Mining in the Sauerland

The mining in the Sauerland (the former here largely focused Cologne Sauerland ) on iron and non-ferrous metals was one of the foundations of the pre-industrial economic development of this region to partially 20th to the early century. The first beginnings can be traced back to antiquity. During this period, as in the Middle Ages, lead and copper mining was of great importance. In the early modern era, iron mining came to the fore. Mining flourished particularly during the 16th century. After that the development was changeable. Against the background of industrial development, mining experienced a renewed temporary boom in the 19th century. At the end of the century, iron ore mining was largely discontinued, while other areas were partly operated well into the 20th century. Today some visitor mines remind of the mining and industrial past of the region. In the past few years, research into the history of mining into the “forgotten area” has also got underway.

Natural conditions

The Sauerland as part of the Rhenish Slate Mountains has various non-ferrous metals such as lead , zinc and copper that are worth mining in various compression zones . These include the areas around Brilon , Marsberg , Ramsbeck and Olpe . Brown and red iron ore , on the other hand, occur almost throughout the region. In addition to the ore, the numerous rivers and streams offer good conditions for the use of hydropower. The wood of the forests, processed into charcoal, can be used for smelting .

Early mining

Ancient mining

The earliest evidence of mining in the Sauerland is for the early Roman Empire ; in pre-Roman times no mining has been reliably proven.

A clear find deposit from the pre-Roman Iron Age in various caves as well as the construction of at least one rampart castle in the Warsteiner area ( Bilsteinhöhle , Eppenloch, Hohler Stein , rampart castle on the Schafsköppen near Kallenhardt ) as well as in other areas of the Sauerland proves a settlement of the rather inhospitable mountainous country, too associated with the relative wealth of iron ore. However, there are still no reliable traces of Iron Age mining or Iron Age smelting. The dating of the kilns excavated in the Lörmeckal in the 1930s is unclear, the Iron Age dating published at the time must be regarded as uncertain.

More recent research now assumes that lead was extracted in the area of Brilon during the Roman rule in Germania. Whether the deposits were owned by the emperor, the mining itself was leased to entrepreneurs and whether the plumbum Germanicum was exported to the Mediterranean region is currently the subject of discussion between epigraphers and mining archaeologists. It is also unclear whether the Kneblinghausen Roman camp was built under Roman direction to protect potential businesses. As far as Sardinia there are numerous finds of lead ingots from the area around Brilon from Roman times. It is not yet clear, but it cannot be ruled out that copper was also mined around the future Marsberg.

Mining in the Middle Ages

Ore mining can be proven archaeologically until at least the early Middle Ages. A saltworks from the 6th / 7th centuries was built near Soest . Excavated in the 16th century. The remains of lead pans for salt boiling were found . This material may also have come from near Brilon. There is written evidence of lead extraction in this area for 1103.

Marsberg copper ore was mined as early as the 8th century and processed in the villa Twesine near the Diemel, east of Marsberg. 36 ovens and roasting pits have been found there, which can be dated to between 700 and 750 with the help of ceramic finds. Wilfried Reininghaus suspects that the Carolingian conquest of the Eresburg had strategic reasons as well as securing the ore deposits there.

In the Carolingian period, settlement began to flourish, which advanced into the highlands into the 14th century, as well as mining. It is unclear to what extent the Hungarian invasions had an impact. It is certain that a renewed upswing took place in the Ottonian and Salian times : for the period between 999 and 1155 there are numerous mining and smelting remains in the sea of rocks near Hemer . The smelting took place in racing fire furnaces . In Ramsbeck, radiocarbon dates show underground mining on the Bastenberg around the year 1000. The importance of the mining industry increased until around 1350.

The monasteries played a major role in the upswing. The Bredelar Monastery has been active in the mining industry since it was founded in 1196 and played a major role in the expansion of the iron mines in the Diemel-Hoppecke area. Copper and iron were extracted in the villages of Giershagen , Messinghausen and Rösenbeck , which belong to the monastery . The basic material equipment of the Grafschaft monastery included, in particular, properties that were located in mining areas around Hemer and Attendorn. The women's monastery in Oelinghausen was also at least temporarily active in the mining sector.

Castles of the high nobility were located near iron ore deposits. This is proven by the Rüdenburg near Arnsberg in the immediate vicinity of the Eisenberg, where Pingenfelder was found.

The development of cities was also closely related to mining. Horhusen (today Niedermarsberg) gained importance as a market settlement as early as the 10th century, not least as a result of the nearby copper production. Goods made of copper and iron were produced and sold in the village. The rise of Attendorn to an important city in the Cologne-Westphalia region was also due to the nearby, easily accessible ore deposits of the Ebbe Mountains. The decision for the location of the town of Eversberg, founded in 1242, was influenced by the local ore deposits. Pinging has also been found nearby. The same applies to other cities and freedoms founded by the Counts of Arnsberg or the Archbishops in the 12th or 13th century, which were often located in local mountain areas and brought the mining products into the trade. Brilon became a center of non-ferrous metal extraction and was economically closely linked to the city of Soest.

There were conflicts over ownership of the pits in 1273 when the Lords of Padberg filed their claims. The dispute was settled through the mediation of the cities of Marsberg and Korbach . The smelting of near-surface iron ore using racing kilns is likely to have been widespread throughout the region at this time. The manufacture of weapons and armor was of considerable economic importance both in the county of Mark and in the area of the Duchy of Westphalia. Iserlohn and Marsberg were next to Soest and Dortmund am Hellweg centers of arms production.

Copper mining was increasingly concentrated in the area around Marsberg, while at Brilon mainly calamine and lead were extracted. In the Plettenberg area , copper mining is said to have been in the Bärenberger adit since 1338 . A documentary mention of an ironworks in Endorf from 1348 suggests mining activities. There and in Bönkhausen there was also lead mining since the 14th century.

In the Bilstein valley near Warstein (a few hundred meters from the Bilstein cave), ironworks sites were excavated around 1900, which may be dated to the Middle Ages. No written records are currently known about these excavations, not even the exact location of the ovens can be determined. In autumn 2006 a new racing kiln was found in this area; further findings indicate iron production. In this context, a mining district only 150 meters above the furnace site is interesting. It seems reasonable to assume a direct connection here, but there are still no datable finds. This mining area (in the "Gössel" forest corridor, used as a shooting range in the 19th century, today partially lynx enclosure in the Warsteiner Wildlife Park) has a size of at least 1.5 hectares and makes a multi-period impression. A mining site, the "Winterkuhle", which has now been filled in, is located nearby. This already appears in a document from 1489, which speaks for the medieval era of mining and iron production in the Bilstein valley. Field names in documents from the late Middle Ages and the early modern period also indicate a “copper pit” and a “lead pit”, which cannot be precisely located. The "Kupferkuhle" area has been largely destroyed by modern limestone mining, the "Bleikuhle", located in the "Dahlborn" area of the document, has not yet been found in the area. It is possible that mining in the Oberhagen area dates back to the late Middle Ages. A "smedewerk" (ironworks with attached hammer) mentioned in 1364 may have been located in the area of the later ironworks at the foot of the Oberhagens.

It is not entirely clear whether mining in the Sauerland was more severely affected by the economic crisis in the late Middle Ages. There is evidence that iron mining has continued. In the Brandenburg Sauerland, new techniques came up with the raft ovens and fresh fires . They were adopted in the area of the later districts of Olpe and Arnsberg , while the older technology continued to prevail in the eastern area. The fact that some mining locations such as Blankenrode or the first settlement of lead washing fell into desolation speaks for a certain crisis . After 1470 the coal and steel industry recovered like everywhere in Central European mountain areas, in contrast to the large mining centers, in which mining flourished again from 1475, there was no comparable upswing in the Sauerland.

From the end of the 14th century, efforts by the Archbishop of Cologne to claim the sovereign's mountain shelf recorded in the Golden Bull of 1356 can be proven . This can be seen from the granting of mining rights near Rüthem around 1390. An intensified dispute emerges in 1482 when the von Neheim family complained about the withdrawal of the tithe on lead from the Stockum court. Land law still played a role compared to mining law in the 16th century.

Early modern age

Mining in the 16th century

In the 16th century the structure of the old districts around Brilon and Marsberg changed. Instead of lead and copper, iron smelting and processing came to the fore. The merchants of both cities invested in iron smelting and processing into rod iron in the eastern Sauerland as far as Waldeck . For example, there were numerous water-powered hammer mills on the Diemel , Hoppecke and Itter rivers . The processing of metals into furnaces, bells or guns made of cast iron also became of considerable importance. From Beverungen , the closest port on the Weser, several hundred thousand pounds of iron and hardware were sold every year to Bremen . There were conflicts between the citizens of the cities, the Bredelar monastery and aristocratic families such as those of Padberg over scarce resources, such as wood. The ore raw material in this part of the region came mainly from the Briloner Eisenberg and the Assinghauser Grund . Not least because of its wealth of raw materials, the Assinghauser Grund was controversial between Waldeck and the Electoral Cologne Duchy of Westphalia. Mining experienced a significant boom around Siedlinghausen after 1560. In 1596 there were 16 mines and 23 huts in the Brilon Gogericht alone .

In addition, the Lenne valley with its tributaries was a center of the coal and steel industry with numerous hammer and steel works. In addition to local mining, these plants obtained part of the raw materials from the neighboring Siegerland ore mining . While bourgeois entrepreneurial families were the driving force around Brilon and Marsberg, the nobility played an important role on the Lenne at that time. The von Fürstenberg family in particular was heavily involved in the mining sector. Mining on the Rhonard near Olpe was controlled by the Cologne Electors and the Counts of Siegen from 1550 .

Lead and copper production probably declined not least because the ores near the surface were largely mined. The promotion experienced a short-term upswing under Elector Gebhard von Mansfeld . He brought in external experts and investors. (Partly) silver-bearing lead ore deposits near Endorf , Silbach or Ramsbeck were exploited . Copper mining also took place on the Bastenberg in Ramsbeck and in Hagen , on the Kupferberg near Meinkenbracht and, above all, in the Rhonard near Olpe . Silbach was raised to mountain freedom at the time of Elector Gebhard von Mansfeld , Endorf at the end of the 16th century under Elector Ernst von Bayern . The electoral miner had his seat in Endorf at that time. The supra-regional importance is supported by the fact that Augsburg citizens invested as trades in lead, copper and vitriol near Rüthen after 1560 .

Mining in the 17th and 18th centuries

The good sales situation for most of the mines lasted until the Thirty Years' War . The development during the Thirty Years' War was partly contradictory. At first, mining and processing companies benefited from the demand for war material. In 1620 Dutch merchants invested in mining and smelting in the Sauerland. A hut was built near Stadtberge (later called Marsberg ), which mainly specialized in cannons and cannonballs. In the further course of the war, armaments were exported, as in 1633 to Amsterdam. In 1643 iron from the Sauerland was still a sought-after commodity for merchants from Bremen. The war had a negative impact on the population through the destruction of the agricultural livelihoods. Overall, the region suffered from the fact that it was only inadequately able to compensate for these consequences of the war.

In the post-war period until the end of the old empire the development was changeable. Again and again there was a cessation of mining and processing in the individual areas. On the other hand, the Briloner Eisenberg began to be mined for ore located deeper with the help of unionized heritage tunnels. The yield was sufficient to operate a number of iron and steel mills. But the expansion was severely hindered by technical problems in some areas around Giershagen. In particular, the dewatering was not brought under control. At times, the smelting works and hammer mills around Marsberg were dependent on ore imports from Waldeck. In Assinghauser Grund and around Medebach, iron production lost its importance. Some of the formerly employed in mining and in hammer mills were dependent on seasonal work. Up to the 19th century they manufactured nails in the home industry in Bruchhausen and Silbach , for example , which were sold by traveling traders in the upper Sauerland. The number of nail smiths was very high at 500 in 1850.

Overall, the focus shifted to the Lenneraum and the Röhr and Hönne valleys . In the first half of the 18th century, iron mining revived in the area of Balve , Sundern and the areas around Drolshagen , Attendorn and Olpe in the Biggetal. In this area the bourgeois entrepreneurs played less of a role than the nobility to a large extent. The economic upswing in the Sauerland region of the Mark, in particular the production of finished goods in Altena, Iserlohn and Lüdenscheid had a significant influence on this development. Quite a few Brandenburg merchants and entrepreneurs invested in the region. In the northwest of the region there was a strong economic integration with the Brandenburg area. In addition, the iron merchants from Olpe developed stronger entrepreneurial activities and acquired hammer works on the upper Lenne and around Kirchhundem. The Wendener Hütte, which was founded around 1720, and other smelters increased the demand for ore. In the Sauerland in Cologne, older mines were reopened and new mining areas opened up. However, the demand clearly exceeded the output, so that the iron and steel works on the Lenne were heavily dependent on raw material imports from the Siegerland.

There has been a probably continuous mining and smelting operation in the Warstein area since the late 16th century. Here played Matthias Gerhard von Hoesch and his followers an important role. They owned an ironworks in which they processed ores from Suttrop and other areas as well as charcoal from the electoral forests. A first reliable indication of underground mining can be found on a map from 1630, where a tunnel is entered in the “ Oberhagen ” area , in the immediate vicinity of a drawn iron hammer and an ironworks . In the Oberhagen area, numerous traces of mining can still be found today: Pingen, collapsed mine structures, collapsed tunnel mouth areas, heaps, traffic routes. Related mining traces in Oberhagen can be found on an area of around 3 hectares. Some areas of the “Rome” pit are still accessible underground today, including a drainage tunnel at least 200 meters long. Mining has also been practiced in this area for several centuries. It currently appears that there was a relative upswing in the Warsteiner coal and steel industry up to the middle of the Thirty Years War, which then ended. It was not until the early 18th century that mining and iron processing were resumed on a larger scale in Warstein (concession of an ironworks by Archbishop Clemens August in 1739).

Just like iron ore mining, the mining of non-ferrous metals also experienced periods of boom and phases of crisis between 1648 and 1815. Overall, this lagged behind the development in the High Middle Ages. Copper mining at Rhonard declined sharply at the beginning of the 17th century. It was only operated very profitably from the 1680s when it was owned by the von Brabeck family . Copper mining also flourished in Silberg in the 18th century, and the Kassel brass yard was the owner .

Copper mining in the Silbach was of a certain importance between 1690 and 1765, after which it was only continued to a small extent. Mining in Ramsbeck was initially under the control of the electors before it gradually passed into the possession of the nobility and bourgeoisie. The at times high expectations were hardly fulfilled in the 18th century. On the other hand, there was an upswing in Marsberg copper mining from around 1690. In the process, old deposits were opened up again and speculations were made in the area for new deposits. Copper was mined and smelted in Marsberg itself. Merchants from Hessen and Johann Theodor Möller from Warstein played an important role in the development. Mining for antimony began on a modest scale in the Caspari colliery near Arnsberg towards the end of the 18th century .

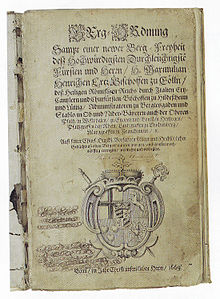

Mining policy and mining administration

Land and mining law stood side by side until the 16th century . The elector of Cologne made claims from the lordly Bergregal in the 14th and 15th centuries . However, it was not until the 16th century that he regulated mining law more comprehensively by issuing mining regulations and establishing his own mining administration.

In 1533 the first mountain order was issued, which was followed by several until 1559. These were mainly concerned with the tunnel mining in the Sauerland from around 1530 and based on Saxon mining law. The sovereigns were interested in expanding the mining sector. In 1559 they granted the trades of the Assinghauser Grund extensive rights in mining and metallurgy, raised Silbach and Endorf to mountain freedom and introduced a mining administration. External experts came as mountain administrators and external capital was invested. In 1605 the archbishop even waived the mountain tithe for 18 years in order to promote expansion in the mining sector. The expectations cherished in the survey on mountain freedoms were not fulfilled, in both places the importance of mining declined in the 17th century. Endorf lost the mining authority and no longer appeared as freedom in the 18th century.

| year | title | Decree by | comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1533 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Elector Hermann von Wied | |

| 1534 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Elector Hermann von Wied | |

| 1549 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Elector Adolf III. from Schaumburg | |

| 1557 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Elector Anton von Schaumburg | |

| 1559 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Elector Gebhard von Mansfeld | |

| 1669 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Elector Maximilian Heinrich of Bavaria |

After the Thirty Years' War, the archbishop tried to improve the mining industry and the economy in the duchy. The measures to strengthen the domestic economy had mercantilist features. However, due to the mercantilist policies of other states, the situation in the Duchy of Westphalia remained bad. During this time the last electoral mountain regulations (1669) were issued. Because of the current sales problems in the foreign iron trade, further processing took up a large part of it.

The seat of the Westphalian Mining Authority gradually shifted from Endorf to Brilon after the Thirty Years War. It was headed by a mining captain, had to ensure that the mining tithe was paid to the government treasury, and was responsible for the granting of mutually beneficial rights , mortgages and jurisdiction in the entire area of mining, metallurgy and hammering. After 1650, Olpe developed its own sub-mining authority. Although Brilon retained sovereignty on paper, the Olper Mining Authority acted effectively autonomously. Both offices were subordinate to the court chamber founded in Bonn in 1692. This succeeded better than the mining authorities in asserting themselves against the local nobility.

The influence of the mining administration declined more and more in favor of the coal and steel owners after 1680, which was also due to the fact that no experts were brought into the mining authorities. Trades like sovereign were more interested in the annual income than in sustainable development. Iron was imported to utilize the domestic smelters and hammers. The punitive tariffs on imported pig iron were lifted again after negotiations between the knighthood and the cathedral chapter in 1711. Coal, which was needed for domestic production, was also in demand in neighboring territories. Export was banned in 1679, but this did not seriously prevent noble forest owners from exporting. After the Seven Years' War there were considerations to force miners from every location, but this was not realized. In order to be independent of imports and to cover the powder needs in mining, the sovereign promoted the establishment of a powder mill in Hellern near Meschede in the 1780s .

At the end of the 18th century, Franz Wilhelm von Spiegel , who was Landdrost and later President of the Court Chamber, tried to reform the coal and steel industry. He also planned to set up a mining academy in Brilon. He denounced the lack of plan, short-sightedness, ignorance and selfishness of private companies aiming for quick profit, but could not achieve much in his short term in office.

Organization and supporting forces

The nobility, monasteries and municipal trades appeared as mining entrepreneurs; there were seldom electoral private businesses. The Bredelar Monastery and the Grafschaft Monastery should be mentioned as monasteries , which were already active in the mining industry in the High Middle Ages. Bredelar Monastery owned a large number of mine parts until it was closed.

The nobility played an important role in the development of the mining industry. The noble families either participated in trade unions or operated their own mines on their property. These noble entrepreneurs included the houses of Fürstenberg (from 1560 in the Olpe district, until 1780 also in Ramsbeck), von Wrede ( Julianenhütte near Amecke), von Landsberg-Velen ( Luisenhütte near Balve ) but also the von Dücker families , the Spiegel zum Dessenberg on their property in Canstein and that of Plettenberg . The von Brabeck family was able to expand their company nationwide and also operated mines in the Harz Mountains and Siegerland . It is estimated that between 1660 and 1803 around a quarter of all aristocratic families eligible for parliament owned mines or other assembly-related businesses. Between 1720 and 1750 in particular, the nobility intensified their involvement in the mining sector. His attempt, similar to that in the vertically organized corporations of the 19th and 20th centuries, is remarkable. Century to combine all processing steps from ore mining to smelting, the manufacture of semi-finished products to finished products.

In the early modern period, mining-based approaches of a Sauerland economic bourgeoisie developed, especially in the areas of Brilon, Marsberg, Attendorn and Olpe. Merchants working in the coal and steel sector have been documented since the 15th century at the latest. In many cases, unions under mining law operated the mines. Wealthy landowners and townspeople invested in these societies. For some, the mining involvement was already taking on a modern appearance; the Ulrich entrepreneurial family, for example, owned large shares of the pits in East Sauerland and a whole series of smelters and hammers for further processing. In other parts of the region, too, the pits were used to supply raw materials to nearby iron and steel works. In the Sundern area, for example, the Endorfer Hütte belonged to the Lentze family. Often pits and processing companies were connected. The term Reidemeister developed for such entrepreneurs since the 16th century . Some of these had extensive business relationships; Reidemeister from Marsberg did business with partners in the Netherlands around 1600. In today's Olpe district, the focus has been transferred from Attendorn to entrepreneurs from Olpe since around 1550. Trades in rural areas mostly belonged to the village upper classes.

Quarries up to the 18th century

In addition to ore mining, there were also commercially used stone deposits in the Duchy of Westphalia, some of which began to be mined in the Middle Ages. Deliveries of Rüthener green sandstone to churches and monasteries in the Münsterland can be traced back to the 14th century . After the Thirty Years War, this building material attracted craftsmen from all over the German-speaking area. Early slate mining areas were Antfeld and Hallenberg. According to local tradition, slate mining in Antfeld is said to have started in the 16th century. The mining was carried out by the noble owners of the Antfeld family , who fought against peasant competition from Nuttlar in 1727. Slate from Hallenberg was used in 1578 for the new construction of Arnsberg Castle . Millstones and stones for the construction of blast furnaces have been supplied from quarries near Kallenhardt since the 16th century at the latest.

Mining in the 19th and 20th centuries

Iron ore mining and smelting decline in the 19th century

Due to the comparatively poor sources, no precise statements can be made about the importance of the economy and mining in Westphalia in the Electorate of Cologne. However, it will have been comparable to the importance of neighboring regions. The disparaging assessment of the region by Prussian officials and military around 1800 is viewed as polemical.

After Prussia took over the Duchy of Westphalia in 1815, however, there was no improvement. The deposits were still productive, but the production techniques could hardly compete with those in the Sauerland and Ruhr area in the Marks, which, in contrast to the Sauerland, were no longer based on charcoal but on hard coal, whose transport to the Sauerland was unprofitable. In addition - as in other territories - there was competition between English and Belgian hardware. In 1822 two trade families from Brilon and Olsberg signed a contract in order to concentrate their capital in the Olsberger Hütte , which could thus exist for the long term. 35 years later there was still the Theodors and Olsberger Hütte in the Brilon district, where blast furnaces were operated. There were also a few fresh hammers; the small iron trade such as nail forging had also declined.

In the middle of the century, it was hoped that the railroad would take advantage of the ore deposits that existed. The railway connection of Olsberg in 1867 led to a short-term mining fever, but the production could no longer assert itself on the world market because the ore deposits were no longer the decisive location factor.

Mountain areas

The Sauerland , which was formerly Electoral Cologne, was divided into the mountain areas Arnsberg , Brilon and Olpe in Prussian times . These were subordinate to the Oberbergamt Bonn . The Arnsberg district included the Arnsberg district with the exception of the Warstein office . In addition, there were some offices in the Meschede district , some areas in the Iserlohn , Soest and Olpe districts . At times, the antimony mining at the Caspari colliery near Arnsberg also had a certain importance. In addition to the slate mining in the area of Fredeburg (combined mine Magog-Gomer-Bierkeller ) in the district of Meschede, whose main slate range in the Schmallenberg area extended to the slate mining areas in Lengenbeck and Nordenau , particularly the sulfur gravel mining near Meggen was of economic importance and Halberbracht in the Olpe district. The Olpe district largely coincided with the Olpe district . There were also individual offices in the Meschede district. Mining was of the greatest importance in the Brilon district. In addition to the area around Warstein in the Arnsberg district, this included most of the offices in the Meschede and Brilon districts . This area was not only the center of slate mining, especially around Nuttlar , but also the largest metal and iron ore mines, especially in the Ramsbeck area and near Niedermarsberg . Barite mining in Dreislar was a development in the 20th century .

The original territorial division was changed several times. In 1891, the Olpe-Arnsberg mining district was established, initially based in Attendorn, and since 1901 in Arnsberg. In 1907 this was renamed Revier Arnsberg. Including the Brilon district, the Sauerland mining district was founded in 1932, initially in Siegen and since 1937 in Arnsberg. This was declared the Sauerland Mining Authority in 1943. In 1965 it was merged with the Siegen Mining Authority.

Mining law

In terms of mining law , until the general Prussian mining law was introduced in 1865, the old mining regulations from the Electorate of Cologne from the 17th century, supplemented by various individual regulations, essentially applied . It was characteristic that even in Prussian times in the Sauerland the introduction of the management principle did not materialize. Apart from relics such as the miners' union, the miners differed only insignificantly from normal wage workers in the 18th century. On the other hand, the low level of government regulation of the mining industry facilitated entrepreneurial activity and the inflow of external capital through the establishment of joint-stock companies. These relatively favorable conditions had a positive economic impact on mining in the region. For the area of the Duchy of Westphalia there was the mining office of the Duchy of Westphalia from the 16th to the 19th century .

Economical meaning

Overall, mining in the Sauerland region experienced a considerable boom, especially in the decades after the middle of the century. While the total number of employees in the Brilon mining area in the 1840s was just 500 on average, the number of workers rose significantly in the 1850s, primarily due to the expansion of the Ramsbeck mining industry. In 1857 there were 1819 miners. In the 1860s to 1880s, an average of more than 2000 people were employed in the mining of this area. The number of miners reached their absolute peak at the beginning of the 1880s, when almost 3,000 men were employed in this area. With the decline in iron ore production and the stagnation in the field of non-ferrous metals, the number of miners also fell significantly. In 1899 the Oberbergamt in Bonn still had over 2000 workers in the Brilon mining area, including the neighboring principality of Waldeck . Just four years later, in 1903, there were fewer than 1,600 employees. After a new division of the mountain districts, in 1908 the new Arnsberg district, which included the Arnsberg, Brilon and Meschede districts, but no longer the mines in the Olpe district, only had a little more than 1,400 workers. In 1921, the chief mining authority in the Arnsberg district had just under 900 miners. This long-term loss of importance is also evident at the circle level. In the first decades of the German Empire, mining was the most important non-agricultural area of employment in the Meschede district. In 1882, more than 1,000 people were employed in mining and the metallurgical industry closely related to it. In total, those employed in mining and smelting accounted for around 20% of all those involved in craft, industry and mining. With over 1700 employees and a share of 30% of those working in the mining and manufacturing industries, the importance of mining and metallurgy was even higher in the Brilon district than in the neighboring district. The same applies to the district of Olpe, where around a third of all those active in the mining and manufacturing sector were also employed in the mining and steel industry. With a share of less than 3%, mining and metallurgy in the Arnsberg district hardly played a role.

At the end of the 19th century, the focus of regional mining had shifted more and more to the district of Olpe, especially as a result of the boom in pebble-sulfur mining. In 1907 more than 1200 and in 1925 still more than 900 people were employed in this area. In the district of Meschede the number of employees had already halved to less than 700 by 1907 and did not even reach 500 in 1925. The mining industry in 1907 with 67 employees in the Brilon district was completely insignificant. This number rose only slightly to 172 by 1925.

Not even 6% of the people employed in the craft, industrial and mining operations in the Meschede district still worked in the mining industry, in the Brilon district it was not even 3%. Within just a few decades, mining in the Brilon and Meschede districts had lost its importance as a central area of employment.

Development of individual pits and areas

Marsberg copper mining

This can be seen in the example of Marsberg copper mining. Although this could look back on a long tradition, it was only operated to a limited extent at the beginning of the 19th century. In the 1830s, foreign entrepreneurs then invested in the company. Another upswing was associated with the transformation of the old union into a joint stock company in 1856. The company dug new pits, combined the existing free float mining sites in one field and introduced new chemical techniques for separating ore and rock. In terms of workforce development and production output, the company's main expansion phases were in the 1840s and early 1860s. Due to falling ore prices, the development of the company stagnated in the following decades. At the end of the 19th century the workforce was only slightly higher than in the 1870s. After the First World War , the company's importance declined more and more. At first, ore mining was stopped until smelting was also given up during the Great Depression. In the course of preparations for war during National Socialism, copper mining in Marsberg was reactivated again and finally abandoned after the end of the Second World War .

Lead and zinc mining in Ramsbeck

In essence, the development in lead and zinc mining in Ramsbeck was also comparable . In this area, after 1815, initially driven by the Arnsberg tradesman Josef Cosack and largely financed by the Neheim entrepreneur Friedrich Wilhelm Brökelmann , the expansion of the pits, the consolidation of the fragmented property and the rationalization of mining methods began. This made the Ramsbeck union into the largest company in the Meschede district with at least 220 employees in the 1830s and 1840s. In the following years the union got into a crisis, which led to the closure of certain parts of the company and a drastic drop in the number of employees. A renewed upswing was associated with the transition of the company into the ownership of the "Rheinisch-Westfälischer Bergwerkverein" at the beginning of the 1850s. Under the leadership of the respected mining specialist von Beust , the company developed into by far the largest company in the Sauerland region. In 1853 the company employed 317 miners and 455 dump workers.

In 1854 the company merged with the " Stolberger Aktiengesellschaft für Bergbau, Lead- und Zinkfabrikation ". The now beginning era of operational development was characterized by an expansion that had been unprecedented for the Sauerland. With the aim of turning the Ramsbeck site into a European center for ore mining and processing, an enormous amount of capital was spent on building a number of processing plants and a large new smelting plant near Ostwig. A workforce of 2,000 to 3,000 men was planned, which was mainly recruited in the traditional mining areas of the Harz and Saxony . A number of workers' colonies were built to house them. The operational management was with Hans Max Philipp von Beust. However, the strategic direction lay with Henry Marquis de Sassenay.

The dream of a European mining center resulted in an unprecedented economic scandal for the region and high financial losses for shareholders. In the following years, the company was renovated on a realistic basis. One consequence of the restructuring was a significant reduction in the workforce from around 1,800 to an average of around 1,300 in the 1860s to 1880s. But even with this reduced workforce, the Ramsbecker Gruben were the largest employer in the region for decades. In the longer term, the fall in ore prices also had a negative impact on this operation. The mine management in Ramsbeck reacted to the changed market conditions with far-reaching rationalization measures. Since the end of the 1870s, under the direction of Carl Haber, drilling machines were introduced in the four main pits. In addition, older processing plants were replaced by more efficient operating parts. In addition, some no longer profitable mines and the smelting plants that were still in existence were closed. These measures also had an impact on the workforce. The number of workers has steadily declined since the mid-1880s. In the 1890s, the number of employees fell below the one thousand mark for the first time. This workforce reduction continued almost uninterrupted until the beginning of the First World War. In 1913 there were just 500 employees in the Ramsbeck district. As a result of the war and the upheavals of the post-war period, the number of workers fell further and reached its low point in 1920 with less than 300 employees, only to return to the pre-war level in 1926. Despite major problems, the company had at least survived the period of inflation and the global economic crisis before a certain upswing set in with the self-sufficiency policy of National Socialism. In 1974 the ore mine in Ramsbeck was converted into a mining museum with a visitor mine .

Iron ore mining in the Marsberg-Giershagen-Adorf area

In addition to non-ferrous metal mining, iron ore mining has also experienced a considerable boom since the 1860s in the Brilon mountain area and in the neighboring area near Adorf (“Martenberg” mine) in Waldeck . The reasons lay in a complete structural change in the ownership of the pits in the Marsberg - Bredelar - Giershagen area and following the connection of the region to the railway . In the place of regional trade unions and entrepreneurs, some Ruhr area corporations stepped up to secure their raw material base. The new development was announced as early as 1848 when a forerunner company to the Aplerbecker Hütte acquired the Eckefeld mine near Giershagen. With the transfer of the Ullrich family's mines to the Dortmunder Union , all of the major iron ore mines in the Brilon district were finally in the hands of groups from the Ruhr area. Since the beginning of the 1870s, the direct rail link with the coal mining area created the basis for the large-scale exploitation of the ore deposits. These changes initiated a hitherto unknown upswing in iron ore mining. The iron ore production in the entire district in 1840 was only around 13,000 tons and rose to 125,000 tons by the 1880s. This extremely positive economic development, especially for the remote Brilon district, turned out to be a short episode. Already towards the end of the 1880s, the production rates were falling rapidly. In 1897, the Eckefeld mine was the first major company to completely stop mining. Iron ore mining no longer played a role in this area by the turn of the century. This rapid loss of importance was due to technical innovations in the iron and steel industry of the Ruhr area . The chemical composition made the Sauerland ore only partially usable.

Iron ore mining in the Sundern area

In the first decades of the 19th century, mining and smelting in the Sundern area were of considerable economic importance. In the second half, however, mining played only a minor role, even if attempts were made again and again to tie in with pre-industrial traditions. In 1848 all iron ore deposits in the Sundern area were concentrated in two district fields. These awards were the starting signal for new prospects in this area. Smeltable ores continued to be mined only in the well-established Hermannszeche, Rotloh, Rosengarten and Michaelszeche mines. In order to find more information, individual tunnel projects were tackled. The workforce fluctuated a lot. In one quarter there were only 2 men, in another year 25 men worked in the mine. In 1874 the work came to a standstill, and from 1889-1894 the mine field was leased. At the turn of the century, new exploration projects were being worked on.

The last major tunnel project was the excavation of the Grillo tunnel in 1903. In 1905 the two unions consolidated under the name "Consolidated Iron and Manganese Ore Mines Bracht-Wildewiese". In the Wildewiese area, all mining was stopped in 1910, only the Hermannszeche was still in operation. The mine changed hands in the next few years and became part of the Christianenglück II trade union in 1932. In the meantime, it was decided to resume production in 1935; but it was given up again because of the less favorable ore analysis. In 1941 all work on the Hermannszeche mines was finally stopped.

Pebble-sulfur mining in Meggen and Halberbracht

Since the early 1850s, pebbles have been mined in the Meggen area , which was mainly used for the production of sulfuric acid . The company experienced an upswing primarily with the construction of the Lennetalbahn in the 1860s. Not only the chemical industry in Germany was dependent on this raw material, rather almost 2/3 of the production was at times exported. Some English mining companies even bought pits in the Meggen district. The development of cheaper Portuguese silica sulfur deposits ended the export boom and led the mining industry in Meggen and Halberbracht into a first crisis. The English mines became part of a company that was re-established in 1879 under the name of “Siegena Union”. The name refers to Siegen, the place of residence of the main shareholders. In addition, the "Sicilia Union" was formed as an amalgamation of smaller unions in the 1850s. Both companies were in constant competition with each other before they began to work together on various points in 1880.

With the upswing of the chemical industry during the founding years in Germany, sales opportunities improved significantly. In 1871 there were a total of 175 pits and 6 hereditary tunnels in the area. The great depression that began in the mid-1870s meant another economic setback, even if the company also began to mine heavy spar . It was only after 1900 that sales of pebbles stabilized.

During this time, the company of the chemist Rudolf Sachtleben developed a process for the use of previously unusable remains of the silica sulphurous production for the production of lithopone . For the later factories of Sachtleben Chemie , the pits in the Sauerland became the most important source of raw materials. Initially, Sachtleben only signed a cooperation agreement with the existing trade unions. In 1906 there was a merger with the Siegena union under the name “Union Sachtleben” based in Homburg . In 1913 Sachtleben acquired the majority of the Kuxe of the Sicilia union from Count Landsberg von Velen and Gemen and other shareholders. Both trade unions remained independent legal bodies, but they were actually operated as one company. In the years before the First World War, the annual production was 150,000–200,000 t.

The pebble and barite mining around Meggen and Halberbracht experienced a significant boom in the First World War, precisely because of its importance to the war effort (in contrast to almost all other mining operations in the Sauerland). The workforce increased from 1,500 men in 1915 to almost 3,000 workers in 1918, and the production volume was 700,000 tons. During the Weimar Republic , Frankfurter Metallgesellschaft AG acquired part of the shares in both unions. With this financial support through the acquisition of smaller pits, they were able to combine the entire mining process in one hand. At the end of the 1920s, the Meggen mines were the leading barite and gravel pits in the world. The share of barite world production was 22% and the share of German pyritic sulfur production was 25%. During the Second World War, the mines were also important to the war effort and experienced a further boom. In 1943 a total of over 4,000 workers were employed, including many forced laborers and prisoners of war, and an annual production of over 1 million t was achieved.

After the Second World War, rationalization measures resulted in massive staff cuts, but the mining industry remained efficient. From the late 1980s onwards it became clear that the economically viable deposits were largely exhausted. The final cessation of production took place in 1992. The mining facilities such as mine dumps and tailings ponds are still visible today in many places in the vicinity of Meggen.

Mining in the Warsteiner area

In the 19th century, the shortage and increase in the price of charcoal (with the simultaneous appearance of coke smelting in the Ruhr area) led to the cessation of pig iron production in Warstein. Mining came to a standstill and all mines were closed. The connection of Warstein to the railway network of the "Warstein-Lippstädter Eisenbahn Gesellschaft", the later WLE , in 1883 enabled ore to be transported to the relatively nearby Ruhr area, which led to the resumption of mining in some areas: David mine, Suttbruch mine, Rome mine, Hirschfeld mine.

Mining was carried out at numerous locations in Warstein. Most of the locations that can still be identified today probably go back to modern mining in the 18th and 19th centuries, but earlier dating cannot be ruled out for individual locations. The Hirschfeld pit was located in the middle of today's development. The Stillenberg in Warstein represented a larger, coherent mining area . Many traces of pings, shafts, tunnels and heaps can still be made out here. Until the late 19th century, the Martinus mine was mined. The mining area of this pit was then used as an open-air stage for the psychiatric clinic from the early 20th century. The Suttbruch mine was located on the slope of the Lörmeckal , it was producing until 1923. In the Schorental , traces of mining can be seen that point to the “St. Christoph ”(consolidated from four smaller mines), but also include older mines. At least two mining sites can be found in the adjacent Bermecketal - one of them the “Georg” pit. The “Siebenstern” mine was a larger open-cast mine in Kahlenberg. The "David" pit near the Bilstein cave is of particular importance. Its closure in 1949 put an end to iron ore mining in the Warsteiner area.

Customs and traditions

Until the 20th century, a special religious tradition and the veneration of certain saints was widespread among the miners in the region. Saint Anthony of Padua , Saint Anne , Saint Barbara and Pope Silvester were venerated. A specialty in north-west Germany was the veneration for St. Joseph in the area of Olpe. For Saint Anthony of Padua there was even a chapel in his honor near the copper mines since the 16th century. In Marsberg, it was common to pray together before the start of the shift until the 20th century. In many places the miners did not drive in, also up into the 20th century, on New Year's Eve on December 31st or on the Remembrance Day of St. Barbara on December 4th and instead attended a joint service.

An unusual combination of religiosity and mining is a way of the cross in the Elpe valley near Wulmeringhausen (route from location to location ). On a steep miner's path to the Aurora pit, miners used knife carvings in the 19th century to carve simple representations into the bark of trees. Originally there are probably fourteen stations of the crossroads. Some of the representations are still visible today. The carvings were not only used for religious edification, but also as signposts.

After the end of mining, visitor mines or similar facilities were created in various places in the region to commemorate them. These include the Kilian tunnel in Marsberg, the visitor mine in Ramsbeck , the tunnel in the Eisenberg mine between Brilon and Olsberg, the Dreislar heavy spar mine , the Holthausen slate mining and local history museum and the Siciliaschacht mining museum in Meggen. There are also associations such as the miners 'band in Fredeburg or the miners' association in Giershagen, which are in the mining tradition.

Working group "Mining in the Sauerland"

In 2001 the working group “Mining in the Sauerland” was founded, supported by the Historical Commission for Westphalia and the Westphalian Heimatbund . He set himself the task of expanding knowledge about historical mining in the Sauerland and also to publish it in a suitable form. Public conferences and smaller expert discussions were increasingly popular. The working group ensures better interlinking of scientific research in offices and archives and research in the various cities and municipalities.

The results of the public conference in 2005 in Ramsbeck were published in a conference volume (cf. literature "Mining in the Sauerland. Westphalian mining in Roman times and in the early Middle Ages. Conference volume"). A first overview of the state of mining research appeared in spring 2008 (literature: "Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period"). In addition, the Internet portal "Westphalian History" maintains a detailed collection of data with sources, registers and points of discovery, which makes mining, smelting and hammer works in large numbers researchable.

literature

Older literature

- Ludwig Hermann Wilhelm Jacobi: Mining, metallurgy and trade in the administrative district of Arnsberg in statistical representation . Iserlohn 1857.

- Oberbergamt Bonn (Hrsg.): Description of the mountain areas Arnsberg, Brilon and Olpe as well as the principalities of Waldeck and Pyrmont . Bonn 1890.

- Georg Fischer: About the genesis and future possibilities of mining the Central Devonian red iron ores in the Brilon area . Berlin 1929.

Newer literature

- Karl Peter Ellerbrock, Tanja Bessler-Worbs (ed.): Economy and society in south-eastern Westphalia. Society for Westphalian Economic History, Dortmund 2001, ISBN 3-925227-42-3 . In this:

- Stefan Gorißen: A forgotten area. Iron ore mining and metallurgy in the Duchy of Westphalia in the 18th century. Pp. 27-47;

- Jens Hahnwald: Black brothers in red underwear ... workers and the labor movement in the Arnsberg, Brilon and Meschede districts. In: Ibid., Pp. 224-275.

- Wilfried Reininghaus, Georg Korte: Trade and commerce in the districts of Arnsberg, Meschede, Brilon, Soest and Lippstadt 1889–1914. In: Ibid., Pp. 132-173.

- Heinz Wilhelm Hänisch: Calcite mining on the Brilon plateau. Self-published, 1996.

- Heinz Wilhelm Hänisch: The metal, slate, barite and marble mining from 1200 to 1951 on the Brilon plateau . Ed .: Heinz Wilhelm Hänisch, 2003.

- Miriam Hufnagel: Contributions to the history of mining in the Olpe district. Part 2: Mining in Meggen and Halberbracht and its effects on the settlement structure of both places. Series of publications of the district of Olpe No. 26, publisher: The Oberkreisdirektor des Kreises Olpe, Olpe 1995, ISSN 0177-8153 .

- Reinhard Köhne (Hrsg.): Mining in the Sauerland. Westphalian mining in Roman times and in the early Middle Ages. Conference proceedings . Westfälischer Heimatbund, Münster 2006, ISBN 3-928052-12-8 .

- Reinhard Köhne: Historical mining in the Sauerland ("Westphalian Ore Mountains") (PDF; 762 kB). In: Geographical Commission for Westphalia / LWL (ed.): GeKo Aktuell, issue 1/2004. Münster 2004, ISSN 1869-4861 , pp. 2-10.

- Jan Ludwig: Ramsbeck ore mining 1740–1907. In: Conference proceedings (old) mining and research in NRW 2012 [1]

- Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period . Publications of the Historical Commission for Westphalia XXIIA Vol. 18. Aschendorff Verlag, Münster 2008, ISBN 3-402-15161-8 .

- Michael Senger (editor): Mining in the Sauerland . Publisher: Westphalian Slate Mining Museum Schmallenberg-Holthausen , Schmallenberg-Holthausen 1996, ISBN 3-930271-42-7 .

- Martin Strasbourg: Archeology of the Ramsbeck mining . Publications of the Antiquities Commission in Westphalia. In R. Köhne, W. Reininghaus, Th. Stöllner (Hrsg.): Mining in the Sauerland: Westphalian mining in Roman times and in the early Middle Ages (= writings of the Historical Commission for Westphalia, 20). Münster 2006, pp. 58-82.

- Martin Straßburger: Castles, caves, graves: the first iron in the Sauerland . Accompanying publication to the special exhibition in the ore mining museum Ramsbeck from August 1st to December 2nd, 2006. Bestwig 2006.

- Martin Straßburger: Plumbi nigri origo duplex est - lead mining during the Roman Empire in the northeastern Sauerland . In W. Melzer, T. Capelle (ed.): Lead mining and lead processing during the Roman Empire in the Barbaricum on the right bank of the Rhine (= Soest contributions to archeology, vol. 8). Soest 2007, pp. 57-70.

- Martin Straßburger: Archeology and history of the Ramsbeck mining industry from the Middle Ages to 1854 . Der Anschnitt 59, 2007. H. 6, pp. 182-190.

- Martin Vormberg, Fritz Müller: Contributions to the history of mining in the Olpe district. Part 1: Mining in the Kirchhundem community. Series of publications of the district of Olpe No. 11. Olpe 1985, ISSN 0177-8153 .

- Gerhard Hausen: Forced Labor in the Olpe District , Volume 32 of the Olpe District Series of publications, self-published, 2007, ISSN 0177-8153 (232 pages).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Term based on: Stefan Gorißen: A forgotten area. Iron ore mining and metallurgy in the Duchy of Westphalia in the 18th century. In: Karl Peter Ellerbrock, Tanja Bessler-Worbs (Hrsg.): Economy and society in south-eastern Westphalia. Society for Westphalian Economic History, Dortmund 2001, pp. 27–47.

- ^ A b Wilfried Reininghaus: Saltworks, mines and ironworks, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , p. 721.

- ^ Michael Bode, Andreas Hauptmann, Klaus Mezger: Reconstruction of early imperial lead production in Germania: Synergy of archeology and materials science. In: Walter Melzer, Torsten Capelle (ed.): Lead mining and lead processing during the Roman Empire in Barbaricum on the right bank of the Rhine. Soest Contributions to Archeology, Vol. 8. Soest 2007, p. 109.

- ^ A b Norbert Hanel, Peter Rothenhöfer: Germanic lead for Rome. On the role of Roman mining in Germania on the right bank of the Rhine in the early Principate. With a contribution by Stefano Genovesi. In Germania 83, 2005, pp. 52-65.

- ↑ Heinz Günter Horn (Ed.): Theiss Archaeological Guide Westphalia-Lippe. Stuttgart 2008, pp. 174-176; Reinhard Wolter: The battle in the Teutoburg Forest. Arminius, Varus and Roman Germania. Munich 2008, p. 70.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010, p. 115.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010, p. 115f.

- ↑ a b c d e Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010, p. 116.

- ↑ Kristina Nowak-Klimscha: The early to high medieval desert Twesine in the Hochsauerlandkreis . Settlement development on the border with the Franconian Empire. In: Soil antiquities of North Rhine-Westphalia . No. 54 . Philipp von Zabern, Darmstadt 2017, ISBN 978-3-8053-5122-5 .

- ^ To Oelinghausen: Bernhard Padberg: Oelinghausen and his monastery economy. In: Werner Saure (Ed.): Oelinghauser contributions. Freundeskreis Oelinghausen eV, Arnsberg 1999, pp. 66-69.

- ^ A b Wilfried Reininghaus: Saltworks, mines and ironworks, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , p. 722.

- ^ Fritz Bertram: Mining in the area of the district court Plettenberg. 1952.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and ironworks, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , p. 723.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 750f.

- ↑ a b Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010, p. 117.

- ↑ Gogericht Brilon inventory book ( Memento of the original from October 8, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Mining in Sundern-Hagen, accessed on July 9, 2010 ( Memento of the original from January 6, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Bernhard Göbel and others: The upper Sauerland. Country and people. Bigge 1966, p. 63.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010, p. 217.

- ^ A b c Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010, p. 118.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: The Electoral Cologne Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 748f.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The history of mining in the Cologne Sauerland. An overview. In: Sauerland 3/2010, pp. 118f.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 751f.

- ↑ Jens Foken: Cities and Freedoms in the Early Modern Age. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: The Electoral Cologne Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 386ff.

- ↑ compiled from: Hermann Brassert: Berg-Ordnungs der Prussischen Lande. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, pp. 517-521.

- ↑ Clemens Liedhegener: Authorities Organization and enforcement personnel in the Duchy of Westphalia in the late 16th century. In: De Suerlänner, born 1966, pp. 95ff.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 753ff.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 754f.

- ^ A b Wilfried Reininghaus: Saltworks, mines and ironworks, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: The Electoral Cologne Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia up to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , p. 756.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia up to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , p. 743.

- ^ A b Wilfried Reininghaus: Saltworks, mines and ironworks, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , p. 724.

- ↑ cf. Frank-Lothar Hinz: The history of the Wocklumer ironworks 1758–1864 as an example of Westphalian noble entrepreneurship. Altena 1977.

- ↑ compare on noble mining in the Canstein lordship: Horst Conrad: The owners of the Canstein lordship and their mining. A contribution to the history of mining in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Old Kingdom, Part I. In: Westfälische Zeitschrift, Vol. 160/2010, pp. 187–205 ( PDF file ). Ders .: The owners of the Canstein estate and their mining. A contribution to the mining history in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Old Kingdom, Part II. In: Westfälische Geschichte, vol. 2011, pp. 219-252 ( PDF file ).

- ↑ compare: Stefan Baumeier, Katharina Schlimmgen-Ehmke (ed.): Golden times. Sauerland economic citizens from the 17th to the 19th century. Essen 2001.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 724f.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 742f.

- ↑ a b c Stefan Gorißen: Westphalia's most backward province? Iron ore mining and smelting in the Sauerland region of Cologne in the 18th century. In: Golden Times. Klartext, Essen 2001, p. 14ff.

- ^ Volker Wrede: Roofing slate mining in the Sauerland. (doc; 83 kB)

- ↑ State Archives NRW, Dept. Westphalia: General files of the Sauerland Mining Authority

- ^ Heinrich Schauerte: patron saint in mining in the Sauerland. In: Patrone and Saints in the Sauerland region of Cologne. Fredeburg 1983, pp. 101-104.

- ^ Fritz Droste: The Aurora mine in the Elpe valley. The Way of the Cross on the Bergmannspfad led to work. In: Yearbook Hochsauerlandkreis. 1994, pp. 114-117.

- ↑ Kur- und Knappenkapelle Fredeburg ( Memento of the original from March 19, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ page City of Marsberg ( Memento of the original from July 27, 2009 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

See also

- List of mines in the Sauerland

- Mining in Siegerland

- Lahn-Dill area

- Hammer mills in the Sauerland

- Slate mining in South Westphalia

Web links

- Westphalia regional: Miners' colonies in the Ramsbeck district

- Old mining in the Sauerland

- Lead ore mining Roman Empire

- Page about mining in South Westphalia

- Ore mining in Westphalia - an overview. Geology and mining. Books from the historical library of the North Rhine-Westphalia State Mining Authority in Dortmund. Editors Christoph Bartels, Reinhard Feldmann and Klemens Oekentorp. Writings from the University and State Library of Münster, the Geological-Paleontological Museum of the University of Münster and the German Mining Museum in Bochum. Münster 1994, Vol. 11, pp. 35-68.