Pietà were used for private, intimate contact with Christ and the saints . In the broadest sense, all pictorial works served image catechesis in the sense of Gregory the Great: as an aid for didactic instruction of laypeople who were ignorant of the written language . For this purpose, special catechism boards with pictures of the so-called symbol of the Christian Creed , the Apostles , the Our Father , the Ten Commandments , the virtues and vices were made and hung in schools, hospitals and churches.

Worship of representations of Christ and the saints

In the cult practice of the late Middle Ages, some representations of Christ and the saints were venerated like the body of Christ in the Eucharist : They were treated as if the persons in them were actually present ( real presence ). Pictorial works met individual piety: One wanted to experience the sacred sensually, i.e. see, hear, smell and taste. Sculptures were incorporated into piety through prayers , kneeling down , candles, and votive offerings . In this way the churchgoer established a healing personal connection to the person of the saint. The setting value of many cult images was enhanced by relics were kept in it. The religious value of images of saints was also used politically; so cities had representations of their city patrons venerated by the people and thus acquired spiritual protection for their political zone of influence. Pilgrimages to supposedly miraculous images of the Virgin were not least also economically profitable - as a source of income for the clergy as well as for the hostels and restaurants in the area.

The clergy, as well as the people, were of the opinion that there was a direct communicative connection between the image and the depicted saint - whatever was added or given to it, the latter gets to feel. Damage to or theft of sacred art was punished as sacrilege on the basis of this practice . The main priority was not their material value, but rather their identification with the person of the saint himself. Iconoclasm , the vandalization of sacred works, was not infrequently an accusation that justified pogroms against Jews . Science sees one of the most difficult phenomena of the epoch to be explained in the change from the established piety practice to widespread vandalism against the revered sculptures. However, the end of the 15th century was already marked by growing religious puritanism ; in the decades before the Reformation, for example, pious foundations declined noticeably.

In recent research, doubts arise as to how deeply the cult of images was anchored in popular practice. If it was previously assumed that the cult of images was particularly popular among the uneducated classes of the population and was only tolerated by the clergy, more recent research tends to the opposite thesis: the preference for beautiful, artistic images was cultivated by wealthy and educated art lovers - the images were donated and collected - as well as the higher clergy. For example, clergymen had figures of the saints covered with thorns or nettles or thrown into the water in order to punish them (at least this practice was prohibited by the Council of Lyon in 1274). The Pope promoted pilgrimage, for example on the handkerchief of Veronica in Rome. On the other hand, there are humorous folk tales in which figures of saints are burned in the oven without punishment and referred to as "idols". The German word “Götze” (little god), first guaranteed for the year 1376, was the first to describe Christian images in a contemptuous way; it was only applied to pagan idols in the Luther Bible . It is therefore assumed today that the cult of images was viewed with more distance among the population than among the spiritual elite.

Image criticism in the 14th and 15th centuries

In Northern Europe, theological criticism of images can be recorded at the latest in the 14th century. The theological discussion of the problem of images was mainly conducted in pamphlets , sermons and biblical commentaries, seldom came into practice and was not the focus of internal church conflicts. Not the image use was considered a real problem, but to separate the difficulty of the misuse of the image from right: the useful function of the images as catechesis (in Gregory's mind) stood against " idolatry " (idolatria) , with which the superstition of the miracles individual objects and practices was meant. Several reform synods tried to regulate the cult of images in the 15th century.

The demand for the complete abolition of images was only supported by radical church reformers who also supported heretical theses. Scattered criticism of images by the scholastics Durandus de San Porciano and Robert Holcot were taken up again by the two great heretical movements of the late Middle Ages, the Lollards and the Hussites . The spiritual fathers of the movements, the English reform preacher John Wyclif (before 1330–1384) and, in his successor, the Prague university professor Jan Hus (around 1370–1415) turned against Christian visual art. They collected and bundled the scattered arguments of the theological visual criticism and included them in their doctrines, which turned against the papacy and the religious piety.

Representations of the Trinity ( mercy seat ) should be prevented according to Wyclif, since God the Father and the Holy Spirit themselves cannot be represented. It is more honorable to distribute one's riches to the poor than to adorn the churches with them. The true images of God are people. Direct worship of God is preferable to mediated worship. In England the lollards carried Wyclif's views on; In their view, figurative works did not fulfill the intended purpose of a lay Bible, but promoted idolatry in practice, because laypeople could not distinguish between the representation ( signum ) and the intended person (signatum) . Pictures are only "veyn glorie" (vain appearance).

In East Central Europe, the Hussites demanded the destruction of all sculptures, since legitimate worship cannot be distinguished from forbidden idolatry. They went down in history as violent iconoclasts.

Photo criticism of the reformers

Martin Luther commented on the question of images, but only in terms of material foundations. He considered the pros or cons of the visual discussion to be unimportant; Incorrect and correct use of the pictures could not be reliably distinguished anyway. Rather, his anger was directed against the idea that salvation could be achieved through good works , especially pious (pictorial) endowments ( Von den gute Werken , 1520). God does not expect fasting, pilgrimages and richly decorated churches, but only faith in Christ. Luther ended the iconoclasm in Wittenberg in 1522 with the invokavit sermons without electoral violence, only through the strength of his argumentation. In 1525 Luther wrote that pictures are allowed "to look at, to testify, to remember, to zeych", thus as intended by Gregor as didactic means.

After 1520, Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt, professor at the University of Wittenberg , called for the active destruction of religious sculptures for the first time during Luther's time. This was justified in Luther's sense: the goal of Christianity is to abolish poverty and begging, but this can only happen if the wealth, instead of flowing into pious foundations, directly benefits the poor. Karlstadt argued with the First Commandment of Moses, which forbids idolatry. Images have only material value, not communicative, and cannot “teach” in Gregor's sense. "Living" images of God are fellow human beings. Karlstadt's pamphlet Von abtuhung der Bylder (1522) spread throughout the German-speaking area in two editions. The begging argument was completely ignored in the reception, only the iconoclastic appeal was enthusiastically received.

Body hostile arguments are another attempt to justify the condemnation of images. According to Karlstadt, images of saints did not show the divine nature, but the fleshly appearance of the saints, which suppressed access to God in the heart; the church becomes a whore house through carnal representations. The veneration of the human, that is, carnal Christ in the image and in the sacrament should be rejected. The Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli essentially followed Karlstadt's argument. Cult images are materializations of the idols that man has in his heart and that keep him from true worship. Instead of cult images, the Christian cult should apply to the poor themselves, since God also shows himself in them (he did not, however, implement this thesis in practice). John Calvin judged even more strictly: The Ten Commandments should be obeyed, that is, the prohibition of the depiction of God and idolatry should be interpreted strictly. He equated idolatry with carnal lust; it is the carnal phantasy of man, which one must confront, since Christ also withdrew from his carnal existence through ascension . Calvin rejected Augustine's old argument that there is a certain resemblance to God in the human form: with the fall of man, man lost all resemblance to God.

Criticism of images by opponents of the Reformation

Criticism of the pictures also came from theologians loyal to the Pope who did not join the Reformation or were suspected of being involved in Reformation activities. The arguments that differ from the reformers are sometimes only gradual. The Catholic image critics, however, were not concerned with completely abolishing the overflowing and splendid images of saints and their cultic veneration, but rather with disciplining them and preventing excessive practices.

On the side of the Catholic image critics are Erasmus von Rotterdam (who witnessed the iconoclasm in Basel as an eyewitness) and Luther's opponents Thomas Murner and Hieronymus Emser ; Even with Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg and Sebastian Brant , who both died before the actual Reformation, there is already evidence critical of the cult of the image. Murner 's conjuring of fools (1512) denounces the vanity and extravagance of the creators. Geiler von Kaysersberg criticized paintings with naked female saints and Jesus children, which would only serve to arouse erotic desires. Indeed, in the 14th and 15th centuries, increasingly beautiful women in fashionable dresses appeared on religious displays.

The artistry of contemporary imagery was a key point of contention. In the Netherlands and Italy in particular, the new technique of oil painting was used for an extremely illusionistic style of painting, which was able to reproduce the materiality of beautiful fabrics, possessions and people particularly well. Art buyers who had trained their eyes on secular motifs also wanted more sumptuous, realistic images of saints. Hieronymus Emser , otherwise an energetic opponent of Luther, argued against such "artificial" (artful) pictures that missed their didactic purpose and only persuaded to admire the art of painting ("insulting art and the kind of bosses"). Simplicity (simplicitas) of representations was a common requirement forward as nachreformatorischer image theology: Images should call in more restrained style of painting the deeds of saints and activity of Christ in memory and call for imitation, but not conspicuous by their pomp and artifice. Images of saints made “hurish” and “sullen”, which were made shameless, seductive and indecent, were not considered acceptable; supposedly miraculous images; too expensive, too artistic or too many pictures are inappropriate in churches. The laity should be taught to behave with “moderation and rule” and to drive out belief in miracles; the donors should rather spend their money on the poor; painters and carvers hold back in design.

The desire for a more modest image of saints was also reflected in painting. Robert Campin and Jan van Eyck renounced the depiction of gold and precious stones as early as 1400. Campin as well as Fra Angelico depict Mary and the saints in very modest, poor rooms. The aging Sandro Botticelli , impressed by Savonarola's preaching of penance , gave up his sensual paintings of ancient pagan motifs and turned to religious painting; He burned some of his secular pictures with his own hands in 1497 on Savonarola's “ Purgatory of Vanities ”. In southern Europe, spending on religious foundations fell, while in Central Europe it flourished again around 1450, only to fall sharply in the years before the Reformation, accompanied by criticism from within the Church and general weariness of the Church's wastefulness.

Catholic visual criticism led to attempts at reform in the post-Reformation period, but these remained in the realm of theory. In 1549 , the Provincial Synod of the Diocese of Mainz passed a guideline for the appropriate church decoration, which was based on “some suitable pictures or panels (...) which contain histories that (are) properly and piously painted, without any secular, indecent or frivolous Jewelry "should restrict. In essence, however, one clung to church art insofar as it could serve religious instruction.

Iconoclasm in individual places

The iconoclasm of the Reformation did not take place simultaneously and in very different ways in all places. The most momentous iconoclasms took place in cities, especially in the free imperial cities . Religious sculptures were donated primarily by wealthy townspeople - patricians , merchants, craftsmen who had become wealthy - so there were a large number of sculptures there. Almost everywhere the newly enacted Reformation city ordinances contained a provision that was directed against sculptures in churches.

Historical sources document organized confiscations of church treasures as well as violent actions by fanatical crowds, symbolic show trials as well as individual, spontaneous acts of vandalism. In Münster, for example, the Anabaptists used the means of high jurisdiction against images , while in Constance inventory lists were used and confiscated objects were sold in favor of the city treasury. In some places the donor families were allowed to take “their” altarpieces and carvings and save them from destruction.

Iconoclastic actions were not always based on purely religious motives; At the local level, political conflicts between the people and the elites were waged through them. There was already a tradition of revolt in the cities, which in the pre-Reformation centuries had led to the development of a special urban social structure with city governments elected by the citizens. The population structure was permeable and more receptive to reformatory demands.

In many cities, especially in the south and in Switzerland, the council retained the upper hand over the progress of the reform processes; iconoclastic actions were only carried out by order. The “proper” evacuation of the churches was carried out by the city authorities so that there would be no violent riots. In this way, the council was able to channel the tensions between old and new believing groups.

In some places, sculptures were not destroyed, but confiscated with the entire church treasure and sold for a profit. Economic conflicts between the citizens and the church had a history: thanks to large estates, the clergy took advantage of the urban sales markets without giving anything back, as they benefited from tax privileges in many places. Some of the iconoclastic actions can therefore be interpreted as redistribution actions in which the church's assets should be returned to the economic cycle and the city coffers.

Some researchers even consider the iconoclasm as a whole as a revolutionary popular uprising, in which the masses, incited by charismatic preachers, revolted against the corrupt church elite.

North of the empire

| year | north | south |

|---|---|---|

| 1522 | Wittenberg , Meissen (?) | |

| 1523 | Halberstadt , Breslau (?), Danzig | Zurich , Strasbourg |

| 1524 | Nebra , Mühlhausen , Koenigsberg , Magdeburg , Zwickau | St. Gallen , Rothenburg , Waldshut |

| 1525 | Wolkenstein , Stolp , Stettin , Torgau , Stralsund | Basel |

| 1526 | Cologne , Dresden | |

| 1527 | Soest , Pirna , Goslar ( Goslar riots 1527 ) | |

| 1528 | Braunschweig , Hamburg , Goslar | Bern |

| 1529 | Minden (?), Göttingen | |

| 1530 | Einbeck | Neuchâtel |

| 1531 | Lippstadt | Ulm , Constance |

| 1532 | Herford , Lemgo , Waldeck | Geneva , Regensburg , Augsburg |

| 1533 | Höxter , Warendorf , Ahlen , Beckum | |

| 1534 | Hanover , Munster | |

| 1535-1546 | Wesel , Hildesheim , Merseburg , Alfeld | Nuremberg |

In the north, iconoclastic actions first appear in cities on the Baltic Sea , Pomerania and Saxony such as Danzig , Magdeburg and Stralsund . A second wave affects Lower Saxony and Westphalia from 1528 to 1534 . In 1582 in Bremen , Christoph Pezel ordered the demolition or removal of all sculptures from the municipal parish churches.

An example of the bitter dispute between Lutherans and Reformed people about the ban on images is the dispute over a high altar in Danzig around 1600, see Jakob Adam .

Wittenberg

In the Reformation order of the city of Wittenberg of January 24, 1522, especially formulated by Karlstadt, it says under point 13: “The pictures and altars in the church should also be removed in order to avoid idolatry, three altars without pictures should be full suffice ". In February 1522 there were tumultuous scenes in the Wittenberg town church after Karlstadt - without Martin Luther's knowledge - had published the treatise Von abtuhung der Bylder .

Luther himself condemned the destruction of images. Valuable church furnishings were preserved in his immediate area of influence , such as St. Sebald and St. Lorenz in Nuremberg or in the Wienhausen monastery . "Luther let the cult die off, but the cult objects preserved."

Switzerland

For the general historical course, see Reformation and Counter-Reformation in Switzerland .

The first iconoclasms in the south were subject to public order. Collective actions were largely prevented. Zurich became a model for many cities. In the city of Zurich, disputations took place in 1523 and 1524 on how to deal with the sculptures. At the second disputation (October 26-28, 1523), the leading priest Ulrich Zwingli pleaded for a complete abolition of the sculptures, an opinion that met with broad approval. (One of the opponents was Rudolf Koch, canon at the Grossmünster , who relied on the authority of the traditional advocates of images.) Parishes should vote on the removal of images and inform the faithful about the changeover; Founders should be able to withdraw their foundations. In June 1524 the council issued a mandate that within six months "the idols and images should be removed with breeding so that the word of God might be given in place"; the sculptures were removed behind closed doors by priests and craftsmen within thirteen days.

In Basel , Bern and St. Gallen, however, the iconoclasm was tumultuous.

South of the empire

The events in the Swiss cities found imitators in the south of the empire, especially in the imperial cities of Ulm (1531), Augsburg (1532), Regensburg (1534/1538) and Nuremberg (1542).

In the imperial cities of southern Germany there were serious interventions in the art inventory and in the building fabric of churches. On the so-called “Götzentag” in the summer of 1531, both church organs and a total of 60 altars were removed from the Ulm Minster , brought to the surrounding village churches or destroyed with brute force. A contemporary source reports on the brute force that was at work at the Götzentag: “When you were unable to lift the body with the pipes in the great organ, you tied ropes and chains around it, then stretched horses to them and through them Tear down violence at once and let it fall over a heap ”. The so-called Karg altar niche by Hans Multscher was also hacked away.

In the episcopal city of Constance , the iconoclasm was organized under the direction of the city government. In the Konstanz Minster , the then cathedral church , valuable reliquary shrines and usable art objects were confiscated by the Konstanz city treasury. This let the metallic values melt down gradually, other values were sold for profit. The relics found , including the bones of the diocese saints Konrad and Pelagius and the bones of St. Gebhard kept in the Petershausen monastery , were thrown into the Rhine . The more than 60 altars of the minster as well as almost the entire inventory were thus irretrievably lost.

England

Above: “Papists” save themselves with their “junk” on the “Ship of the Roman Church”; images of saints are burned in the background.

Bottom left: clerics receive the Bible from the hand of Elizabeth I; right: a communion table in a church room without pictures.

The first iconoclastic incidents occurred in England as early as the 1520s and 1530s. Iconoclasts infected 1522 Marie a church in Rickmansworth ( Diocese Lincoln ) fire; minor vandalisms are z. B. occupied for Worcester and Louth .

The first systematic wave of iconoclasm followed from 1536 to 1540 at the behest of King Henry VIII. Henry broke with the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church and made himself head of the Anglican Church . The principles of the European Reformation were now also implemented in England, including the demand for “temple cleansing”: he took images of grace , shrines and relics from the monasteries and pilgrimage churches and had them publicly burned in London. Heinrich had rich monasteries plundered for the benefit of the state treasury. The Bishop of London supported Henry with instructions to the parish clergy.

Edward VI. , Heinrich's successor, proceeded even more drastically. In 1547 and 1548 the Magistrate of the City of London issued a mandate on behalf of the King to remove all pictures from the city's churches - an order which the royal officials have documentedly implemented. Ornate stone altars were replaced by wooden tables. Rood screens , crucifixes , images of Mary and John, and sometimes liturgical books , were burned in public places and churchyards. The iconoclasm affected St Paul's Cathedral and many London churches, as well as churches and monasteries in the country.

In 1550, parliament decided to completely destroy all religious sculptures, with the exception of epitaphs and memorial stones. It is also recorded that in 1550 three or four shiploads of sculptures were sold in France; others ended up in Holland . Although iconoclastic actions are documented for many individual English locations, exact data on the extent of the destruction are not known.

As a reaction to the coronation of Elizabeth I , iconoclastic uprisings among the population broke out in 1559 . Rood screens and sculptures were burned. These actions no longer had any support in the institutions; the question of images was already controversial within the English Church; one was undecided whether observing the first commandment would justify the destruction of sculptures on a massive scale. Unauthorized iconoclasm was a criminal offense; the government had destroyed sculptures partially replaced. Elizabeth I contented herself with the requirement that only “improperly” used images should be removed.

A century later, iconoclasm became a means of struggle between parliament and king. The destruction that took place at the behest of Parliament in the English Civil War of the 1640s is considered to be even more profound than that carried out on behalf of the king in the 16th century.

Netherlands

The beginning of the picture criticism in the 16th century

The iconoclasm in the second half of the 16th century is closely connected with the spread of Calvinism in the Netherlands and France and is characterized by a close connection between the destruction of images and the political and religious conflicts in the civil war. At first it differed little from the iconoclastic processes in Switzerland and Germany with regard to the context of the arguments relating to the question of images, the objects of destruction and the question of the correct approach. This iconoclastic wave received a new component through an increased number of writings, which renewed and further developed the criticism of the cult of images and of Catholic worship. These include, for example, the writings of Pierre Viret, John Hopper and Johannes Anastasius Veluanus, which took up and expanded upon Calvin's criticisms of the question of images. In addition, attempts were made to bring the illiterate closer to the criticism of pictures through plays, sermons and poems. In the Netherlands it was above all the rhetoric chambers, in France the songs and poems that spread criticism of the cult of images and called for iconoclastic acts.

Iconoclasts have been systematically persecuted and punished as heretics in the Netherlands since the 1520s. In an edict in 1522, the royal government of the Netherlands threatened severe penalties for those who destroy pictures that had been made in honor of God, the Virgin Mary or the saints. The persecution of the new believers as heretics led them to flee to England, France and the empire. There they came together to form groups of refugees. Over time, these came under Zwinglian-Calvinist influence and trained preachers. After the signing of the Compromise of the Nobles and the Edict of Margaret of Parma, which ordered moderation in the persecution of heretics, the trained preachers and lay preachers returned to the Netherlands and began to preach publicly.

The hedge sermons

In the Netherlands, the iconoclastic activities of 1566 were preceded by so-called fence sermons ( hedge sermons ). The first fence sermons in Flanders were not initiated by the Calvinist consistories, but were spontaneous, nocturnal church services. They were led, on the one hand, by clergymen who strived for reforms but were formally not Calvinists, and on the other hand, by Calvinist theologians and members of local rhetoric schools. Examples are the monks Carolus Daneel and Antonius Alogoet. Both of them left their monasteries overnight and began preaching in the area. The consistory in Antwerp took up the reported incidents in a synod in May and June and now decided to publicly assemble the Calvinist community again and to hold public sermons. Many of the preachers came back to the Netherlands from the exile congregations in France, England and the Empire. The fence sermons began in the metropolitan areas of West Flanders, where many traders already sympathized with the Calvinist faith, quickly spread across the entire Dutch provinces and became a mass event. It is estimated that 7,000 to 14,000 people attended individual sermons.

The spread of the iconoclasm in 1566

The spread of iconoclastic activities in the Netherlands began in August 1566 in the vicinity of Steenvoorde, near the French border, where the first fence sermons had also taken place. After the Calvinist priest Sebastien Matte had preached in the city on August 9, the congregation broke into a chapel in Steenvoordes on August 10 and looted it. In the next few days, under the leadership of the two priests Matte and Jacques de Buzère, further church looting took place in the vicinity. On August 15th the same group of iconoclasts reached Ypres . Bishop Martin Rythovius tried in advance to persuade Duke Egmont, the governor of the province, to remain in the city in order to avoid looting the churches; however, he left at noon on August 14th. On August 16, all monasteries and churches in and around Ypres, including the pilgrim church in Beveren, were cleared.

Subsequently, on August 18, Oudenaarde and on August 20, Antwerp were struck by iconoclasms. A few days before the riots in Antwerp, Hermann Moded , one of the city's Calvinist priests, preached against idolatry. On August 19, some young people broke into the church in Antwerp and mocked a statue of the Virgin that had been taken through the streets a few days earlier in a procession to the Assumption of Mary. The next day, citizens again entered the church and began looting and clearing it. They sang psalms, drank the mass of wine and smeared their shoes with blessed oil. On August 21, Hermann Moded preached in the same church. Over the next two days, 20 to 30 male youths and men looted and destroyed the facilities of thirty other churches.

In Ghent on August 22nd, under the leadership of Lievyn Onghena, the regent was presented with a forged letter from Duke Egmont, which not only allowed the destruction of the pictures, but also demanded a guard for those who carried out the work. Both applications were granted by the Ghent magistrate. On the night of August 22nd to 23rd, there was consequently an iconoclasm in the city. When the executors were asked to leave the next morning, the facilities of seven parish churches, one collegiate church, 25 monasteries, ten poor houses and seven chapels were destroyed. The iconoclasts left the city in three directions and in the next few days began to free the churches in the surrounding communities from the images. Iconoclasm took place in Tournai on August 23 and in Valencienes on August 24. Both cities had mostly Calvinist councils that supported the work of the iconoclasts.

In the northern territories of the Netherlands, with the exception of Zeeland and Utrecht, the iconoclastic processes were quieter. On August 21 and 22, the pictures were carefully removed from the churches in Middelburg under the supervision of the church council and brought to the town hall. In Amsterdam the mood among the population was so charged that, although the pictures had already been removed from the churches, there was unrest after the news of the events in Antwerp reached the city. Delft was ravaged by iconoclasts on August 24th and 25th, and iconoclasts removed the images from the churches in The Hague on August 25th. At the same time the pictures were removed from the parish church and the monasteries of Utrecht under professional guidance; however, the five main churches of the city remained untouched. The same men who appeared in The Hague, Delft and Utrecht also worked in the area around Culemburg.

Characteristic of some iconoclasms in September is the presence and approval of nobles on whose territories the cleared churches stood. Duke Floris was present at the evacuation of two parish churches in Culemburg; in Asperen it was two sons of noblemen who oversaw the iconoclastic activities; In Vianen Duke Brederode ordered the removal of the pictures from the churches on September 25th and Willem van Zylen van Nijevelt destroyed his own family chapel in Aartberghen. In the same month there were iconoclasts in Leeuwarden, Groningen, Loppersum, Bedum and Winsum.

1581 - The iconoclasm breaks out again in Antwerp. Other works of art in the Cathedral of Our Lady were destroyed.

Transylvania

A key figure of the Reformation in the now central Romania situated region Transylvania was the printer and humanist John Honterus (around 1498-1549) from Kronstadt . In October 1542, the Protestant mass rite was introduced in Kronstadt. In 1543 the Reformation was introduced in Kronstadt and the surrounding Burzenland on the basis of Honterus' writing Reformatio ecclesiae Coronensis ac totius Barcensis provinciae . From there, the Lutheran Reformation spread among the Transylvanian Saxons . In the spring of 1544 the side altars and images of saints were removed from the Black Church . In 1547, the church ordinance of all Germans in Sybembürgen , based on Honterus' Reformation pamphlet, was available in printed form, which introduced the Reformation for all German residents of Transylvania. In June 1572 put one in the Margarethenkirche of Medias gathered total synode the Augsburg Confession , a binding basis as the Church design of the Saxons.

The earliest known document on the removal of pictures and sculptures from the churches comes from the Bistritz council clerk Christian Pomarius. In 1543 he wrote that the Turkish threat was near and that the Turks would kill the worshipers first. In 1544 the organist of the Black Church and Kronstadt city chronicler Hieronimus Ostermayer reported:

“With the will of the authorities, the pictures from the churches, including the large altar in the parish church, have been demolished. Ditto on April 22nd with the common choice of the learned and God-fearing man Mr. Johannes Honterus as the parish priest in Cronstadt. "

As early as the 1550s, however, the opinion gained acceptance that pictorial representations of religious subjects could be preserved as works of art and therefore do not have to be removed. In 1557 the Synod of Sibiu declared that images with biblical or church history should be preserved. In 1565 the Synod of Sibiu declared:

“ Sufficiat tibi in altari tuo salvatori in cruce pendentis imago, quae passionem suam tibi representat. "

"It is enough for you in your altar to have an image of the Savior on the cross, through which he represents his passion."

From the pre-Reformation period, the main altars of the churches in Transylvania, often large winged altars , such as the Medias or Biertan altar , have been preserved . The existing panel paintings were mostly redesigned in line with the Reformed faith. In contrast, figurative representations, especially from the central shrines of the altars, have been removed throughout.

Wall paintings and frescoes were whitewashed in the Protestant churches of Transylvania and only rediscovered and exposed during restoration work in the 1970s, for example in the Margarethenkirche in Mediasch . The wall paintings were only preserved intact in the areas that were not on the royal soil , which was endowed with traditional autonomy rights and where the population was therefore not allowed to freely choose their denomination, for example in the fortified church of Malmkrog .

Consequences of the iconoclasm

The Council of Trent , which in the Decretum de invocatione, veneratione et reliquiis sanctorum, et sacris imaginibus of December 3, 1563 expressed that “the images of Christ, the Virgin Mother of God and the other saints who are especially in the churches and must remain, the owed respect and reverence is to be shown ", nevertheless stipulated in the same resolution that the worship of the images may not be as if" there was a deity in them or a force because of which one had to show them honor, or as one may place one's trust in images, as it otherwise happened from the pagans, but because the honor relates to the archetypes that they present. ”The council heralded the age of the Counter-Reformation in the Catholic regions . The architecture and furnishings of the baroque church buildings implement this claim.

In the Reformed and Lutheran churches, orders for religious sculptures declined sharply in the 16th century. Church construction also stagnated during the turmoil of the Reformation, in some cases for centuries. In northern Germany, written altars took the place of medieval sculptures in the 16th and 17th centuries . Often one reads there the five main parts of the Christian catechism, so above all the ten commandments , the creed , the Our Father and the institution of baptism and the Lord's Supper . After the iconoclastic phase, the images returned to the Lutheran churches in the 17th century in the form of elaborate, baroque altarpieces . The altars by Ludwig Münstermann in the county of Oldenburg are well known. The reformed churches remained without images. In many places, the Counter-Reformation completed what the iconoclasm had begun: the “artless” medieval sculptures were whitewashed or gave way to new, magnificent altars, stucco ceilings and wall paintings.

See also

literature

- Milena Bartlová: The iconoclasm of the Bohemian Hussites. A new look at a radical medieval gesture . In: Wiener Jahrbuch für Kunstgeschichte . 59 (2011). ISBN 978-3-205-78674-0 . Pages 27–48. Digital version (PDF)

- Peter Blickle u. a. (Ed.): Power and powerlessness of images. Reformation iconoclasm in the context of European history. Oldenbourg, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-486-56634-2 .

- Horst Bredekamp : Art as a Medium of Social Conflict. Image battles from late antiquity to the Hussite revolution (= Edition Suhrkamp , volume 763). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1975, ISBN 3-518-00763-7 , (Dissertation University of Marburg, Department of Modern German Literature and Art History, 1974, 405 pages, 34 illustrations, under the title: Art as a medium of social conflicts, image fights between 300 and 1430 ).

- Dietrich Diederichs-Gottschalk : The Protestant written altars of the 16th and 17th centuries in northwest Germany. An examination of the history of churches and art into a special form of liturgical furnishings in the epoch of confessionalization. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1762-7 ( Adiaphora 4), (Simultaneously: Göttingen, Univ., Diss., 2004: The Protestant written altars of the 16th and 17th centuries in northwest Germany in the county of East Friesland and in Harlingerland, in the ore monastery and in the city of Bremen as well as the territories of the city of Bremen, with an excursion each to the county of Oldenburg and the Principality of Lüneburg ).

- Cécile Dupeux, Peter Jezler , Jean Wirth (eds.): Iconoclasm. Madness or God's will? Fink, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-7705-3544-8 .

- Helmut Feld: The Iconoclasm of the West. Brill Academic Pub, Leiden u. a. 1990, ISBN 90-04-09243-9 ( Studies in the History of Christian Thought 41).

- Johannes Göhler: ways of faith. Contributions to a church history of the country between the Elbe and Weser. Landscape Association of the Former Duchies of Bremen and Verden, Stade 2006, ISBN 3-931879-26-7 ( Series of publications of the Landscape Association of the Former Duchies of Bremen and Verden 27).

- Reinhard Hoeps (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Bildtheologie. Volume 1: Image Conflicts. Schoeningh, Paderborn 2007, ISBN 978-3-506-75736-4 .

- Gudrun Litz: The Reformation image question in the Swabian imperial cities. Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-16-149124-5 ( Late Middle Ages and Reformation NR 35).

- Karl Möseneder (ed.): Dispute over pictures. From Byzantium to Duchamp. Reimer, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-496-01169-6 .

- Norbert Schnitzler: Iconoclasm - Iconoclasm. Theological picture controversy and iconoclastic action during the 15th and 16th centuries. Fink, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-7705-3052-7 (also: Bielefeld, Univ., Diss., 1994).

- Robert W. Scribner (Ed.): Pictures and iconoclasm in the late Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1990, ISBN 3-447-03037-2 ( Wolfenbütteler Forschungen 46).

- Lee Palmer Change: Voracious Idols and Violent Hands. Iconoclasm in Reformation Zurich, Strasbourg, and Basel. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1995, ISBN 0-521-47222-9 .

- Susanne Wegmann: The visible faith. The picture in the Lutheran churches of the 16th century . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2016, ISBN 978-3-16-154665-5 .

Iconoclasm in literature

- Saint Cecilia or the violence of music (a legend). 2nd version. In: Heinrich von Kleist . Erzählungen, Vol. 2, 1811, pp. 133-162.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ The leaflet draws attention to the fact that the images are not responsible for turning them into idols; Right in the picture: A man with a sting in his eye looks at the iconoclasm. (Uwe Fleckner, Martin Warnke, Hendrik Ziegler (Hrsg.): Handbook of political iconography , Volume 1, p. 145, ISBN 978-3-406-57765-9 ) ( online ).

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 33

- ↑ Iconoclasts. In: Jacob Grimm , Wilhelm Grimm (Hrsg.): German dictionary . tape 2 : Beer murderer – D - (II). S. Hirzel, Leipzig 1860 ( woerterbuchnetz.de ).

- ^ 2 Mos. 20.3-4; 5th Mos. 4.25ff., 27.5

- ^ Letter from Gregory the Great to Bishop Serenus of Marseille, PL 77, left. XI, indict. IV, epist. XIII, sp. 1128C; ep. 9; ep. 11; ep. 105 MPL 77, 1027f.

- ↑ Decretum magistri Gratiani, Decreti tertia pars de consecratione dist. III, c. 27; in: Aemilius Friedberg (Ed.): Corpus Iuris Canonici I , Graz 1959.

- ↑ Walahfrid Strabo: De exordiis et incrementis rerum ecclesiasticarum.

- ^ Honorius Augustodunensis: Gemma animae.

- ↑ Scribner 1990, p. 12

- ↑ Jean Wirth: The denial of the image from the year 1000 to the eve of the Reformation. In: Hoeps 2007

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 191

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 194

- ^ Lexicon of the Middle Ages, Art. "Image", Vol. 2, Col. 148

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 199

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 193

- ↑ Lexicon of the Middle Ages, Art. "Bildkatechese", Vol. 2, Col. 153–154

- ↑ Scribner 1990, p. 14

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 17f

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 198

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 197

- ↑ Wirth 2007, pp. 207ff

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 45

- ↑ Göttler, in: Scribner 1990, p. 266

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 203

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, pp. 43-47; Wirth 2000

- ↑ Jezler, in: Dupeux u. a. 2000

- ↑ cit. n. Scribner, in: ders. (Ed.) 1990, p. 11

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 32

- ↑ Wirth, in: Dupeux u. a. 2000

- ↑ Göttler, in: Scribner 1990, p. 293

- ↑ Göttler, in: Scribner 1990, p. 267

- ↑ Wirth 2007, pp. 210f.

- ↑ Göttler, in: Scribner 1990, pp. 280-281, 287-291

- ↑ Göttler, in: Scribner 1990, p. 265ff

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 209

- ↑ Wirth 2007, p. 210ff

- ↑ Quotation from Göttler, in: Scribner 1990, p. 293

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 31

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 8ff

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 15, after Warnke 1993

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 11

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, pp. 29, 148

- ↑ Tabular data: Schnitzler 1996, p. 146f.

- ^ Burkhard Kunkel: work and process. The visual arts equipment of the Stralsund churches in the late Middle Ages - a work history . Berlin 2008, p. 126-137 .

- ↑ Dupeux et al. a. 2000

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 148.

- ↑ Göttler in: Scribner 1990, p. 269

- ↑ cit. n. Schnitzler 1996, p. 148

- ↑ after Helmut Völkl : Orgeln in Württemberg. Hänssler-Verlag, Neuhausen-Stuttgart 1986, p. 15.

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 149

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 150

- ↑ Schnitzler 1996, p. 152

- ^ Christin, Olivier, France and the Netherlands - The second iconoclasm, in: Dupeux, Cécille; Jezler, Peter; Wirth, Jean (Ed.), Iconoclasm. Madness or God's will ?, Bern 2000, p. 57.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 57.

- ↑ Norbert Schnitzler: Iconoclasm - Iconoclasm. Theological picture controversy and iconoclastic action during the 15th and 16th centuries. Munich 1996, p. 155.

- ↑ An overview of the clergy active in the southern Netherlands during the uprisings of 1566 can be found in: Phyllis Mack Crew: Calvinist Preaching and Iconoclasm in the Netherlands 1544-1569. Cambridge 1978, pp. 182-196.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 6 ff.

- ↑ Public Calvinist worship services were held in Tournai, Valencienes and West Flanders as early as the first half of the 16th century, but were banned by the Catholic government in 1563. Ibid., P. 6.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 8.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 12.

- ↑ Ibid., P. 12. ff.

- ^ David Freedberg : Iconoclasm and Painting in the Revolt of the Netherlands 1566-1609. Oxford 1972, p. 14 ff.

- ↑ Olivier Christin: France and the Netherlands - The second iconoclasm. P. 58.

- ↑ Ludwig Binder: Johannes Honterus and the Reformation in the south of Transylvania with special consideration of the Swiss and Wittenberg influences . In: Zwingliana . 2010, ISSN 0254-4407 , p. 651-653 .

- ^ Karl Reinert: The foundation of the Protestant churches in Transylvania . In: Studia Transilvanica (5) . Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar 1979, p. 136 .

- ^ Heinrich Zeidner: Chronicles and Diaries, Sources for the History of the City of Kronstadt, Vol. 4 . Kronstadt 1903, p. 504-505 . , quoted from Emese Sarkadi: Produced for Transylvania - Local Workshops and Foreign Connections. Studies of Late Medieval Altarpieces in Transylvania. PhD dissertation in Medieval Studies . Central European University , Budapest 2008 ( ceu.hu [PDF; accessed October 29, 2017]).

- ↑ Evelin Wetter: The pre-Reformation legacy in the furnishings of Transylvanian-Saxon churches . In: Ulrich A. Wien and Krista Zach (eds.): Humanism in Hungary and Transylvania. Politics, Religion and Art in the 16th Century . Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna 2004, ISBN 978-3-412-10504-4 , pp. 28 .

- ^ Georg Daniel Teutsch: Document book of the Protestant regional church in Transylvania II. Sibiu, 1883, p. 105

- ^ Maria Crăciun: Iconoclasm and Theology in Reformation Transylvania: The Iconography of the Polyptych of the Church at Biertan . In: Archive for the history of the Reformation (95) . 2004, p. 93-96 .

- ↑ Vasile Drǎguţ: Picturile mural de la Medias. O importantâ recuperare pentru istoria artei transilvânene. In: Revista muzeelor şi monumentelor. Monumente istorice si de artâ 45 (1976), No. 2, pp. 11-22

- ↑ Dana Jenei: Picturi mural din jurul anului 1500 la Medias (Murals from around the year 1500 in Medias) . In: Ars Transilvaniae XXI . 2012, p. 49-62 .

- ^ Victor Roth: The frescoes in the choir of the church at Malmkrog. In: Correspondence sheet of the Association for Transylvanian Cultural Studies. Vol. 26, 1903, ZDB -ID 520410-0 , pp. 49-53, 91-96, 109-119, 125-131, 141-144.

- ↑ Hermann Stoeveken, Which Church is the Church of Christ? , Verlag Kreuzbühler, 1844, p. 101