County of Arnsberg

The county of Arnsberg was created in the 11th century when the Counts of Werl moved to Arnsberg . At this point in time, they had largely lost their extensive domain, which at times stretched from the North Sea to the Sauerland . Even when the focus of the county was shifted to Arnsberg, the history of the territory was marked by the threat to neighboring strong territories (especially Grafschaft Mark , Archdiocese of Cologne ) and had to accept considerable loss of territory in some cases. Instead of a policy of expansion to the outside world, the counts pursued a systematic policy of land development and territorialization . When it became clear that Count Gottfried IV would remain childless and other succession arrangements could not be made, he sold the county in 1368 to the Archbishopric of Cologne . The area of the County of Arnsberg rounded off the territory of the Cologne Duchy of Westphalia and became its center.

Political history

Counts of Werl-Arnsberg

Arnsberg was owned by the Counts of Werl . A prerequisite for the relocation of the main focus of power from Werl to Arnsberg was the construction of a castle . The first castle near Arnsberg was the so-called Alte Burg or Rüdenburg , built around 1050/65 by Count Bernhard II von Werl . The new castle, built around 1080 under Count Konrad II , became more important and later became Arnsberg Castle . Conrad probably already shifted the focus of his rule from Werl to Arnsberg . This change only came to a complete conclusion under his successor.

After Konrad's death, the county passed to his sons Heinrich and Friedrich . Friedrich was dominant. This carried the title of count and ruled from Arnsberg now. The brother Heinrich was resigned to the county of Rietberg . One of Konrad's other heirs - Luitpold - sold his share of the territory to the Archbishop of Cologne .

Friedrich saw himself forced to renounce the policy of his ancestors, which extended to Friesland, and to concentrate on securing his rights in his core area. There they were potentially threatened by the Archbishops of Cologne and Lothar von Süpplingenburg read the Duke of Saxony. Beyond the narrower area of his county, Friedrich was important because he played a considerable role in the politics of the empire and exerted influence on the contemporary emperors. However, if necessary, he changed sides and used the competing forces of the Emperor, the Archbishops of Cologne and the Duke of Saxony in the region for his goals.

Like his father, he was on the side of the emperors in the ongoing dispute with the reform papacy (which may have contributed to his negative assessment by spiritual chroniclers.)

In 1102 it was probably in this context that the count invaded the territory of the Archbishop of Cologne Friedrich I. In return, the bishop invaded the county and destroyed the Arnsberg Castle. The bishop's troops were then defeated by Friedrich and some of them were taken prisoner.

To resolve the conflict, Friedrich was forced to cede about half of his territory to the Archbishop. In this context, the archbishop also acquired Hachen Castle and thus had a base in the immediate vicinity of Arnsberg. The Arnsberg Castle was rebuilt and below it a settlement was formed, from which the town of Arnsberg emerged.

In the conflict between the later Emperor Heinrich V and his father Heinrich IV , Friedrich, in contrast to large parts of the nobility, was on the father's side. In this context he attacked Bishop Burchard von Munster , who was on the side of the son, captured him in 1106 and handed him over to the emperor.

For this reason, the relationship with the new ruler was not unclouded after the death of Henry IV. Therefore, not the count, but his brother Heinrich accompany Emperor Heinrich V on his imperial train to Italy. In 1111, Heinrich was one of the hostages taken by the Germans during negotiations with Pope Paschal II .

In 1112 Friedrich visited the emperor's camp in Münster and swore his allegiance to it. Of course, this agreement did not last long. Friedrich and his brother Heinrich belonged to the Saxon aristocrats in 1114 who revolted against the emperor and switched to Lothar von Süpplingenburg's side. When he and his troops stabbed the imperial units in the rear during the battle of Jülich , he made a decisive contribution to their defeat. The imperial troops then raided the county, but could not decisively weaken Friedrich, who continued to play an important role in the indignation of the nobility.

After negotiations with high-ranking imperial emissaries, Friedrich swore allegiance to the emperor again in 1115. In fact, the count has been in the emperor's service since then - for example in the armed conflict over the occupation of the bishopric of Osnabrück . In 1120 Friedrich was one of the mediators between the emperor and the rebel princes. In gratitude for his services he was given the right to dispute between the Rhine and the Weser for himself and his descendants in 1118 .

If Friedrich was involved in the conflicts of the empire in previous years, he now had to take care of the area of his rule himself. So he tried in vain to prevent the Count von Berg from founding Altena Castle . His violent attempt to prevent the Cappenberg Castle from being converted into a Premonstratensian monastery was also in vain . The founder of the Cappenberg Monastery, Gottfried von Cappenberg , married the Arnsberg heir daughter Jutta / Ida. Both entered the Premonstratensian order. After Gottfried's death, Ida / Jutta returned to worldly life and married Gottfried von Cuyk from an important noble family from the Lower Rhine.

Friedrich was one of the most important rulers of the county, but he also overstepped its forces and thus contributed to its loss of importance in the long term.

The cession of a large part of the county to the elector of Cologne turned out to be disadvantageous, as this area became the starting point for the expansion of Cologne in Westphalia in the next centuries (at the expense of the county of Arnsberg in particular).

Counts of Cuyk-Arnsberg

After the death of Friedrich, the old line of the former Counts of Werl died out. The county fell to the husband of the daughter Jutta / Ida from the family of the Lords of Cuyk . As Gottfried I, he left hardly any traces in the county and probably concentrated primarily on his Dutch possessions.

He was succeeded by Heinrich I. In the first years of his reign, he too often stayed at the side of the emperors, but also in the vicinity of Archbishop Rainald von Dassel and his relative Heinrich the Lion . However, with the murder of his brother, he fell out of favor with the princes. Archbishop and Henry the Lion (in his capacity as Duke of Saxony ) appeared as avengers. Other bishops of Westphalia joined them. Together they besieged Arnsberg in 1166 and conquered and destroyed the castle. The count escaped. When he was about to be banished, Friedrich I intervened and prevented the execution of the sentence. However, Friedrich is said to have assigned the county to a fiefdom to Archbishop Rainald von Dassel from Cologne, and Heinrich is said to have been reinstated by him in his sovereign rights.

One of the positive consequences of the murder for the region was the establishment of the Premonstratensian Monastery in Wedinghausen around 1170. According to tradition, the establishment was viewed as an act of atonement. However, there are no references to this in the sources. At the end of his life, the count entered the monastery as a lay brother and died there on June 4, 1200.

During Heinrich's time, developments that were detrimental to the future development of the county occurred. As a result of the conflict with Frederick I, Henry the Lion lost the Duchy of Saxony. As the Duchy of Westphalia , parts of it fell to the Archbishopric of Cologne. This increased the pressure of the archdiocese on the county of Arnsberg in the medium term.

The Archbishops of Cologne began to systematically expand their position in Westphalia and the county of Arnsberg was soon surrounded by Cologne territory almost everywhere. Especially in the 13th century, the bishops built numerous fortified cities and castles in their area. The county was also beset by the rising Counts of the Mark .

Count Gottfried II came to power in 1185 while his father was still alive. Co-regent was temporarily his older brother Heinrich II. Right at the beginning of his rule, his troops defeated five neighboring counts in a battle near Neheim . During his time the systematic development of territorial rule began.

Like his father, Gottfried III also ruled . almost five decades. This continued the consolidation policy. Shortly after assuming his rule, after family disputes in 1237, the count was forced to cede the area around Rietberg as the County of Rietberg to a relative. This undoubtedly weakened the county of Arnsberg, but this was the last significant cession of territory until the end of this territory. In the years to come, inheritance divisions were avoided as a rule, that later-born sons were settled with spiritual benefices.

Gottfried also felt the power of the archbishop when he had to humble himself after a feud before him. However, the relationship with the Erzstuhl relaxed noticeably in the following years. This even went so far that Count Gottfried supported the bishop in military conflicts.

In particular, this relatively good relationship enabled the Arnsberg counts to pursue a policy of internal development. With the election of Count Siegfried II of Westerburg as Archbishop, this changed again. Count Gottfried belonged to an ultimately futile alliance of Westphalian aristocrats, bishops and the Landgrave of Hesse to break the influence of Cologne in Westphalia. In the following years of his reign, Gottfried presumably did not undertake any further military actions. Instead, he founded the Cistercian convent Himmelpforten in the Möhnetal in 1246 .

Count Ludwig also ruled the county for over 40 years. Internally, he continued the expansion and consolidation of the dominion. The villages of Sundern , Hagen and Langscheid were created through clearing, some of which were declared freedoms.

Under Count Wilhelm , the territory was once again involved in larger political contexts. In contrast to the Archbishop of Cologne, Wilhelm did not support Frederick I of Austria after the death of Emperor Henry VII , but Ludwig of Bavaria. He prevailed as Ludwig IV in this conflict. In gratitude, Count Wilhelm received an imperial fiefdom from the Kaiser: the Vogtei over Soest , ducal rights within the boundaries of his county, the so-called pre - litigation (i.e. knightly honorary right - the wearing of the imperial flag was otherwise reserved for the Duke of Swabia ) in the event that the Kaiser or the supreme duke (i.e. the archbishop of Cologne) wages war in Westphalia, as well as forests and customs revenue near Neheim. The ducal rights were of course of little practical importance in view of Cologne's factual superiority.

End of the county

Count Gottfried IV was the last count of the county, but played a far more active role than most of his predecessors. While the old count was still alive, Gottfried fell under the papal ban because he had the bishop of Munster , Ludwig II of Hesse , arrested because of his attacks on the county. He was only released from this ban shortly after the beginning of his reign. In the first years of his reign, the relationship with the Archbishop of Cologne was relatively relaxed. This even gave the count the right to fortify the city of Hirschberg . This agreement ended when Gottfried and Count Adolf II von der Mark besieged and captured the Cologne city of Menden . This conflict ended in a settlement.

In the following years the balance of power in Westphalia shifted drastically at the expense of the Arnsberg Count. After Wilhelm von Genneps took office as the new Archbishop of Cologne, an alliance between the Erzstuhl and Engelbert III came about . from the mark . While the Arnsbergers were able to navigate between the two powerful neighbors in the past, Gottfried was now isolated from the combined superiority. As a result of a feud (1352) with the Mark, the Archbishop was able to force Gottfried, among other things, to renounce the exercise of spiritual jurisdiction. In addition, he had to give up all claims to the Ardey rule as well as court rights in Schmallenberg , Körbecke and other places. Gottfried Fredeburg had to cede to Count von der Mark .

In 1357 there were again attacks by Cologne on the county of Arnsberg. In the course of the so-called "Arnsberg War", Count Gottfried probably destroyed the town of Winterberg . This argument ended without a victory for either side. At times there was even an rapprochement and the Archbishop's appointment of Count Gottfried as Marshal of Westphalia.

The situation became threatening when the Erzstuhl fell to Adolf von der Mark (1363), who after a brief reign from the same house Engelbert III. followed. Coordinated action by the two powerful neighbors against the county now threatened. In fact, there were military conflicts between Mark and Arnsberg in 1366. In the course of this, the city of Arnsberg was besieged, conquered and cremated.

The existence of the county was also threatened by the regent's childlessness. When there was no longer any hope of a biological descendant, the transfer of rule became necessary. At first Gottfried thought of a nephew from the Oldenburg family . When this and another possible successor died, the situation was open again. The house of the Counts von der Mark was out of the question for obvious reasons. At first glance, a transition to Cologne was hardly imaginable in view of the past conflicts. Nevertheless, the county was sold to the Erzstuhl. Among other things, this was due to the fact that Bishop Engelbert no longer had full power of disposal over the diocese, but was effectively disempowered by the appointment of Kuno von Falkenstein as coadjutor. Incidentally, after the bishop's death in 1367, it was not the House of Mark who benefited, but with Friedrich III. von Saar become largely a stranger to this step.

In 1368 Gottfried sold the county of Arnsberg for 30,000 guilders to the Archbishop of Cologne. Gottfried and his wife left their territory and settled in the Rhineland. After Gottfried's death, he was buried as the only secular prince in Cologne Cathedral in 1371 . For Cologne, the acquisition of the county meant that its Duchy of Westphalia, which had previously grown around the county, got a center.

Count family

Relationships and branch lines

Due to the descent from the Werler counts, the counts of Arnsberg were related to the Salians and the royal house of Burgundy . There were also family ties with Friedrich I and Lothar III.

In addition to the main line, there were a few other families that went back to the Counts of Arnsberg. These included the noblemen of Rüdenberg , who were initially based in the old castle in Arnsberg. These later acquired the Burgraviate of Stromberg and finally split up into the Stromberg, Rüthen and Arnsberg lines. Another branch line were the so-called " Black Noblemen " of Arnsberg, probably descendants of Count Friedrich, who was killed by his brother Heinrich I. This family can be traced for four generations before it went out at the end of the 13th century. For both families there is also the thesis that they were independent families. The most important branch line was that of the Counts of Rietberg .

The Counts of Arnsberg had family connections with the most important dynastical families in Westphalia and beyond. These included the Altena-Mark houses , the noblemen of Bilstein , Blieskastel , Lippe , Ravensberg , Jülich , Wittgenstein , Waldeck , Oldenburg , Mecklenburg and Kleve .

Various members of the count's house achieved considerable positions in the service of the Church. Jutta von Arnsberg was Abbess of Herford Monastery from 1146 to 1162 . Adelheid was abbess of the Meschede Monastery . Bertha became abbess of Essen Abbey in 1243 . Syradis († 1227) was abbess of St. Aegidii in Münster . Agnes von Arnsberg († 1306) was the last abbess of Meschede. Her brother Johannes († 1319) was the first provost of the newly established canon monastery in Meschede. Gottfried von Arnsberg († 1363) was Archbishop of Bremen and Hamburg. Another Jutta was Abbess von Fröndenberg. Mechthild was abbess in Böddeken and Piornette was abbess of St. Ursula in Cologne.

Feudal position

In a document of Frederick I from 1152, Count Heinrich was referred to as "princeps". The counts had various imperial fiefs , even if the sources do not show any enfeoffment by an emperor for the entire county. Research has assessed the county's legal status differently. Sometimes it was viewed as an imperial fiefdom, a fiefdom of the Archbishops of Cologne and an allod of the family. In the deed of sale to the Erzstuhl from 1368, the county was defined as an allodial property: "que omnia et singula nostra bona liberta et allodiale fuerunt, et a nemine feudali seu alio jure dependent." Only after the sale was the county assigned to the Cologne bishops Reichslehen.

However, there were already imperial feudal rights. This included in particular the right of pre-dispute between the Weser and Rhine, which has been confirmed on various occasions. The Neheim customs and bridge money were also imperial fiefs. The same applies to the Vogtei over Soest, several Gogerichte , all free counties of the county, minting rights, the Luerwald and the Wildbann. These rights were last confirmed to Gottfried IV in 1338.

There were also feudal relationships with the Archbishops of Cologne. The Hachen Castle , acquired by the Counts of Arnsberg in 1232 , which was connected to the bailiwicks of Menden , Sümmern and Eisborn , was accepted as a fiefdom by the archbishops. The Obervogtei via Kloster Grafschaft was also connected with this . Over time, Hachen Castle became the allodial property of the Counts. For the fortification rights for Hirschberg , Gottfried IV gave his allodial property there to the archbishops and received the area back as a fief. After a lost feud, Gottfried IV also had to cede Hüsten and the high court in Schmallenberg to the Cologne church in order to get these properties back as a man's fief. Further feudal relationships existed at the end of the county with the Landgraviate of Hesse and the County of Geldern .

The counts themselves had considerable allodial possessions, some of which they granted as fiefs. The Counts of Wittgenstein and the Mark as well as the noblemen of Büren , von Bilstein, von Rüdenberg, von Grafschaft and von Itter owned fiefdoms of the Arnsberg Counts.

In order to keep track of the various fiefdoms, a fiefdom register has been kept since the time of Count Ludwig. This was one of the first of its kind in Westphalia.

Sovereignty

territory

In 1237, after the cession of the County of Rietberg , the area received its final form until the end of the territory. At its core, the county of Arnsberg comprised the later districts of Arnsberg and Meschede in the Sauerland, without Schmallenberg, which belongs to Cologne. It was about 1,430 km² in size and the rivers Ruhr and Möhne ran through it. In the north it bordered the dioceses of Münster and Paderborn , east on the county of Schwalenberg (later Waldeck ), south on the Rothaargebirge and west on the county Mark . At the end of its existence (1368) the area had about 40-50,000 inhabitants.

Due to the expansion of the Archbishops of Cologne, a further expansion of the area was hardly conceivable. These gradually attracted all areas for which the Counts of Arnsberg could not prove unequivocal ownership claims. The acquisitions of the Cologne people were protected against the Arnsberg County with a network of castles and towns. Although the title of duke gave the archbishop the right to forbid the counts and other nobles from building castles and cities, he was not powerful enough to enforce this in every case. The Arnsberg counts had recognized in the second half of the 13th century at the latest that they could no longer counter the power of Cologne by force. Ultimately, all that was left was the internal expansion to maintain the position to some extent.

Displacement of competing dynasts

Until the end of the county, the counts tried to create as closed a territory as possible by buying or exchanging possessions. Because the opposing forces from the other side were too strong in the Hellweg area, the Arnsberg counts concentrated primarily on the Sauerland area. The acquisition of Hachen Castle and the rights attached to it represented the beginning of the systematic development of the country. Attempts were made to eliminate competing dynastical families. In addition, the counts tried to secure their property through castles and to enhance it by founding cities and freedoms.

The noblemen of Itter, the black noblemen of Arnsberg, the noblemen of Ardey were largely ousted within the county. Large parts of the Rüdenberger's property also came to the counts.

Gottfried IV. Was probably transferred from the last nobleman of Bilstein Fredeburg. In doing so, he extended the Arnsberg territorial policy to the vicinity of the Cologne cities of Schmallenberg and Winterberg. He also had the freedom to create Bödefeld. With the acquisition of Fredeburg, the count would also have controlled the long-distance trade route from Cologne to Meschede. Count Engelbert III. von der Mark did not accept this and after the death of the noble lord moved the Bilstein lordship as a settled fiefdom and also took hold of the land of Fredeburg.

Cities and Freedoms

The establishment and expansion of cities and freedoms served in particular for the internal expansion of the rule. This initially included the expansion of the Arnsberg castle and settlement. At first the old town and around 1238 the new town were attached to the castle settlement. At that time, the settlement also received city rights. Both settlement areas were protected by the Arnsberg city wall . More cities and freedoms followed until the end of the county. The towns included Neheim (town charter 1358) and Eversberg (1242). Hirschberg received town charter in 1308 , but against the resistance of the archbishop it was initially not possible to fortify it. Then there was Grevenstein .

While Gottfried III. Above all, the area along the Ruhr secured, his son Ludwig pushed the development of the forest area in the interior of the county by establishing so-called freedoms. These were equivalent to the cities in terms of commercial production, but did not have full city rights. It was about the use of the forests, the promotion of agriculture and later also of mining and metallurgy. It is unclear to what extent long-distance trading has already taken place. Freedoms were in 1368: Hüsten , Allendorf , Sundern, Langscheid , Hachen , Freienohl , Hagen, Bödefeld and Meschede . This made the county one of the Westphalian territories with the highest density of settlements with urban or town-like rights. Strategic considerations were always behind the founding. So Eversberg should secure the Ruhr valley in the east. At the same time, the city was supposed to open up the previously largely uninhabited area of today's Arnsberg Forest. Neheim served to control the western Ruhr and Möhne valley. Hirschberg should serve as a bastion against the Cologne cities of Warstein , Kallenhardt , Belecke and Rüthen .

In addition to security policy tasks, there is much to suggest that at least some of the start-ups had economic backgrounds. In particular, the proximity to usable ore deposits may have played a role. There were iron ore deposits near Eversberg. The founding of Hagen in a decidedly unfavorable location makes economic sense due to the rich ore deposits. This also applies to Grevenstein or Allendorf. More recent research judges that the Counts of Arnsberg most consistently paid attention to "a sovereign use of the income from agriculture and forestry, mining and metallurgy, but also from long-distance traffic" in the region. The counts drew a tenth income of 500 guilders from the mining industry in 1348.

Cities and freedoms took on different functions. Cities were used for protection, trade and sometimes administration. The freedoms were intended for the economic use of the surrounding area. Meschede had a certain special position, as the old abbey settlement had had a market for a long time. The place was one of the economic centers of the county. The other was Arnsberg. Cities and freedoms contributed as much as 25% of the county's total income.

Castle system

The count's castles also served to protect the land. In 1368 there were eight state castles . Most of them ( Arnsberg , Eversberg , Neheim, Grevenstein and Hirschberg ) were associated with a city. Hachen Castle was close to the unpaved freedom of the same name. The castles Wallenstein and Wildshausen were built without any nearby settlement.

The castles listed in the sales inventory of 1368 do not list all castles that at least temporarily served to defend the county. These included the Fredeburg , which was owned by Gottfried IV around 1348. Fredeburg Castle and Land were lost to the Counts of the Mark in 1367. Gevern Castle was fortified in 1353 against the planned settlement of Neuenrade in the Brandenburg region . This was made by Count Engelbert III. Destroyed in 1355. In addition to the state castles, there were other castles that other sexes were given as fiefs. These included, for example, Herdringen Castle or Melschede Castle . The castle Nordenau was by the noble lords of the county as vassals of Arnsberg Count as Open House applied. The Rüdenburg was located near Arnsberg. In addition to the actual castles, there were also some fortified houses.

Expansion of the count's rights

In addition to the above-mentioned measures to secure and expand the country, the counts also tried to increase their rights and income. In this context, the possession of courts is of considerable importance. The counts received numerous free counties from the empire. Some Gogerichte like those of Hövel , Wickede and Calle were also imperial fiefs. There were also goge dishes in the hands of the counts in Neheim, Hüsten, Arnsberg, Affeln and Körbecke . The Cologne part of the Gogericht Attendorn was from the 12th century in the possession of the Arnsbergers. Significant revenues were associated with the courts. Other income came from various dues and tithes.

The right to mint was also important. Mills were also an important source of money. 28 mills alone had to pay their taxes directly to the count.

Promotion of monasteries and foundations

The promotion of monasteries and monasteries in the Arnsberg area was also part of the policy for the development of the area. The monasteries and monasteries, like Meschede , Oedingen , Wedinghausen , Rumbeck and Himmelpforten, were either largely founded by the count family or, like Oelinghausen, later came under their influence. The counts promoted Wedinghausen and the associated monasteries Rumbeck and Oelinghausen. Adelheid von Arnsberg founded the Himmelpforten monastery in 1246. This, like the other monasteries, was not only a spiritual center, but also served to expand the country. The influence of the counts on the Meschede monastery had decreased somewhat by this time. This was problematic in view of the desired territorial formation, because a market settlement had formed around the monastery, which became an important traffic junction. In order to gain control over this important area, Gottfried III. the city of Eversberg. As a result, the office of abbess was again filled with a member of the count's house. At the time of Count Ludwig, the Meschede monastery was converted into a canon monastery. Although this was justified with the decline of the women's community, on the part of the counts this certainly also served to secure rule. The heads of the facility came from the ruler's family until the end of the county. In order to limit the influence of the Cologne archbishops, the counts tried to extend their patronage rights.

Integration into the Cologne Westphalia

When the County of Arnsberg was acquired, Cologne's Westphalia consisted of the Waldenburg office near Attendorn and the Marshal's Office for Westphalia . The county of Arnsberg lay between these two separate areas. It was not integrated into the Marshal's Office, but formed another part of Cologne's Westphalia. A separate bailiff was initially planned for the new area. At times there was a personal union between the Arnsberg bailiff and Marshal of Westphalia. The county remained, albeit under a different sovereign. The subdivision into offices, which is common in the rest of Cologne's Westphalia, was only slowly introduced in the county. It was only in the long term that the parts of Cologne's Westphalia became the Duchy of Westphalia . But until almost the end of the Old Kingdom , the county was not fully integrated into the duchy. In the 18th century there were customs posts on the county's borders. This was only moved to the outer borders of the duchy in 1791. The feudal law also remained different. The archbishops and electors of Cologne held the title of Count of Arnsberg and the Arnsberg eagle became part of the coat of arms of the electoral state.

coat of arms

Blazon of the coat of arms of the Counts of Arnsberg: “In red a silver eagle. On the helmet with red and silver covers a black half flight , covered with a red disk, inside the silver eagle. "

The Arnsberg eagle is one of the oldest coats of arms in Germany. It appears for the first time in 1154 on a seal of Count Heinrich I. A first color illustration is shown in the herald Gelre's book of arms from 1370. The coat of arms became part of the coat of arms of the Duchy of Westphalia after 1368. The first evidence can be found in a picture on a window of Cologne Cathedral from 1508. However, the basic color red was changed to blue in the 17th century. The count's coat of arms was from some cities and freedoms such as Arnsberg, Balve, Eversberg, Grevenstein, Hachen. Hüsten, Meschede and Neheim took over. In the city arms the eagle is shown in the colors white and blue.

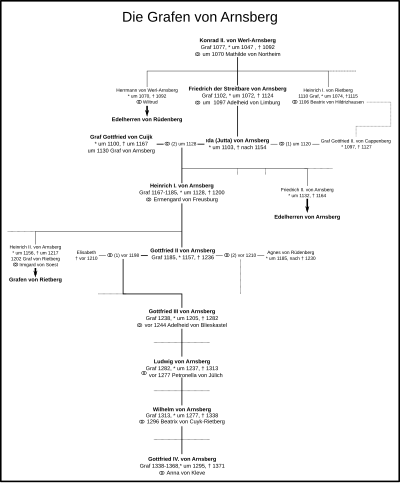

List of the Counts of Arnsberg

House Werl

- until 1092 Konrad II.

- 1102–1124 Friedrich, the controversial

House Kuik

- 1124–1154 Gottfried I.

- 1154–1185 Heinrich I, the fratricide

- 1185–1231 Gottfried II.

- 1235–1282 Gottfried III.

- 1282-1313 Ludwig

- 1313-1338 Wilhelm

- 1318–1368 Gottfried IV.

Individual evidence

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 174

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 174

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 174

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Köln, Westfalen 1180–1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Volume 1. Münster 1981, p. 174.

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 174

- ↑ Gosmann, p. 172

- ↑ Gosmann, S172

- ↑ see: Cornelia Kneppe: Castles and cities as crystallization points. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Vol. 1: The Cologne Duchy of Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster, 2009 ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 203-234

- ↑ In fact, the sales contract states a total of 130,000 guilders, but there are no invoices for the payment of 100,000 guilders, which is why neither a payment was intended nor a receipt expected. Rather, the count and countess were given castles and offices in the Rhineland in order to earn their living.

- ↑ Gosmann p. 175f.

- ↑ Quoted from Gosmann, p. 178

- ↑ Gosmann, pp. 176-178

- ↑ Gosmann, p. 180

- ↑ Gosmann pp. 179-181

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 177

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 175

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 176

- ↑ cf. Wilfried Ehbrecht: Die Grafschaft Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 176

- ^ Reinhard Köhne: Mining and territorial structures in the former county of Arnsberg. In: Mining in the Sauerland. Schmallenberg, 1996 pp. 109-111

- ↑ Wilfried Ehbrecht. quoted based on: Wilfried Reinighaus / Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 54

- ^ Wilfried Reinighaus / Reinhard Köhne: Mining, smelting and hammer works in the Duchy of Westphalia in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period. Münster, 2008 p. 54

- ↑ Gosmann, pp. 182-188

- ↑ Gosmann, pp. 188-192

- ↑ Gosmann, pp. 192-194

- ^ Wilfried Ehbrecht: The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 175f.

- ↑ Gosmann, pp. 192-194

- ^ Wilhelm Jansen: Marshal Office Westphalia - Office Waldenburg - Dominion Bilstein-Fredeburg: The emergence of the territory of the Duchy of Westphalia. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): Das Herzogtum Westfalen, Volume I, The Electoral Cologne Duchy of Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , p. 253f.

- ↑ Gosmann, p. 201

- ^ Hans Hortsmann: Cologne and Westphalia. The interaction of the national emblems. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. Regional history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 p. 212

literature

- Hermann Bollnow : The Counts of Werl. Genealogical research on the history of the 10th - 12th centuries. Diss., Greifswald 1930

- Wilfried Ehbrecht : The county of Arnsberg. Formation of rule and conception of rule until 1368. In: Cologne, Westphalia 1180 - 1980. State history between the Rhine and Weser. Vol. 1. Münster, 1981 pp. 174-179

- Michael Gosmann: The Counts of Arnsberg and their county. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Volume 1: The Electorate of Cologne Duchy of Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Aschendorff, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 171–202.

- Karl Féaux de Lacroix : History of Arnsberg. HR Stein-Verlag, Arnsberg 1895 (reprint: Stein, Werl 1983, ISBN 3-920980-05-0 ).

- Paul Leidinger : The Counts of Werl and Werl-Arnsberg (approx. 980–1124): Genealogy and aspects of their political history in the Ottonian and Salian times. In: Harm Klueting (Ed.): The Duchy of Westphalia. Volume 1: The Electorate of Cologne Duchy of Westphalia from the beginnings of Cologne rule in southern Westphalia to secularization in 1803. Aschendorff, Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-402-12827-5 , pp. 119–170.

- Johann Suibert Seibertz : State and legal history of the Duchy of Westphalia. Volume 1, 1: Diplomatic family history of the old Counts of Westphalia zu Werl and Arnsberg. Ritter, Arnsberg 1845 (online edition).