Invasion of Sweden in 1674/75

|

Chronology: 1674

1675

|

The Swedish incursion 1674/75 describes the occupation of the militarily unsecured Mark Brandenburg by a Swedish army coming from Swedish Pomerania from December 26, 1674 to the end of June 1675. The Swedish incursion triggered the Swedish-Brandenburg War , which was followed by further declarations of war Brandenburg allied European powers spread to a Northern European conflict and was not ended until 1679.

The trigger for the invasion of Sweden was the participation of a 20,000-strong Brandenburg army in the Imperial War against France as part of the Dutch War . Thereupon Sweden , a traditional ally of France, occupied the militarily unsecured mark with the declared aim of forcing the Brandenburg elector to make peace with France. It was not until the beginning of June 1675 that the elector set out from Schweinfurt with an army of 15,000 and reached Magdeburg on June 11th . / June 21, 1675 greg. In a campaign of less than ten days, Friedrich Wilhelm forced the Swedish troops to withdraw from the Mark Brandenburg.

prehistory

Louis XIV , King of France, pressed for retribution against the States General after the War of Devolution . He began diplomatic activities with the aim of isolating Holland completely. On April 24, 1672, France concluded a secret treaty with Sweden in Stockholm, which obliged the Nordic power to deploy 16,000 men against every German state that provided military support to the Republic of Holland.

Immediately afterwards, in June 1672, Louis XIV attacked the States General, thus triggering the Dutch War and advancing until shortly before Amsterdam . The Elector of Brandenburg supported the Dutch, contractually bound, in their fight against the French from August 1672 with 20,000 men. In December 1673, Brandenburg-Prussia and Sweden signed a ten-year protective alliance. However, both sides reserved a free choice of alliance in the event of war. Due to the protective alliance with Sweden, the elector did not expect Sweden to enter the war on the side of France in the subsequent period. After the separate peace at Vossem between Brandenburg and France on June 16, 1673, Brandenburg resumed the war against France the following year, when the Holy Roman Emperor declared the Imperial War against France in May 1674.

On August 23, 1674, a 20,000-strong Brandenburg army marched from the Mark Brandenburg to Strasbourg . Elector Friedrich Wilhelm and Elector Prince Karl Emil von Brandenburg accompanied this army. Johann Georg II von Anhalt-Dessau was appointed governor of the Mark Brandenburg .

Through promises of subsidies and bribes, France has meanwhile succeeded in persuading its traditional allies Sweden, which had only been saved from the loss of all of Western Pomerania in the Peace of Oliva in 1660 with French support , to enter war against Brandenburg. The main reason was the concern of the Swedish court that if France were to lose, Sweden could become isolated in foreign policy. The aim of the Swedish entry into the war was to occupy the militarily bared Mark Brandenburg in order to force Brandenburg-Prussia to withdraw its troops from the theaters of war on the Upper Rhine and Alsace .

War preparations

Painting by Matthäus Merian the Younger, 1662

The Swedes then began to assemble an invading force in Swedish Pomerania . From September onwards, more and more news of these troop movements reached Berlin. At the beginning of September the governor of the Mark Brandenburg reported to the elector about a conversation with the Swedish ambassador Wangelin , in which he had announced that before a month there would be over 20,000 Swedish troops in Pomerania. The news of an imminent attack by the Swedish troops intensified when the arrival of the Swedish general Carl Gustav Wrangel in Wolgast was announced in the second half of October .

At the end of October, Johann Georg II von Anhalt-Dessau, clearly alarmed by news about the troop rallies, asked the Swedish Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel about the intention of the march several times via the Brandenburg Colonel Mikrander . Wrangel, however, failed to respond and declined a further request to speak from the Prince of Anhalt. In mid-November the governor Johann Georg II had received certainty about an imminent Swedish invasion, but in Berlin the exact causes and motives for the impending aggression remained unclear.

Elector Friedrich Wilhelm himself, in spite of the disturbing news coming from Berlin, did not believe in an imminent Swedish invasion of the Mark Brandenburg. This is evidenced by a letter he wrote to the governor of the Mark Brandenburg dated October 31, 1674, which among other things said:

"I trust the Swedes to do better and do not believe that they will let [wickedness] do anything."

"Wihr peasants of low quality serve our noble electors and lords with our blood"

According to contemporary information from the Theatrum Europaeum, the strength of the Swedish invasion army gathered in Swedish Pomerania before the invasion of the Uckermark at the end of December 1674 was as follows:

- The infantry consisted of eleven regiments with a total of 7,620 men.

- The cavalry consisted of eight regiments, a total of 6,080 men.

- The artillery had a total of 15 guns of various calibers.

The state of defense of the Mark Brandenburg was inadequate after the withdrawal of the main army on 23 August 1674 to Alsace. The elector had only a few soldiers, mostly elderly and disabled men. These little combat units were left behind as a garrison in the fortresses. The total strength of the garrison troops available to the governor was only around 3,000 at the end of August 1674. At that time there were 500 older soldiers left behind due to their reduced fitness for war and 300 newly recruited soldiers in the capital Berlin. New recruits from soldiers therefore had to be accelerated immediately. The elector also ordered the governor to call in the general contingent of the rural people and the cities in order to compensate for the lack of operational troops. The so-called Landvolkaufgebot was based on medieval legal norms of the Mark Brandenburg, according to which farmers and towns could be used for direct national defense if necessary. Only in lengthy negotiations between the estates and cities on the one hand and the Privy Councilors and the governor on the other hand was it possible to enforce the list at the end of December 1674. Most of this contingent was deployed in the royal cities of Cölln , Berlin and Friedrichswerder (8 companies with 1,300 men). It was also possible to mobilize the Altmark farmers and Heidereiter (forest staff with knowledge of the country) and use them for defense. The governor received further reinforcements at the end of January 1675 by sending troops from the Westphalian provinces.

course

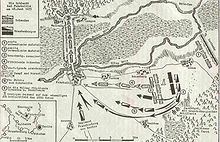

Invasion of Sweden - Occupation of the Mark (December 25, 1674 – April 1675)

Swedish-Pomerania is shown with gray hatching.

On 15./25. December 1674, Swedish troops entered the Uckermark via Pasewalk without an official declaration of war . Actually, according to a communication from the Swedish Field Marshal Wrangel to the Brandenburg envoy Dubislav von Hagen on 20./30. December 1674 the Swedish army left the Mark Brandenburg again as soon as Brandenburg ended the state of war with France. A complete break between Sweden and Brandenburg, however, was not intended.

The information on the initial strength of this army, which next spring should consist of almost half of Germans, varies in the literature between 13,700 and 16,000 men and 30 guns.

Field marshals Simon Grundel-Helmfelt and Otto Wilhelm von Königsmarck were given to support Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, who was already over 60 years old and often bedridden and suffered from gout . However, this unclear allocation of competencies prevented clear orders from being issued, so that decisions for the movements of the army were taken very slowly.

Sweden's entry into the war attracted general attention in Europe. The war fame of the Thirty Years' War made Sweden's military power appear overwhelming in the eyes of contemporaries. German mercenaries willingly offered their services to the Swedes. Some German states (Bavaria, the Electorate of Saxony , Hanover, the Diocese of Munster ) agreed to join the Swedish-French alliance.

The Swedish army set up their headquarters in Prenzlau . Another division under General Dalwig , armed in Bremen-Verden, Sweden, was added.

At the same time, after the imperial Brandenburg defeat in the battle of Türkheim against the French on December 26, 1674, the main Brandenburg army moved into winter quarters in and around Schweinfurt , which it reached on January 31, 1675. Due to the losses suffered and the wintry weather, the elector decided that he could not immediately lead his main army to another campaign in the Uckermark. In addition, a sudden withdrawal from the western theater of war would have put the allies of Brandenburg-Prussia in distress - with which the actual aim of the Swedish attack, namely to force Brandenburg to withdraw from the war with France, would have been achieved.

Without further reinforcements, the open areas of the Neumark east of the Oder and Hinterpommern on the Brandenburg side could not be held, apart from a few fortified places. The Mittelmark , on the other hand, could be maintained with relatively few troops, because to the north, due to the Havelländische Luch and the Rhinluch , it could only be passed over a few easy-to-defend passes at Oranienburg , Kremmen , Fehrbellin and Friesack . In the east the mark was covered by the river Oder. The few existing Brandenburg soldiers were then withdrawn to fortified places. The Brandenburg defensive positions on the line Koepenick , Berlin, Spandau , Oranienburg, Kremmen, Fehrbellin, Havelberg and the Elbe developed from the given circumstances . For this purpose, among other things, the garrison of the fortress Spandau was reinforced from 250 to 800 men, it had 24 guns of different calibers. In Berlin, the garrison was increased to 5000 men (including the reinforcements from the Westphalian provinces at the end of January and the Leibdragoner regiment sent by the Elector from Franconia ).

The Swedes remained inactive and failed to take advantage of the absence of the Brandenburg Army and occupy the vast areas of the Mark Brandenburg. At first they limited themselves - while consistently maintaining discipline - to the raising of war contributions and the reinforcement of the army by recruiting mercenaries to 20,000 men. This inaction was due in part to the internal political clashes between the old and new Swedish governments, which prevented targeted military warfare. Resolutions thus came into conflict with one another; an order was soon followed by a counter-order.

At the end of January 1675, Wrangel gathered his troops near Prenzlau and on February 4th crossed the Oder with the main force in the direction of Pomerania and Neumark . Swedish troops occupied the places Stargard , Landsberg , Neustettin , Kossen and Züllichau in order to have advertising carried out there too. Western Pomerania was occupied except for Lauenburg and a few smaller towns. Then Carl Gustav Wrangel released the Swedish army to winter quarters in Pomerania and Neumark.

When it became clear in early spring that Brandenburg-Prussia would not leave the war, the Swedish court in Stockholm ordered the use of a stricter occupation regime to increase the pressure on the elector to exit the war. The Swedes' policy of occupation changed rapidly, with the result that the repression against the land and the civilian population rose sharply. Some contemporary chronicles describe that these excesses were worse in their dimensions and brutality than in the time of the Thirty Years' War . Up until the spring of 1675, however, there were no significant fighting. The governor of the Mark Brandenburg Johann Georg II. Von Anhalt-Dessau described this limbo in a letter to the elector on March 24th / 3rd. April 1675 with:

"Neither peace nor war"

Swedish Spring Campaign (early May 1675–25 June 1675)

The French envoy in Stockholm demanded on 20./30. March that the Swedish army should expand its quarters to Silesia and act in accordance with the French plans. However, the French side changed their stance in the weeks that followed, leaving the Swedish side room to make decisions on this matter. However, the envoy in Stockholm expressed concern over the alleged inaction of the Swedish troops.

At the beginning of May 1675, the Swedes began the spring campaign, which they had expressly called for. The goal was to cross the Elbe in order to unite with the Swedish troops in Bremen-Verden and with the 13,000-strong troops of the allied Johann Friedrich Duke of Braunschweig and Lüneburg , in order to give the Elector and his army the route to the Kurmark to cut off. A force that had meanwhile grown to 20,000 men and 64 artillery pieces then moved via Stettin to the Uckermark. Although the state of the Swedish army was no longer comparable to past times, the former reputation of Sweden's military power was retained. Not least, this led to quick initial success. The first fighting took place in the area of Löcknitz , where on 5./15. May 1675 the fortified castle with a 180-man crew under the command of Colonel Götz was handed over to Oderburg after a day's bombardment by the Swedish army under the command of Sergeant Jobst Sigismund against the assurance of free departure . For this, Götz was later sentenced to death by a court martial and executed on March 24, 1676.

After the capture of Löcknitz, the Swedes quickly advanced south and occupied Neustadt , Wriezen and Bernau . The next destination was the Rhinluch , a moorland that could only be crossed in a few places. As a precaution, these were occupied by the Brandenburgers with country hunters, armed farmers and heather riders. The governor sent troops and six guns from Berlin under the command of Major General von Sommerfeld to provide support at the passes of Oranienburg, Kremmen and Fehrbellin.

The Swedes advanced in three columns against the Rhinlinie, the first under General Stahl against Oranienburg, the second under General Dalwig against Kremmen and the third - the strongest with 2000 men - under General Groothausen against Fehrbellin. Before Fehrbellin there was heavy fighting for several days over the river crossing. Since the Swedes failed to make a breakthrough here, the column turned in the direction of Oranienburg, near which, through betrayal by local farmers, a crossing was found that enabled the approximately 2000 Swedes to advance south. The bypassed positions of Kremmen, Oranienburg and Fehrbellin had to be given up by the Brandenburgers.

Shortly afterwards, the Swedes launched an unsuccessful assault on the Spandau fortress. The whole of Havelland was occupied by the Swedes, and the Swedes' headquarters were initially set up in the city of Brandenburg . After the capture of Havelberg was on 8./18. June the Swedish headquarters moved to Rheinsberg .

Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, who set out from Stettin on May 26th / June 6th to follow the army, only got as far as Neubrandenburg because a severe attack of gout tied him to bed for 10 days. The highest order now passed to Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel . In addition, there was disagreement between the generals, so that the general discipline of the soldiers dissolved and serious looting and attacks against the civilian population began. So that the troops could get the necessary supply of food, they were relocated to widely spaced quarters. Because of this interruption, the Swedes lost two valuable weeks for the crossing over the Elbe.

Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel finally arrived sick and carried on a sedan chair on 9/19. June Neuruppin . He immediately forbade all looting and ordered that reconnaissance teams be sent in the direction of Magdeburg. On 11/21 June he set out for Havelberg with one regiment of infantry and two cavalry regiments (1500 riders) . reached to occupy the Altmark in the coming summer . So he had all available vehicles brought together on the Havel in order to build a ship bridge over the Elbe.

At the same time he gave orders to his stepbrother Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel to join him in Havelberg with the main army over the bridge at Rathenow . Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel , commander-in-chief of the main armed forces, under whose command around 12,000 men were, was at that time in the city of Brandenburg an der Havel. The line connecting Havelberg and Brandenburg an der Havel was only maintained by one regiment in Rathenow. This wing, secured only with little strength, offered a good point of attack for an enemy advancing from the west. At this point in time, June 21, a large part of the Mark Brandenburg was in Swedish hands. The crossing of the Swedes over the Elbe near Havelberg, planned for June 27, never came to fruition.

In the meantime, the Brandenburg Elector Friedrich Wilhelm tried to win allies, knowing full well that his country's forces were insufficient for a campaign against the military power of Sweden. To this end, he went to The Hague for negotiations on March 9 , which he reached on May 3. The negotiations and necessary agreements with the Powers friends present there dragged on until May 20th. As a result, at the urging of the Elector, Holland and Spain announced that they would enter the war against Sweden. Otherwise he received no concrete support from the Holy Roman Empire and Denmark. The elector then decided to recapture the Mark Brandenburg from the Swedes alone. On June 6, 1675 he held an army display and left his camp on the Main . The advance of the 15,000-strong army to Magdeburg took place in three columns.

Campaign of Elector Friedrich Wilhelm (June 23 - June 29, 1675)

On June 21st, the Brandenburg army reached Magdeburg. As a result of inadequate clarification, the Swedes did not seem to have noticed the arrival of the Brandenburgers, and so Friedrich Wilhelm issued secrecy measures to maintain this tactical advantage. Only in Magdeburg did he receive precise information about the local situation. From intercepted letters it emerged that the union of the Swedish and Hanoverian troops and an attack on the Magdeburg fortress were imminent. After holding a council of war , the elector decided to break the Havellinie, which the Swedes had meanwhile reached, at the weakest occupied point, near Rathenow . As a result, he wanted to achieve a separation of the two Swedish armies in Havelberg and the city of Brandenburg.

On the morning of June 23 at 3 a.m. the army left Magdeburg. Since a success of the plan could only be expected if the element of surprise was used, the elector only proceeded with cavalry, which consisted of 5000 riders in 30 squadrons and 600 dragoons. In addition, there were 1350 musketeers who were transported on wagons to maintain their mobility. The artillery consisted of 14 guns of different calibers. In addition to the Elector, this army was led by Field Marshal Georg von Derfflinger, who was 69 years old at the time . The cavalry was led by General of the Cavalry Friedrich Landgraf zu Hessen-Homburg , Lieutenant General von Görztke and Major General Lüdeke. The infantry commanded the two major generals von Götze and von Pöllnitz.

On June 25, 1675 the Brandenburgers reached Rathenow . Under the personal leadership of the Brandenburg field marshal Georg von Derfflinger , the Swedish garrison, consisting of six dragoon companies, was able to be defeated in heavy street fights .

Also on June 25th, the main Swedish army marched from Brandenburg an der Havel to Havelberg , where the planned Elbe crossing was to take place. The overall strategic situation had changed significantly with the recapture of the important Rathenow square. Due to the separation of the two Swedish armies, it was no longer possible for the completely surprised Swedes to cross the Elbe near Havelberg. Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel, who was in Havelberg at an unsurfaced place and without supplies, gave the Swedish main army under Wolmar Wrangel the order to join him via Fehrbellin. In order to unite his troops with the main army, Field Marshal Carl Gustav Wrangel therefore broke on 16/26. June to Neustadt.

The Swedish headquarters seemed completely ignorant of the actual location and strength of the Brandenburg army. Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel now quickly retreated north to secure the lines of communication and, as ordered, to unite with the now separate Swedish advance division. The location of the Swedes in the case of Rathenows on June 15, jul. / June 25, 1675 greg. was prickly legacy . From there, due to the special natural conditions of the Mark Brandenburg at that time, there were only two routes to retreat. The shorter passage was endangered by the Brandenburg troops and the route conditions were considered extremely difficult. So the Swedes decided to take the route via Nauen , from where it was possible to avoid the three crossings: 1. Fehrbellin to Neu-Ruppin , 2. Kremmen to Gransee , 3. Oranienburg to Prenzlau .

But since both Oranienburg and Kremmen appeared to the Swedes to be occupied by the enemy, the only option left for the Swedes was to retreat to Fehrbellin. The Swedish general sent an advance detachment of 160 riders early to secure the passage via Fehrbellin.

The elector immediately had three patrol units set up to block the three possible crossings. The first division under Lieutenant Colonel Hennigs was deployed towards Fehrbellin, the second under Adjutant General Kunowski was sent to Kremmen, and the third under the command of Rittmeister Zabelitz was deployed against Oranienburg. They were given the task of using local hunters to reach the exits of the Havelland lynx on little-known paths through rough terrain in front of the Swedes . There the bridges were to be destroyed and the paths made impassable. For this purpose, these crossings were to be defended by armed soldiers and hunters.

Details are known only of the division's first platoon under Lieutenant Colonel Hennigs . He moved with 100 cuirassiers and 20 dragoons, led by a forester who knew the way, across the Rhinfurt near Landin and from there to Fehrbellin. Once there, taking advantage of the element of surprise, he attacked the crew of 160 Swedish cuirassiers on the hill covering the dam. About 50 Swedes were killed in the battle. A Rittmeister, a lieutenant and eight soldiers were taken prisoner, the rest escaped together with the commanding Lieutenant Colonel Tropp , but their horses stayed behind. The losses of the Brandenburgers amounted to 10 riders. The Brandenburgers burned the two Rhinbrücken bridges that connect the dam . Then the dam was also pierced to cut off the Swedes' route of retreat to the north.

Since no order had been given to hold the crossing because of its importance for the possible withdrawal of the Swedes, the Brandenburg department sought connection to the main army again. On the afternoon of March 17th / 17th June (after the actual battle near Nauen) she returned to the main army. The reports from this and the two other patrol units had reinforced the elector's intentions to deliver a decisive battle to the Swedes.

On June 27th there was the first battle between the Swedish rearguard and the Brandenburg vanguard in the battle near Nauen , which ended with the reconquest of the city. The two main armies faced each other in battle formation that evening. However, the position of the Swedes seemed too strong for a promising attack by the Brandenburgers and the Brandenburg troops seemed exhausted by the forced marches of the past few days. So the order of the elector was issued to retreat to the city of Nauen or behind the city and to set up camp there. On the Brandenburg side, they expected the decisive battle to begin at the gates of Nauen the next morning. The Swedes, however, used the night to retreat towards Fehrbellin. From the beginning of the retreat on June 25th until after the battle near Nauen on June 27th, the Swedes lost a total of around 600 men in their retreat and another 600 were taken prisoner.

Since the dam and the bridge over the Rhin had been destroyed the day before by the Brandenburg patrol department, the Swedes had to face the decisive battle. Lieutenant General Wolmar Wrangel had 11-12,000 men and seven cannons.

The Swedes, who were devastated in this encounter known as the Battle of Fehrbellin , managed to cross the restored bridge under cover of night. But their losses increased considerably during the retreat through the Prignitz and Mecklenburg . In the battle and the persecution that followed, 2,400 men were killed and 300 to 400 were taken prisoner, while 500 men died or were wounded on the Brandenburg side. Only in Wittstock did the Brandenburgers stop the pursuit.

consequences

The Swedish army had suffered a severe defeat and, particularly through the defeat at Fehrbellin, lost its previously recognized nimbus of invincibility. The remnants of the army were again on Swedish territory in Pomerania, from where the Swedish army had started the war.

The overall strategic position of Sweden deteriorated further when Denmark and the Holy Roman Empire declared war against Sweden in the following summer months. The possessions in Northern Germany ( Bremen and Verden Abbey ) were suddenly in danger. In the following years of war, Sweden, now on the defensive, had to concentrate on defending itself against the frequent attacks on its territories, which was only successful in Skåne .

The strategic plan of France, however, proved to be successful: Brandenburg-Prussia was still officially at war with France, but had withdrawn its army from the Rhine front and had to concentrate all further efforts in the war against Sweden.

literature

- Frank Bauer: Fehrbellin 1675. Brandenburg-Prussia on the rise to a great power. Vowinckel, Berg am Starnberger See and Potsdam 1998, ISBN 3-921655-86-2 .

- Samuel Buchholz : An attempt at a history of the Churmark Brandenburg from the first appearance of the German Sennonen up to the present day . Volume 4. Birnstiel, Berlin 1771.

- Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden . Volume 4: Until the Reichstag in 1680. Perthes, Gotha 1855.

- Friedrich Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm, the great elector, and his time. A history of the Prussian state during its government; in biographical . In: Prussia's heroes in war and peace. Volume 1.1. Hempel, Berlin 1855.

- Curt Jany: History of the Prussian Army. From the 15th century – 1914. Volume 1: From the beginnings to 1740. 2nd, expanded edition. Biblio Verlag, Osnabrück 1967, ISBN 3-7648-1471-3 .

- Paul Douglas Lockhart: Sweden in the Seventeenth Century. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke et al. a. 2004, ISBN 0-333-73156-5 .

- Maren Lorenz : The wheel of violence. Military and civilian population in Northern Germany after the Thirty Years War (1650–1700) . Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2007, ISBN 3-412-11606-8 .

- Martin Philippson: The great Elector Friedrich Wilhelm of Brandenburg. Part III [1660 to 1688] In: Elibron Classics , Adamant Media Corporation, Boston MA 2005 ISBN 978-0-543-67566-8 , (German, reprint of the first edition from 1903 by Siegfried Cronbach in Berlin).

- Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II of Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). A political biography. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-428-09497-2 .

- Ralph Tuchtenhagen : A Little History of Sweden. Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 3-406-53618-2 .

- Matthias Nistahl: The Reich execution against Sweden in Bremen Verden. In Heinz-Joachim Schulze (ed.): Landscape and regional identity. Contributions to the history of the former duchies of Bremen and Verden and the state of Hadeln (= series of publications of the regional association of the former duchies of Bremen and Verden. Volume 3). Stade 1989, pp. 97-123

Remarks

- ^ Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II of Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). A Political Biography , p. 233

- ^ A b Samuel Buchholz: Attempt at a history of the Churmark Brandenburg , fourth part: new history, p. 92

- ^ Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II of Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). A Political Biography , p. 238

- ^ Friedrich Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm, the great Elector, and his time , p. 128

- ↑ a b c Anonymous: Theatrum Europaeum . Volume 11: 1672-1679 . Merian, Frankfurt am Main 1682, p. 566

- ^ Curt Jany: History of the Prussian Army. From the 15th century – 1914. Vol. 1: From the beginnings to 1740. 2nd, supplemented edition: History of the Prussian Army. From the 15th century – 1914. Vol. 1: From the beginning to 1740. 2nd, expanded edition. P. 230

- ^ Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II of Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). A Political Biography , p. 234

- ^ Curt Jany: History of the Prussian Army. From the 15th century – 1914. Vol. 1: From the beginning to 1740. 2nd, expanded edition. P. 236

- ^ Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II of Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). A Political Biography , p. 239

- ↑ The strength of 16,000 men, which corresponded to the contractual agreements between France and Sweden of 1672, is u. a. stated in: Samuel Buchholz: Attempting a history of the Churmark Brandenburg , Part Four: New History, p. 92

- ↑ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. S. 603

- ↑ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. S. 602

- ^ Friedrich Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm, the great Elector, and his time , p. 127

- ↑ a b Friedrich Förster: Friedrich Wilhelm, the great Elector, and his time , p. 131

- ^ Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II of Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). A political biography , p. 251

- ^ A b Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag in 1680. P. 604

- ^ Michael Rohrschneider: Johann Georg II of Anhalt-Dessau (1627–1693). A political biography , p. 253

- ^ Curt Jany: History of the Prussian Army. From the 15th century – 1914. Vol. 1: From the beginning to 1740. 2nd, expanded edition. P. 238

- ↑ Friedrich Ferdinand Carlson: History of Sweden - up to the Reichstag 1680. P. 605

- ^ Curt Jany: History of the Prussian Army. From the 15th century – 1914. Vol. 1: From the beginning to 1740. 2nd, expanded edition. P. 239

- ↑ FraFrank Bauer: Fehrbellin 1675. BrandenburgPrussia departure as a great power , p 108

- ^ Frank Bauer: Fehrbellin 1675. Brandenburg-Prussia on the rise to a great power , page 112

- ^ Frank Bauer: Fehrbellin 1675. Brandenburg-Prussia's rise to a great power , p. 120

- ↑ Frank Bauer: Fehrbellin 1675. Brandenburg-Prussia's rise to a great power , p. 131