Mining Office of the Duchy of Westphalia

The mining authority of the Duchy of Westphalia (partly Upper mountain office called) which was mining authority for the product to the Electorate of Cologne part of Duchy of Westphalia . It dates back to the 16th century and lasted into the 19th century. Among other things, it was responsible for mining in the Sauerland and the iron and steel works in the region. The mining authority did not initially have a permanent seat. Only gradually did Brilon develop into a permanent place of work. A sub-mining office was located in Olpe . In the long term, the mining authority turned out to be not strong enough to enforce its competencies. After the 1680s, the authority slowly lost its economic policy options, while the influence and self-interests of the miners gained weight. Since 1692 at the latest, the authority was subordinate to the Electoral Cologne Court Chamber in Bonn . However, it had primarily fiscal interests and was less interested in sustainable economic development or technological modernization. Both were reasons why the Duchy of Westphalia could not make use of the resources available.

backgrounds

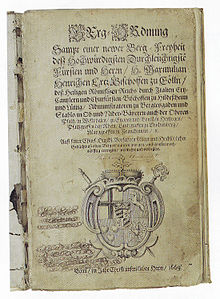

Mining was of great economic importance for the Duchy of Westphalia, which belongs to Kurköln. For fiscal and economic reasons, too, it was of great interest to the electorate as a whole. Against this background, the sovereigns tried to promote mining in the region and to regulate it according to their needs. Six mountain orders have come down to us from the period between 1533 and 1669 alone . In the mountain regulations, the development of the mountain administration is also reflected on the normative level. The provisions made there, however, rarely coincide with reality. In many cases, the provisions of the mountain regulations were much more detailed and comprehensive than the implementation in practice.

Tasks and structure

Among the most important tasks of the mining administration of the oral belonged Mountain tithes and the development of new sources of tithing. The income was offset against the expenses and the surpluses were transferred to the court chamber in Bonn. In addition, the Mining Authority granted the rights to speculate and was responsible for the mortgages. There was hardly any supervision of the actual mine operation, as it was characteristic of the management principle in the neighboring county of Mark . Another problem was that the miner captain was usually a nobleman with no specialist knowledge. This would have been less of a problem if the mountain master had always been up to the task. But that wasn't always the case. Although the principle of written form was introduced early on , there was a lack of meaningful seiger cracks or similar documents, especially for older or disused pits . This made it difficult to resume operations later. The mining authority was also responsible for the supervision of the iron and steel works. So it had to check the functional equipment of the blast furnaces and the professional training of the staff. Furthermore, the Mining Authority was the court instance for all conflicts related to mining, smelting and hammering. Depending on the situation on either side of the Ruhr, the conflicting parties either had to contact the Oberbergamt in Brilon or the Unterbergamt in Olpe. The Oberbergamt reserved jurisdiction over the Unterbergamt. The court of appeal was the court councilor in Bonn.

At the end of the old empire, the structure of the mining office was roughly as follows: In addition to the headquarters in Brilon, a branch in Olpe was added around 1650. At times, the two districts of the two offices were later referred to as quarters as mountain districts . The Ruhr was essentially the border. The Oberbergamt in Brilon was superordinate to the two districts. The staff, also responsible for the Brilon Revier, consisted of a mining captain, a mining master, a mountain clerk , a mountain toe and a mountain jury each for the areas of responsibility of Brilon and Olpe. The mountain clerk had to keep the mountain books and draft contracts. The mountain toe was responsible for collecting the tithe. The mountain jury visited and checked the pits, huts and hammers on site. The Unterbergamt in Olpe was led by an Unterbergmeister and a Bergschreiber. The mining officials were employed by the elector without the influence of the estates and taken on oath. According to the mining regulations of 1676, inspectors, shift foremen , foremen , steers , smelters and hammer smiths were subordinate to and obliged to the mining authority .

After Hesse-Darmstadt took over the state in 1803, the Brilon and Olpe mining offices were merged and the mining office was relocated to Eslohe . A description of the organization of the mining administration has been preserved from 1815 - shortly before or after the land was taken over by the Kingdom of Prussia . Then there were the two main mountain areas Brilon and Olpe. Each was presided over by a mountain master as well as an upper and lower mountain jury. The mountain districts were divided into districts, for each of which a mountain jury was responsible. Their seats were in Brilon, Ramsbeck , Thieringhausen (near Olpe) and Sundern . More Mountain officials were the Bergrichter , the mountain scribe who Markscheider and Bergbote. The officials of the mining authority met every week for a joint meeting. The mountain jury and mountain champion who were sitting at a distance came in every fortnight. The mine surveyor was only called in when his expertise was necessary. After 1810 there was no appointment of a chief miner. In legal matters, the Mining Office was subordinate to the government in Arnsberg . In camera and mountain police matters, the court chamber in Darmstadt was the superordinate authority.

history

Development until the end of the 16th century

In the late Middle Ages only rudiments of a mountain administration or mountain jurisdiction existed . This was still closely connected with forestry. The wood judges in the Endorf area also claimed mountain jurisdiction. This was still the case in 1530 in a document for the trades on the Endorfer Erbenstein. As a result, forest and mountain management differentiated. But until the 18th century, a nobleman always held the offices of chief hunter and miner in personal union.

In the mining regulations of 1533, the responsibility under mining law was transferred from the wood judge to a lordly appointed miner . In addition, a trend towards writing can be seen. A mountain clerk had to keep a mountain book and the payment of the mountain tithe was recorded in writing. A separate mountain judge did not yet exist. Instead, this task was taken over by the mountain master. There were also lay judges , half of whom were selected on the basis of land law and mining law . In the mining regulations of 1549 it was then stipulated that the miners were allowed to choose a mountain judge and lay judge to resolve internal disputes. The court of the miner, however, was responsible for all other mining law matters.

In connection with the mining regulations of Elector Anton von Schaumburg , the latter issued an edict in which the appointment of a mountain bailiff and a mountain master was announced.

During the short period of the reign of Gebhard von Mansfeld (1558–1562), officials from Mansfeld took over the mining administration in the Duchy of Westphalia. A Johann Braun was appointed Landbergmeister. However, this subsequently proved to be unreliable. One aspect of the mining regulations issued by Elector Gebhard von Mansfeld in 1559 concerned the transfer of the organizational principles of the mining administration common in the Saxon and Bohemian regions to the Duchy of Westphalia. Numerous functionaries with far-reaching responsibilities were named. However, these provisions did not correspond to the actual conditions and were of a purely normative character.

The development in the following period is not entirely clear because of the poor tradition. A mining authority in Endorf had existed since the 1570s at the latest. It was subordinate to the land miner Leonhard Lehner. This was an external mining expert. After his death in 1572 there were internal problems within the mining authority. There were embezzlements and the then mountain master was dismissed. His post remained vacant for some time and the necessary business was taken care of by the Landdrost in Arnsberg .

High point in importance in the 17th century

The situation was stabilized under Elector Ernst von Bayern , who was very interested in the mining industry. In his day there were initially two mountain masters. Georg Reitzer officiated and lived in Meschede and occasionally in Brilon. Hans Joachim Lautenschläger was responsible for the western and southwestern parts of the duchy and officiated in Endorf. After Reitzer's death, Lautenschläger was responsible for the entire area. Among other things, as a reaction to his demand for previously unknown taxes, there were conflicts with the Landdrosten, various bourgeois trades and aristocratic operators of smelters and hammer mills. Probably to calm the situation, Ernst von Bayern waived all tithes from mining for 18 years in 1605.

In the decades before the start of the Thirty Years' War , the coal and steel sector experienced an upswing. Although there was a first meeting of the mining officials in 1609, the mining administration did not intervene in the development. At that time your tasks were evidently primarily in the fiscal area. The Thirty Years War itself damaged the coal and steel industry, but not completely ruined it. After the death of Bergmeister Lautenschläger, his post initially remained vacant. Caspar Engelhardt took over the post around 1640. Formally superior to the miner, the noble miners were first Raab Gaudenz von Weichs and then Ferdinand von Wrede . Elector Maximilian Heinrich von Bayern , who had been in office since 1650, endeavored to restore the mining industry from a mercantilist point of view.

A detailed report by the miner revealed the poor condition of the mining industry. In addition to numerous other reasons, he also pointed out the efforts of certain interested parties to undermine the miner's rights. "High and low officials, judges, offices and others agitate the berckmeister in his function, has no parition according to the ordinance, the executiones are denied to him and denied to confuse the ordinance, do not want to allow him to refrain from and inhibit the excess sticks according to the regulations and to tighten vertical rights. ” As a consequence, he called for a new version of the mining regulations and an expansion of the competencies of the mining administration.

Engelhardt's successor as Bergmeister Christoph Frantze , based in Meschede, began working on new mining regulations immediately after taking office. These mountain regulations also determined the role of the mountain officials. The staff of the mines were subordinate to the court chamber and the miner. Their number was again very high and, as with the old mountain order, did not correspond to reality.

The mining captain was supposed to find out about mining matters and took a ministerial position. Among other things, he was assigned full mountain jurisdiction . The judges of the mountain freedoms (i.e. the minority of the mountain town ) were now subordinate to him. The written form of administration was also increased. The mountain clerk now had five different books to keep. The general mountain book had a public character and the mountain clerk was given the right to keep his own seal. As far as is known today, none of the mountain books has survived. The attempt made with the new mountain order to regulate the mining industry in the sense of absolutism and mercantilism, however, met with the opposing forces of the miners and the estates . Even the comprehensive claim to jurisdiction met with resistance and rejection from owners of the Padberg , Alme or Canstein estates . The Padbergers went so far as to arrest the electoral mountaineers.

After Frantze's involuntary retreat in the 1680s, the mining administration began to lose creative influence, while the freedom of those involved in the assembly industry increased. In retrospect, this was a turning point. The administration found it increasingly difficult to implement the provisions of the Bergordnung. After all, it was almost entirely on paper. This weakness of the mining authority was in the long run a reason why the duchy could not use the resources available.

The weakening also had to do with the fact that the office of miner was initially not filled again. This did not happen again until 1696. During this time, the mountain captain von Weichs had a significant influence on the mining policy. To protect the local mining industry, he tried to prevent the import of ores from neighboring areas. There was a conflict between the mining office and the court chamber in Bonn. While the mining office demanded customs barriers, the court chamber pleaded for the unhindered importation of ore. The ban on exporting charcoal from the duchy was hardly observed, which was also a sign of the weakness of the mining office.

Loss of importance in the 18th century

In the years 1710/1711 the conflict over the export of iron escalated. The Mining Authority not only set an example on a dealer by imposing high fines, but also generally retroactively imposed a special levy on exported goods for five years. This led to protests, especially from Reidemeisters from the Assinghauser Grund , who were supported by other interested groups. The state parliament dealt with the issue and the state estates saw this as a violation of the Hereditary Land Association . This basically tied new taxes to the approval of the stalls. The Reidemeister also called the Cologne Cathedral Chapter and this was at least ready to talk. Because Elector Joseph Clemens of Bavaria was in exile at this time, the cathedral chapter also held secular rule in Kurköln and the duchy. A deputation of the state parliament at the cathedral chapter achieved de facto the abolition of the punitive tariff and compensation for the punished Reidemeister. The validity of the Bergordnung as such was even questioned. This defeat meant a serious loss of reputation for the mining authority.

In addition to the previous functionaries, there was also the position of a mountain administrator in the first half of the 18th century. The post was established because the ministerial office had developed into a largely representative office in the early and mid-18th centuries. The office was held by members of the Kannegießer family until 1763. Your activity in this function was largely limited to the area around Brilon. The mountain manager Herold had made various suggestions for improving the mining system, and thus encountered resistance from Johann Heinrich Kannegießer , among others, and he resigned the post around 1723. The mountain supervision was thus with the miner, who also had to manage the forestry. The actual work was therefore carried out by the Bergschreiber and Berg toeer. Only when Heinrich Kropff took up the post of miner in 1763 did this regain its practical importance.

Between 1730 and 1743 there was a dispute between the estates on the one hand and the court chamber and the mining office on the other hand over the extensive jurisdiction over mining law issues of the mining office. The state parliament, which was sent from the nobility and cities, saw economic freedom of action in danger as a result. In 1730, Elector Clemens August von Bayern had an investigative commission set up under the miners' captain von Weichs. The Mining Authority reaffirmed its claims to regulatory interventions, for example with regard to the charcoal trade in the sense of mercantilism. Nevertheless, the court chamber evidently gave in to pressure from the estates and drafted an edict that threatened to severely restrict the powers of the mining office. Outside of Brilon's office, the mining authority should no longer be responsible for the charcoal issue. Quarries should also be removed from the mining authority's control. The draft was initially not implemented and further expertise was subsequently obtained, for example from the Saxon mining administration. Finally, the electoral government came to the conclusion that too far-reaching control would be detrimental to the metal industry. In 1743 the amended edict was issued. After that, the mining authority should only be responsible for disputes in the construction or repair of huts, hammers or charcoal sheds. Its jurisdiction was essentially limited to matters that directly affected the mines or miners. In particular, the mining authority thus lost most of its influence over charring. It has previously tried to intervene strongly in this area.

As a result, the mining authority's influence on economic policy was even more limited. However, it continued to perform the core tasks such as speculation, lending, the approval of smelting works and hammer works and remained responsible for the collection of the tithe. The Mining Authority was in contact with the mountain jury and Steigern and tried to regulate the conditions of the miners. This workers' policy did not go as far as the general privilege in the county of Mark of 1767. In 1743 the mountain jury and senior officers in the offices of Menden and Balve were asked to submit quarterly accounts and to supervise the miners properly. The regulations were expanded further in 1749. A prayer was now compulsory before entering and leaving. The climbers had to handle light and powder carefully and they should be an example to the miners. The Steiger should be polite to them and rule them with “common sense”. The miners were sworn to adhere to working hours and to work carefully.

In contrast to the management principle in the neighboring county of Mark, there was hardly any supervision of the actual mine operation . There was only limited supervision by mountain jury members and shift supervisors. The tasks of the mining authority also included the supervision of the iron and steel industry, although it had already lost many competencies in this area. The mining authority had to check the functionality of the blast furnaces and the knowledge of the smelter.

End of the Electoral Cologne period

Under Maximilian Friedrich von Königsegg-Rothenfels , approaches to a technical modernization of the mines and smelters began. The work of the miner Philipp Kropff had a positive effect. Later his son Johann Heinrich Kropff held the office from 1777 to 1807. Friedrich Joseph von Boeselager , appointed miner captain in 1781, was ignorant and eventually suffered from dementia. He left the actual work to the mountain masters in Olpe and Brilon. Friedrich Wilhelm von Spiegel , who had already been made a mountain ridge in 1801, took up the position of mining captain in 1804, but died in 1807.

Although there was a need for action, there was no significant reform of the mining authority. Franz Wilhelm von Spiegel , former Landdrost in Arnsberg and then an influential minister in Bonn, has been trying to do this since 1786. He brought the professor of mineralogy Anton Wilhelm Arndts , who, like von Spiegel himself, had mountain property in the Sauerland, as a consultant for mining matters at the court chamber. He wrote a report on the grievances in mining from 1794. In 1802, a cousin of Friedrich Arndt wrote another report. Both agreed in their conclusions. The mining officials had too little expertise, had no idea about mining and the mining books were poorly kept. The miners could act as they wanted without having to fear government intervention. This led to overexploitation, which in turn damaged the sovereign's tithe income. In addition, the noble miners did not have sufficient mining or at least legal knowledge. As long as the miners were specialists, this could be compensated. But even with these, not everything was always in order. Von Spiegel complained in 1784 that the miner at the time, at least in parts, only had inadequate specialist knowledge and would exercise his function too casually. There was also a lack of precise documents, especially for older mines and businesses. The miner would also not drive the trades sufficiently to operate their works. The aim was therefore to modernize the mining administration based on the Prussian model as it existed in the neighboring county of Mark. The planned establishment of chairs for physics, mineralogy, mechanics and metallurgy to improve education at the end of the empire no longer came about.

After Hesse-Darmstadt took over the Duchy of Westphalia, Anton Wilhelm Arndts became the main consultant for the mining sector at the government in Arnsberg and again wrote reports on the reform of the mining sector. But even in the Hessian period it was not possible to modernize the mining industry from the ground up. The old Brilon Mining Authority was relocated to Eslohe and the Unterbergamt in Olpe was dissolved.

Unterbergamt Olpe

There was a certain special development in the Olpe area. The distances were too far to manage the entire mountain system from one place. Already in 1506 a miner was named for the Waldenburg office . In 1596 a mountain master was mentioned in Stachelau . In Olpe, a Caspar Engelhardt - a relative of the aforementioned Bergmeister Engelhardt - appeared as a Bergmeister around 1603. Gradually, a separate administration for the mining industry in the Olpe area developed. In 1659, in addition to the mountain master, a mountain clerk and a mountain jury were named. In 1724 a fixed mountain toe was also planned for this area. Apart from the distance, there were also economic interests in this area that were difficult to reconcile with the mercantilist policies of the Brilon Mining Authority. Olpe was dependent on the import of pig iron from the Siegerland . Partly processed into sheet metal, it was exported to Bergisch and Märkische. The push for its own mountain administration was successful. In 1740 a mining authority was set up in Olpe. De jure, the Mining Authority in Brilon retained supervision over Olpe, but de facto the Mining Authority there acted largely independently of Brilon. Own mountain books were kept and decisions about mining law were made. In 1767 there was a sub-miner, a mountain toe, a mountain clerk and a mountain messenger in Olpe.

Accommodation

The mining administration initially had no permanent seat. The seat was where the mountain master or, previously, the mountain judge lived. This was initially the case in Endorf or Meschede. At the time of the mining captain Gaudenz von Weichs, Hirschberg , seat of the forest administration, was also the place of the mining administration. Since the beginning of the 17th century there was at least one mountain tithe in Brilon. Even later, the officials did not necessarily have to be in Brilon or Olpe. Only the Bergschreiber was compulsorily located there. Only in the 18th century did Brilon really become the center of the mining administration.

The accommodation of the mining office in Brilon was therefore rather provisional until about the middle of the 18th century. The mountain manager Herold was unable to rent or build a building around 1717 because he encountered resistance from the mayor and miner Johann Heinrich Kannegiesser . He was disconcerted that he had to pay rent for the apartment in the “electoral house” - which had recently become municipal property. The registry was in the Bergzehntner's house. When a fire broke out in the neighboring house and endangered the documents, the court chamber approved money for the construction of a small, fire-proof building. A mountain room was also built. The Mining Authority's negotiations with the Reidemeisters were also held there. House Hövener on Briloner Markt was probably the seat of the mining administration for a few years after the turn of the 19th century.

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: The Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 p. 754.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 77.

- ^ Aloys Meister: The Duchy of Westphalia in the last period of the Electoral Cologne rule . Münster, 1908 pp. 73-75.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 p. 755.

- ^ History of the Warsteiner Gruben- und Hüttenwerke Aktiengesellschaft. Typescript, 1938 p. 81 f.

- ^ Aloys Meister: The Duchy of Westphalia in the last period of the Electoral Cologne rule . Münster, 1908 p. 73.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: A description of the mining office of the Duchy of Westphalia by Anton Wilhelm Arndt from the year 1815. In: Südwestfalenarchiv Jg. 2011 p. 165 f.

- ^ Aloys Meister: The Duchy of Westphalia in the last period of the Electoral Cologne rule . Münster, 1908 p. 73.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 68.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 75 f.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg. 1996 p. 164.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 76.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 81.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 83.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 pp. 84–86.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 pp. 87-90.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 90.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 93.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg. 1996 pp. 160-162, 165.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: The Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 p. 754.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 pp. 101-104.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 pp. 105-107.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 110.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 113 f.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 p. 755.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 116.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: The Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 p. 754.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 117.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 118.

- ^ Aloys Meister: The Duchy of Westphalia in the last period of the Electoral Cologne rule . Münster, 1908 p. 74.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and smelting works, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: The Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 p. 754.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: A description of the mining office of the Duchy of Westphalia by Anton Wilhelm Arndt from the year 1815. In: Südwestfalenarchiv Jg. 2011 p. 162 f.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 112.

- ^ History of the Warsteiner Gruben- und Hüttenwerke Aktiengesellschaft. Typescript, 1938 p. 81.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg. 1996 p. 165.

- ^ Reininghaus, Wilfried; Köhne, Reinhard: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 108.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg. 1996 p. 165.

literature

- Aloys Meister : The Duchy of Westphalia in the last period of the Electoral Cologne rule . Münster, 1908 pp. 73-75.

- Horst Conrad: The mountain order of the Electorate of Cologne in 1669 and its surroundings. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg. 1996 pp. 153-172.

- Horst Conrad: A description of the mining office of the Duchy of Westphalia by Anton Wilhelm Arndts from the year 1815. In: Südwestfalenarchiv Jg. 2011 pp. 161–172.

- History of the Warsteiner Gruben- und Hüttenwerke Aktiengesellschaft. Typescript, 1938 [Presumably from Director Gustav Simon. A copy can be found in the Westfälisches Wirtschaftsarchiv Dortmund F28 / 14, the page numbering here follows the Word document and not the original for reasons of traceability], Word document available . ( Page no longer available , search in web archives )

- Wilfried Reininghaus ; Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period . Münster, 2008.

- Wilfried Reininghaus: Salt pans, mines and ironworks, trade and commerce in the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Duchy of Westphalia: Westphalia from the Electorate of Cologne from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 pp. 719–760.