Gottorf giant globe

The Gottorf giant globe is a walk-in globe that was set up in the garden of the Gottorf Palace near Schleswig and is now in the Kunstkammer in Saint Petersburg .

The globe with a diameter of three meters, which was built between 1650 and 1664 by order of Duke Friedrich III. von Gottorf originated, became famous all over Europe. The construction of the globe was the responsibility of the ducal court scholar and librarian Adam Olearius , while the Limburg gunsmith Andreas Bösch carried out the work.

Other such hollow globes can be found in the Chicago Adler Planetarium and at the Robert Mayer Observatory in Heilbronn . Together with the modern replica in Gottorf, four hollow globes are known.

The globe house in the Neuwerkgarten

The globe was probably an important part of the planning of the Neuwerkgarten from a very early stage . While this was already being laid out from 1637, Duke Friedrich did not see the time had come until 1650 to start building the central point, the globe house . Seven years later the building was completed. The construction of the globe took much longer: the work was stopped in 1659 by the death of Duke Friedrich III. and the Swedish-Polish War interrupted and only ended in 1664.

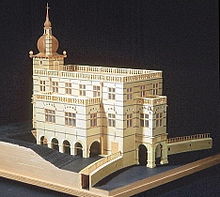

Adam Olearius was probably the architect of the globe house. It was aligned north-south at the apex of a wall that enclosed the semicircular so-called "globe garden" north of the Hercules pond. Outwardly it was a symmetrically constructed four-storey, cuboid brick building with a flat roof that could be walked on. Large, predominantly four-wing stone frame windows stood in the three or six-axis walls. The globe house had massive extensions on all four sides that reached up to the second floor; the northern extension protruded as a tower over the rest of the building and was crowned by an onion-shaped copper helmet. The extensions on the long sides were the result of a subsequent change in the building design.

The spatial concept of the building provided for two low basement floors, one above the other, above the main floor with the globe hall and finally the upper floor with two bedrooms, a cabinet and a larger hall to the south. The two upper floors were connected by a spiral staircase in the tower, which also led to the large flat roof. The level of the main floor with the main entrance in the north was level with the first garden terrace. The lower of the two cellars was at ground level with the globe garden in front of it to the south. With a floor area of 200 m² (without the extensions) and a height of almost 14 m (without the tower), it was a stately building for those times. Perhaps that is why it was occasionally given the name "Friedrichsburg". In the official language of Gottorf, however, the building was only called " Lusthaus "; it was only in the last decades of its existence that it was called "Globus House". With its cube-like structure and flat roof that can be walked on, the globe house corresponded to the contemporary summer houses in Italy, the Netherlands and Denmark. The shape of the building was supposed to look exotic, which is why it was sometimes referred to as the "Persian house". In terms of its structural details, however, the globe house still followed the forms of the Dutch Renaissance , as was common in Schleswig and Holstein at the time.

Little is known about the use of the globe house, although excavation finds testify to long meals in the building. After the death of Duke Friedrich III. however, it seems to have rarely been used. Accordingly, it showed numerous structural damage, which was due in particular to the leaky flat roofs. However, the large globe always remained a popular showpiece that was gladly shown to interested visitors.

The globe

The center and centerpiece of the globe house was of course the large globe . From the outside it represented the globe, inside it hid a planetarium that showed the starry sky and the course of the sun, including its movements, as they can be seen from the earth. Its special attraction was that you could get into it, sit there and let the stars circle around you without being moved yourself. The globe was the Duke's own invention, but the “scientific management” of this project was held by his court scholar and librarian Adam Olearius. The gunsmith Andreas Bösch, brought in from Limburg, finally put the Duke's idea into practice.

The globe was created at the same time as and in the building, its individual parts were made in a forge's workshop rented by the court on the Hesterberg and assembled in the globe house . For years, Andreas Bösch employed a group of craftsmen of seven to nine people, made up of blacksmiths, locksmiths, watchmakers, copper engravers , engravers , carpenters and painters and for whom external companies such as a Husum brass foundry were occasionally involved. Among them were the Gottorf watchmakers Nikolaus Radeloff and Hans Schlemmer, the Gottorf copperplate engraver Otto Koch and the cartographers Christian and Andreas Lorenzen, known as Rothgießer from Husum. Adam Olearius himself also worked as a cartographer with brush and pen.

In addition, the so-called “Sphaera Copernicana” was created between 1654 and 1657, which Andreas Bösch developed independently and built under his own direction. Apparently it was created as a complement and extension of the cosmological concept of the large globe and at a time when work on the globe itself was already well advanced.

Transport to St. Petersburg

The most famous - and most fateful - visitor to the Globe House was Tsar Peter the Great , who met the Danish King Frederick IV on Gottorf on February 6, 1713 in the course of the Third Northern War . Tsar Peter showed such great interest in the globe that only a few weeks later the large sphere - half spoils of war, half state gift - was sent to Saint Petersburg , where it arrived in 1717 after a four-year journey. Here the globe was placed in the tsar's art chamber . When it burned down in 1747, the globe also suffered severe damage, only its metal parts remained. In the same year it was restored on the orders of Tsarina Elisabeth under the direction of the scholar Michail Wassiljewitsch Lomonossow (1711 to 1765), whereby the meanwhile grown geographical knowledge was duly taken into account. Only the old entrance hatch of the globe was spared from the fire - it still shows the original painting of the 17th century with the Gottorf coat of arms. At the end of the 18th century, the astronomer Friedrich Theodor von Schubert carried out further repairs.

In Schleswig , in order to get the huge ball out of the globe house without dismantling, a large opening had to be punched into the wall on the west side. The building was thus robbed of its actual content and its fate sealed. From now on it only led a shadowy existence. All necessary repairs were only carried out half-heartedly and could not stop the ongoing decline. The building stood idle for a good 50 years until it was publicly auctioned for demolition in November 1768 by order of King Christian VII of Denmark . A master craftsman from Schleswig acquired the ruin; a year later nothing reminded of the globe house. In this way, a building was lost whose design, conception and program are probably unique in the history of architecture and technology .

A visit to the globe house

You entered the globe house through the main entrance adorned with a portal under the stair tower in the north. From there one came through a short corridor into the Globussaal, the floor area of which took up almost the entire floor. The room had numerous windows and was kept all white so that the globe appeared in full light. Under the green-painted windows there were lead panels painted in the style of Dutch wall tiles. The ceiling of the hall was stuccoed. The globe itself stood in a wide, accessible, twelve-sided wooden horizon ring , which was alternately supported by carved Hermes pillars and Corinthian columns . On its outside, the world known at the time - Europe, Africa, America and Asia - "... so fine as in the printed country charts" was drawn, with country borders outlined in color and with "all kinds of animals according to country type" and "fleets of ships [... ] Sea wonders and sea fishing ” . Globes from the famous Amsterdam map publisher by Willem Janszoon Blaeu and Joan Blaeu , with whom Adam Olearius had good connections, served as a template for the mapping .

You could climb into the globe through a small hatch and sit around a round table in the middle. Here you could see the starry sky - the stars were represented by over 1,000 ray-shaped brass-gilded nail heads, while the constellations were painted figuratively on the blue sky background. In addition, the globe contained special mechanisms to represent the annual movement of the sun and to drive a “world clock” that indicated the places on earth where noon or midnight was present. The globe could be set in motion either by a water drive in the cellar - so that it could "move and circumnavigate in the official 24 hours after heaven's walk [...]" - or by a manual drive from inside it, otherwise to speed up imperceptibly slow rotation. Of its kind, the Gottorfer Globus was the first accessible planetarium in history. At the same time he formed a large model of the old geocentric worldview according to Ptolemy . If the globe was out of order, the hatch was closed with a lid with the Gottorf coat of arms painted on it and a heavy green woolen cloth was pulled over the globe. On the doors in the Globussaal there were portraits of Nicolaus Copernicus and Tycho Brahe - a reminiscence of the astronomical luminaries of the time.

A door in the northeast corner of the Globussaal led into a small anteroom, in which a narrow, steep staircase led to the stair tower. There was a carved spiral staircase that led to the upper floor and further up to the roof.

While the main floor with the globe was open to the learned discussions of a larger group of visitors, the upper floor with its sleeping chambers and the ballroom had a more private character. The sleeping quarters were painted with green foliage decor, the ballroom was red. The ceilings of the rooms were stuccoed and partly also painted and gilded. French doors led out to the flat roofs of the extensions. The large roof terrace, which offered a splendid view of the gardens, was ideal for dining in the open air.

The furniture of the globe house consisted mainly of paintings, in particular the walls of the globe hall were decorated with numerous pictures with different themes. In the ballroom above there were paintings as well as a long table and 16 chairs. The duke's bedchamber was furnished with a large four-poster bed, while the valets slept in alcoves next door.

The two basement floors were only accessible from the outside. There was a large open hearth in the upper basement. After all, the globe house was also intended as a pleasure house, in which one did not want to miss out on the pleasures of the table. In the lower cellar was the watermill that was to give the globe its continuous drive. The power transmission through two floors was carried out by heavy brass worm gears and long iron shafts.

technology

The Gottorf globe was essentially a wrought iron construction. The sphere had a framework of 24 meridian rings , which were designed as T-irons and were stiffened by an equator ring. The outside of the frame was covered with copper sheet, which in turn received a multi-layered chalk-canvas primer, the top layer of which was polished. This gave a clean and smooth surface for the mapping, which is described as extremely fine. The inside of the globe was lined with thin pine strips on which a multi-layered chalk-canvas primer was also applied. The hatch cover in the wall of the globe was held in place by two spring locks. If there were people in the globe, the hatch remained removed.

The ball rotated around a fixed, heavy, wrought-iron axis. This was based on the floor in a millstone, at the top it was attached to a ceiling beam. The inclination of the axis corresponded - in contrast to the usual globe arrangement - with 54 ° 30 'the polar height of Schleswig. The reason for this inclination was that the planetarium inside the globe should represent the starry sky over Schleswig.

The ring-shaped bench construction was attached to the axis, which according to tradition offered space for ten to twelve people. It consisted of heavy iron rails, which were clamped together with heavy clamps on the axle and from there grew knot-like and cranked outwards. The “branches” not only supported the narrow bench, but also the running surface and a round table top in the middle. A wide brass horizon ring served as the backrest, bearing entries on the Gregorian and Julian calendar as well as astronomical data on the daily height of the sun.

On the tabletop in the center of the globe was a copper half-globe. It symbolized ( according to the cosmological concept ) the earth as the center of the heavenly vault. According to the inclination of the axis in the globe, Gottorf lay on the vertex of the table globe and thus formed the center of this artificial wonder world. Around the table globe was a horizontal ring with geographical length indications from various locations around the world. When the large globe was set in motion, two diametrical pointers stroked this ring and indicated where in the world it was midday or midnight.

The starry sky in the globe was - in keeping with the taste of the time - colored and figurative. Eight-pointed nail heads made of gold-plated brass represented the stars. They were divided into the traditional six size classes in order to indicate the real brightness relationships. Two candles on the table made the stars twinkle. Along the ecliptic in the celestial vault moved a roller bearing toothed ring on which a sun model made of cut crystal was mounted. The sun performed both its daily (rising and setting) and its annual movement (changing sun heights and rising and setting azimuths in the course of the year). A meridian half-ring with a degree scale arched over the viewer. The course of the moon and planets could not be included in the mechanical concept of the globe due to their complicated orbital movements (migration of nodes , planetary loops ).

There were three gears at the south pole of the interior of the globe . One of them moved the "world clock" on the table top over long waves and a planetary gear set the sun. The third was needed for the power transmission to the hand drive, because the globe could be moved from inside with a hand crank; the strength of one finger was enough. One rotation took about 15 minutes, which was enough to show the visitor all the celestial movements of a day (as they could be seen from Gottorf). Of course, the position of the sun model could be adjusted to simulate other seasons as well. It was therefore the first accessible planetarium in history, which demonstrated the celestial events "live" to the visitor.

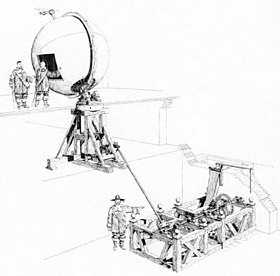

Another unusual drive option gave the globe the ability to display the daily rotation "in real time". In the basement of the globe house there was a wooden water wheel, which transmitted its movements to the globe via a four-stage worm gear reducer. The water for the mill was brought to the house through lead pipes, in the basement it fell onto the water wheel and flowed through an underground outlet into the Hercules pond. The wheels and worms, some of which were very heavy, were all made of brass, which led to heavy friction losses. The movement was transmitted through two floors by means of long wrought iron shafts. The uppermost gear section was at the foot of the globe axis and was covered there by a painted, sloping wooden box. Presumably, however, the water drive served more to demonstrate technical ability and less for educational demonstrations. 50 years after the completion of the globe house, it was in serious disrepair.

The Sphaera Copernicana

While the construction of the giant globe was nearing completion, Andreas Bösch was already starting his new project, the so-called Sphaera Copernicana. Apparently it was supposed to complement and expand the concept of the big globe. In its interior, this formed a mechanical model of the geocentric world system according to Ptolemy , which, however, had already been recognized as antiquated at the Gottorf court. So it made sense to create a demonstration model that showed the real conditions in the universe according to Copernicus ' theory - a "Sphaera Copernicana".

It is not surprising that the Sphaera Copernicana has some constructive and representational parallels to the large globe. However, at the Sphaera Copernicana “there was even more art to be seen than at the big Globo.” Here the imposing size and the original concept aroused amazement and admiration, there the complicated gear train, which - driven by a single clockwork - 24 different functions and displays at the same time steered.

Although one must assume that Adam Olearius was also in the background during the construction of the Sphaera Copernicana, apparently Andreas Bösch was solely responsible for the technical development of the work. Of course, he also employed numerous people here, for example Hans Schlemmer supplied the powerful clockwork for the drive and Otto Koch took care of the design of the constellations. After its completion, the Sphaera Copernicana was placed in the Gottorf Art Chamber , later in the Gottorf Library.

In the course of the clearing of the palace, the Copernican armillary sphere came to the Royal Chamber of Art in Copenhagen in 1750 . There it should be scrapped in 1824; In 1872 it came to the National History Museum at Frederiksborg Castle in Hillerød in an adventurous detour . It can still be seen there today. The Sphaera Copernicana has recently been carefully restored (Atelier Andersen in Virket, Denmark). Not only could missing parts be added or returned to their original place, but their original color scheme could also be partially regained.

The Sphaera Copernicana is much smaller than the globe. Its diameter is 1.34 m and its total height is 2.40 m, but it is technically much more sophisticated than the large globe. It rests on a wooden base case in which a very powerful spring clock mechanism is hidden. It has a walking mechanism with a running time of eight days as well as a quarter-hour and an hour striking mechanism , but at the same time it has to keep 24 movements in the armillary sphere itself going. The main drive shaft runs vertically from the center of the movement through the entire armillary sphere. The shaft can be uncoupled when the movements in the armillary sphere - independent of the clockwork - are to be demonstrated by a manual drive.

In the center of the armillary sphere, a shiny brass ball embodies the sun. Around them are placed and guided toothed brass rings, which represent the orbits of the planets known at the time (from inside to outside: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn). The planets themselves are represented by small silver figurines that hold their respective symbols in their hands. They move around the sun in the same time periods as the real planets in the solar system. Sophisticated gear systems ensure the correct reduction from the vertical drive shaft to the planetary ring. The position of each planet can be corrected manually.

The earth's orbit is the only one that does not have a silver figure. Here a miniature armillary sphere embodies the earth and the moon. The two celestial bodies are modeled as spheres. The earth performs its daily rotation, with the earth's axis always pointing in the same direction to the north celestial pole. The moon circles the earth in 27.3 days and shows its phases. The time of day can also be read from a small dial on this miniature armillary sphere.

The outer enclosure of the planetary system is formed by two armillary spheres, the inner one being movable while the outer one is fixed. Both are made up of six vertical half-rings and a horizon ring. The inner sphere embodies the so-called “Primum mobile”, which at the time explained the slow shift between the point of spring and autumn on the ecliptic . Two brass bands with engraved graduated scales make this movement visible. One orbit of the Primum Mobile takes 26,700 years.

The outer fixed sphere has the constellation figures on its rings. She thus embodied the vault of heaven visible from earth. Of the original 62 constellation figures, only 46 are left. They are made of sheet brass and sit on the inside of the rings of the sphere. Their insides are engraved and given their respective Latin names. A celestial globe from Willem Janszoon Blaeu's Amsterdam map publisher could be identified as a template for the figurative representation of the constellations. The constellations have small riveted, six-pointed silver stars on their inner sides, which - according to their actual brightness - are six different sizes.

The hand drive for the armillary sphere consists of an extendable and lockable shaft onto which a crank can be inserted. If you turn it, the movements in the Sphaera Copernicana - just like in the giant globe - could be significantly accelerated so that they were visible to the eye.

The whole armillary sphere is crowned by an indicator for different day divisions and the "Sphaera Ptolemaica" on it. The display unit consists of three concentric cylinder walls that slide in front of each other like scenes. A small solar disk, which changes its height every day, passes in front of the innermost cylinder. Based on the backdrop and the sun, the times of the day can be read according to civil, Roman-Babylonian and Jewish times. Since the latter two orientated themselves according to the course of the sun, their beginnings of the day shift by a few minutes each. For this reason, astronomers have measured the day from midnight to midnight since ancient times. This division gradually established itself in bourgeois life in the 16th and 17th centuries. The different times of the day may have played a certain role at the Gottorfer Hofe in the 17th century, even though they were more of a scientific interest.

At the top of the display is finally the aforementioned small Ptolemaic armillary sphere, the structure and movements of which is a complete miniature representation of the giant globe. In the middle there is a small globe that stands still according to the geocentric world system. Around them - similar to the tabletop in the giant globe - lies a horizontal disk on which a compass line rose is engraved. The sphere around it symbolizes the starry sky and moves around the earth once a day. On the inside of the sphere, a ring of teeth moves that carries a sun figure through the ecliptic once a year.

Historical reconstruction

It is thanks to the globe's unusual size and conception that much has been reported about it from the most ancient to the recent past. But none of the reports gave an exact picture of how the Gottorf system was really designed. There was nothing to be gained from the historical illustrations either. So the level of knowledge was necessarily limited to the knowledge of the builders of the globe, the construction time, the other circumstances of the time and to more or less superficial descriptions of the globe and the building in which it stood. None of the descriptions allowed any conclusions to be drawn about the exact position of the globe in the building or other structural-technical details or the appearance of the globe house.

Only an extensive inventory of the ducal residence's buildings, which was created around 1708 in the course of a general taxation and which gave an account of the structural value and condition of all courtyard buildings and gardens, provided concrete information. In the case of the globe house, too, almost everything that was found in and on the building was recorded down to the last nail. The quality and clarity of the inventory was able to almost replace what was previously missing in the image sources.

Based on the inventory text, Felix Lühning began to prepare a reliable graphic reconstruction of the globe house in 1991. This included, above all, extensive archive research that concentrated on the structural and technical aspects of the Globus facility - in particular the accounts of the ducal pension chamber for the construction, repairs and maintenance of the Globus house. A wealth of other information emerged from them with regard to the type and quantity of the components supplied for the globe and the house as well as the costs, the number and the names of the people involved in the construction. An excavation and measurement of the globe house foundations confirmed the measurements from the written sources.

The globe itself is still present in its essential structural parts in Saint Petersburg, so that measurements were possible and the reconstruction of missing components did not present any difficulties. Existing doubts about technical details were checked or dispelled by comparisons with the Sphaera Copernicana in the National History Museum at Frederiksborg Castle in Hillerød, Denmark. Unambiguous models could also be assigned to the lost original version of the mapping (earth and sky). The reconstruction of the globe could therefore be made with a probability bordering on certainty, both in terms of its construction, its technical-astronomical content and its design. At the end of the research, there was extensive material that first had to be sorted and then put together like a mosaic from a technical and constructive point of view and built into a coherent whole.

As a result, Felix Lühning presented a reconstruction of the globe house in the Neuwerkgarten in 1997 in drawings and models, which is mainly based on an intensive study of written sources. About 80% of these document the presence of the building materials, 90% the sequence and distribution of the rooms, 80% the dimensions and 50% the appearance of the building and its individual parts. Here, however, a finer gradation must be made: certain components are 100% secured thanks to excavation finds, other parts can be proven to 90% based on precise descriptions and examples from the workshop of the same master that have been preserved elsewhere (especially the portals), while other components are not at all and had to be reconstructed based on contemporary models and in accordance with the structural engineering solutions customary in the 17th century (especially beam layers). The outer and inner design (masonry, wall anchors, windows, stucco, decorative elements and the like) of the reconstruction is always based on the simplest form of contemporary models, as long as clear evidence is missing. The floor plan of the building is 100% secured. The latest excavations, which the State Office for Prehistory and Protohistory were able to carry out with considerably more technical means than Felix Lühning had at the time, may necessitate a revision of the previous reconstruction in the basement. In return, however, they will provide reliable findings in those areas in which Felix Lühning was still dependent on guesswork during his work.

Only the water drive for the globe is a special case. The main gear parts (gears, worms, shafts) can all be documented in the archives and allow good conclusions to be drawn about their dimensions from the cast weights given in the sources, and the location of some components in the building has also been described. However, since the machinery was ultimately a singular phenomenon and had no role models, Felix Lühning had to make 60% of his own speculations.

Globus and Neuwerkgarten today

In the past decade, great efforts have been made by the monument conservationists to expose the grounds of the Neuwerkgarten in order to make the magnificent gardens visible and comprehensible again. However, the shortage of money and difficult terrain ensured that the work took a long time. Felix Lühning's work on the globe was a given occasion to put into practice the wish , which has existed since the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation was founded , to restore the terrace garden of Gottorf Castle in its baroque splendor - with globe house and globe. Garden, globe and globe house form an integral part of the historical connection with the palace complex and have never been fundamentally redesigned in its long history. The plans, however, did not envisage a historically authentic reconstruction, but a design-oriented solution in which the aesthetic aspects were predominantly in the foreground (architects Hillmer & Sattler and Albrecht , Berlin). The implementation of this project was made possible through the commitment of various foundations. The ZEIT Foundation Ebelin and Gerd Bucerius , the German Federal Environment Foundation and the German Foundation for Monument Protection financed the restoration of the garden, while the support of the Hermann Reemtsma Foundation Hamburg enabled the construction of the new globe house and a faithful replica of the Gottorf globe. In May 2005, the globe house with the new Gottorf globe and the first stage of expansion of the garden were opened with a large participation of the population and the press. The garden and globe house have since become an internationally recognized attraction.

Since 2019, the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums have been offering new educational services in the Globushaus. In addition to newly designed exhibition graphics with information on the globe, globe house, baroque garden and early Baroque plant culture, a virtual reality film shows the history of the globe. In the six-minute film, Adam Olearius and Duke Friedrich appear in the imagery of the baroque stage theater. The 360-degree film places the construction of the globe in the social context of the Thirty Years War , introduces the protagonists and their living environments, shows the trades involved in the construction and visualizes the complex mechanics of the globe. Since the beginning of 2020, visitors have been able to explore excerpts from the film and additional information about the giant globe and globe house from home in a 360-degree application on the museum's website.

See also

literature

- Herwig Guratzsch (ed.): The new Gottorfer globe. Koehler & Amelang, Leipzig 2005, ISBN 3-7338-0328-0 .

- Angel Petrovic Karpeev: Bol'soj Gottorpskij globus (The great Gottorf globe). Muzej Antropologii i Etnografii Imeni Petra Velikogo (Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography), St. Petersburg 2003, ISBN 5-88431-016-1 (Russian)

- Felix Lühning: The Gottorfer Globe and the Globe House in the 'Newen Werck'. Catalog volume IV of the special exhibition “Gottorf in the Glory of the Baroque”. Schleswig 1997.

- Felix Lühning: The whole universe at a glance - the Gottorfer Sphaera Copernicana by Andreas Bösch. In: Nordelbingen . Contributions to art and cultural history. ISSN 0078-1037 , vol. 60 (1991), pp. 17-59.

- Yann Rocher (Ed.): Globes. Architecture et science explorent le monde . Norma éditions / Cité de l'architecture, Paris 2017, pp. 42–45, ISBN 978-2-37666-010-1 .

- Ernst Schlee : The Gottorf Globe Duke Friedrich III. Westholsteiner Verlagsanstalt, Heide 2002, ISBN 3-8042-0524-0 .

Web links

- Schleswig-Holstein State Museums Foundation Gottorf Castle

- The Gottorfer Globus - a baroque world theater - Website by Felix Lühning about the Gottorfer Giant Globe

- Virtual tour of the globe, globe house and baroque garden

Individual evidence

- ↑ New 360-degree film: How the idea to build the globe came about. In: Websites of the Schleswig-Holstein State Museums. Retrieved June 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Virtual tour - Discover the Gottorf globe and baroque garden. Retrieved July 20, 2020 .

Coordinates: 54 ° 31 ′ 2 ″ N , 9 ° 32 ′ 24 ″ E