Dinant massacre

On August 23, 1914, German troops carried out the Dinant massacre in Belgium , killing 674 civilians . At the same time around 1100 to 1300 of the 1800 houses in the city were destroyed. The action of the German troops at the beginning of the First World War took place in the course of their march through the previously neutral neighboring country.

From August to October 1914 in Belgium 5521 civilians through killings and targeted destruction of villages killed, the massacre of Dinant was the largest of these outbreaks of violence German soldiers against civilians. The German officers and soldiers justified their actions with alleged attacks on civilians or guerrillas ( franctireur ), the Belgians denied such attacks vehemently.

The massacre is hardly present in the historical consciousness of the Germans. As far as the outbreaks of violence by German troops against Belgian civilians at the beginning of the First World War are remembered, the events of Dinant are overshadowed by the acts of violence in Leuven . In the English-speaking world, the massacre contributed to the emergence and spread of the propaganda term Rape of Belgium ( desecration of Belgium ).

A memorial in the city center commemorates the fate of those killed in Dinant. In 2001 the Federal Republic of Germany apologized to the descendants of the victims at the time.

context

Campaign planning in the west

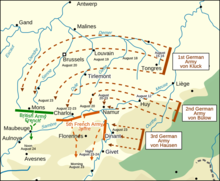

The Schlieffen Plan of 1905 provided a strategic concept for the General Staff of the Prussian Army to avoid a protracted two- front war between Germany and France and Russia . According to this plan, France was to be defeated in a few weeks, in order to then lead the military forces against Russia into the field and defeat it.

Belgium's neutrality had been contractually agreed and guaranteed by the major European powers since the 1830s . However, the modified Schlieffen Plan provided for this neutrality to be disregarded in order to bypass the French armies with a large pivoting movement in the north when war broke out and then to face them from behind. The German military planners did not expect any sustained resistance from the Belgians to the invasion and occupation of their country associated with the plan .

Franctireurs

Many soldiers of the German army marched into France and Belgium with the expectation of a fight not only against regular troops having to, but also against civilians disguised them or as snipers from the ambush would attack. This expectation was based on experiences with so-called Franctireurs in the Franco-German War of 1870–1871 . The memories of it were passed down many times in military circles. Even before the beginning of the war and before crossing the national borders, the troops were prepared for this possible danger - "Due to their training, German officers firmly expected resistance from the civilian population in a coming war and regarded this as a crime".

During the first weeks of the World War, unchecked news of such incidents quickly spread within the army and in the German press. Letters from soldiers to relatives and friends often reported that Belgian civilians were bombarded by German troops. Even Harry Kessler thought that the Belgians would a people's war conduct:

“But it is terrible that you have to keep punishing so many civilians for firing on our people; that whole towns are burned and destroyed. That gives (sic!) Horrible, shocking pictures and experiences. "

On August 9, 1914, Kaiser Wilhelm II and Karl von Bülow , Commander-in-Chief of the 2nd Army , condemned the alleged People's War of the Belgians against the German troops.

In principle, the Hague Land Warfare Regulations provided for improved protection for civilians. The leadership of the German military, however, was not willing to include this in the instructions for their officers. In the " Field Service Regulations " of 1908 there was no reference to the international agreement. Instead, special precautionary measures were called for against possible attacks by the civilian population. This included threats of punishment against residents, taking hostages or keeping the house entrances open. Although the land warfare order granted the population a right of resistance , the field service order in fact denied this right. Instructors of officers openly pointed out that the German view contradicts certain regulations of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations, but that this view should be given priority, because otherwise the door and gate would be opened to the “Franktireurkrieg”.

Invasion of Belgium

With its ultimatum to Belgium , the German Reich demanded free passage for its troops on August 2, 1914. Belgium saw this as an attack on its neutrality , independence and existence. King Albert rejected the ultimatum on August 3rd. On the night of August 4, German troops crossed the border and advanced into Belgian territory . Within a few weeks, the number of German soldiers in Belgium or crossing it grew to a million men, an invading army of unprecedented proportions.

Despite its clear numerical inferiority, the Belgian army offered resistance to such an extent that the invaders were surprised. It could not prevent the occupation of the country, but delayed the implementation of the German campaign plans. The battle of Liège (August 4th to 16th, 1914) developed into the first point of crystallization of the Belgian resistance. Even if this battle did not prevent the German march through, it was of immense importance - both for the Belgians and for their opponents. It became clear to the Belgians that their fortresses - the Liège fortress ring was considered impregnable - did not offer sufficient protection against destruction by the most modern military equipment such as the " Fat Bertha ". Many German soldiers and officers denied the legitimacy of the Belgian army's resistance. Anger and anger at this resistance, as well as the idea of ubiquitous Franctireurs, led to the demonization of the population of Belgium.

Destruction and killings of civilians

During the weeks of war of movement in Belgium, German soldiers committed acts of violence against civilians in many places. A total of 484 such incidents, with a total of 5521 deaths, were directly related to military combat operations or panic reactions by German soldiers (including as a result of self-fire ). In many cases, such outbreaks of violence were retaliatory measures for setbacks, losses or alleged franchiseur attacks. The civilians perished in individual and mass shootings, as human shields , as hostages or in the course of expulsions , deportations and arson .

Riots with more than 100 deaths each occurred in Soumagne (August 5, 118 dead), Mélen (August 8, 108 dead), Aarschot (August 19, 156 dead), Andenne (August 20, 262 dead) , Tamines (August 22, 383 dead), Ethe (August 23, 218 dead), Dinant (August 23, 674 dead), Löwen (August 25, 248 dead) and Arlon (August 26, 133 dead) . Houses were almost always destroyed, often by deliberate arson. In the course of the riots with more than 100 dead, a total of 4,433 buildings were destroyed. “During these first weeks of the war, the German high command led a terror regime against the civilian population”, judges the Belgian historian Laurence van Ypersele.

Massacre and destruction of the place

First skirmishes in Dinant

Dinant had around 7,000 inhabitants in August 1914. This made it the second largest city in Namur Province . The place is on the Meuse , about 30 kilometers south of the provincial capital Namur (where the Meuse and Sambre meet), and only 20 kilometers from the French border at Givet . The town was strategically important for the crossing of the Meuse. The river flows here in a northerly direction, across the former route of the Germans. Often only a few hundred meters wide, the city stretched around four kilometers on the east bank of the river. To the east they bordered steep cliffs; the west bank opposite the city was covered in many places with hedges and forests.

Like many of his Belgian counterparts, the mayor of Dinants publicly called on residents at the beginning of August 1914 not to take part in military clashes and to hand over weapons and ammunition to the police. As a precaution, he also forbade meetings and demonstrations in support of the Belgian army and the Allies .

After the numerically significant German invasion of Belgium had become evident, the French 5th Army under Charles Lanrezac had received permission to advance into Belgian territory, where they took up positions in the area of the Sambre-Maas triangle. The Meuse crossing at Dinant was defended by troops of the French I. Corps under Louis Félix Marie Franchet d'Espèrey .

The German 3rd Army was under the command of Max von Hausen . The mobile Saxon army was combined in the association. The 3rd Army was ordered to cross the province of Namur to the west and fight for crossings over the Meuse. Initially, it did not encounter any significant resistance. On August 15, 1914, an advance guard tried to capture and secure the strategically important bridge in Dinant. It was repulsed by French troops defending the city. In this battle, Charles de Gaulle , who belonged to the French units with the rank of lieutenant , was wounded. The specific acoustics of the site, in particular the echoes that were thrown back from the cliffs, and the fact that the residents of Dinant cheered the success of the French soldiers lively, may have given the Saxon troops the impression that Belgian civilians were together with the French Soldiers fought against them.

A second incident occurred in the course of the Battle of the Sambre , which began on August 21, on the night of August 22, 1914. A motorized troop of pioneers and riflemen entered Dinant using the Strait of Ciney . He killed seven civilians and set 15 to 20 houses on fire with torches. His advance was based on an ambitious order: “ Das Batln. takes possession of Dinant, [...] drives out the occupation and destroys the place as much as possible. “The commander of the 46th Infantry Brigade was Major General Bernhard von Watzdorf . The descent into the village was initially without surprises. Inside the city, members of the battalion saw light in a café and threw a hand grenade into it. The soldiers were then taken under fire from all sides. They offered an easy target with their torches. The command then complained about 19 dead and 117 wounded. Neither during the night nor in subsequent investigations could it be made out who had taken the German troops under fire - civilians (as claimed by the Germans), French soldiers or German army personnel by fire. However, the outcome of the attack confirmed the impression that Dinant was a nest of Franctireurs.

Conquering the city

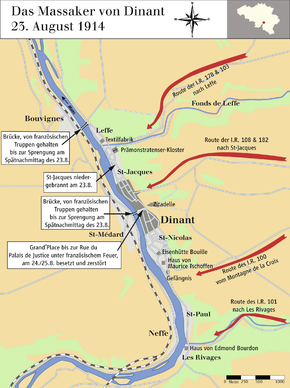

The main attack and the capture of Dinant took place on August 23, 1914. From that morning the Saxon 23rd and two regiments of the 32nd Division , covered by artillery fire , advanced in four large trains on Dinant and its suburbs.

- The infantry regiments 103 and 178 rose north of Dinant towards Leffe , and Devant-Bouvignes.

- Infantry regiments 108 and 182 reached the city center from the plateau east of the city.

- The 100 Grenadier Regiment descended from the Montagne de la Croix in the direction of Saint-Nicolas.

- In the south, the 101st Grenadier Regiment moved towards Les Rivages.

French troops kept on the west bank. They covered the German conquerors with gunfire and artillery. In the late afternoon of August 23, they blew up the Bouvignes bridge and the main bridge between Dinant and Saint-Médard. In the evening they withdrew towards the French border, which is around 15 kilometers south.

Procedure in the north of Dinant

Those German soldiers who advanced to Leffe had orders to search the steep bank for Franctireurs and to shoot any suspects they could find. Unarmed men and those whom the German soldiers did not know whether they had used weapons were also shot as they ran away. Men of the 3rd Company of the 178th Infantry Regiment were supposed to "clean" the village of Leffe of irregulars. Despite the shelling by Franctireurs, which the regiment was exposed to according to its own statements, it had no casualties or wounded. The German soldiers advanced from house to house in Leffe. They executed men who were found with weapons.

A textile factory and a Premonstratensian monastery were the most striking buildings in Leffe. In the course of the house searches, many residents were brought to the monastery church. Others fled there independently. Around 10 a.m. German soldiers singled out 43 men from the group held there and shot them. The monks were alleged to have shot at the Germans, for which they were fined 15,000 francs . Women and children were locked in the monastery church for days.

Another part of the Leffes population had taken refuge in the basement of the textile factory. Among them were the factory director Rémy Himmer (also Vice- Consul of Argentina ), his relatives and workers from Leffe. They surrendered to the surprised Germans around 5 p.m. Women and children were taken to the monastery, Himmer and 31 men were fusilized . The factory was burned down.

Operations in the city center

Infantry regiments 108 and 182, together with artillery regiments 12 and 48, made their way to the center of Dinant. They used the same road that the motorized squad of engineers and riflemen had taken on the night of August 22nd. On their way they came under heavy fire from the French troops. Members of the two Saxon infantry regiments executed many civilians, including 27 men who had fled to a bar. Much of the inner city district was burned down.

The 100 Infantry Regiment chose a steep descent route and reached the southern part of the city via Saint-Nicolas. This group also committed acts of violence against civilians. Hand grenades were thrown into many house cellars. In the city the soldiers crossed the central large square to get to the Meuse. They used civilians as human shields to protect themselves from French bullets. Civilians were rounded up. One of the assembly points was the Bouille ironworks, another the city prison. In the afternoon, German soldiers singled out 19 civilians from the group of people detained in the ironworks and shot them. Then German soldiers drove the rest of the civilians from the ironworks to the central square. A little later, men and male youths were singled out. They had to line up near the city prison along a wall that separated the property of local prosecutor Maurice Tschoffen from a street and were shot. 137 people died in this execution. The firing squad's shots apparently prevented an impending massacre in the immediately adjacent Dinant prison. There women and children had already been separated from men and execution threats had been issued. The noise of the shootings near the prison caused confusion within the detention center and the already singled out men were returned to their families.

Violence in the south of the city

The members of the 101st Infantry Regiment advanced along with the 3rd Engineer Company on the southernmost route. In the suburb of Les Rivages, they searched houses and rounded up civilians as hostages. They also began building a pontoon bridge over the river. After around 40 meters of this makeshift bridge had been completed, the German soldiers involved in the construction came under French fire. The Germans assumed that Franctireurs had shot at them. They sent Edmond Bourdon, a judicial officer for the local court, to the west side of the river in a boat to warn the alleged irregulars that hostages would be shot in Les Rivages if there were any further fighting. When Bourdon rowed back to Les Rivages, he was shot at and injured by German troops. After more shots from the west side of the river, the German soldiers carried out the threatened shooting of hostages. Bourdon himself and other members of his family were among the 77 people executed. More than half of the victims were old people, women, children and babies. The shootings took place in front of the judge's house. The executions continued on the west bank of the Meuse when the 101st Infantry Regiment reached nephew there. 86 residents of this southwestern suburb of Dinant were killed.

Acts after August 23, 1914

In the days that followed until August 28, German soldiers pursued Belgian civilians and shot at least 58 people. Buildings were systematically burned down, including initially spared facilities such as the post office, bank building, the collegiate church, the town hall and the monastery. The city was thoroughly pillaged and devastated. Around 400 people from Dinant and its neighboring villages were deported to Germany and remained imprisoned in the Niederzwehren POW camp near Kassel until November 1914 .

Victim record

Of those killed in the Dinant massacre, 92 were female. 18 of them were older than 60 years, 16 under 15 years old. Of the 577 men, 76 were older than 60 and 22 were younger than 15 years old. The oldest victim died at the age of 88, 14 children were younger than five years. The age of the youngest victim is given as three weeks.

consequences

Official memoranda

A Belgian commission of inquiry dealt with violations German troops during the invasion of Belgium and published on the Department of Justice in Le Havre reigning Belgian government in exile down a set of reports. In her statement of January 1915, she first took a comprehensive position on the events of Dinant. The acts of violence at Dinant are also mentioned in the Bryce Report of early May 1915, which had a considerable journalistic impact as a report on German atrocities during the World War .

On May 10, 1915, the German Reich reacted to the accusations made by Belgium and the Allies with the memorandum, known as the “ White Book ”, The conduct of the Belgian People's War in violation of international law . This justification for the actions of German troops spread the thesis of a people's war in which Franctireurs play an essential role. The Dinant events have been dealt with extensively in a separate section. The civil and military authorities involved in the preparation of the White Paper compiled the testimony with high pressure after reports on the events of Dinant became known internationally in the winter of 1914/15. The statements reproduced in the “White Paper” were largely manipulated and embellished; contradicting witness statements were not allowed to be printed.

The Belgian government's commission of inquiry responded to the white paper by creating a “gray book”. In this approximately 500-page publication, which came out in April 1916, the German thesis of a Belgian people's war was initially refuted. In its appendices, the gray book then dealt with the German descriptions of various crime scenes and acts of violence, including the mass shooting of Dinant. In particular, statements by Belgian civilians and German prisoners of war were used. The gray book also contained detailed lists of victims. Shortly after the end of the First World War, the German military historian Bernhard Schwertfeger summed up the effects of the gray book in front of members of the Foreign Office : While the white paper was "not very useful for our cause", the Belgian gray book with its "downright devastating information" about atrocities " in Aerschot […] in Andenne, in Leuven and above all in Dinant […] ”made a considerable impression worldwide.

Further statements in the war years

In addition to the official memoranda, there were other journalistic statements on the events in Dinant. Adolf Köster , editor of the SPD central organ Vorwärts and the Hamburger Echos , and Gustav Noske , SPD member of the Reichstag , editor-in-chief of the Chemnitzer Volksstimme and defense expert of the party, wrote a pamphlet in 1914 that shared the position of the German army and left no doubt about it that civilians in Belgium had fought against German troops. In it they also defended the executions of civilians: "Besides, neither soldiers nor officers deny that, according to the bitter law of war in Leuven as in Dinant, the innocent suffered with the guilty."

Cardinal Désiré-Joseph Mercier , who during the war emerged as a decided opponent of the German occupation, took the opposite point of view. He mentioned the executions in Dinant and other Belgian cities in his pastoral letter " Patriotisme et Endurance ", which was read out at Christmas 1914 and denied the German view of the invasion and called on the Belgians to love the country and to be steadfast. In 1916, Ernest Evrard also took the Belgian point of view in his 16-page brochure, which was illustrated with many drawings, denounced the acts of the " Teutons " and the " barbarians " and named the German officers who, in his opinion, were responsible. Maurice Tschoffen was one of those who were deported from Dinant to Kassel and interned there in the Niederzwehren POW camp. The lawyer questioned witnesses to the events of Dinant in the camp. After his return in 1915 he carried out further examinations in his hometown. His report on the destruction of Dinant appeared in the Netherlands in 1917 . He was concerned not only with refuting the thesis of Belgian civilians fighting, but also with naming all those killed.

Prosecution

The Treaty of Versailles with its penal provisions (Articles 227 to 230) provided for German war crimes to be punished by Allied criminal courts. On February 3 and 7, 1920, the Allies therefore demanded the extradition of around 900 people, including officers of all ranks up to Field Marshal , NCOs, ordinary soldiers and civilians including the former Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg . The German public reacted indignantly - driven by a campaign by the German National People's Party , patriotic associations and representatives of the Reichswehr Ministry working behind the scenes . On February 17, 1920, the Allies gave in and now demanded the indictment of the suspects in Leipzig before the Imperial Court . On May 7, 1920, they submitted a list of 45 names to the German authorities, which became known as the "sample list" - the Allies wanted to use the proceedings against these persons to determine the extent to which Germany would comply with international criminal law . 15 suspects were found on this list at the request of Belgium. However, there was no one among them who was held responsible for the acts of Dinant, although Belgium originally wanted to hold 22 German military personnel accountable for the Dinant massacre.

Belgium was quickly dissatisfied with the Leipzig trials . Similar to the French, who sentenced more than 1,200 Germans in absentia by December 1924, Belgian courts passed judgments in absentia . On May 9, 1925, a Belgian court martial in Dinant sentenced several German officers for the crimes in the small Belgian town. The Reichsgericht took up these cases, but in November / December 1925 rejected all allegations. It upheld the Franctireur thesis in the Dinant case as well. One of the accused was Colonel Johann Meister , in August 1914 commander of the 101st Infantry Regiment. The Belgian indictment accused him of the "systematically inhuman behavior of his troops in the period from August 19 to 27, 1914" and of ordering the execution of civilians in Les Rivages on August 23, 1914. The court in Leipzig found that German soldiers had been shot at by civilians in Dinant, including women and children. Although some witnesses stated that the executed hostages included women and children, the German court saw no reason to convict Meister. It stated: “According to this there are no facts from which it can be concluded that the killing was unlawful. In addition, an order from the accused to shoot those civilians has not been proven. ”In its judgment, the German court referred to German investigations from 1915 for the White Paper and another from 1920 that exonerated Meister; The order for executions in Les Rivages was not given by him, but by one of his subordinates.

Cultures of remembrance: forms and conflicts

In Dinant, public and collective forms of remembrance established themselves immediately after the end of the First World War . In December 1918, the local lawyer Edouard Gérard publicly read out an “oath” on behalf of the city council . This condemned the thesis of the Franctireurs and called for the perpetrators of the massacre to be punished. The ceremony was repeated in memory of the liberation of the city by British and American troops. Cardinal Mercier gave a speech in Dinant on August 23, 1919, the fifth anniversary of the massacre. He emphasized that Belgium was the most tried and heroic country in the world, and of the Belgian cities Dinant was the bravest in his grief. The residents of Dinant remembered the executions in many places in their place, and a kind of “ Stations of the Cross ” was established which connected the execution sites. Some of the local memorial sites were motifs from contemporary postcards .

The popular culture of remembrance and the propaganda of the military successes of German troops in Germany included so-called Vivat tapes during the war years . Proceeds from the sale of these textiles went to the German Red Cross . Several of these anthologies were dedicated to crossing the Meuse in Dinant. There is no evidence of clashes with the civilians, either in the volume that Joseph Sattler illustrated or in another. The remembrance literature of German officers, however, presented the thesis of the Belgian Franctireurs openly. General Max von Hausen, commander of the 3rd Army, described in his war memoirs published in 1922 the bitter resistance of civilians in Dinant, in which women and children were also involved. Hausen defended the city's shelling, arson, executions of gun-bearing civilians and hostage shootings. Because of the Belgian People's War, which was also shown in Dinant, these acts are not violations of international law.

In Dinant, the city administration began in the mid-1920s to design the various memorial sites according to uniform principles. In addition, a memorial for the victims of the war was erected in front of the town hall. The inauguration took place on August 27, 1927. The ceremony was attended by Crown Prince Leopold , Minister of War Charles de Broqueville and French Minister of Pensions, Louis Marin . Speakers at the event condemned the fact that Germany was still sticking to the Franctireur thesis and the claim that a people's war had taken place in Belgium in August 1914. A few days later, a memorial to the French soldiers who died in the fighting for Dinant was inaugurated. Guest of honor Marshal Pétain called Belgium "the vanguard of Romance ". Friedrich von Keller , German ambassador to Belgium , protested sharply against inscriptions denouncing the "Teutonic rage" and the "German barbarism". Right-wing and Catholic newspapers in Germany joined the protest and criticized a resurgence of the "horror legends" and "war psychoses". Many newspapers repeated the claim that civilians, including children in Dinant and other Belgian towns, had taken part in the fighting against the German soldiers. The German Reichskriegerbund "Kyffhäuser" and the German Officers Association (DOB) saw attacks on the honor of German soldiers in the celebrations in Dinant . In particular, the DOB which urged national government to protest to the Belgian Government.

In 1927 there was another crisis in German-Belgian relations. The trigger was the publication of the publication The Belgian People's War , already written in 1924 by the Würzburg international lawyer Christian Meurer . The study was published by the 3rd subcommittee of the Reichstag committee of inquiry as the 2nd volume in the series on international law in war . The now official document dealt with the German invasion of Belgium and denied all allegations of the Belgians against the German army. Meurer argued like the German White Paper of 1915: Belgian civilians including priests , women and children had fought the invading army on a large scale. The German reaction to this was legitimate. Meurer had already submitted an apologetic work in 1914 : He was the author of the essay The People's War and the Criminal Court on Lions . Opposing opinions within the subcommittee, in particular the critical positions of the Social Democrats Paul Levi and Wilhelm Dittmann , who harbored doubts about the innocence of German troops, had been completely ignored. The first comprehensive Belgian counter-writing was written by Professor Fernand Mayence (1879–1959) from Löwen. It appeared in 1928 and developed the thesis that the German soldiers fell victim to a mass suggestion in the early weeks of the war . The font was translated into German and distributed in a number of 15,000 copies, 7,000 of which went to professors and high school teachers . The Social Democratic Forward joined Mayence's reasoning. Maurice Tschoffen and Norbert Nieuwland wrote an answer to Meurer's report for Dinant. It was also translated and by June 1930 had a circulation of 200,000 in Germany. Her theses were received positively by social democratic and pacifist magazines. In March 1929, the Reich Ministry of Post tried to limit the scope of the Tschoffen and Nieuwland brochure by imposing a ban on transport. Thereupon pacifist associations distributed the writing on their own.

The controversy over memory hit tourism in the early 1930s . The cities of Dinant and Aerschot took legal action against Baedeker-Verlag in 1932/33 . The latter had adopted the German thesis of the Belgian Franctireur War in his Belgium travel guide. After legal disputes, the publisher agreed to print a new version with a neutral depiction of the events - until then, the sale of both the German and English-language versions of the travel guide was prohibited in Belgium. The Ministry of Defense and the Foreign Office took over the court costs of the publishing house. The dispute between the two Belgian cities and the German publishing house was received intensely in the Belgian and German newspapers - with diametrical signs.

In the interwar period , a central memorial commemorating the Belgian civilian victims formed the keystone of the dispute over memories of the events of August 1914. A first design by Pierre De Soete (1886–1948) envisaged a 50-meter-high obelisk . The memorial was also to contain parts of an inscription that was initially intended for the rebuilt library in Leuven , but was not installed there after violent international disputes because it denounced a "furor teutonicus". The announcement of the plans for such a memorial in Dinant, which were being promoted by a group led by Edouard Gérard and the mayor of Dinant, Léon Sasserath, again sparked tensions between Germany and Belgium. It was also controversial within Belgium because of its accusatory inscription. Even local notables such as Edouard Gérard and Maurice Tschoffen distanced themselves from this project for reasons of state . Due to the clashes, the monument turned out to be smaller than planned, but it was still 25 meters wide and 9.50 meters high: in the middle there was no obelisk, but a hand carved from stone with two fingers stretched out to take an oath - one Remembrance of the public oath in Dinant in 1918. It was flanked by a wall with a railing bearing the inscription “Furore Teutonico”. The names of the Belgian places where civilian massacres had occurred in August 1914 were recorded on the outer pillars. Plaques on the wall listed the names of all 674 Dinant massacre victims. The memorial, which is located on the Place d'Armes in the immediate vicinity of the Mur Tschoffen , was inaugurated on August 23, 1936. Dignitaries from politics, clergy and society in Belgium and France stayed away from the event, the memorial was seen as a disruptive factor in the uncertain Belgian neutrality in the vicinity of a Nazi Germany willing to expand . After the Wehrmacht invaded Belgium, it was destroyed by the Germans in May 1940.

The study “Der Fall Löwen” by Peter Schöller , which appeared simultaneously in German, French and Flemish in 1958, caused a change in perspectives in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany . Schöller analyzed the sources and the genesis of the German "White Paper" from 1915. He showed that the thesis of the People's War and the Belgian Franctireurs was based on numerous manipulations. Schöller's study found recognition among German and Belgian historians. The same was true for journalism in these countries. Even German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer , German President Theodor Heuss and German Foreign Minister Heinrich von Brentano praised the book. The 70-page publication, however, concentrated on the events in Leuven, not dealing with the massacres in other parts of Belgium. For other important acts of violence - including those of Dinant - other detailed investigations were planned, but they did not materialize. A number of WWI veterans rejected Schöller's study, sticking to the thesis of the Belgian Franctireurs. In West German school books of the 1970s, the shootings in Leuven were dismissed as Belgian war propaganda. In its 20th edition (1996), the Brockhaus Encyclopedia also claimed that the term “Franctireurs” denoted civilians who fought behind the front against the German armies in France and Belgium in 1870/71 and 1914.

In the summer of 2014, a dispute arose between the Marburg city administration and the Marburg Jäger comradeship over the demolition of a war memorial honoring the “Marburg Jäger” who took part in the 1914 massacre in Dinant .

In Dinant there were regular church services on August 23, dedicated to the memory of the victims of the massacre. On the town hall of Dinant a memorial commemorates the victims of the massacre and the victims of the Second World War , on the Mur Tschoffen (Rue Daouest) there is a memorial to the v. a. refers to the 116 citizens shot at this wall. There are still a few more commemorative plaques in the streets of Dinant, for example in Rue St. Pierre. In the citadel there is a detailed exhibition about the events in August 1914.

The Federal Republic of Germany apologized for the massacre in 2001, and Walter Kolbow , Parliamentary State Secretary in the Ministry of Defense , asked for forgiveness on the spot for the injustice committed by Germans. On the centenary of the events, commemorative services were held in Dinant, in which the King of the Belgians also took part. Among other things, another memorial was erected to replace the one that was destroyed in May 1940. It has the shape of a walk-in stele that protrudes from the ground and is laid across . The shooting locations and the names of the victims are engraved in this shape. On September 13, 2013, the German Chancellor Angela Merkel received an invitation from Mayor Dinants to attend the festivities, which she turned down.

Artistic processing

Visual arts

The Dutch painter and caricaturist Louis Raemaekers (1869–1956) stayed in Belgium in August 1914 and made a large number of drawings with which he sharply denounced the violence and domination of the Germans in Belgium. His works were extremely widespread in books, as slides , as picture postcards and as reprints in newspapers of neutral countries and states that were waging war against Germany, and made the artist famous. One of his atrocity drawings was titled The Massacre of the Innocents - an allusion to the child murder in Bethlehem . It shows how horrified women and girls who have to watch their husbands being shot in Dinant are brutally pushed back with rifle butts . Another drawing entitled Peace reigns in Dinant shows a pipe-smoking German soldier in the foreground in the ruins of Dinant. A pile of corpses can be seen in the background.

The American painter and draftsman George Wesley Bellows thematized the mass shootings of civilians in Dinant in a lithograph and an oil painting that he created in the spring of 1918 as part of his War cycle . This dealt with crimes of German troops in Belgium. Corresponding reports by Brand Whitlock (1869–1934), the American ambassador to the Belgian government , as well as passages of the Bryce Report had inspired Bellows to do so.

Fiction

Arnold Friedrich Vieth von Golßenau took part in the conquest of Dinant as an officer. Under the artist name Ludwig Renn , he processed his experiences in his novel Krieg , which was published by the Frankfurt Societäts-Druckerei in 1928 . The narrator was not an eyewitness to Franctireur activities. However, he attributed gunfire to his unit to Belgian civilians and was convinced of the truth of the rumors of violent Belgian riot activity.

In an essay in several parts, which appeared in 1929 in Die Linkskurve , the organ of the Association of Proletarian Revolutionary Writers , Renn explained the background to the development of his anti-war novel. In doing so, he clearly distanced himself from the Franctireur thesis, which he had also repeated in his novel. He admitted that in August 1914 he had succumbed to a delusion . "But we believed we were being shot at by residents and shot dead civilians en masse."

exploration

Research and memory in Germany

In his doctoral thesis, published in 1984, the historian Lothar Wieland examined the question of the supposed Franctireur War in Belgium and public opinion on this war in Germany. His aim was not only to record, classify and evaluate German statements in politics and journalism. He also examined the Belgian positions on this question, not least in order to be able to question the thesis on the "Franctireur War", which was widespread in Germany from 1914 to the 1950s. The different perceptions of the Dinant massacre are addressed, but Wieland lacks a description of the massacre.

The war crimes committed by German soldiers in occupied Belgium during the First World War have hardly reached the historical consciousness of the Germans; in many cases they are overlaid by memories of German war crimes, crimes against humanity and genocide in the Second World War . The best known of the violent crimes against Belgian civilians is the destruction of Lion. The devastation of this university town, with its cultural treasures and its library, provoked severe criticism of the German warfare as early as the First World War. The events in Dinant never received this level of attention, although significantly more civilians were killed there.

Belgian and international studies

The historians John N. Horne and Alan Kramer deal in their 2001 study German atrocities, 1914. A history of denial , which has been available in German translation since 2004, with the atrocities committed by German soldiers in occupied Belgium during the First World War. They go into detail on the Dinant massacre and the different perceptions of what happened in Belgium, Germany and other countries, both during the war years and afterwards. The two historians work out that in Dinant - as in Belgium as a whole - there was no people's war against the German invaders and that Franctireur activities only occurred occasionally. However, they admit to the German soldiers that they assumed they were attacked by Belgian civilians - the two historians assume a collective delusion of the German troops that guides the action.

This line of reasoning can be found in a similar way in an essay by Aurore François and Frédéric Vesentini published in 2000. The authors, both historians at the Université catholique de Louvain , dealt in particular with the causes of the Dinant and Tamines massacres. Typical characteristics of invasive wars had come to the collective people's war madness: privation and suffering as well as anger and alcohol-related intoxication of many soldiers had contributed to the outbreak of violence against civilians, as did the stimulating effect of gun possession. Obedience to superiors and commands as well as group dynamic processes were also responsible.

Horne and Kramer were able to base their explanations on the culture of remembrance in Dinant on a dissertation that the Belgian historian Axel Tixhon wrote in 1995 on the history of commemoration of the massacre.

In the UK teaching historian Jeff Lipkes denies that the violence was a collective delusion in Belgium result. Rather, his thesis is that they were ordered and actively promoted by their military superiors. In Belgium, a terror campaign was deliberately staged to intimidate the civilian population. The events in Belgium were also a test run for the mass crimes committed by National Socialist Germany during World War II. Reviewers questioned the explanatory value of Lipke's theses. In the context of his study published in 2007, the author devotes around 120 pages of dense descriptions of the massacre in Dinant and its suburbs , which are primarily based on Belgian witness statements from the war and post-war years and on documents from Belgian archives . Lipkes also compares the events in Dinant with the crimes of the SS in Eastern Europe.

attachment

literature

- Aurore François, Frédéric Vesentini: Essai sur l'origine des massacres du mois d'août 1914 à Tamines et à Dinant . In: Cahiers d'histoire du temps présent . No. 7 , 2000, pp. 51-82 .

- Gerd Hankel : The Leipzig trials. German war crimes and their prosecution after the First World War . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2003, ISBN 3-930908-85-9 .

- John N. Horne, Alan Kramer: German war atrocities 1914. The controversial truth. From the English by Udo Rennert . Hamburger Edition, Hamburg 2004, ISBN 3-930908-94-8 , pp. In the original as .

- John N. Horne, Alan Kramer: German atrocities, 1914: a history of denial. Yale University Press, New Haven, CT 2001, ISBN 978-0-300-08975-2 .

- Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals. The German Army in Belgium, August 1914 . Leuven Univ. Press, Leuven 2007, ISBN 3-515-09159-9 .

- Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914. The question of the Belgian “Franktireur War” and German public opinion from 1914 to 1936 (= studies on the continuity problem of German history . Volume 2 ). Lang, Frankfurt am Main a. a. 1984, ISBN 3-8204-7662-8 .

- Larry Zuckerman: The Rape of Belgium. The Untold Story of World War I . New York University Press, New York, London 2004, ISBN 0-8147-9704-0 .

Web links

- Michel Coleau: Le Sac du 23 Août 1914 . French-language article on the City of Dinant website (accessed November 3, 2012).

- Dinant - une nouvelle page d'histoire (6 May 2001) . Photo report about the event in Dinant, at which Walter Kolbow apologized for the massacre on behalf of Germany in 2001.

Individual evidence

- ↑ The literature usually assumes 674 fatalities. Deviating from Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , p. 271 - here the number 685 is mentioned.

- ^ Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , p. 271.

- ↑ Information on the destroyed buildings according to Gerd Hankel: The Leipzig Trials , p. 203.

- ↑ See John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 121.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich : War of words, battle of images . In: Die Zeit , June 24, 2004.

- ↑ Late Reconciliation ( Memento of October 10, 2004 in the Internet Archive ). In: Netzeitung , May 6, 2001.

- ↑ On the importance of Belgium in the Schlieffenplan see Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , p. 2.

- ↑ See John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 215-218.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 225. Examples of corresponding assumptions before the march order in John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 199 f.

- ↑ See Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , pp. 19-23.

- ↑ Quoted from Günter Riederer: Introduction, in: Harry Graf Kessler : Das Tagebuch 1880–1937 . Volume 5. 1914-1916, Cotta, Stuttgart 2008, p. 29 .

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 41.

- ↑ Quoted from John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 225. On the lack of implementation of protective provisions of the Hague Land Warfare Regulations in German military regulations, see John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 222–228.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 19.

- ↑ Laurence van Ypersele: Belgium in the “Grande Guerre” , in: APuZ , B 29–30 / 2004, pp. 21–29, here p. 22 ( html version ).

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 33.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 120 f.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 123 f.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 122 f.

- ↑ All death toll and destroyed buildings according to John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 636–647.

- ↑ Laurence van Ypersele: Belgium in the “Grande Guerre” , in: APuZ, B 29–30 / 2004, pp. 21–29, here p. 23 ( html version ).

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 72 f.

- ^ Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , p. 257.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 72.

- ↑ Information on the website of the Charles de Gaulle Foundation. ( Memento of the original from May 31, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Aurore François, Frédéric Vesentini: Essai sur l'origine des massacres , p. 70; Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , pp. 259 f.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 75, there also the quote.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 76.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 76-78. The German translation of the map (p. 77) for the attack on Dinant shows no involvement of the 100th Infantry Regiment, but two descent routes of the 101st Infantry Regiment. This is probably a translation error in the map from the English-language original . According to literature - including John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 - the 100th Infantry Regiment was involved in the capture of Dinant.

- ↑ On the events in Leffe see John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 78 f; Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , pp. 271-294 f.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 79 f.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 80–83; Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , pp. 304, pp. 308, pp. 315f and pp. 324-330.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 83–86. See also Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , p. 83 and Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , p. 343 f.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 86; Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , pp. 304, p. 368, and p. 375.

- ↑ Of the 577 males and 92 females, five are counted with the status “unknown”. See Norbert Nieuwland, Maurice Tschoffen: The fairy tale of the Franctireurs of Dinant. Answer to the report by Professor Meurer from the University of Würzburg , Duculot, Gembloux 1928, p. 104.

- ↑ On her cf. John Horne, Alan Kramer: German war horrors 1914 , p. 336.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 305. See the official English translation of this report: The martyrdom of Belgium. Official report of massacres of peaceable citizens, women and children by the German army , The W. Stewart Brown company, inc., Printers, Baltimore Md. [1915], here pp. 13-15.

- ↑ Bryce Report on the firstworldwar.com website (accessed October 21, 2012)

- ↑ On the white paper see John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 349–363.

- ↑ Foreign Office : The conduct of the Belgian People's War in violation of international law , [Berlin 1915]. See there the section “Belgian people's struggle in Dinant from August 21 to 24, 1914.” (pp. 115–229), which consists of a summary report (pp. 117–124) and 87 annexes (testimonies).

- ↑ On this John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 350–352.

- ↑ To this John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 355–359.

- ↑ Belgique. Ministère de la justice: Reponse au livre blanc allemand du 10 may 1915 “The conduct of the Belgian People's War in violation of international law” , Berger-Levrault, Paris 1916.

- ↑ Schwertfeger, Bernhard Heinrich in the online version of the edition files of the Reich Chancellery. Weimar Republic

- ↑ On the gray book see John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 364 f, there all of Schwertfeger's quotations. On the gray book see also Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , p. 84 f.

- ↑ Adolf Köster, Gustav Noske: War drives through Belgium and Northern France 1914 , Berlin 1914, p. 25. Explanations on this work in John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 389 f.

- ↑ On Mercier see Ilse Meseberg-Haubold: Cardinal Mercier's resistance against the German occupation of Belgium 1914–1918. A contribution to the political role of Catholicism in the First World War , Lang, Frankfurt am Main, Bern 1982, ISBN 3-8204-6257-0 . For the pastoral letter there pp. 59–73. On Mercier's pastoral letter, see also John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 396–398.

- ^ Ernest Evrard: Les Massacres de Dinant , Imprimerie nationale L. Opdebeek, Anvers 1916. ( digitized version )

- ^ Maurice Tschoffen: Le Sac de Dinant et les Légend du Livre blanc all of May 10, 1915. SA Futura, Leiden 1917 (digitized version ) .

- ↑ Gerd Hankel: The Leipzig Trials , p. 30 and p. 41–47; John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 498–504.

- ↑ Gerd Hankel: The Leipzig Trials , p. 56.

- ↑ Gerd Hankel: The Leipzig Trials , p. 205.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 517.

- ↑ Quoted from John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 518.

- ↑ Quoted from John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 518 f.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 84 f.

- ^ Aurore François, Frédéric Vesentini: Essai sur l'origine des massacres du mois d'août 1914 à Tamines et à Dinant , p. 66.

- ↑ Two photos from this memorial event.

- ↑ On the “Oath of Dinant” and the “Way of the Cross” see John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 582.

-

↑ Examples of such places of remembrance:

- Press photo of a memorial in front of a property wall

- Press photos of signs at execution sites

- The " Mur Tschoffen ", shown on a postcard

- Memorial stone on the garden wall of Edmond Bourdon's property in Les Rivages, postcard from the interwar period

- Memorial in Saint-Paul, postcard motif

- Memorial in nephew

- Memorial in Nephew, shown on a postcard

- Commemorative plaque in Dinant, postcard motif

- ↑ Illustration of another Vivat volume on Dinant including a description of the property on the website of the museum - digital (Museumsverband Sachsen-Anhalt).

- ↑ See John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 529.

- ↑ Photo of the event .

- ^ Photo of Pétain at the inauguration ceremony in Dinant . Quoted from John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 567.

- ↑ See especially Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , pp. 153–161. Furthermore, John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 566-568.

- ↑ This subcommittee included members of all parliamentary groups with the exception of the KPD . Central politicians Eduard Burlage , Johannes Bell and Paul Fleischer chaired the meeting . The panel dealt with 13 factual questions. Reports were commissioned and brought together into resolutions. Only Members of Parliament were entitled to vote on these resolutions. The resolutions were passed unanimously or the SPD members abstained. Two issues led to minority resolutions by the social democratic members. See Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , p. 129.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 555-557.

- ↑ On Mayence see the information from F. De Visscher, Fr. de Ruyt: Notice sur Fernand Mayence, Membre de L'Académie ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.1 MB) on the website of the Académie royale des Sciences, des Lettres et des Beaux-Arts de Belgique .

- ↑ Fernand Mayence: The legend of the Franktireurs von Löwen. Answer to the report by H. Prof. Meurer, by d. University of Würzburg , F. Ceuterick, Louvain 1928.

- ↑ Norbert Nieuwland, Maurice Tschoffen: The fairy tale of the Franctireurs of Dinant. Answer to the report by Professor Meurer from the University of Würzburg , Ducolot, Gembloux 1928.

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 576-579.

- ↑ Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , pp. 371–383. John Horne, Alan Kramer: German war horrors 1914 , p. 575 f.

- ↑ On the dispute over the inscription for the rebuilt library in Löwen see Wolfgang Schivelbusch : A ruin in the war of the spirits. The library of lions. August 1914 to May 1940 , revised edition, Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1993, pp. 155–168, ISBN 3-596-10367-3 . (Schivelbusch's work was first published under the title Die Bibliothek von Löwen. An episode from the time of the world wars , Hanser, Munich [including] 1988, ISBN 3-446-15162-1 ).

- ↑ illustration of the memorial ; Le Furore Teutonico , information on the Dinant City Council website.

- ↑ Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 , pp. 383-391; John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 587-589.

- ↑ Peter Schöller : The lion case and the white paper. A critical examination of the German documentation about the events in Leuven from 25. – 28. August 1914 , Böhlau, Cologne, Graz 1958; see. in addition: the acquittal . In: Der Spiegel No. 25, 1958. (June 18, 1958, online ).

- ^ Franz Petri : Introduction. On the problem of a Belgian people's war in August 1914 , in: Peter Schöller: Der Fall Löwen and the White Book , pp. 7-13, here p. 11.

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 608–615.

- ↑ Massacres cost 674 lives , Oberhessische Presse , August 4, 2014 (accessed on August 20, 2014).

- ↑ Till Conrad: Comradeship insists on their stone ( Memento of the original from August 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , Oberhessische Presse , August 5, 2014 (accessed on August 20, 2014).

- ^ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 616.

- ^ Gisbert Kuhn: Black-red-gold is blowing again over Dinant. In: Belgiuminfo.net , June 25, 2012.

- ↑ August 23rd 2014: Belgian King visits Dinant on Centenary of First World War massacre , message on Centenary News. First World War 1914–1918 (accessed July 16, 2016).

- ^ Mémorial aux victimes du 23 août 1914. In: dinant.be. Retrieved August 13, 2017 (French, website of the city of Dinant). Kevin Coyd: The fight against the might of Big Bertha. In: The Telegraph . July 4, 2014, accessed August 13, 2017 .

- ↑ Michael Müller : Silence about German guilt , in: Frankfurter Rundschau , 23 August 2014, p. 10.

- ↑ Information on his biography .

- ↑ On this John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , pp. 438–445.

- ^ Image description and image on the Project Gutenberg website .

- ^ Raemaeker's drawing on the look and learn website .

- ^ Samuel Dorsky Museum of Art : With My Profound Reverence for the Victims: George Bellows: August 13 – September 23, 2001 . State University of New York Press, p. 7 . See also the blog post Village Massacre by George Bellows from the Anne SK Brown Military Collection .

- ↑ Description of the novel on the website LeMO (Living virtual Museum Online) of the German Historical Museum .

- ↑ Ludwig Renn: War. With a documentation , Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin and Weimar 1989, pp. 16–42, ISBN 3-351-01402-3 .

- ↑ About the requirements for my book 'War' . Reprinted in Ludwig Renn: War. With a documentation , Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin and Weimar 1989, pp. 315–332.

- ↑ Ludwig Renn: About the requirements for my book 'War' . Reprinted in Ludwig Renn: War. With a documentation , p. 321.

- ↑ On Renn and his novel War see John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 , p. 579 f. The explanations by Horne and Kramer do not, however, completely agree with the plot of the novel.

- ^ Lothar Wieland: Belgium 1914 .

- ↑ Jürgen Müller: Jeff Lipkes, Rehearsals. The German Army in Belgium, August 1914. Leuven 2007 . In: Historische Zeitschrift , Vol. 288 (2009), pp. 797–801, here p. 800.

- ↑ Wolfgang Schivelbusch: A ruin in the war of the spirits , pp. 26–31.

- ↑ Gerhard Hirschfeld , Gerd Krumeich , Irina Renz in connection with Markus Pöhlmann (ed.): Encyclopedia First World War. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2003, p. 683 , ISBN 3-506-73913-1 ; Larry Zuckerman: The Rape of Belgium , p. 30.

- ^ John N. Horne, Alan Kramer: German Atrocities, 1914: A History of Denial. Yale University Press, New Haven 2001, ISBN 978-0-300-08975-2 .

- ↑ John Horne, Alan Kramer: Deutsche Kriegsgreuel 1914 .

- ^ Aurore François, Frédéric Vesentini: Essai sur l'origine des massacres , p. 81 f.

- ↑ Axel TIXHON: Les Souvenirs of massacres du 23 août 1914 à Dinant. Etudes des commémorations durant l'entre-deux-guerres , License dissertation, Université Catholique de Louvain-la-Neuve, 1995.

- ↑ Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals . See the reviews by Antoon Vrints in European History Quarterly , Vol. 40 (2010), pp. 358 f; Sophie de Schaepdrijver in The English Historical Review (2009) CXXIV (509), p. 1002 f; Maartje Abbenhuis in The American Historical Review , June 2008, Vol. 113, Issue 3, pp. 930 f; Jürgen Müller In: Historische Zeitschrift , Vol. 288 (2009), pp. 797-801.

- ^ Jeff Lipkes: Rehearsals , pp. 270 and 321.