Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations

The Electoral Cologne Berg orders from the first to the last from 1533 to 1669 governed the Mont property in the electorate and its by-country to the Vest Recklinghausen and the Duchy of Westphalia . Due to the importance of mining and smelting in the latter area, these regulations mainly regulated the conditions there. In some cases, although they claimed validity for the entire state, they were only tailored to certain areas. The last Bergordnung was also valid after the end of the electoral state in the area of the former duchy between 1803 and 1816 under the rule of Hesse-Darmstadt and until the decree ofGeneral Mining Act for the Prussian States from 1865/68 also continued in Prussian times .

Lore and Research

| year | title | Decree by | comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1533 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Hermann von Wied | |

| 1534 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Hermann von Wied | |

| 1549 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Adolf III. from Schaumburg | |

| 1557 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Anton von Schaumburg | |

| 1559 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Gebhard von Mansfeld | |

| 1669 | Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations | Maximilian Heinrich of Bavaria |

A total of six dated mountain orders for Kurköln have come down to us. The tradition is problematic. Important original sources were lost when the building of the Bonn Higher Mining Office was destroyed during the Second World War . Since only individual mountain orders appeared in print at the time, later publications have to be used in some cases. Sometimes originals still appear in archives that close these gaps in the tradition or can be used for comparison with printed versions.

This is the case with the Bergordnung from 1549, of which no contemporary copy exists. A copy from the 17th century was found in the archive of the Arnsberger Heimatbund , which is now kept in the Arnsberg town and country archives.

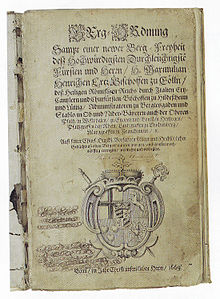

Similarly, a copy of the last Bergordnung from 1669 by the authoritative editor Christoph Frantze was found in the archives of the Melschede Castle of the Barons von Wrede . It is a carefully executed manuscript , which is provided with a decree by Elector Maximilian Heinrich of Bavaria . He himself signed the mandate, which was certified with an oblate seal. The title can be found on an endpaper:

"Original mountain regulations, according to all of the depressed copies."

The mountain order itself occupies 247 counted leaves. At the end there is a hand-drawn electoral coat of arms with a monogram . This find allows a comparison with the version printed by Hermann Brassert in his collection of mountain regulations for the Prussian lands. Various mountain orders are printed in the collection of laws by Johann Joseph Scotti .

Online source editions in the form of regesta and digital copies (Scotti, Brassert) mean that the mountain orders that have been handed down can also be viewed on the Internet. The scientific research of the mountain regulations has made significant progress over the last few years through several essays and a detailed treatment in a handbook-like monographic work.

scope

The area of application of the Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations was the actual electoral state on the Rhine and its neighboring countries Vest Recklinghausen and the Duchy of Westphalia. Since there was hardly any mining in the electoral state apart from copper mining near Rheinbreitbach , the regulations mainly applied to the coal and steel industry of the Duchy of Westphalia. Significantly, the first Mountain Regulations were not issued in Bonn , but at Arnsberg Castle . Although the mountain ordinances for the "Kurkölnischen Lande" had been issued, the ordinances were issued until 1559 due to certain local reasons and their validity may also have been limited. It should also be noted that the mountain orders are normative writings. They reflect a target state and not necessarily the reality of regional mining.

Mountain order from 1533

Older research (Brassert / Scotti) assumed that the first known mountain order from 1533 must have had earlier predecessors. Scotti adopts a mountain order from the beginning of the 15th century. Today this is rather doubted. It refers to a mountain trial from 1482, which the Lords of Neheim had led against the sovereign. The archbishop relied on the golden bull and thus on imperial law . This would not have been necessary if there had already been a separate mountain regime at that time.

Though not a mountain order properly so there was a 1530 with the awarding Erbstollengerechtigkeit to a group of trades on heritage stone at Endorf by Elector Hermann von Wied approaches to design of a mountain right.

The first Bergordnung from 1533 still referred strongly to the Erbstollen at Erbenstein, but had been significantly expanded compared to the document from 1530. The order consisted of 32 articles. The regulations on the size of the mine fields were new . In doing so, she was guided by models from other areas. Bassert describes it as a colorfully composed text with gaps in important areas without any internal connection. A codification of the entire mining law could therefore not yet be spoken of, rather it was primarily a matter of providing the mining master mentioned at the beginning with basic instructions. In addition, regional customary law shines through in many places .

What was new was that the mountain administration began to separate itself from the forest administration . Whereas in 1530 a mountain bailiff and the wood forester were named as responsible for mining, the mining regulations now provided for the appointment of a mountain master .

"If necessary, a berchmeister is deployed to and from dy berge."

"The miner has authority to lend (lend) all old and new (rough) pits."

The tendency towards writing also pointed in the direction of a mountain administration. The mountain clerk had to enter the granting of pits in a mountain book (§ 3). Changes of ownership also had to be registered there for a fee (§ 4).

In paragraphs 5 to 7 the size of pit fields was determined. The miner was responsible for measuring the pits (§ 8). The direct reference to the Erbenstein but also the further validity of the order become clear in § 9, which dealt with the duties of the ninth.

"The Erbstollen at the Erbenstein or in other places, regardless of the metal, should give up the ninth hundredweight (borren den nunden zyntener es sy was metaell is wyll)."

The miners enjoyed considerable discounts. In return for compensation, they were allowed to create their own paths across fields (Section 10).

"All mine operators should have strict sygerheit and fryness, uiß, in and off the mountain to ryten, gaen and staen."

Bergschreiber and Bergmeister were still the only electoral miners at that time. There were still no mountain judges of their own. The mountain master took on this task together with selected mountain jury members (§ 22, 28, 31). He also had the power to punish the smelting works to prevent theft (Section 12). In the event of violence, the mountain master was allowed to have the culprit captured and punish him and his body (§ 13). Similarly also § 14:

"The miner can punish anyone who deliberately suggests another uf fryness, so that peace and unity in the mine can be maintained."

In addition to the miners in the narrower sense, the first mining regulations already provided for provisions for other groups of people associated with mining. This applied, for example, to the supply of charcoal .

“Everyone who brings wood and (wood) coal to the mine should also enjoy the aingezaichneter fryheyt. The mountain master should help them to get their payment. "

It is noteworthy that the places where the persons covered by mining law lived were limited (§ 15) legal districts, which were designated as freedoms (§ 14).

In § 16 it was regulated that mine cutting work could only be carried out by persons whose suitability had been checked by the miner beforehand. In the event of a dispute about advances (publishers), the miner had to decide (§ 17). If a debtor escaped, his property could be attached by the plaintiff or the publisher (Section 18). The publishers are another group of people associated with mining.

Above all, financial privileges should make mining and smelting attractive to investors. Extracted lead or other metals as well as supplies for mining should be duty-free (§ 19). The next point is even clearer:

“The archbishop assures all trades, servants, merchants or others protection of life and property. If they build houses, mills or smelters that serve the mine or the pits, they should be exempt from depreciation, appraisal and bondage (both appraisal and indulgence) as long as the mine is in operation. "

This means that the miners and people who invested in the necessary building facilities were exempt from compulsory labor and all taxes.

The not yet fully completed separation from general law is shown by the fact that the mountain jury was determined partly on the basis of mining law and partly on the basis of land law (Section 21). The following provision (§ 22) regulates the costs of the mining court proceedings and stipulates that the loser of the process also had to bear the costs of the other side. In § 28 the archbishop reserves his mountain court (“gerychte zum berchwerk”) and authorizes the mountain master to pronounce penalties. In order to avoid costs, everyone should represent their own cause there, spiritual lawyers (“no speaking, who geystlych is”) were prohibited.

The sovereign made a profit from mining in particular from the mining tithe to be paid . The written form also applied to its collection:

"The miner is supposed to collect the tithe, keep records about it (with flyß offschryven, wais dy work gyt) and mark all the confiscated items."

The working hours were regulated in § 24:

"You should drive in every morning at seven o'clock and work until eleven, come back in the afternoon at one o'clock and work until five o'clock after the hoitman knows."

If necessary, the mountain master should provide provisions from Bergbuch d. H. Read out the Mountain Regulations (§ 25).

Mining enthusiasts, regardless of whether from abroad or inland, had to start construction within fourteen days after they had applied for a mortgage, otherwise the permit would expire (“fall outside”) (Section 26). Trades that did not dismantle against the majority decision of their co-trades should lose their shares after a period of three days (§ 27).

Specifications have also been made on the freedom of movement for wage-dependent workers.

“Sergeants and miners should protect the land from harm. You are allowed to go in and out with sunneschyn. If they move on after eight days, sooner or later, they should be paid the appropriate wages for a week of work. "

The mountain master and the jury had to take a special oath (§ 31). State officials and officials who violated the mining regulations had to expect severe penalties (Section 32)

Mountain orders from 1534 to 1559

Since the mountain orders of 1534, 1549 and 1559 are the same, they are considered here collectively. This also includes another undated mountain order, which, however, probably dates from the middle of the 17th century. Its content largely corresponds to that of 1549, relating to silver finds on the Breitenhardt. It was waived because it was assumed that there were larger deposits there.

It is uncertain whether the first mountain order from 1533 actually came into force, as a new mountain order was issued only a few months later in 1534. There is no justification for the rapid succession. Brassert speculated with little credibility that the upswing in mining that had meanwhile occurred would have made a new, more detailed order necessary. This mountain order is also not yet complete in comparison with similar orders in other regions, but the particularities of state law have been overcome by using Saxon and Bohemian models. There are similarities up to and including formulations with the ducal Saxon mountain order from 1509. There are also similarities with the later mountain order for Nassau - Katzenelnbogen from 1559. Wilfried Reininghaus also sees clear similarities to Saxony . However, the mountain order of the Electorate of Cologne did not copy the systematic model. The proximity to the Saxon order becomes clear in the adoption of the terminology among other things Kux or Zechen .

Differences between the version of 1534 and that of 1549 were possibly in the introductory narrative . There is talk of the desire of trades to issue a mountain code. The concrete background could have been the mining activities of Arnold von Kempen at that time on Erbenstein.

Compared to 1533, the level of detail in the mountain regulations has increased. The text now consisted of 44 articles. Activities such as grooming, prospecting or lending were described more clearly than before. It was also structured more systematically and regulated new issues.

In § 1, the special legal district established for mining was established, in which state officials were not allowed to intervene. The order then went into the search for ores and the granting of authorizations (§§ 2 to 8). Searching for ores was permitted everywhere with the exception of houses ("disch, bethstatt and fewerstett," § 4).

In § 9 and in other places (§ 14 and 23) the relationship between cities and mountain freedoms is dealt with at least indirectly and a distinction is made between the two. The creation of hereditary tunnels is made dependent on the sovereign permit (§ 10). The provisions on penalties (§§ 12 to 14) have been added.

The rights of the trades were clarified (§§ 15 to 24). The wording suggests that a considerable number of the trades did not come from the Duchy of Westphalia itself. They were dependent on administrators and factors. All those who come to the country for mining are escorted by the sovereign. Immigrant miners were under sovereign protection (Section 35). They were also assured of freedom of movement:

"Everyone who comes to the mine with their household (s) enjoys free entry and exit."

Own articles dealt with the huts (§§ 25 to 27) or the factors (§§ 28 and 29). Various economic policy and legal aspects followed in the next twelve articles. Among them was the electoral right of first refusal for silver (§ 33). Upon revocation and upon payment, the trades could remove timber from the sovereign forests (§ 34).

It is clear that for the further influx of miners, their privileges were increased. They were now withdrawn from the power of the drosten and officials. They were only subject to the miner's court (§ 38). Internal disputes outside the mine itself could be resolved by the miners. To this end, they could choose judges and juries from among themselves (Section 39). This court of miners stood next to that of the miner, who himself was responsible for all legal disputes in the mine (Sections 28 to 32). The special dishes of the miners can be considered the basis of the mountain freedoms of Silbach and Endorf that emerged in the course of the 17th century .

The undated order from the middle of the 16th century, which essentially corresponds to the text of the Bergordnung of 1549, was based on notable finds not only of copper, but also of precious metals such as gold and silver (§ 56). The production of coins (§ 54) and the delivery of the silver to an electoral silver chamber (§ 36) were regulated. In these provisions the fiscal interest of the Elector was particularly clearly expressed.

The mining regulations issued by Anton von Schaumburg in 1557 have not been preserved, but have probably not been updated. At the same time as the Bergordnung, an electoral patent appeared in 1557 for the appointment of a mountain bailiff and a mountain master for the Duchy of Westphalia. The mountain regulations of 1549 and 1557 were therefore only new mountain regulations in name. In fact, they were essentially repeated publications of the 1534 order.

Mountain order from 1559

The privileges granted so far were not enough for the miners. They demanded similar extensive rights as existed in some other territories. In a petition, trades from mines “uff dem sylberge im Grund sydlingkhausen assingkhusen elpe and ramsbecke” turned to the sovereign in early September 1558. In eight articles they essentially demanded: the unrestricted construction of paths to the mining, stamping and smelting works, the use of water gradients, free construction and coal wood, exemption of the trades from public taxes, decree of the tithing for ten years, interest and duty-free sales of metals both at home and abroad, permission to have a free weekly market and free commercial operation in the mines, free and safe access and roads to them, employment of competent officials and completely free disposal of mine assets. The request was directed not only to the Elector Gebhard von Mansfeld , but also to his brother, Count Hans Georg zu Mansfeld and Helderungen, because he was considered to be a “lover and sponsor of the Bergkwerge”.

The elector responded to the request and had proposals drawn up to promote mining. The granting of mountain freedoms based on the Saxon and Bohemian model and a mountain regime that was also based on Saxony and Bohemia was deemed necessary. In fact, in June 1559 a mountain freedom was proclaimed, which endows mining with considerable privileges. Shortly afterwards, new mountain regulations were also issued. Both documents were printed in Cologne. Copies of Berg Freiheit were also sent to other territories, probably to promote investments in the Duchy of Westphalia.

Basically two reasons were given as reasons for the enactment of a new mining regulation. On the one hand, the previous mining regulations got into disorder over time and, on the other hand, the war - probably meant the Schmalkaldic War - would also have had negative effects on mining matters.

"During the arduous wars and wars and favors, times dwindled and their part was withdrawn. A few years ago, many trades were withdrawn (have become disgusted and revolted)."

A mine should not be withdrawn from any trade in war and peace. Mountain debts, additional penalties and hut meals must, however, be paid. Confiscations by the sovereign should be avoided in future (§ 1). Despite the complaints about the time situation, there has been a considerable expansion of the mining industry. In particular, the influx of external capital had indicated the need for regulation.

According to Brassert, the mining regulations were based almost entirely on the Saxon mining law and partly followed the mountain regulations of August von Sachsen from 1554. This went so far that areas such as tin mining , which played no role in the Sauerland, were included. The more recent research judges this more cautiously. For them, too, the orientation towards external models is out of the question, although special regional aspects have also been incorporated. This includes, among other things, the determination to be a Jew :

“It is to be learned that such ertz and silver are supposed to be pushed under and bought up by them and shipped out of our countries to the Jews who make their practice in our country. Innkeepers [in mining towns] who host Jews should warn them. "

The mention that there had been a lot of controversy about the Erbstollen and the detailed regulation of this aspect resulting from it (§ 82), refers to regional problems.

In terms of content, the regulation of the (financial) conditions of the trades on site and the publishers, which were often external, was significant. So the publishers and not the trades had to pay the extra fee (§ 63) If the publishers tried to settle the workers with goods instead of money, this should be investigated and punished by the miner (§ 64). A three-shift operation was planned.

“The first shift arrives early at four o'clock, the second at 12 noon, and the third at 8 o'clock in the evening. Everyone should stay eight hours on the shift and not drive from the site before the Steiger knocks out. Steiger and shift supervisors shouldn't keep rent boys and servants who carry the beer or hire relatives to please the other. Locals should get work from foreign miners. "

Night shifts were prohibited where three shifts were not carried out. (Section 75) In addition to promoting the operation of the mines, the mining regulations were also concerned with protecting miners, so double shifts were prohibited. In the meantime, social-disciplinary tendencies cannot be overlooked.

"The good Monday and the beer shifts will be abolished with a heavy penalty for violations."

Another tendency was the significant expansion of the regulations on smelting operations. While the Bergordnung of 1549 managed with just a few articles, there were now sixteen paragraphs. This quantitative expansion reflects the meanwhile increased number of huts. Hut riders should visit and check the operating facilities on a daily basis (Section 12). Apparently there was competition for qualified specialists. Smelters were not allowed to be lured away during the smelting process (Section 97). A separate arbitration system was introduced for the ironworkers (Section 89). Written form in smelting operations and the stipulation that smelting was only allowed to take place in certain smelters were state control measures, especially with a view to the extraction of silver. The hammer mills were not included in the mining regulations . This did not happen until 1669.

It was planned to set up a mountain administration with strong personnel.

“A chief captain, a chief miner and a mountain bailiff are appointed in place of the sovereign, and in each mining town, depending on the size of the mines, a miner, jury, tithe, dispenser, counter-writer, hut rider, tester, silver burner and mark separator. Shift supervisors and steers are not allowed to leave the mines without the permission of the mining officials. "

This large number of mountain officials was a takeover of the Saxon model. This did not exist in the reality of mining in the Sauerland. (§ 3)

Mountain order from 1669

In 1668, the miner Engelhardt submitted a worrying report on the state of the mining industry in the Duchy of Westphalia. Many mines had fallen into disrepair as a result of the Thirty Years' War , and due to an acute lack of money there was hardly any willingness to invest in mining. In addition to other proposals, Engelhardt suggested revising the 1559 mining regulations and having them printed, as there were hardly any mining regulations in circulation.

After Engelhardt's death and the appointment of Christoph Frantze as mountain master, he worked out a new mining regime. The mountain order of 1669 was also based on existing models. The closeness to a book by Georg Engelhard von Löhneysen is particularly clear : Report from the Bergkwerck ... from 1617. Towards the end of the 18th century, the Bergordnung was even almost a copy of Löhneyß's book. But already Brassert pointed out in the 19th century that there were clear deviations and regional references in the mountain order and that this therefore had an independent value. So the order for the Olper Breitschmiedezunft was such a regional aspect. The historian Horst Conrad even judges that the Bergordnung of 1669 was one of the "most important mining regulations of the time" despite the recourse to models.

The main goal of the new mountain order was to overcome the crisis in the coal and steel industry as a result of the Thirty Years' War. However, the complaints about the course of war and times are taken almost verbatim from the 1559 order. A big difference to the earlier orders was the systematic structure. The text was now divided into fourteen parts, each with up to 37 articles. The text volume was also considerable. In the press at Brassert, the Bergordnung from 1669 was over 150 pages long.

The first part, General Provisions for All Mines, was new except for the first article. Among other things, it appealed to unity and peace among the miners. Value was placed on a decent life in the mines and smelters by banning fights (§§ 5-6).

The second part was about the mining officials and mining towns. Again, a large number of mountain officials are mentioned. As in 1559, this only reflects a target state, not the actual state. What was new here was the mention of miners' elders and thus the regulation of social benefits (§§ 11–13). The Bergordnung contained an ordinance to combat misery. Thereafter, disabled miners, widows and orphans received grace money. This could be paid out once or as ongoing support. However, these regulations do not appear to have entered into force. The privileges of the mining towns were confirmed (§ 14). The regulations on Jews, who were now almost completely excluded from the mining and mining industry, were significantly tightened (§ 16).

The third part of the mining regulations dealt with the mining operation itself. Much more space was given in parts four and five to mine separation and the surveying of the pits.

The same applies to the determination of the hereditary tunnels (part 6). Part seven, entitled Shift Supervisor, Steiger , Worker, dealt extensively with those employed in the mining industry. In doing so, both social disciplinary aspects and caring provisions can be identified. The working hours, which corresponded to a twelve-hour day, were regulated, as were the employees' breaks. There was sick pay and an accident pension. As in the Bergordnung of 1559, action was taken against beer layers and the Blue Monday.

In the eighth part, which was essentially about the additional fines, provisions were also made on the remuneration of the miners. In part nine, provisions were made on stamp mills and smelters. The tenth part was devoted to coinage. Part eleven was about cuts, remuneration, accounting.

The twelfth part was headed the Eisenstein order. These special provisions for the iron stone can be explained by the fact that the previous articles mainly focused on the “nobler metals” (copper, lead and silver). For this reason, provisions on payment in iron stone mining are also included here. A ban on paying workers not with money but with goods ( truck system ) was also issued. The miners in iron stone mines were exempt from being drawn into the military.

The thirteenth part dealt with the ironworks and for the first time also with the ironworks. One starting point was the critical sales situation. Therefore, minimum prices for domestic and foreign sales of iron were introduced. The purchase of iron ore from abroad was completely prohibited. The woodcutters and the production of charcoal were also included in this part. The freedom of movement for miners, smiths and hammer smiths was severely restricted by the ban on migrating abroad. In addition, the wages of those employed in iron and steel works were also set. A special aspect was the regulations for the Breitschmiedezunft in Olpe. The last part was dedicated to the mountain process. This did not differ significantly from the Bergordnung of 1559.

According to Conrad, different tendencies emerge in the mountain order of 1669. The growing centralism took into account the absolutist aspirations of the electors. The entire staff was now subordinate to the Privy Council and the Mining Captain in Bonn. The Mining Captain had a ministerial position. He was directly subordinate to the sovereign. His judicial powers in mining matters were extensive. Subordinate to him and thus factually mediated were the judges of the mountain freedom. There was also a trend towards professionalization. In this context, a further expansion of the written form is also necessary. The mountain clerk now had to keep five different mountain books. With regard to employees, welfare and social discipline went hand in hand. Reinighaus emphasizes that the mountain order of 1669 was strongly influenced by mercantilist ideas. The authority's claim to regulation was particularly evident in the fact that the mining authority received extensive competencies. Its implementation therefore met with resistance, so that as early as 1679 Frantze asked to be allowed to revise the mining regulations again. It didn't come to that.

Contrary to what Conrad claimed, the Bergordnung was copied by a printer in Bonn shortly after it was published. It seems to have been widespread among the trades. This is indicated by a preserved specimen owned by the Hövener family in Brilon . The volume probably comes from the estate of the Kannegießer family. Nevertheless, there were complaints that little was known among the trades. Hence a new pressure was suggested which for various reasons did not materialize. An unofficial reprint took place only in 1746.

After the Bergordnung (Bergordnung) was published in 1669, various edicts were issued which, on the one hand, affirmed the mercantilist spirit of the Bergordnung, but also made it clear that those affected often did not adhere to the regulations. In particular, the ban on importing foreign ores and iron was seen as a threat to the hammer and smelting works. Because the companies on the Diemel and the Hoppecke were dependent on imports because of insufficient ore from their own mines, they did not adhere to the ban and instead claimed that their hammer mills were across the border and were therefore not subject to the ban.

Further development of mining law in the Electorate of Cologne

Up until the end of the electoral state there was no longer a general revision of the Bergordnung of 1669. Only special ordinances were issued, the validity of which was essentially limited to the Duchy of Westphalia. There were ordinances on the jurisdiction of the mining offices and the court train (1676, 1679, 1739, 1743), on the exemption of miners, smelter and hammer workers as well as the mining officials and unions (1679, 1760) via the broadsmiths' guild in Olpe, Drolshagen and Wenden (1672, 1781, 1788), on the duty-free export of iron and minerals (1678), on the ban on iron imports (1678), on the prohibition of Jews trading in iron, copper, etc. (July 1678, December 1678, 1768 ), on the partial or total ban on the export of charcoal (1679, 1746, 1747, 1768, 1769).

After the right bank of the Electorate of Cologne fell to France as a result of the First Coalition War in 1794 , French mining legislation was introduced there. This remained in force even after the transition to Prussia in 1815 until the General Prussian Mining Act of 1865 was passed. In the parts of the electoral state on the left bank of the Rhine, the Bergordnung continued to apply as a particular law from 1669 until the aforementioned general Prussian law was passed . However, since this area fell to different sovereigns from 1803 to 1815/16, mining law did not develop uniformly during this period. During this time, various ordinances were issued, in particular from Hessen-Darmstadt for the Duchy of Westphalia on mining. With the accession of all areas of the former electoral state to Prussia, this different legislation ended. However, until 1865 there was no generally applicable subsidiar law on the left bank of the Rhine . The general Prussian land law was only valid in Vest Recklinghausen and the Duchy of Westphalia, but not in the other areas where the common German mining law had to be used.

With the general mining law for the Prussian states of 1865/68, the mining regulations of 1669 lost their validity. A curiosity is likely to be that the Federal Court of Justice in 2006 used the Electoral Cologne Mountain Regulations to determine the term marble.

swell

- Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian country. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, ( digitized version ).

- Johann Josef Scotti: Collection of the laws and ordinances that were passed in the former Electorate of Cologne (in the Rhenish Archbishopric of Cologne, in the Duchy of Westphalia and in the Veste Recklinghausen) on matters of state sovereignty, constitution, administration and administration of justice. From 1463 to the entry of the Royal Prussian governments in 1816. Düsseldorf 1830/31 ( digitized version ):

- Montanwesen Duchy of Westphalia, selected regesta in full text.

literature

- Horst Conrad: The mountain order of the Electorate of Cologne in 1669 and its surroundings. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996, pp. 153-171.

- Wilfried Reininghaus: The Bergordnung of the Cologne Archbishop Adolf III. von Schaumburg for the Duchy of Westphalia 1549. Introduction and Regest . In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2/2002, pp. 77–84.

- Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008.

Individual evidence

- ↑ compiled from: Hermann Brassert: Berg-Ordnungs der Prussischen Lande. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858., pp. 517-521.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The Bergordnung of the Archbishop of Cologne Adolf III. von Schaumburg for the Duchy of Westphalia 1549. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2/2002, p. 77.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg. 1996, p. 153.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 518.

- ^ Mining Duchy of Westphalia. Selected regesta in full text .

- ^ Scotti - Kurköln (Duchy of Westphalia, Vest Recklinghausen) (1461-1816) .

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858 ( digitized ).

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 517.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The Bergordnung of the Archbishop of Cologne Adolf III. von Schaumburg for the Duchy of Westphalia in 1549. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2/2002, p. 79, Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 76 f.

- ^ Johann Josef Scotti: Collection of laws and ordinances which were passed in the former Electorate of Cologne (...) on matters of sovereignty, constitution, administration and administration of justice. From the year 1463 until the entry of the Royal Prussian governments in 1816. Vol. 1. Düsseldorf 1830, p. 37.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 518.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996, p. 164.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 75 ( Regest around 1530 Hermann V. von Wied, Archbishop of Cologne and Elector, privileged 16 trades with inheritance rights at Erbenstein in the parish of Stockum because of the dewatering problems ).

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 518.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 75 f. (Hermann V. von Wied, Archbishop of Cologne, Duke of Westphalia and Engern and administrator of the Paderborn Monastery, Elector, issues a mining order for the Erbenstein near Endorf and all other mines in his territories Regest 1533-09-04 ).

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The Bergordnung of the Archbishop of Cologne Adolf III. von Schaumburg for the Duchy of Westphalia 1549. Introduction and Regest. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2/2002, p. 77.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 519, Hermann V. von Wied, Archbishop of Cologne and Elector, issues a mountain order for his territories Regest 1534-01-31 .

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The Bergordnung of the Archbishop of Cologne Adolf III. von Schaumburg for the Duchy of Westphalia in 1549. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2/2002, p. 78.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus: The Bergordnung of the Archbishop of Cologne Adolf III. von Schaumburg for the Duchy of Westphalia in 1549. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2/2002, p. 78, Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 76.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 76, Wilfried Reininghaus: The Bergordnung of Cologne Archbishop Adolf III. von Schaumburg for the Duchy of Westphalia 1549. In: Südwestfalenarchiv 2/2002, p. 79.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 76 f.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 77, Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 519.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 520.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 520.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 521.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 81.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 81 f. (Johann Gebhard, Archbishop of Cologne and Elector, issues a mountain order for his territories Regest 1559-06-24 ).

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996, p. 154.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 522.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996, p. 160.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 91.

- ^ Matthias Kaever: The social conditions in coal mining in the Aachen and South Limburg districts. Münster, 2006, p. 175.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 91 f.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996, pp. 160-162.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996, p. 158.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 93.

- ↑ Horst Conrad: The electoral mountain order of the year 1669 and its environment. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996, p. 158, Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 93.

- ^ Wilfried Reininghaus, Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster 2008, p. 93 (Maximilian Heinrich, Archbishop of Cologne and Elector, issues a new mountain order for his territories Regest 1669-01-04 .)

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 524.

- ^ Hermann Brassert: Mountain orders of the Prussian lands. Collection of the mining regulations valid in Prussia, together with additions, explanations and decisions of the higher tribunal. Cologne 1858, p. 525.

- ^ Ingo von Münch: Legal policy and legal culture: Comments on the state of the Federal Republic of Germany. Berlin, 2011 p. 42.