Evangelical Church AB in Romania

The Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Romania , mostly abbreviated as Evangelical Church AB in Romania , is an Evangelical Lutheran denominational and linguistic minority church with now only about 11,448 members (as of 2019), mainly the German-speaking Evangelicals in Transylvania (see Transylvania Saxony ) and in the capital Bucharest. The bishopric is Sibiu . Reinhart Guib has been Bishop of the Evangelical Church AB in Romania since November 27, 2010 . The language of preaching is German . The name of the church refers to the Augsburg Confession of 1530, one of the basic confessional writings of the Evangelical Lutheran churches .

history

Beginnings

The Reformation in Transylvania began as a city reformation. The German Reformation movement was already known in Transylvania in the early 1520s. The humanists and reformers Johannes Honterus and Valentin Wagner initially represented a middle position between the extreme positions of the Catholic Church and the Reformation movement. Their reforms were aimed at philology, ethics and pedagogy. In 1542 the liturgical reform was carried out in Kronstadt, in 1543 the Reformation booklet for Kronstadt and Burzenland by Honterus was published. In 1550, the University of Nations decided that the entire right-wing nation on the royal floor should turn to Lutheran doctrine. The first church in which the new faith was preached was the Black Church in Kronstadt . 1553, Paul Wiener, the first evangelical bishop was installed. In 1572 the church introduced the Lutheran confessions and moved the bishopric from Sibiu to Biertan (until 1868). In 1563 a synod in Mediaş had stipulated that candidates for a municipal office should be "of sufficient education" (mediocriter eruditi) ; the criteria for this were only vaguely defined. The duration and content of the course were not specified. Often the students returned to Transylvania after a short stay at a - mostly German Protestant - university and worked there as teachers before taking on church offices. For centuries, the Protestant Church AB remained the national church and also the guardian of the German-speaking school system of the Transylvanian Saxons - a role that it has increasingly performed again in recent times.

19th century

The traditionally close contacts to German universities were maintained until the early 19th century. Lutheran theologians from Transylvania often studied in Germany. In the course of the Karlsbad resolutions of 1819, the Austrian government prohibited studying at German universities; the ban lasted until 1830. Unrestricted access for Austrian students to German universities was only possible again from 1848. In order to continue to ensure theological training, a Protestant theological training institute was founded in Vienna in 1821 under the direction of Johann Wächter , at which Lutheran scholars from Transylvania were also trained in the future. The inadequate education of the Lutheran clergy led to reform efforts that could not initially be implemented in the university-theological field and therefore concentrated on reforming the grammar school system. From 1837 onwards, a degree in theology was a prerequisite for being elected parish priest.

In 1876 the church practically became the estate administrator of the dissolved nation university . She owned extensive estates, forests - the so-called church grounds - and hundreds of properties in the form of churches, rectories, school buildings, townhouses (including the Brukenthal Palace in Sibiu), the Brukenthal Collection , etc.This property became (with the exception of the church buildings ) 1946, partly already in the 1930s, expropriated by the Romanian state. In 1921 the Hungarian congregations separated and constituted themselves as an independent church, with which two Lutheran churches have existed in Transylvania and Romania since then. The Hungarian-influenced church is now called the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Romania .

1930-1944

At the time of National Socialism in Germany, the National Socialist “renewal movement” in Romania from around 1930 gained increasing support from poorer peasants and from 1935 political influence. The "German People's Community in Romania" (DVR) under Fritz Fabritius , with its Nazi-inspired "People's Program", was in conflict with the more radical National Socialist "German People's Party of Romania" (DVR) by Alfred Bonfert and Waldemar Gust . Böhm (2008) shows how both organizations concentrated in the interwar period on “not splitting the attention of Romanian Germans” by orienting their polemics to “friend-foe relationships”. In addition to Hans Otto Roth , Rudolf Brandsch and the Banat Swabian Kaspar Muth , these enemies also included the Evangelical Bishop Viktor Glondys , who were exposed to stereotypical, undifferentiated hate speech. Bishop Glondys had already spoken out in a sermon in 1931 against a racially alienated "ethnic theology". At the same time it was important to him to settle the disputes among the believers.

On January 14, 1936, the VDR concluded a "truce" with the church leadership on Fabritius' orders. However, the DVR did not recognize this and continued to fight bitterly against Glondys, the state consistory and the “Volksgemeinschaft” (VDR). Protestant pastors such as Friedrich Benesch , who openly supported the National Socialist ideology, were removed from office. In order to avoid intra-church party-political conflicts, the state consistory issued circular Z924 / 37 on February 14, 1936, in which “church and school employees and all candidates and students of theology and the teaching post” were instructed to “belong to all to dissolve political parties and groups and to resign immediately from the party-political front. "Those who refused to obey should be removed from office. The dismissed pastors met in so-called “people's evenings” as early as August 1935 and drafted their own 15-point program. With reference to Articles 7 and 28 of the Augsburg Confession, they claimed that the circular from 1936 was “un-Evangelical in the sense of the Reformation Confession.” According to Böhm (2008), this group played a “fateful and anti-church role” in Romania until 1944.

In August 1940, Bishop Glondys suffered a severe stroke and received medical treatment abroad until November 30th. On September 27, 1940, the radical National Socialist Andreas Schmidt was appointed "ethnic group leader" of the Germans in Romania by the SS headquarters in Berlin. On November 9, 1940, the " NSDAP of the German Ethnic Group in Romania (DViR)" was founded, whose claim to sole representation extended to the Evangelical Church. In February 1941, Glondys was forcibly retired. From 1941 his successor Wilhelm Staedel operated the consistent " conformity " of the church office. He found resistance in the "defense ring" led by Episcopal Vicar D. Friedrich Müller.

Communist rule and Ceaușescu dictatorship

After the end of the Second World War, around 240,000 Transylvanian Saxons lived in Romania, a minority of around 1% of the country's population. The communist rule that established itself after 1948 did not need to give political consideration to this part of the population, which was also largely isolated internationally - in contrast to the Roman Catholic and Romanian Orthodox Churches. The communist religious policy controlled by Moscow brought a period of severe persecution, but also attempts by the church leadership to adapt to the demands of the communist rulers. Defamed as "collaborators of Hitler", between January 1945 and December 1949 between 70,000 and 80,000 Romanian Germans were deported to the Soviet Union, and again in June 1951 around 40,000 people were deported to the Bărăgan steppe . Memorial plaques in numerous Transylvanian churches remind of the losses from this time.

While the Romanian Orthodox Church was able to come to terms with the communist state and enjoyed limited privileges in return for its support of the regime, the religious life of the Evangelical Church AB was largely confined to the church walls and was subject to state expropriations as well as surveillance and harassment Securitate . During this time the church played an important role in maintaining the cultural identity of the Transylvanian Saxons. The bishops Friedrich Müller-Langenthal (1945–1969) and Albert Klein (1969–1990) succeeded in re-establishing the Evangelical Church through internal reforms and in leading it - not without compromising with the communist rulers. The reappearance of the " Kirchliche Blätter ", the oldest and most important publication, from 1973 onwards, was of inner importance. The Transylvanian ensured close personal cooperation with the Evangelical Churches of the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR as well as the World Council of Churches and the Lutheran World Federation Church ideal and material support from outside. In particular, the activities of the Diakonisches Werk, which are dedicated to all needy, as well as Klein's efforts for ecumenical cooperation with other denominations strengthened the position of the Evangelical Church AB in Romania.

1970s until today

Since the massive emigration of most of its members to Germany since the 1970s, massive from 1990, the Evangelical Church AB has developed into a diaspora church. The radical loss of community members is closely linked to the historical and political events after the Second World War. There was a significant break between 1989 and 1996: Until 1989 the church had around 100,000 parishioners and in 1996 there were only around 19,000. With the collapse of the communist dictatorship and the resulting freedom to travel, a real “mass exodus” of the Transylvanian Saxons towards Germany began. Even before 1990, controlled emigration, mainly as a family reunification , had come about in a secret agreement by representatives of the government of the Federal Republic and the Securitate , which only after 1990 turned out to be a kind of " ransom for Romanian Germans ". The church leadership was helpless in the face of such developments and could only take note of the dramatic course. Because of the lack of prospects, most of the pastors and educators also emigrated. This gap was filled with self-sacrificing work by the pastors and lay people who stayed behind. During this difficult transitional period, Christoph Klein was elected bishop in 1990.

Bishop Christoph Klein retired in 2010. Reinhart Guib was elected as his successor as Bishop of Saxony on November 27, 2010. He was appointed to his office as the 36th Bishop of the Evangelical Church AB on the 3rd Sunday in Advent 2010.

With its social services such as the Evangelical Diaconal Association, its presence in German-speaking schools and a variety of cultural activities, for example the Media Organ Summer and the concerts in the Black Church in Kronstadt , the Evangelical Church AB in Romania has a much stronger public presence than its small number of members would be expected.

With Klaus Johannis , the former mayor of Sibiu, a member of the Evangelical Church AB was elected President of Romania in 2014.

structure

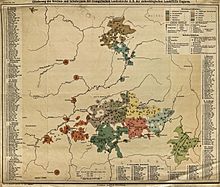

The church is administratively divided into several districts with independent (city) parishes and the many dependent small and micro parishes, the so-called diaspora. In total, community members are cared for in 250 localities.

In detail, the districts are based on historical circumstances, but have already been modified several times to take account of the decline in membership:

- Sibiu

- Schäßburg ; these include the Reener Ländchen , the Nösnerland and the diaspora communities in Bukowina

- Kronstadt ; this includes Bucharest

- Medias

- Mühlbach

Institutions

Although the Evangelical Church AB in Romania is very small in terms of members, it still has a number of its own institutions that enable it to train its own pastors and to actively participate in interreligious dialogue and to be a valued contact person, also internationally .

This also includes independent church-related institutions:

- Evangelical Academy of Transylvania

- Evangelical Theological Faculty of the University of Sibiu

- Institute for Ecumenical Research Sibiu

Direct church institutions are:

- Church papers , monthly journal of the regional church

- Friedrich Teutsch meeting and cultural center (also Friedrich-Teutsch-Haus ) in Sibiu (contains the regional church museum of the Evangelical Church AB and the central archive)

- Control center fortified churches (supervises restoration projects at churches (castles))

- Hermannstädter Bachchor and Jugendbachchor Kronstadt

- Archives of the Honterus parish in Kronstadt

In any case, the importance and attention given to the Evangelical Church AB does not correspond to the very small number of members, which is looked after by only 40 pastors in several urban and diaspora parishes.

financing

The church is funded from a variety of sources. On the one hand, voluntary church contributions are collected from the members; on the other hand, income is generated through donations, foundation services, grants from other regional churches in Germany, to a small extent state grants, and the rental of restituted buildings and apartments. In addition, many churches and to be World Heritage counting fortified churches used now touristy and thus represent another small source of income However, the properties of the church, which is now again a part of their old buildings, forests and land (often only after decades of litigation) are. was reimbursed, often barely borne by the now very small communities. Running costs are often not matched by corresponding income. Investments would also have to be made in the buildings first, as the latter are often completely neglected for decades in state ownership. New sources of finance must constantly be found in order to not only preserve the property that has been restored, but also the more than 250 church buildings and around 150 fortified churches and to cultivate the church forests, which poses great challenges for the Evangelical Church AB in Romania.

On the other hand, there is an extreme gap in financial resources between the urban and diaspora communities. The municipalities of Sibiu and Kronstadt, for example, are in possession of a large number of real estate worth millions through restitution and are considered to be rich due to their rental income. These congregations can afford an extended congregational life and also do charitable work. The churches there are also tourist magnets (the Black Church is visited by more than 2,000 people every day in the summer months) and can count on state / EU help in maintaining it, whereas the small diaspora communities with often only a handful of members are no longer an independent church and rectory can order.

Reformation commemoration 2017

On the 500th anniversary of the Reformation in 2017, the Evangelical Church AB is pursuing the project “Twelve apple trees for a clear word”. The aim is to “get your own members excited about the topicality of Reformation ideas.” The church convention planned for autumn 2017 in Kronstadt will serve this purpose under the motto: “For good reason: Evangelical in Romania”. In addition, the Evangelical Church in Romania would like to point out the European dimension of the Transylvanian Reformation as the basis of its present day self-image. This dimension is addressed through joint events with different accents, partners and churches, which are achieved through the symbolic planting of apple trees in twelve locations important for the Reformation in Transylvania ( Ljubljana (Slovenia), Turda (Romania), Kraków (Poland), Wittenberg (Germany) ), Medias (Romania), Krupina (Slovakia), Klausenburg (Romania), Kronstadt (Romania), Vienna (Austria), Augsburg (Germany), Basel (Switzerland), Hermannstadt (Romania)) find a thematic framework. The "apple tree" stands (according to a quote attributed to Luther ) for confidence, the "clear word" for the "Reformation way of speaking clear, evangelical words".

The anniversary of the Reformation should be "remembered, but not celebrated in a backward-looking manner". It is dedicated to “today's explosive topics such as 'Europe', 'tolerance', 'media' or 'education'”. Ultimately, the Romanian public should be reached through ecumenical events, more than 85% of whom belong to the Romanian Orthodox Church and to whom the Evangelical Diaspora Church is largely unknown.

literature

- Wilhelm Andreas Baumgärtner: In the clutches of the great powers. Transylvania between the Civil War and the Reformation. Schiller Verlag, Hermannstadt / Bonn 2010, ISBN 978-3-941271-44-9 .

- Ludwig Binder: The Church of the Transylvanian Saxons. Martin Luther Verlag, Erlangen 1982, ISBN 978-3875130294 .

- Friedrich Teutsch : History of the Protestant Church in Transylvania. Vol. I and II. Sibiu 1921 and 1922 respectively.

- Michael Weber: The Reorientation of the Protestant Churches in Romania 1990–1996 . In: Church in the East: Studies on Eastern European Church History and Church Studies . On behalf of the Eastern Church Committee of the Evangelical Church in Germany and in connection with the Eastern Church Institute of the Westphalian Wilhelms University of Münster, ed. by Günther Schulz, Volume 40/41, Göttingen 1999, pp. 138-151.

- Ulrich Andreas Vienna, Friedrich Müller-Langenthal: Life and service in the Evangelical Church in Romania in the 20th century. Monumenta Verlag, Sibiu / Hermannstadt 2002.

- Ulrich Andreas Vienna: Resonance and Contradiction: From the Transylvanian Diaspora People's Church to the Diaspora in Romania , Martin Luther Verlag, Erlangen 2014, ISBN 978-3-87513-178-9 .

See also

Web links

- Evangelical AB Church in Romania

- Evangelical Theological Faculty Sibiu

- Evangelical Academy of Transylvania

Individual evidence

- ^ Churches in Romania: Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Romania. In: lutheranworld.org . Retrieved July 23, 2020 .

- ↑ Harald Roth (Ed.): Handbook of historical sites . Volume: Transylvania (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 330). Kröner, Stuttgart 2003, ISBN 3-520-33001-6 .

- ^ Sever Cristian Oancea: The Lutheran Clergy in the Vormärz: A new Saxon intellectual elite . In: Victor Karady, Borbála Zsuzsanna Török (ed.): Cultural dimensions of elite formation in Transylvania (1770–1950) . Cluj-Napoca 2008, ISBN 978-973-86239-6-5 , p. 24–35 ( http://www.edrc.ro/docs/docs/elitform/Intregul-volum.pdf (PDF)).

- ^ Paul Milata : Between Hitler, Stalin and Antonescu: Romanian Germans in the Waffen-SS . In: Studia Transylvanica, Volume 34 . Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar 2007, ISBN 3-412-13806-1 , pp. 336 .

- ^ Johann Böhm: National Socialist Indoctrination of Germans in Romania 1933-1944 . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-57031-9 , pp. 71–92 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- ^ Johann Böhm: National Socialist Indoctrination of Germans in Romania 1933-1944 . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2008, ISBN 978-3-631-57031-9 , pp. 98-107 .

- ^ Johann Böhm: Episcopal Vicar Friedrich Müller as Resistance? In: Johann Böhm (Ed.): The synchronization of the German ethnic group in Romania and the “Third Reich” 1941-1944 . Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 978-3-631-50647-9 ( blogspot.com [accessed on August 6, 2017]).

- ↑ Dietmar C. Plajer: The Reformation minority churches in Romania from 1944 to 1989 . In: Peter Maser, Jens Holger Schjørring (ed.): Between the millstones: Protestant churches in the phase of the establishment of communist rule in Eastern Europe . Martin-Luther-Verlag, 2002, ISBN 978-3-87513-136-9 , pp. 210 .

- ^ Rada Cristina Irimie: Religion and political identification in Communist Romania. 2014, accessed August 6, 2017 .

- ^ Securitatea şi Biserica Evanghelică - Securitate and Evangelical Church. In: Half-yearly publication - hjs-online. January 19, 2011, accessed August 6, 2017 .

- ↑ Details and individual references in the corresponding articles on Friedrich Müller-Langenthal and Albert Klein .

- ↑ Michael Weber: The Reorientation of the Protestant Churches in Romania 1990-1996 . P. 146ff.

- ↑ Christoph Klein: About requests and understanding. Twenty years in the episcopate of the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Romania 1990 - 2010 . Schiller Verlag, Hermannstadt, Bonn 2013, ISBN 978-3-944529-19-6 .

- ^ Bishop D. Dr. Christoph Klein will retire in 2010. Evangelical Church AB in Romania, December 16, 2009, archived from the original on November 18, 2011 ; accessed on December 18, 2016 .

-

↑ Guib, noul Episcop al Bisericii Evanghelice din Romania . ( Memento of the original from July 6, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. Citynews (Sibiu local medium), November 27, 2010, accessed on December 18, 2016 (Romanian). Lutheran ministry. Journal of the Martin Luther Association in cooperation with the DNK / LWB , volume 47, 2011, issue 1, page 19

- ^ Thomas Schmid: Romania - The lateral entry. In: Berliner Zeitung (online), October 22, 2014.

- ↑ Good luck and good luck, Klaus Johannis! Website of the Evangelical Church AB in Romania (www.evang.ro), accessed on April 11, 2018.

- ↑ 12 apple trees for a clear word. 2017, accessed August 6, 2017 .