Cesare Battisti

Cesare Battisti (born February 4, 1875 in Trento , then Austria-Hungary ; † July 12, 1916 there ) was a geographer and a socialist member of the Austrian Reichsrat and the Tyrolean state parliament . As an irredentist , Battisti joined Italy in the war against Austria at the beginning of the war in 1915 . In 1916 he was captured by Austrian state riflemen and, after a short trial, executed in Trento for high treason . Since then, different interpretations of the nationality conflict have been attached to his person in Austria and Italy .

Life

Youth and Political Socialization

Battisti was born as the son of a businessman in Trento, then Austria . After attending grammar school in Trento , he studied geography at the University of Vienna , but moved to the University of Florence in 1896 , where he successfully completed his studies.

During his time as a student in Vienna, Battisti experienced his first political socialization in socialist circles around Wilhelm Ellenbogen and began to be active as a journalist. In Florence he made the acquaintance of the socialist intellectual Gaetano Salvemini , in whose environment he also met his future wife Ernesta Bittanti, whom he married in 1899.

At the turn of the century Battisti was actively involved in building up the socialist party in Trentino , including as editor of the magazine L'Avvenire . In 1911 he was elected to the House of Representatives of the Austrian Reichsrat for the Socialists ; In 1914 he also received a mandate for the Tyrolean state parliament .

In the course of the growing nationality conflict within the multi-ethnic state Austria-Hungary , Battisti turned away from socialist internationalism and joined the Italian irredentists . The destruction of the Italian law faculty at the University of Innsbruck in 1904 ( Fatti di Innsbruck ) is considered a key event in this regard, which Battisti confirmed that the social situation in Trentino could only be improved by breaking away from Austria and joining Italy.

War volunteer against Austria on the side of Italy

Battisti left for Italy on August 12, 1914, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, with a passport that had been issued shortly before by the head of the Police Commissioner in Trento, Government Councilor Wildauer, against his promise to return to Austria-Hungary . There he actively campaigned for the Entente to enter the war in order to detach the Trentino from Austria-Hungary and connect it to Italy. In contrast to Ettore Tolomei and Gabriele d'Annunzio , Battisti did not demand the strategically important Brenner Pass as the northern state border of Italy, but rather a demarcation along the linguistic-cultural dividing line between German and Italian cultural area at the Salurner Klause , a demand that arose in 1919 did not enforce the peace negotiations of Saint-Germain and led to the Italian annexation of Trentino and South Tyrol (south of the Brenner).

When Italy entered the war in May 1915, Battisti volunteered for the Italian army . He first served as a simple soldier in the Alpini - Battalion "Edolo"; in a skier unit he fought, among other things, on the Adamello . Battisti received several awards and was soon promoted to lieutenant . After a transfer to the "Vicenza Battalion" he fought on Monte Baldo and in 1916 in the South Tyrol offensive on Monte Corno (now Monte Corno Battisti ), a side summit of Monte Pasubio . There he was captured by Austrian troops on July 10, 1916 during a repeated Italian attack attempt, together with the irredentist Fabio Filzi . In contrast to Filzi, who gave a false name when captured and was finally identified by the ensign of the regional riflemen Bruno Franceschini from Trentino, Battisti immediately identified himself as such.

Court martial and execution

After identification, Battisti and Filzi were brought to Trento on July 11th. Battisti was driven through the city on an open cart , his hands clasped in chains, and mocked and spat at by residents loyal to the state. The following day, 12 July 1916 Battisti and Filzi in were Buonconsiglio from the court of the Austro-Hungarian military base commands in Trent because of high treason to death by the strand condemned the trial against Battisti took only two hours. In contrast to Filzi, who was sentenced under military criminal law as a deserter of the Austro-Hungarian army, Battisti was sentenced under civil criminal law. The execution by the Viennese executioner Josef Lang took place immediately after the conviction in the northern moat of the Castello del Buonconsiglio on the choking algae . At the site of the execution of Battistis, Filzis and Damiano Chiesa , who was executed in May 1916, in the Fossa dei Martiri (German: "Trench of the Martyrs"), memorial stones commemorate these events.

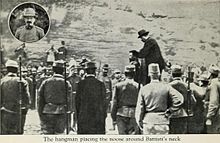

The circumstances of the Battisti trial and his execution caused a stir both domestically and abroad due to a number of special incidents. Battisti had to reckon with his conviction due to the fact of high treason , but he was further degraded by the Austrian authorities. Battisti was accused of “long-standing treacherous attitudes” and “undignified affiliation with an enemy who was also contemptible from a moral point of view”. Furthermore, it was declared that as the ringleader and the “cause of Italy's bandit attack on the monarchy”, he was responsible for the “rivers of innocent blood of our braves against the Welsh hereditary enemy”. Battisti's request, as officers honorably shot to be and to wear the Italian officer's uniform during his execution was rejected by the authorities. During the execution, the cord used by the executioner Lang broke, so that Battisti had to put a new rope around his neck. Following Battisti's execution, Lang and numerous onlookers posed for a photo, which was then widely circulated as a postcard.

The bodies of the executed Battisti and Filzi were buried shortly after the execution in the grounds of the Castello del Buonconsiglio. On October 31, 1918 - shortly before the Italian troops marched into Trento - they were reburied in a mass grave by the Austrian military, where he was finally exhumed in November by the Italian military who had moved in. After the body of Battisti's son was identified, it was ceremonially laid out in Trento. In 1935, Battisti's remains were buried in a monumental mausoleum near Trento built by Italian fascists . The bones of Fabio Filzi and Damiano Chiesa are now in the Castel Dante ossuary in Rovereto.

reception

Cesare Battisti's fate was dealt with intensely and controversially in nationalist and anti-nationalist discourses shortly after his death.

Nationalist interpretations: In Austrian circles loyal to the emperor and German nationalists , Battisti was considered the epitome of the Italian traitor at the latest after his execution. In Italy, however, as a later representative of the Risorgimento, he was posthumously awarded the highest military order and, like other irredentists ( Fabio Filzi , Nazario Sauro , Guglielmo Oberdan ) styled a national hero, after whom numerous public institutions were named. Battisti is also mentioned in the fourth stanza of the patriotic hymn La leggenda del Piave .

In his home region of Trentino , Battisti was accepted into the Accademia Roveretana degli Agiati as an honorary member in 1920 with other Protomartiri della Grande Guerra . The mountain on which he was captured by the Austrians was given the addition Battisti to the original name Monte Corno .

Although a socialist , Battisti was also captured by the Italian fascists against his wife's will , who built a mausoleum for him in his hometown of Trento in 1935 . A bust of Battisti designed by Adolfo Wildt can also be found in the interior of the victory monument in Bolzano, which was inaugurated in 1928 and which was originally intended to bear Battisti's name. Only the public resistance of Battisti's widow Ernesta Bittanti resulted in the monument not being named and instead being dedicated by Mussolini to the Italian victory in World War I. Nevertheless, the monument architect Marcello Piacentini reserved the entire northern niche of the Battisti monument and flanked its bust with quotations from the Twelve Tables law and from Titus Livius .

Anti-nationalist interpretations: Although the national-contradicting interpretations of the figure of Battisti determined the public discourse for a long time, historical interpretations also existed from the beginning that emphasized the failure of nationalisms in the figure of Battisti. The Austrian writer Karl Kraus addressed Battisti's execution and, in particular, the display of his corpse for photography immediately after the events in his work The Last Days of Mankind . Kraus did not focus on Battisti's death, but on the self-destructive work of Austrian chauvinism :

“ The complainer: The Austrian face is any face. It lurks behind the switch of the life path. It smiles and grins depending on the weather. (...) But especially since it is the hangman's. The Viennese executioner, who on a postcard showing the dead Battisti, holds his paws over the head of the executed man, a triumphant oil idol of satisfied cosiness called "Mir-san-mir". Grinning faces of civilians and those whose last possession is honor crowd close to the corpse so that they all get on the postcard.

The optimist: how? Is there such a postcard?

Nagger : It was made by the authorities, it was distributed at the scene of the crime, in the hinterland they showed "confidants" and intimate people, and today it is displayed as a group picture of Imperial and Royal humanity in the shop windows of all hostile cities, a memorial to the gallows humor of our executioners to the scalp of Austrian culture. It was perhaps the first time since the creation of the world that the devil ugh! called. "

In the 1960s, the historian Claus Gatterer linked Austria with Cesare Battisti in his book Under His Gallows. Portrait of a “traitor” to Karl Kraus' critical interpretation. Gatterer researched the political circumstances of the time and the resulting motives of Battisti, where he emphasized Battisti's fundamental democratic convictions for the first time in Austria:

“This book is dedicated to a non-nationalist irredentist , an ' internationalist ' and pacifist socialist who in 1914, after others had started the war, became both the standard bearer of the 'last Risorgimento War' and the destruction of the plurinational Habsburg monarchy. Battisti chose the path that other non- or anti-nationalists had taken. I just want to mention one: the first President of Czechoslovakia , Tomáš G. Masaryk . The two, Battisti and Masaryk, pursued a similar, if not the same goal: Battisti saw the smashing of Austria as an opportunity to make Giuseppe Mazzini's dream come true: the creation of the united (national) states of Europe ; less ambitious, on the other hand, Masaryk, for whom the war (by completing the process of disintegration of Austria) should result in the formation of a new democratic community and unity of the Danube peoples. "

In Italy and in Trentino, Cesare Battisti's democratic sentiment was primarily carried on by his widow Ernesta Bittanti and their son Gigino Battisti (who exposed themselves as anti-fascists in the 1930s and 1940s ). In the 1970s and 80s, a critical Trentino and Tyrolean regional historiography followed on from its reception history and from Claus Gatterer's approaches.

photos

The capture of Battisti and Filzi on Monte Corno in a picture by the war painter Hans Bertle ( Tyrolean State Museum )

Bust of Battisti in Verona

Battistis Mausoleum in Trento

Memorial plaque in Rome

Battisti in the Victory Monument of Bolzano

literature

- Non-fiction

- Gaetano Arfè: Battisti, Giuseppe Cesare. In: Alberto M. Ghisalberti (Ed.): Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani (DBI). Volume 7: Bartolucci – Bellotto. Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana, Rome 1965, with extensive information on his publications.

- Battisti Cesare. In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 1, Publishing House of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, Vienna 1957, p. 53 f. (Direct links on p. 53 , p. 54 ).

- Claus Gatterer : Under his gallows stood Austria - Cesare Battisti. Portrait of a “traitor”. Europa-Verlag , Vienna a. a. 1967.

- Hans Hautmann : Military Trials against Members of the Austrian Parliament in the First World War , in: Mitteilungen der Alfred-Klahr-Gesellschaft (Vienna), No. 2/2014, pp. 1–11.

- Vincenzo Cali: "No man's land". Cesare Battisti, Trentino and the Frontier Discussion 1914/15 . In: Johannes Hürter , Gian Enrico Rusconi (ed.): Italy's entry into the war in May 1915 . Oldenbourg 2007, plus special issue of the quarterly issue for contemporary history . ISBN 978-3-486-58278-9 , pp. 101-116.

- Mario Isnenghi among others: Identity conflicts and memory constructions. The “Martyrs of Trentino” before, during and after the First World War: Cesare Battisti, Fabio Filzi and Damiano Chiesa (studies of Italian literature and culture in the 20th and 21st centuries 2). Berlin-Münster: Lit-Verlag 2018. ISBN 978-3-643-13896-5

- Fiction

- Karl Kraus : The last days of mankind . Tragedy in five acts with prelude and epilogue. The torch , Vienna 1919.

- Franz Tumler : A note from Trento. Suhrkamp , Frankfurt 1965.

Documentaries

- Clemente Volpini, Graziano Conversano: Cesare Battisti. L'ultima fotografia . RAIstoria 2014, 60 min. (Online video)

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Battisti trial file of July 12, 1916 file number 1796 / 16–1 in the original and in the Italian translation, published in 1935 (PDF; 88 MB), accessed on October 27, 2017

- ↑ Alexander Jordan : War for the Alps: The First World War in the Alpine Space and the Bavarian Border Guard in Tyrol. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2008 ISBN 978-3-428-12843-3 p. 147

- ^ Hugo Hantsch: Leopold Graf Berchtold. Grand master and statesman . Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1963. Volume 2: p. 696 and István Diószegi: Foreign Minister Stephan Graf Burián. Biography and diary section . In: Annales Universitatis Scientiarum Budapestinensis de Rolando Eötvös nominatae. Sectio historica 8 (1966), pp. 169–208, here: p. 177

- ↑ Hans Hautmann: Military Trials against Members of the Austrian Parliament in the First World War , in: Mitteilungen der Alfred Klahr Gesellschaft, Vol. 21, 2/2014, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Hans Hautmann: Military Trials against Members of the Austrian Parliament in the First World War , in: Mitteilungen der Alfred Klahr Gesellschaft, Vol. 21, 2/2014, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Hans Hautmann: Military Trials against Members of the Austrian Parliament in the First World War , in: Mitteilungen der Alfred Klahr Gesellschaft, Vol. 21, 2/2014, p. 7.

- ↑ Hans Hautmann: Military Trials against Members of the Austrian Parliament in the First World War , in: Mitteilungen der Alfred Klahr Gesellschaft, Vol. 21, 2/2014, p. 9.

- ↑ Hans Hautmann: Military Trials against Members of the Austrian Parliament in the First World War , in: Mitteilungen der Alfred Klahr Gesellschaft, Vol. 21, 2/2014, p. 9.

- ↑ Membership database of the academy

- ↑ Thomas Pardatscher: The victory monument in Bozen: origin, symbolism, reception. Athesia , Bozen 2002

- ↑ Marilena Pinzger: Stone symbol of the empire. Fascist monument architecture in South Tyrol using the example of the victory monument in Bolzano. University of Vienna , diploma thesis 2011

- ↑ Sabrina Michielli, Hannes Obermair (Red.): BZ '18 –'45: one monument, one city, two dictatorships. Accompanying volume for the documentation exhibition in the Bolzano Victory Monument . Folio Verlag, Vienna-Bozen 2016, ISBN 978-3-85256-713-6 , p. 110–113 (with ill.) .

- ↑ Karl Kraus: The last days of mankind (online edition)

- ↑ Claus Gatterer: Austria stood under its gallows. Cesare Battisti - Portrait of a "High Traitor". [Extended new edition], Folio-Verlag, Vienna-Bozen 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Article by Mimma Battisti (Cesare Battisti's granddaughter) in memory of the anti-fascist Gianantonio Manci . salto.bz , April 29, 2015

Web links

- Literature by and about Cesare Battisti in the catalog of the German National Library

- Commemoration on Monte Corno Battisto July 13, 2008

- Historical pictures by Cesare Battisti

- Cesare Battisti in my-italy

- Battisti_Reloaded. Series of events organized by the city of Bozen on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of 1916–2016

- Oliver Das Gupta: Cesare Battisti: Hero and High Traitor. In: sueddeutsche.de . July 12, 2017. Retrieved July 15, 2017 .

- Cesare Battisti and the Trentino (Feb. 4, 1875-July 12, 1916); a sketch of his life, character and ideals, by Giovanni Lorenzoni, Italian Bureau of Public Information in New York 1919

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Battisti, Cesare |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Austrian MP, officer in the Italian army and irredentist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 4, 1875 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Trento , Austria-Hungary |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 12, 1916 |

| Place of death | Trento , Austria-Hungary |