Federal Council (German Reich)

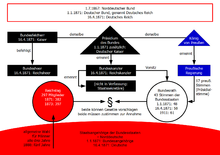

The Bundesrat was a state organ in the North German Confederation (1867-1870) and in the German Empire (1871-1918). As the representative of the member states , it consisted of representatives from the individual states that made up Germany. Federal and Reich laws required the approval of the Bundesrat and Reichstag so that they could come into force. In addition, the Federal Council had a say in other acts of the Reichstag or the Emperor . He was also responsible for certain constitutional tasks.

Constitutional lawyers see the Bundesrat as the highest body of the Reich according to the constitution, although its real political importance was much less. The chairman of the Federal Council was the Federal Chancellor or Reich Chancellor , who as such was only supposed to lead the meetings and implement the resolutions. He had neither a seat nor a vote nor a right of initiative, so he could not propose any laws, although as Chancellor he was the head of the government.

In practice, however, the Chancellor and the Prussian Prime Minister were almost always the same person. The Chancellor was therefore able to appear as a member of the Federal Council through Prussia and introduce legislative initiatives. The Prussian plenipotentiaries had 17 of 58 (from 1911 61) votes. Although this was the highest number of votes, it did not correspond to the actual preponderance of Prussia, which occupied two thirds of the Reich territory. Prussia and the Chancellor needed the support of the other states in the Bundesrat in order to use the power of the Bundesrat for themselves.

designation

A Federal Council was already mentioned in the draft constitution for the German Confederation in 1814/1815. The expression also appears in the Frankfurt Reform Act of 1863. That Bundesrat would have resembled the narrower council of the Bundestag and also the later actual Bundesrat: it would have been a permanent envoy congress with representatives of the individual states.

In the constitutional texts, the Federal Council appears as a Federal Council , the "h" lost the word Rath only through the spelling reform of 1901 . When the North German Confederation was expanded to form the German Empire in 1871, the Kaiser would have liked to rename the Bundesrat the Reichsrat. His chancellor Otto von Bismarck convinced him that the federal character of the body should continue to be emphasized. The Bundesrat therefore only became a Reichsrat in the Weimar Republic .

Competencies

The Federal Council combined legislative and executive powers in accordance with the constitution and imperial laws. With that he was already a constitutional hybrid . He was also entrusted with limited constitutional powers. Legislative and executive functions were:

- Participation on an equal footing with the Reichstag

- in the Reich legislation (Art. 5)

- and with the budget and other financial authority (Art. 69, 73),

- Participation in the conclusion of international treaties and declarations of war (Art. 69),

- With the emperor decision on the dissolution of the Reichstag (Art. 24),

- Issuing statutory ordinances and general administrative provisions (Art. 7),

- Participation in the appointment of Reich officials,

- Determination of deficiencies in the context of Reich supervision (Art. 7),

- Decision to initiate the execution of the Reich (Art. 19).

Since the extension of autonomy in 1877, the regional committee in Alsace-Lorraine has decided on the state laws. However, they were formally issued by the emperor, and the Federal Council had to agree.

No constitutional court was provided for the federal government or the empire , in contrast to the imperial constitution of 1849 , which entrusted such tasks to a supreme imperial court. Bismarck's solution was similar to that in the German Confederation, insofar as the constitution he drafted assigned certain tasks to the Bundesrat:

- Decision on non-private law disputes between member states (Art. 76),

- Settlement of constitutional disputes within the member states (Art. 76),

- Obtaining judicial assistance in the event of a refusal to judge in a member state (Art. 77).

For disputes between and within member states, it seemed legitimate to entrust the federal organ, the Federal Council, with the mediation. In substance, its function was judicial.

functionality

Agents and voting

Each member state could submit proposals to the Federal Council and had at least one vote. If he had more votes, they had to be cast uniformly, since the member state voted and not a single authorized representative could vote at his own discretion. A simple majority of the cast (not: all existing) votes counted. In the event of a tie, the Prussian votes decided.

An authorized representative could, but did not have to be, a state minister. Bismarck wanted state ministers to upgrade the Bundesrat, but instead many member states appointed civil servants or the envoys that their state had in Berlin (member states were still allowed to have their own diplomatic missions abroad ). Prussia increasingly appointed not only its own ministers of state, but also state secretaries of the Reich offices (a kind of Reich minister) as plenipotentiaries in the Bundesrat.

There was one important incompatibility: an authorized representative was not allowed to be a member of the Reichstag at the same time (Art. 9, Paragraph 2). This was seen as an obstacle to the parliamentarization of the executive, even though the chancellor or a state secretary did not have to be a member of the Federal Council. When politicians from the Reichstag became state secretaries in 1917/18, they retained their mandate in the Reichstag and were not appointed as agents of Prussia or any other member state. But that meant they were further from power than their colleagues with members of the Federal Council. In the October reforms of 1918 , the article was not deleted, but the state secretaries were given the right to speak in the Reichstag, even if they were not part of the Bundesrat.

Prussia had a right of veto on certain issues , namely in the field of the military and the navy (Article 5) as well as certain use taxes and customs. The 17 Prussian votes were also sufficient for a veto on constitutional amendments (14 votes).

Distribution of votes

The exact number of votes for the individual member states was specified in the federal constitutions (Art. 6). In 1867 there were 43 votes in total. The numbers went back to the German Bund, whereby in the constitution of 1867 it was noted that Prussia together with the "former votes of Hanover, Electorate Hesse, Holstein, Nassau and Frankfurt" (in the old Bundestag) got 17 votes. Prussia annexed these states in 1866 . In the plenum of the old Bundestag (a total of 70 votes), Prussia and Hanover originally had four votes each, Kurhessen and Holstein three each, Nassau two and Frankfurt one vote, a total of 17 votes.

Hessen-Darmstadt initially only had 1 vote, namely for the part of its national territory that belonged to the North German Confederation. With the constitution of January 1, 1871 and the accession of the rest of Hessen-Darmstadt, this was increased to 3 votes. The same constitution also mentioned Baden's accession with 3 votes. The total number of Federal Council votes increased from 43 to 48 votes. On April 16, Württemberg and Bavaria followed with the renewed constitution. The total number rose to 58 votes. From 1911 onwards, the Reichsland Alsace-Lorraine was granted three Federal Council votes, although it was still not a federal state. That brought the total to 61.

The number of Prussian votes remained unchanged. In 1867, Prussia still had just under forty percent of the Federal Council's votes; with the accession in 1871 this decreased to just under thirty percent and in 1911 to just under 28 percent. For comparison: The Weimar Constitution of 1919 limited the proportion of the Prussian Reichsrat votes to a maximum of forty percent (so-called clausula antiborussica ). About two thirds of all Germans lived in Prussia both during the German Empire and the Weimar Republic.

| Federal State (German Empire) |

Number of votes |

|---|---|

| Prussia | 17th |

| Bavaria | 6th |

| Saxony | 4th |

| Württemberg | 4th |

| to bathe | 3 |

| Hesse | 3 |

| Alsace-Lorraine | 3 |

| Mecklenburg-Schwerin | 2 |

| Braunschweig | 2 |

| 17 small states with one vote each | 17th |

| total | 61 |

Committees

The authorized representatives met partly in plenary sessions and partly in committees. Some of the committees were laid down not only in the rules of procedure but also in the constitution. When Bavaria joined the federal government in 1870, it negotiated the chairmanship of the Committee on Foreign Affairs. This did not result in any particular political weight. Prussia chaired the other committees.

The standing Federal Council committees were:

- Committee on the Land Army and Fortresses,

- Maritime Committee (Navy),

- Customs and Taxation Committee (Finance),

- Committee on Trade and Transport,

- Committee on Railways, Post and Telegraphs,

- Judiciary Committee,

- Accounting Committee,

- Committee on Foreign Affairs,

- Alsace-Lorraine Committee,

- Constitutional Committee,

- Rail Freight Tariff Committee.

Origin and position in the political system

Idea of the princely aristocracy

According to the Imperial Constitution , the Federal Council was the supreme organ of the entire state and the bearer of the sovereignty of the Reich. According to the doctrine of constitutional law, the empire is a princely aristocracy. With this veiling depiction one avoided the crucial question of whether the emperor or the Reichstag took the sovereign position, i.e. whether the empire was a constitutional monarchy or a parliamentary democracy.

The confusion was caused by the fact that in the constitutional monarchy the prince was nominally the ruler but did not rule. All actions of a prince required the countersignature of a minister. So it was not the princes who founded the Bund or the Reich (as it seemed according to the constitutional preamble), but the governments, together with the Reichstag. It was not the princes who were members of the Bundesrat, but rather they set up governments, which in turn sent authorized representatives to the Bundesrat with instructions.

Original concept

In addition, the original draft constitution, as presented to the constituent Reichstag in 1867 , provided for another role for the Bundesrat. The Bundesrat should de facto represent the government, the Chancellor (and chairman of the Bundesrat) would have been just a “mere executive assistant” ( Michael Kotulla ). This would have made the Bundesrat even more similar in many ways to the old Bundestag of the German Confederation. The Chancellor would have complied with the “presidential envoy” in the Bundestag, the envoy from Austria, who presided over the Bundestag and whose “presidential vote” was decisive in the event of a tie. Otherwise, the presidential envoy in the Bundestag had no special powers. Bismarck imagined that, as Prussian Prime Minister, he instructed the presidential votes of Prussia in the Bundesrat and would also have decisive influence on the Chancellor, even if the Chancellor himself was appointed by the Federal Presidium (the Prussian King). As Chancellor, Bismarck had already thought of Karl Friedrich von Savigny , the last Prussian envoy to the Bundestag.

The constituent Reichstag, on the other hand, was of the opinion that such a system would have made the federal executive more or less invulnerable to the Reichstag. Instead, the Reichstag demanded a responsible government, as in Prussia, for example. At that time, responsibility was not considered to mean that a government would have to resign at the request of parliament. But by countersigning, the government took responsibility for the monarch's actions. In this way, the government in the constitutional monarchy was no mere stooge of a monarch who himself was still considered inviolable (and could not be charged).

Chancellor and Federal Councilor

The compromise between the Reichstag and Bismarck ( Lex Bennigsen ) found in 1867 ensured that the Chancellor was still a responsible minister, even if the word "minister" does not appear in the constitutional text. Only then did Bismarck decide to become Chancellor himself. He remained Prussian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister. At first this made sense if only because the federal executive did not yet have its own government apparatus. The constitution itself, however, did not stipulate that the Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister had to be the same person.

Bismarck and his successors only acquired their strong position in the political system through this combination. The chancellor's powers were rather meager because of the history of this office. Unlike in many other states had the chancellor in parliament (the Diet) no right to speak, he or emperor could the Diet no bills to present, had no right to veto laws and could not resolve the Reichstag. However, thanks to his position in Prussia, the Chancellor became a member of the Federal Council, thereby receiving the right to speak in the Reichstag, and he had the 17 Prussian Federal Council votes. They became the basis for majority decisions by the Federal Council. Although only one member state was allowed to submit proposals to the Federal Council, in practice it was often the Chancellor.

The constitutional power of the Federal Council thus benefited the Chancellor. That is why the Chancellor always treated his Federal Council colleagues very courteously. This in turn helped the Federal Council to appear unanimously to the outside world. For example, they never used their right to speak in the Reichstag to express a dissenting opinion.

In contrast to the permanent strong competence of the Federal Council stood the disinterest of the general public. It is true that the Federal Council had a high reputation among experts. But he was neither particularly criticized nor did he attract affection. That was due to the fact that the Federal Council did not meet in public. Precisely because the Bundesrat was an important instrument for him and emphasized federalism in the Reich, Bismarck wanted the Bundesrat to be upgraded. He thought of making the meetings public, but this would not have changed the fact that the people were more interested in the unitarian (unified state) organs such as the Kaiser and the Reichstag.

First World War

Shortly after the outbreak of the war, the Reichstag adopted on 4 August 1914 unanimously adopted a series of laws: This included the law on the authorization of the Federal Council on economic policies and on the extension of time limits in the bill and check law in the event of acts of war , short of war Enabling Act . With this Enabling Act , the Reichstag transferred some of its rights of participation in legislation to the Bundesrat.

That was in itself unconstitutional or a constitutional breach , as it was quite controversial in constitutional law. The term economic was flexible, but the Federal Council made moderate use of the War Enabling Act. He had to submit the statutory emergency ordinances to the Reichstag, which in turn only rarely raised objections. Both organs shied away from open conflict.

Towards the end of the war, a meeting took place in the Reich Chancellor's Palace on November 10, 1918 . The new Council of People's Representatives , which exercised the rights of the Emperor and the Chancellor, had also invited the Reichstag President Constantin Fehrenbach . Council chairman Friedrich Ebert said at the meeting that the Reichstag should not be convened again; There is still no decision on its dissolution.

According to the constitution, a resolution by the Federal Council would have been necessary for the dissolution of the Reichstag. In the revolution , however, there was no room for the Federal Council as an executive and legislative body. On the other hand, Ebert did not want to simply dissolve the Federal Council in order not to turn the (meanwhile also revolutionary) state governments into opponents. On November 14th, the council finally issued a regulation according to which the Federal Council should continue to exercise its administrative powers. This implicitly meant that the other competencies had ended.

See also

- Plenipotentiary of the state governments

- Reichsrat

- Federal Council (Germany)

- Bundestag (German Bund)

- Federalism in Germany

Web links

supporting documents

- ↑ Eisenbahndirektion Mainz (ed.): Official Journal of the Royal Prussian and Grand Ducal Hessian Railway Directorate in Mainz of November 30, 1912, No. 60. Announcement No. 718, pp. 447f.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 501.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume IV: Structure and crises of the empire . Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1969, p. 453.

- ^ According to Ernst Rudolf Huber: German Constitutional History since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the Reich. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, pp. 860, 1065.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 501.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 859.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 849.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 502. Literally: "In this way, the Chancellor grew beyond the role of a mere executive assistant to the Federal Council [...]."

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, p. 857.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 851/852.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, pp. 850, 852.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1978, pp. 37, 62 f.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1978, pp. 64, 67.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume V: World War, Revolution and Reich renewal: 1914-1919 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1978, pp. 729/730.