Russian Narva campaign in 1700

|

|

This article or section was due to content flaws on the quality assurance side of the editorial history entered. This is done in order to bring the quality of the articles in the field of history to an acceptable level. Articles that cannot be significantly improved are deleted. Please help fix the shortcomings in this article and please join the discussion ! |

| date | August 19, 1700 to November 30, 1700 |

|---|---|

| place | Estonia |

| output | Victory of the Swedes |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

| Commander | |

|

|

|

The Russian Narva campaign of 1700 was a Russian autumn campaign at the beginning of the Great Northern War in the territory of Swedish Estonia . A Russian army besieged Narva to open a " window to the west " for Russia . The significantly larger, but inexperienced Russian army, however, was defeated by a strong, smaller Swedish army on their Narva campaign in the Battle of Narva . However, the Russian defeat in the campaign did not change the course of the war lastingly. Just one year later, Russian forces in the Livonia campaigns went back on the offensive.

Geopolitical framework

Europe's foreign policy around 1700 was shaped by the era of the Cabinet Wars. War was part of the political calculation of those in power and had no totalitarian character, but only served to achieve limited, often territorial goals of the potentates.

There were four great powers in Europe. This was France in the first place , followed by the newly founded Great Britain , Austria with its neighboring countries and Sweden as a Nordic great power. Russia was not included in the European cabinet system and, like the Ottoman Empire , was outside of it. Europe was divided into a smaller northern power system with the geographical center of the Baltic Sea and a larger power system in Europe's southwest with the Rhine as the geographical center of power. Both centers functioned autonomously within the overall European system, which was largely shaped by Great Britain at the time.

Early modern warfare experienced an evolution in Europe around 1700 towards an orderly and disciplined warfare with regular behavior of the combatants. The armies grew larger and larger. In the West, army sizes in battles of 50,000 to 60,000 soldiers on each side were no longer uncommon. In the north, the conditions were significantly smaller due to the smaller population. Here 10,000 to 15,000 men per side were the rule in a battle. Russia had a very large population and no problems raising large armies. It pushed towards Western Europe, sought to get a place in the cabinet system and was ready to achieve this goal by war.

prehistory

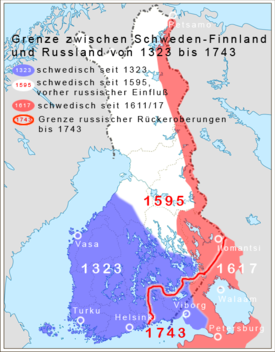

The Baltic Sea region had been contested between Denmark, Sweden, the Teutonic Order , the Hanseatic League , the Novgorod Republic and the Grand Duchy of Moscow and finally Poland-Lithuania since the Middle Ages . In the battle for the Dominium Maris Baltici , Sweden finally triumphed. It defeated Russia, which in 1617 in the Peace of Stolbowo lost the remaining access to the Baltic Sea during the Ingermanland War . Since then, the country has sought to return to the Baltic Sea. To this end, Russia began to open up to Europe in the 1650s, modernized its structures and took over European influences. An important sponsor was the young Tsar Peter I , who endeavored militarily to restore Russia's standing in Europe. For this it had to eliminate Sweden as a direct competitor.

While Russia suffered from the effects of the time of turmoil for a long time , Sweden rose to become a major European power in the 17th century and maintained so-called Dominions in the Baltic Sea region , Swedish rulers who were ruled from Stockholm. Swedish Estonia belonged to the Russian territorial claims alongside Swedish Ingermanland . Russia succeeded in conquering important Polish territories in the Northern War from 1656 to 1660 and eliminating this rival for the rule of the Baltic Sea.

An alliance of three, consisting of the Russian Empire and the two personal unions Saxony-Poland and Denmark-Norway , attacked the Swedish Empire in March 1700 , which was founded by the eighteen-year-old King Charles XII. was ruled. The opportunity for the Triple Alliance seemed favorable. The young King of Sweden seemed inexperienced and various defeats - including against Brandenburg near Fehrbellin during the invasion of Sweden in 1675 - indicated the decline of the Swedish sea and land power. Originally the Allies had agreed that Russia should open war against Sweden as soon as peace was concluded with the Ottoman Empire , if possible in April 1700. But the peace negotiations dragged on and Peter I hesitated, despite the urging of August II to join the war. An understanding with the Ottomans was only achieved in mid-August 1700, and on August 19 Peter I finally declared war on Sweden. However, he did so in complete ignorance of the fact that an important ally of the coalition, Denmark, had already ceased to exist the day before. The sea powers England and the Netherlands feared that in the face of the ailing Spanish King Charles II, a war of succession would break out between France and Austria and wanted to prevent another conflict in the northeast. When Denmark struck against Sweden in the spring of 1700, English and Dutch squadrons strengthened the Swedish fleet and Dutch-Hanoverian contingents strengthened the Swedes in the Holstein campaign . Denmark was forced to make peace with Sweden. The Saxon-Polish Livonia campaign soon got stuck in front of the great Riga fortress.

Since 1695 Peter had directed all his military activity against Azov and the Crimea , thus to the south. Now Russia's offensive power against the Baltic Sea was to be developed without sufficient time for the conversion being granted. It also became apparent that the army administration had only made inadequate preparations. No depots had been set up near the theater of war, as a result of which there was a lack of war material, food and vehicles. The season in which the campaign took place was also unfavorable: the terrain softened by autumn rains made it difficult to replenish it.

Depiction of the campaigns during the first phase of the war from the outbreak of war in 1700 to the end of the war following the battle of Poltava in July 1709.

armor

After the war, Peter spoke of the fact that the Russians started the war “like blind people”, “without knowing the opposing forces and their own situation”. An armed conflict with Sweden, for example, posed great risks for Russia. The great power status of the Nordic Kingdom of Sweden was based on the military power of a tightly organized and led army and on abundant copper and iron deposits. This allowed Sweden to maintain an efficient arms industry . In contrast, Russia's armaments apparatus was still underdeveloped and inefficient.

At the beginning of the war, the Tsar had an annual income of nine to ten million silver rubles and, on paper, commanded an army of 100,000 men. But these troops, with the exception of four regular regiments, were poorly armed and even worse trained and managed.

Russia had embarked on a phase of Western-style reforms and began to adapt its armed forces to Western standards. This was made necessary by the Strelitzen uprising a few years earlier, which was directed against Peter's internal political course and prompted him to dissolve the Strelitzen regiments. The dissolution of the Strelitzen regiments and the expulsion of the Strelitzen from the army had cost the Tsar around 30,000 professional soldiers, who he lacked at the beginning of the war. The nobility contingent was of poor quality. The Russian army was therefore in a phase of upheaval in which it broke away from the old Muscovite structures and traditions and introduced new structures. To this end, 32,000 recruits were transferred to a three-month training program. These were then distributed among 953 to 1,322 strong infantry regiments, from which a total of 27 infantry regiments were formed. To a large extent, they consisted of young recruits who had been trained according to Western European models. The reforms were not yet completed when the war began and the Russian army was not yet ready for war.

Overall, the armed forces were divided into three divisions under Generals Golowin , Weide and Repnin . The army consisted of 27 line infantry regiments, two guards regiments, two dragoon regiments and a platoon of artillery. In addition to the two dragoon regiments, the Russian cavalry also consisted of the old provincial cavalry regiments Novgorod, Smolensk and Moscow, a total of around 10,000 men. Each of the infantry regiments had two 3-pounder cannons. A total of 64 3-pounder cannons were dispatched to Narva. In all, there were 195 Russian cannons in the campaign. Of these, 64 were siege cannons, 79 regimental cannons (including 64 3-pounder cannons), 4 howitzers and 48 mortars. The Russian army was armed with Dutch rifles. Swedish sources report that of the 4,050 rifles captured at Narva, 3,800 were of Dutch origin and only 250 were Russian-made.

Another 10,500 soldiers of the Cossack army joined this new model , so that the total armed forces amounted to about 64,000 men. However, a large part of these still stood inland. Various divisions were delayed and did not reach Narva until the actual battle. Instead of 64,000 men, the Russian army in front of Narva consisted of less than 40,000 men.

Geographical space

The conquest of a stretch of coast along the Baltic Sea was Peter's declared aim in the war against the Swedes. The Baltic Sea city of Narva , now on the border with Estonia and Russia , was the target of the campaign, although it was not originally part of the closer planning of the war allies Russia, Denmark and Saxony-Poland. Narva was one of the spoils of war sought by Poland. Still, Peter believed that the safest way to secure a stretch of coast was through control of this fortress and its port.

Founded in 1223, Narva was a major port in the Baltic Sea during the Hanseatic League . The Grand Dukes of Moscow had always coveted this place. Ivan the Terrible managed to conquer this place during the Livonian War . It only held it for 23 years before the Swedes recaptured it. Narva was henceforth developed into a strongly secured fortress. From then on it secured eastern Estonia from access and controlled the crossing over the Narva. The fortress was secured with stone walls, had nine bastions and defensive works. The place was of great economic importance for Russia, as a considerable part of Russian trade from Pskov and Novgorod was carried out via Narva . The city's population was less than 10,000.

With the possession of this city Peter hoped the return of the Russian presence on the Baltic Sea. Nevertheless, the fortress itself was only a small section along the Baltic coast in the Gulf of Finland, which was secured by other Swedish fortresses. The fortress Nyenschantz or Nöteborg was located in neighboring Swedish Ingermanland . In Swedish Estonia, to which Narva belonged, there were still Reval or Wesenberg as significant other permanent places.

The climate was harsh and cold and the area around Narva was rather sparsely populated. The supplies therefore had to be brought in from outside, as the small population could not supply a large army. One advantage was that Russia was not far away. Narva was on the left bank of the Narva River . On the opposite bank of the river was the Ivangorod Castle , built in 1492 , which was connected to Narva by a bridge. The river made a slight curve to the east near Narva, so that the city lay in a river vault and could easily be blocked by an army on the land side from the west. Narva was only 20 miles from the Russian border and could easily be reached by an attacking army. Nevertheless, Pskov and Novgorod were more than 100 miles from Narva, so the supply routes were very stretched.

course

Main events during the campaign:

|

The campaign is divided into two parts. In the first part, the Russians took the initiative. They invaded Swedish territory and besieged Narva. They secured the western foreland by sending a cavalry division under Sheremetev. After the landing of Charles XII. In Pärnau with a small army, the Russians lost the initiative to the Swedes, who first secured the neuralgic points in the interior and then advanced with an army to Narva.

Advance to Narva

The Russian army was formally led by Fyodor Alexejewitsch Golovin as Field Marshal General . He was also Prime Minister of Peter. Peter himself formally assumed a subordinate position, but still issued the orders. During the campaign he conducted correspondence with his allies and other rulers in Europe, received embassies and represented active political agitation that was supposed to secure the legitimacy of the attack on a foreign power in the eyes of the other rulers.

Narva, not Ingermanland or Karelia , was the Russian goal, largely formed and formulated by Peter himself. The thrust was intended to lead to the conquest of the port, which in the 16th century was a “new Novgorod ” in Russian hands and for Russian trade " had been. It was therefore believed in Moscow that they had old claims to Narva, to the worry and annoyance of their own allies, who saw it as a first reach for Livonia . The Russian change of plan put Johann Reinhold von Patkul , who was instrumental in mediating the planning in the run-up to the outbreak of war between the war powers, and the Saxon Elector and King August of Poland into excitement. Patkul feared that the tsar would then claim all of Swedish Estonia and Swedish Livonia for himself and thus oppose the Polish war goal of conquering Livonia.

Russia declared war on Sweden in a manifesto in Moscow on August 19, 1700. The Swedish ambassador was arrested in Moscow. Within the next two weeks after the declaration of war, Russian troops started moving from Moscow. The two guard regiments and four other regiments were the first troop units with the artillery to leave Moscow under the command of Trubetskoi and form the vanguard. Peter accompanied the troops to Tver . There he learned on August 26th that Karl would supposedly reach Livonia with an army shortly. Despite this hoax, Peter continued the advance. He reached Novgorod four days later. Since the Swedes were not to notice anything of the advance, Peter ordered that almost all postal connections with Sweden be cut off. In Novgorod, Duke Charles Eugène de Croy , a long- serving imperial general, also entered his service as a liaison officer in the Saxon service. He brought August's request to support him with 20,000 men in the siege of Riga. Peter did not comply with this request, but assured further support after the conquest of Narva. A second important Western officer who entered Russian service there was Ludwig Nikolaus von Hallart , who received the supreme command for the technical siege work. Peter waited eight more days in Novgorod for the troops from Moscow. Autumn set in early and the rain made the roads impassable. The inadequate preparation of the campaign became apparent early on, and many regiments had already suffered losses. On September 8th, Peter continued the advance with his guard and a few other units. Two weeks later he took up siege positions in front of Narva with 10,600 men. Peter's military advance was accompanied by diplomatic work in the West; he wanted there to dispel the distrust of the Russian presence of the Russians on the Baltic Sea. Although the approach of the Russians started from Novgorod and had Narva as the main goal, the Tsar had previously occupied the Ingermanland hinterland of the city. Without meeting any resistance, he occupied the small towns south of the Neva, including the fortified towns of Koporje and Jama , which submitted without resistance. This ensured safe foraging to this side. On September 19, the advance guard of the Russian army under Prince Trubeckoj reached the heavily fortified Narva and crossed 12 kilometers above the mouth of the Narova River into the Baltic Sea; on the 20th the Tsar and his army crossed the Narova. The Tsar himself took up his quarters on an island in the Narova River. The entire Russian camp spanned the city of Narva along the Narova River and was heavily fortified. To the west, the Russian camp was secured by irregular troops, about 5,000 men, sent far into the country, mostly aristocratic troops under the command of Boris Petrovich Sheremetyev , one of Peter’s most important soldiers.

At the time of the Russian attack on Ingermanland and Estonia, Swedish troops in the region, including Livonia, were numerous by Swedish standards. In addition to the garrison that Narva was defending, there was a large Swedish detachment (up to 8,000 soldiers), which was commanded by Otto Vellingk , southeast of Pärnu ; other small departments existed in Revel and other towns including Wesenberg. When the Saxons besieged Riga in February and March 1700, Charles XII. 7000 soldiers under General Georg Johann Maydell were relocated from Finland to Livonia and another 3000 soldiers under the command of General Vellingk sailed from Narva to their destination in Livonia in April, so that at the time of the siege of Narva there were only 1500 regular troops and up to 400 armed citizens were under General Horn.

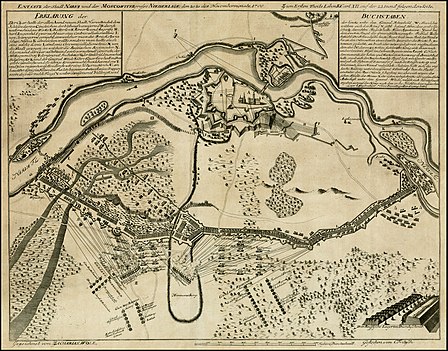

Relief of the city of NARVA and the Moscowites great defeat on 20.21. the month of November, 1700 (dated according to the Swedish calendar );

Fortifications, troop movements, batteries of the Battle of Narva drawn by Zacharias Wolf .Battle of Narva on November (20th) 30th

from: Johann Christoph Brotze : Collection of various Liefland monumentsFrench map of the Russian fortifications around Narva. The Swedish attack columns are also shown, copper engraving from 1702-1703 by Pieter Mortier .

Siege of Narva

The strength of the Russian troops has meanwhile increased to 30,000 to 35,000 soldiers due to ongoing reinforcements. Other sources speak of 40,000 men. General Avtomon Golowin commanded the northern wing on the Narva River , which was also crossed by a bridge north of the city of the same name. His brother-in-law Ivan Yuryevich Trubezkoi , governor of Novgorod since 1699 , commanded the centrally located troops, while the infantry general Adam Adamowitsch Wejde and general Boris Petrovich Sheremetev secured the south with his Cossacks. In addition, the Russian soldiers spent weeks building a kilometer-long double wall.

On October 3rd, Jul. / October 14th 1700 greg. the trenches in front of Narva were opened by the Russian army . There was an outer and an inner line. The inner, east-facing line was intended to shield the fortified Narva from the outside world, while the outer seven-kilometer line of fortifications was intended to provide additional protection against possible relief from the outside. The outer fortifications to the west were equipped with trenches and pointed wooden stakes against a possible relief army. The tents of the Russian troops stood between the lines across the wall. The arrival of the artillery was delayed due to the poor roads. The Swedish fortress commander refused any form of surrender.

The previously reinforced Swedish garrison in Narva consisted of 3,000 infantrymen, 200 cavalrymen and 400 armed civilians after further reinforcements. The Swedish Major General Peter Arvid Horn, also known as Henning Rudolf Horn, was in command . The fortress had only recently been expanded and housed large quantities of war material and supplies to withstand a long siege. Meanwhile , Russian Cossacks devastated Wierland , eastern Estonia.

It was not until October 30 that the Russians unsuccessfully bombarded the fortress with their artillery from seven different points under the command of the Russian siege artillery Alexander Imeretinsky . The transport of the guns on bad roads had been delayed. Heavy fighting ensued between November 6 and 16, in which 162 men were killed or wounded on the Russian side. The Swedish fortress artillery scored the encampment along the Russians, while the Russians themselves incapable of effective siege proved. As with the siege of Azov four years ago, the Russians lacked heavy field artillery and engineers . Most of the artillery delivered to Narva was small-caliber and did not damage the fortress walls. In addition, both Russian gunpowder and the weapons themselves turned out to be of poor quality, which greatly reduced the effectiveness of the fire. In addition, the ammunition ran out, the cannons were silent and had to wait for supplies. Overall, the artillery performed poorly: it was poorly positioned, the crews were inexperienced, the landing gear broke when the cannons were fired, and many mortars were missing bullets of the appropriate size. Despite major material damage, no more than 40 people are said to have been killed or wounded in the city as a result of the bombing .

Another piece of bad news was the lifting of the siege of Riga by the Saxons in the Russian camp. Peter feared that August would leave the alliance with him and that he would stand alone in the war against Sweden. August, on the other hand, did not trust the Russian war aims and basically remained ready for peace. A little later, the breaking off of the siege in front of Riga encouraged Charles XII to move his army not against Riga but against Narva. Peter was aware of the threatening situation and agreed to August's demands for further support in the war against Sweden in order to prevent further damage.

The conquest of the Ivangorod fortress across from Narva also failed. The two regiments charged with it were repulsed with heavy losses.

Landing of Charles in Estonia

After the early Peace of Traventhal , in which Denmark withdrew from the three-party alliance against Sweden at an early stage, the Swedish King Charles XII spent the next two months in Skåne to prepare for the next campaign. In response to the Saxon incursions into Livonia and the siege of Narva by Russian troops , it was under the command of Charles XII. A small Swedish relief army of a few thousand men was raised in Sweden , shipped in nine warships in Karlskrona and landed at Pernau in the Baltic on October 6th, 17th. Due to the autumn storms on the Baltic Sea, there were sick leave during the crossing. The Swedes stayed at Ryen for five weeks to rally the army and pull in further reinforcements. Initially it was planned to relieve Riga, but Karl decided, against the advice of all his generals, to march north with the Swedish army towards Narva to lift the blockade . Otto Vellingk's troops were in Ryen after he had withdrawn from Riga. He received the order to position himself with his troops at Wesenberg and to set up and cover a supply base. The units of Oberste Schlippenbach and Skytte were sent to Dorpat to observe the movements of the Russians and Saxons there. In the meantime, King Karl went to Reval with the remaining troops.

Skirmishes in Estonia

The Vellingk department was in Wesenberg with the task of securing the last outpost before Reval, the capital of Estonia. In the weeks from the end of October to the end of November, the latter had contact with the enemy on several occasions with the Russian vanguard of Sheremetev, during which there were skirmishes . On October 25th, Jul. / 5th November 1700 greg. A 20-man vanguard division under Vellingk attacked the approximately 200-man Russian cover in Purtse . The Swedes took advantage of the carelessness of the Russian soldiers standing in Purtz and won an easy victory. One day later, on the evening of October 26th, July. / November 6th 1700 greg. , the advance commandos of the Swedes attacked 3000 Russian soldiers in the village of Varja with about 600 horsemen . Russian soldiers had settled in the houses of the village without posting guards and were easy prey for the small Swedish detachment. Suddenly the Swedes went into the village, set it on fire and were given the opportunity to intercept the Russians who had caught them by accident. Several Russian cavalrymen managed to escape to Povanda and to inform Sheremetev of what had happened. Sheremetev immediately sent a large division consisting of 21 cavalry squadrons, which surrounded the Swedes at Varja. The Swedes withdrew from the encirclement with combat and losses, but two Swedish officers were captured. These two officers, following the instructions of Charles XII. followed misrepresented the strength of the Swedish army advancing on Narva by repeatedly inflating the number of 30,000 and 50,000 Swedish soldiers.

Despite the success achieved, Sheremetev decided not to hold the position in Purtse, but withdrew 30-50 kilometers east to the village of Pühajõgi . Sheremetev was concerned about the unexpected attacks by the Swedes and saw the slowness of his cavalry in the swamp. He recognized the danger that the Swedes could bypass his line-up and cut them off from the main Russian forces. Peter ordered Sheremetev to hold the position at Pühajõgi.

Despite the inferiority of the Swedes, Charles XII. returned significant troops at other locations to protect Estonia. This precaution necessitated the strategic containment of Russian troops. 10,000 Russians under Repnin were in Novgorod and another 11,000 Cossacks were under Obidovskogo command. Guided by these considerations, Charles XII. several thousand regular soldiers and militiamen in Reval and sent a 1,000-man detachment under the command of the officer and commander of the Swedish troops in Livonia Wolmar Anton von Schlippenbach to Pskow , Karl feared that a Russian offensive could be undertaken from there to Dorpat . On October 26th (November 6th) Schlippenbach defended Räpina with his 600-strong cavalry detachment on the west bank of Lake Peipus, 46 kilometers southeast of Dorpat, against the approximately 1500-strong militia officers from Pskov. The Russian department is said to have taken no precautionary measures and was surprised by the attack by the Swedes. The Russians are said to have suffered 800 losses and 150 prisoners. Schlippenbach also captured a dozen Russian ships and the banner of the Pskov province.

Swedes advance to Narva

When Charles XII. received news about the consequences of the clashes at Purtse, he decided to move with a relatively small detachment of 4,000-5,000 soldiers from Reval to Wesenberg, where he joined General Vellingk's department. The other troops stayed behind in Reval. As soon as he arrived in Wesenberg, the Swedish king decided, against the advice of some of his generals, to advance to Narva. Charles XII. commanded an army with a total strength of 10,537 men when marching out of Wesenberg. In order to keep the marching speed as high as possible, the soldiers were not allowed to carry any supplies with them that went beyond the minimum required. For a week the path led through devastated land with bad roads and three passes to be overcome. Everywhere one saw only burned-out farmhouses and villages. Nowhere was there any food for the horses or food for the soldiers. The cold November rain soaked the soldiers to the skin and they suffered from hunger. At night the rain turned to snow, the ground began to freeze, and the soldiers, like the king, had to sleep on the muddy ground.

The passes were critical points and could have turned into a dangerous trap with a more active opponent than the Russians off Narva. Fortunately for the Swedes, the first two passes were unguarded, but 30 km before Narva there was a small skirmish at the Pyhäjöggi gorge between the 800-strong Swedish vanguard under Charles XII. and Major General Georg Johann Maydell and the 5,000-strong Russian vanguard under General Sheremetev . The Russian vanguard immediately withdrew from the pass after the Swedes prepared for a serious attack. On November 29th, the soaked and muddy Swedes, led by an Estonian farmer over narrow forest paths and muddy ground, reached the burned down La Gena manor, a mile and a half outside Narva. There they sent a signal with two rockets to the enclosed fortress, which responded in the same way and thus indicated to the army that they were still holding the fortress. The Swedish troops were emaciated by the advance and were hungry and were therefore hardly in a condition fit for combat. Nevertheless, the King Charles XII. his troops to battle.

Unrest in the Russian camp

Before Narva, the Russian army was in a tense situation. The Swedes continued to make failures, the containment of which cost the Russians heavy losses. There was still no ammunition for the siege artillery. In the Russian camp there were rumors that Charles XII. could show up every day. The morale of the Russians was at a low point.

Since Sheremetev's detachment did not conduct a reconnaissance and had never conducted an organized battle with the Swedish main detachment, the Russians did not have reliable information about the strength of the Swedish army, but there were false testimony by Swedish prisoners about 50,000 Swedes allegedly approaching Narva. After Sheremetev had arrived at the Russian camp with news of the battle at the Pyhäjöggi Gorge on November 27, Peter, Fyodor Alexejewitsch Golovin and Alexander Danilowitsch Menshikov had rushed, if not to say in flight, left the camp. Peter had expected that the Danish and Polish-Saxon forces would tie up a large part of the Swedish army. But now Denmark had already been forced to peace and Karl advanced with a Swedish army where the Russians weren't even expecting him. Based on the reports from Sheremetev, Peter believed that Karl's army numbered around 30-32,000 men, so it was much larger than it actually was. The Tsar found himself unable to withstand the Russian army, which was mainly made up of recruits, against the main Swedish army, which was considered to be the best army at the time. Another possible explanation for Peter’s sudden disappearance was that he had already recognized the day before the battle as inevitable and left it before the battle to be on the spot in Moscow. The main thing was to absorb the loss of political and diplomatic prestige caused by this first defeat.

Charles Eugène de Croÿ took his place in command of the Russian army in front of Narva. This decision turned out to be momentous: Croÿ did not speak Russian, did not know the Russian officers under his command and therefore had difficulties giving orders. In addition, he did not agree to the formation of Russian troops. The Russian siege positions were drawn too far apart and prevented a dense staggered formation. The lines were therefore sparsely manned when the Swedish army arrived and could not withstand a massive attack. After the Swedish army arrived at Narva, the Russian camp sounded the alarm. Croy held a council of war with his generals and gave orders to set up additional night watches. The joint war council decided to remain in the fortified position and against an open field battle, since they saw the Russian recruits not in a position to withstand a battle-tested army in the field.

Battle of Narva begins

Knowing that the center of the Russian army was most fortified, the king decided to concentrate the Swedish attacks on the flanks, pushing the Russians to the fortress and throwing them into the river. The king personally commanded the army from the left wing at the head of his livguard . There were a total of 21 infantry battalions, 47 squadrons, 21 regimental cannons and 16 field guns in the Swedish army. In the middle on the Hermannensberg the Swedish artillery stood under the command of Generalfeldzeugmeister Baron Johann Schöblad. The right flank was commanded by Carl Gustaf Rehnskiöld (three columns of 10 battalions), the left by Otto Vellingk (11 battalions of infantry and 24 squadrons of cavalry). In front of the columns were 500 grenadiers with fascines .

A heavy snowstorm initially seemed to paralyze the movements of both armies. But around noon the wind turned and blew the Russians in the face. Karl, realizing the deficiencies in the Russian line-up, ordered the attack, which his guns could effectively support. The Swedish salvos inflicted heavy losses on the Russian troops, while they were neglected because of the headwind and lack of ammunition. After a quarter of an hour there was already great disorder in the Russian position. Instead of advancing the attack along the entire line, a massive center of gravity attack should be made. The attack began at two in the afternoon. The blizzard continued to blow the Russians in the face and obstructed their view. The first blow was delivered with two deep wedges. The Russian troops stood in a line almost six kilometers long and, despite the numerical superiority, the line of defense was very weak. The breakthrough took place in half an hour. Swedish grenadiers threw fascines into the trenches and climbed the wall. Thanks to the speed of the onslaught and the coherence of the attack, the Swedes broke into the Russian camp. Fierce hand-to-hand fights with swords took place within the lines. Eventually the Swedes managed to split the Russian line into three parts. The Swedes invaded the interior of the Russian camp and rolled up the Russian right flank against the Narva River. Panic began to spread in the Russian regiments. As the disorder spread, Russian soldiers began shooting their foreign officers.

Only a small core of troops held out, the two guards and two line regiments defended a wagon castle and fought until dusk, thus preventing a slaughter of Russian troops. The Swedish offensive stalled and the inexperienced Russian recruits stopped panicking and joined the experienced regiments. Several times, Charles XII. personally attacked the Swedes, but each time he had to withdraw. For those fleeing, however, the northern bridge over the Narva became a death trap. When the bridge over the Narva collapsed under the weight of those fleeing, disaster struck. Thousands drowned in the icy river, many were killed. Sheremetev's cavalry withdrew to Syrensk on the left bank of Narva, where they crossed the southern bridge over the Neva and went to Pskov. The Commander-in-Chief Duke von Croy and a number of foreign officers (including Lieutenant General Ludwig Nikolaus von Hallart , the Saxon envoy Langen, the Colonel of the Preobrazhensky Regiment Bloomberg) surrendered to the Swedes after the fall of the center and the right wing. On the left flank of the Russians, however, the soldiers of Adam Adamowitsch Weide's division stood and were the only ones to repel all attacks by the Swedes. Swedish Major General Johan Ribbing died in the battle . The fight ended with the onset of darkness at five o'clock in the afternoon.

Russian troops surrender

The night worsened the disorder in the Russian and Swedish units. Part of the Swedish infantry that had penetrated the Russian camp attacked the Russian entourage and got drunk from the stocks of brandy. Two Swedish battalions mistook each other for Russians in the dark and fought against each other. Some of the Russian troops on the left wing below Weide maintained order, but suffered from a lack of leadership. There was no connection between the right and left Russian flanks. The next morning the remaining Russian leadership decided to start negotiations for the handover. Prince Vasily Vladimirovich Dolgorukov agreed to the free withdrawal of troops with weapons and flags, but without artillery and baggage train. The remaining division from Weide surrendered only on the morning of December 2nd on condition of free withdrawal without arms and flags. The conditions of the handover also included that 700 people should be transferred to Sweden, 10 of them were generals, 10 colonels, 6 lieutenant colonels, 7 majors, 14 captains, seven lieutenants, 4 other officers, 4 sergeants, 9 fireworks masters and bombarders and other.

The shortcomings of the Russian army were evident in the debacle off Narva. There was only one experienced regiment, that of François Le Fort . The two guard regiments, the Preobrazhensky bodyguard regiment and the Semyonovskoye bodyguard regiment , had participated in two attacks on the city of Narva, but had never been involved in an open field battle or fought against a regular army. In the other regiments, with the exception of a few colonels ( regiment owners ), officers and men had been inexperienced. Russian distrust of foreigners in their army - a large proportion of whom were commanding officers - became evident after the battle, when survivors blamed their foreign officers for their poor performance. Some were murdered while the army commander at Narva, Duke du Croy, escaped this only through his imprisonment.

The Swedish casualties amounted to 676 dead out of 1,247 wounded. The data on the Russian losses vary, but they were very considerable and significantly higher than those of the Swedish. Of the captured Russians, only the officers were transferred to Sweden, while the men were released again. The victorious Swedish troops were too exhausted for further operations and then went to winter quarters. In the spring they continued the campaign and defeated the Saxons in the battle of the Daugava .

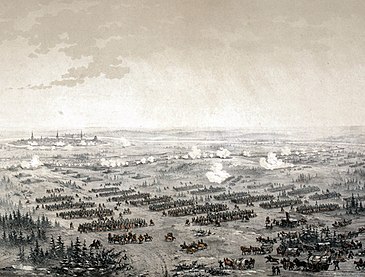

Alexander von Kotzebue : Battle of Narva

Gustaf Cederström (1912): The Victory of Narva

consequences

The military defeat of the Russian army at Narva was complete. The campaign goal, the conquest of the city, could not be achieved. In addition, considerable military losses had been suffered. A large number of standards , prestigious symbols of the Russian military units passed into Swedish possession as a sign of defeat. About 160 cannons and mortars were captured by the Swedes. The Czar's war chest also fell into the hands of the Swedes. The number of convicted prisoners of war, including 20 high-ranking generals and colonels, was considerable. Despite their high rank, they suffered severe conditions while they were prisoners of war in Sweden. The train with provisions and other military supplies was also lost to the Swedes. The Swedish king entered the city victoriously after the battle of Narva.

On the question of further action against the Russians were in the war council of Charles XII. different opinions expressed. The majority spoke out in favor of turning south-west in order to drive August's army out of Riga. The fact that Polish forces could stab him in the back as soon as he dared to invade Russia spoke against a direct move to Moscow. Both the supply situation and the supply of additional troops were rated as critical for a train to Russia in contrast to Poland, which promised far better conditions for an army campaign. Karl believed that he would have beaten the Russians for years. He thought he knew enough about the combat value of the Russian troops.

In any case, the Swedish forces were too exhausted to pursue the defeated Russian troops in the winter. After storming the Russian camp, the Swedes plundered the provisions and brandy stocks. Many Swedes were drunk or overeating and suffered from stomach cramps. So the Russian troops were able to gather again in front of Novgorod and withdraw further, at least around 23,000 men who could be combined again into operational units in a few weeks. The Swedish troops did not leave for Riga until the spring of 1701.

This gave Peter the break in the fight that he so urgently needed in order to organize his troops and to raise the fighting spirit of the Russian troops. Up until then, the tsar's situation was extremely critical. He feared another offensive by the Swedes against Novgorod and Pskow , where he hastily had fortifications raised. Civilians were also mobilized to carry out this work. However, the Russian military setback was only effective for a short time. Peter himself drew the necessary conclusions from his first serious military defeat. He turned to the overdue army reform, armaments and the reorganization of the state administration. He recruited new recruits from all classes of the population. In churches all over the country, he had some of the bells confiscated so that cannons could be poured out of them, as the guns captured by the Swedes had to be replaced. A year later the army went on the offensive again in Livonia .

Evaluation of the tactics of both armies

The Swedish army under Charles XII. followed a strict offensive doctrine which was supposed to have a shock effect on the enemy and undermine the cohesion of the opposing associations. As such, the actions of the Swedes before Narva became a model for the struggles of the next few decades. With a silent march through difficult terrain, the Swedes secured the element of surprise. Without stopping and then opening fire, their cavalry attacked immediately. The artillery was also faster than the Russian artillery. As a result, the defenders could not keep the attackers at bay and the Russian lines collapsed.

The Russian federations acted statically and timidly and were too afraid of the Swedes. The great fear of the common soldiers was based on their inexperience and inexperience with the craft of war. As an association, they could only defend in firmly established positions. The relationship between officer and soldier level was particularly strained due to the officers' frequent foreign origins, as evidenced by the shootings of officers by their own teams. They were accused of treason by their own soldiers.

Reception and reminder

In June 1700, journalistic Europe was already informed about the Russian troop movements along the border with Sweden and the ban on trading with Narva. Peter I, however, denied any war intentions. It was even announced that an embassy would be sent to Stockholm. The conquest of the Narva fortress was ultimately hyped up as a question of prestige in the newspapers. The event surrounding the successful relief of the hard-pressed Narva fortress by the young Swedish King Charles XII. was widely noticed and described in the media of the time across Europe. After weeks of reports of victories, lists of casualties and prisoners, captured weapons and artillery, and descriptions of the celebrations that took place in Sweden itself and by the diplomatic representatives of Charles XII. were celebrated at European courts, printed. Numerous commemorative medals were minted. In the eyes of the Western European readers of the time, the Russian forces were weak and inferior to the Swedish forces, even if they were numerically superior. The loss of prestige for the Russian side weighed heavily. This did not change until 1709 after the Battle of Poltava , with the victory the Russian army was able to settle its debacle of 1700 in the eyes of European opinion leaders.

To this day, the battle of Narva is part of the collective European historical memory as part of the entire campaign. Numerous memorabilia that were captured from the Russian camp in the course of the battle document the events of that time and are illustrated in museums, for example in Stockholm.

Medal with the portrait of Charles XII. of Sweden and view of the Battle of Narva in 1700

Scan from Johann Christoph Brotze 's book Collection of various Liefländischer monuments . "The relief of Narva in 1700 [the plan]."

Monuments

Monument to Russian soldiers on the Victoria bastion

In 1900, on the initiative of the Life Guards, a memorial to the fallen Russian soldiers was erected near the village of Vepskyul on the 200th anniversary of the first Battle of Narva . The monument is a granite rock with a cross, mounted on a cut-off earth pyramid. The inscription on the memorial reads: “Heroes-ancestors who died in battle 19 N0 1700. L.-G. Preobrazhensky, L.-G. Semenovskiy regiments, 1st battery, l. 1st artillery brigade. November 19, 1900 "

Swedish lion

The first Swedish memorial to the battle was opened in Narva in 1936 and disappeared without a trace after the Second World War. The new one was opened in October 2000 by the Swedish Foreign Minister Lena Elm-Vallen . In the granite is embossed: "MDCC" (1700) and "Svecia Memor" (Sweden remembers).

See also

Web links

- Welt-Online: Sweden-Russia-Army destroyed in a snowstorm , published on November 30, 2017

literature

- Gustavus Adlerfeld , Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding : The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740

- Erik Amburger : Ingermanland. A young province of Russia within the sphere of influence of the residence and cosmopolitan city of St. Petersburg - Leningrad. Böhlau, Vienna 1980, p. 43

- Astrid Blome : The German image of Russia in the early 18th century: Investigations into contemporary press coverage of Russia under Peter I. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2000, Chapter 2: The Northern War (p. 92–182)

- Robert I Frost: The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721 Longman. 2000, ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4 , pp. 230, 232.

- Peter Hoffmann : Peter the Great as a military reformer and general. Chapter: The "great luck" of the defeat at Narva. (Pp. 55–67), Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010

- Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980

- Lothar Rühl : Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire - The Path of a Millennial State, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1992, Chapter 7: The empire of Peter the Great and Russia's claim to European power (pp. 156–187)

- Klaus Zernack : Northeast Europe. Sketches and contributions to a history of the Baltic countries. Verlag Nordostdeutsches Kulturwerk, 1993, p. 171.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g Jeremy Black: Warfare. Renaissance to revolution, 1492–1792. Cambridge Illustrated Atlases. 2. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-47033-1 , p. 111.

- ↑ Jeremy Black: The Wars of the 18th Century, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1999, p. 163, 166f

- ↑ Valentin Gitermann: History of Russia, Volume Two, Gutenberg Book Guild, Frankfurt am Main, Vienna, Zurich, 1965, p. 78f

- ↑ Valentin Gitermann: History of Russia, Volume Two, Gutenberg Book Guild, Frankfurt am Main, Vienna, Zurich, 1965, p. 80

- ↑ Valentin Gitermann: History of Russia, Volume Two, Gutenberg Book Guild, Frankfurt am Main, Vienna, Zurich, 1965, p. 81

- ↑ Hans Joachim Torke (ed.): The Russian Tsars 1547-1917. Beck, Munich 1999, chapter: Peter (I.) der Große by Erich Donnert (p. 155–178), p. 62.

- ↑ Lothar Rühl : Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire - The Path of a Millennial State, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1992, Chapter 7: The Empire of Peter the Great and Russia's European Claim to Power (p. 156–187), p. 175

- ^ Angus Konstam : The Army of Peter the Great, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus , 2010, ISBN 978-3-941557-31-4 , p. 15; German translation of the English original edition: Peter the Great's Army, Osprey Publishing Ltd, Midland House 1993

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 324

- ^ Angus Konstam : The Army of Peter the Great, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus , 2010, ISBN 978-3-941557-31-4 , p. 68; German translation of the English original edition: Peter the Great's Army, Osprey Publishing Ltd, Midland House 1993

- ^ Henry Vallotton: Peter the Great - Russia's Rise to a Great Power. Munich 1996, p. 165.

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 324

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 323

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 324

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 323

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 323

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 324

- ↑ Петров А. Нарвская операция // Военный сборник. - Санкт-Петербург: Изд. Военного министерства Российской империи, 1872. - № 7. - С. 5-38.

- ^ Robert I Frost: The Northern Wars. War, State and Society in Northeastern Europe 1558-1721 Longman, 2000, ISBN 978-0-582-06429-4 , pp. 230, 232.

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 324

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 324

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 324

- ↑ Lothar Rühl : Rise and Fall of the Russian Empire - The Path of a Millennial State, Deutsche Verlagsanstalt, Stuttgart 1992, Chapter 7: The Empire of Peter the Great and Russia's European Claim to Power (p. 156–187), p. 175

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 325

- ^ Kurtze Relation of a King who was in Narva. Servants, concerning their, siege, 1701 , p. 5

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 325

- ^ The Cambridge Modern History , Volume Five, Cambridge, At the University Press, 1908, p. 588

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 45

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 46

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 46

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 47

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 45

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 48

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 326

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 49

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 49

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 329

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 329

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 330

- ↑ Карл XII и шведская армия. Путь от Копенгагена до Переволочной. 1700-1709. - М .: Рейтар, 1998, ISBN 5-8067-0002-X , p. 43.

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 50

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 332

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, pp. 53f

- ^ Robert K. Massie: Peter the Great: His Life and World, Random House Trade Paperbacks, New York, 1980, p. 333

- ^ Angus Konstam : The Army of Peter the Great, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus , 2010, ISBN 978-3-941557-31-4 , p. 44; German translation of the English original edition: Peter the Great's Army, Osprey Publishing Ltd, Midland House 1993 .

- ^ Gustavus Adlerfeld, Carl Maximilian Emanuel Adlerfelt, Henry Fielding: The Military History of Charles XII, King of Sweden, Volume 1, London 1740, p. 55

- ^ Angus Konstam : The Army of Peter the Great, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus , 2010, ISBN 978-3-941557-31-4 , p. 16; German translation of the English original edition: Peter the Great's Army, Osprey Publishing Ltd, Midland House 1993

- ↑ Jeremy Black: The Wars of the 18th Century, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1999, p. 171

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann: Peter the Great as a military reformer and general. Chapter: The "great luck" of the defeat at Narva. (Pp. 55–67), Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 62.

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann: Peter the Great as a military reformer and general, chapter: The "great luck" of the defeat at Narva (p. 55-67), Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 61

- ↑ Peter Hoffmann: Peter the Great as a military reformer and general, chapter: The "great luck" of the defeat at Narva (p. 55-67), Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2010, p. 63.

- ↑ Jeremy Black: The Wars of the 18th Century, Brandenburgisches Verlagshaus, Berlin 1999, p. 177

- ↑ Astrid Blome : The German image of Russia in the early 18th century: Investigations into contemporary press coverage of Russia under Peter I, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2000, Chapter 2: The Northern War (p. 92–182), p. 98

- ↑ Astrid Blome : The German image of Russia in the early 18th century: Investigations into contemporary press coverage of Russia under Peter I, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden, 2000, Chapter 2: The Northern War (p. 92–182), p. 96