Railway attendant Thiel

Bahnwärter Thiel is a novelistic study by Gerhart Hauptmann . The story , written in 1887, was published in 1888. It is one of the most important works of naturalism . Hauptmann works with his main character Thiel "the helplessness against the social class society and the threat of industrialization ".

The material goes back to an accident on the railway line from Erkner to Fürstenwalde and is based on the experiences of the poet during his life on the outskirts of Berlin.

content

The action takes place in the area around Schönschornstein, the settlement area of the Gerhart-Hauptmann-Stadt Erkner . The church of Neu Zittau is mentioned in the first sentence .

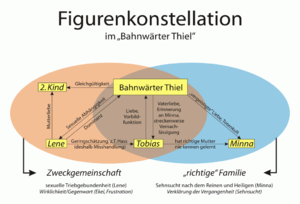

Bahnwärter Thiel is a pious and conscientious man who has been reliably performing his duties for ten years and who goes to church every Sunday. A year after the death of his first wife Minna in childbed, he married a burly maid named Lene so that he would have someone to look after his child during his working hours. Together they have a second child, because of which Lene Thiel's first son Tobias is neglected and abused. Thiel, who is deeply devoted to his late wife Minna, is more and more taken over by his second wife, who is the new head of the family. Thiel discovers that Lene is mistreating Tobias, but he does nothing to protect his son from his second wife, on whom he is now totally dependent. Still, he tries to be a good, caring father to Tobias by spending a lot of time with his son and loving him.

The tense situation changes Thiel, however, and turns him into a distraught man who increasingly takes refuge in visions in which his deceased wife plays the main role. Thiel is also tormented by remorse because, despite the promise made to his wife Minna to do everything for Tobias, he allows the child to be mistreated by Lene.

In his lonely guard house in the forest on the Berlin – Frankfurt (Oder) railway line , he increasingly loses himself in nocturnal adoration of his Minna, which gradually takes on pathological features. In one of these visions a picture of his dead wife appears to him, who is walking across the embankment and turns away from him, carrying something wrapped in cloths with her. His soul is full of shame about the humiliating tolerance of his present life. After the end of duty he can hardly wait to get home, and apparently the tormenting images of the sight of his red-cheeked son have disappeared again.

Thiel is given a piece of field at the stationer's house. Lene decides to dig up the field for Thiel's next day shift and to plant potatoes there. The penetration of his second wife into an area that has to do with his job, and which belonged to him up to now, is not right for Thiel. However, since his son Tobias is happy about the upcoming trip to his father's workplace, Thiel does not raise any objection to his wife's plans. This ultimately leads to the implementation of their will. The family goes out together. First, Thiel goes for a walk with his son, although Lene is against it because someone has to take care of the second child. Tobias can't stop being amazed and is amazed at the work his father is doing. Dreams awaken in him of later becoming a railway master . In the afternoon, Thiel goes to work while Lene puts the potatoes. When he warned him to supervise Tobias, she only shrugged.

An express train has been reported, rushes towards it, but suddenly gives emergency signals and brakes. Thiel is dismayed and runs to the scene of the accident. Tobias was hit by the train. Although still breathing, the boy with broken limbs is placed on a stretcher and taken to the next ward. Thiel goes back to his work as if stunned. He has visions again, stumbles along the tracks and talks to his invisible wife, promising her to take revenge. The backward baby answers screaming. Thiel begins to choke him in a mad rage, but the signal bell pulls him out of his madness. A train that transports workers brings the dead Tobias back, followed by the weeping Lene. Thiel collapses unconscious, is carried home by two workers and laid in his bed. Lene takes care of her husband with great sacrifice. Worried but exhausted, she too falls asleep. A few hours later, the workers bring Tobias' body home from the scene of the accident. They discover the woman slain and the infant with her throat cut. Thiel murdered both of them. The station attendant is later found sitting on the track where his son was run over. He holds his hat in his hands. After unsuccessful persuasion, several men have to forcibly remove Thiel, who is stroking his deceased son's hat all the time, from the tracks. He was first taken to a remand prison in Berlin and finally on the same day to the insane ward of the Charité . With him he wears his deceased son's cap, which he lost at the scene of the accident, and guards it like the apple of his eye.

Protagonists

Railway attendant Thiel

Thiel's robust appearance ("Herculean figure") contrasts with his sensitive interior, for which his spiritualized love for his first wife Minna, whose death deeply affected him, can be cited. Parallel to the real, everyday relationship with his second wife Lene, Thiel remembers the deceased Minna with cult-like behavior in his guard's house on the railway embankment, which becomes "a chapel" for him: "A faded photograph of the deceased opened on the table, hymn book and Bible , he read and sang alternately [...] and got into an ecstasy that increased to faces in which he saw the dead person in front of him. “Thiel feels deeply attached to his son Tobias. The child also represents the link to his beloved wife Minna. The fact that he is unable to protect Tobias from Lene's violent attacks puts a lot of strain on him.

Thiel's relationship with his second wife Lene is completely different. He's with her primarily for financial reasons and because he needs someone to look after Tobias. This community of convenience is also largely limited to the sexual level. During his marriage to Minna, Thiel was reluctant to go to work, after marrying Lene he likes to retreat to his guard house so that he doesn't have to spend time with Lene. The guard's house is his personal retreat, here he surrenders to memory and "spiritualized love" for Minna. He fears that Lene could infiltrate this almost sacred sphere. Thiel's situation is all the more difficult as he is psychologically dependent on his dream images of the deceased Minna and physically and sexually dependent on Lene, on whose work in the household and looking after the children he is dependent.

Thiel, who due to his passivity is not able to take his fate into his own hands and bring about a change that everyone can live with, steers from the beginning towards Lene and her child, which is his too, to do something. The further the storyline progresses, the more Thiel withdraws from reality, his visions increase, a tendency towards madness (progression of a mental illness) can be recognized. Thiel is often “unconscious” at the mercy of his delusions, in the end he no longer succeeds in mastering them: “He tried to bring order to his thoughts, in vain! It was an unstoppable streak and wake. He caught himself on the most nonsensical ideas and shuddered together, conscious of his powerlessness. “Thiel's social determinacy is representative of the people of his time and social class; it is the product of milieu and heredity . Thiel is also a classic antihero , not a sovereign actor, but is influenced and directed by external circumstances (Minna's death, social compulsion to remarry, need to connect to Lene in order to be able to look after Tobias) → reference to the social question in 19th century Germany Century. Thiel is a prisoner of his limited order and dependent on his profession.

Minna

Minna is Thiel's first wife who died shortly after Tobias was born after two years of marriage. Her appearance was in stark contrast to her husband's sturdy build. She was slender, pale-skinned and always looked a little sickly. Although she is no longer there, she determines Thiel's thoughts and dreams and is closer to him than his second wife Lene could ever be. The railroad attendant feels strongly connected with Minna, whom he is increasingly idealizing , and cultivates this spiritual and almost religious love, which is in complete contrast to the physical desire that Lene triggers in him.

The naming Minna is probably related to the Middle High German word Minne (love).

Lene

Thiel's second wife Lene, a former cow girl from Alte-Grund, was primarily supposed to be a surrogate mother for Tobias. Physically she is the pure opposite of the petite Minna, with a full figure and looking coarse. In terms of stature, she fits Thiel, who is also of a stocky stature and looks very robust. She is an “indestructible worker” and “exemplary housekeeper” and thus a typical representative of the lower class of the proletariat. Lene is described as domineering, primitive, gossiping, quarrelsome, tyrannical and later as brutal, also physically violent. In linguistic images it is compared with a machine or the train (see below).

From the beginning she doesn't like little Tobias. An aversion that intensifies when Lene herself has a son from Thiel, whose name is not mentioned. She prefers her own child to Tobias in everything and does not hesitate to verbally and physically abuse Tobias. This is possible because she is the dominant in the relationship with Thiel. Thiel doesn't dare to stop Lene from abusing his firstborn son. Other inhabitants of the small village call her disparagingly “the man” (despicable for woman) or “the animal”. Ultimately, she does not adequately fulfill her duty of supervision towards Tobias, whom she has always neglected anyway, which leads to Tobias walking onto the railroad tracks and being hit by the train.

Tobias

Tobias is Thiel's first child from his marriage to Minna. Outwardly he resembles his mother, is pale like her, and appears sickly and weak. At the same time it is playful, collects flowers, makes faces. The boy particularly seeks closeness and love to his father, which leads to his stepmother reacting with hatred and jealousy and subsequently abusing the child again and again. Lene also demands from Tobias that he should supervise his stepbrother, and gets angry if he does not do this job as requested by her.

Tobias admires his father and expresses his joy of wanting to become a railway master, which would mean a social advancement. The child is not aware that for the father it also serves as a link between him and his dead mother. Tobias is hit by a train and dies of the consequences, whether this happened due to intentional or negligent inattention on the part of Lene remains in the dark.

symbolism

The central thing symbol in "Bahnwärter Thiel" is the railway . In the 19th century it was a widely visible sign of the dawning machine age , which was sometimes perceived as threatening, also with regard to the social problems that industrialization created , especially in the working class. Physical and social threats from the "power of machines" to which people are subjected in their rhythm of life are clearly expressed in the railway symbolism of the novella:

Thiel experiences the destructive power of the railroad several times: The silent devotion to Minna is interrupted by "passing train trains" he himself is injured by a bottle thrown from a train, a roebuck is rammed and finally the train accident not only leads to the death of Tobias , but also cost Lene and Thiel's second son their lives.

Like a train that cannot leave its tracks, Thiel's life is also “on rails” due to its psycho-social determination . Since he cannot break his dependency on Lene and his social class, nor does he try to, he is controlled by others and his life is steered on a fixed path. Like a train, the action "races" towards the abyss, as Thiel only reacts passively in view of the dubious developments (abuse of the son, increasing dependence on Lene, increased flight into the dream world).

The features depicted in the novella are not portrayed as a force created and controlled by man, but as a continuation of the demonic power of nature: “Two red, round lights penetrated the darkness. A bloody glow preceded them, turning the raindrops in his area into drops of blood. It was like a rain of blood falling from the sky. Thiel felt a horror and, the closer the train came, the greater fear. "

The railway symbolism is supported by thematically based linguistic images: “Thiel was able to get up and do his job. True, his feet were heavy as lead, although the track circled around him like the spoke of an immense wheel, the axis of which was his head; but at least he gained strength to hold himself upright for a while. "

Finally, the railway symbolism is also transferred to Lene: Lene, who for Thiel has an “indomitable, inescapable” power that puts a “web of iron” around him, also works with the “endurance of a machine. In certain intervals she straightened up and took deep breaths [...] with a panting, sweat-dripping chest. "Like the regular trains that shoot out" milk-white steam jets ", Lene now penetrates Thiel's quiet place of worship at the station guard's house and brings it to the end the train and Lene's inattention Tobias death.

The fact that Thiel has to cross the Spree every day on the way to his work stands for the seclusion in which the Thiel family lives. This makes it clear that he keeps his family and work life strictly separate from each other. As soon as Thiel gets the field at the station guard's house from the railway master and Lene wants to cultivate it, a break occurs that makes Thiel nervous.

With the figure Thiel, Hauptmann shows his view of the determined human being, driven by the powers of the psyche and sensuality.

Classification in naturalism

Naturalistic features in the railway attendant Thiel

The main character of the story is an antihero whose everyday working life (social issue in the 19th century) is portrayed. Thiel is a main character trapped in her milieu, whose life is determined by it. The aim of the amendment is to denounce the misery of the workers and to draw the attention of bourgeois circles to it. The narration is characterized by a very precise and detailed description of the event, with precise information on the place and time, such as "Schön-Schornstein, Neu Zittau ". Except for the dream sequences, the narration is chronological. Seconds style flows into the action again and again (example from train guard Thiel in the article there).

Man is a product of milieu and inheritance, signals the image of man. Instinctiveness is a dominant feature in the narrative. The everyday, the lowly, the ugly are depicted, the misery is consciously emphasized.

Anti-naturalistic characteristics in the railway attendant Thiel

Anti-naturalistic features are for example the strong color metaphors (especially red, black), many images of nature, metaphors, comparisons, symbols (including romantic elements), hardly any colloquial language, no dialect and little literal speech.

The sympathy for the characters is directed, Thiel's character is designed with psychological depths. At the beginning of the amendment there is a shortening of ten years. Predictions are made, for example with regard to dreams, whereby these are linked with mystical features and a fusion of reality and delusion.

The characters also refer back to older literature, such as the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm (motif of the wicked stepmother), the title characters from Georg Büchner's play fragment Woyzeck (increasingly disturbed protagonist becomes violent), which was first published in a revised form in 1879, and the Narration Lenz by the same author.

Bahnwärter Thiel as a "novelistic study"

With the term study, the subtitle chosen by Hauptmann indicates the type of observation and creates the impression that there is a real, true story (or its report / study) in the novella. Similar to a scientific study, the narrator describes the event almost without comment, but the novella remains committed to authorial narration . The choice of subject (the maddened railway attendant in his poor environment) is typical of the epoch of naturalism, even if this work by Hauptmann does not do justice to an exclusive classification in naturalism.

Novellistic features in the railway attendant Thiel

Novellistic features in the narrative are a small number of people, a small amount of text (about the size of a narrative) and a short exposition (introduction of the main characters) at the beginning of the story. Further features are:

- Use of symbols (railroad)

- Action closed in itself and running linearly

- Turning point or climax at the end

- “Unheard of occurrence” in the sense of Goethe's novella : unheard of / not yet heard = novel; Occurrence = realistic, imaginable. In the end, Thiel's double murder can be seen as such an “unheard-of incident”.

Film adaptations

The book has been filmed twice under the same title:

- 1968 by ZDF under the direction of Werner Völger , with Heinz Baumann as Thiel, Eva Kotthaus as Lene, Ursula Steiner as Minna, Hans Epskamp as pastor and Bernhard Völger as Tobias.

- 1982 from the television of the GDR under the direction of Hans-Joachim Kasprzik . This film premiered on November 21, 1982. Martin Trettau played Thiel, Walfriede Schmitt played Lene and Blanche Kommerell played Minna. Rolf Hoppe was occupied as a pastor.

Audio

- Mario Adorf reads Gerhart Hauptmann Bahnwärter Thiel. Wortstark 2004, ISBN 3-920111-21-4 .

- Achim Hübner as speaker, series: Classics on CD-ROM Reclam, Ditzingen 1997, ISBN 3-15-100026-6 .

- Johannes Steck reads: Gerhart Hauptmann, Thiel railway attendant. Audiobook Verlag, Freiburg i. Br. 2017, ISBN 3-95862-017-5 .

literature

- Marc Schweissinger: Gerhart Hauptmann: Bahnwaerter Thiel or the tragedy of speechlessness. In: Carl and Gerhart Hauptmann Jahrbuch 6, (2012), pp. 61–106.

- Rolf Füllmann: Gerhart Hauptmann: "Bahnwärter Thiel." Interpretation. In: Ders .: Introduction to the novella. Annotated bibliography and person index. WBG , Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-534-21599-7 , pp. 118-125.

- Reiner Poppe, explanations on Gerhart Hauptmann: Bahnwärter Thiel , text analysis and interpretation (vol. 270), C. Bange Verlag , Hollfeld 2012, ISBN 978-3-8044-1930-8 .

- Gerhart Hauptmann: Railway attendant Thiel. Novellistic study from the Brandenburg forest. Hamburg reading books , 179. Husum 1993, 2010, ISBN 3-87291-178-3 .

- Annemarie & Wolfgang van Rinsum: Interpretations: novels and stories. Bayerischer Schulbuchverlag, 3rd edition, Munich 1991,

ISBN 3-7627-2144-0 , pp. 83-90.

Text output online

Individual evidence

- ↑ King's explanations on "Bahnwärter Thiel" sS koenigs-erlaeuterungen.de

- ^ Bahnwärter Thiel sS inhaltsdaten.de

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Gerhart Hauptmann: Railway attendant Thiel . Novellistic study, Verlag Reclam, Ditzingen, ISBN 978-3-15-006617-1 , pp. 3, 7 ff., 17, 25, 29, 31, 35, 38.

- ↑ Hauptmann, Gerhart: Bahnwärter Thiel sS reclam.de

- ↑ A combination product: reading of the complete text, but also complete. Text and image display, numerous additional functions including printing.

- ↑ with excerpts from other interpretations: Fritz Martini : Wagnis der Sprache. Interpretations of German prose from Nietzsche to Benn. Klett, Stuttgart 1970, p. 63 f .; Roy C. Cowen: The Naturalism. Commentary on an epoch. Winkler, Munich pp. 144-146; Werner Zimmermann: German prose poems of the present. 2 vols. Neufass. Schwann, Düsseldorf 1966, 1969; here vol. 1, pp. 69-71.