Cologne confusion

A high point in the conflict between the Catholic Church and the Prussian state in the western provinces of Prussia during the pre- March period , which led to the imprisonment of the Archbishop of Cologne in 1837, is called the Cologne turmoil or Cologne event .

The integration of the parts of the dissolved ecclesiastical principalities of Cologne , Paderborn and Münster , which became Prussian in 1815 , led to tensions between the Catholic Church and the Berlin government. The question of Hermesianism and the problem of interdenominational marriages offered starting points for disputes . While on the Catholic side there was a change in theological and socio-theoretical understanding, on the Prussian side the state church tradition played a central role. The predominantly Protestant state until 1806 with a king who was also the head of the regional church , faced the attitude of the Catholic Church with incomprehension.

Hermesianism

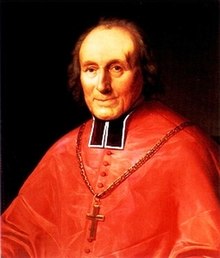

Georg Hermes was appointed Professor of Dogmatics at Bonn University by Archbishop Ferdinand August von Spiegel in 1820 . The philosophical doctrine represented by him represented a critical , psychological and anthropocentric system for the rational justification of the Catholic faith. This doctrine was thus in a certain tradition of the Catholic Enlightenment , for which the co-founder of the Bonn and Münster University Franz Wilhelm von Spiegel ( a brother of Bishop Ferdinand August) and Franz von Fürstenberg were standing. Already during the pre- March period, this attitude came into opposition to anti-enlightenment tendencies in Catholicism, which finally culminated in ultramontanism and the First Vatican Council . Archbishop Spiegel's successor, Clemens August Droste zu Vischering , was already a representative of these new views.

He was thus in line with Gregory XVI. who banned the teaching of Hermes in 1835 with the Breve Dum acerbissimas and placed his works on the index of forbidden books . Clemens August, elected in 1836, considered it his first task to take action against Hermesianism. In exceeding his authority, he forbade theology students from attending appropriate lectures at Bonn University and almost paralyzed teaching in the theological faculty there. Obviously, it was his aim to train the prospective priests at a seminary under his control, modeled on the University of Leuven . By recklessly ruling into the seminar leadership, he became hostile to the Regens and the professors, who then appealed to the Prussian government. In May 1837 he had 18 anti-Hermesian theses printed, to which he wanted to oblige the entire clergy of his diocese . A violent protest on the part of the government did not lead to an open breach , only through the mediation of the Roman Curia . Nevertheless, from the perspective of the Prussian government, these events meant a blatant encroachment on state rights and an overstepping of the church's competences in university policy.

The mixed marriage question

According to the General Land Law of 1794 in Prussia, the decision about the denominational upbringing of children from marriages between partners of different denominations, the so-called mixed marriages, rests with the parents. In the absence of a contractual agreement, sons should be brought up in the denomination of the father and girls in that of the mother. According to canon law, on the other hand, both parties in marriages of different denominations had to promise Catholic baptism and the Catholic education of all children before the wedding . In 1803, a declaration by Friedrich Wilhelm III. that all children from marriages of different denominations should be brought up in the confession of the father. The cabinet order of August 17, 1825 transferred this provision to the western areas that came to Prussia in 1815, where marriages between Protestant military officers or civil servants and Catholic Rhinelander women increased. The Catholic priests were forbidden to demand the promise of Catholic child-rearing as a prerequisite for the solemn consecration. Otherwise, these marriages were considered invalid under civil law . The population , who were already reserved about the Prussians , saw this determination as a conscious attempt at Protestantization. The episcopate and the curia did not dare to resist and exercised tacit tolerance. However, there were also opposed priests who invoked their conscience and the freedom of the Church guaranteed in the federal act .

A papal breve from 1830 provided for the solemn consecration to be refused or for passive assistance to be practiced if the bride refrained from the promise of Catholic child-rearing. Secret negotiations between Christian Karl Josias von Bunsen , the Prussian ambassador in Rome, and Archbishop Spiegel led to the secret Berlin Convention of June 19, 1834, which practically tolerated the Prussian regulations. In return, the government promised to abolish civil marriage in the foreseeable future , although this was never seriously discussed. The exact content of this agreement did not become known to the Curia until 1836. Spiegel's successor, Archbishop Clemens August Droste zu Vischering, declared after initial reluctance in 1837 that, in cases of doubt, he wanted to adhere to the papal breve and not to the agreements with Archbishop Spiegel.

Arrest and imprisonment of the Archbishop of Cologne

Through the Minister of Education, Karl vom Stein zum Altenstein , the Prussian government ultimately demanded that Droste either give in or resign . The pastor harshly invoked his freedom of conscience and the free exercise of the office of bishop. A council of ministers chaired by the Prussian king decided on November 14, 1837, against the concerns of the two ministers Carl Albert Christoph Heinrich von Kamptz and Mühler, to remove the bishop from office. After Archbishop Droste reaffirmed his rigid stance towards President Ernst von Bodelschwingh , he and his secretary Eduard Michelis were arrested on November 20, 1837 and taken to Minden fortress . He was held there until April 1839. In an official audience, the government justified the arrest with revolutionary efforts and breach of word by the archbishop. A detailed indictment was presented to the cathedral chapter .

Rome condemned the actions of the Prussian government with unusually harsh language. The cathedral chapter did not stand behind Droste, but raised serious accusations against the pastor in a report to the curia for his unconciliatory approach in the Hermes and mixed marriages matter. The reason for this attitude was that there were still numerous members in the chapter who had been socialized in the spirit of the Catholic Enlightenment.

With this stance, however, the chapter only represented a minority opinion. The conflict sparked an unusually broad response from the German Catholic public. In the Münsterland there were then tumultuous rallies for the "Martyr of Minden", while the Rhenish population initially remained calm. The pamphlet “Athanasius” published by Joseph Görres in January 1838, which sided with the arrested bishop and promoted an anti-Prussian mood, attracted a lot of attention . In more than 300 publications a violent and sometimes polemical discussion was sparked, which in Prussia did not remain without negative influence on the interdenominational relationship. A delegation of Rhenish and Westphalian nobles interceded in vain for the arrested bishop in an audience with the king.

In the elections for the 6th Provincial Parliament of the Rhine Province , there was a protest election as a result of the turmoil in Cologne . At the electoral assembly of the first electoral district of the second estate (the knighthood) in Düsseldorf, two parliamentary groups were formed. The ultramontanes managed to fully establish themselves. All eight mandates and 12 deputy posts to be awarded in this election went to the Catholic party. A week later the electors' meeting of the second state in the second electoral district was held in Koblenz. Here the Protestants pushed through all the candidates. In the third stand, the victory of the ultramontanes in Aachen and Koblenz in particular caused a sensation. For the first time, denominational affiliation had shaped a provincial state election.

Friedrich Wilhelm IV, who came to the throne in 1840, quickly gave in to the question of mixed marriages in line with his program of an alliance between throne and altar and renounced central state rights in this area, but did not allow the bishop to return to his office. Droste zu Vischering was released from prison as early as 1839 and has lived at his family's headquarters in the Münsterland ever since, but remained in "exile" until his death in 1845.

Historical meaning

The Cologne turmoil is seen in historical research as a factor that contributed to the emergence of political Catholicism through the stages of the revolution of 1848/49 and the Kulturkampf in the 1870s . The fact that this was able to put down particularly deep roots in the Rhineland and Westphalia was not insignificantly related to the confusion in Cologne. The liberal Catholic contemporary journalist Johann Friedrich Joseph Sommer put it at the time: “The events of the time, such as those of the last Decennium [meaning the confusion in Cologne], woke the good-natured Westphalian and contributed in no small part to an end to a certain religious slackening [...] At the same time, the people's movement in connection with the turmoil appeared to him to be a harbinger of the revolution of 1848: The “state had to give way, for the first time the violence trembled before the voice of the people”.

literature

Essays

- Anselm Faust u. a. (Red.): North Rhine-Westphalia. State history in the lexicon . Patmos, Düsseldorf 1993, ISBN 3-491-34230-9 . In it: Jörg Füchtener: Kölner Wirren , pp. 220–222; Manfred Wolf: Catholic Church , pp. 206–210; Alfred Albrecht: Churches, Society and State , pp. 213–217.

- Jochen-Christoph Kaiser : Denomination and Province. Problem areas of the Prussian church policy in Westphalia . In: Karl Teppe, Michael Epkenhans (eds.): Westphalia and Prussia. Integration and regionalism . Schöningh, Paderborn 1991, ISBN 3-506-79575-9 (research on regional history; 3).

- Hans-Joachim Behr: Rhineland, Westphalia and Prussia in their mutual relationship 1815-1945 . In: Westfälische Zeitschrift , Vol. 133 (1983), ISSN 0083-9043 .

Monographs

- Eduard Hegel : The Archdiocese of Cologne between the restoration of the 19th century and the restoration of the 20th century. 1815-1962 . Bachem, Cologne 1987, ISBN 3-7616-0873-X (History of the Archdiocese of Cologne; 5).

- Karl-Egon Lönne : Political Catholicism in the 19th and 20th centuries . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / M. 1986, ISBN 3-518-11264-3 (New Historical Library).

- Heinz Hürten: A Brief History of German Catholicism 1800–1960 . Matthias Grünewald Verlag, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-7867-1262-X .

- Wolfgang Hardtwig : Pre-March . The monarchical state and the bourgeoisie . 4th edition Dtv, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-423-04502-7 .

- Friedrich Keinemann: The Cologne event. Its echo in the Rhine Province and in Westphalia . Aschendorff, Münster 1974 (including habilitation thesis, University of Dortmund 1974).

- Representation . 1974, ISBN 3-402-05222-9 .

- Sources . 1974, ISBN 3-402-05223-7 .

- Friedrich Keinemann: The Cologne event and the Cologne turmoil (1837–1841). Münster, 2015 PDF version

- Rudolf Lill : The settlement of the Cologne confusion 1840-1842. Predominantly based on files in the Vatican Secret Archives . Schwann, Düsseldorf 1962 (also dissertation, University of Cologne 1960).

- Karl Bachem : Prehistory, History and Politics of the German Center Party. At the same time a contribution to the history of the Catholic movement, as well as to the general history of the newer and newest Germany 1815-1914 . Scientia, Aalen 1967/68 (9 vols., Reprint of the Cologne edition 1927).

- Heinrich Schrörs: The Cologne Troubles (1837). Studies on their history . Dümmler, Berlin 1927.

- Ernst von Lasaulx : Critical remarks on the Cologne matter. An open letter to nobody, the public and the public who are capable of judgment . Stahel Verlag, Cologne 1838.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Joachim Stephan: Der Rheinische Provinziallandtag 1826-1840, 1992, ISBN 3-7927-1297-0 , pp. 86-89

-

↑ Hans-Joachim Behr: Rhineland, Westphalia and Prussia in their current relationship , p. 51f.

Jochen-Christoph Kaiser: Confession and Province , pp. 271–277.

Wolfgang Hardtwig: Vormärz , pp. 168–170. - ^ Johann Friedrich Joseph Sommer : Juristic Zeitlaufte . In: New archive for Prussian law and procedures as well as for German private law , vol. 14 (1850), pp. 149–169, 679 ff. ISSN 0935-7068