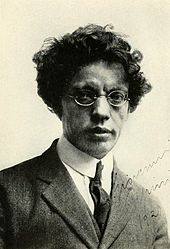

Giovanni Papini

Giovanni Papini (born January 9, 1881 in Florence , † July 8, 1956 there ) was an Italian writer . While his early work is turned towards pragmatism and futurism , a deep Catholic faith finds expression in his later work .

Life

The first publication Philosophen-Twilight , published in 1905, testifies to the critical upbringing of the autodidact Papini. In 1903 he founded the literary magazine Leonardo . In 1906 Il Tragico quotidiano was published , his first book. In the article Il crepuscolo dei filosofi in the same year, he distanced himself from the established philosophy. He varied the ideas of William James . With Giovanni Vailati and Giuseppe Prezzolini , he represented pragmatism in Italy. It stood out from the former by emphasizing the spiritual rather than the logical. His autobiographical novel Un uomo finito from 1912 also takes up his search for a philosophy of action. His second magazine, Lacerba 1913, was dominated by futurism . Papini was also involved in the magazine La Voce .

In 1908 he turned against the subordination of religion to philosophy with his article La religion sta da sè . In Ecce homo (1912) he speaks out against the possibility of a symbolic interpretation of the Gospels. In 1913, with Puzzo di cristianucci and Esistono cattolico , he denounced the contradictions of the Catholic Church. In the articles from 1908 to 1914 he still takes an anti-religious position. From 1921, religious writing dominated Papini's work. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, Papini returned to the Roman Catholic faith in which he was raised that year. ("In 1921 Papini was reconverted to the Roman Catholicism in which he had been reared".) In The Life of the Lord ( Storia di Cristo ) 1921 he tells the early life of Jesus . His religiosity is expressed in lyrical form in Pane e vino from 1926.

Papini married in 1907. On October 1, 1914, in Lacerba , he described the war as a necessary massacre , which is why one must love war. During the First World War he wanted to fight for the Entente , but was turned away due to his physical condition. The living Dante ( Dante vivo ) received the Premio di Firenze in 1933 with the blessing of Benito Mussolini , whose brother Arnaldo was originally to be awarded the prize. In 1935 he got a professorship for Italian language and literature at the University of Bologna . His Storia della letteratura italiana , published in Florence in 1937 , he dedicated to Mussolini with the words "To the Duce, the friend of poetry and poets". In 1942 Papini became vice president of the European Writers' Association founded in Weimar at the instigation of Joseph Goebbels . At the end of the war in 1945, Papini was largely intellectually and artistically discredited.

In his book Il libro nero from 1952, Papini reports a self-critical “artistic testament” by Pablo Picasso , supposedly the fruit of an interview with the painter. The text was often considered to be authentic and provided arguments against modern art , including quoting it in detail from Ephraim Kishon's book “Picasso's sweet revenge”. According to another reading, it is only a machination of Western intelligence services in the Cold War , the pro-Soviet ones Discrediting Picasso.

Works

- Un uomo finito (1912, A finished man. 1962)

- Storia di Cristo (1921, Life of Jesus. 1935)

- Pane e vino (1926, poems)

- Gog. (1929, in German 1931)

- Sant 'Agostino (1929, St. Augustine. 1930)

- Dante vivo (1933, Dante. An Eternal Life , 1936)

- Storia della letteratura Italiana (1937, Eternal Italy - The great ones in the realm of his poetry. 1940. Translated by Katharina Hasslinger)

- Italia mia (1939)

- Mostra personale (1941, from my workshop. 1944)

- Imitazione del padre (1942, rebirth and renewal. 1950)

- Saggi sul Rinascimento (1942, The essence of the Renaissance. 1946)

- Cielo e terra (1943, heaven and earth. 1947)

- Santi e poeti (1947)

- Lettere agli uomini del papa Celestino VI (1947, Cölestin VI. Letters to the People , 1948)

- Passato remoto (1948)

- Vita di Michelangiolo nella vita del suo tempo (1949, 1951, Michelangelo and his circle of life. 1952)

- Le pazzie del poeta (1950, fools, 1953)

- Il libro nero (1952, The Black Book. 1952)

- Il diavolo (1953, The Devil. 1954)

- Concerto fantastico. (1954, short stories)

- Il bel viaggio (1954, with Enzo Palmieri)

- La spia del mondo (1955, peephole to the world. 1957)

- L'aurora della letteratura italiana (1956)

- La felicità dell'infelice (1956)

- A finished person , Munich: Allgemeine Verlagsanstalt, 1925

Published posthumously

- Il giudizio universale (1957, Last Judgment. 1959)

- La seconda nascita (1958, The second birth. 1960)

- The mirror on the run. Frankfurt am Main: Gutenberg Book Guild, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7632-5819-2 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Giovanni Papini in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Giovanni Papini in the German Digital Library

- "Papini, Giovanni." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006. Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service. 9 July 2006 [2]

- More detailed short biography (English) ( Memento of January 5, 2015 Internet Archive ).

swell

- ^ A b William P. Giuliano: Spiritual Evolution of Giovanni Papini . In: Italica , Vol. 23, No. 4, 1946, pp. 304-311.

- ^ M. de Filippis: Giovanni Papini . In: The Modern Language Journal , Vol. 28, No. 4, 1944, pp. 352-364.

- ↑ Frank-Rutger Hausmann : Dense, poet, don't meet! - The European Writers' Association in Weimar 1941-1948 , 2004, ISBN 3-465-03295-0 , p. 210.

- ↑ Langen / Müller, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-7844-2453-8 , p. 30.

- ↑ See e.g. B. here [1]

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Papini, Giovanni |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian writer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | January 9, 1881 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Florence |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 8, 1956 |

| Place of death | Florence |