Dinslaken

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 51 ° 34 ' N , 6 ° 44' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | North Rhine-Westphalia | |

| Administrative region : | Dusseldorf | |

| Circle : | Wesel | |

| Height : | 30 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 47.66 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 67,373 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 1414 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postcodes : | 46535, 46537, 46539 | |

| Area code : | 02064 | |

| License plate : | WES, DIN, MO | |

| Community key : | 05 1 70 008 | |

| LOCODE : | DE DIN | |

| City structure: | 10 settlement districts | |

City administration address : |

Platz d'Agen 1 46535 Dinslaken |

|

| Website : | ||

| Mayor : | Michael Heidinger ( SPD ) | |

| Location of the city of Dinslaken in the Wesel district | ||

The city Dinslaken [ dɪnslaːkn̩ ] is at the lower Lower Rhine in the northwest of the Ruhr area in North Rhine-Westphalia and is a large district town of Wesel in the administrative district of Dusseldorf .

geography

location

Dinslaken borders Walsum ( Duisburg ) and Oberhausen in the south and is about 13 km from Wesel in the north-west. The Hohe Mark-Westmünsterland Nature Park borders in the east .

Expansion of the urban area

The total area of the urban area is around 48 square kilometers. The maximum north-south extension is 8.5 kilometers, in a west-east direction it is 12.4 kilometers. The highest point of the urban area is 113.0 m, the lowest point 20.5 m above sea level. NN .

Neighboring communities

| The city of Dinslaken borders the municipality of Hünxe in the north, the independent city of Bottrop in the east, the independent city of Oberhausen in the southeast, the independent city of Duisburg in the south and the cities of Rheinberg and Voerde in the west and northwest . |

City structure

Spatially, the urban area is divided into the following ten settlement districts (in brackets the population figures on December 31, 2018 according to the city's website, i.e. possibly different from the information provided by the state office)

- Averbruch (6,551)

- Flowers quarter (6,947)

- Eppinghoven (4,138)

- Feldmark (Dinslaken) (12,311)

- County (577)

- Hagenviertel (5,278)

- Hiesfeld (15,763)

- City Center (8,682)

- Lohberg (5,926)

- Oberlohberg (4,524)

Location on the Rhine

Dinslaken and the surrounding area were always in the area of influence of the changing bank lines of the Rhine as a result of floods, landings, demolitions and Rhine shifts. The map by the cartographer Johann Bucker from 1713 shows the typical city silhouette (with the broken tower) and the mill positioned to the side. At that time, the riverbed largely corresponded to the current course of the river. However, on the other western side of the Rhine near Rheinberg there was still an arm of the old Rhine, which only largely silted up in the course of the 19th century and is now only represented as a cave and an old stream.

history

middle Ages

The starting point of the historical development of Dinslaken will have been a moth , a residential hill with a moat and protective wall, on the site of today's castle. The name Dinslaken is explained by the pools and sheets that existed in the city until the 1950s . In the 12th century, Dinslaken was first mentioned in a land and interest register of the Werden monastery as “Lake juxta instincfeld” (Lake near Hiesfeld). In the same period, a fort was built, which was expanded into a castle in 1420 and used as a "witches" prison in modern times. As early as 1273, Count Dietrich VII von Kleve granted the town town rights . During this time, Dinslaken traders concentrated mainly on the production and sale of cloth and linen . On September 21, 1412, Count Adolf II of Kleve issued a certificate in which he granted the town of Dinslaken a "Wollenamt" (a cloth makers' guild ). The Marienkamp convent was established before 1433 . In 1478 Dinslaken received market rights and joined the Hanseatic League in 1540 .

Renaissance

During the Eighty Years War , Dinslaken Castle was captured by Dutch troops and burned down in 1627 , but was later rebuilt. It was not until 1770 that the tower of the castle was badly damaged by lightning and the castle was converted into the seat of the rent master .

In 1709 a messenger post from Wesel first mentioned the name “Dinslaken”, and from 1712 there was already a regular mail car connection from Düsseldorf via Dinslaken to Wesel. In 1753 the city became the seat of a collegial regional court in the Duchy of Cleves . In 1784 Dinslaken had 870 inhabitants.

19th century

When Dinslaken fell back to Prussia after the Napoleonic Wars in 1816 , the Dinslaken district was founded and in 1823 merged with the Essen district to form the newly created Duisburg district. A district of Dinslaken only existed again on April 1, 1909, after the area had belonged to the Mülheim an der Ruhr district from December 8, 1873 and to the Ruhrort district from April 20, 1887 . During the March Revolution of 1848 a civil guard was formed to maintain law and order; on May 4, Prince Wilhelm of Prussia (later Kaiser Wilhelm I ) visited the city.

In 1850, in the course of industrialization, a glue factory was built , later a spark plug factory , and in 1873 an iron foundry . The Dinslakener Burg was acquired in 1853 by the de Fries family, who established agriculture and a schnapps distillery in it . The economic importance of Dinslaken can be seen primarily from the expansion of the infrastructure. In 1855 Dinslaken had 1752 inhabitants. On July 1, 1856, after a construction period of only two years, the Oberhausen –Dinslaken section of the Holland route was put into operation by the Cöln-Mindener Eisenbahngesellschaft and, as a result, stagecoach traffic was discontinued. With the outbreak of cholera in 1866/1867, the population decreased temporarily. In 1871, 2147 people lived in Dinslaken. The St. Vinzenz Hospital was founded in 1883, the Dinslaken volunteer fire brigade followed in 1890, as did the local branch of the SPD . In the same year the Kolping Family was formed as a journeymen and workers' association.

Over the year 1884, more than 10,000 animals were presented for the first time at the Dinslaken cattle market , which had already provided an economic boom in previous years and made Dinslaken a center on the Lower Rhine. In 1896 a new district court was completed, which was later to be used as the town hall. In the same year August and Josef Thyssen founded an oHG in Dinslaken ; In 1897 the construction of the "Deutscher Kaiser" rolling mill began . In the same year the first sports clubs in Dinslaken came into being: the men's gymnastics club "Rheinwacht Dinslaken" and the gymnastics club "Gut Heil".

1900-1929

In 1900 the Dinslaken city council decided to build a water and gas works as well as the repurchase of the Dinslaken castle, while the first tram from Dinslaken to Duisburg-Neumühl went into operation. The first street lamps were erected three years later; In 1906 the construction of the " Lohberg " colliery , which lasted until 1912, began , where coal could be mined for the first time in 1909. On April 1, 1909, another district of Dinslaken was established. In the same year the former castle complex was transformed into a district building; However, before the first work could begin, parts of the facility were destroyed in a fire. The livestock market became even more important, so that in the same year 33,500 animals were offered. The "Dinslakener Generalanzeiger" was the first daily newspaper to report from Dinslaken since 1908, and in 1910 a public library was set up. In 1913 Dinslaken had more than 10,000 citizens for the first time. The following year, the Lohberg colliery produced 27,000 tons of coal. A tram line from the train station to Lohberg went into operation (1914). During the First World War , the cattle shed built in 1914 was converted into a prisoner of war camp and in 1916 a new train station was put into operation. In 1917 the city council granted both August Thyssen and Paul von Hindenburg honorary citizenship. In the same year, the previously independent municipality of Hiesfeld was incorporated into Dinslaken.

At the end of the war, a workers 'and soldiers' council met in 1918, and the city council decided to set up a protective guard. During the elections for the National Assembly in 1919, conflicts with communist groups in particular led to unrest in Dinslaken, which culminated in the shooting of a worker in Lohberg. In the following year, insurgent workers and soldiers occupied the city under the name " Red Army "; the operations director of the Lohberg colliery fell victim to an assassination attempt that same year. When the Ruhr area was occupied by France and Belgium on January 11, 1923 because of backward reparation payments under the Versailles Treaty , Belgian troops also marched into Dinslaken. The city, economically weakened by the rising inflation and mass unemployment , began to print its own money in the same year, but shortly afterwards the Rentenmark was also introduced in Dinslaken . The general unrest, particularly in Lohberg, continued, however, political murders broke out, and the Lohberg colliery came to a standstill.

In 1924 the Belgian occupiers evacuated Dinslaken and coal mining in Lohberg was resumed. In the same year Konrad Adenauer visited the city, which was slowly recovering from the confusion of previous years. In 1926 the August-Thyssen-Hütte and the Dinslaken rolling mill were merged into the newly founded "United Steelworks AG". The building cooperative "Hausbau GmbH" was founded two years later. In 1930 another tram line was set up by the Ruhrorter Straßenbahn AG district to Hiesfeld.

National Socialism and World War II

A local branch of the NSDAP was established in 1930, and the Hitler Youth organized a short time later. As a countermovement, the Kampfbund against Fascism was formed in 1931 with the support of the KPD . In 1933 the city council finally met to the exclusion of parliamentary groups from the KPD and SPD. Thereupon the systematic discrimination against the Jewish population began, which was officially excluded from the cattle markets in 1935. The synagogue and the Jewish orphanage were destroyed during the Reichspogromnacht on November 9, 1938 , as were the shops and houses of Jewish citizens. The Jewish school was closed. On the morning of November 10, 1938, one day after the night of the Reichspogrom, 35 orphans from Dinslaken were driven out of the city together with one of their teachers and educators using a cart that the eldest of the children had to push in front of the numerous townspeople gathered. Their whereabouts are largely unclear to this day. Their path of suffering led through Cologne, Holland and Belgium. Few of the children are believed to have survived the displacement. Jewish men under the age of 60 - many of them highly decorated soldiers from the First World War - were deported from Dinslaken to Sachsenhausen concentration camp and to Dachau . The orphanage building was used by the NSDAP in the following years - today a memorial stone commemorates the events at this point. A sculpture by the Dinslaken artist Alfred Grimm near the Dinslaken town hall also commemorates the so-called Jewish train, the children's train . In 1942, none of the former 250 Jews lived in the city.

At the outbreak of war in 1939 there were around 7,480 apartments in Dinslaken.

During the Second World War , parts of the Kirchhellener Heide were expropriated for the construction of a field airport ; as early as 1940 Dinslaken was the target of Allied bombing raids . In 1944 these were almost part of everyday life and reached their peak in June when 130 high-explosive bombs fell on the city. In the air raid on Dinslaken on March 23, 1945, in which Allied bomber squadrons finally shot the place “ready for a storm”, 511 people died, including 40 slave labor (source: City Archives, March 22, 2005). A total of 739 civilians and 165 forced laborers were killed in Dinslaken during the Second World War. Dinslaken was more than 80 percent destroyed. On the morning of March 24, 1945, the 79th US Infantry Division advanced across the Rhine to Dinslaken as part of Operation Flashpoint as part of Operation Plunder and was finally able to take it. In April, the mining of the Lohberg colliery was resumed in occupied Dinslaken. In May the US troops withdrew. Dinslaken became part of the British zone of occupation . At the same time, the first refugees from the eastern areas occupied by Soviet troops were looking for a new home in Dinslaken.

Post war history

In 1946 the military government appointed the new district council . On April 1st, a new municipal code based on the British model came into force, and the first free and secret district elections took place in the middle of the month. District Arnold was Verhoeven. In September the citizens of Dinslaken were able to elect a new city council for the first time. In October Wilhelm Lantermann was elected mayor . An adult education center was also founded under the sponsorship of the Dinslaken district .

In 1947 the iron strip mill, formerly the most modern and efficient in Europe, was dismantled, in 1948 the garbage disposal was modernized and the last horse-drawn vehicles in the city's fleet were finally replaced by trucks. In the same year, the Emscher was diverted to a new river bed on the south-western outskirts. At the same time, the replacement of the previous gas street lamps with electric lamps began, while the reconstruction of the city after the destruction of the war continued. In 1950 Dinslaken had 32,651 inhabitants as the result of a population, occupation, housing and workplaces census. The cattle market, which was still the economic mainstay of the city a few decades ago, was closed in the same year for reasons of profitability . 1954 opened with the harness racing track at Bear Kamp today the only half-mile track in Germany and in 1959 Heinrich Luebke as a member of parliament of the circle Dinslaken the President elected.

After Banat Swabians and Croatian Germans had already settled in the Hiesfeld district in 1955 , Italian guest workers in particular were wooed for mining and industry in 1960, and later Greeks , Koreans and Turks as well . In 1961 the population was 45,486, in 1969 it was 55,300. From 1971 resettlers from Poland ensured further population growth. In 1973 Wilhelm Lantermann died after 26 years as mayor, his successor was Karl Heinz Klingen. In the same year Dinslaken celebrated its 700th city anniversary.

In 1975 the Dinslaken district was merged with parts of the Moers and Rees districts to form the new Wesel district as part of the second reorganization program . Dinslaken loses the seat of the circle. In 1978 Dinslaken passed the 60,000 mark. Commemorative plaques were erected in 1981 to commemorate the former Jewish community of Dinslaken and the Jewish citizens who fled or deported. They commemorate the former orphanage and the destroyed synagogue. Since 1993, a memorial by the Hünx artist Alfred Grimm has also been to commemorate the formerly existing Jewish community. More than 30 Jewish guests from all over the world, mostly former citizens of Dinslaken, were invited to a week-long visit to the city for the unveiling of the memorial.

In 1991 Dinslaken hit the headlines nationwide. In May, around 270,000 liters of petrol seeped into the ground from a broken pipeline on Federal Motorway 3 . Shortly afterwards, a gas pipeline was damaged in Hiesfeld, presumably due to mining, but the leak was discovered and sealed in good time. Miners from the Lohberg colliery went on a hunger strike 1000 meters underground in protest against the coalition policy of the federal government , which was soon called in other mines in the region. In 1996, warning fires burned for over 100 days, as the miners of the Lohberg-Osterfeld colliery saw their jobs endangered by the restrictive coal policy. In 1997 Dinslaken passed the 70,000 mark. At the end of 2005 the Lohberg-Osterfeld colliery was closed.

With the series “Local Heroes”, Dinslaken started the program for the European Capital of Culture Ruhr 2010 in January 2010 as the first municipality to participate in the Capital of Culture year .

The district of Dinslaken-Lohberg was known for its Salafist jihadist scene . Since 2016, Dinslaken and the term "Lohberger Brigade" no longer play a role in the annual reports on the protection of the constitution of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.

In July 2016, the newly built city archive was opened in Dinslaken's old town on Elmar-Sierp-Platz opposite the Voswinckelshof.

Incorporations

On July 1, 1917, the northern part of the then municipality of Hiesfeld was incorporated. On January 1, 1975, the Eppinghoven district of the city of Walsum and an area of the municipality of Voerde (Lower Rhine) were added.

Outsourcing

On January 1, 1975, a part of the area with then about 800 inhabitants was assigned to the city of Duisburg.

Coat of arms, banner and logo

| Blazon : “In silver (white) a red gate castle withan open gate in the crenellated wall rising on both sideswith three towers ; the middle one is wider, higher and tinned , the slimmer side towers have spherical points. " | |

| Justification of the coat of arms: The coat of arms re-awarded by the Prussian State Ministry in 1928 is derived from the oldest main seal from the time after the town was raised by Count Dietrich IV of Kleve in 1273. It expresses the fortification of the Klevian city. |

As a flag (banner), the city of Dinslaken uses the colors red and white with the described coat of arms.

Dinslakener Platt

Dinslakener Platt , the dialects of the districts as well as the dialects of the neighboring communities, are based on the Lower Franconian languages that were spoken at the time of the early medieval expansion of the Franks on the Lower Rhine. The dialects between Emmerich and Duisburg / Mülheim-Ruhr are assigned to the North Lower Franconian spoken north of the Uerdinger line (also called Kleverländisch ). It is characterized by the use of “ek” for the personal pronoun “I”. South of this line, in South Lower Franconian (also called East Limburgish ), “isch” or “esch” is spoken instead of “I”. The Benrath line (maake-maache distinction) runs even further south, dividing the southern Lower Franconian from the Middle Franconian (with the Ripuarian dialects , including Kölsch ). East of Oberhausen also runs the unit plural line to the Westphalian . Although Dinslakener Platt is cultivated in clubs and dialect circles, the number of dialect speakers is constantly falling. Younger people are increasingly using a colloquial language called Niederrheinisches Deutsch ( Lower Rhine German ) , with elements of what is known as Ruhr German - called Regiolekt by scientists .

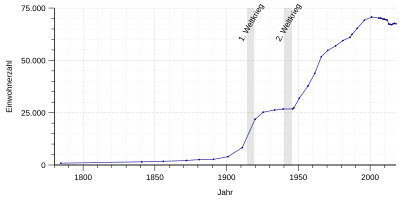

Population development

Until the 19th century, Dinslaken was a small town with a few hundred inhabitants. The population grew slowly over the centuries and fell again and again due to the numerous wars, epidemics and famine. In 1784 870 people lived in the city, by 1890 the population rose to 2,700. With industrialization and the development of mining in the 20th century, population growth accelerated.

In 1917, the incorporation of the greater part of Hiesfeld (9,914 inhabitants in 1910) brought Dinslaken an increase from 9,000 people to 20,000 inhabitants. In 1965 Dinslaken had 50,000 inhabitants. In 2003 the population reached its historical high of 71,193. On June 30, 2006, the “ official population ” for Dinslaken was 70,127 according to updates by the State Office for Data Processing and Statistics North Rhine-Westphalia (only main residences and after comparison with the other state offices).

The following overview shows the number of inhabitants according to the respective territorial status. These are census results (¹) or official updates from the State Statistical Office. From 1871, the information relates to the “local population”, from 1925 to the resident population and since 1987 to the “population at the location of the main residence”. Before 1871, the number of inhabitants was determined according to inconsistent survey procedures.

|

|

|

¹ census result

Denomination statistics

According to the census in 2011, 34.0% of the population were Roman Catholic , 32.6% Protestant, and 33.3% were non-denominational , belonged to another religious community or did not provide any information. The number of Protestants and Catholics has fallen since then. As of December 31, 2019, 20,109 inhabitants (28.5%) were Protestant and 21,606 (30.7%) were Roman Catholic . 28,744 (40.8%) belonged to other denominations or religious communities or were non-denominational . In the previous year, 29.1% were Protestant, 31.1% Catholic and 39.8% belonged to other denominations or religious communities or were non-denominational.

politics

City council

The 46 seats in the city council (2009: 56) are distributed among the individual parties as follows according to the results of the 2014 local elections :

| Party / list | Seats |

| SPD | 20th |

| CDU | 13 |

| GREEN | 4th |

| LEFT | 3 |

| FDP | 1 |

| ubv | 3 |

| DIN offensive | 1 |

| AWG | 1 |

Mayor since the 19th century

The names of the mayors of Dinslaken have been known since the 15th century, each separately for the old town and the new town. There has been a joint mayor since the 19th century.

- 1799 to 1806/1807 Johann Peter Romberg

- 1806/1807 to 1810 Friedrich Wilhelm Cotta

- 1811 to 1823 Peter Heinrich Noot

- 1823 to 1825 Jean Leo de Brauin

- 1825 to 1848 Carl Hermann te Peerdt

- 1848 to 1851 Melchior Julius von Buggenhagen

- 1851 to 1862 Otto Wilhelm Kurgaß

- 1863 to 1866 Melchior Julius von Buggenhagen

- 1866 to 1871 August Bilcken

- 1872 to 1892 Tilman Berns

- 1892 to 1895 Karl Bernsau

- 1895 to 1898 Paul Berg

- 1899 to 1911 Ernst Otto Leue

- 1911 to 1923 Max Saelmans

- 1924 to 1934 Eduard Hoffmann

- 1935 to 1944 Kurt Jahnke ( NSDAP )

- 1944 to 1945 Fritz Lüttgens (NSDAP)

- 1945 Josef Zorn ( center )

- 1945 to 1946 withered

- 1946 to 1973 Wilhelm Lantermann ( SPD )

- 1973 to 1993 Karl Heinz Klingen (SPD)

- 1994 to 1995 Kurt Altena (SPD)

- 1995 to 1999 Wilfrid Fellmeth (SPD)

- 1999 to 2009 Sabine Weiss ( CDU )

- since 2009 Michael Heidinger (SPD)

Sabine Weiss was the first directly elected mayor of Dinslaken and held the office from 1999 to 2009, until she won a direct mandate for the German Bundestag.

The current mayor of Dinslaken is Michael Heidinger (SPD), succeeding Sabine Weiss (CDU) since the mayoral election in 2009. He was re-elected in 2014 with 60.76% of the valid votes.

Town twinning

Dinslaken is connected to through town twinning

Culture and sights

theatre

- Burghofbühne Dinslaken

- Burgtheater Dinslaken

- Filou theater

Museums

- Voswinckelshof City History Museum

- Motor Archive Krulik

- Mill museum Hiesfeld

Buildings

The remains of the medieval Dinslaken Castle are part of the current town hall. A family named after the castle was first mentioned in a document in 1163. Next to the castle is the Burgtheater , the city's open-air stage. The Bollwerkskathe is a former blacksmith's shop that comes from the Hiesfeld district and was placed in front of a preserved piece of the medieval city wall made of field-fire bricks. This was renovated in 2007 and saved from deterioration. The city wall was originally 2.50 m to 3 m high. From the old city fortifications only the knight's gate and some wall sections along the Rotbach remained. (Opposite the Bollwerkskathe is a cart from the Lohberg / Osterfeld colliery, in which hard coal was mined under Dinslaken.)

The Voswinckelshof goes back to the 13th century. It was one of four noble seats in the city. In 1527 the owners signed a contract with the city of Dinslaken that allowed them to demolish a piece of the city wall on their property in order to erect a new building outside the course of the city wall. The current building, which was probably built at the end of the 18th century, stands on the foundations of a previous building that was built in 1527. Before the First World War, the Voswinckelshof was a children's rest home. Since 1955 the city-historical "Museum Voswinckelshof" has been housed there. It was reopened in 1999 after extensive building renovation and has since offered a diverse program of exhibitions and events.

The St. Vincentius Church is one of the two town churches in the historic old town, it was founded in 1273 as "Capella Curata" and only raised to parish church in 1436; that was how long the Dinslaken Christians belonged to the Hiesfeld mother church, which later switched to the Protestant faith. The church was built as an early Gothic hall church, made of bricks, there were only striking external changes to the tower in the west of the church, which received new tower domes several times. In the last days of the war there was an artillery hit on the tower, which broke in 14 days later and buried half of the church under itself. In 1951 the west end was rebuilt, adding a transept with a west choir, and a new bell tower in the north-west of the church. This unusual combination makes this church almost unique in its construction. Since 2007 the bells of the abandoned Christ Church have been ringing in the tower of the St. Vincentius Church. The church is open to the public at certain times of the day.

The Evangelical City Church has been preserved from 1720. Originally founded in 1653, it burned down in 1717, was rebuilt and inaugurated in 1723. In 2000 the church was fundamentally restored (danger of collapse due to damage to the foundation and the tower construction) and has since been open to all believers and interested parties. Since 2007 it has been a place of worship for the city center and the Christ Church district after the Christ Church was demolished.

The two headframes of the former Lohberg colliery testify to the earlier importance of hard coal mining for Dinslaken. The scaffolding above shaft 1 from the time the colliery was founded (1910) is a German strut frame. The scaffolding of shaft 2 was designed by the architect Fritz Schupp in 1955/56 . It is a unique mixed construction of a tower headframe and a double jack. Today the 70.5 meter high construction is the landmark and landmark of the Lohberg district.

Also noteworthy buildings are the windmill and the water mill in the district of Hiesfeld.

Nature and leisure

- Tendering lakes near the northwestern district of Bruch, here in particular the lido . However, according to the local boundaries, none of the lakes actually belong to Dinslaken.

- Rotbach-Route cycle path on the Rotbach with Rotbachsee and Emscher estuary

- the city center offers numerous shopping opportunities

Sports

- Citizen shooting club Dinslaken 1461 , oldest shooting club in town

- Trabrennbahn (the only half-mile track in Germany)

- Ice rink Dinslaken (home of the Dinslaken Kobras , formerly DEC and DEV)

- Dorotheen Kampfbahn (home of VfB Lohberg )

- Stadion am Rotbachsee (home of TV Jahn Hiesfeld )

- District sports facility on Voerder Straße (home of SuS 09 Dinslaken )

- Square at the Volkspark (home of SC Wacker Dinslaken)

- Airfield Dinslaken / Schwarze Heide (home of the Luftsportverein Dinslaken e.V. )

- District sports facility Oberlohberg (home of the SGP Oberlohberg)

- Apartment forest with different, signposted running routes

- With the rise of the 1st men's team of the Dinslaken chess club in 1923 e. V. In the 2014/2015 season, the city will provide a representative in the 2nd Bundesliga for the first time .

Economy and Infrastructure

Mining

From 1914 to 2005 the coal mine Zeche Lohberg (from 1989 Lohberg-Osterfeld mine ) was active in the Dinslaken district of Lohberg . At times it was the city's largest employer with over 5,000 employees.

retail trade

In July 2012 there were around 400 retail outlets with a total sales area of around 122,000 square meters throughout the city. There are currently (as of September 2014) 165 providers in Dinslaken's city center, including retail stores such as Betty Barclay , Jack Wolfskin , Brille Eckmann, Küchen Penzel and Eine-Welt-Laden Dinslaken. A retail report by the Society for Market and Sales Research (GMA) from April 2008 described the need to improve the supply situation in Dinslaken after the abandonment of a full-range supplier and several local suppliers in the city center and stated that "a possible revitalization of this area would meet the goals of retail and the center concept (the overriding goal of a comprehensive, near-residential basic supply as possible). ”With the Neutor Galerie Dinslaken on the area of the former Hertie department store , a further 16,000 m² was added in autumn 2014.

traffic

The tariff of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr applies to all local public transport (ÖPNV) and the NRW tariff applies to all tariff areas . There are several bus lines and bus stops all over Dinslaken, a train station in the city center and the tram line 903, which goes in the direction of Duisburg Hbf. And further. The light rail line has only four stops in Dinslaken, all of which are above ground - so it is a tram in Dinslaken.

Rail transport

The Dinslaken Train Station is located 600 m northeast of the city center at the Oberhausen-Arnhem railway .

In the SPNV , the Rhein-Express ( RE 5 ), the Rhein-IJssel-Express ( RE 19 ) and the Wupper-Lippe-Express ( RE 49 ) operate at the station . The tariff of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr (VRR) applies to all public transport and the NRW tariff applies to all tariff areas .

The city is currently planning to buy the station, renovate it and then rent it to the railway. There are also plans by the city to renovate the station forecourt.

There are no other train stations or stops in the city. Not even in the Hiesfeld district, although this is home to a good quarter of all Dinslaken residents and is also directly on the Oberhausen – Arnhem railway line.

Bus and tram transport

In road passenger transport run

- the express bus line SB 3 to Wesel to link with the neighboring municipality of Hünxe ,

- the tram line 903 of the Duisburger Verkehrsgesellschaft , which usually runs every 15 minutes from Dinslaken via Walsum , Hamborn , Meiderich , Duisburg Hauptbahnhof , Stadtmitte and Hochfeld to Hüttenheim , and

- eight further regional and city bus routes operated by NIAG , which is part of the Rhenus-Veniro group , for spatial and inner-city development.

Streets

Dinslaken is connected to the federal motorways 3 ( E35) and 59 as well as the federal highway 8 , all three of which lead through the city of Dinslaken. The federal freeway 3 also reaches the federal freeways 2 and 516 at the nearby Oberhausen interchange . The A59 begins in Dinslaken at the Dinslaken-West junction and has no connection to the federal highway 3 in the city of Dinslaken, but this connection is guaranteed by the federal highway 8.

education

The city of Dinslaken has ten primary schools, three grammar schools, a secondary school, a comprehensive school, a vocational college spread over two locations, a special needs school and the Dinslaken Waldorf school. A grammar school and a secondary school are combined in the Gustav-Heinemann-Schulzentrum (GHZ) in Dinslaken-Hiesfeld, with the secondary school moving in summer 2020 and the "Gymnasium im Gustav-Heinemann-Schulzentrum" (GHZ) building with the new building "Comprehensive School Hiesfeld" divides and is renamed Gustav-Heinemann-Gymnasium (GHG). The other two grammar schools are the Otto Hahn grammar school and the Theodor Heuss grammar school . Comprehensive school instruction is given at the Ernst Barlach Comprehensive School .

Personalities

sons and daughters of the town

Personalities who were born in Dinslaken:

- Heinrich Douvermann (around 1480 – around 1543), the picture carver from the Lower Rhine, created, among other things, the Altar of Mary in the collegiate church in Kleve, the Altar of Seven Pains in the parish church of St. Nicolai in Kalkar and the Altar of Mary in the Xanten Cathedral

- Johann Christian Jakob Schneider (1767–1837), doctor in Krefeld

- Friedrich Wilhelm von Winterfeldt (1830-1893), German landscape painter

- Friedrich Althoff (1839–1908), Prussian cultural politician

- Dietrich Barfurth (1849–1927), physician and anatomist, rector of the University of Rostock

- Wilhelm Lantermann (1899–1973), politician (SPD), Mayor of Dinslaken

- Heinrich Bernds (1901 – lost 1945), Reformed theologian and economist

- Bernhard Roßhoff (1908–1986), district and community director in Sonsbeck, member of the state parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia

- Mathilde Muthig (1909–1996), NS doctor at the Kalmenhof

- August Dickmann (1910–1939), first conscientious objector to be executed under the National Socialist dictatorship in Germany during World War II

- Antonín Sochor (1914–1950), Major in the Czechoslovak Army, Hero of the Soviet Union

- Maria Sander-Domagala (1924–1999), track and field athlete and Olympic medalist

- Reimar Gilsenbach (1925–2001), writer, environmental and human rights activist

- Otto Wesendonck (* 1939), sculptor

- Christel Neudeck (* 1942), co-founder of Cap Anamur

- Alfred Grimm (* 1943), object artist, painter and draftsman

- Pidder Auberger (1946–2012), visual artist and photographer

- Udo Heinrich (* 1947), painter

- Bernd Wegener (* 1947), entrepreneur and pharmaceutical lobbyist

- Klaus Kracht (* 1948), professor of Japanese language and culture at the Humboldt University in Berlin

- Herbert Dittgen (1956–2007), Professor of Political Science at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz

- Frank Saborowski (* 1958), soccer player (including MSV Duisburg, Bayer 04 Leverkusen, VfL Bochum)

- Peter Loontiens (* 1958), soccer player, 1985 DFB Cup winner with Bayer Uerdingen

- Thomas Hoeren (* 1961), professor for media law and civil law at the Westphalian Wilhelms University in Münster

- Jörn Vanhöfen (* 1961), photographer

- Armin Willingmann (* 1963), professor of civil and commercial law and since 2003 rector of the Harz University of Applied Sciences

- Wolfgang de Beer (* 1964), soccer goalkeeper at MSV Duisburg and Borussia Dortmund, today goalkeeping coach at Borussia Dortmund

- Andreas Püttmann (* 1964), political scientist, journalist and publicist

- Wolfgang Strengmann-Kuhn (* 1964), economist and politician (Alliance 90 / The Greens)

- Thomas Wittke (* 1964), comic artist and illustrator, editor of the comic anthology Panik Elektro

- Renate Lieckfeldt (1965–2013), pharmacist

- Ibrahim Yetim (* 1965), politician (SPD)

- Adnan G. Köse (* 1966), director and screenwriter

- Katrin Himmler (* 1967), author

- Ralf Kelleners (* 1968), racing car driver

- Michael Wendler (* 1972), composer and pop singer

- Thorsten Passfeld (* 1975), painter, sculptor, stage designer, animator, author and musician

- Stefanie Lohaus (* 1978), journalist and cultural scientist

- Jessica Kessler (* 1980), figure skater and actress

- Lena Amende (* 1982), actress

- Benjamin Musga (* 1982), ice hockey player

- Serkan Çalık (* 1986), football player

- Paula Kalenberg (* 1986), actress

- Timm Golley (* 1991), soccer player

- Maika Küster (* ≈1993), jazz and improvisation musician

- Dennis Jan Szczesny (* 1993), handball player

- Linda Dallmann (* 1994), soccer player

- Philipp Köhn (* 1998), soccer goalkeeper

- Thorsten "IPPI" Ippendorf (* 1971), film producer and actor

Personalities who worked in Dinslaken without being born there

- Heinrich Grütering (1834–1901), district judge in Dinslaken, member of the Reichstag

- Jeanette Wolff (1888–1976), politician and deputy chairwoman of the Central Council of Jews in Germany

- Willi Dittgen (1912–1997), head of the cultural office, head of adult education center and local researcher

- Euthymia Üffing (Sr. Euthymia) (1914–1955), religious sister, beatified in 2001

- Walter Hellmich (* 1944), football functionary and building contractor

- Ulrich Deppendorf (* 1950), journalist and moderator

- Udo Di Fabio (* 1954), judge at the Federal Constitutional Court

- Andreas Deja (* 1957), draftsman and animator for Walt Disney Pictures

- Norbert Elgert (* 1957), former soccer player and current coach of the youth department at FC Schalke 04

- Henning Heske (* 1960), poet and essayist

Fictional personalities

- Uschi Blum , a fictional character by the comedian Hape Kerkeling , who is said to have grown up in Dinslaken

- Freifrau von Kö , a fictional figure of the travesty artist and city guide Andreas Patermann, who is also said to come from Dinslaken

literature

- Lothar Herbst (Ed.): Dinslaken am Niederrhein - reports and city guides about Dinslaken am Niederrhein. BoD-Verlag, 2017, ISBN 978-3-7431-6301-0 .

- Friedhelm van Laak (ed.): Power and powerlessness - reports from Dinslaken on the Lower Rhine. 2006.

- Gisela Marzin (Ed.): Dinslaken in old views. European Library, Zaltbommel (NL) 1988, ISBN 90-288-4728-6 .

- Gisela Marzin: Dinslaken - eventful times. The 50s. Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 1996, ISBN 3-86134-302-9 .

- Gisela Marzin: Dinslaken as it used to be. Wartberg-Verlag, Gudensberg-Gleichen 2002, ISBN 3-8313-1030-0 .

- Anne Prior: "Where the Jews stayed is (...) not known." November pogrom in Dinslaken 1938 and the deportation of Dinslaken Jews 1941–1944. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2010, ISBN 978-3-8375-0341-8 .

- Rudolf Stampfuß , Anneliese Triller : History of the City of Dinslaken 1273–1973 (= contributions to the history and folklore of the Dinslaken district on the Lower Rhine. Volume 10). Schmidt-Degener, Neustadt a. d. Aisch 1973, DNB 740024221 .

- Kurt Tohermes, Jürgen Grafen: Life and fall of the synagogue community Dinslaken (= Dinslaken contributions to history and folklore. Volume 17). Edited by the Association for Home Care "Land Dinslaken". Dinslaken 1988, DNB 890736324 .

- Annelise Triller (arrangement): City book of Dinslaken. Documents on the history of the city from 1273 to the end of the 17th century (= contributions to the history of the Dinslaken district on the Lower Rhine. 2). Schmidt-Degener, Neustadt a. d. Aisch 1959.

Web links

- Website of the city of Dinslaken

- Website and city guide Dinslaken by web designer, author and photographer Lothar Herbst

- Website town twinning association Dinslaken with AGEN and ARAD

- Website of the Heimatverein Dinslaken e. V.

- Historical data from Dinslaken at GenWiki

Individual evidence

- ↑ Population of the municipalities of North Rhine-Westphalia on December 31, 2019 - update of the population based on the census of May 9, 2011. State Office for Information and Technology North Rhine-Westphalia (IT.NRW), accessed on June 17, 2020 . ( Help on this )

- ^ City of Dinslaken | Dinslaken in numbers. Retrieved on August 21, 2018 (source: Kommunales Rechenzentrum Niederrhein (KRZN), calculations by the city of Dinslaken).

- ↑ Erich Wisplinghoff : Explanations to: Johann Bucker: Map of the Rhine from Duisburg to Arnheim from the year 1713. [Text part]. Edited by the North Rhine-Westphalian State Archives, Düsseldorf 1984, pp. 5–10, DNB 209850728 .

- ^ Anne Prior: "Where the Jews stayed is (...) not known." November pogrom in Dinslaken 1938 and the deportation of Dinslaken Jews 1941–1944 . Klartext Verlag, Essen 2010, pp. 22–33.

- ↑ Out of sight, to war. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . No. 173, July 29, 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ From the German province to the Syrian war. In Deutsche Welle, April 23, 2019. https://www.dw.com/de/aus-der-deutschen-provinz-in-den-syrien-krieg/a-48215834-0

- ↑ a b Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality register for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 292 .

- ^ Rolf Nagel: Rheinisches Wappenbuch. Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-7927-0816-7 , p. 103.

- ↑ Logo and coat of arms of Dinslaken. In: dinslaken.de. Retrieved September 20, 2013 .

- ^ Georg Cornelissen : Dialects in the Rhineland. (No longer available online.) In: rheinische-landeskunde.lvr.de. Institute for Cultural Studies and Regional History, archived from the original on May 3, 2012 ; accessed on April 18, 2018 .

- ^ Regiolekt in the Rhineland. (No longer available online.) In: rheinische-landeskunde.lvr.de. Institute for Cultural Studies and Regional History, archived from the original on June 20, 2012 ; accessed on April 18, 2018 .

- ^ City of Dinslaken Religion , 2011 census

- ^ Dinslaken in numbers. In: dinslaken.de, accessed on August 15, 2020.

- ^ Dinslaken in numbers. In: dinslaken.de, accessed on July 8, 2019.

- ↑ State Returning Officer NRW: Municipal elections 2014, final result for Dinslaken

- ↑ Municipal data center Niederrhein: Council election May 25, 2014 Election to the Council of the City of Dinslaken - distribution of seats

- ↑ Rudolf Stampfuß, Annelise Triller: History of the City of Dinslaken 1273–1973. 1973, pp. 619-621.

- ^ Website Dinslaken, Alte Freunde - diverse contacts

- ^ Philipp Völker, Stefan Kruse: Draft for the retail and center concept city of Dinslaken. (PDF 3.9 MB) In: Innenstadt-dinslaken.de. Junker + Kruse, November 20, 2012, p. 32 , archived from the original on October 30, 2014 ; Retrieved on April 18, 2018 (on behalf of the city of Dinslaken).

- ↑ Randolf Vastmans: Citizens' decision on the renovation of the station forecourt on June 10, 2018. In: lokalkompass.de, May 8, 2018, accessed on February 18, 2019.