Constitution of the North German Confederation

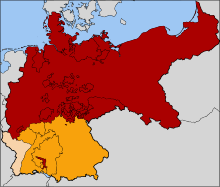

The constitution of the North German Confederation was in force from July 1, 1867 to December 31, 1870. It was the basis of Bismarck's Imperial Constitution and was intended to make accession as acceptable as possible to the southern German states.

Basic features of a new federal constitution of June 10, 1866

After the failure of the revolution in 1848/49 , the Prussian government was convinced that the German people would continue to pursue their "salvation from fragmentation and powerlessness" regardless of the continued existence of the individual states and the nobility still ruling in them. The Prussian government made itself an advocate of the unification movement in order to preserve the Prussian, anti-democratic state and social order.

On June 10, 1866, the Prussian government presented the “ Basic Features of a New Federal Constitution ” to the other German states . The most important principles were formulated in ten articles: An assembly of the plenipotentiaries of the individual states similar to the federal assembly, the later Federal Council, should be responsible for legislation together with a national assembly . The National Assembly, like the Reichstag, should emerge from the Paulskirche constitution from general, equal and direct elections. The federal government should primarily have its legislative competence to create a single currency, economic and customs area. Political freedoms, such as the exemption from unequal voting rights in the individual states and fundamental rights, were not provided. The head of state was not mentioned as to who should be given government responsibility, who forms the government and who exercises control over it. This is where the main features of the Prussian government differed from the Paulskirche constitution.

The federation should have two armies, a Northern Army with the King of Prussia as General and a Southern Army with the King of Bavaria as General. The uniform navy should be under the supreme command of the King of Prussia.

In contrast to political freedoms, the basic features of the individual states' shares of military spending were precisely regulated. Each individual state should in principle pay a contribution based on the headcount of its inhabitants. He should initially bear the expenses for his troops himself and deduct this amount from the matriculation fee. Any surplus that is not required should be administered as Federal War Treasury by a Federal War Council and controlled by the National Assembly.

In the alliance treaty of August 18, 1866, the northern German states agreed to found a nation state against the resistance of the regional parliaments . First of all, the Reichstag was to be elected as a constituent assembly according to general, equal and secret suffrage, the suffrage of the revolution. The governments of the northern German states should then submit a draft constitution for final approval.

Preparatory work by the Prussian government for the constitution

The Duncker design

Maximilian Duncker prepared an elegantly formulated draft on behalf of the Prussian Prime Minister Otto von Bismarck until September 1866. The proposal itself was felt to be too cumbersome and centralistic and in the course of further development was only used as a counter-model and not as a prototype of the constitution.

In Duncker's draft, federal responsibility included foreign policy, the military, federal finance and many responsibilities in individual areas that were supposed to create a unified economic, monetary, legal and traffic area. The federal government should promote legal unity through federal legislation. According to the constitution itself, only the law of obligations and the law of civil procedure should be unified.

If, however, responsibilities were not expressly transferred to the federal government, the individual states should retain their sovereign and property rights. This formulation was no longer found in the constitution, although the principle was retained.

The governments of the individual states should form a council of state known as a federal assembly by sending delegates. Each state had a vote. The State Council had the right of initiative and discussed all draft laws. A veto against draft legislation had to bring only the King of Prussia, who could not be compelled against his will, a bill in the Reichstag. The representative of the King of Prussia chaired the Council of State.

The Reichstag consisted of a people's and states' house. The state house had 110 seats. Prussia received 60 seats to guarantee its hegemonic position, the other individual states shared 50 seats. Half of the members of the House of States were appointed by the governments and the other half by the representative bodies of the individual states. The Volkshaus was elected for three years according to equal and universal male suffrage. Federal laws required the approval of both houses. The Volkshaus was not involved in concluding alliances and treaties with other states. The government could neither vote nor vote out and was only responsible for legislation and the federal budget.

The King of Prussia was the holder of the Federal Presidium and General Supreme Leader of the Confederation with authority over the armed forces and the navy. As the holder of the Federal Presidium, the King of Prussia was head of state and represented the Federation externally. With the consent of the State Council, he was able to conclude alliances and treaties. The King of Prussia was able to issue executive ordinances to laws and, together with the Council of State, supervise the implementation of federal laws by the individual states and the federal administration. The King of Prussia held all government powers of the Confederation and exercised it through ministers appointed by him. Actions by the King of Prussia in government and legislation did not take effect until a minister countersigned him, who thereby assumed political responsibility.

The federal budget was to be determined in the first Reichstag jointly by the people and states; only the later increases and changes in expenditure would have to be decided again. The waiver of a catalog of basic rights was retained in all later drafts and in the constitution. The individual states were able to retain their administrations with responsibilities and personnel in the constitution. The waiver of a Reichsgericht as a constitutional court has also remained. Following the example of the German Confederation, the settlement of constitutional disputes remained with the representation of the individual states.

Approach to the German Federal Act

In the Putbus dictation of October 30, 1866, a memo for Karl Friedrich von Savigny , Bismarck commented on the previous drafts by Maximilian Duncker , Robert Hepke and Lothar Bucher . The drafts are too unitarian and too centralistic, also for the future accession of the southern German states. Three legislative bodies, the People's House, the State House and the Federal Council are too cumbersome. At most he thought it conceivable to have the Reichstag elected in two sections. Half of the MPs were to vote for the 100 most taxed persons in a constituency, the other half for the remaining voters.

There should not be a responsible government based on the model of the Paulskirche constitution or the Erfurt Union constitution. Instead, central offices should be set up at the Federal Council with specialist commissions appointed by the governments of the individual states. The Federal Council should thus become a government body. According to a further note on the file, the Putbus dictation of November 19, 1866, the Federal Council was to take over the tasks of a ministerial bank with 43 seats.

Robert Hepke then worked out two alternative drafts to the Federal Council: A small Federal Council based on the closer council of the German Confederation should have eight votes, two of which for Prussia. A large Federal Council, similar to the plenary assembly of the German Confederation for constitutional questions, should have 43 votes, 17 of them for Prussia. Only the big Federal Council was followed up.

After several revisions and corrections by Bismarck, Lothar Bucher created a draft with 65 articles on December 8, 1866, which he revised on December 9. This draft went to the Prussian cabinet for approval. For the meeting of the Council of Ministers on December 13th, a draft with 69 articles, which Bismarck made many changes and which was revised, was drawn up. Bismarck's changes were reversed at the meeting. On December 15, 1866, the draft of the Prussian cabinet was forwarded to the governments of the northern German states. The constituent Reichstag was elected on February 12, 1867, and it met for its first session on February 24, 1867. The governments adopted Bismarck's last amendments and submitted them to the Reichstag on March 4, 1867.

The Federal Council

The member states sent representatives to a Federal Council, which participated in legislation on an equal footing with the Reichstag. In line with the Federal Assembly of the German Confederation, Prussia was entitled to 17 out of 43 votes, thus securing its hegemonic position. No constitutional amendment could be passed against Prussia , as this required two thirds of the votes . The alternative to this would have been to give the King of Prussia an equal share in the legislation, so that he would have a right of veto. Bismarck feared that the individual states would not agree to such a regulation.

The 17 votes for Prussia were justified:

- with four votes for Prussia as in the plenum of the German Confederation,

- with four votes for the annexed Kingdom of Hanover

- with three votes for the annexed Kurhessen

- with three votes for the annexed Holstein

- with two votes for the annexed Nassau and

- with one vote for the annexed city of Frankfurt.

Only the voting leader of the respective state cast the votes uniformly, not the other representatives. They didn't even have to be present. An inconsistent and therefore ineffective vote was excluded. The vote could only be cast as decided by the state government. The Federal Council participated in legislation on an equal footing with the Reichstag. No law could come into force without the consent of the Federal Council. In more recent constitutions, the House of States' right to participate is somewhat weaker. The Federal Council should form permanent committees to draw up draft bills , the justifications for bills and to prepare other materials.

Since the Federal Council and the Reichstag had a right of veto and a standstill in legislation had to be avoided, they were participants in a cooperation model. Federal Council decisions were prepared in informal coordination meetings. Saxony was consulted in advance on important matters. After 1871 all medium-sized states were included in advance, the largest of which, Bavaria, had six votes.

The Federal Council did not yet have the right to issue general administrative regulations on federal laws and to determine the organization of the authorities. He was only entitled to do this after the constitution of the German Empire in 1871. However, the Federal Council was able to exercise general control over the federal administrations. Each individual state was entitled to make proposals for exercising federal supervision, to represent them and to have them discussed in plenary. The orders and orders to the federal administrations were not made by the Bundesrat, but by the King of Prussia. However, they were prepared by the chairman of the Bundesrat, the Federal Chancellor, submitted to the King of Prussia for drawing and then countersigned by the Federal Chancellor to assume responsibility.

The constitution of the North German Confederation did not expressly stipulate who is the holder of the state's omnipotence. In the states of the German Confederation, the princes and the free cities were the sovereigns. The entire state power remained united in the head of state, the prince. Constitutions could only limit the exercise of individual rights. The Paulskirche constitution assigned sovereignty to the Reichstag; where this was not responsible, there was a secondary responsibility for the Emperor Bismarck and his employees tried to avoid a direct formulation. Bismarck wanted to create a federal state that resembles a confederation. The state, not personal sovereign, should be formed by the individual states united in the Bundesrat in their entirety.

The Chancellor

According to the Prussian draft constitution, the Federal Chancellor should only chair the Federal Council and manage its affairs. Since the Federal Council was the bearer of sovereignty, in particular it drafted the bills and brought them to the Reichstag, the position of the Federal Chancellor was already strong. In addition, the Federal Council had to decide on the applications of the individual states to organize the federal administration and to transfer them to the King of Prussia. In their submission to the Reichstag, the northern German governments introduced the Federal Chancellor's obligation to countersign: all orders of the King of Prussia had to be countersigned by the Federal Chancellor in order to be effective.

Beyond the wording of the constitution, the countersigning obligation extended to all governmental acts of the King of Prussia as the holder of the Federal Presidium, as in the Paulskirche constitution, including real acts such as speeches and handwriting. The Reichstag added that the Federal Chancellor also assumes legal and political responsibility with the countersignature. He refused, however, to order the consequences for cases in which the Federal Chancellor violated constitutional or other obligations, for example based on the Prussian model. With the countersignature requirement, the Federal Chancellor - with the exception of the military supreme command - became the highest political federal official and the only federal minister responsible.

The Federal Chancellor's only authority was the Federal Chancellery. It had a central department, a department for the postal system, the general post office and a department for the telegraph system, the general directorate of telegraphs. Administrative tasks for the entire armed forces were carried out by the Prussian War Ministry. The Prussian Minister of War was appointed as the Prussian Federal Councilor, so that he could appear in the Federal Council and in the Reichstag. Foreign affairs were dealt with in the Prussian Foreign Ministry until 1870, matters relating to the Navy in the Prussian Navy Ministry. It was only with the establishment of the Reich in 1871 that numerous upper Reich offices emerged that performed the tasks of Reich Ministries and whose State Secretaries and Presidents were subordinate to the Reich Chancellor.

The Reichstag

The Reichstag was the democratic and unitarian organ of the North German Confederation, which participated in federal legislation on an equal footing with the Bundesrat. The Reichstag was of course not a full parliament, as it was dependent on other state organs and had no comprehensive rights of control over the government. The Reichstag also did not have the right to self-assemble. It was only up to the King of Prussia to convene, open, adjourn and close the Reichstag. The Federal Council was able to dissolve the Reichstag by mutual agreement with the King of Prussia.

The Reichstag was also not entitled to a general reservation of approval for international treaties, but only for objects for which the federal government had the right to legislate. International treaties were not included. In this way, a secret diplomacy that was not known to the Reichstag and thus also to the public could continue. According to the draft of the Prussian government, the King of Prussia should be solely responsible for the conclusion of all international agreements. In their submission to the Reichstag, the allied northern German states enforced at least one requirement for approval by the Bundesrat. The Reichstag itself then enforced an authorization requirement from the Reichstag in the deliberations, but only for items that were subject to federal legislation.

The Reichstag could neither elect nor vote out the government. One government wanted to avoid Bismarck because he feared that it could be held accountable to the Reichstag. He also feared the example of the collegially composed Prussian Council of Ministers, because it did not give the leading minister any clear political responsibility. In their submission to the Reichstag, the governments of the individual states pushed through that the orders and orders of the King of Prussia in federal matters must be countersigned by the Federal Chancellor. It was not until the Reichstag that the chairman of the Federal Council and the Federal Chancellor were responsible for the government of the King of Prussia. As a result, the level of responsibility of the Paulskirche constitution was achieved again. However, the Reichstag was unable to enforce the responsibility of the Federal Chancellor either by deselection or by a ministerial charge before a federal court, as in the Paulskirche constitution.

The Reichstag was to emerge from general, equal, direct and secret elections. The North German Federal Constitution indirectly referred to the Frankfurt Reich Election Act of April 12, 1849, in which these principles were implemented. Bismarck considered the renunciation of the familiar three-class voting rights and the interposition of electors to be easy and useful. For reasons of foreign policy, Bismarck adopted the general suffrage of the Paulskirche constitution "as the strongest of the liberal arts" in the main features of a new federal constitution of June 10, 1866. Bismarck hoped that Austria and Russia would not attract their people's attention to the general suffrage that was withheld from them and would therefore pass over the emergence of a new middle power in Europe with silence.

Bismarck considered the principle of secret voting in elections to be dangerous. In the case of anonymous voting, masses could assert themselves with blunt, undeveloped judgment, who would like to be lied to because of their desires. In the Prussian draft to the governments of the individual states, therefore, no secret electoral law was provided for. The draft of the allied North German governments to the Reichstag then referred to the Frankfurt Reich Election Law, which ordered secret elections with the wording "Ballot without signature".

The Prussian government draft and the submission of the North German governments to the constituent Reichstag of the North German Confederation hardly contained any provisions on the organization and protection of parliamentary activities. Only the Reichstag made the prosecution of members dependent on the prior consent of the Reichstag. Promoted officials were banned from exercising their mandate, which meant that members of the Reichstag were not to be appointed heads of the highest Reich authorities. As a result, a lot of experience was foregone. The ban on diets, with which members of the poor should be kept away from the Reichstag, was not changed.

The debates of the Reichstag made politics - with the exception of foreign and military policy - accessible to the public, because the debates of the Reichstag were public. Members of the Reichstag could neither be prosecuted under civil law nor criminal law for their statements in the Reichstag. Journalists who reported on debates in the Reichstag enjoyed the same privilege.

The legislative process

Two concurring resolutions by the Reichstag and Bundesrat were required for a federal law. Both could block each other. A legislative emergency could arise from such blockades. To end it, the Federal Council was able to dissolve the Reichstag in agreement with the King of Prussia and the countersigning Chancellor. Since the dissolution was not tied to any prerequisites, the government side could justly have a parliament that it approved; however, this abuse did not arise until the later German Empire (1878, 1887, 1893, 1906).

The problem was solved even worse in the Weimar Constitution: there was the right of the Reich President to issue emergency ordinances, which invited people to issue emergency ordinances outside of a legislative emergency. The legislative emergency is therefore closely regulated in the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany : The Bundestag can only be dissolved at the request of the Federal Chancellor. If the Federal Chancellor receives the confidence and if the Bundestag rejects the act designated as urgent, it can come about by a unanimous decision of the Bundesrat and the Federal Government. The majority factions in the Reichstag were flexible in the adoption of laws, because they could not lose the status of government faction because the government was not dependent on them.

The King of Prussia

The King of Prussia was in personal union and through the Realunion of Prussia the head of state of the North German Confederation. As the holder of the Federal Presidium, he had government powers and, without the restrictions of the Federal Presidium, was Commander-in-Chief of the Federal Army and Navy. Because of the royal rights and the restriction of the rights of the Reichstag, the constitution was limitedly monarchical. King of Prussia was the first-born man of the Royal House of Hohenzollern.

As head of state, the King of Prussia was able to conclude alliances and other foreign policy treaties. He only needed the approval of the Bundesrat and Bundestag where the federal government had the right to legislate. A secret diplomacy behind the backs of the people and the Reichstag was therefore possible. Foreign political power also accumulated with the King of Prussia because acts of command and command and military organizational power neither required the approval of the Reichstag nor the countersignature of the Federal Chancellor. The most important authority of the King of Prussia in the North German Confederation was to appoint the Federal Chancellor. The King of Prussia also had the right to oversee the execution of federal laws by the state administration and the federal administration. He did not make the orders and individual regulations in the Prussian name, but for the North German Confederation; they did not take effect until the Federal Chancellor countersigned them.

The King of Prussia had no veto rights in legislation, but he could assert his hegemonic claim in the Federal Council through the seventeen Prussian votes. The Prussian voices were instructed by the Prime Minister of Prussia, who was also Federal Chancellor and Chairman of the Bundesrat. In addition, Prussia had a blocking minority in constitutional amendments, in the military and naval affairs, and in customs duties and consumption taxes and the associated administrative regulations and administrative authorities.

The designation German Emperor, which was provided for in the Paulskirche constitution, was dropped in the Erfurt Union constitution and only used again in the imperial constitution of 1871. Bismarck refrained from using the term Kaiser. He feared that the individual states would reject the designation emperor because they could understand it as a constitutional monarch with his own powers in legislation. A dominant position for Prussia can be achieved more inconspicuously by allocating seventeen votes in the Federal Council.

Military affairs

In the alliance treaty of August 18, 1866 between Prussia and the other northern German states it was agreed that all troops would be under the command of the King of Prussia. In the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866, the King of Prussia was designated as Commander-in-Chief. It was not until the submission of the North German governments to the Reichstag on March 4, 1867 that the term "Bundesfeldherr" was used, which then finally remained in the constitutional text. This prevented individual federal princes from being able to see themselves as federal generals under the umbrella of an "Oberfeldherr". As the “chiefs of the troops in their area”, the federal princes were only contingent lords without any command and control. The oath of the flag still had to be given to them, but obedience to the King of Prussia as a federal general had to be included in it. The peacetime strength was one percent of the population, and the individual states had to pay the federal government an annual contribution of 225 thalers per head of their citizens for each soldier. The army was a federal army and therefore uniform in administration, catering, armament and equipment. The King of Prussia appointed the highest commanding officer of a contingent. The Prussian military legislation was introduced in all individual states, as was the Prussian administrative regulations. The Navy was under Prussian command; the financing came exclusively from the federal government.

Federal finances

The Prussian draft and the draft of the northern German states to the Reichstag only contained cautiously worded regulations. Direct taxes, such as income tax, should remain with the states. The income from customs duties and excise taxes should flow into the federal treasury. The part of the expenses for the armed forces not covered by the contribution contributions, as well as the expenses for the consular system, were to be raised with customs duties and a part of the consumption taxes. If customs and excise duties are insufficient, the individual states should be obliged to make additional contributions. The Reichstag declared the introduction of new federal taxes to be a priority and granted the federal government the option of borrowing. After submitting the individual states to the Reichstag, they also wanted to finance the navy according to the association principle. The Reichstag shifted the burden to the federal government, which was to cover the costs of the navy alone. The Reichstag thereby strengthened its budget rights compared to the bill and achieved a greater degree of separation of the financial economy between the federal government and the individual states. The separation system could be retained until the German Empire. Unitarian mixed financing began in 1879.

Federal jurisdiction

The North German Federal Constitution did not provide for federal courts. The Bundesrat should settle disputes between the individual states. For constitutional disputes within the state, the Federal Constitution provided for expert recommendations or comparisons by the Federal Council, if necessary also with federal laws, if the state constitutions did not have their own regulations.

Since the North German Federal Constitution did not provide for any fundamental rights, there was also no federal court that was supposed to be responsible for violations of fundamental rights. The Reichsgericht was provided for in the Paulskirche constitution and in the Erfurt Union constitution. The North German Federal Constitution left jurisdiction with the individual states, initially to an even greater extent than administrative responsibility.

In 1869 the Federal Higher Commercial Court was set up with its seat in Leipzig. It took the place of the highest court competent under national law in commercial matters. The judges were employed by the Federal Higher Commercial Court and paid from the federal treasury. This restricted the jurisdiction of the individual states. The Federal Higher Commercial Court proved its worth. Numerous laws expanded his competencies until it was absorbed by the Imperial Court in 1879. The introduction of federal jurisdiction was the most important constitutional change during the time of the North German Confederation, although federal jurisdiction for the judicial system was not provided for in the constitutional text.

The individual states

There was no general clause according to which the member states retained their independence unless the federal constitution provides for any restrictions. Maximilian Duncker had adopted it from the Paulskirche constitution and the Erfurt Union constitution in his preliminary draft, but it was no longer included in the draft for the Prussian cabinet. However, the sentence "Within the federal territory the federal government exercises the right to legislate in accordance with the content of this constitution [...]" suggests the reverse conclusion that the member states retained the legislative right insofar as it was not assigned to the federal government. The constitution designated the member states as states, federal states, individual states, as federal members, as members of the federation and indirectly as states.

The individual states retained their status as a state, their constitutions, their rules of succession to the throne, their territories, their populations, their names, their voting rights restricted to certain groups of people and their court ceremonial, which was important for the recruitment of offspring for the administrative staff. The previous responsibilities of the individual states, such as the police, local authorities, budget law, assets of the individual states, religious systems, schools and universities, hospitals, reservoirs and drinking water systems, cultural institutions such as theaters, opera houses, museums, galleries and libraries, also remained unaffected by the federal constitution.

The individual states retained their constitutional capacity and were able to change their internal order. The federal constitution did not prohibit the individual states from changing the monarchical form of government to a republican one and vice versa. The merger and division of individual states was also allowed. On the other hand, the federal state was not prevented from acquiring further competencies by way of constitutional amendments and thus developing it further into a unitary state.

However, the individual states lost their sovereignty as members of a federal state: They could no longer represent themselves vis-à-vis other states; responsibility for this passed to the King of Prussia. Even international agreements on objects that were not subject to federal legislation, including alliance treaties, could only be concluded by the King of Prussia. The King of Prussia also concluded treaties on matters relating to federal legislation, but only with the prior consent of the Federal Council and subsequent approval by the Reichstag. An interference with the internal order of the individual states meant that the federal constitution required them to treat nationals of the other individual states like their own.

The individual states also lost command and control over their armies, which passed to the King of Prussia. As far as laws and ordinances were required, the member states had to adopt the Prussian military legislation; as far as laws were not required, the King of Prussia determined the structure of the contingents, the garrisons, the presence of the troops and their organization, armament, training and the organization of the Landwehr. Not only the past and present, but also the future orders of the King of Prussia for the Prussian army had to be introduced by the member states for their armies. This meant the complete transfer of the Prussian military state to the other states. There were no more navies of the individual states. They became the Federal Navy under the supreme command of the King of Prussia.

The states retained their exclusive legislative power over direct taxes and also retained their tax administrations. There were no federal responsibilities here, neither for legislation, nor for administration, nor for overseeing law enforcement. The federal government was solely responsible for legislation and enforcement supervision of excise taxes and customs duties. Administrative responsibility, the organization of the authorities and the administrative staff remained with the individual states. The federal government exercised enforcement supervision through federal officials at the local authorities, the customs and tax offices and the directive authorities, e.g. B. the regional finance directorates.

The individual states only hired the operations office officials and the lower administrative officials of the post and telegraph offices. The federal government had the right to compete legislation on the postal and telegraph systems. The statutory ordinances for this were issued exclusively by the King of Prussia when the Chancellor countersigned it. The King of Prussia employed the top officials of the interior administration as federal officials, as did the supervisory officials in the districts.

The individual states kept the railways as state railways and their administrative and operating staff. However, the federal government exercised the legislative right and the enforcement supervision. The North German Confederation did not have its own railway staff.

The federal government also had no staff of its own, but only the right to legislate and enforcement supervision in state banking, road construction, waterways and the judiciary, insofar as there was any administrative supervision here because of the independence of the courts.

Contemporary criticism

The publicist Constantin Frantz subjected the constitution to a critical analysis in 1870: The powers of Europe had no interest in maintaining or protecting the North German Confederation. He is uncomfortable for all neighbors. If the North German Confederation were destroyed, Prussia would also fall apart. In fact, Prussia was declared dissolved in early 1947.

The constitution does not want to grant political freedom, but is based on freedom of trade and freedom of movement. Freedom of the press is only understood as part of trade law and freedom of conscience only as part of freedom of movement. Religious restrictions would be prohibited just because freedom of movement and the right of residence should not be impaired. In this way, commercial law becomes the basis of an entire legal development.

Only through the activity of the Federal Chancellor is the North German Confederation capable of acting and viable. The Federal Chancellor is therefore the real holder of federal authority. For the federal government, changing the chancellor could therefore become a question of survival. The prediction was correct. The Chancellors who followed Bismarck were not up to their office. Even the strongest of his successors, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg , was only able to support the measures of the Supreme Army Command politically towards the end of his term of office.

It makes no sense to bind the federal general status to the King of Prussia only, because such an office cannot be hereditary. Since the King of Prussia is not provided with any other organ and no participation by the politically responsible Federal Chancellor is provided, there is no safeguard against abuse of power. The prediction turned out to be correct. In 1914, the emperor authorized the highest army command to exercise his command and command. It was not controlled by the Federal Chancellor or the Kaiser, and not indirectly by the Reichstag through budget law.

The federal monarchy could absorb the previous principalities. The German princes formed their own class and were therefore stronger than the princely heads of the centralized countries. If the princes, including the lesser ones, fell away, the dynastic system of Europe and with it the monarchical principle would fall apart . The monarchy lived only 52 years. However, the decline in authority came from the Emperor and King of Prussia and not from the princes of the individual states.

rating

Since the constitution was superseded by the Bismarckian Reich constitution after only four years, there is no individual constitutional history . Weaknesses in the constitution, such as the unstable equilibrium between the King of Prussia and the Federal Chancellor and between the Federal Chancellor and the Reichstag, remained hidden because Bismarck could exercise the office at his own political discretion. The majority in the Reichstag was of the opinion that the constitution had proven itself brilliantly. The North German Confederation was successful because the Reichstag with a liberal majority, Federal Councilor, Federal Chancellor and the President of the Federal Chancellery, Rudolf von Delbrück , were able to create the long-awaited unified economic area in just four years. The unregulated opposition between the Federal Chancellor, the Bundesrat and the Reichstag did not break up because of the liberal majority and its success story. Only later did the little influence of the Chancellor and the Reichstag on foreign policy become noticeable, and it was not until the 20th century that an incorrectly composed Reich leadership and an uncontrolled Supreme Army Command brought the monarchical federal state a deep fall.

literature

- Contemporary

- Constantin Frantz : The dark side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian point of view. A political science sketch. Stilke & van Muyden, Berlin 1870.

- Paul Laband : The constitutional law of the German Reich. Volume 1, Tübingen, 1876.

- Paul Laband: The changes in the German Reich constitution , lecture from March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895.

- Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme : The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930.

- Otto von Bismarck: Thoughts and Memories , Stuttgart and Berlin 1928.

- General

- Otto Becker / Alexander Scharff (eds.): Bismarck's wrestling around Germany's design , Heidelberg 1958.

- Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth : Constitutional History , 14th edition, Munich 2015.

- Lothar Gall : Bismarck - the white revolutionary , 2nd edition, Berlin 1990.

- Lothar Gall: Bismarckian Prussia, the Empire and Europe. In: Citizenship, Liberal Movement and Nation - Selected Essays , Munich 1996.

- Knut Ipsen : International Law. 5th edition, Berlin 2004.

- Gerhard Lehmbruch : The Unitarian Federal State in Germany: Path Dependence and Change. Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne 2002.

- Lothar Machtan : Make your dirt avenue! How Germany's monarchs fell out of history. Augsburg 2012.

- Herfried Münkler : The great war. Die Welt 1914 to 1918. Hamburg 2015.

- Klaus Erich Pollmann : The North German Confederation - a model for the parliamentary development capacity of the German Empire? In: Otto Plant (Ed.): Domestic Political Problems of the Bismarck Empire , Munich 1983.

- Heinrich Triepel : On the prehistory of the North German Federal Constitution. In: Festschrift for Otto von Gierke, Weimar 1911, reprint Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 589–644 including Appendix 1: preliminary draft by Maximilian Duncker .

- Volker Ullrich : The nervous great power 1871-1918 , rise and fall of the German Empire. Extended new edition, Frankfurt am Main 2013.

- Veit Valentin : History of the Germans , Gütersloh 1993.

- Gottlob Egelhaaf : The rebirth of the German Empire. The Triple Alliance. In: Handbuch der Politik , Volume 2, main part 18: The political goals of the powers in the present , Berlin 1914, pp. 263-268 ( facsimile ).

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Putbuser dictation of October 30, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme: The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Certificate No. 615, p. 167 f.

- ^ Gerhard Lehmbruch : The Unitarian Federal State in Germany: Path dependency and change. Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne 2002, p. 36.

- ↑ Paul Laband : The changes in the German constitution , lecture of March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895, p. 2.

- ↑ Volker Ullrich : The nervous great power 1871-1918 , rise and fall of the German Empire. Extended new edition, Frankfurt am Main 2013, p. 277.

- ^ Veit Valentin: History of the Germans , Gütersloh 1993, p. 446.

- ↑ Lothar Gall : Bismarck - the white revolutionary , 2nd edition, Berlin 1990, p. 385.

- ↑ Art. 8 of the alliance treaty of August 18, 1866.

- ^ Heinrich Triepel : On the prehistory of the North German Federal Constitution , in: Festschrift for Otto von Gierke, Weimar 1911, reprint Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 589–644 including Annex 1: preliminary draft by Maximilian Duncker, p. 617.

- ^ Heinrich Triepel: On the prehistory of the North German Federal Constitution , in: Festschrift for Otto von Gierke, Weimar 1911, reprint Frankfurt am Main 1987, p. 629.

- ^ Heinrich Triepel: On the prehistory of the North German Federal Constitution , in: Festschrift for Otto von Gierke, Weimar 1911, reprint Frankfurt am Main 1987, p. 631, § 5.

- ↑ Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme: The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Certificate No. 615, p. 167 f.

- ↑ Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme: The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Certificate No. 616, pp. 168–170.

- ↑ Article 4 of the German Federal Act of June 8, 1815.

- ↑ Article 6 of the German Federal Act of June 8, 1815

- ↑ Prussian draft of the constitution of the North German Confederation with introduction in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. 17 NBO

- ↑ Article 6 of the German Federal Act of June 8, 1815; Nos. 2, 5, 8, 10, 14, 36.

- ↑ AA for Art. 51 Para. 3 Sentence 2 GG: BVerfG, judgment of December 18, 2002, 2 BvF 1/0.

- ↑ Art. 7 NBO

- ↑ Art. 77 GG

- ↑ Art. 8 NBO

- ↑ a b c Putbuser dictation of October 30, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Certificate No. 615, p. 167 f.

- ^ Gerhard Lehmbruch : The Unitarian Federal State in Germany: Path dependency and change. Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne 2002, p. 44.

- ↑ Art. 7 para. 2 NBO

- ↑ a b c Art. 17 sentence 2 NBA

- ^ Art. 1 of the German Federal Act of June 8, 1815.

- ↑ Art. 57 of the final act of the Vienna Ministerial Conference of May 15, 1820.

- ↑ Article 84 of the Constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849.

- ↑ Knut Ipsen in: ders., Völkerrecht , 5th edition, Berlin 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ a b Putbuser dictation of November 19, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Certificate No. 616, pp. 168–170.

- ↑ Art. 13 of the Prussian draft of the constitution of the North German Confederation with introduction in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. 16 NBO

- ↑ Art. 7 para. 2 sentence 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 18 sentence 2 of the draft constitution of the North German Confederation, submitted to the North German Reichstag on March 4, 1867.

- ↑ Article 74 of the Constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849.

- ↑ Art. 61 of the constitutional document for the Prussian state of January 31, 1850.

- ↑ Stenographic reports on the negotiations of the Reichstag of the North German Confederation in 1867, first volume, p. 402.

- ↑ Paul Laband: The changes in the German constitution , lecture of March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895, p. 14.

- ^ Paul Laband: The changes in the German constitution , lecture of March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895, p. 15.

- ↑ Art. 9 NBO

- ↑ a b Art. 5 NBO

- ↑ Art. 4 NBO

- ↑ Art. 12 NBO

- ↑ Art. 24 NBO

- ↑ a b c Art. 11 para. 2 NBO

- ↑ Art. 22 NBO

- ↑ Art. 12 of the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866.

- ↑ Art. 11 sentence 2 of the draft constitution of the North German Confederation, submitted to the Reichstag on March 4, 1867.

- ↑ Otto von Bismarck: Thoughts and Memories , Stuttgart / Berlin 1928, p. 25.

- ↑ Art. 18 sentence 2 of the draft constitution of the North German Confederation, submitted to the Reichstag on March 4, 1867

- ↑ Art. 17 last half-sentence NBO

- ↑ Art. 126i of the Constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849.

- ↑ Art. 5 of the alliance treaty of August 18, 1866

- ↑ Art. 20 NBO

- ↑ a b c Otto von Bismarck: thoughts and memories , Stuttgart / Berlin 1928, p. 381.

- ↑ Putbuser dictation of October 30, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, The collected works , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Certificate No. 615, p. 167 f.

- ↑ Otto von Bismarck: Thoughts and Memories , Stuttgart / Berlin 1928, p. 382

- ↑ Art. 22 of the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, Die collected Werke , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. V, § 13 Paragraph 2

- ↑ Art. 31 NBO

- ↑ Art. 21 NBO

- ↑ Art. 32 NBO

- ↑ Art. 22 para. 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 30 NBO

- ↑ Art. 22 para. 2 NBO

- ↑ Art. 24 sentence 2 NBO

- ↑ Art. 48 WRV

- ↑ Art. 68 GG

- ↑ Article 81, Paragraph 2, Sentence 1 of the Basic Law

- ↑ Art. 11 NBO

- ↑ Art. 16, 17 NBV

- ↑ a b c Art. 63 NBO

- ↑ Art. 53 sentence 1 NBO

- ↑ Werner Frotscher / Bodo Pieroth : Verfassungsgeschichte , 14th edition, Munich 2015, p. 219.

- ↑ Art. 53 of the constitutional document for the Prussian state of January 31, 1850

- ↑ Art. 11 para. 2, Art. 4

- ↑ Art. 17 sentence 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 15 NBO

- ↑ Art. 78 NBO

- ↑ Art. 5 Para. 2 NBO

- ↑ Art. 37, 35 NBV

- ↑ Article 27 of the Constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849.

- ↑ Article 66 of the Constitution of the German Empire of May 26, 1849

- ^ Art. 4 of the alliance treaty of August 18, 1866

- ↑ Art. 56 of the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, Die collected Werke , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. 59 of the draft constitution of the North German Confederation, submitted to the Reichstag on March 4, 1867

- ↑ Art. 66 NBO

- ↑ a b Art. 64 sentence 2 NBO

- ↑ Art. 60 NBO

- ↑ Art. 62 NBO

- ↑ a b c Art. 63 para. 5 NBO

- ↑ Art. 61 NBO

- ↑ Art. 53 NBO

- ↑ Art. 36, Paragraph 1 of the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, Die collected Werke , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. 38 of the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, Die collected Werke , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. 53 of the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, Die collected Werke , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. 70 NBO

- ↑ Art. 73 NBO

- ↑ Art. 47 of the Prussian draft of the North German Federal Constitution of December 14, 1866, printed in: Otto von Bismarck / Friedrich Thimme, Die collected Werke , Volume 6a, Berlin 1930, Document 629, pp. 187–196.

- ↑ Art. 53 para. 3 NBO

- ↑ Art. 69 NBO

- ↑ Paul Laband: The changes in the German constitution , lecture of March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895, p. 26.

- ↑ Art. 76 NBO

- ↑ Art. 126 letter i of the Constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849

- ↑ Art. 124 letter g of the Constitution of the German Empire of May 26, 1849

- ^ Paul Laband: The changes in the German constitution , lecture of March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895, p. 32.

- ↑ § 12 ROHG-G

- ↑ § 5 ROHG-G

- ^ Paul Laband: The changes in the German constitution , lecture of March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895, p. 33 f.

- ↑ Paul Laband: The changes in the German constitution , lecture of March 16, 1895, Dresden 1895, p. 34.

- ↑ a b Art. 4 No. 13 NBO

- ↑ Article 5 of the Constitution of the German Empire of March 28, 1849.

- ↑ Article 5 of the Constitution of the German Empire of May 26, 1849.

- ^ Heinrich Triepel: On the prehistory of the North German Federal Constitution , in: Festschrift for Otto von Gierke, Weimar 1911, reprint Frankfurt am Main 1987, pp. 589–644 including Appendix 1: preliminary draft by Maximilian Duncker, p. 631.

- ↑ a b Art. 2 sentence 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 1 NBO

- ↑ a b Art. 3 NBO

- ↑ Art. 54 Para. 4 NBO

- ↑ Art. 7 para. 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 6 NBO

- ↑ Art. 50 Paragraphs 4 and 5, Art. 56 Paragraph 2 NBO

- ^ Paul Laband: The constitutional law of the German Empire. Volume 1, Tübingen 1876, p. 109 ff.

- ↑ Art. 11 para. 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 61 para. 1, 63 para. 1, 63 para. 2 NBO

- ↑ Art. 61 para. 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 63 para. 4 NBO

- ↑ Art. 53 para. 1 NBO

- ↑ Art. 35 NBO

- ↑ Art. 36 para. 1 NBO

- ↑ a b Art. 36 para. 2 NBO

- ↑ Art. 50 para. 5 NBO

- ↑ Art. 43-45 NBV

- ↑ Art. 4 No. 3 NBO

- ↑ a b Art. 4 No. 8 NBA

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 8.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 36.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 39.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 40.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 41.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 23.

- ↑ Herfried Münkler : The great war. Die Welt 1914 to 1918. Hamburg 2015, p. 293.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 27.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 26.

- ↑ Herfried Münkler : The great war. Die Welt 1914 to 1918. Hamburg 2015, p. 288.

- ↑ Constantin Frantz: The shadow side of the North German Confederation viewed from the Prussian standpoint. Berlin 1870, p. 73.

- ↑ Lothar Machtan : Make your dirt avenues! How Germany's monarchs fell out of history. Augsburg 2012, p. 116 f.

- ↑ a b Lothar Gall: Bismarcks Prussia, the Reich and Europe in: Bürgerertum, Liberale Bewegungs und Nation - Selected essays, Munich 1996, p. 225, fn. 16.

- ↑ Klaus Erich Pollmann : The North German Confederation - a model for the parliamentary development capacity of the German Empire? , in: Otto Plant (Ed.): Domestic Political Problems of the Bismarck Reich , Munich 1983, p. 216 with additional information

- ↑ Klaus Erich Pollmann: The North German Confederation - a model for the parliamentary development capacity of the German Empire? , in: Otto Plant (Ed.): Domestic Political Problems of the Bismarck Reich , Munich 1983, p. 222.

- ^ Gerhard Lehmbruch : The Unitarian Federal State in Germany: Path dependency and change. Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne 2002, p. 38.