Federal Chancellor (North German Confederation)

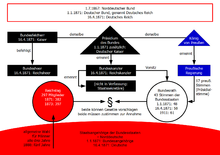

The Chancellor was in 1867, the executive of the North German Confederation . According to the constitution of the North German Confederation , he was appointed by the holder of the Federal Presidium , i.e. by the Prussian King . The Federal Chancellor had ministerial responsibility and countersigned the actions of the Federal Presidium. The office is identical to the Chancellor of the German Empire .

In the original draft of the constitution, the Federal Chancellor was supposed to be a purely executive officer. The business of government was with the Federal Council . This representation of the member states would have done this through committees. But the constituent Reichstag (February to April 1867) rejected such a construction. Through the " Lex Bennigsen " the half-sentence was inserted that the Federal Chancellor assumes responsibility.

Apart from that, the Federal Chancellor had another function according to the constitution: He was chairman of the Federal Council. Otherwise, however, the Chancellor was not a member of the Federal Council and did not have a Federal Council vote. However, he received further rights de facto because he was almost always the Prussian Prime Minister at the same time. During the transition to the German Empire (from January 1, 1871) the office of Federal Chancellor remained the same, but on May 4, 1871 it was renamed " Reich Chancellor ".

Office in practice

The only Federal Chancellor during the time of the North German Confederation was Otto von Bismarck , the Prussian Prime Minister and Foreign Minister. King Wilhelm I appointed him on July 14, 1867. This first act of the king for the federal government was countersigned by two Prussian ministers . However, there was no basis for this in either the Federal Constitution or the Prussian Constitution.

Supreme Federal Authorities

Bismarck did set up a Federal Chancellery . However, he refused to accept the Reichstag's request to allow proper federal ministries. In addition to the Federal Chancellery, there was only one other supreme federal authority during the North German Confederation: at the beginning of 1870, the Prussian Foreign Ministry was transferred to the Federal Government and was given the name "Foreign Office of the North German Confederation".

The heads of the Chancellery and the Foreign Office received the title of " State Secretary ". They were not Bismarck's colleagues, but officials who were subordinate to the Chancellor and to whom he could give instructions.

Office connection between Chancellor and Prime Minister

When the federal government was founded, Bismarck introduced a practice that was to last almost until the end of the Empire: he held the offices of Federal Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister at the same time. That was not required in the constitution. The offices remained two different offices in themselves.

For Bismarck and his successors, this office connection had a great advantage: As Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Prussia, he had the greatest influence on the Prussian government. The Foreign Minister determined who represented the country in the Bundesrat and how the delegates had to vote. Bismarck also made himself a member of the Federal Council. In the Bundesrat, Prussia alone did not have a majority, but it did have the most votes. So Bismarck had the greatest influence on the Federal Council.

This gave him the power of the Bundesrat, especially when it came to legislation : Federal laws could only be passed if, in addition to the Reichstag, the Bundesrat also approved. In addition, Bismarck only automatically had the right to speak in the Reichstag as a member of the Federal Council, not as Federal Chancellor.

According to the Federal Constitution, only one member state or its representative could make proposals to the Bundesrat (Art. 7). However, it has become a common practice for Chancellor Bismarck to introduce bills to the Bundesrat as drafts of the federal executive. In this way, the federal executive received a de facto right of initiative and a right of veto. With the office connection, Bismarck compensated for the rather weak position that the Federal Chancellor had according to the constitution. For comparison: in Prussia the king or the government already had these rights expressly through the Prussian constitution.

Transition to the German Empire

Because of the accession of the southern German states ( November treaties ) to the Federation, the Reichstag and Bundesrat adopted a new constitution: This " Constitution of the German Confederation ", which came into force on January 1, 1871, gave the existing state a new name, "German Reich" . The political system and the tasks of the executive did not change.

However, the designation for the executive remained "Federal Chancellor". On May 4, 1871, a new, revised constitution came into force, making it a "Reich Chancellor". Bismarck simply stayed in office: there was no interruption in his activity or reappointment.

In doing so, Kaiser Wilhelm emphasized that the Federation and the Reich and thus the organs were identical, despite the renaming. The Kaiser had been addressing his letters to the Federal Chancellor since January 1st with "From the Emperor's Majesty to the Reich Chancellor ". Otherwise, the constitutional term was still used officially. Only after the revised constitution was officially referred to as the "Reich Chancellor" and the "Reich Chancellery".

See also

supporting documents

- ^ Michael Kotulla : German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, pp. 492/493.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 668.

- ^ Michael Kotulla: German constitutional history. From the Old Reich to Weimar (1495–1934) . Springer, Berlin 2008, p. 544.

- ^ Ernst Rudolf Huber: German constitutional history since 1789. Volume III: Bismarck and the realm. 3rd edition, W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart [u. a.] 1988, p. 755.