Thomas Murner

Thomas Murner (born December 24, 1475 in Oberehnheim , † before August 23, 1537 ) was an Alsatian Franciscan , poet and satirist , humanist and important controversial theologian of the early Reformation period .

Life

Educational path

Thomas Murner was born in 1475 as the son of a respected citizen in Oberehnheim (today Obernai, Alsace ). Because of a birth defect, he always suffered from a slight limp; Polio is also being considered. In 1481 his family moved to the free imperial city of Strasbourg . The ailing Murner attended the monastery school in the Franciscan convent and entered the Upper German (Strasbourg) province of the Franciscan Order as early as 1490. Four years later, 19-year-old Murner was ordained a priest . In Strasbourg he will have become known with the sermons of Johann Geiler von Kaysersberg and the ship of fools by Sebastian Brant . Both authors were formative for his later works.

The superiors of the order recognized the talent of the young brother and made it possible for him to study at various universities in Europe. From 1494 Murner went on trips and studied at at least seven universities. He began his studies in Freiburg im Breisgau (1494–1498), completed a semester in Cologne (1498) and then a semester in Paris (1498/99). Then he turned to eastern Central Europe. The stations were the universities of Rostock (1499), Krakow (1499/1500), Prague (1500/01) and Vienna . After obtaining his master's degree in fine arts in Freiburg im Breisgau and the Baccalaureus theologiae in Krakow in 1498 , he returned to Strasbourg in 1501, where he began to work as a preacher and teacher at his mother monastery. After a short time there was a dispute with the city's leading humanists about the national identity of Alsace. The conflict degenerated into a personal feud between Murner and Jakob Wimpfeling .

Murner and Wimpfeling

Jakob Wimpfeling, the celebrated Alsatian humanist (1450–1528), like Murner, had resettled in Strasbourg in 1501. At the end of 1501, presumably in response to a lecture by Murner, he had written Germania , in which he asserted that Strasbourg and the whole of Alsace had never been Gallic , and that Charlemagne and his father Pippin were also Germans the origin of Alsace is entirely Germanic . This is also reflected in the many German place names. A second concern of Scripture was the demand for a secular humanistic school in Strasbourg. The writing earned Wimpfeling a lot of praise, but challenged the French faction. In addition, the Franciscans saw their school activities threatened by Wimpfeling's project. Murner, who had started to teach publicly in the city in 1501, made himself the spokesman for Wimpfeling's opponents. In the summer of 1502 he published Germania Nova, a counter-writ, in which he uncovered Wimpfeling's weak historical evidence and, where he failed to do so, tried to make it look ridiculous.

Wimpfeling reacted extremely irritably to Murner's answer and managed to get the Strasbourg council to stop the distribution of this publication. He also sent a circular to his friends and students asking them to defend him against the outrageous attacks by the young and unknown Murner. Soon a text in defense of Wimpfeling was published by his admirer Thomas Wolf (1475–1509) ( Defensio Germaniae Jacobi Wympfelingii , Freiburg i. B. 1502). On the title page, Thomas Murner is shown on one side. He can be recognized by the banner preter me nemo ( nobody but me ), which should express his arrogance. On the other side are Wimpfeling and his students. The Defensio was not so much a defense of Wimpfeling as an actual settlement with Murner. In a second work, also edited by Thomas Wolf ( Versiculi Theodorici Gresemundi , Strasbourg 1502), Murner was covered with a series of rough swear words. A dirty name Mur-nar (foolish cat) should accompany him for life. Murner's answer to the insults was an eulogy ( Honestorum poematum condigna laudatio , Strasbourg 1503) in which he called on his opponents to a public argument. The writing was probably banned immediately after its publication and thus forms the provisional end of the dispute.

Spiritual and academic career

Thomas Murner traveled a lot as a result. He was entrusted with various tasks by his order. He took part as a preacher in several chapters of the order and was active as a lecturer ( reading master ) in various monasteries , including the Franciscan monasteries of Freiburg im Breisgau (1508), Bern (1509), in the Barefoot Monastery in Frankfurt am Main (1511-13) ) and in Strasbourg (1520). He held the senior post of Guardian in von Speyer (1510) and Strasbourg (1513-14).

In addition to his duties in the order, Murner also advanced his academic career. He completed his theology studies in Freiburg in Breisgau in 1506 with a licentiate and a doctorate . From 1506 to 1507 he taught logic at the University of Cracow . Murner also stayed in Italy on various occasions for further study visits. Already at a ripe old age, he decided in 1518 to undertake a second degree at the law faculty of the University of Basel . A year later, against the opposition of the Freiburg legal scholar Zasius , he acquired the Doctor juris utriusque (Doctor of both rights, civil and canon law).

The numerous changes of location were often accompanied by disputes. In Cracow, where he used the didactic card games ( Chardiludium logicae ) he had invented for his students in 1507 , he was accused of heresy by the university , but was able to prevent charges with his explanations. As early as 1502, Jakob Wimpfeling and his students had made fun of Murner's mnemonic card games, and Zasius and Erasmus had also commented critically on it.

In Freiburg Murner again got into a dispute between humanists. In the dispute between Jakob Locher and Wimpfeling, he sided with Locher. He negotiated the hostility of Zasius, who, as a religious, denied Murner's competence in poetry. Following derailments in his preaching activity, he was probably transferred to Bern by his superiors in 1509 at the request of the university.

During his stay in Bern, he experienced the final phase of the famous Jetzer trial , which ended in 1509 with the execution of four Dominicans , as a reading master in the Barfüsserkloster . Murner published several pamphlets against the Dominicans: De quattuor heresiarchis , in German burned by the heretical preaching order of the observantz in Bern in Switzerland . Murner's writings received a lot of attention and received several editions. In this writing, Murner used German rhyming pairs for the first time, a literary form that he later used with pleasure.

Poeta laureatus

The first highlight was a writer for Murner the year 1505, when he was in Vienna from the Roman-German king and later Emperor Maximilian I to the Poet Laureate was crowned. This award was associated with high esteem and authorized Murner to wear his own coat of arms. Murner's first publications were made in 1498/99. In 1498 he published a Practica , a calendar with an annual horoscope, and in 1499 the Invecta contra astrologus , a publication in which he questioned the usefulness of astrologers in connection with the Swabian War. Also in 1499, the Tractatus pertulis de phitonico contractu , in which he linked his early childhood paralysis with witchcraft magic, was printed.

The total of more than 70 works by Murner that have been preserved indicate his complex and extensive interests. In addition to theological treatises, he wrote, among other things, writings on astrological, historical, didactic and legal topics. There are numerous pamphlets that he wrote in response to his opponents. In addition, Murner also worked as a translator of foreign works. He translated writings by Luther , Erasmus and Hutten from Latin into German. On behalf of his order he also translated some texts from Hebrew into Latin and German ( Der iuden benedicite as sy gott den heren praise, and in the umb die speyß dancken ). His most important translation works include: a first German translation of Virgil's Aeneis ( Vergilii Maronis dreyzehen Bücher von dem Tewren hero Enea , 1515), a vernacular translation of the Institutiones des Justinian ( Institutes ein warer vrsprung vnnd sundament des Keyserlichen Rechtsens , 1519) and the Translation of the world history by Sabellicus ( Hystory von der anbeschaffener welt ), his late work, which was no longer printed. This work, which he presumably provided with numerous illustrations by hand, has been partially preserved as a manuscript. Although more than two thirds of his writings were written in Latin, it is above all his German satires that have determined the Murner image most effectively to this day and earned him the reputation of one of the most important satirists of the 16th century.

Murner as a satirist

Murner received a lot of attention through his German-language satires. Initially, he was based heavily on the fool's literature of his models Sebastian Brant and Geiler von Kaysersberg. He proved to be a master of this genre and received great acclaim. In 1512 Murner published two satires written in German verse: the jester complaint and the Schelmenzunfft . In the conjuration of fools , Murner referred directly to Brant's ship of fools and sometimes also used its illustrations. Like Brant, he makes the fools represent a whole range of human follies. With a kind of exorcism these fools are driven out of their follies. In both works he reveals grievances in medicine and other sciences.

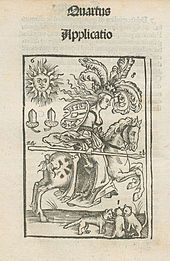

He reaps even more success with the picaresque guild . In this verse satire the poet, as a guild writer, lists all the vices of his rascals. Each chapter is headed with a proverbial phrase and illustrated with a woodcut. The guild members come from all walks of life, from lazy students to quarrelsome councilors. In his bitter criticism, Murner does not omit the incompetent clergy, about which he is preached in the first chapter under the proverb of blue ducks .

In 1515 the garbage from Schwindelszheym appeared . The main characters in this poem are the miller, who invited a rogue society to a jarzit , his boisterous wife Gredt Müllerin and a donkey. In addition to criticizing the love addiction, embodied in Gretmüllerin, Murner, in turn, takes a sharp target on the clergy. So he lets the donkey appear in the form of a canon, a guardian, a prior and a doctor of a university.

The Schwindelsheim mill is considered to be the “replacement script ” of Geuchmat , which Murner had written in 1514/15 and which initially fell victim to (intra-Franciscan) censorship in Strasbourg. It was not until 1519 that Murner succeeded in printing this “misogynist pamphlet” at Adam Petri in Basel. The Geuchmatt is a meadow of lustful people. Murner himself appears in this satire: with the gauch (cuckoo as a symbol of the fool) on his shoulder, he reads out the 22 Geuch articles as Cantzler der geuchmatten. Under the rule of Mrs. Venus , the loveliest women use all the tricks to seduce the wybischen mannen . Even contemporaries had criticized Murner for having met with great approval not only because of its moralizing intentions, but also because of its lascivious content.

In the pre-Reformation period Murner had not only written satires, but also dealt with more serious subjects. In the book Ein andechtig Geistliche Badenfahrt , published in 1514, Murner showed himself from his pastoral side. Well stimulated by his own health-related spa treatments, he describes a symbolic spa treatment in which Jesus Christ is depicted as the lifeguard, Murner as the patient and the bath as an allegory for penance.

Murner and the Reformation

In his writings before 1520, Murner had denounced the church's grievances in sometimes harsh words and called for a thoroughgoing reform. He had never questioned the institutions of the church. When he returned to Strasbourg in 1520 and saw how some of the preachers and large circles of the Strasbourg population responded to Luther's writings, he recognized the danger of a split in the church and began to oppose it in a journalistic way. In autumn 1520 he wrote a Christian and fraternal admonition to Martin Luther. The writing, published anonymously and in a conciliatory tone, was directed against Luther's attack on Holy Mass in the sermon of the New Testament . By the end of 1520 Murner had three more anonymous writings printed against Luther, the tone of which became more polemical from time to time. In December he also published a German translation of Luther's De captivitate Babylonica ecclesiae , also without giving a name, with the intention of warning the public about the new teaching. Luther, who was informed about the authorship of the scriptures by the Strasbourg preacher Wolfgang Capito , only turned against Murner in 1521 and accused him of not arguing according to the scriptures. Murner had since stepped out of anonymity and posted a leaflet in various places in the city of Strasbourg in which he defended himself against the many pamphlets directed against him and justified his stance against Luther. Although Murner brought about a ban on the writings directed against him by the council, he could not prevent their distribution, especially the two popular Reformation dialogues Karsthan and Murnarus Leviathan .

Like his opponents, Murner remained active. To a glorification of Lutheran teaching in song form by Michael Stifel , he also responded with a song entitled Ain new song of the undergang of the Christian faith and thus reaped a flood of hostile pamphlets. Murner reflected on his satirical qualities and responded with his 4800 verse poem From the great Lutheran fool , which was illustrated with numerous woodcuts. The writing, which is regarded as the climax in Murner's anti-reformist polemics, is widely recognized in Reformation research to this day and is referred to as his masterpiece. In the script, Murner himself appears in the figure of the cat-headed grumbler, whom his opponents like to accuse him of, and tries to conjure up the Lutheran fool , embodied in a swollen monster. Despite the literary brutality expressed in the scriptures, this satire is considered to be "the most ingenious indictment against the Reformation par excellence". The pamphlet, which appeared in December 1522 by the last old-believing printer, Hans Grüninger , was confiscated shortly after its publication; a second edition didn't do much better. In 1522 Murner had translated a work by Henry VIII on the sacraments into German and in 1523 went to England for a few weeks at an alleged invitation of the king. After his return to Strasbourg, he took part in the Reichstag in Nuremberg in 1524 as the envoy of the Strasbourg bishop . Murner could not prevent the introduction of the Reformation in Strasbourg (April 19, 1524). He and his supporters have now been forbidden by the council to print further pamphlets. Murner then set up a private printing press in the Franciscan monastery. However, the mood in the population became increasingly hostile. In September 1524 there was a real crowd against the old-believing preachers. The mob looted Murner's apartment and destroyed his printing works. Unlike the Augustinian preacher Konrad Treger , Murner could not be arrested. He had already brought himself to safety in his hometown Oberehnheim. Murner tried in vain to seek compensation from the Strasbourg Council for the destruction. On the contrary, he was not allowed to return to the city.

Murner in the Swiss religious struggle

Murner only found refuge in Oberehnheim for a short time. When the town was besieged in the German Peasants' War in 1525 , the peasants demanded the extradition of the clergy who had fled. Therefore Murner fled the city in May 1525 and went to Lucerne . Destitute and ill, he was admitted to Lucerne and entrusted with the office of reading master and preacher in the Barfüsserkloster and later the city pastor. Soon after his arrival he took up the fight against the Reformation again and set up a printing shop in his monastery. During his time in Lucerne (1525–1529) a total of 21 pamphlets, mostly anti-reformist pamphlets, left his printing house. In addition to Zwingli, his main journalistic opponents were Utz Eckstein from Zurich and Niklaus Manuel from Bern. One of the first writings published in Lucerne was directed against his friar and predecessor as Lucerne master reading Sebastian Hofmeister and against the Ilanz Religious Discussion .

As a countermeasure against the Zurich Reformation, the five traditionally faithful places in central Switzerland organized the Baden disputation . At these religious talks, which took place in the Baden parish church from May 19 to June 8, 1526, Murner was one of the main theological representatives of the old faith alongside Johannes Eck and Johann Fabri . Murner did not excel through theological arguments but rather through tough attacks against Ulrich Zwingli . He accused him of not appearing and read a forty-fold "disrespect" against him in the closing session. After the disputation was over, Murner was commissioned to print the disputation files in his printing house. Although he was accused of forgery of the files by the opposing side, this could never be proven. Murner caused quite a stir in the Swiss Confederation in 1527 when he published the Lutheran Evangelical Church Thief and Heretic Calendar. On this pamphlet, disguised as a wall calendar, he vilified most of the Swiss reformers in the sharpest way. Zwingli, whom he depicted hanging on the gallows, was accused of being a liar and a thief.

Murner refuses to take part in the Bern disputation , which was convened by the Reformation side in 1528 , because he denied legitimacy to these talks. However, he came up against the attitude of the Bern reformers with several sharp writings. So he defended the mass with the writing Die gots heylige mess . In connection with the Bern Reformation, the two satirical writings on the bear testament and the bear toothache were created . As a result, Murner was sued by Bern and Zurich at the end of 1528 for his pamphlets. However, the process was canceled for strategic reasons. In the peace negotiations for the first Kappeler Landfrieden (1529), the Reformed towns insisted on an extradition of Murner to bring him to court. Murner was warned in good time and evaded arrest by fleeing Lucerne.

Back in Oberehnheim

Murner probably fled Lucerne back to Alsace via Valais . For now, he went to Heidelberg, where he temporarily the elector V. Ludwig was welcomed. Later (1532) he returned to Oberehnheim, where he worked as a pastor at St. John's Church. Bern and Zurich also made representations to Strasbourg and demanded that Murner be imprisoned and deprived of his pension as the alleged main cause of the First Kappel War . But even here they did not get through with their demands.

In the anti-reformatory journalism of Murner nothing more has recently been heard in Oberehnheim. In addition to his work as a pastor, he worked on a translation of the world history of Sabellicus from Latin and provided them with drafts for later woodcuts. However, this historical work was no longer printed. At least three manuscript volumes with a total of 344 illustrations have survived.

From Lucerne he received several offers for the schoolmaster's position. Murner finally refused this offer in 1535. Two years later he died in his hometown at the age of almost 62.

Murner's effect

Thomas Murner combines positions of humanism and the old Roman Catholic faith; this results in some insurmountable inner tensions on the part of the author, which are also reflected in his works.

Works

Detailed catalog raisonné at: Friedrich Eckel: Thomas Murner's foreign vocabulary. A contribution to the history of words in the early 16th century; with a complete Murner bibliography. Göppingen 1978.

Pre-Reformation writings

- Invectiva contra Astrologos , Strasbourg 1499 (digital copy)

- Germania Nova , Strasbourg 1502.

- Chartiludium logicae , Cracow 1507.

- Logica memorativa , Strasbourg 1509 (digitized version )

-

De quattuor heresiarchis , Strasbourg 1509 (digitized version )

- Of the four heretic ones , Strasbourg 1509 (digitized version )

- Ludus studentum Friburgensium , Frankfurt am Main 1511 (digitized version )

- Arma patientie contra omnes seculi adversitates , Frankfurt am Main 1511 (digitized version)

-

Benedicite iudeorum , Frankfurt am Main 1512 (digitized version )

- The iuden Benedicite , Frankfurt am Main 1512 (digitized version)

- Fool's turn , Strasbourg 1512.

- Schelmenzunfft , Frankfurt am Main 1512 Digitized Augsburg 1514

- A real ecclesiastical Badenfart , Strasbourg 1514.

- The waste from Schwyndelszheym vnd Gredt Müllerin Jarzit , Strasbourg 1515.

- The geuchmat , Basel 1519 digitized

Writings against Luther

- A Christian admonition , Strasbourg 1520 (digitized version )

- Learn and preach by Doctor Martinus luters , Strasbourg 1520.

- Von dem babstenthum , Strasbourg 1520 (digitized version )

- To the most powerful and most transparent aristocratic Tütscher nation , Strasbourg 1520 (digitized version )

- How doctor M. Luter usz moved wrong causes spiritually right burned , Strasbourg 1521.

- Ain new song about the change of the Christian faith , Strasbourg 1522 (digitized version )

- Whether the Künig usz engelland is a liar or the Luther , Strasbourg 1522 (digitized version )

- Digitized by the great Lutheran Fool , Strasbourg 1522

Writings from Lucerne

- Murneri responsio libello cuidam , 1526.

- Responsible for a worhaffigs , 1527 (digitized version )

- The Lutheran Protestant Church Thief and Heretic Calendar , 1527.

-

The disputation in front of the xij places of a laudable eidtgnoschetzt , 1527 (digitized version )

- Causa Helvetica orthodoxae fidei , 1528 (digitized version)

- Here would be indicated as before Christian sacrilege , 1528.

- The gots heylige mess stifled by god alone , 1528 (digitized version )

- Old Christian Berries Testament , 1528.

- From the young berries zenvve im mundt , 1529.

Legal writings

- Utriusque iuris tituli et regule , Basel 1518 (digitized version )

- Institutes a war origin and the foundation of the priestly law , Basel 1519 (digitized version )

- The keiserlichen stat right an entrance and wares foundation , Strasbourg 1521 digitized

Translations

- Vergilij maronis dryzehen Aeneadic books , Strasbourg 1515 (digitized)

- Ulrichen von hutten ... from the wonderful artzney des holtz Guaiacum called , Strasbourg 1519.

- From the Babylonian Gefengknuß of the Churches by Doctor Martin Luther , Strasbourg 1520 (digitized version )

- Confession of the sacraments vider Martinum Lutherum , Strasbourg 1522 (translation of the Assertio Septem Sacramentorum of Henry VIII. )

- Marcii Antonii Sabellici History of anbeschaffener Welt , 1534/1535 (3 of 10 volumes preserved as manuscripts)

Revisions

-

Franz Schultz (Ed.): Thomas Murner. German fonts with the woodcuts of the first prints. (9 vol.) Berlin Leipzig 1918–1931.

- From the heretic ed. by Eduard Fuchs

- Badenfahrt ed. by Victor Michels

- Fool's Summoning ed. by Meier Spanier

- The rogue guild ed. by Meier Spanier

- The mill of Schwindelsheim and Gredt Müllerin Jahrzeit ed. by Gustav Bebermeyer

- The Geuchmat ed. by Eduar Fuchs

- Small writings: prose writings against the Reformation. 3 vol. Ed. by Wolfgang Pfeiffer-Belli

- From the great Lutheran fool, ed. by Paul Merker

- Wolfgang Pfeiffer-Belli (ed.): Thomas Murner in the Swiss battle of faith. Münster in Westphalia 1939.

- Hedwig Heger (Ed.): Marcii Antonii Sabellici Hystory from anbeschaffener Welt. Translation of the Enneades by Mark Antony Sabellicus. (4 vol.) Karlsruhe 1987, ISBN 3-7617-0251-5 .

- Adolf Laube (ed.): Pamphlets against the Reformation (1518-1524). Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-05-002815-7 .

- Adolf Laube (ed.): Pamphlets against the Reformation (1525-1530). Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-05-003312-6 .

- Karsthans. Thomas Murner's “Hans Karst” and its impact in six texts from the Reformation period: “Karsthans” (1521); 'Gesreu biechlin neüw Karsthans' (1521); 'Divine Mill' (1521); 'Karsthans, Kegelhans' (1521); Thomas Murner: 'From the great Lutheran fool' (1522, excerpt); 'Novella' (ca.1523). Edited, translated and commented by Thomas Neukirchen. (= Supplement to the Euphorion. 68). Heidelberg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8253-5976-8 .

- From the great Lutheran fool (1522). Edited, translated and commented by Thomas Neukirchen. (= Supplements to Euphorion. 83). Heidelberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-8253-6388-8 .

literature

- Thomas Murner: Alsatian theologian and humanist 1475–1537. Exhibition of the Badische Landesbibliothek Karlsruhe. Karlsruhe 1987, ISBN 3-88705-020-7 .

- Hedwig Heger: Thomas Murner. In: Stephan Füssel (ed.): German poets of the early modern period (1450–1600). Your life and work. Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-503-03040-9 , pp. 296-310.

- Erwin Iserloh : Thomas Murner (1475–1537). In: Erwin Iserloh (ed.): Catholic theologians of the Reformation period (= Catholic life and church reform in the age of religious schism. 46). Volume 3, Münster 1987, ISBN 3-402-03345-3 , pp. 19-32.

- Friedrich Lauchert : Studies on Thomas Murner. In: Alemannia 18, 1890, pp. 139-172, pp. 283-288, and Alemannia 19, 1892, pp. 1-18.

- Theodor von Liebenau: The Franciscan Dr. Thomas Murner. Freiburg im Breisgau 1913. (digitized)

- Heribert Smolinsky : Thomas Murner and the Catholic Reform. In: Heribert Smolinsky (Ed.): In the light of church reform and reformation. Münster 2005, ISBN 3-402-03816-1 , pp. 238-250. (PDF)

- Waldemar Kawerau: Thomas Murner and the German Reformation. Halle 1891. Full text in Google Book Search USA

- [Catalog] Thomas Murner. Alsatian theologian and humanist (1475–1537) , [an exhibition by the Badische Landesbibliothek Karlsruhe and the Bibliothèque Nationale et Universitaire de Strasbourg], ed. from the Badische Landesbibliothek Karlsruhe, Karlsruhe: Badische Landesbibliothek, 1987, 239 pp.

- Lexicon entries

- Franz Josef Worstbrock (Ed.) :: German Humanism 1480–1520. Author Lexicon. Volume 2, de Gruyter, Berlin 2009-2013, Col. 299ff.

- Peter Ukena: Murner, Thomas. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-428-00199-0 , pp. 616-618 ( digitized version ).

- Marc Lienhard : Murner, Thomas . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 23, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1994, ISBN 3-11-013852-2 , pp. 436-438.

- Heribert Smolinsky : Murner, Thomas. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 6, Bautz, Herzberg 1993, ISBN 3-88309-044-1 , Sp. 366-369.

- E. Martin: Murner, Thomas . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1886, pp. 67-76.

- Rainald Fischer: Murner, Thomas. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland .

- Brockhaus' Conversations Lexicon. 11th edition. Volume 10, Leipzig 1867, pp. 503-504.

Web links

- Literature by and about Thomas Murner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Books by and about Murner at the Berlin State Library

- Card games by Thomas Murner

- Works by Thomas Murner at Zeno.org .

- Evidence of works on the web (Mi-My)

- Short biography on Heidelberg hypertext server

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f Philippe Dollinger: The life of Thomas Murners. In: Thomas Murner. Alsatian theologian and humanist. Karlsruhe 1987, pp. 21-34.

- ↑ German Humanism 1480–1520. 2009, col. 300.

- ↑ a b c d e Hedwig Heger Thomas Murner (1993)

- ↑ For the discussion cf. Emil von Borries : Wimpfeling and Murner in the struggle for the older history of Alsace: a contribution to the characteristics of early German humanism. Heidelberg 1926 (digitized version)

- ↑ a b c d e f Liebenau: The Franciscan Dr. Thomas Murner (1913)

- ↑ Cf. Eduard Fuchs: Introduction. In: Thomas Murner: From the heretic ones. Berlin 1926.

- ↑ Cf. Dirk Jarosch: Thomas Murner's satirical writing. Studies from a thematic, formal and stylistic perspective. Hamburg 2006, ISBN 3-8300-2436-3 .

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki : Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. Ernst Giebeler, Darmstadt 1982, ISBN 3-921956-24-2 , pp. 153 and 155.

- ^ Dollinger: Das Leben Thomas Murners (1987), p. 29.

- ↑ a b Iserloh: Thomas Murner (1987)

- ↑ a b cf. Marc Lienhard: Thomas Murner and the Reformation. In: Thomas Murner. Alsatian theologian and humanist (1475–1537). Karlsruhe 1987, pp. 63-77.

- ↑ Cf. Tilman Falk: The illustrations for Murner's Sabellicus translation. In: Thomas Murner. Alsatian theologian and humanist. Karlsruhe 1987, pp. 113-128.

- ↑ Heribert Smolinsky: A personality at the turn of the ages: Thomas Murner between the late Middle Ages and the modern age: Lecture on the occasion of the opening of the exhibition “Thomas Murner. Theologe und Humanist 1475–1537 ”on November 27, 1987. Badische Bibliotheksgesellschaft, 1988, ISBN 3-89065-015-5 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Murner, Thomas |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Catholic publicist and poet |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 24, 1475 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Oberehnheim |

| DATE OF DEATH | before August 23, 1537 |

| Place of death | Oberehnheim |